Neander: |

Why do you sigh, Eudosia? |

Eudosia: |

Because there is not a university for ladies as well as for gentlemen . . . |

Neander: |

You are far from being singular in this respect. I have the pleasure of being acquainted with many ladies who think as you do. But if fathers would do justice to their daughters, brothers to their sisters, and husbands to their wives, then there would be no occasion for an university for the ladies . . . the ladies would have a rational way of spending their time at home, and would have no taste for the too common and expensive ways of murdering it, by going abroad to card-tables, balls, and plays: and then, how much better wives, mothers, and mistresses they would be, is obvious to the common sense of mankind. |

James Ferguson,

The young gentleman and lady’s astronomy, 1768

Far away on the planet Venus an insignificant crater commemorates one of those forgotten women of the seventeenth century – scientific wives. In the past, stars and comets were often named after monarchs, but now the heavens have become more democratic. A crater thirty miles wide on Venus: this small and distant feature pays tribute to Elisabetha Hevelius (1647–93), a Polish astronomer whose observational expertise was known throughout Europe at the end of the seventeenth century.

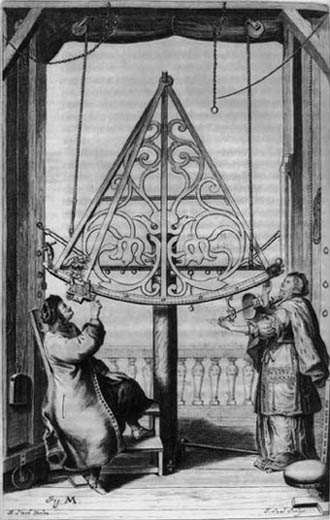

Even as a child, Catherina Koopman (her maiden name) had wanted to study the stars, and when she was sixteen she realised how to achieve her aim. Johannes Hevelius, Poland’s most famous astronomer, must have seemed very elderly to her, but his wife had recently died – the ideal opportunity for an ambitious teenager. According to the romanticised version of their courtship, she wriggled her way into his affections. Reminding him of a childhood promise he had made to teach her astronomy, she claimed to be overawed by the stars and his wisdom. Within a few months they were married, and she took on a new name and a new identity: Catherina Koopman became Elisabetha Hevelius (his first wife had also been called Catherina, but no record remains of who instigated the switch to Elisabetha). Together they observed the heavens for more than twenty years (Figure 20). ‘An old peevish gentleman’ one visitor called Johannes Hevelius. 1 Perhaps Elisabetha Hevelius also found him trying, but in compensation she could indulge her fascination with science, meet some of the world’s leading astronomical experts, and be confident that she was internationally recognised as her husband’s skilled collaborator.

After Johannes Hevelius’s death, Elisabetha Hevelius organised the publication of an important book, a giant celestial atlas that mapped 1,564 stars and included seven new constellations. He had diplomatically named one of these constellations the ‘Shield of Sobieski’ after the Polish royal family, an astute move to ensure that a common unspoken bargain came into operation: in exchange for financial support, astronomers would immortalise their patrons. Perhaps Johannes Hevelius had been following the example of Galileo, who converted the satellites of Jupiter into Medicean stars as he negotiated his career at the Medici court in Florence.

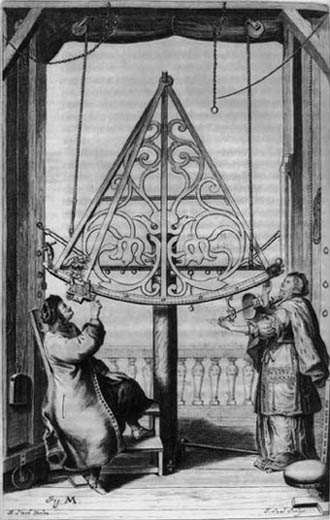

When she became a widow, Elisabetha Hevelius needed to ensure that the Polish king continued paying her a pension. She too demonstrated her skill in the patronage game. Making sure that the title of her atlas mentioned ‘the Sobieskan Firmament’, she drew up a long ingratiating preface. First came the introduction – seven lines, packed with superlatives, to salute the King – and then further on, a not-so-discreet reminder that in her husband’s heavenly map ‘glows the family shield of your Majesty marked with the victorious cross and the seven stars’. In addition, like many other scientific writers of this period, she included a symbolic frontispiece (Figure 21) to celebrate her royal patron and cement their alliance.2

Fig. 20 Elisabetha and Johannes Hevelius observing with their great sextant. Johannes Hevelius, Machina Cœlestis (Danzig, 1673).

Although Elisabetha Hevelius had organised the book’s publication, she made it clear that she was merely standing in for her dead husband. Amidst her flowery platitudes hymning the King’s military victories, she remarked that it was appropriate for her sex ‘to admire things belonging to sublime altitudes, but not to meddle with them’.3 Similarly, the allegorical frontispiece conceals Elisabetha Hevelius’s contributions by portraying a conventional view of who mattered in astronomy . . .

Fig. 21 Johannes Hevelius pays tribute to Urania and his astronomical predecessors.

Frontispiece of Johannes Hevelius, Prodromus Astronomiœ & Firmamentum Sobiescianium (Danzig, 1690).

Seated on her throne, Urania – the goddess of astronomy – is flanked by a heavenly throng of distinguished astronomers, including Copernicus, Ptolemy and Tycho Brahe. Overhead, small cherubs carry banners proclaiming the glory of God. Johannes Hevelius has apparently trudged skywards from Danzig (now Gdansk), his home town, the wealthy trading port that is lovingly depicted in the bottom right-hand corner. Bowing down before Urania, he presents her with his star catalogue, propped up on a cushion of clouds; in his right hand he clutches a real Sobieski shield, another overt reference to the constellation he had christened. Crowned with a glittering star, Urania clasps the sun and the moon as if she controlled them.

In Johannes Hevelius’s left hand, the ornate brass instrument – a miniature version of the great sextant in Figure 20 – emphasises how his reputation rested on his exceptionally keen vision and powerful apparatus. He was ‘the Prussian Lynx’, the ruler of ‘Startown (Stellæburgum), the huge astronomical observatory that he had built on the roof of his own home. To reduce the optical distortions that plagued Galileo and earlier observers, Johannes Hevelius built extremely long telescopes and devised elaborate systems of pulleys to manipulate them and stop them blowing about in the wind. Priding himself (justifiably) on these technical innovations, he refused to adopt the new telescopic sights that were invented in England; nevertheless, he achieved superb results.

More than forty years earlier, in the same year that Catherina Koopman was born, Johannes Hevelius had published a treatise on the moon whose detailed maps remained the best available for a century. This book revolutionised astronomy by including elaborate, precise diagrams of the instruments that he had invented, together with full instructions for making them. Further major books followed – a study of comets, and a two-part comprehensive study of astronomy, which included an astronomical history as well as descriptions of his observatory and his observations.

Johannes Hevelius was an innovator twice over. His large, finely crafted instruments enabled him to observe lunar craters and mountains that had never been seen before; and he insisted on sharing his expertise, so that other astronomers could replicate his results by building exact copies of his apparatus. Himself a skilled craftsman, Hevelius supervised and trained his assistants in his own workshop. He prided himself on grinding his own lenses, explaining how he picked the finest glass and designed telescope cases that were light yet durable. By the time he died, ‘the sharp-seeing Hevelius’ was celebrated all over Europe for his accurate measurements.4

Urania occupies a prominent position in Figure 21, but her female presence is iconic. There is no reference to Elisabetha Hevelius, the woman astronomer who, like her husband’s other collaborators and assistants, remains hidden behind the scenes. Johannes Hevelius pays tribute only to his famous male predecessors, the men who surround Urania and whose work (again impossible without the help of those invisible technicians) has made his own observations possible.

Johannes Hevelius hired professional iconographers to produce the allegorical frontispieces and decorations in his books, but his astronomical pictures were completely different. Unlike other astronomers, Hevelius insisted on engraving his own diagrams. He dedicated himself to making accurate images not only of the skies, but also of his instruments, his workshop and his observatory. He even employed his own printer to make sure that his instructions were closely followed. Instead of arguing with words, Hevelius relied on visual language for presenting his scientific arguments. He drew meticulous pictures that enabled his readers to share his own view of the heavens as if they were standing at his side.

Johannes Hevelius’s unprecedented concern with realism means that we can be confident in his illustrations of his rooftop observatory. Although Elisabetha Hevelius’s clothes in Figure 20 might look suspiciously glamorous, there is no doubt that she did actually use the instruments as shown. When Johannes Hevelius portrayed himself measuring stars in partnership with his wife, he was inviting their fellow astronomers to witness their daily routine – or to be more accurate, their nightly routine. Astronomical observation did, of course, take place during the hours of darkness: these pictures only appear to have been drawn during the daytime.

Adept at self-publicity Johannes Hevelius presented handsomely bound copies of his books to distinguished people all over Europe. So unlike other scientific wives, Elisabetha Hevelius’s astronomical activities were no secret because she could be seen in action. Figure 20 is one of three similar pictures, all of them unusual and powerful demonstrations of a woman’s active involvement in astronomical observation. In contrast with the allegorical frontispiece of Figure 21, the real-life Elisabetha Hevelius was no symbolic Urania, but a practising astronomer.

Only a few bare facts survive about Elisabetha Hevelius’s personal life: she was the daughter of a Danzig merchant, she bore four children, and – thanks to her husband’s devoted care – survived an attack of smallpox that left her badly scarred. For a woman, she must have been well educated, since Johannes Hevelius commented on her mathematical skills and she wrote letters in Latin, the international scholarly language.

However, Johannes Hevelius’s pictures and data records provide unique evidence of her astronomical activities. By picking Johannes Hevelius, Catherina Koopman had astutely married a distinguished citizen, a brewer wealthy enough to build his private observatory across the roofs of three adjoining houses. Within a couple of years, she was spending nights up on the roof making astronomical observations, and she became his most trusted collaborator. Visitors from all over Europe came to admire the couple’s sextant, telescope and other instruments perched up above the city near the banks of the river Vistula. Many of them met Elisabetha Hevelius, who regularly observed at her husband’s side and entertained their guests.

Because she has left no personal documents, her own feelings about her status can only be inferred. Almost certainly she felt frustrated at being denied a university education, and so had taken the best option available to her – marrying a distinguished, if elderly, astronomer. Elisabetha Hevelius must have felt torn between managing her household, caring for her three surviving daughters and passing the hours of darkness up on the roof mapping the stars. Johannes Hevelius’s first wife had taken care of the family brewery, and Elisabetha Hevelius probably had that responsibility as well. Included in the perks that came with the royal pension were a life-permit to sell beer and exoneration from paying dues to the Brewers’ Guild; scientific tourists in Gdansk can still buy bottles of Hevelius beer with his picture on the label.

Johannes Hevelius’s major instrument was the sextant shown in Figure 20, a large brass instrument used to measure the angle between two stars. Its cumbersome construction meant that two people were needed to operate it: even the handle that Hevelius holds is decorated with a miniature man and woman. Here Elisabetha Hevelius’s task is to keep her end aligned on one particular star while her husband moves the adjustable radius towards a second one; the angle separating the stars can then be read from the curved scale. Making matters more complicated, the sextant can also be tilted by the system of ropes and pulleys. Here, the two observers are making final adjustments with fine screws.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Johannes Hevelius did at least acknowledge the existence of his assistants. Although he rarely named them, he made two exceptions: his printer and Elisabetha Hevelius. He concealed his hired printer’s true identity by referring to him as Typographus, but – in contrast – he singled out Elisabetha Hevelius’s abilities. ‘My dearest wife’, as Johannes Hevelius called her in his published account of the sextant, was his diligent collaborator and a keen student of mathematics. In his opinion, he continued in an unusual declaration of equality, ‘Women are definitely just as well suited to observing as Men.’5

In 1674, eleven years after the Heveliuses’ marriage, John Flamsteed, Britain’s Astronomer Royal, received an ingratiating letter from a young Oxford undergraduate who signed himself ‘Your and Urania’s most humble Servant tho’ unknown, Edm. Halley’. Fifty years later, Edmond Halley was himself a world-famous astronomer who had inherited Flamsteed’s position, but this was their first contact. Flamsteed and other English astronomers were introducing new sighting devices, which they claimed made their telescopes more accurate. Since Johannes Hevelius was renowned for his observations, someone was needed to vet the competition and compare the rival instruments. It may well have been at Flamsteed’s instigation that Halley invited himself to Hevelius’s Startown in Danzig.

Measurements started the very night that Halley arrived, and continued for almost two months. Johannes Hevelius regarded Halley’s visit as the climax of his life’s work, his opportunity to demonstrate once and for all that his methods were the best in Europe. For this international contest between scientific technologies, he wanted to use his most reliable observers – so he chose Elisabetha Hevelius. The records show that different combinations of couples took turns working with the sextant. Sometimes Elisabetha Hevelius collaborated with Johannes Hevelius, sometimes with the printer. She also partnered Halley, presumably teaching him how to use their instruments correctly. By the time that he left, Halley was convinced that the Hevelius couple could obtain results to match the English ones for accuracy.6

Elisabetha Hevelius was responsible for welcoming visiting astronomers to Startown, and she was probably glad to meet Halley, who was only nine years younger than her. Certainly they became friendly, since she commissioned him to order some fashionable silk clothes for her in London. Figure 20 and the other illustrations suggest that she took great care with her appearance. Even if silk dresses were not the most sensible clothes for chilly night-time work on a roof at the edge of the Baltic, she was obliged to wear fine gowns for dinners. Halley does not emerge well from the transactions over this purchase. After Johannes Hevelius died, Halley got very worried about being paid. Carefully converting his expenses into the right currency, he craftily suggested that Elisabetha Hevelius should send him some of her husband’s books, a ruse that left him owing money to her.

Gossip circulated about Elisabetha Hevelius’s night-time observation sessions with Halley. Why, people wondered, had Halley lingered far longer than anticipated in Danzig, apparently too busy even to send letters back to England? Years later, Halley’s enemies were still insinuating that he had made Johannes Hevelius ‘a Cuckold, by lying with his wife when he was at Dantzick, the said Hevelius having a very pretty Woman to his Wife, who had a very great Kindness for Mr Halley and was (it seemed) observed often to be familiar with him.’7 Inevitably, historians have poured energy both into attacking and into defending her honour, scouring the sources to prove what is probably unprovable. Then as now, unconventional women posed threats to existing social hierarchies. The rumours may or may not have been true, but whether or not two people had an affair 300 years ago seems less interesting than reflecting on the ferocity of the debates. The original scandal highlights how Elisabetha Hevelius was under scrutiny as she negotiated appropriate ways to behave in a role that had few established codes. And the controversy’s endurance indicates how other women were subsequently also obliged to show that respectability could be compatible with scientific research.

Without Elisabetha Hevelius, it is extremely unlikely that her husband’s important celestial atlas would have been published. Perhaps, like Johannes Hevelius’s voluminous correspondence, the hand-written manuscripts would have been sold off by their son-in-law for a pittance. However, it is unclear exactly how much work remained to be done when he died. Elisabetha Hevelius wrote a long letter in Latin asking London’s Royal Society for help, but although her husband had been a Fellow for twenty-five years, this plea from a foreign woman was totally ignored. The Polish king was more forth-coming, and after some final tidying up, the observations and maps were printed – three books usually bound together in a single volume, the Prodromus astronomia (Forerunner of Astronomy), which included the most comprehensive and accurate star catalogue then available.

In her dedication to the king, Elisabetha Hevelius wrote that the book was the product of Hevelius’s genius. It did, however, also contain a permanent record of the many years that she had herself devoted to astronomy, although this time there were no pictures of her. Like other domestic female astronomers, Elisabetha Hevelius’s activities were now concealed from public view. She was absent from the allegorical frontispiece, and her presence disappeared inside Hevelius’s book, which presented the observations as if they were his own. Even her body vanished – after she died, she was buried inside her husband’s tomb.

The pictures of Elisabetha Hevelius in action with the sextant and other instruments on the rooftop (Figure 20) are fascinating not only because of what they reveal about her, but also because they vicariously illustrate other female astronomers who have disappeared with no such published pictures of their achievements.8

In England, Flamsteed’s wife Margaret admired the older woman whom she had never met, but whose conduct she emulated. Like Elisabetha Hevelius, she observed the skies with her husband, carried out calculations, entertained important visitors and was also left as a young astronomical widow struggling to publish her husband’s celestial atlas.9 It seems likely that other English astronomers’ wives became invisible assistants, although there are no well-documented examples of women in astronomical families before Caroline Herschel came to England towards the end of the eighteenth century.

In Germany, astronomical women were far more visible. Between 1650 and 1720, an astonishing 14 per cent of German astronomers were women, many of them collaborating at home with members of their family. When the Swedish astronomer Anders Celsius (who is now most famous for his temperature scale) travelled south to the German states in the early eighteenth century, he commented: ‘I begin to believe that it is the destiny of all the astronomers with whom I have had the honour of becoming acquainted during my journey to have learned sisters.’10

The lives of some of these women mirror Elisabetha Hevelius’s. Maria Eimmart, for instance, trained in her own father’s observatory at Nuremburg, where she studied alongside his male apprentices. A skilled artist, she specialised in producing fine, detailed drawings of the sun and the moon. To secure her astronomical career, she married the physics teacher who had been appointed to manage her father’s observatory. Her new husband was also presumably delighted with the arrangement, since when Eimmart’s father died, he automatically inherited the observatory through her.

An even closer parallel to Elisabetha Hevelius is Maria Winkelmann. She married Gottfried Kirch, an astronomer who had been trained by Johannes Hevelius. Working with her husband, Maria Kirch made original observations and taught practical astronomy to her own children. Even though she may never have met Elisabetha Hevelius, she must have known about the older woman’s expertise and active involvement in the Startown observatory.

Although there are no surviving records of comparable astronomical dynasties in England, the skilled craftsmen who made astronomical instruments similarly handed down their businesses through the generations. Women shared in the family work, and their power is made particularly evident by examining inheritance struggles – women become visible because of their legal rights. A famous example is the Adams family, who ran one of London’s most prestigious instrument concerns for almost a hundred years. When the first George Adams died in 1782, his wife Ann (her original surname is lost) took over the shop in Fleet Street until her son George Junior was fully qualified. Ann Adams was still alive when the younger George Adams died twelve years later, but within a fortnight her daughter-in-law – George Junior’s wife Hannah Marsham – had staked her own claim to the profits by trying to sidestep his brother Dudley. Dudley and his mother managed to force the wife out, but this proved to be an unwise strategy: the well-organised wife, Hannah Marsham, left a substantial estate of £20,000, whereas Dudley Adams bankrupted the family business, later becoming a shady political agitator and electrical therapist.11

In comparison with England, the guild tradition remained strong in Germany long after the mid-seventeenth century, and it seems to have fostered female participation in astronomy. Although women found it hard to gain formal recognition, they could claim an important, if secondary, role in astronomical households because making instruments was a skilled craft. Traditionally, astronomical careers were founded on training with a master inside his private observatory, not by following academic courses in a university. Women were regularly taken on as apprentices, or inherited family businesses from their husbands or fathers. They fulfilled vital functions. Like Jane Dee, they had to run the household and look after all the apprentices and hired assistants. In addition, they participated in the astronomical observations, sometimes staying up all night to record star positions and then working during the day to carry out mathematical calculations and catalogue the data.

Unsurprisingly, participation did not mean equality. In 1721, one eminent member of the Berlin Academy boasted that the high number of female astronomers in Germany put the rest of Europe to shame. Their accomplishments, he proclaimed, ‘make one recognise that there is no branch of Science in which Women are not capable’. But he was in a minority. He protested about his prejudiced colleagues who resented Maria Kirch simply because she was a woman: ‘& they would have liked to relegate her to her distaff & her spindle,’ he fumed ineffectively.12 A generation younger than Elisabetha Hevelius, and related to her via Johannes Hevelius’s assistant Gottfried Kirch, Maria Kirch illustrates how women were squeezed out of professional astronomy. Her story shows how their achievements could be masked behind the reputations of their fathers and husbands.

Like Catherina Koopman (later Elisabetha Hevelius), Maria Winkelmann (later Maria Kirch) (1670–1720) was interested in astronomy as a child. But she was realistic: university was not an option because she was a woman. Her first step was to become the assistant of a local farmer, who had stunned the elite astronomical world by reporting a new comet eight days before Johannes Hevelius found it. (Like astronomical women, this so-called ‘Peasant’ initially published anonymously.) Then Winkelmann adopted Koopman’s own strategy – marry an elderly distinguished astronomer whose first wife had died. Her family preferred a more orthodox candidate, a young Lutheran minister, but Winkelmann insisted on marrying Gottfried Kirch, Germany’s most famous astronomer.

The contrasting educational experiences of these astronomical partners were typical. As a man, he had benefited from two types of teaching: traditional training in practical astronomy at Startown in Johannes Hevelius’s workshop and observatory; and the relatively recent scholarly practice of studying mathematics at university. As a woman, Winkelmann relinquished her unofficial apprenticeship under one man to become another man’s wife and assistant. She acquired status, but she also acquired domestic responsibilities, including caring for her own children as well as those of her predecessor.

Elisabetha and Johannes Hevelius, Maria and Gottfried Kirch: these scientific couples worked as partnerships, as teams. There was no hard boundary between home and observatory, and the wife’s role merged into the husband’s. Sometimes Maria and Gottfried Kirch worked side-by-side, but divided the sky between them; that was why Maria Kirch was the first to observe the northern lights, when her husband was watching the southern half of the sky. At other times, they collaborated when two observers were needed, or else took turns so that between them they could cover the entire night.

And it was on one of those occasions, while her husband slept, that Maria Kirch spotted a comet that her husband had missed. She was the only astronomer in the whole of Germany to see it, and for the next couple of weeks they tracked its course together. So whose discovery was it – hers or his? The official scholarly language was Latin, but Maria Kirch only spoke German. Gottfried Kirch wrote the first reports in Latin, and Gottfried Kirch got the credit. It was only eight years later, in the first volume of the new journal at Leibniz’s Berlin Academy, that he opened an article with the words ‘my wife . . . beheld an unexpected comet’. Over the decade that they observed together, Maria Kirch’s observations were generally concealed behind her husband’s façade.13

Together in Berlin, Maria and Gottfried Kirch manoeuvred to get more funding for astronomy. She petitioned Leibniz for support, and he used his friendship with Princess Sophie to present her at court. ‘I don’t believe,’ Leibniz enthused, ‘that this woman could easily find an equal in the science at which she excels . . . she observes as well as the best [male] observer.’ And to placate Sophie’s doubts, he assured her not only that Maria Kirch was technically competent with instruments, but also that she was as well versed in the Bible as in the fashionable Copernican idea that the sun is stationary at the centre of our planetary system.14

But even with Leibniz as her patron, Maria Kirch could not protect her position at the Academy after her husband died. Although she had worked by his side on the Academy’s calendars for the past ten years, she lost her place as his assistant and was about to be turned out of his official home. She was desperately worried about supporting herself and her four children. Although she applied for an inferior job at the Academy, the Secretary fretted about setting a precedent by employing a woman. ‘Already during her husband’s lifetime,’ he wrote to Leibniz, ‘the Society was burdened with ridicule because its calendar was prepared by a woman. If she were now to be kept on in such a capacity, mouths would gape even wider.’15 Leibniz rallied to her support, but won only a brief reprieve: six months’ housing, about a month’s wages and a gold medal.

Maria Kirch survived by moving to a private observatory, where she rose to become a master astronomer with two students of her own to train – under the craft guild tradition, women could achieve high positions in Germany. The Hevelius family later invited her to reorganise the Startown observatory, and she stayed there for eighteen months. But academic astronomy excluded women. Even though she did eventually publish in German under her own name, Maria Kirch could only get back inside the Berlin Academy by becoming assistant to her own son Christfrid.

This pattern of discrimination was perpetuated. Like his father, Christfrid Kirch had benefited from the dual astronomical education that was unavailable to his mother: a year at university as well as practical training in observation from his parents. And so Christfrid Kirch inherited his father’s position at the Academy, the job that was denied to his mother. Maria Kirch’s daughters had received the same domestic apprenticeship as their brother, but were not eligible to go to university; echoing her experiences, they could only find paid work as Christfrid Kirch’s assistants. After he died, they were forced to observe from home, where they complained about the tiny windows and their inferior instruments.

Leibniz told Princess Sophie that Maria Kirch was ‘a most learned woman who could pass as a rarity . . . one of the best rarities in Berlin.’16 What a double-edged compliment! Was she a priceless treasure to put on display, or was she a curiosity, a freak of nature to be marvelled at? In any case, as Leibniz knew, although she might have been rare, she was not unique. Three years earlier, a German pastor called Johann Eberti had published his Open Cabinet of Learned Women, an influential set of female biographies. Trawling through all the available literature, Eberti assembled together almost 500 exceptional women from the past, sorting them by his own criteria into saints, heroines and scholars.

Like pinning out butterflies in a case, displaying rare women within a collection was not the same as granting them freedom in the real world. Eberti’s Open Cabinet provided a valuable resource for men who were keen to parade their egalitarian principles while maintaining their privileged status. One of the women preserved in print by Eberti was Maria Cunitz, who spoke seven languages, married her astronomy teacher and published a book on practical and theoretical astronomy. ‘She was so deeply engaged in astronomical speculation,’ reported Eberti, ‘that she neglected her household. The daylight hours she spent, for the most part, in bed (concerning which all manners of ridiculous events have been reported) because she had tired herself from watching the stars at night.’ Later writers trotted out Eberti’s account of Cunitz because it confirmed their opinion that being an astronomer was incompatible with a wife’s domestic duties.17 Women like Elisabetha Hevelius, Margaret Flamsteed and Maria Kirch demonstrate their error.