Is it not then more wise as well as more honourable to move contentedly in the plain path which Providence has obviously marked out to the sex, and in which custom has for the most part rationally confirmed them, than to stray awkwardly, unbecomingly, and unsuccessfully, in a forbidden road? . . . Is the author then undervaluing her own sex? – No. It is her zeal for their true interests which leads her to oppose their imaginary rights.

Hannah More, Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education, 1799

February 1828: an unusual meeting is taking place at London’s Astronomical Society. The Vice-President, James South, is discussing William Herschel, the astronomer most famous for discovering the planet Uranus. ‘Who participated in his toils?’ asks South in mock-astonishment. ‘Who braved with him the inclemency of the weather? Who shared his privations? A female – Who was she? His sister.’ Although much of his speech is about William, South is about to award a coveted gold medal to this sister, Caroline Herschel (1750–1848). (Conveniently, she is far away in Germany, so South has not had to confront the question of whether she should be invited into this male enclave to receive her prize.) Caroline Herschel has discovered eight comets and several nebulae, but South admires her for the calculations she carried out on William Herschel’s observations, for her ‘unconquerable industry’ in helping her brother.1

February 1835: seven years later, and the Royal Astronomical Society is in a quandary. Should they make Caroline Herschel an honorary member, even though she is a woman? After much debate, they vote to admit her, arguing that old-fashioned prejudice should not stand in the way of paying tribute to achievement. They formulate what is perhaps the first statement of equal opportunities in science: ‘while the tests of astronomical merit should in no case be applied to the works of a woman less severely than to those of a man, the sex of the former should no longer be an obstacle to her receiving any acknowledgement which might be held due to the latter’.2 The language may be outdated, but the sentiments are modern.

Caroline Herschel was rewarded not for her own discoveries, but because she recorded, compiled and recalculated her brother’s observations. She was ‘his amanuensis’, reported South, thus consigning her to the scientific margins. South described how, after a night’s work together at the telescope, William observing and Caroline recording, it was Caroline who spent the morning copying out the readings neatly. And it was Caroline who performed the calculations, arranged everything systematically, planned the next day’s schedule and collated their observations in publishable form.

In some ways, Caroline and William Herschel’s astronomical partnership resembles the family craft traditions in Germany a hundred years earlier. Like Elisabetha Hevelius and Maria Kirch, Caroline Herschel was acknowledged to be highly competent, but her achievements were concealed behind the name of the man in the family. Yet there were also significant differences. Most obviously perhaps, the Herschel family was known for its musical rather than its astronomical expertise; William Herschel did not undergo a normal apprenticeship and never studied at university. Just as importantly, by the end of the eighteenth century attitudes towards science as well as towards women were changing. In England, enterprising men had shown that science was useful and could also be profitable – earning enough money to support a family now seemed a viable option. Campaigners like Mary Wollstonecraft were demanding better education for girls, but even women who worked still maintained that the sexes were cut out for separate roles in life.

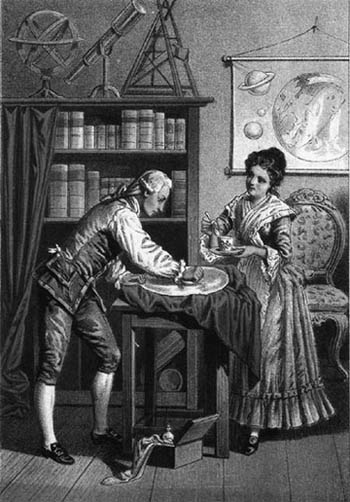

Caroline Herschel was often described as a humble assistant. Pictures like the one reproduced as Figure 22 consolidated her subservient role. It shows her meekly proffering a cup of tea to sustain William, who scarcely seems to notice her presence as he busily polishes a mirror. The scene radiates domestic harmony. Dressed in a pretty pink gown, she serves while he works. No indication here of her diminutive size and the facial scars left over from a childhood bout of smallpox. One thing jars: the open box on the floor with a miniature doll inside. Might this symbolise Caroline, peering out from the confines of her upbringing, but unable to escape? This romanticised image encapsulates the conventional story of the Herschel couple . . .

Fig. 22 Caroline and William Herschel. A. Diethe, coloured lithograph.

Originally from Germany, William was a professional musician in Bath when he brought his younger sister over from Germany to train her as an opera singer. As William’s hobby of astronomy turned into a passion, Caroline abandoned her musical career and dedicated herself to being his assistant as well as his housekeeper. William’s prowess is chronicled by the instruments arranged on the bookcase. Although they are not accurately drawn, they are meant to provide a potted history of astronomy. On the left is an armillary sphere, developed by the Greeks for observing the stars and still used for teaching in the Herschels’ time. Next to it, the small brass telescope indicates how William worked when he first became interested in the stars. On the right sits a model of his most famous instrument, a giant telescope housed in a wooden frame.

William succeeded because he was a skilful researcher who constructed instruments of extremely high technical quality. By building telescopes with an extraordinarily high magnifying power, he discovered that some stars were in fact double. In order to see further and further out into space, he needed telescopes that would gather lots of light to detect faint and distant stars. This meant building massive instruments with very large, smooth reflecting mirrors, which William ground and polished himself. Caroline later recalled that he once spent sixteen hours continuously working on a particular mirror, and this picture reflects his reputation as a skilled craftsman who sold telescopes all over the world.

At first, professional astronomers were scathing. A lunatic fit only for Bedlam, muttered conservative critics, who ridiculed this provincial upstart’s claims that he could build telescopes twenty times more powerful than existing ones. But William was vindicated in 1781, when he noticed a mysterious object in the sky. Within months, astronomers all over the world were celebrating his discovery of an eighth planet. Like Galileo and Hevelius, he solicited royal patronage by naming it after George III, even though it was soon rechristened Uranus. This was the first modern addition to the classical universe, and the poet John Keats later evoked the keen excitement:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken . . . 3

After George III invited William up to London to demonstrate his powerful telescopes, the Herschels’ life was transformed. Granted a royal pension to provide astronomical entertainment for the King and his family, William could afford to give up the music that had financed his research. Caroline and William moved across the country in order to be near the castle at Windsor, and William built larger and larger telescopes, culminating in one forty feet long with mirrors four feet in diameter.

William’s major interest lay not in the planets, but in the stars. Like a natural historian gathering specimens, he wanted to collect stars from all over space and group them into different types. He set out to make an inventory of the universe and map the dimensions of our galaxy. Through his powerful telescopes, what looked like luminous blurs in smaller instruments resolved themselves into myriad star clusters that could be distinguished from genuine cloudy nebulae. Because he had discovered and catalogued distant stars and nebulae, awards for William poured in – honorary degrees, a knighthood, the presidency of the Astronomical Society.

Recognition for Caroline came only after William’s death. By then, she was living on her own, forced by William’s marriage to move out of the home and workplace they had shared for sixteen years. Following a decision she always regretted, Caroline went back to Germany, where she dedicated herself to helping William’s substitute – his son, who became the famous Victorian astronomer, John Herschel. After a life of scientific servitude to her brother, she devotedly compiled star catalogues for her nephew.

By the time that she was fifty, Caroline Herschel had become a token scientific woman, astonishment being reserved for her sex rather than her discoveries. When King George III demanded to see her comet, one of the court attendants – the novelist Fanny Burney – interrupted her game of cards to dash out into the garden and climb up the telescope’s steps. ‘It is the first lady’s comet,’ she wrote, ‘and I was very desirous to see it.’4

Modern biographers have also seized on this ‘first’, seeking to rescue Caroline Herschel from her secondary role as a scientific helpmate and convert her into a female icon of science. Feminists have rewritten Caroline Herschel’s story to underline her independent achievements and the contributions she made towards breaking down prejudice against scientific women. But when does a shift of emphasis become an exaggeration, a distortion? Scientific women have been concealed for so long that it’s very tempting to overstate the case and convert them into unsung heroines. Retelling women’s stories to make them conform with modern ideals is historically insensitive; moreover, it is not very helpful for understanding how the past has led to the present.

A Victorian feminist interpreted their relationship rather differently. Writing in an anthropology journal, she declared that ‘the splendid renown attached to Sir W. Herschel’s name was largely due to his sister’s superior intelligence, unremitting zeal, and systematic method of arrangement’.5 Caroline Herschel’s ‘superior intelligence’ may be hard to prove, but this claim that William Herschel’s fame depended on her activities was no exaggeration. Far more than a simple helper, she was indispensable for establishing William Herschel’s reputation and compiling his work for publication. Through her collaboration with her brother, Caroline Herschel strongly affected the course of astronomy. This aspect of her achievements seems far more significant than her discoveries of a few small comets, several of which were in any case also observed by other astronomers.

When astronomers are observing the night skies, they often dictate readings to a scribe so that they can keep their eyes attuned to the dark. William Herschel ran a family-based operation. His major assistants were his sister Caroline, who converted raw data into publishable, error-free knowledge, and their brother Alexander, a musician in Bath who was probably as technically gifted as William. Beneath them in the hierarchy were the men who manipulated the heavy telescopes at night. And still lower were the fifty or so artisans, identified by numbered shirts, who carried out the unskilled manual labour. All of these invisible assistants have been concealed by William Herschel’s reputation.

Caroline Herschel’s role was exceptionally important because of the very nature of her brother’s research. Unlike previous astronomers, he concentrated on collecting and classifying large numbers of stars, so that Caroline Herschel’s cataloguing skills were of central importance. It was after her early success at logging nebulae that William Herschel decided to pursue this new line of enquiry, the one that came to dominate his research and consolidate his fame. Lacking her patience and meticulous attention to detail, he relied on Caroline Herschel’s scientific input. Joined by their brother Alexander in the summer months, they worked together as a team – although only William Herschel received the prestige.

Even sympathetic biographers are forced to recognise that Caroline Herschel colluded in her downtrodden state. ‘I am nothing, I have done nothing,’ she wrote; ‘a well-trained puppy-dog would have done as much’ – a self-abnegating remark that cannot simply be dismissed. Because Figure 22 demotes her into a tea-bearing servant, feminist campaigners would like to dismiss it as a typical chauvinistic denigration of women’s involvement in science. However, while it does serve this function, it also matches Caroline’s own description of the care she lavished on her ‘brother when polishing, since by way of keeping him alive I was constantly obliged to feed him by putting the victuals by bits in his mouth . . . serving tea and supper without interrupting the work with which he was engaged.’6

Commentators coined polite euphemisms to disguise Caroline Herschel’s slavish servility. ‘All shyness and virgin modesty,’ remarked Burney’s father when he met her, and Burney herself acutely noticed how Caroline Herschel allowed her brother to answer questions on her behalf. Humility is itself a form of greatness, judged a sanctimonious Victorian relative keen to polish up the family reputation. A 1930s biographer praised ‘her beautiful character’, even though Caroline Herschel’s autobiography reveals an embittered, prickly, solitary woman who shunned friendly advances and perceived the world as a hostile place.7 Recent writers, keen to promote female participation in science, have glossed over her emotional difficulties to focus on her achievements. Concealing her problems seems almost as insulting as minimising her ability, and also reduces the modern relevance of her experiences. Many women still lack self-confidence and allow themselves to become victims of a scientific system that is geared towards aggressive, arrogant styles of behaviour.

Caroline Herschel was evidently a woman of huge ability, who did make independent discoveries, but rewriting her life prompts important questions about how science’s own history should be told. Does it make sense to celebrate her eight comets rather than the many years she devoted to systematic research? Methodical work lies at the core of scientific progress, yet we still celebrate the unusual, the breakthrough, the single spectacular event. Caroline Herschel’s importance for her brother’s research was far greater than most of their contemporaries realised, yet she allowed her reputation to be channelled through him. How did this happen? Was it just a consequence of eighteenth-century attitudes towards women, or do her experiences have resonances in modern science? Caroline Herschel’s experiences illustrate how compromises, concessions and survival strategies can have damaging long-term effects, as a person gradually slides into a situation of no-return.

Caroline Herschel was immured in domesticity throughout her life. Like a failed Cinderella, she escaped the drudgery imposed by her mother and her family, only to become the handmaiden of her elder brother, the adored yet demanding fairy prince who whisked her off to England. Under his care, her duties expanded beyond the conventional cleaning and cooking to include menial tasks like sieving horse manure to make smooth beds for telescope mirrors. Even her independent observations relied on routine, as she systematically searched the skies for comets, an activity with an appropriately domestic label – sweeping.

As a child in Hanover, her father – an army musician – showed her the constellations and wanted her to be educated, but her mother was obdurate. Caroline, she insisted, must stay at home to cook and clean. Illiterate herself, perhaps the mother resented Caroline’s attempts to gain skills and opportunities that she herself had been denied; certainly, with six surviving children, she wanted to lighten her own workload by keeping her daughter at home. From her perspective, learning threatened the family harmony by giving her sons high ambitions that would take them away from home, and she squashed heated scientific discussions in case they woke the younger children.

Caroline seethed with resentment and daydreamed unrealistically about life as a governess. ‘I could not bear the idea of being turned into an Abigail or housemaid,’ she wrote later in a memoir that is choked with self-pity and frustration. She stored up bitter memories: being banned by her mother from dance lessons that had already been paid for, missing family reunions as she toiled in the scullery, harsh punishments for her clumsy serving at dinner parties. She soon learned to take her pleasures vicariously, eavesdropping on her brothers’ animated conversations because ‘it made me so happy to see them so happy’.8 Looking back, she singled out William for his kind behaviour. Twelve years older, he was the only one who comforted her when she returned, cold and forlorn, from an unsuccessful search for her father at a military parade.

Opting for music rather than war, William escaped from the army when Caroline was seven and found refuge in England, where he earned his living by composing, playing and teaching. But he was dissatisfied. Music, he thought, should be for pleasure, not for money. Also, he was lonely. In three years, he complained, ‘I have not met a single person whom I could feel worthy of my friendship.’ He went home briefly, the popular son who kindly complimented his little sister’s confirmation dress, before dashing back to England leaving her plunged in depression, mechanically trudging from one chore to the next. First her father died, then her only friend; her younger brother went to England, but Caroline was left behind, endlessly sewing sheets and knitting ruffles, too proud ‘for submitting to take a place as Ladiesmaid’ and scarred by her father’s advice to forget about marriage ‘as I was neither hansom or rich’.9

Eight long years went by before she was rescued. Silencing their mother’s protests by hiring a family servant, William announced that he was taking Caroline to England to train her as a singer. Torn between joy and guilt, she made enough clothes to last everyone a couple of years, and embarked on the two-week journey to Bath, where she slept in the attic with Alexander, while William occupied the handsomely furnished rooms on the first floor. William had already attained god-like proportions in Caroline’s eyes, and she spent the rest of her life revolving around him. As her nephew commented: ‘There never lived a human being in whom the idea of Self was so utterly obliterated by a devotion to a venerated object.’10 Uneducated, knowing no English, Caroline willingly submitted herself to William’s domination, binding herself deeper and deeper into a situation of voluntary exploitation.

Her days settled into arduous routine, broken only by periods of relaxation listening to William enthuse about astronomy. Work started over an early breakfast, when William taught her English, arithmetic and bookkeeping – the skills she needed to manage the household for him. Then followed her singing practice, squeezed in before her other duties. She started by tackling English cooking and the nightmare of shopping in a foreign language, but soon increased her responsibilities by sacking the servant (‘a hot-headed old Welshwoman,’ she sniffed).11 Like many lonely people, she even resented attempts to break her solitude. Friendly visitors were dismissed as idiots, and she bristled with animosity throughout a trip to London, jealously suspecting her hostess of wishing to marry William.

Caroline’s musical career flourished under her brother’s guidance. She started to be billed in solo parts, but after six years she turned down the offer of a performance in Birmingham that could have been the start of an independent life. ‘I never intended to sing anywhere but where my Brother was the Conductor,’ she declared.12 Sisterly loyalty, or self-punitive fear of freedom? Recognising her devoted commitment, William liberated himself by passing on tedious chores to her. As her days became eaten up in training the choir and copying out sheet music, she relinquished all her own ambitions.

William’s obsession with astronomy had already started to take over their lives. Over the breakfast table, he imposed ‘Little Lessons for Lina’ that included enough algebra and geometry for her to be useful in recording observations, and he kept snatching her away from singing to help him test his instruments and build new telescopes. To Caroline’s horror, a couple of summers after she arrived in Bath, William converted their home into a workshop. A carpenter took over the elegant drawing-room, a large lathe was installed in a spare bedroom and soon the garden became a construction site. William was still giving concerts and lessons, even though his pupils were disconcerted by the globes and telescopes piled up on the piano.

Caroline was not just a passive helper. Down in the basement, while a furnace melted the metals to cast enormous mirrors, Caroline spent her days making the mould ‘prepared from horse dung of which an immense quantity was to be pounded in a morter and sifted through a seaf’. When the mould cracked during casting, she started work on a new one. With no hint of disgust, she merely remarked that ‘it was an endless piece of work and served me for many hours’ exercise’.13

Living and sleeping inside a house dedicated to producing astronomical observations, she ‘became in time as useful a member of the workshop as a boy might be to his master in the first year of his apprenticeship’ – Caroline’s own words. Given her propensity to self-denigration, it seems clear that she worked far harder than any paid apprentice. As well as menial tasks, she was in charge of William’s notebook, crossing through the roughly written pages when she had made a neat copy. When Bath emptied during the summers, there was more time available for making instruments, and Caroline’s work intensified. Her duties, she remarked, ‘left me no time to take care of myself or to stand upon nicetys’, suggesting that she retreated from the world as William made more and more demands on her time.14

Systematic searching with a powerful telescope: that was William’s strategy, and on 13 March 1781 it paid off. Afterwards, he claimed that he would inevitably have discovered the planet Uranus sooner or later; like reading a book, he wrote, he simply turned the page that had the seventh planet recorded on it. But at the time he failed to recognise what he was looking at, and Caroline dutifully copied out his scrawled note of ‘a curious either Nebulous Star or perhaps a Comet’. In London, the Fellows of the Royal Society were stunned to learn about this provincial astronomer and his massive telescope, and Bath tourists started to include the Herschel household in their itinerary. When it became clear that this strange new star was a planet, William’s astronomical allies started negotiating on his behalf, and he was summoned up to London to meet George III. Like Caroline, he disliked being wrenched out of their private world. ‘Company is not always pleasing,’ he complained to her, ‘and I would much rather be polishing a speculum [a metallic mirror used in telescopes].’15 But he must have made a good impression, since he was awarded a royal pension so that he could give up teaching music and devote himself to astronomy.

Astronomy was William’s major priority, so he chose a house that was near Windsor and had outbuildings that could easily be converted. Caroline was appalled when she saw it. The roofs let in rain, the weeds were four feet high, and even getting there was difficult. Visitors preferred to arrive on Sundays, when the highwaymen were deterred by the large numbers of carriages flocking back to London after a weekend in the country. She soon discovered that their pension would not cover the high local prices, and money became a constant source of anxiety. As she virtuously economised, she came to perceive a world plagued by grasping, uncooperative people. Self-sacrifice slid into deliberate self-abasement as she prided herself on going without all but the most basic necessities. One of her few personal possessions was a worry-bead.

Alexander went back to Bath to continue his musical career, but Caroline decided that there was no turning back. She and William (with Alexander in the summers) spent every spare moment making mirrors and telescopes, many of which they sold, each with an instruction booklet carefully copied out by Caroline. Polishing the large mirrors was a time-consuming job, and for hours on end she docilely read novels to William, or popped food into his mouth so that he could work without interruption. With no time to change their clothes, ‘many a lace ruffle was torn or bespattered by molten pitch, &c.’ – presumably more housework for Caroline and the servants she had such difficulty in keeping.16 She stayed up with William at night, bringing coffee to keep them awake and busying herself in making measurements, copying out catalogues, tables and papers – sometimes in Latin – and helping to adjust the telescope’s position. They worked together in the dark, even when the ground was deep in snow. Plummeting temperatures sometimes froze the ink and once even cracked the metal mirror. ‘I know how feverish and wretched one feels after 2 or 3 &c nights waking,’ she later commiserated with her astronomer nephew.17

The full significance of her sacrifice hit her hard, and she consoled herself with work, at her brother’s beck and call ‘either to run to the Clocks, writing down a memorandum, fetching and carrying instruments, or measuring the ground with poles, &c., &c., of which something of the kind every moment would occur . . . In my leisure hours I ground 7 feet and plain mirrors from ruff to fining down and was indulged with polishing and the last finishing of a very beautiful mirror’.18 Perversely, she seems to have salvaged her pride by revelling in her own abnegation, even worrying about disrupting the observation schedule when, stumbling around in the dark on snow-covered ground, she fell over and tore open her leg with a meat-hook.

Instead of practising music, William and Caroline now worked hard at training themselves to look at the stars. Astronomers must be dedicated, proclaimed William – just like learning how to play Handel’s fugues on the organ. Music stands even provided the model for his telescope supports. He gave Caroline a small telescope of her own, a little sweeper that, by covering large sections of the sky at once, was ideal for comet-searching. She steeled herself to undertake solitary observations. Although she boasted about her fortitude when helping William, at first she was overwhelmed by ‘spending the starlight nights on a grass-plot covered by dew or hoar frost without a human being near enough to be within call’. But she persevered, becoming an expert who could recognise stars and nebulae by sight and so immediately detect any new comet that appeared. William rewarded her with a better instrument, although she was often kept so busy helping him that she had little time for her own research. But however much she complained about his interruptions, Caroline liked the security of knowing that her brother was close at hand. She converted herself into ‘a being that can and will execute his commands with the quickness of lightening.’19

A French traveller, entranced by the dream-like harmony of the strange household, stayed up with them all night and described their shared ritual of observation. Caroline sat quietly by the open window, studying an astronomical atlas, yet keeping her eye on a pendulum clock and a special dial linked by strings to the large telescope outside. William was perched on a platform at the top end of the telescope, which was slowly raised and lowered by a servant sitting underneath it. Freezing in the night air, Caroline noted down William’s shouted readings so that she could mark the stars on a chart, and yelled back instructions. ‘Brother, search towards the star Gamma’ she might say before resuming her work, and a subordinate would turn the telescope in a different direction.20 And when the morning came, she might grab a short sleep before continuing with her mathematical work, translating the numbers on her dial into degrees and minutes so that the stars’ locations could be mapped precisely.

Life was not always so tranquil. Orders for telescopes kept pouring in, and they worked desperately hard to fulfil them. After William became severely ill from long winter nights spent observing in the damp Thames air, they moved again, this time to Slough, where William immediately antagonised the neighbours by cutting down all the trees so that he could see the stars. Caroline suspiciously regarded all the local workers as thieves. Once again, the garden became a building site while a giant telescope, five feet across inside, was erected. It incorporated a special hut for Caroline, so that she could communicate with William through a speaking-tube. As it lay on the ground before being assembled, George III guided the Archbishop of Canterbury through the tube, exclaiming, ‘Come, my Lord Bishop, I will show you the way to Heaven!’21

Three months later, William had to deliver a telescope to Germany, and Caroline was left in charge. How should she fill the unaccustomed hours? At first, she diverted herself by polishing all the telescope brass. Then there was needlework, shopping and arguments with workmen (she knew they called her ‘stingy’). The next few weeks were spent in sweeping the skies, systematically recording her observations and carrying out the calculations needed to catalogue them properly. Boring, essential work, the sort on which she thrived, despite her moans.

But one night the bland routine was interrupted. Disguising her excitement, she fired off a letter to the Secretary of the Royal Society. ‘I venture to trouble you,’she wrote timidly, ‘with the following imperfect account of a Comet . . .’As the news spread, astronomers inspected her comet and wrote to her with warm congratulations for this unaided discovery. ‘I am more pleased than you can well conceive that you have made it,’ enthused one; ‘you deserved such a reward . . . for your assiduity in the business of astronomy.’22

When William came back, she resumed her satellite existence, revolving around her brother to promote his interests. His fame rested on Caroline’s accurate recordings of thousands of nebulae. As befits a scientific hero, he gained the reputation of being a selfless and charming man, but Caroline knew how his temper could flare up. A good publicity agent, she learned how to avoid angering him and managed his public image. While he was preoccupied with building yet another giant telescope, she controlled the financial arrangements. She also prepared his articles for publication, compiled lists of stars and carried out all the necessary calculations to complete unfinished catalogues. At night, they observed togther, Caroline by her open window, her brother at the viewing end of the telescope. And when visitors arrived, it was often Caroline who conducted the guided tour of the telescopes.

After fifteen years of servitude, Caroline did, at last, attain some sort of independence. For one thing, she was awarded an official salary from the King of fifty pounds a year to be William’s astronomical assistant. The arrival of the first quarterly payment was an important moment for her: ‘the first money in all my lifetime I ever thought myself at liberty to spend to my own liking’.23 In England, unlike France, even men were rarely paid for scientific research, and Caroline Herschel was probably the first woman ever to be in salaried scientific employment.

Independence brought its drawbacks. In her autobiography she left only a terse note that she was to lose her job as William’s housekeeper. She tore up ten years of bitter comments, but although her lines no longer exist, it’s easy to read between them: after William got married, Caroline was intensely jealous of her new sister-in-law. She demanded an independent salary during the marriage negotiations, which proved very tricky. Caroline rejected William’s financial support, his prospective bride worried about competing with astronomy, and he was reluctant to give up such a well-trained, indefatigable assistant.

Eventually a compromise was reached: his wife moved in with William, while Caroline lived in her own rooms above the workshops, later moving out to separate lodgings. Gossip circulated about the new Mrs Herschel’s wealth. When William took both women to a concert at Windsor, Fanny Burney snidely reported that ‘His wife seems good-natured; she was rich too! and astronomers are as able as other men to discern that gold can glitter as well as stars.’24 Caroline eradicated her own opinion from the record, but this unwanted liberation did leave her free for her own astronomical research, and she discovered eight comets, as well as several nebulae and star clusters.

William’s previous absence had enabled her to discover her first comet, and she immediately started sweeping the skies for more, especially when he was away travelling with his wife. A few months after the wedding, Caroline found her second comet, and immediately notified the Astronomer Royal, who sent her a long breezy letter in return. As she continued to find comets, her reputation spread. ‘Thus you see,’ marvelled the Astronomer Royal, ‘wherever she sweeps in fine weather nothing can escape her.’Although William often acted as intermediary, she also engaged in her own extensive correspondence with distinguished astronomers. By the seventh comet, she had even seemed to gain some confidence, informing the President of the Royal Society that ‘As the appearance of one of these objects is almost become a novelty, I flatter myself that this intelligence will not be uninteresting to astronomers.’25 Although she never entered the Royal Society’s buildings, three of her letters were published in the Philosophical Transactions – the first to appear under a woman’s name.

Caroline’s discoveries seemed more startling then than now not only because they had been made by a woman, but also because comets were very significant astronomical objects at the end of the eighteenth century. Many people still believed that comets were sent by God, direct messages of his anger at a sinful world. Mary Shelley boasted about her auspicious birth immediately after one of Caroline Herschel’s comets had blazed in the sky.26 Astronomers denounced such beliefs as irrational superstition: they were keen to demonstrate their own scientific superiority by showing how comets followed precise mathematical laws. Émilie du Châtelet’s translation of Newton’s Principia had appeared immediately after French mathematicians had successfully predicted the return of Halley’s comet in 1759, but more evidence about the behaviour of comets was still needed to confirm the theoretical work. All over Europe, astronomers observed Caroline Herschel’s comets in order to calculate their orbits. The director of Paris’s Royal Observatory, who had met her on a visit to Slough and was renowned for his own comet discoveries, wrote promising to keep tracking her comet and send over his results. ‘She will soon be the great Comet finder,’ enthused one of William Herschel’s friends, who chauvinistically hoped that she would beat the Parisian observers.

Joseph Lalande, one of France’s most famous astronomers, was exceptionally supportive. ‘At the moment,’ he wrote to her, ‘comets are what interest astronomers most. We are expecting several from you.’ Unlike his English counterparts, Lalande actively promoted women astronomers. He was still mourning the death of Caroline Herschel’s French equivalent, Hortense Lepaute, who had performed many of the laborious calculations needed for the 1759 prediction. Lalande christened a new baby Caroline (sister to Isaac, Newton’s namesake), reporting in a national gazette that he couldn’t have chosen a more illustrious name. In his book on women’s astronomy (which was translated into English), he reminded his male colleagues that women’s ‘abilities are not inferior, even to those of our sex who have attained the greatest celebrity in the sciences.’27

Despite her international renown, Caroline was still willing to take on tedious tasks for William. The major British star catalogue had been published seventy years earlier under the name of Johannes Hevelius’s rival John Flamsteed, but there were many mistakes – some stars were missing, while others were recorded with the wrong brightness. Caroline was the obvious candidate for the demanding, boring task of correcting the errors. She had already compiled much missing data, but now William suggested that she draw up an Index to make it easy to refer from the catalogue to Flamsteed’s original observations. Twenty months of hard, tedious work. Did she know that Flamsteed’s wife Margaret Cooke had, like her, been involved in this catalogue? And that Elisabetha Hevelius had finalised and published her husband’s atlas?28

Caroline might have used William’s marriage to prise her freedom, but, by now conditioned into servitude, she found herself unable to escape. Although she was making independent discoveries, in other ways she was more enslaved than ever. On the surface, William’s two women overcame their initial hostility to become very friendly, yet Caroline’s diaries imply a different story. For twenty years she moved between the observatory at Slough, a succession of lodgings and Alexander’s house at Bath, a trajectory that seems as though it were designed to ensure that she encounter her sister-in-law as little as possible.

While William and his wife travelled round the country visiting friends, Caroline was left behind to earn her salary. Rather than describing the purposeful life of an independent woman, her diary entries suggest the haphazard motion of a subordinate who travelled round England to look after empty houses and cope during astronomical crises. One year, she went to Bath in July and came back to William’s house in November; after dinner on the first evening, she started work copying out his latest astronomical article. About a week later, the rest of the family went to Bath, leaving her alone until they came back; the next day, she decamped to a nephew’s house. The opening entry for 1813 gives the flavour of her life: ‘The three last months of the preceding year I spent mostly in solitude at home, except when I was wanted to assist my brother at night or in the library.’29

By 1817, William was so ill, old and depressed that Caroline ‘felt my only friend and adviser was lost to me’. She slogged on, sorting out papers, helping her brother when he was well enough to work, but more often watching in dismay as his hands trembled over the backgammon board. While the family was away in Bath, she moved in to make an inventory, but when William got back he showed no interest in her efforts. As he declined, she made herself sick with worry, returning each day ‘to my solitary and cheerless home with increased anxiety for each following day’.30 What should she do, she fretted, where should she go? William lingered on until 1822, and by then she had made up her mind – she would return to Germany.

She left in a great rush, not even waiting until all the funeral arrangements were completed. Did she panic, stunned by William’s death? But it was hardly unexpected. Even though the courteous correspondence apparently reveals devoted relatives, her decision to depart so abruptly does suggest unbearable family tensions. Certainly she was unhappy once she got back to Hanover. Right from the beginning, she rarely went out, ‘and what little I have seen of Hannover . . . I dislike!’ Still, she told her nephew John, even this dreary existence was better than staying in England ‘where I should have had to bevail [sic] my inability of making myself useful’.31 Her letters to her sister-in-law and her nephew are masterpieces of emotional blackmail: a pity I haven’t heard from you yet, I feel so ill and lonely here, my relatives are such nasty people, if only I was in the fresh English air . . . for twenty five years Caroline sent a constant stream of letters back to England, packed with complaints and regrets. Guilt-tripping is a modern expression, but the concept existed long ago.

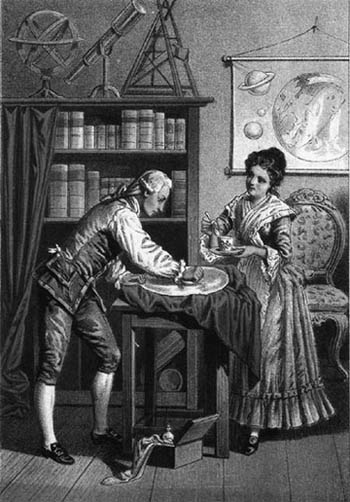

She transferred her adoration to William’s son John, making him the new centre of her life, and justifying her own existence solely through her usefulness to him. She sifted through the English newspapers – two months old by the time she got them – for any mention of his name, sent him books and papers, repeatedly burdened him with the information that he was her only purpose for living. Suffering from failing eyesight (see Figure 23), and hemmed in by tall buildings, she could not use the telescope that she had installed in her rooms as a monument to the past. Instead, she embarked on yet another catalogue, this time of the nebulae and star clusters that William had observed, intending her work not for publication but for John’s personal use to advance his own astronomical career. Day after day, she worked her way through 2,500 sets of calculations. A labour of love, to be sure, and extremely useful, but also the means for an obsessive, unhappy old woman to obliterate her surroundings and survive vicariously through the men in her family. She seemed determined to be miserable, reflecting only on the past and even regretting John’s achievements in case they detracted from William’s fame. In the autobiography she started when she was eighty, the very first sentence is about William.

Fig. 23 Caroline Herschel. Etching by G. Busse, Hanover, 1847.

Almost a hundred when she died, Caroline became celebrated for her longevity as well as her achievements. She received official awards from London’s Royal Astronomical Society and the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin. Presumably she felt some pride in this belated recognition, although when she received her medal from London she ungraciously claimed to have felt ‘shocked rather than gratified . . . for I know too well how dangerous it is for women to draw too much notice upon themselves’.32 When she was ninety-six, the King of Prussia sent her a gold medal, and for her next birthday the Crown Prince and his family arrived to present her with a large velvet armchair. Since she entertained her guests with a song by William, it seems likely that her beloved brother formed a major topic of conversation.

Soon afterwards, she insisted on leaving the comfort of her sofa to pose upright for the drawing shown in Figure 23. Unsurprisingly, this self-effacing woman left very few portraits, but this one pays tribute to her continued interest in astronomy. As she points to a map of the solar system, her finger rests on the gap between Mars and Jupiter, a zone of great interest to contemporary German astronomers. Like her, they focused on picking out unexpected objects absent from the star catalogues, and were trying to distinguish between comets and small planets. With her failing eyesight, did she realise that Uranus lies way beyond the edge of the paper? For once, the picture is about her, not William.

Caroline Herschel always claimed that she undertook her chores solely for her men’s benefit, but occasionally she let a glimmer of self-satisfaction escape. Perhaps, she once remarked, she deserved recognition for her ‘perseverance and exertions beyond female strength’. Another time, she allowed herself a rare expression of pique at male oppression in a letter of thanks to the Astronomer Royal for arranging the Royal Society’s publication of her Flamsteed Index. ‘Your having thought it worthy of the press has flattered my vanity not a little,’ she started politely. But this time her gratitude came with a sting in the tail: ‘You see, sir, I do owe myself to be vain, because I would not wish to be singular; and was there ever a woman without vanity? or a man either? only with this difference, that among gentlemen the commodity is generally styled ambition.’33

There was Caroline’s dilemma – she wanted to blend in, to be like other women, yet at the same time she contemptuously shunned their company and involved herself in masculine activities. In some ways, she had escaped the confines of her German upbringing to become an independent, successful astronomer. She earned a scientific salary, was friendly with the most eminent astronomers in England and France, and had published her comet letters and catalogue with the Royal Society. Nevertheless, she was trapped in her conventional belief, ingrained since childhood, that women should be subservient to men. ‘All I am, all I know, I owe to my brother,’ she stressed repeatedly; ‘I am only the tool which he shaped to his use.’34

Male astronomers, she wrote, were the huntsmen of science, while she was merely a pointer, eagerly awaiting friendly strokes and pats from her masters. This sporting simile immediately summons up the British gentrified life that surrounded her in the Windsor countryside, and she retained this canine imagery long after she had returned to Germany. She coined various versions of her famous comment that ‘I did nothing for my Brother but what a well trained puppy Dog would have done: that is to say – I did what he commanded me.’35

This remark makes modern women squirm, yet two centuries ago it carried somewhat different connotations from today. Because animals played crucial economic roles in transport and agriculture, dogs were encountered far more frequently in daily life and, correspondingly, canine imagery appeared more often – to fortify William Herschel against critics, one of his colleagues advised him to ‘mind not a few jealous barking puppies’. Dogs and people had not yet, however, accommodated themselves to living together in cities. Hanover, complained Caroline, was plagued by ‘the intolerable Newsance of the barking of dogs’, relieved only when owners were compelled to muzzle them ‘like Bears’.36

As Anne Conway’s portrait (see Figure 15) illustrates, dogs were important possessions. Men regarded themselves as the pinnacle of God’s creation, set on Earth to rule over and tame lesser beings. Like animals – men claimed – women were governed by their passions and needed to be controlled. In pictures, they were shown together, twin models of fidelity and obedience to their master. Mary Wollstonecraft railed against the subservience exhibited by women like Caroline Herschel. ‘Considering the length of time that women have been dependent,’ she wrote, ‘is it surprising that some of them hunger in chains, and fawn like the spaniel?’37

Painfully aware of her awkwardness, Caroline was concerned about alienating friendly colleagues. ‘I have too little knowledge of the rules of society,’ she worried, ‘to trust much to my acquitting myself so as to give hope of having made any favourable impressions.’ Like many outsiders, she seems almost to have cultivated her strangeness as a defence against a world she perceived as hostile. ‘I don’t tell Fibs though they may not always like to hear what I say,’ she wrote defiantly.38

Men could cultivate eccentricity as an attribute of genius, and were free to indulge their scientific passion at the expense of normality. In contrast, unusual women were pariahs. ‘There is hardly a creature in the world more despicable or more liable to universal ridicule than that of a learned woman,’ wrote Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who was renowned for introducing smallpox inoculation. Clever women were not just breaking the bounds of social convention. They were, it was believed, defying their inherent make-up, and so ran the risk of being regarded as freaks of nature. Montagu was speaking from painful experience when she recommended that her granddaughter should ‘conceal whatever Learning she attains, with as much solicitude as she would hide crookedness or lameness’. Lalande once addressed Caroline Herschel as ‘Learned miss’ in English at the beginning of a letter in French; he did not realise that this could be an insult.39

Caroline Herschel avoided the slur of brilliance by moving beyond reticence into taciturnity and converting modesty into self-abnegation. But she suffered. She rejected the friendship of women, most of whom she denigrated as stupid, and so was an outcast amongst her own sex. On the other hand, there was no place for her in the world of men. A fond niece in Germany seemed to be relieved when Caroline Herschel died because, she wrote, ‘now the unquiet heart was at rest.’40