The Men, by thinking us incapable of improving our intellects, have entirely thrown us out of all the advantages of education; and thereby contributed as much as possible to make us the senseless creatures they represent us. So that, for want of education, we are render’d subject to all the follies they dislike in us, and are loaded with their ill treatment for faults of their own creating.

Sophie, Woman Not Inferior to Man, 1739

It was on a dreary night in November . . . one of English literature’s most famous opening lines. It first appeared in 1818 to introduce the dramatic scene when Victor Frankenstein infuses life into the creature he has assembled from illicitly gathered body parts.1 They were the first words Mary Shelley (1797–1851) committed to paper after a troubled night of waking nightmares that inspired the plot for her extraordinary novel, Frankenstein. Confined to a house in Switzerland by the rainy weather, Shelley and her travelling companions were involved in a competition to terrify each other by telling ghost stories. To her embarrassment, she could think of nothing suitable to hold the group’s attention. Late into the night their conversation had ranged over recent experiments and discoveries – the new electric batteries that galvanised corpses into action, Erasmus Darwin’s desiccated creatures that wriggled vigorously after soaking. Was it possible, the friends wondered, that science could solve the biggest question of them all, the nature of life itself? When Shelley eventually went to bed, her imagination feverishly conjured up a horrific scene. At last she had a tale that would enthral her friends.

Although created less than 200 years ago, Frankenstein has become a mythical figure. Everyone knows his story – or do they? Mary Shelley’s original book, first published in 1818, was very different from modern versions. Shelley herself rewrote substantial sections, cutting out a lot of the science and adding sentimental chunks to soften the punch of her message. A century later, Boris Karloff created the definitive film icon of a hatchet-faced monster with bolts through its neck – but this was a parody of Shelley’s sensitive progeny racked by remorse. More recently, the publicity for Kenneth Branagh’s production advertised its authenticity, even though there were substantial changes in the plot. This is a brief outline of the first edition of Frankenstein . . .

Like a set of Russian dolls, in Frankenstein three people’s stories are embedded one within the other. The outermost wrapping concerns Robert Walton, a polar explorer who rescues an emaciated, near-frozen stranger and brings him back to life. Unlike later episodes, this is a normal process of revival, using brandy, warmth and food. The narrative of this unexpected visitor, Victor Frankenstein, forms the next layer in . . .

Here the resuscitation is more artificial and sinister. After studying different types of science, Frankenstein plunders dissecting rooms and charnel houses to construct an eight-foot human replica, whom he mysteriously transforms into a living being. This had been Shelley’s night-time inspiration – the creator kneeling appalled as his horrendous handiwork stirs into life. Rushing from the room in disgust, Frankenstein abandons science, succumbs to weeks of fever, and then struggles to resume normal activity. But six months later, the nightmare erupts again. The creature kills Frankenstein’s little brother, and a servant is unjustly hanged. Frankenstein is horrified, but when he discovers his daemon, consents to hear his version of what has happened, which comprises the core of the book . . .

Misery and rejection, not innate evil, drove the fiend’s monstrous behaviour. Sheltering next to a cottage, he had secretly helped a humble family to survive and, by eavesdropping on their conversation, learned first how to talk, and then how to read. His ghastly appearance conceals a truly civilised character, yet he repulses everyone he tries to befriend and despairs of being condemned to a life of isolation. Murder is his weapon of revenge, a way of blackmailing Frankenstein into creating a female companion to lighten his lonely existence. He extorts the promise of a partner from his listener, who resumes his own story . . .

Although Frankenstein does start to collect the ingredients for a woman, he destroys his half-finished work in disgust. The avenging creature kills first his closest friend, and then – deprived of a wife for himself – strangles Frankenstein’s beloved cousin Elizabeth on the night of their marriage. Racked with self-hatred, Frankenstein dedicates himself to killing the fiend that he has generated. Ineluctably bound to one another, the monstrous couple roam across Russia and up into the Arctic north, until they are separated by a crack in the ice. Hovering at the edge of death, Frankenstein now persuades his own listener, Walton, to pursue the creature and kill him . . .

Under pressure from his crew to turn southwards to safety, Walton breaks his promise to Frankenstein, who dies. The book closes as Frankenstein’s demonic progeny, now a martyr who repents of his evil deeds, disappears northwards across the icy waves to sacrifice himself on his own funeral pyre.

Frankenstein is fiction, but it is also a historical document packed with information about attitudes towards science and women in the early nineteenth century. As one of Shelley’s first reviewers commented, Frankenstein ‘has an air of reality attached to it, by being connected with the favourite passions and projects of the times’.2 Together with its countless reinterpretations, Frankenstein is one of the most heavily studied novels in the English language, and yet – like all enduring myths – there is always something new to learn from it.

Where do the boundaries lie between science and imagination, between fact and myth? The distinctions are blurred because there are different sorts of truth. Mythical heroes may engage in imaginary exploits, but their moral dilemmas are rooted in real-life ethical choices. Conversely factual accounts of the physical universe sometimes turn out to be less objective than scientists claim. Many of the events in Shelley’s book could not possibly have happened, but, like fairy stories, they seem to take place in an adjacent world that resonates with our own hopes and anxieties. Her larger-than-life actors are slightly unreal, yet their unfolding story carries warnings about how our own lives should be conducted.

Shelley could not have foreseen how her novel would be twisted to fit scary scenarios lying ahead in the future. However, she certainly did appreciate the power of mythical stories. Classical legends were far more familiar then than now, and the basic characters and plots were instantly recognisable. The full title Shelley chose for her scientific fiction was Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus. Her contemporaries knew that Prometheus had made the figure of a man from clay and then, with the help of Athene (Minerva), had stolen the secret of fire from the gods so that he could infuse his statue with life. They also remembered that Prometheus was the grandson of Uranus, the planet discovered by William Herschel – an especially important link for Shelley, who credited her beautiful complexion and fine haze of hair to her birth beneath one of Caroline Herschel’s comets. Romantic poets often identified themselves with Prometheus as a saviour/creator figure. Particularly during the French Revolution, Prometheus became a symbol of rebellion against tyranny; it was only later that he came to represent a warning against human ambition.

Conservatives condemned Frankenstein because it frightened them. In the Bible, it was God, not Frankenstein or Prometheus, who had made Adam out of dust and breathed the fire of life into his nostrils. Scientific research promised so many rewards, yet surely it was sacrilegious to suggest that a mere mortal could create life? Shelley’s Frankenstein still evokes people’s deepest fears of disease, revolution and disaster, and it also seems to foretell future scientific catastrophes. The story remains so powerful because, like the myths on which it is based, it has repeatedly been retold. Resembling other fictional characters who verge on reality – Faustus, Don Juan, Sherlock Holmes – Victor Frankenstein and his creature have taken on lives of their own as, time and again, they have been reinterpreted. Stripped of Shelley’s original subtleties, the evil scientist and the demonic monster have symbolised one threatening evil after another – Irish nationalism, the atomic-bomb project, transplant surgery, and now the ‘Frankenfoods’ produced by genetic modification.3

When Shelley created Frankenstein, the modern Prometheus, she wrote a scientific morality tale, the modern equivalent of a religious parable. She may also have been thinking about the second part of this story, familiar then, but now less well known. Zeus wanted to punish the human race for Prometheus’s transgression, and he himself gave life to a clay statue. Zeus’s creation was not a man, but a woman – Pandora. At her birth, the Olympian gods taught Pandora all the female virtues, but when she was presented as a gift to Prometheus’s brother, Pandora lifted the lid from her giant vase and unleashed evil throughout the Earth. Only Hope remained inside her casket.

Shelley was strongly influenced by her father, the radical reformer William Godwin. When she was little, he used her and the other children of the household as test readers for his books. In one of these, he outlined the linked Prometheus/Pandora story. ‘The fable of Prometheus’s man, and Pandora the first woman, was intended to convey,’ he wrote, ‘to how many evils the human race is exposed; how many years of misery many of them endure . . . how many vices are contracted by man, in consequence of which they afflict each other with a thousand additional evils, perfidy, tyranny, cruel tortures, murder, and war.’ Modern readers forget how closely the stories of Prometheus and Pandora are tied together, yet Godwin’s summary reads like an outline of his daughter’s Frankensteinian nightmare.4

Victor Frankenstein was a figment of Mary Shelley’s imagination but, like real-life women/men couples, their partnership reveals contemporary attitudes towards women and science. Shelley was well informed about the latest scientific debates, and Frankenstein was an astute study of the society in which she lived. By the end of the eighteenth century, science had become a fashionable topic, and educated readers – women as well as men – were knowledgeable about at least the basic principles.

Even though female authors were unable to embark on active careers within science, their educational books were enormously important because they presented scientific knowledge in a way that everybody could understand. As a result, science was no longer an arid esoteric subject limited to a privileged few, but was an important part of nineteenth-century culture. During the eighteenth century, men had cashed in on female wealth by writing patronising, simplified books that treated women as consumers of science. By the middle of the nineteenth century, some women were supporting themselves (and their dependants) by writing scientific books read by both the sexes. Education seemed to be suitable work for women, who were not deemed sufficiently original to generate their own ideas, but were at least clever enough to understand and explain the achievements of others.

Conventional scientific texts and imaginative works of literature are often seen as lying on either side of an impermeable boundary. More realistically, they can be viewed as marking opposite ends of a continuous spectrum. Ethical problems of science were aired not only in political debates and learned journals, but also in fiction. Reciprocally, scientific authors devised fictional settings to engage their pupils’ interest. Priscilla Wakefield’s Introduction to Botany certainly wasn’t a novel, but neither was it a dry collection of facts. By inventing characters such as Felicia, Constance and the motherly Mrs Snelgrove, she was – like other writers – blurring the division between fact and fiction. Spread out between the fact/fiction poles lay educational books like Wakefield’s and Bryan’s that relied on fictional scenarios, and also fictional books that relied on scientific arguments – novels like Maria Edgeworth’s Belinda (which included another dig at Thomas Day’s educational experiments) and Frankenstein.5

Although there were plenty of opportunities for women to learn about science, they were not encouraged to embark on laboratory experiments. As a woman, Shelley was restricted to observing science rather than participating in it, but she did learn science from her husband Percy. He had been a keen experimenter while he was a student at Oxford and still kept up with the latest research. For his twenty-sixth birthday, she gave him a hand-stitched balloon and a telescope, which they bought together in Geneva. A voracious reader, she borrowed his textbooks and kept up-to-date with scientific issues being debated in the journals. However, whereas Percy Shelley had had hands-on training at school, this experience was denied to Mary Shelley.

Shelley’s father planned to teach her ‘some smattering of geography, history and the other sciences’, and for part of her childhood Shelley studied these more technical subjects at home with a governess and a tutor. Specific details have not survived, but her teachers would almost certainly have given her some of the little conversational books on science being written explicitly for girls by Wakefield, Bryan and other female authors. And for chemistry, the most likely fictionalised account for Shelley to have read was Jane Marcet’s Conversations on Chemistry.6

Jane Marcet, the daughter of a wealthy Swiss banker, was one of the most influential scientific writers amongst the generation after Wakefield. Instead of botany, the conventional safe science for women, she chose to write about chemistry, one of the sciences central to Frankenstein. Marcet set up her books as cosy dialogues between Mrs B and two young girls. (Although the link is probably coincidental, Margaret Bryan’s frontispiece (Figure 28) does seem marvellously apt.) By fictionalising her presentation, Marcet created new audiences for science and so helped to establish its importance.

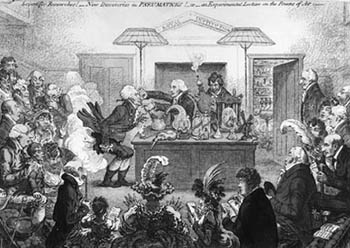

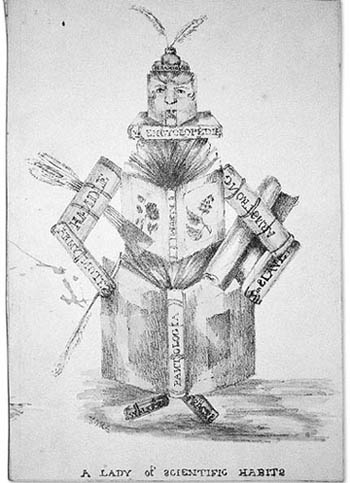

When Mary Shelley was writing Frankenstein, for chemical information she chose the same scholarly source as Jane Marcet – Humphry Davy, a young lecturer at the newly founded Royal Institution (Figure 29). In James Gillray’s caricature, Davy menacingly clutches a pair of bellows and hovers behind the professor who is forcing his exploding victim to inhale laughing gas (nitrous oxide) from a series of flasks. Davy attracted hundreds of people to his lectures, but the savagery of Gillray’s humour indicates how tenuously Davy clung to his position. Traditionally chemistry was the poor relation of physics and mathematics, disparaged as a practical rather than a theoretical subject. In addition, since Lavoisier’s revolutionary changes, chemistry had become associated with political radicalism and dangerously progressive thinking.7

Fig. 29 Scientific Researches! – New Discoveries in Pneumaticks! – or – an Experimental Lecture on the Powers of Air. Hand-coloured etching by James Gillray, 1802.

Davy wanted to demonstrate how new chemical techniques could probe deep into the nature of matter, but his critics accused him of introducing too much spectacle. Unlike the Royal Society, the Royal Institution was – in principle, at least – open to the public, and Gillray has satirised the members of the audience as cruelly as the performers. The lower-class people to the left gawp in amazement, while the fashionably dressed couple at the front are assiduously taking notes. Conservative observers sneered at these educational aspirations. Samuel Taylor Coleridge worried about the slippery slope that would result in debasing knowledge by making it available to all. ‘You begin, therefore, with the attempt to popularise science,’ he warned – ‘but you will only effect its plebification.’ Coleridge’s friend Robert Southey divided the spectators at the Royal Institution into two groups – bored men and superficial women. ‘Part of the men were taking snuff to keep their eyes open,’ he reported, ‘others more honestly asleep, while ladies were all upon the watch, and some score of them had their tablets and pencils, busily noting down what they heard, as topics for the next conversation party.’8

Although Marcet might seem to be unimportant because she was a children’s writer, her work had vital impacts on nineteenth-century science. She was not a passive transmitter of diluted science. On the contrary – by focusing on chemistry for women, she changed the ways in which science itself was understood and performed. In her chatty little books, a woman and two girls practise chemistry at home, the conventional place for women. By creating this fictional setting, Marcet converted Davy’s showy demonstrations into a safe domestic activity that anyone could tackle. Davy made chemistry appear exciting, dangerous and politically risky – definitely a subject for men rather than women, and far from being a sober science. But by making chemistry respectable, and even safe enough for girls, Marcet helped to make it central. No longer relegated to the scientific margins, chemistry became a subject that enabled far more people than ever before to participate in scientific investigations.

Married to a Fellow of the Royal Society Marcet belonged to a group of educated women who transformed science communication. Many of them the wives and daughters of eminent scientific men, they were related to one other in extended intellectual networks resembling royal dynasties. These women were vital for the development of science in the early nineteenth century. Marcet was very friendly with Maria Edgeworth, who had a special reason to be grateful – when her sister accidentally swallowed some poison, Edgeworth remembered Marcet’s lessons in Conversations on Chemistry quickly enough to prescribe a life-saving chemical remedy. Marcet was also close to Mary Somerville, whose lucid explanations of complex French physics made the latest research accessible to science students – men as well as women. Rather like the literary bluestocking circles of the eighteenth century, women like Mary Somerville, Jane Marcet, Mary Lyell and Maria Edgworth formed their own close female groups, exchanging scientific news and providing each other with practical and emotional solidarity.9

Marcet’s Conversations on Chemistry was a huge success. The book first appeared in 1806, but ran through sixteen editions during the next forty years and was twice translated into French: in the United States alone, 160,000 copies were sold. Many thousands of scientists must first have learned their chemistry from Marcet, but her most famous pupil was Michael Faraday, founder of electromagnetism and Davy’s successor at the Royal Institution. As a young bookbinder’s apprentice, Faraday taught himself chemistry by reading Marcet’s Conversations in the evenings after work. Long after he became one of England’s most prestigious scientists, Faraday sent Marcet copies of his scholarly articles and praised his first teacher for giving him great pleasure at the same time as writing accurately. By capturing his imagination, Marcet had drawn Faraday into the world of facts. Marcet initially wrote for women, but – like other female scientific authors – she dramatically affected the very nature of science itself.

Nevertheless, being a scientific woman demanded a thick skin. By presuming to enter the masculine territory of science, women were transgressing conventional boundaries. It was not only men who drew intellectual distinctions between the sexes – many women also worried that engaging in academic activities would detract from their femininity. ‘All women possess not the Amazonian spirit of a Wolstonecraft,’ campaigned one of her female critics, Mary Radcliffe. She warned that overturning male oppression might entail ‘throwing off the gentle garb of a female, and assuming some more masculine appearance’.10 Correspondingly, pictures portrayed Minerva, the goddess of wisdom, as a muscular, heavy-set woman – a masculine goddess to indicate that learning was associated with men.

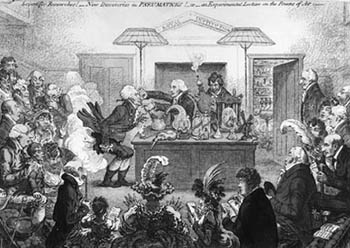

Fig. 30 A Lady of Scientific Habits. Lithograph, early nineteenth century.

New images appeared to back up the moralising books, articles and lectures that prescribed appropriate behaviour for women. In the frontispiece to her book on astronomy, Bryan had shown herself holding a pen (Figure 28), but the print reproduced in Figure 30 mocks female pretensions to authorship. This writer’s inkwell is ludicrously planted on top of her head, and a sheaf of quills is precariously balanced beneath her arm. ‘The lady of scientific habits’ is a travesty of femininity. Drawn in straight lines rather than curves, she wears a skirt compiled from Pantalogia, a twelve-volume encyclopaedia and here a pun on men’s trousers. The other tomes also play verbally on books and the body – Walker’s Tracts for her feet, Armstrong’s On Slavery for her left arm, Army Notes for the other. In place of her breasts are two flowers, which indicate the contents of the Album covering her chest. Far from being an advertisement for scientific botany, this lady was herself designed to be stuck inside an album, along with pressed flowers, drawings and verses. This whimsical parody of intellectual dedication signalled to women the unfortunate consequences of devoting themselves to scholarship.11

The old stereotypes were still being reinforced: scientific learning for men, domestic skills for women. Although women were campaigning for better female education, their demands were very different from those of modern feminists. Most of them agreed that women’s minds were different from those of men, inherently less suited to the methodical work required in science. ‘We are not formed for those deep investigations that tend to the bringing into light reluctant truth,’ maintained the novelist Laetitia Hawkins. She backed up her argument by pointing out the unflattering effects of concentrated thought – a furrowed brow and fixed gaze lent dignity to a man, but could only detract from a woman’s soft features. Marriage and motherhood were sacrosanct even for Wollstonecraft, while educators like Wakefield and Bryan stressed that a woman’s place lay at home. ‘Each sex has its proper excellencies,’ observed the conservative Hannah More, as she fought to retain the status quo. Surely, she asked, women should continue in their allotted roles, rather than challenge God’s will by attempting to emulate the work of a man?12

Hardly surprising, then, that Marcet and other women decided to publish their scientific textbooks anonymously. At first, Frankenstein also appeared anonymously, although it did bear two men’s names – William Godwin and Percy Shelley. Mary Shelley dedicated her book to Godwin, her father, which might have given a strong hint of the author’s identity. But the preface was written by Percy Shelley, and many readers inferred that he had written the whole book – including Sir Walter Scott, to whom she proudly revealed the truth.

Some of the early reviews were vicious. Shelley left England soon after the publication date, so hopefully she never read that her book was ‘the foulest Toadstool that has yet sprung up from the reeking dunghill of the present times’. But sales were high, and five years later the second edition did carry her name on the title-page. Critics were astonished at this female feat. ‘For a man it was excellent,’ exclaimed one reviewer – ‘but for a woman it was wonderful.’13

Literary analysts often hail Mary Shelley’s book as the first in a new kind of literature – science fiction. Frankenstein was not, of course, intended to be a documentary. Nevertheless, it was solidly based on cutting-edge scientific research into polar exploration, electricity and chemistry. Shelley’s novel was shocking precisely because it wavered on the edge of feasibility. Modern alarmists celebrate Frankenstein for its prescient warnings of subsequent scientific disasters and dilemmas, but Shelley produced a commentary on the present as much as a manifesto for the future.

Using fiction, Shelley explored the doubts hovering around science’s respectability. Scientific men felt insecure, unstable: they had no fixed identity, no career structure, no professional organisations to support and advise them. Sceptics questioned whether ambitious scientific projects could be reconciled with the orderly behaviour and clear, logical thought expected of a gentleman. Conventional scholarship belonged in gentlemen’s studies, and was (supposedly) pursued for the sake of abstract knowledge and human welfare. Scientific research, on the other hand, entailed travelling overseas and demanded manual work of the type formerly reserved for labourers and servants. Some men even expected to be paid for their work or rewarded for their inventions! Educated women presented another challenge. Surely allowing them to engage in science would threaten its exclusivity, would diminish its appeal as a prestigious activity for privileged men?14

The three layers of Frankenstein probed the public value of scientific research from different angles. Reading the novel’s outer framework, it is clear that Shelley had been keeping up with the latest scientific discussions about magnetism and polar voyages. Foreign travel boomed after Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, and the press was packed with articles discussing the advantages of Arctic exploration. Her fictional Walton personified a new type of celebrity – the scientific explorer. In the past, military champions had been hailed as the nation’s heroes. Now their place was being taken by adventurous young men who set out to conquer the world by gaining knowledge rather than taking over territory and people.

Walton romanticised the aspirations of scientific investigators and also of naval administrators. Far from being the disinterested pursuit of pure knowledge, scientific exploration was indelibly tied to commercial and imperial profit. Propagandists advertised the importance of scientific research for improving navigation and exploiting the resources of overseas colonies. Government, commerce and science went hand in hand as Britain expanded her empire. As a leading Admiralty official put it, searching for the North Pole was essential for extending ‘the sphere of human knowledge’; and, he continued, ‘Knowledge is power.’15 Knowledge is power: a direct quote from Francis Bacon, and one that made the goals of modern science sound dangerously like the dreams of those ancient mystics and alchemists whose works Frankenstein had studied with such fascination.

Scientific research was being promoted for its financial rewards, but contemporary questions about the moral cost of progress thread through the central sections of Frankenstein. At the newly founded Royal Institution, Davy – in an expression reminiscent of Bacon – had boasted that experiments enabled a man ‘to interrogate nature with power, not simply as a scholar, passive and seeking only to understand her operations, but rather as a master, active with his own instruments’. For him, the electric battery was not only a miraculous new source of energy, but also ‘a key which promises to lay open some of the most mysterious recesses of nature’.16Like Bacon’s earlier followers, Davy wanted not only to learn about female nature, but also to search out her secrets and control her.

But Davy also cautioned against scientific speculators who promised too much. ‘Instead of slowly endeavouring to lift up the veil concealing the wonderful phenomena of living nature,’ he warned, ‘they have vainly attempted to tear it asunder.’17 The veil of nature: an old and familiar image. How could scientific experimenters gain prestige by promising rewards from their research, yet avoid ripping away the veil like over-confident magicians? When she evoked Frankenstein’s inner turmoil, Shelley tapped into these subterranean anxieties.

Davy was important to Shelley’s writing both for his scientific ideas and for his iconic status. She studied his work while she was creating Frankenstein, and she must also have come across many references to him in other books and articles; she may perhaps have attended one of his lectures at the Royal Institution. Davy was England’s leading expert on electrochemistry. An energetic self-promoter, he advertised how electric batteries, which had only recently been invented, could reveal new elements and pick apart the chemical processes that were fundamental to life.

Unlike older scientific topics, such as mechanics and mathematics, electrochemistry was new and exciting, tinged with political threats as well as experimental risks. In one of his lectures that Shelley studied, Davy sketched out a Frankensteinian vision. Electrical research, he claimed, has not only shown the chemist how to understand the world, but has also ‘bestowed upon him powers which may be almost called creative; which have enabled him to modify and change the beings surrounding him’. Other chemists also wrote with messianic fervour. ‘We are now admitted,’ enthused an eminent Scottish professor, ‘into the laboratory of nature herself.’18

Experimenting in his own laboratory of nature, Frankenstein discovered the secret of life. As with polar exploration, Shelley was not just fantasising about science, but was fully up-to-date on contemporary issues. While she was writing Frankenstein, the old debates about the nature of life had reached a particularly acrimonious peak. At one extreme lay the materialists, who insisted that life lay in matter itself and was just a question of somehow rearranging fundamental building-blocks. Their opponents objected to any such suggestion that life could originate in a chemical process. Surely, they argued, life cannot just be a result of how atoms and cells are organised, but must depend on some soul or spirit that is infused by God. John Abernethy, a prominent London surgeon, had recently proposed a compromise between these two opposing camps in the vitalism controversy, the scientific reductionists and the religious traditionalists. Perhaps, he suggested, the source of life might be some superfine invisible substance, analogous to electricity.

Electricity – could this be the secret of life itself? It was a captivating idea. Since Shelley was a small child, doctors had been claiming that dead people could be revived by passing strong electric currents through them, and a few successes were reported after cases of drowning. At last it seemed as if the medical dream of resuscitating the dead might be attainable. In one particularly famous London experiment on a newly hanged criminal, spectators watched as the corpse’s eye leered open, his clenched fist rose into the air and his legs kicked violently while his back arched. Similarly, Shelley described how, using his ‘instruments of life’, Frankenstein managed to ‘infuse a spark of being’ into the inert assemblage of limbs and organs that he had sewn together; he watched ‘the dull yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed hard, and a convulsive motion agitated its limbs’.19

One of Abernethy’s most outspoken critics was his former pupil William Lawrence, who was a friend of the Shelley couple as well as their medical adviser. Accusing Abernethy of fudging the issues, Lawrence ridiculed his suggestions that electricity could stand in for the human soul. Whether superfine or coarse, insisted Lawrence, matter is matter, and that is where life is to be sought – there is no magic moment of creation when a mysterious vital force is somehow infused into inert material. Shelley signalled her allegiance to Lawrence by portraying Frankenstein – representative of the Abernethy faction – as a blundering experimenter whose ambitions failed.

In telling her story about Frankenstein, Shelley ruminated on the fate of science and peopled her fiction with scientific stereotypes. Shelley’s only survivor is Walton, the romantic dreamer who has renounced poetry and turned instead to scientific exploration. With soldierly dedication, he has toughened his body and trained his mind before setting off with child-like curiosity to investigate the frozen north. Although fired with utopian ecstasy, unlike Frankenstein, Walton does not tamper with the powers of nature but contents himself with uncovering them. As he searches for hidden waterways and the source of the Earth’s magnetism, Walton is driven by the same noble aim of glory that initially inspired Frankenstein. Glory, not wealth, is his objective, and he is willing to sacrifice himself for the benefit of all humanity.

Studying at home as a child, Frankenstein had been inspired by reading sixteenth-century mystical chemists; like Walton, he was fired by starry-eyed visions of developing a universal panacea. At university, Frankenstein encountered two very different models of scientific investigator. The short and ugly Krempe, a parody of Enlightenment systematisers, ridiculed ancient knowledge and prescribed a rigorous modern reading list of texts in natural philosophy. Rather than striving for power and immortality, the cramped Krempe insisted on pinning nature down in the minutest detail and squeezing her into the confines of mathematical laws.

In contrast, Waldman was a far more sympathetic teacher. A charismatic chemist with a sweet voice and a sprinkling of distinguished grey hairs, he presented a progressive view of science. Frankenstein listened enthralled as he explained how modern chemists had inherited the alchemists’ dreams. Echoing Bacon and Davy, Waldman portrayed chemists as the miracle-makers of a new scientific age, who ‘penetrate into the recesses of nature, and shew how she works in her hiding places . . . They have acquired new and almost unlimited powers.’ Nevertheless, the dignified Waldman was governed by his intellect rather than his imagination. If you want to become a real man of science, he advised Frankenstein, then you must study not just chemistry, but all the scientific subjects, including mathematics.20

Unlike these two mundane teachers, Frankenstein is never physically described, as though he were pure mind, a restless enquiring soul existing on a different level. Born into a respectable orderly family, he is aware from childhood that he is destined for great things, and he ranks himself above ‘the herd of common projectors’. Like a Romantic poet, he is ‘a celestial spirit’ whose soul is elevated by contemplating the beauties of nature – an echo not just of Shelley’s husband Percy, but also of Davy, who wrote poetry as well as performing chemistry.21

So long as science and imagination are kept apart, Shelley’s fictional world remains an orderly place. Dangers arise only when the boundary melts, and imagination diffuses across into the scientific realm. Instead of behaving like a sober natural philosopher, Frankenstein lets himself be flipped over into dreams and fantasies. No longer a respectable man of science, he becomes a mad genius, governed by his internal creative fire as though he were a poet or an artist. Davy was London’s leading chemist, yet he also regarded himself as a genius – a creative investigator rather than a plodding natural philosopher. Science, he taught, was far more than a series of mechanical operations because it involved the higher planes of the human soul. By using scientific techniques and instruments, an inspired genius could be at one with the powers of nature and could uncover the secrets of life, thought and morality.

Walton the heroic explorer and Frankenstein the mad genius. Shelley contemplated the fluid character of contemporary science and crystallised out two heroic role models. Walton survives but fails, defeated by the strength of a female nature who refuses to let him approach the North Pole, source of the electrical and magnetic energy that activates the world. Frankenstein, far more presumptuous than Walton, aims not only to uncover nature’s secrets but also to control her powers – an over-ambitious project that is bound to fail.

In common with Shelley, modern female authors choose science fiction to express not only their reservations about science, but also their dissatisfaction with society. At the core of her book, Shelley used Frankenstein’s creature to expose the shortcomings of modern civilisation. ‘Some have a passion for reforming the world,’ she told her diary (she meant her parents and her husband). ‘I respect such,’ she went on, ‘but I am not for violent extremes, which duly bring on an injurious reaction.’ Rather than producing fierce political tracts like other members of her family, Shelley preferred the more enigmatic genre of fiction.22

Again, she drew on current scientific debates. Shelley’s journals show how avidly she read, novels as well as scholarly works on politics, philosophy, history. Perhaps she sometimes felt like the ‘Lady of Scientific Habits’ (Figure 30) – composed entirely of books and devoid of a body, this desexualised woman can give birth to nothing but more books. Was Frankenstein a substitute offspring, composed as it was while she was pregnant and haunted by the death of her first baby? In her book, Shelley explored the bond between the misshapen progeny and its arrogant creator. Viewing the world with a child-like naivety, the abandoned and nameless creature soon experiences the violence meted out to ugly outsiders. Like a magnifying mirror, his distorted image reflects the hierarchies of power that kept men at the centre and forced others – non-Europeans, women, labourers – to the margins.23

Like many of her readers, Shelley knew about Erasmus Darwin’s theory of evolution, his optimistic idea that species gradually improve by adapting to their surroundings over long periods of time. She was also familiar with Lawrence’s controversial suggestion that superior human beings could be produced – like agricultural animals – by selective breeding. During the eighteenth century, several so-called wild boys and girls had been discovered roaming the countryside, and the problems of educating and assimilating these children fuelled intense discussions in books and newspapers.

Shelley was familiar with the questions these children raised. Were they truly human, or had they deteriorated beyond recall? Were there fundamental differences between people and animals? And how should non-Europeans be classified – were they hopeless savages, or could they be brought up to Western levels? Linnaeus had even identified a distinct human species, homo ferus, a mute and hairy beast that shuffled on all fours. Like homo ferus, Shelley’s creature is prodigiously strong and can withstand extremes of temperature. Eavesdropping in the woodland cottage, he goes through a crash course in Western culture, and yet – like a feral child – he is never accepted by human society.24

Shelley was also interested in another type of classification – the differences between men and women. However trenchant her critique of men’s scientific aspirations, in many ways Shelley reiterated traditional attitudes towards women, nature and science. Even though her own life was far from conventional, she portrayed women as intrinsically fragile, home-loving creatures, governed by their emotions and their imagination rather than by rational thought. In contrast, her fictional men were active, outgoing, committed to academic study and capable of long feats of endurance. Shelley’s women conform to expectations by excelling in social skills rather than the rigorous intellectual work needed for scientific research – Elizabeth is the only one who can communicate with the servants.

As well as the myth of Prometheus, perhaps she was also thinking about Pandora’s birth, when the deities flocked round to teach her ‘every female Art’, and the muscular Minerva dwarfed the delicate Pandora (see Figure 3). Rather than imparting scholarly wisdom to Pandora, Minerva (Athene) consolidated female stereotypes by handing her protégée a shuttle to symbolise ‘the secrets of the Loom’.25 In Frankenstein, the two cousins Victor and Elizabeth are brought up together, but even as children they display characters dictated by convention. They are complementary partners – Victor is calm, dedicated and obstinate, the ideal counterbalance for Elizabeth’s docility, gayness and compassion. He is clearly destined for scientific research, whereas Elizabeth (like Shelley herself) thrives on art and literature. As Victor Frankenstein explains, ‘I delighted in investigating the facts relative to the actual world; she busied herself in following the aërial creations of the poets. The world was to me a secret, which I desired to discover; to her it was a vacancy, which she sought to people with imaginations of her own.’26

Female nature plays an important role in Frankenstein. Following tradition, Shelley personified nature as a woman with a dual personality (see Figure 11). Storms and flashes of lightning accompany episodes of evil, while the placid Swiss countryside restores Frankenstein to sanity. As children, Victor was calmer than his vivacious cousin, but as adults, Elizabeth’s serenity contrasts starkly with his feverish delusions and ravaged deterioration.

Condemned to live in domestic environments, Shelley’s women are doomed by their emotional self-sacrifice and devotion to duty. Frankenstein’s mother dies because, ignoring the cool voice of reason, she insists on nursing Elizabeth through scarlet fever. A serving girl confesses under duress and, with only a female advocate to plead her case, is executed for a crime she never committed. After years of faithful self-denial, Elizabeth is murdered because she obediently enters the bridal chamber alone. The major male characters, on the other hand, leave their homes to pursue active careers. Writing from the polar regions, Walton warns his home-bound sister that he may disappear for years – or even for ever. The close friends Frankenstein and Henry Clerval, in some ways Janus aspects of Percy Shelley, both abandon their families and devote themselves instead to study at a foreign university.27

Clerval, Frankenstein explains, ‘was no natural philosopher. His imagination was too vivid for the minutiæ of science.’ Even though obliged to opt for languages, as a man Clerval goes to university where he can work with scientific detachment and discipline. He chooses classical and oriental languages, which demand a good grasp of complex grammar and can be mastered by studying books. Like English, these are manly languages. Even the creature, eavesdropping on lessons inside the forest cottage, learns English more quickly than Safie, the family’s female pupil. Women were taught through conversation rather than books of grammar, and were being steered towards French, judged easy and slightly frivolous.28

Pandora and Eve were the traditional sources of sin. However, Shelley broke with convention by making a man rather than a woman responsible for the consequences of human presumption. The campaigner Mary Wollstonecraft, who was Shelley’s mother, had written, ‘Man has been held out as independent of His power who made him, or as a lawless planet darting from its orbit to steal the celestial fire of reason; and the vengeance of Heaven lurking in the subtile flame, like Pandora’s pent-up mischiefs, sufficiently punished his temerity, by introducing evil into the world.’29 Initially Frankenstein succeeds in usurping the female gift of procreation, but because of his audacity a new Reign of Terror is unleashed across the Earth – he has unclasped a Pandora’s box of evil consequences.

On the other hand, Shelley did not take the next step in role reversal. Although she seems to be condemning researchers who try to govern nature by ripping away her veil, in Shelley’s book science remains a pursuit for men. Nowhere does she suggest that science might fare better in the hands of women. For the first time, women were being given a scientific education, but they were still excluded from active research. As science started to move out of private homes, men like Davy mounted the public stage as science’s star performers. In contrast, his female readers, women like Marcet and Shelley, were restricted to vital but less visible tasks.

Like the women in her own novel, Shelley observed and commented, but did not participate in the manly world of science. A hundred years later, women would be working inside laboratories, studying at universities and demanding to be treated equally, but Shelley seems not to have contemplated this possibility. Like many radical writers, she remained snared in the conventions of her time. Mary Shelley conjured up visionary scenes of scientific horror, yet apparently she could not envisage such a drastic transformation of her own society.