You are the true Hiena’s, that allure us with the fairness of your skins; and when folly hath brought us within your reach, you leap upon us and devour us. You are the traiters to Wisdom; the impediment to Industry . . . the Fools Paradise, the Wisemans Plague, and the grand Error of Nature.

Walter Charleton, The Ephesian Matron, 1668

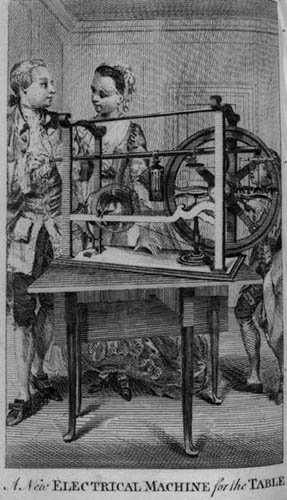

Idling away the hours at home, Euphrosyne longed for the vacations, when her brother Cleonicus came back from university. Then she could put aside her sewing and painting, and indulge herself in far more interesting activities – learning how to use telescopes, microscopes and air-pumps, or experimenting with the latest invention, electrical machines (Figure 18). ‘I often wish it did not look quite so masculine for a Woman to talk of Philosophy in Company,’ sighed Euphrosyne; ‘how happy will be the Age when the Ladies may modestly pretend to Knowledge, and appear learned without Singularity and Affectation!’1

Euphrosyne and Cleonicus were fictional characters, invented in the mid-eighteenth century by the lecturer Benjamin Martin to make his books on natural philosophy entertaining as well as instructive. An expert at marketing and self-promotion, Martin aimed his teaching at the growing number of young people – women as well as men – who were fascinated by new scientific ideas, but lacked the mathematics or the money to study them academically. Educational writers like Martin were keen to enlarge their audience (and their profits) by addressing women. There was no need to spell out the sub-text: if even women can grasp these scientific ideas, then any man should be able to understand them. ’2

Fig. 18 Euphrosyne learns about electricity. Benjamin Martin, The Young Gentlemen’s and Ladies Philosophy (2 vols, London, 1759–63).

The clever brother instructs his adoring younger sister. Cleonicus and Euphrosyne were updated versions of a familiar couple, the learned philosopher and the naive young pupil – traditionally, of course, a boy – who feeds his teacher all the appropriate questions. One of Martin’s rivals, a Fellow of the Royal Society called James Ferguson, taught astronomy to a wealthy young girl, an experience that inspired him to create another sister-brother pair, Neander and Eudosia. When Neander came back from Cambridge, Eudosia begged her brother to teach her astronomy, although she had a serious problem. ‘But shall I not be laughed at,’ she worried, ‘for attempting to learn what men say is fit only for men to know?’ Neander reassured her – and their readers – that any right-thinking man would encourage the many women who were eager to study science.3

Ferguson and Martin realised that there had long been many real-life sisters eager to study the new science, women like Anne Conway who begged her brother to keep her up-to-date with what he was learning at Cambridge. Conway was unusual because her work was published and her correspondence survives, but many other women must, like her, have borrowed their brothers’ books.

Catherine Wright, a diplomat’s wife from Plymouth, was one such sister who took advantage of her brother’s privileges. His tutor, she reported, ‘was a Man of Learning & fond of me, consequently gave me a taste for, & an Earnest desire after Studies not suitable to my Sex. What I learnt with him, Opend my Mind sufficiently to give me a pleasure in the Conversation of Men of Letters, & Books which I read at Stolen Hours.’ Isolated in Devon after her marriage, she experimented on local minerals and shellfish, and embarked on a scientific correspondence course with William Withering, a famous doctor. Saddled with time-consuming family duties and an ailing husband, Wright repeatedly worried about her own insufficiency and the inappropriateness of her studies. She begged Withering not to ‘expose my follies’ or think her vain: she knew only too well that ‘very few of our Sex Ever Attain to the Learning of a School Boy’.4

Withering’s female correspondents resented being excluded from academic studies. Wright wrote tartly that ‘the Generalty of men have Agreed that Women ought to be kept in perpetual Ignorance & the most profound Darkness’. Molly Knowles, wife of a fashionable London doctor, was still more outspoken: ‘Women to possess understandings of “masculine strength”, is an idea intolerable to most men bred up amongst each other in the proud confines of a College.’ Knowles sarcastically predicted a time when men would no longer monopolise learning: ‘as general education increases, Scholars will more & more discover to the confusion of their pride, that genius is shower’d down on heads, as seemeth to Heaven good, whether drest in caps of gauze or velvet – in large grey wiggs, or small silk bonnets.’5

Another real-life Euphrosyne was Elizabeth Tollet, who – like Anne Conway – complained bitterly about being left behind with only her books for company while her brothers went to university. Like Émilie du Châtelet, Tollet benefited from having an enlightened father who ensured that she was skilled in Newtonian mathematics and astronomy, as well as being learned in literature and the classics. To this studious girl, it seemed unfair that her younger brother Cooke should be at Cambridge while she remained trapped inside the walls of the Tower of London, where her father lived and worked. Convinced that the ‘gay and courtly’ Cooke would not take proper advantage of the educational opportunities she craved for herself, Elizabeth compared their fates:

All day I pensive sit, but not alone;

And have the best Companions when I’ve none:

I read Tully's Page, and wond’ring find

The heav’nly Doctrine of th’Immortal Mind . . .

Thrice happy you, in Learning’s other Seat!6

Iceberg tips of evidence are all that remain, but these snippets suggest that, contrary to the conventional picture, many women shared Tollet’s enjoyment of mathematics and natural philosophy during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. There are brief references to other individuals, such as the unnamed ten-year-old girl who astounded the Dublin Philosophical Society with her knowledge of ‘Algebra, Mechanicks, the Theory of Musick, and Chronology or the Calendar’. As well as enduring interrogations on astronomy and geography, she ‘was examin’d before ye Soc: in ye most difficult propositions of Euclid, wch, she demonstrated with wonderful readines’. When Polly Stevenson, the daughter of Benjamin Franklin’s landlady, begged him to teach her science, he sent her a book similar to Martin’s and, through letters, directed her studies for several years. Their correspondence covered a wide range of topics – barometers, tides, fireplace design. Then there are all the anonymous women who insisted that their favourite journal, The Ladies’ Diary, provide mathematical puzzles for them to solve. In response to female demand, the editor published more and more calculations and enigmas, many of them contributed by the readers themselves.7

What became of all these young women? A few of them confided their frustration to their diaries and notebooks, leaving behind tangible evidence of their learning and their interest in science. Some explicitly chose a strategy that would enable them to continue their scientific activities – they decided to live with men who were engaged in experimental research. Many more probably abandoned their earlier enthusiasm as they became submerged in the daily round of caring for children and husbands. But because experiments were being carried out at home, and not in a distant laboratory, even women with no previous scientific education inevitably became involved. Some of them were co-opted as technical assistants, others as editors, classifiers, translators or illustrators. All of them had to negotiate ways of accommodating research projects within a domestic environment, traditionally a female realm. Although only fleetingly acknowledged (if at all), these hidden women were involved in family experiments and affected the pattern of science’s history.

Concealed behind Euphrosyne’s electrical machine (Figure 18) stands a diminutive servant turning the handle. Scarcely mentioned in the text, John is one of those normally invisible assistants who was essential for making the machine work. As well as all the servile Johns who have been forgotten, experimenters also relied on their female relatives for help, although they often omitted to credit them for their essential labour. A few women managed to make their existence visible. Their stories must stand in for all those others that have been lost.