The Land of Pharaohs and Kings

British troops landed on Egyptian soil following the defeat of the French fleet at Abū Qīr Bay in 1798. At first their arrival was more or less accepted by the Egyptians until a nationalist officer named Colonel Arabi Pasha rose up and tried to force the British out. This courageous leader inspired the native masses, and in 1882 he roused the rebels into declaring war on the invaders. The British Cavalry galloped across the grey sands to meet the advancing rebels, whose artillery vomited angry jets of flames through the battle clouds. Shells screamed across the sky and tore open the ground around them. The British were falling from their saddles when the command came.

‘Charge those guns!’

The stirring Moonlight Charge that followed was commemorated in both paintings and verse. A trooper of the Second Life Guards told how the British Cavalry, eager to avenge their ill-fated comrades, stared death straight in the eye and cut their way through the screaming Egyptian hordes. Gravely wounded after his horse had bolted, Trooper Bennett staggered valiantly through the enemy lines, but the Bedouins lassoed him before he could return to his unit. With a rope around his neck, he was taken before Arabi Pasha himself, who looked down at the soldier with disdain.

‘The English are fools,’ he mocked. ‘I have 40,000 men at my command. Your feeble army will never return home; you will all be completely annihilated!’

Arabi Pasha (the Arabic word for ‘Lord’) had spoken too soon. The Egyptians lost hundreds of men that night and Britain was ultimately victorious. The rebels were routed in a dawn raid at Tel el-Kebir and the British entered Cairo the following month. Arabi Pasha was exiled from the land and the British ruled Egypt from then on as a protectorate.

By 1918 the Great War had come to an end, but instead of peace, unrest descended once again like one of the ten plagues of Egypt. An underground movement against the British began to stir. Scuffles broke out in Cairo and Alexandria, and a couple of prominent Egyptian radicals began to flex their muscles. Their names were Mustafa el-Nahas Pasha and Mahmoud Fahmi an-Nukrashi Pasha. Both of these university graduates began inciting the nation’s student population to go out into the streets and spill as much blood as they could. Under much pressure, the British decided to end the dominion, and in 1922 Egypt was granted its independence. An Anglo-Egyptian agreement was signed at St James’s Palace, and certain terms were reached, which could be briefly summarized as follows:

1. Egypt would be a completely independent country and was to retain its sovereignty. King Fuad was then on the throne, and his son, Prince Farouk, was his heir.

2. The defence of Egypt was to remain in the hands of Britain until the Egyptian Army had been trained to take over. A British Military Mission, commanded by a major general, would oversee the training of the Egyptian Armed Forces.

3. Once this was done, the British were to move out of Cairo and the Nile Delta to the barracks at Fâyid, close to the Bitter Lake of the Suez Canal, where they were to protect the Canal Zone.

4. The police, who were mostly Europeans and British, were also to be gradually withdrawn and replaced by Egyptians.

If Britain hoped that the signing of the treaty would placate the rebels then they were to be sorely disappointed. Though Egypt was outwardly gratified, behind the smiles was discontentment. There were still many citizens who craved the complete removal of the British Army from their land, and secret factions began plotting and scheming to rid Egypt of all British influence once and for all.

Mustafa el-Nahas Pasha was a conspicuous member of the political Wafd Party, a nationalist party whose name meant ‘for the people’. His liberalist views afforded him great standing among the poorer classes – of which there were many – during the 1930s. The starving masses idolized him, and in consequence he wielded great power over the land of Egypt. He did more than anybody to help improve the lives of the poor fellaheen (peasant labourers), and I witnessed much of his good work for myself.

Because of this man’s unprecedented popularity, King Fuad and Prince Farouk greatly distrusted Nahas Pasha. When the king died in 1936, and his teenage son ascended the throne, a great rivalry between Nahas Pasha, of humble descent, and the blue-blooded Farouk was born. If Nahas could have had his way, Egypt’s sovereignty would have died with the late king. How he longed to remove the prosperous young ruler from the throne and divide his riches among the people. He would have done so in a heartbeat, given half the chance, but in those days the king was backed by the powerful British, and was effectively untouchable.

Major General Aziz el-Masri Pasha was an impeccable and ambitious officer of the Egyptian Army who, like Nahas Pasha, despised British supremacy with a passion. During the First World War he’d made no secret of the fact that he was staunchly pro-German, and had been actively engaged in street riots and political revolts. For this reason tensions between him and the authorities were high.

Their mutual determination to oust Britain from Egypt united Masri and Nahas Pashas, and together they recruited a band of likeminded militant renegades. Hassan al-Banna was the fanatical head of the recently formed Muslim Brotherhood; and the debonair Lieutenant Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser, a popular man with almost everybody he came into contact with, had begun concocting radical plans of his own. Outwardly he was shy and retiring, but behind his deep brown eyes was an ambitious and determined soul.

By the time we arrived in Egypt in 1937, the revolutionary mobs were growing restless and street riots across the major cities were becoming frequent. Political activists were once again whispering into the ears of impressionable students, filling their minds with all sorts of anti-authoritarian notions. It wasn’t difficult to brainwash some of these young people, who found street skirmishes more interesting than their studies. We all knew Nahas Pasha was responsible for winding up this army of toy soldiers and letting them go, but proving it, and thereby getting to the root of the problem, was another matter entirely.

I had a cousin back in Dublin who worked as a theatrical agent at the Gaiety Theatre, and he often travelled the world in search of new stage talent. He’d once described the docks at Alexandria as the ‘backside of the world’. I never understood what he meant until HMT Dunera docked, and I realized just how right he was. Everything was untidy and haphazard. On one side of the docks, dozens of barefoot labourers in filthy rags unloaded bale upon bale of merchandise. A wily master who had the run of the docks hired out these gangs and made a fortune from their toils, whilst the workers themselves received a pittance. They were made to run here, there and everywhere under the supervision of a man armed with a rhino whip, which he used unsparingly.

Yet despite the abject poverty that afflicted this land, the average man on the street acknowledged we Britons as friends. As we made our way along the docks, we were patted on our backs and greeted with warm words of welcome.

‘Hello, Johnny!’ they’d cheer, flashing us glimpses of decaying teeth. This was usually followed by the word ‘Buckshees’, which meant ‘tip me’, as they held out their open palms with expectant expressions.

Swarms of barefoot urchins were running around beside us, dodging in and out of our legs. Their faces were dirty and they had the strangest of remarks on their lips.

‘I come from Mobarak, where Husani lives.’

‘Do you know Fatimah from Manchester?’

We were surprised at their knowledge of English and of England, forgetting that for nearly six decades troops had been doing just as we were, coming into Egypt from Great Britain.

As we drew up in a straight line beside the tram stop, we saw the most peculiar-looking electric tram pulling in. It was small and made entirely of wood, and reminded me of the old Dublin steam trams from long ago. The conductors and drivers were dressed in ill-fitting suits of khaki and each wore a red fez on their heads. All aboard, and with a sharp toot on the funny hooters, off we set in these swaying, wooden vehicles. Pungent smells drifted in through the open windows, and we gazed outside as the derelict scenery passed us by. Through the flies and the dust we could see that the dock neighbourhood wasn’t at all pleasant. This was a place where you could have your throat cut for a farthing and your body whisked away for a halfpenny, never to be seen again. This was the place where holy men rubbed shoulders with murderers, smugglers, robbers and dope fiends, and where the prostitutes plied their trade from behind bars like caged animals.

Leaving this bleak part of the world behind us, we entered Alexandria’s European quarter. In stark contrast, this district was filled with cinemas, sports grounds and well-kept properties on delightful avenues banked with flowers and palm trees.

After some 4 or 5 miles the tram stopped at a place called Sidi Gaber. Spread out on the other side of the road stood Mustapha Barracks, the great military fortress that was to be our home for the foreseeable future. We marched through the gate behind the Corps of Drums and it soon became apparent what a sprawling place Mustapha was; yet despite its enormity this was not the only army base in the city. The Royal Egyptian Navy was also stationed here, and theirs was one of the biggest bases in the Middle East. Unfortunately for them, the navy was the butt of many Egyptian jokes, as their annual naval manoeuvres consisted of moving from one part of the harbour to the other. On one occasion, one of their destroyers was sent out to sea with the purpose of finding Malta. Some few days later it returned, much sooner than expected.

‘Malta mafeesh,’ the admiral reported, which meant: ‘there’s no such place as Malta: I couldn’t find it.’

Mustapha Barracks was just a short walk from the beautiful blue waters of the Mediterranean, and we were all rather disappointed to learn we were to be confined to barracks for the first two days of our stay. However, this proved to be a wise move, as our commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel J.A.C. Whittaker, had decided to bring in a man with local knowledge to put us in the picture about life in Alexandria before allowing us to wander about in this strange land unprepared. Egypt was very different from Palestine, and was becoming more dangerous by the day. Riots and violence were a part of daily life, and Alexandria was infiltrated with spies. We were told they could be anyone. They could be blonde or they could be brunette, and we had to learn quickly to trust no one.

Lectures over, and with a disharmony of guidelines ringing in our ears, we were allowed to explore Alexandria in our free time. I soon began to discover the customs, places, and the dos and don’ts of Egypt for myself. Despite all the warnings, I was pleasantly surprised by the ease with which one could make friends with the average man on the street. The local shopkeepers were particularly amiable, and I once asked one of them what the strange, exotic smell of the East was.

‘Have you ever seen a public urinal in Egypt?’ he asked me.

‘Erm, no,’ I replied. ‘I don’t believe I have.’

‘Well, there you have it, boy,’ he said. ‘They have to do it in the streets here, and the smell remains forever.’

The lack of good sanitation wasn’t the only regressive thing about this country. For many decades the brave women of the suffrage movement had been fighting for equality in the West, and in recent years had made considerable progress in battering down the boundary between the sexes. In the East, however, women were still the inferior gender, and it wasn’t wise for a local girl to be seen in the company of a man who wasn’t her father, husband or brother. Matters were made significantly worse if the suitor in question happened to be a British soldier.

One day I met a lovely young lady and rather foolishly asked her out for a date.

‘That would be nice,’ she replied cautiously, ‘but you must wear civilian clothes. And, of course, my mother, my four sisters and two of my cousins will be coming along as chaperones.’

This appeared to me to be some sort of racket to get the whole family a free treat, and I was having none of it, so I remained dateless.

Though I’d learned that the women of Egypt were strictly off limits, the menfolk were an approachable bunch who were possessed of many pipe dreams that never seemed to become reality. After lunch they used to lie in the sun until teatime and dream of the three things they yearned for the most: a gun, a horse and a wife, usually in that order. Their fourth wish was a regular supply of hashish. This was an illegal drug that everybody seemed to crave. It wasn’t unlike cow manure in appearance, and was always carried in the top left-hand pocket of one’s jelabiya – the white garment that the men wore, which looked a little like a nightshirt. There were only two classes of Egyptians in those days: the very rich and the very poor, and the very poor relied on the sale of this drug to earn an extra penny.

The British Army in Egypt was one of the country’s major employers of working-class Egyptian men. At the barracks each company had a man known as a dhobi, who was responsible for washing the laundry and other such activities. These employees had begun work as children, alongside their fathers, and after the fathers had died, the sons had taken over. Dhobies were always spotlessly clean and could be seen dashing around the barracks in the whitest starched clothes with a bright red fez stuck jauntily on their heads. Our dhobi was known as Ali Cream, and he was a sharp character indeed. For five piastres (about one shilling), he’d take away a kit bag full of washing in the morning before we got up, and it’d be back before sunset, clean, starched and ironed.

No parade took place after 10.00 am in the morning, and when we weren’t on patrol duties we were free to do as we pleased for the rest of the day. A taxi ride from the barracks to the centre of town cost less than a shilling; a large glass of Stella beer with plates of food to go with it cost no more than a shilling, and a good seat in the cinema cost pennies. What more could a chap ask for?

Along the coastline one could find lovely beaches with gaily painted sunshades, bathing cabins and sun-bronzed bathers, but it was the crowded streets of Alexandria that interested me the most. Here one could see every class and race of person going about their business in one united community. It was said that there were more than 20,000 Italians here; and with the Greeks, Syrians, Armenians, French, British and others, one could really appreciate that Alexandria was a truly cosmopolitan city.

On an evening the city was ablaze with lights, and the crowds were buzzing. There were plenty of places that offered entertainment, though some venues were strictly out of bounds to the common soldier, or, as the French called us, ‘the other ranks’. This seemed unfair, but I later discovered one or two fairly decent establishments that were open, and I was more than contented with my lot in life.

Having settled into a new regime in this foreign land, I received an unexpected telephone call from a Mr Jack Davy who worked in Alexandria for Barclay’s Bank. He was a civilian who’d given up much of his free time to look after the interests of a harmonica band formed by the 2nd Battalion of the Grenadier Guards, who’d been stationed in Alexandria up until our arrival. Jack had arranged concerts for them in venues across the city, and word had reached him about my band. Keen to continue his role as booking agent, he invited me to call to see him at his house in the hope of reaching a similar arrangement. This was the first time an English resident had asked me to visit his home, and I was made most welcome by this kind gentleman. His wife served us tea and cake on the veranda, and I felt like an honoured guest when she brought out their best china cups and saucers.

‘I’ve heard great things about your harmonica band, corporal,’ Jack said with a smile. ‘As I understand it, you’ve been performing for the troops and you’ve gone down very well indeed.’

‘Well, we’ve certainly been performing our hearts out,’ I replied, suspecting that whoever Jack had been speaking to must have exaggerated our success. ‘But we’ve been doing it out of enjoyment more than anything else. None of us are professional musicians. We just want to go out there and have a good time, and hopefully entertain our chums in the process.’

Jack placed his cup on the coffee table and sat forward in his chair. ‘How would you feel about performing to a wider audience?’ he asked.

A wider audience? I liked the sound of that, but surely nobody outside our circle of friends and comrades would be interested in hearing us play.

‘My senior executives at the bank have asked me to find an act to perform at our staff Christmas Eve ball,’ he explained, ‘which is to take place at Nouza Casino. I rather hope that you and your band will be interested in this opportunity.’

I could hardly believe what I was hearing. Our first proper engagement!

‘Yes, indeed, we’d be honoured,’ I said, grinning like a Cheshire cat. ‘If you really think we’re what you’re looking for.’

Jack assured me we’d fit the bill perfectly, and I left his house feeling awash with excitement. An official commitment for my little band, and for the bigwigs of Barclay’s Bank, no less! The Nouza Casino was one of the most prestigious places in town, and my band mates were staggered when I told them the news.

Dressed in our white silk shirts and matching cricket trousers with red cummerbunds around our waists, we duly arrived at the agreed time on Christmas Eve. The casino was decked with all the usual festive trimmings, and we were so taken aback by the elegance of this palatial venue that we tiptoed inside, feeling completely out of place. We took drinks at the bar and fretted about the standard of competition we’d have from the resident band that was to play alongside us. We didn’t have long to worry, for beautiful music, performed with utter balance and perfection, soon began drifting through the room. To our dismay the members of this band were exceptionally talented, and we knew even in our wildest dreams we couldn’t compete to that standard.

With knees a-trembling we left a long line of empty glasses on the bar and prepared to take centre stage. It was only then we discovered, to our relief, that we’d spent the past few minutes fretting over a recording of a world famous band that was being broadcast over the wireless. The real resident band, it transpired, was pretty mediocre. Things went better than expected, and at about 11.00 pm the guests sent the resident band packing and we held the floor until early in the morning.

After Christmas we became inundated with engagement requests, and the Merrymakers’ Harmonica Band became quite famous locally. One day our guitarist, Jimmy Norton, and I were invited to the Summer Palace for a chat and drinks with the proprietor, who wanted to hire us. This was a popular – not to mention expensive – hotel and resort within an exclusive residential area of Alexandria called Zizinia. I only had twenty piastres (about four shillings) to my name and Jimmy was completely broke, so we tried our best to get out of the invitation, but to no avail.

Alexandria, Egypt, 1937: the Merrymakers’ Harmonica Band on stage, with Paddy (centre) on the drums.

‘Hold on to your hat,’ I whispered to Jim as we stepped inside. ‘It’ll cost you an arm and a leg to get it back!’

Unfortunately, however, the well-rehearsed concierge was too quick for us and Jim’s hat was whisked from his grasp before we’d even crossed the threshold. Like a man possessed I dashed after it and managed to return it safely to its owner without paying a penny.

As Jimmy and I approached the bar, I prayed the owner drank beer so at least we’d be safe for one round. Albert Metzar, who was reputed to be a millionaire, was already waiting for us. My heart sank as soon as I laid eyes on him. This chap looked so refined I thought a double whiskey would be the least he’d want. Thankfully for us, he bought the first round, and Jim and I were careful to take a long time to sip our Stella.

Mr Metzar was a charming man, and he offered my band a top engagement to play at his hotel as part of a lavish show that was being planned to mark Bastille Day.

‘His Majesty King Farouk will be in attendance,’ Mr Metzar enthused. ‘I’ll even present you to him during the evening.’

Naturally, we were thrilled, and I hit on the idea of getting the band to play the first eight bars of the Egyptian National Anthem as the young monarch arrived. This we did, and during a break in the proceedings the king actually came over and chatted to us. He was a rather plump fellow with a perfectly coiffed moustache, and though he’d crossed the threshold into adulthood he still retained all his boyish charms. I was instantly drawn to his attire, which was so immaculate that even our sergeant major wouldn’t have found fault. His Majesty even appeared to have at least three or four pocket watch chains protruding from his waistcoat, though what he needed so many for, we didn’t enquire. It was well known that Farouk was no fan of the British, but he was pleasant in his conversation and seemed to enjoy our show.

One of the main attractions at the festival was an exceptionally beautiful Egyptian belly dancer, and what a showstopper she was. Following her act was a slightly less alluring Australian chap called Sweeney, who, dressed as an Egyptian lovely, wiggled and danced to the delight of everyone, including the king.

Alexandria, circa 1940: a portrait of Paddy with his good friends, Yvonne and Layla Shakour.

During the evening I met a charming family who lived nearby. The two sisters were Yvonne and Layla Shakour, and their older brother was Joseph, who I learned was a friend of the proprietor. They showed great interest in our performance and invited me to join them for drinks and a bite to eat at their table. The four of us spent a most enjoyable evening together, sharing small talk and witty anecdotes, and I found my new companions a pleasant bunch indeed. At the end of the night they suggested I should take tea with their family one day. I agreed with pleasure, and the following weekend arrived at their exclusive address in Zizinia.

Their Swiss-type chalet was tucked away behind a thicket of palm trees, and from the veranda you could look down onto the golden stretch of sand beside the sea. It was a beautiful neighbourhood, and my three friends introduced me to their aunt, Vanda, and their uncle, Charles Shakour Pasha. He was an Egyptian-born Syrian gentleman who, having been educated at a public school in England, had a deep respect for Britain and our Western culture. I was entertained most kindly that afternoon, and soon became a regular visitor. Over time the Shakours welcomed me into the bosom of their family, and the six of us remained lifelong friends.

It was 1938 and the unwelcome news reached us that further troubles were brewing in Palestine. This didn’t concern us, though, for we were on our way to a training exercise at Fâyid, a desolate place in the Egyptian desert beside the Great Bitter Lake. We boarded the primitive cattle trucks that graced the railways in those days and departed Alexandria, passing through Tel el-Kebir, where the British had first defeated the rebels. After a bone-shaking journey we stopped in the middle of the desert at Fâyid Station and marched the remaining few miles to our tent camp at the foot of Little Flea and Big Flea. These were two huge mountains of sand, where we were to call home. Just a few miles away lay the grey-coloured waters where trade ships from every nation waited to pass through the Suez Canal.

We spent about three weeks at this godforsaken spot, marching by day and firing our weapons by night, all the time enduring incessant sand storms, until the warning came to stand by for orders to proceed to the Holy Land on active service. This came as no surprise. It seemed as if the world was going to pieces again. In 1935 the Italian prime minister, Benito Mussolini, had declared war on Abyssinia, and less than a year later Hitler had violated the Treaty of Versailles by ordering his troops into the Rhineland. The German Führer was putting into action his plan to annex Austria, and all in all things were looking pretty bleak, to put it mildly.

Egypt, circa 1938: Paddy in the desert.

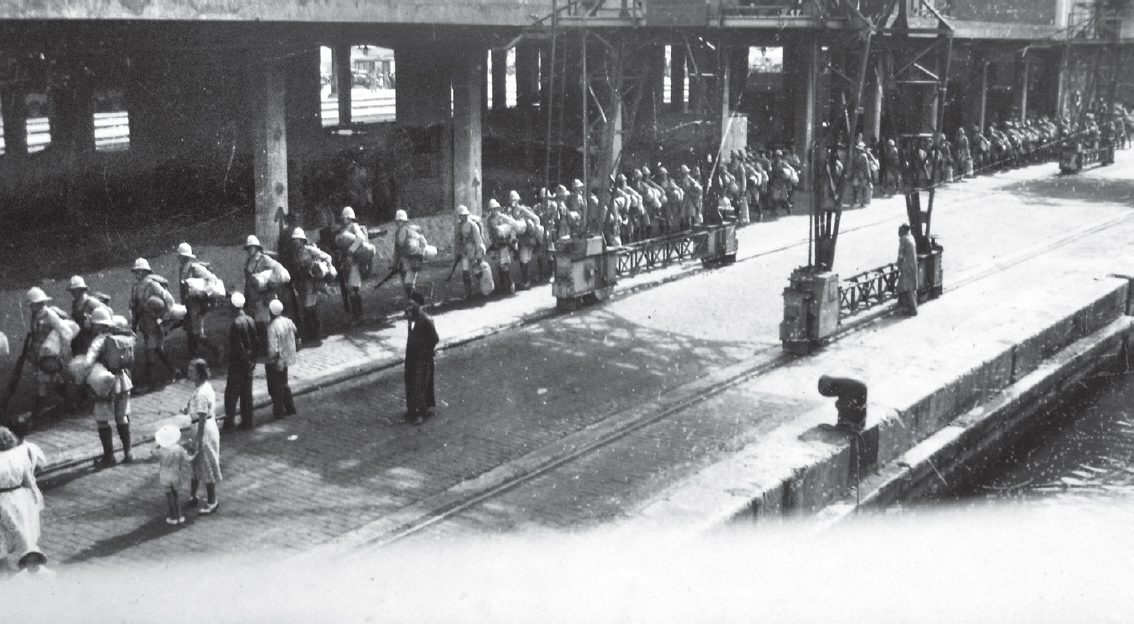

Alexandria, 1938: the 3rd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards arriving at the docks, about to set sail for Palestine.

On 14 October 1938 we sailed away from Egypt in the direction of Haifa, and could hear the crackling of gunfire and thumps of exploding landmines before we’d even entered the docks. It appeared that the Arabs had become quite the experts with these weapons since our last visit, though that was hardly unexpected, as they’d had plenty of practice.

Alexandria Docks, 1938: the 3rd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards embarking the ship for Palestine.

Alexandria Docks, 1938: Paddy (marked) and his comrades setting sail for Palestine.

Jerusalem, 1938: two rebels preparing for trouble.

We moved to Jerusalem by night and were told we were to enter the Old City at dawn. Enemy moles were all around us: they were employed in the canteens, the local tailors’ shops and even as dhobies, so we troopers were never given the full picture of what lay ahead. We were simply informed that an armed band of rebels had captured the walled city, killing and plundering as they did so. They numbered approximately 500, and our duty was to get them out, either alive as our prisoners, or dead.

In those soundless moments before the sun had risen we slipped through the deserted streets of Jerusalem wearing canvas shoes instead of nailed boots to remain unheard. The early morning mist was tainted with the scent of gunpowder from yesterday’s battle, yet the air was still. Not a single noise could be perceived save for an occasional cock crow. I felt jittery as I climbed over the gate and took up my position with the others on a high wall directly overlooking the Mosque of Omar, but we’d been warned that only in extreme circumstances were we to open fire on that holy area.

As the grey streaks of dawn appeared, the low rumble of our approaching aircraft stirred the concealed rebels into action, and all hell broke loose. Rifle and Bren fire thundered all around us, along with the thumps of grenades and the rebels’ homemade bombs. I had a clear view from where I was positioned, and could see dozens of figures in black running for cover. Coming up from the narrow streets below were two Guardsmen carrying one of our comrades between them. Bright red blood was streaming from his otherwise ashen face. A grenade had been lobbed at him from the window of a nearby house.

Jerusalem, 1938: the Guards mining a rebel stronghold.

I received orders to move my section up to the Damascus Gate. In single file, and with rifles at the ready, we made our way swiftly along the cobblestones. Several dead bodies littered the streets and terrified civilian faces peered furtively from behind their windows. As soon as we arrived at the gate I was ordered to sight my Bren gun across to the Old City from a high wall; my riflemen were to be deployed in and around the gate area. I was told I was to control all movement in and out of the city, and wire cages were erected in order to detain our Arab prisoners.

I stood on guard at my post and watched with bated breath. Every few minutes flares and explosions would illuminate the dawning skies and bullets flew across the horizon like shooting stars. When the gunfire ceased, a deathly silence fell over the city; then everything started all over again.

A band of the most fearsome rebel snipers soon began to make things heated for us. From a minaret approximately 350 yards from my post, a sniper was having a lot of fun shooting across the way whenever a target presented itself. We had orders to leave him alone for a while as this was a holy spot, but his audacity made our blood boil. He’d come into view for a second to take a well-aimed shot before darting back into his hiding place like the slithering coward he was, before repeating the process. Patience has its limits, and a sudden burst from Guardsman Patfield’s Bren shook the dust from the minaret. The sniper was unharmed, and he fired back with a renewed fury. That was when Patfield’s gun fell silent. He slumped forward, a bullet having passed right through his neck. As he dropped dead on the windowsill where he’d been positioned, every weapon in the city opened fire.

Palestine, 1938: Fawzi Bey with his rebel troops.

The scene of desolation all around me was a far cry from the picture of peace I’d had in my mind whenever imagining the Holy City. There was nothing but death and hatred in this place; and as twilight fell I stood back while the blood-soaked corpses of rebels and Guardsmen were stretchered away out of the Damascus Gate.

The guns had fallen silent by now and my chaps were naturally subdued, so to cheer them up I sent Guardsman Jock Hamilton to a furniture store that had been broken into during the riots, and asked him to retrieve some mattresses and blankets for the men. It was cold where we were, but with the extra bedding we were able to settle down for the night in relative comfort.

An explosion in Palestine, 1938.

The Royal Air Force flew over Jerusalem before first light, dropping leaflets that warned people to stay in their homes while we conducted our searches for arms and rebels. If anybody was caught venturing outside, they’d be shot at.

At daybreak the Palestine Police Force began to march out their prisoners in chains, and a scurvy looking crew they were, dressed in oddments of rags, and many in bare feet.

‘Don’t feel sorry for them,’ one of the police inspectors said to me. ‘They’d slit your throat, given the chance.’

I was detailed to take a message to a party of sappers who were positioned near the Wailing Wall. I took two of my men along with me, and as we raced along the streets, we came upon a party of curfew breakers. Most of them were children who refused to budge to let us through, and were defying us to shoot them. I didn’t have time for this, so I grabbed one of the youngsters by the scruff of his neck, threw him over my knee and administered a few hearty smacks. In a thrice the streets were cleared.

We delivered the message; and on our way back, as we passed by the area known as ‘the Way of the Cross’, a local lady beckoned me to her door.

‘May I be allowed permission to take my ox to water?’ she enquired.

‘I’m sorry but there’s a curfew on,’ I explained. ‘Orders are nobody’s permitted to leave their homes until we’ve conducted a thorough search of the city. Where exactly is your ox?’

‘Right here,’ she replied, as if the answer was obvious.

I peered round her door and was shocked to see the family’s ox faithfully observing the curfew in the living room. I also noticed there were three grown men in residence, hiding behind the petticoats and leaving the woman to do the asking. I passed on her request to the police inspector and I’m glad to say permission was granted.

Information was received on our third day of our being in Jerusalem that people were to be allowed to come out of their homes from 10.00 am until 5.00 pm, and I was given orders to search every single person who passed through the Damascus Gate. There must have been thousands of people living in the city, and I felt myself beginning to perspire just thinking about it. Nevertheless, orders were orders, and I duly waited in my position for the curfew gun to fire.

BANG!

And then they came. On foot, on donkey, on camel, in pushcarts and the devil knows what else. Holy men, beggars, the blind, rich merchants, women and children alike all surged towards me as one. The exodus lasted hours, and except for the odd wicked-looking knife, a supply of hashish or one or two packets of cocaine that I handed over to the police, nothing of importance was discovered. Thankfully, after a week or so of this rigmarole, order was restored and the police resumed their normal duties.

Jerusalem, 1938: a snap of the Old City taken by Paddy while he was Guard Commander of the Damascus Gate.

Some 2,000 miles across the sea, Germany was growing stronger by the day. The Nazis were secretly developing their formidable Luftwaffe, and though the world knew exactly what Hitler was up to, nobody was brave enough to stop him. Unchallenged, his army invaded Czechoslovakia, and Poland was next. The mighty Adolf Hitler was standing four-square in Germany, with profitable and industrial lands in his pocket, ogling at the rest of Europe with greedy eyes. He thought the world was his for the taking.

So, here we were in 1938, on the brink of another world war. In two short decades our enemy had returned to the arena fighting fit. Germany was ready to go again. The question was: were we?