PUBLIC POSTERS WERE a significant part of police methods of appealing for information, with considerable rewards regularly being offered from government funds. The earliest such reward poster, issued by the Metropolitan Police in 1829, related to a man known as John Berrigg who was wanted for horse theft, whilst that issued for Charlie Peace in 1876 was an early example of a poster containing an illustration of the wanted man.

What became known as the Burton Crescent Murder was discovered on Sunday, 9 March 1884 when a young woman, Mary Anne (or Annie) Yates, was found dead in her lodgings at No. 12 Burton Crescent, near Euston, by her friend Annie Ellis, who also lodged in the house. Annie Yates had a wound to her head caused by a blunt instrument, bruising on her chest, and injuries consistent with being strangled to death. In the general untidiness of her room, a half sovereign was found amongst her bedclothes. Annie was an ‘unfortunate’ (or prostitute), who had a paralysed right arm. She had originally come from Reading and her real name was Mary Anne Marshall. On the previous evening Annie Ellis had walked out with Annie Yates, but had parted company from her at about 1.15 a.m. when Yates had gone to speak to a man on the corner of Euston Road and Tottenham Court Road before heading off with him towards Burton Crescent. The street door of the house had been banged shut with some violence at about 4 a.m. after some ‘hysterics’ or ‘screaming’ had been heard.

The landlady, Mrs Eliza Evans of Lewisham, told the inquest that she had rented the room to Yates on the basis that she was a married woman accompanied by her husband, and that a Mrs Sarah Apex acted as a caretaker for the premises. Evans owned two other houses and the coroner was distinctly unimpressed when she claimed not to know whether her tenants in those houses were also prostitutes. Yates’ background was a sad one: she had been found abandoned as a 5 year old in Regent Street by a police officer from Great Marlborough Street. Detective Sergeant James Scandett told the inquest that she had been sent to Westminster Workhouse, then to St James’s Industrial School in Tooting, was put into domestic service but then ‘fell into evil ways and lived an immoral life’. The inquiries to trace the man who had been with Yates that night were unsuccessful, and the case remained unsolved.

It was a reflection of the tragic circumstances of young women who fell into prostitution, but the posters did result in a number of people coming forward in unsuccessful attempts to identify her as a missing relative. The inquest ended with the coroner taking note of a deputation of local residents who pointed out that their neighbourhood was largely a respectable one, that houses of prostitution such as No. 12 Burton Crescent should be prosecuted, and that they wished the name of their street to be changed. Burton Crescent had been built around 1810 by James Burton and named after its builder; it became Cartwright Gardens, after the political reformer Major John Cartwright who had lived at No. 37.

![]()

The murders of prostitutes have often caused problems for the police because of the difficulty in identifying their clients. Twelve years earlier, another notable case had occurred where the police caused controversy by pursuing inquiries into the clients of Harriet Buswell, another ‘unfortunate’. The comments in newspapers of the time blamed the police for arresting the wrong person, but also expressed outrage at the prospect of a gentleman ever being accused of such a crime. The idea of the police investigating into a prostitute’s clients was seen as abhorrent.

On Christmas morning 1872, Harriet Buswell, like Annie Yates, was found murdered in her lodgings. For many years a plaster cast of a half-eaten apple was stored in the museum in the hope that it might provide the means of confirming or disproving the identity of a future suspect by comparing details of his bite marks.

Late on the morning of 25 December 1872, the occupants of No. 12 Great Coram Street became concerned that they had not yet seen 27-year-old Harriet Buswell, who lodged at the address. They opened her room and found that she had been brutally murdered. There was a bloodstained thumbprint on her forehead and other bloodstains in the room, but the modern techniques of crime scene investigation – blood grouping and fingerprint analysis – had not yet been developed. The body was taken to St Giles Workhouse where the recent development of photography was utilised in order to assist in the issue of identification. Harriet Buswell was also known as Clara Burton, and had a daughter who had been fostered out to a neighbour for 5s per week. Buswell lived in poverty, relying on her activities as a prostitute to get by. Her situation was in one sense summarised by the discovery of a pawn ticket for five pairs of ladies’ drawers. She had borrowed 1s from a fellow lodger the previous evening and had returned at about midnight with nuts, oranges, apples and enough money to be able to pay her landlady half a sovereign. She had brought a man home with her who had been heard leaving the house at about 6.30 a.m. on Christmas morning.

Superintendent James Thomson from E Division took charge of the investigation rather than an officer from Scotland Yard, but whether this was significant is difficult to judge. The Detective Branch was in the last five years of its existence before the introduction of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), and had been under great pressure, not least from investigations into the Irish Republican Brotherhood and their 1867 Clerkenwell explosion. Harriet Buswell’s movements from the Alhambra theatre were traced. Various witnesses had seen her with a foreign man, possibly German, who had a swarthy complexion and blotches or pimples on his face. A reward, this time for £200, was offered for information.

The reward posters appeared to pay dividends when a development came from Ramsgate, where the local police suspected a man, Carl Wohlebbe, the assistant surgeon of German brig Wangerland that had been put into the port at Christmas for repairs. Superintendent Thomson sent Inspector Harnett down to Ramsgate with George Fleck, the greengrocer who had served Harriet Buswell her nuts and oranges, and a Mr Stalker, a waiter from the Alhambra who had served Harriet and her companion with drinks on Christmas Eve. Carl Wohlebbe was placed on an identification parade of about twenty members of the ship’s crew, but both witnesses stated that Wohlebbe was not the man that they had seen. Amongst the other members of the crew making up the parade was Dr Gottfried Hessel, the ship’s chaplain. Both witnesses positively identified him, rather than Carl Wohlebbe, as the man that they had seen with Harriet Buswell. Both Wohlebbe and Hessel had in fact been in London that night. Hessel was duly arrested and charged with murder.

On 20 January 1873, Hessel appeared at Bow Street magistrates’ court and was remanded. Sir Richard Mayne had died three years earlier and murder cases no longer had the supervision of a barrister-trained commissioner. Mayne’s successor, Colonel Henderson, was a military man. The police sought legal assistance from a firm of solicitors to conduct the case, an early form of the role later played by the Solicitor’s Department at Scotland Yard, the Director of Public Prosecutions and the Crown Prosecution Service. A week later, two further witnesses identified Hessel in the Bow Street dock as having accompanied Harriet Buswell that night, but others expressed doubts. A housemaid from the Royal Hotel in Ramsgate testified that Hessel had asked for turpentine and a clothes brush when he had returned from London, and one of his handkerchiefs had been saturated with blood. Hessel gave alibi evidence that he had never left his London hotel that night because of illness, and this was supported by Carl Wohlebbe, but there is no record of this alibi being investigated by the police. It is possible that the prosecution simply decided not to call evidence that they knew would not support the case against Hessel, or that the advocate summarised such evidence to the court.

The magistrate, Mr Vaughan, discharged Hessel and declared that he was being released without suspicion attached to him. Hessel was cheered by crowds and a public subscription was raised for him by the Daily Telegraph before he continued his voyage to Brazil. The money may have been more welcome than anticipated: an anonymous letter received after his acquittal outlined a catalogue of spendthrift conduct, drunkenness and debts left behind by Hessel in Germany. The case reflected the speed with which suspects were charged in those days; nowadays there would be a much more thorough investigation before commitment to a prosecution. It was also an example of how identification parades could have unintended consequences. A modern investigator would have checked whether any of Hessel’s fingerprints matched the mark on the victim’s forehead and would have checked his teeth. Analysis of the bloodstains, not least on Hessel’s handkerchief and, perhaps, on his clothing and at his hotel rooms, would be likely to have confirmed or disproved his involvement.

The Commissioner’s Annual Report for the year referred to the case and stated: ‘It was held at the time that the Metropolitan Police, to whose custody the person charged was committed, were to blame in the matter; but, in fact, they had no alternative whatever, and acted throughout strictly in accordance with their duty.’

1888

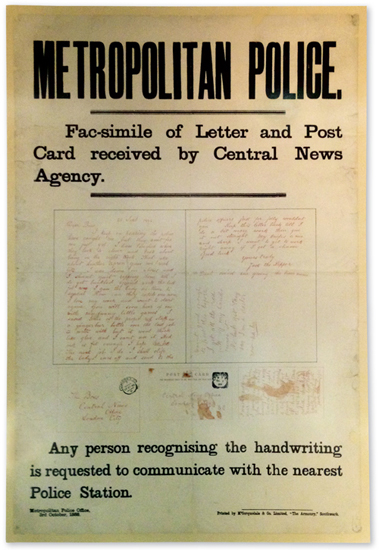

Appeal poster publicising the handwriting of Jack the Ripper