THE CCTV IMAGES from cameras located in various parts of London have often been crucial in providing images that help identify offenders. In this case it was a series of nail bombs that exploded over the course of three weekends in London in April 1999. The first detonated on a Saturday at 5.30 p.m. in Electric Avenue, a busy market street in Brixton. The police had been notified of a suspicious cardboard box with a plastic container on top and a clock in it. Another member of the public described a sports bag with a box of nails and batteries. The bag was stolen by a thief, who had apparently not realised the danger he was in. The timing device had not been triggered at this point, but the bomb did explode shortly afterwards. The thief was injured, along with thirty-eight other people, which included the three police officers who responded to the call. The explosive had apparently been removed from fireworks, and various pieces of small cog wheels indicated that a clockwork timing mechanism had been used.

1999

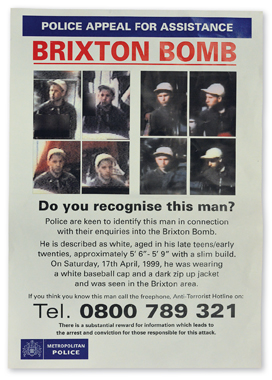

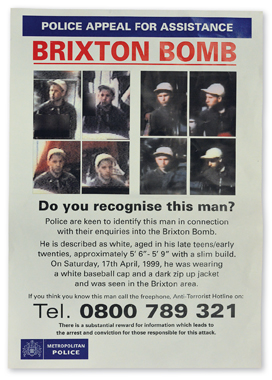

CCTV images that helped to identify David Copeland

The second explosion occurred shortly before 6 p.m. on the following Saturday, 24 April 1999, in the East End’s Brick Lane, also an area with many ethnic minority residents. The owner of a Ford Sierra estate had returned to his vehicle after he had found the restaurant he intended to visit closed. Finding a sports holdall with a box inside it by his car, the man picked it up to take to the nearby police office, which was also closed, and then put it into the back of his car. When the car owner had walked 100yds away, the bomb exploded. He became the second man to have unwittingly picked up a sports bag that had been about to explode!

The third incident was outside the Admiral Duncan public house in Soho, close to an area described as the ‘gay community’s heartland’. This bomb – also in a sports holdall – had been left behind in the pub by a man who had then walked out. The explosion killed three people, including a pregnant woman, and injured 139, four of them suffering the loss of a limb.

The police had examined many hours of footage from CCTV cameras in Brixton and managed to publicise pictures of the bomber on Thursday, 29 April, just under a fortnight after the Brixton incident. This caused the bomber to bring forward his plan to set off a third bomb by one day, and it was the reason for the Admiral Duncan public house explosion occurring on a Friday night rather than on a Saturday.

Just over an hour before that third bomb was detonated, an electrician from London Underground contacted police with the information that he believed the culprit to be his work colleague, David Copeland. Police investigated the information but it was too late to prevent the third bomb. The police called at Copeland’s address in Cove, Hampshire, on Saturday, 1 May and he immediately admitted responsibility for the bombs, claiming neo-Nazi political views. He had apparently acted alone, and his room contained Nazi flags and newspaper stories about bombs. It also contained over 500 items consisting of fireworks, pyrotechnics, firework casings and receipts for holdalls, clocks and nails, along with several terrorist handbooks.

Copeland’s trial was noteworthy for having no fewer than six psychiatrists giving evidence about his state of mind. They all found mental illness. Five of them diagnosed paranoid schizophrenia, the sixth a personality disorder that would not affect his legal responsibility for his actions. The prosecution did not accept his offer to plead guilty to manslaughter and persisted in their attempts to prove murder. He was indeed convicted of murder and given six life sentences. In 2007, the High Court decided that he should remain in prison for fifty years and this was upheld by the Court of Appeal in 2011.