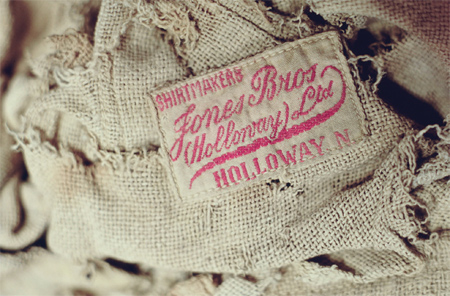

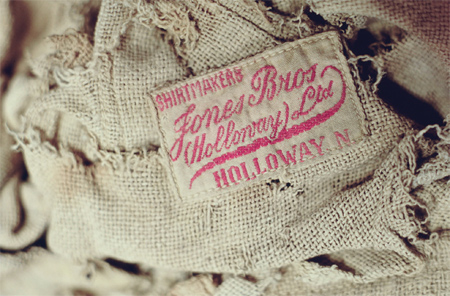

THE PYJAMAS, SUBSEQUENTLY identified as consistent with those owned by Dr Hawley Crippen, had been used to wrap up the remains of Cora Crippen, which were then buried under the cellar floor. Dr Crippen was in the habit of buying pyjamas in sets of three and the label, from Jones Bros of Holloway, matched two other sets found at his home at No. 39 Hilldrop Crescent. Evidence of the delivery of the pyjamas by the shop to Crippen’s home was introduced into his trial to link him with the remains.

The disappearance of Cora Crippen (also known as Belle Elmore), wife of Dr Hawley Harvey Crippen, is one of the most famous cases investigated by Scotland Yard. Crippen was an American doctor who came to England in 1900 to work in a patent medicine company. Cora Crippen had a stage career as a music hall singer but, by 1910, her involvement with the theatre was primarily as the treasurer of the Music Hall Ladies Guild. Cora Crippen was not seen alive after 31 January 1911 when the Crippens had entertained two retired artistes, Paul and Clara Martinetti, for supper. Two days later, her fellow committee members were surprised to receive two letters, apparently signed by Cora: one of them suddenly resigning from her post and the other informing them that she was to go to America to visit a sick relative. The letters were presented to them by Ethel le Neve, Dr Crippen’s secretary, who was later seen wearing Cora’s fur coat and jewellery.

A little while later, in March, Dr Crippen announced his wife’s death, but Cora’s friends were troubled by his vague explanations, the fact that they had not been been able to trace her in America and the suspicious status of Ethel le Neve in the Crippen household. Two of the friends, Mr and Mrs Nash, reported their concerns to Detective Chief Inspector Walter Dew, who started to make inquiries. These revealed that Cora's signature had appeared on cheques for the Crippens’ joint bank account up until 22 March, the day before Cora had, according to Crippen, been on her deathbed in America. Walter Dew went to Crippen’s house in Hilldrop Crescent, but only found Ethel Le Neve. He took her to Crippen’s office and interviewed him there, and back at Hilldrop Crescent, to be told that Cora had left Crippen for another man, leaving him with instructions to cover up any scandal in whatever way he could. For this purpose, she had signed a number of blank cheques. Crippen admitted that he had been having an affair with Ethel le Neve who, remarkably, told Dew that she had been ‘astonished’ to hear of Cora Crippen’s fate, but that she had not discussed the death openly with Crippen. Dew left Hilldrop Crescent to make further inquiries over the weekend to try to verify or disprove Crippen’s account.

By the Monday, Crippen and Ethel le Neve had disappeared. A search of the house eventually found human flesh and organs under the cellar floor, but no head or bones. The remains were found with Crippen’s pyjamas and there were traces of enough hyoscine (a medication used to calm violent patients in asylums) to have caused death. Dr Crippen had ordered five grains of hyoscine from a chemist’s establishment twelve days before Cora had last been seen alive. It was estimated that half a grain had been found in the dead body. Professor Augustus Pepper gave expert pathological evidence at Crippen’s trial, as did 33-year-old Bernard Spilsbury who went on to become a famous witness in many murder trials. Spilsbury testified that one section of a semi-horseshoe-shaped mark found on the flesh was consistent with a surgical scar for an operation that Cora Crippen was known to have undergone to remove her ovaries, despite defence claims that it was only a crease in the skin. Spilsbury had searched for evidence of glands or hair follicles, which would have indicated that it was not a scar, and found none. The other part of the horseshoe mark was indeed a fold or crease in the flesh.

The pyjama label

The international search for Crippen and Le Neve was concluded after Henry George Kendall, the captain of a cargo ship, Montrose, on a voyage from Rotterdam to Canada, reported his suspicions about two of his passengers to the ship’s owners by means of the new Marconi wireless transmitter. Ethel le Neve had been disguised as a boy, but the captain noted that the male clothes did not fit well, and that the ‘son’ of ‘Mr Robinson’ had a voice that began in a low register and became progressively higher. Sir Melville MacNaghten, the assistant commissioner, was asked to authorise Walter Dew and Sergeant Mitchell to travel to Canada by means of a faster ship, Laurentic, which was shortly due to leave Liverpool. MacNaghten’s decision to send Dew on a transatlantic pursuit would deprive Scotland Yard of its main investigating officer for more than three weeks. MacNaghten’s decision to allow the trip was a controversial one not supported by some of his colleagues, until, on the morning of 31 July 1910, news broke that Dew had boarded the Montrose and arrested Dr Crippen and Ethel le Neve.

Ethel le Neve was grateful to Walter Dew for arranging for some women’s clothing and a hat with a veil, which helped to hide her face from the curious crowds and newspaper reporters on her return to England. Crippen stood trial for murder at the Old Bailey in October 1910, was sketched by the courtroom artist William Hartley and was sentenced to death. He was hanged the following month. Ethel le Neve’s lawyers argued successfully for a separate trial and this may have saved her from the death penalty, which was a possible outcome of a joint trial with Hawley Crippen. She was acquitted.

1983

The wooden stool used to murder Peter Arne