![]()

ALL THESE PLACES HAD THEIR MOMENTS

HAMBURG

We got better and got more confidence. We couldn’t help it, with all the experience, playing all night long.

– John Lennon

Allan Williams was a Liverpool entrepreneur as enamoured with the rising music scene as the young Liverpudlians who were forming bands. He opened the Jacaranda club in 1958 with an eclectic booking policy. One of his favoured bands was Harold ‘Lord Woodbine’ Phillips’ All-Steel Caribbean Band. They told him that Hamburg had a buzzing club scene too and that the club owners were always looking out for bands. Sensing an opportunity, he made a recording featuring one of the top Liverpool beat groups, Cass and the Casanovas, and took it to Hamburg. There, he met Bruno Koschmider, manager of the Kaiserkeller, and talked up how the Liverpool scene was far more exciting than anywhere else in the UK. Unfortunately, when he played Bruno his tape, the recording was faulty, and he left Hamburg unable to back up his claims.

Then, a little bit of luck. In the summer of 1960, Williams found himself in Soho’s 2i’s coffee bar, the hub of London’s beat scene. By a happy coincidence Bruno Koschmider was in the audience, checking out bands. In yet another happy coincidence, Liverpool’s Derry and the Seniors were on the bill and smashed their set, blowing away the local bands, just as Williams had tried to convince Koschmider earlier. Williams secured a residency for Derry and the Seniors at the Kaiserkeller, and told Koschmider he had more bands he could send over.

The German entrepreneur also ran another club, the Indra, which he had decided to transform from a transvestite cabaret bar into a rock ’n’ roll venue. He asked Williams for a five-piece band, and the latter asked Rory Storm and the Hurricanes, Cass and the Casanovas and Gerry and the Pacemakers if they wanted to go over to Hamburg. They all said no. As a last resort he asked The Beatles – with Pete Best on drums they were now a five-piece – and they agreed. They all set off in a Morris J2 minibus, with their equipment and a tub of scones baked by George’s mum.

Liverpool had a reputation for being a tough city, but it was a playground in comparison to Hamburg and its St Pauli district in particular. The Reeperbahn teemed with pickpockets, prostitutes, pimps, strippers, sailors on leave and war-scarred ex-soldiers, who frequented the strip joints and bars. On arrival, The Beatles were shown to their digs – the backrooms of Koschmider’s Bambi cinema. One window, one electric light, no heating, no furniture except a couple of camp beds and a small couch, and a ceiling so low the band had to duck their heads. Their toilet was shared with the cinema’s customers. Assured that their accommodation was only temporary – it wasn’t – the band settled in, taking advantage of all the sensual delights the city had to offer (George lost his virginity on one of the camp beds with the rest of the band cheering him on), and got to work.

For around £15 a week, The Beatles had to play sets of four and a half hours Tuesday to Friday, and sets of six hours on Saturday and Sunday, with a day off on Monday. The band had a repertoire that could stretch to two hours at most, so they decided that rather than repeating themselves every night they would keep their shows fresh and exciting for the audience and themselves. They quickly expanded their set list, spinning out popular songs such as Ray Charles’ ‘What I’d Say’ (it could last a good forty minutes) and tackling the entire catalogue of their favourite artists, Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly. They introduced jazz standards and show tunes – ‘Summertime’, ‘Moonglow’, ‘Over The Rainbow’, ‘Bésame Mucho’ – to their set as well as early Motown and girl group material – ‘To Know Him Is To Love Him’, ‘Money (That’s What I Want)’ – to complement their rock ’n’ roll, bluesy and country numbers. Koschmider would loudly encourage them to ‘Mach schau!’ – put on a show – and The Beatles would respond by leaping about, stomping along to the music, acting up on stage and goading the audience. The punters lapped it up, sending drinks and requests to the stage in a raucous call-and-response. And if they got too rowdy, the waiters were always on hand with their fists or, on some occasions, tear gas, to calm things down . . .

So successful were The Beatles at the Indra that, due to noise complaints, they were moved to the bigger Kaiserkeller after Derry and the Seniors had finished their residency, and their contract was extended. Koschmider also brought in Rory Storm and the Hurricanes – they had finished their Butlin’s summer season – to share playing duties.

Rory Storm and the Hurricanes, long the top Liverpool band, were astounded by the change in The Beatles. They hadn’t been considered serious contenders back in Liverpool. Both bands started a friendly rivalry on stage, trying to outdo each other in getting the best audience reaction. Off stage, they would often socialise together, in particular with Rory Storm’s drummer, Ringo Starr, who would sit in for Pete Best when he was ill or unable to perform.

The Beatles also struck up a friendship with a group of young Germans who had become regular visitors to their shows. Klaus Voormann, Astrid Kirchherr and Jürgen Vollmer were cool art students inspired by existentialism as well as lovers of rock ’n’ roll. Both they and The Beatles influenced each other’s music, fashion and art, and Kirchherr, herself a talented photographer, fell in love with Stuart Sutcliffe. She took numerous photographs of The Beatles during their first trip, now iconic and among the best pictures of the band. Voormann went on to play bass with Manfred Mann as well as design the cover art for The Beatles’ Revolver album, and Vollmer later gave the band their moptop haircut.

But back in 1960, The Beatles had come to the attention of Peter Eckhorn, owner of the biggest live venue in Hamburg, the Top Ten Club. He approached them about a residency there, which The Beatles were keen to take up, particularly as their relationship with Koschmider was becoming increasingly strained. Just then, George, still only seventeen, was busted for being underage. At that time, Hamburg imposed a night-time curfew for the under-18s, so George was sent home.

Paul and Pete went to the Bambi to pick up their clothes and equipment to take to the Top Ten, and as a cheeky gesture to Koschmider, decided to stick condoms on the walls of their squalid digs and set them alight. Although the worst that happened was that they left greasy marks on the walls, Koschmider had them arrested for arson. He later dropped the charges, but Paul and Pete were sent home. John soon followed, dejected. Sutcliffe stayed on a little longer, reluctant to leave Kirchherr.

In April 1961, with George now eighteen, The Beatles headed back to Hamburg and straight to the Top Ten Club. They stayed in better digs this time, with Top Ten headliner Tony Sheridan – though Sutcliffe moved in with Kirchherr – and had to play seven-hour sets on weekdays and eight-hour sets on weekends. No days off. It was on this trip that the group were introduced to amphetamines, particularly Preludin (‘prellies’), to keep up with the relentless pace.

Hamburg was the city at the centre of the German recording business, and talent spotters would often drop in to the Top Ten Club. On a recommendation from a friend, Bert Kaempfert, an orchestra leader and music producer for Polydor Records, took in a Beatles performance and promptly signed them up for a recording session with Tony Sheridan. They backed him on his popular songs, ‘My Bonnie (Lies Over the Ocean)’, ‘When The Saints Go Marching In’, ‘Nobody’s Child’, ‘Take Out Some Insurance On Me, Baby’ and Sheridan’s self-penned ‘Why (Can’t You Love Me Again)’. They recorded two songs without Sheridan: ‘Ain’t She Sweet’ and a Lennon-Harrison instrumental ‘Cry For A Shadow’. Sutcliffe attended the sessions but he didn’t play on any of the tracks.

He was playing fewer gigs with The Beatles this time round and had applied to the art school in Hamburg, taking classes with Edinburgh-born artist and sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi. Sutcliffe decided to leave the band, and played an emotional final gig with them before John, Paul, George and Pete returned to Liverpool without him. Paul, though reluctant at first, became the group’s bass player.

In April 1962, on the cusp of signing a recording contract with Parlophone, The Beatles returned to Hamburg for a residency in the new Star Club, where they shared the bill with one of their musical heroes, Gene Vincent, for two weeks. Astrid Kirchherr flew to Liverpool, and the band met her at the airport. It was there that she told them the tragic news that Sutcliffe, who had been suffering from debilitating headaches, had collapsed and died with a brain aneurysm. The band, especially John, were shattered.

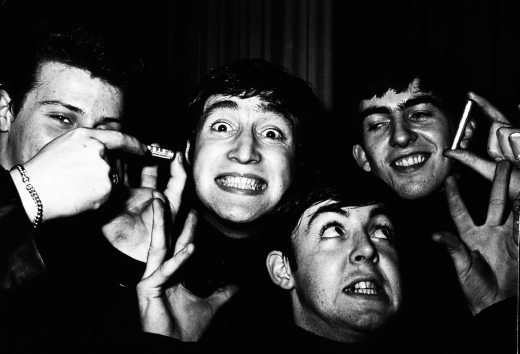

Mad-eyed Beatles showing off their Preludin in Hamburg. Getty Images

They returned to the Star Club in November to support Little Richard, this time with their new drummer, Ringo. ‘Love Me Do’ had just been released, and the band were reluctant to leave the UK, worried that their absence might hamper the single’s progress up the chart, but their manager Brian Epstein was adamant: they should honour their agreements. Fortunately, ‘Love Me Do’ went on to surpass Parlophone’s expectations, but there were grumbles when they had to travel back to Hamburg in late December 1962 for their final stint at the Star Club. During this last trip, the band were recorded on a reel-to-reel deck by Ted ‘King Size’ Taylor of The Dominoes, and this was later released as an album in 1977 as Live! At The Star Club, an amazing document of a band rough, ready, off the leash and on the cusp of stardom.