From the start, replacing the Mini was never going to be an easy task, and it is still regarded as one of the toughest challenges to face the automotive industry. After all, the Mini single-handedly reshaped the face of the motoring industry. In 1990, in Autocar magazine, a panel of 100 automotive experts voted the Mini the UK’s most significant car of the century, ahead of the VW Beetle, the Ford Model T and the Citroën DS.

Like most classic cars, the original Mini – the very first to leave the production line – was deemed irreplaceable: a car that should be left to grow old gracefully and never be altered. But that wasn’t enough to stop BMC and its ancestors from trying. A number of contenders tried to follow in the footsteps of the Mini and match its criteria, yet failed, mostly due to costs. Even Issigonis himself couldn’t produce another car in its league. The new MINI saw two manufacturers go head-to-head in a battle for the final say, yet they unwillingly worked together to produce the final masterpiece; so it turns out that the development of the new MINI was one of the most controversial in history.

The Issigonis 9X of 1968 was cancelled by BLMC due to costs, followed by the Barrel Mini that very same year. In 1973 the ADO74 was also cancelled by BLMC due to costs, and between 1974 and 1975 it was considered that it would be too costly to build the Innocenti Mini at Longbridge. In 1977 the ADO88 became the Metro. The 9X would have been the car to advance the Mini concept, which Issigonis himself had believed would be a certainty in 1970 in order to keep the Mini alive. But the Mini, of course, was no ordinary car, and the death of its never-to-become predecessor allowed the original to live on, and on, and on, just as it still does today.

Replacing the Mini was one of the most controversial challenges to face the industry. NEWSPRESS

Rover began to realize the Mini couldn’t continue in production in its original form.

Rover began serious work on the development project in the 1990s, when the A-Series engine was unlikely to pass emissions regulations and drive-by noise ratings. The fact that the A-Series engine had already been replaced by the K-Series in the rest of the range meant that the reasons to continue producing it had begun to wear thin, and it had become uneconomical. With safety becoming increasingly important and the requirement for airbags and the need to pass the EuroNCAP test just around the corner, the realization that the little Mini would be unable to accommodate such devices and therefore past the test was becoming a firm reality.

Not only that, the Mini itself was labour intensive, being mostly built by hand with a touch of good oldfashioned sweat and elbow grease. This made the Mini a car that workers at Longbridge found challenging to produce, and it would not continue. For this very reason the Metro would also need replacing. The UK’s automotive industry was about to begin work on one of the most controversial projects in all history. Rover’s attempt at rebuilding the Mini, which began in the year 1993, was soon strengthened by the arrival of BMW the following year. The outcome caused controversy amongst many enthusiasts, but went on to steal the hearts of thousands of buyers across the world.

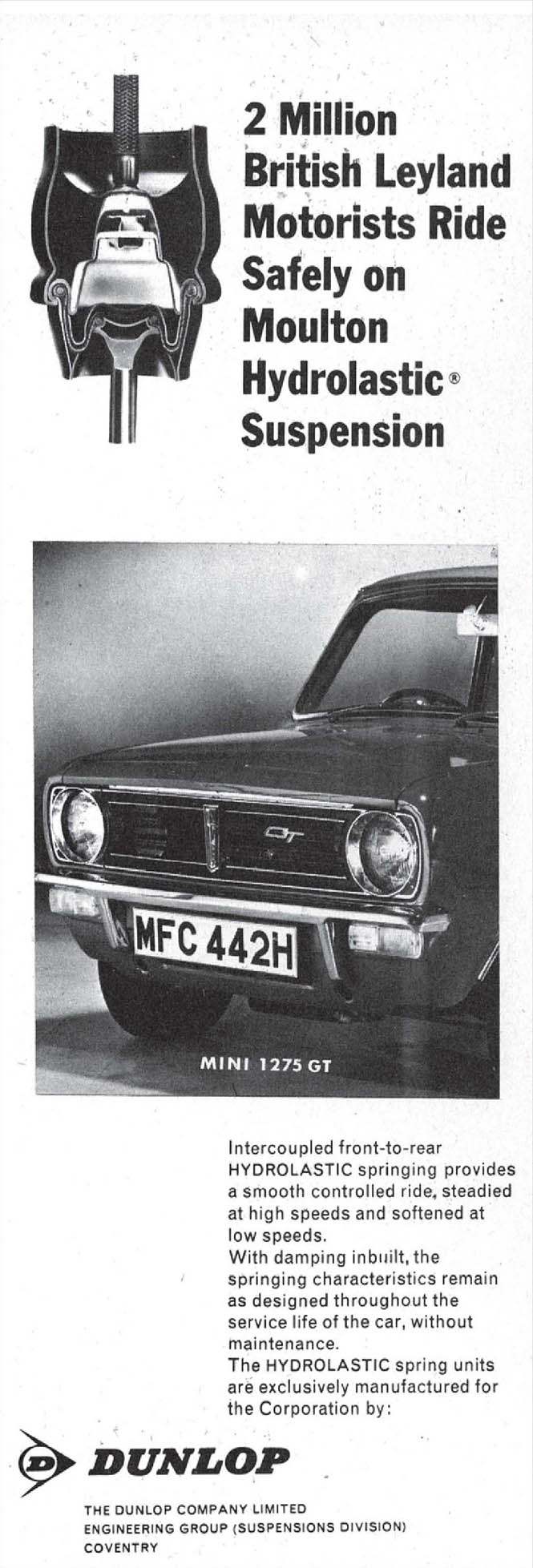

HYDRAGAS AND HYDROLASTIC SUSPENSION

Hydragas suspension was pioneered by British Leyland. When the Mini was launched in 1959, the British Motor Corporation (BMC) – British Leyland’s predecessor – was at the forefront of innovative automotive engineering. In the late 1950s, a system called Hydrolastic was founded by Dr Alex Moulton, designed to replace conventional suspension units with fluid-filled displacers containing a rubber spring, and interconnected with fluid-filled pipes to make them sit level. The original Mini was supposed to receive Hydrolastic suspension for its launch in 1959, but co-developers and Dunlop Tyres couldn’t produce small enough displacers in time. But not all was lost, and when the fast-selling 1100 was launched in 1962, the British nation soon became familiar with the ‘Moulton bounce’. In the 1960s, BMC refined the Hydrolastic system by fitting it to the Austin 1800, the Austin 3-litre, the Austin Mini and the Austin Maxi.

Then in 1970, the Hydrolastic system was replaced by technology that would forever be remembered for its association with the Austin Allegro. Hydragas cars had displacers that were partially filled with nitrogen, separated by a rubber membrane, thus providing an all-new form of suspension. As in the earlier cars, Hydragas suspension was interconnected: when a wheel hit a bump, the aim was for the suspension to compress, pushing fluid down the interconnecting pipe to the unit at the rear. This didn’t work particularly well on the early Allegros because the damping wasn’t strong enough, and engineers at Longbridge worked to resolve the issue by improving the system – not that Allegro customers would ever trust the suspension again. But all was not lost, because when Austin’s beloved Princess came along, it featured a refined Hydragas system, which resulted in a more than satisfactory ride and handling.

Sadly, by the time the Princess was launched in 1975, British Leyland was staring bankruptcy directly in the eyes. When Spen King – designer of the Rover SD1 and the Range Rover – was instructed to produce an efficient range of future BL cars, he decided that Hydragas was too complex and far too costly; as a result, the new Allegro and Maxi replacement lost Hydragas altogether and was given a carbon copy of the Volkswagen Golf’s MacPherson strut-and-beam axle set-up: this was the Maestro. But it wasn’t the end for Moulton’s creation – far from it, in fact. BL was still working on a new ‘super mini’, and due to company funds draining away like water, built a little car by throwing together Mini and Allegro parts. This was christened the Metro.

Hydrolastic suspension was founded by Dr Alex Moulton in the late 1950s. MAGIC CAR PICS

In 1993, the first design elements of the new Mini were shown at Canley design studios, but while Rover was racking its brains for ideas of how to go about replacing the Metro, it made perfect sense that this new car would replace both. Product design director Gordon Sked at Rover Group worked with his design team to produce a variety of ideas for the new Mini, no matter how eccentric or adventurous they turned out to be. The Mini was neither subtle nor restrained, and this was to be highlighted through its appearance. This resulted in the designers, including David Saddington and David Woodhouse, drawing up an entire range of potential Mini models. A number of concepts was considered, including the threeseater city car with McLaren styling and a prototype nicknamed the ‘Minki’ – featuring the K-Series engine and Hydragas suspension – but Rover soon found itself being sold to the mighty manufacturer BMW, and had no idea how the Bavarian Motor Works company would approach the Mini project.

To begin with, the Rover designers were relieved to find that the head of BMW, Bernd Pischetsrieder, was more than happy for them to carry on with their original design briefs to shape the new Mini. Being the great-nephew of Issigonis himself, Pischetsrieder was very well aware of the Mini’s great sentimental value to the British population, and felt that it was important for the Rover team to work independently from the BMW headquarters in Munich, Germany. After all, who was better placed to design and build the new British icon, other than the British themselves? After providing the funding to continue the Mini rebuild alongside a real codename – R59 – Pischetsrieder even made it his responsibility to build a trustworthy project team, recruiting the remaining masterminds of the original ADO15 project. These included John Cooper, Jack Daniels and Alex Moulton.

Inevitably, in 1994 the German car maker was keen to get more involved with the new Mini replacement project. Stylists in Munich were already working on new proposals for a modern-day Mini, and it turned out that their visions of the new car differed greatly from those of Rover. While David Saddington, who had been promoted to design director of MG and Mini, wanted to produce another car that closely resembled its predecessor, the rest of the Rover and BMW clan had fresh ideas in mind. It was clear by this point that ‘the car’ was becoming more than just a car: it was now a fashion icon that needed to be equipped with higher standards of safety equipment and in-car gadgets, to produce low economy figures, and – even for a Mini – to boast more cabin space – where imagination meets practicality. Of course, combining each of those key elements was never going to be an easy target.

BMW focused on designing a new Cooper, wondering what the car would have looked like if it had gone on to become a continuous design project like the beloved Porsche 911. NEWSPRESS

At the time, Chris Bangle – labelled as one of the most controversial designers in automotive history – was busy conjuring up a design recipe that would both please and disgust. He was working on a new ‘Mini Cooper’, with a goal to produce a brand new car that wouldn’t be overshadowed by the classic. In his eyes, the new Mini was to be an all-new icon car in its own right. By this stage, BMW was focusing on producing a new Cooper, rather than just a Mini, desperately trying to imagine what the car would have looked like in the mid-1990s had it gone on to become a continuous development project in the same way as the beloved Porsche 911. Enter BMW’s product development chief Wolfgang Reitzle – the man who battled with Joachim Milberg to secure the BMW chairman’s seat in 1999, and lost – and enter the problem: Rover was adamant on building an eco-friendly runaround, while BMW was determined to produce a small sports car – what we now call the ‘hot hatch’.

In 1995, Rover revealed their idea for the new Mini, which turned out to be exactly what we all predicted: a four-seater cube, following in the path of a K-Series engine, subframes, and of course Hydragras suspension. Meanwhile, BMW was working on another alternative, featuring a rear Z-axle and MacPherson struts at the front. There was only one solution: on 15 October 1995, BMW and Rover designers gathered at the Heritage Motor Centre in Gaydon to present their full-scale prototypes – you can only image the tension between the two brands. While Rover’s three model proposals were documented – the Evolution, Revolution and Spiritual – BMW refused to record exactly what, or how many cars they presented. The Spiritual proposals, called Mini and Midi, were said to have been shown in long-wheelbase form, proving that the design could also work in a larger package. Meanwhile, BMW’s models represented sporting cars, none of which paid homage to Issigonis’ original, aside from details of retro exterior styling. The mastermind behind one of these cars was American automotive designer Frank Stephenson.

Pischetsrieder, Reitzle and the Rover board members would have the final say as to which designs were to be taken forwards, and both Stephenson’s and Saddington’s models caught their attention. They decided these models captured the conventional small car qualities and combined them with the retro sporting appeal that the two manufacturers were looking for. Pischetsrieder was impressed by Rover’s concepts, but believed they were too far ahead of their time – he was looking for a simple design that wouldn’t age too quickly, but would also fit in with the current-day motoring crowd, enabling the company to get the car into production as quickly as possible. Rightly so, he was looking for a car that would reflect the spirit of a Mini for the twenty-first century. The Spiritual concept was therefore pushed aside, regardless of Rover’s efforts to push it forwards. However, its spacious qualities were recognized as a crucial element for the new car. In the end, Rover’s head of design Geoff Upex made the final decision. At the time, it was probably seen as a shocking choice, but today it was arguably predictable. Upex appointed Saddington to be the car’s design chief, leaving the Brits in charge of the overall Mini package, and American designer Stephenson responsible for its styling.

In 1995, Rover and BMW gathered at the Heritage Motor Centre, Gaydon, to reveal their designs. Rover’s turned out to be what we predicted: a four-seater cube with Hydragas suspension. MAGIC CAR PICS