Developing the new Mini was never going to be a smooth procedure. Saddington and Stephenson would continue to argue over designs, while they learned that packaging the new Mini was tougher than expected. Project management and engineering was handled by BMW in Munich, while Stephenson was working as a BMW employee within Rover back in Gaydon: this meant that little progress was made. Therefore in May 1996 the entire project was handed back to Rover, renamed Project R50, and managed by new project director Chris Lee. This didn’t bode well with the Munich team, so BMW’s development chief Burkhard Goeschel was sent to oversee the handover, which then became rushed. The Rover team had inherited a BMW platform – which had been decided upon in 1995 – but no one knew which engine and gearbox it would run, and even worse, no one had informed Moulton or BTR Development that their work on the new Mini was no longer required, leaving the ‘Minki II’ prototype, which had met all the requirements asked of it by BMW, redundant by September 1996.

By the end of 1996 it became apparent to Rover that the Mini’s new chassis decisions were firmly in BMW’s hands. To ensure there were no slip-ups, BMW organized a new, second team to be set up in Munich. This team would act as a guardian for Rover, someone the team back in Britain could call upon during the development of the new car. As you can imagine, this process was not particularly helpful or welcomed. The manager of the R50 project, Chris Lee, became what you might refer to as the ‘piggy in the middle’, trying to make sense of and find peace between the two sides.

If that wasn’t enough, Rover itself was also having issues with Wolfgang Reitzle, who had frozen the R50’s styling when the engine and gearbox had yet to be confirmed. On Rover’s behalf, Saddington had already made his concerns clear by highlighting the fact that by using the existing low bonnet line, the K-Series engine would be a worryingly tight fit, and therefore pressed the point that it should be raised. But meanwhile, on the other side of the fence, BMW blamed the K-Series engine for ‘not having a spaceefficient package’. According to the press, Wolfgang Reitzle took upon himself to tell Saddington that he would fix the problem, without actually stating how and when he would do it.

In May 1996, the project was codenamed R50 and directed by Chris Lee. MAGIC CAR PICS

It is possible to imagine the frustration of the engineers working on Project R50, since the car they were now preparing was no longer the car they felt was destined to replace the Mini – BMW had well and truly taken over the project, and there was no turning back. If losing all say over the new vehicle’s design elements wasn’t enough for the engineers back at Gaydon, in Warwickshire, Wolfgang Reitzle stayed good to his word and eliminated another question hovering over the project, when he later announced that BMW would co-develop a brand new engine for a brand new Mini with Chrysler, which was to be built in Brazil. That’s right: the K-Series engine – the replacement for the original A-Series unit – was no longer a contender for the new car.

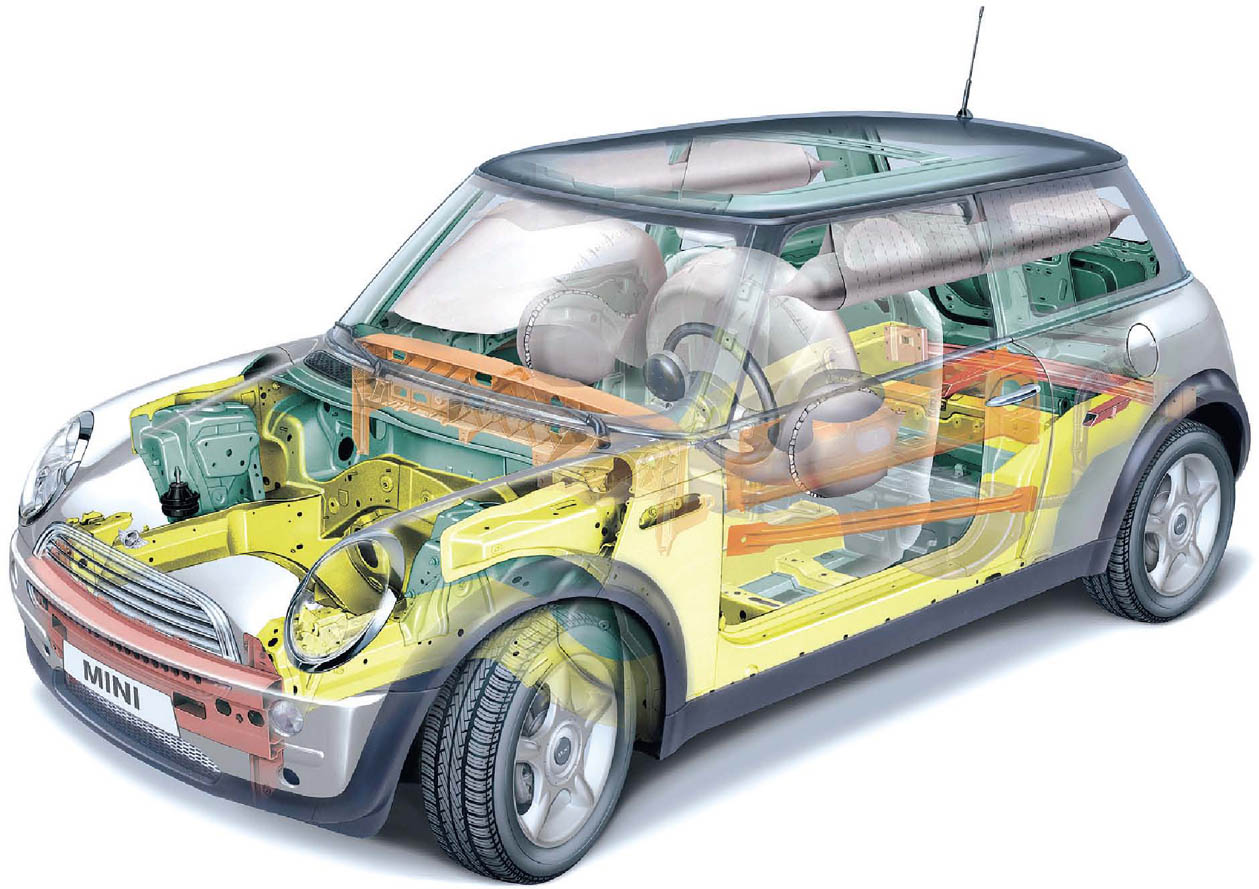

It is important to remember that, although the majority of decisions surrounding the MINI project were made by BMW, it was in fact the British engineers from Rover who carried out most of the work, specifying and designing components at Rover’s engineering centre at Gaydon. The only requirements set by BMW were the MacPherson strut front and rear Z-axle formation. Even the MINI’s engine and gearbox were engineered at both Longbridge and Gaydon, and at this point there were possibly more than 400 British engineers working on the new MINI. Although BMW was set upon having a Getrag gearbox for the new car, the UK team mated the engine to a Midland R56 transmission instead, mainly because it was £100 per car cheaper and it was more compact. The R56 gearbox was far from being a new creation, since it was already being manufactured at the Longbridge site and was making an appearance in front-wheel-drive Rover cars. It was an easy argument to win, but by keeping evidence of back-to-back tests as well as performance and service evaluations, the Brits eventually won the battle with Rover’s R56.

Once the engineers knew what would be at the heart of the new MINI, they could finally make focus on the final build, producing what would become the ‘production release’ or ‘concept’ cars. The Rover team began development with simulators, of which there were two versions: Rover 200s with a mock Mini chassis, and 200s with the new MINI’s Pentagon engine. All the while the engineers had to remember the main aim of the game: to produce the best handling front-wheel-drive car in the world. It turns out that the rear Z-axle set-up was a hit. Any talk of wishbones was frowned upon, however, since BMW insisted that the MINI was a BMW and therefore had to feature struts. Due to having a compact front end, it was inevitably difficult to set up the suspension and minimize torque steer.

To Rover’s horror, BMW was adamant that the new car would have no resemblance to the original – or at least, it wouldn’t be based on the same foundations. BMW’s MINI would be a new car in its own right, marking the beginning of a new era and one that had a spot in the future. But that didn’t stop the original Mini running alongside the new one – and in fact, in most cases, the little Mini continued to outshine its successor, championing in motor racing, thrilling crowds at shows and altogether stealing the limelight. BMW were going to have to pull something out of the bag to make it work.

The MINI was to be a small, premium hatchback, meaning its price tag was inevitably going to rise, but not quite reaching the figures of BMW cars such as the 3 Series. However, the fact that the new car was destined to target BMW rather than Rover buyers meant that the extra cash needed to own one of these little cars wouldn’t be too much of an issue. BMW already boasted a global dealer network of more than 4,000, and since the brand was (and still is) renowned for its high quality cars, surely they’d have no problem selling this new one under the BMW umbrella alongside Land Rover, MG and Rover? Well, you’d think not. But for many Mini enthusiasts, the new car was an insult. It was too big and too German. How could it possibly replace the British pocket-rocket?

The ACV30

It was the ACV30 concept of 1997 that gave us the first real glimpse of BMW’s direction for the little car. They actually announced this car – a retro-styled coupé – at the Monte Carlo Rally. It was built on an MGF chassis, and reflected similarities of the Dream-works proposal of the new car at Gaydon in 1995. While it is clear to see that this concept does carry some familiar BMW MINI DNA, its appearance did little more than prove to the world that Rover and BMW were working seriously on a replacement for the Mini, and that it would be vastly different to the car they knew all too well. Nevertheless, it did help to soften some peoples’ views on the arrival of the new car, and at last they weren’t preparing for the unknown, but were contemplating the sight of what could be the new car. Features such as the centrally mounted speedometer were present in the ACV30 concept, and filtered down into the MINI we know today. In fact, the centralized speedometer is one of the MINI’s most symbolic assets, along with the rest of the interior, which was inspired by the ACV30 and tweaked by Britons Wynn Thomas and Tony Hunter.

The ACV30 MINI Anniversary Concept Vehicle, which celebrated twenty years of the hat-trick of Mini wins at the Monte Carlo Rally, pictured here with Rauno Aaltonen’s Monte-winning Mini Cooper LBL 6D. NEWSPRESS

AVC30 was built on an MGF chassis and resembled BMW-styling characteristics. MAGIC CAR PICS

The AVC30 1997 gave us a glimpse of what the BMW MINI would look like. MAGIC CAR PICS

Next up was the Rover Spiritual, which made an appearance at the 1997 Geneva Motor Show. Designed by Oliver Le Grice, the Spiritual was what we’d call a rear-engined city car today. Issigonis would not have been impressed with the engine set-up, since he believed that rear-engined, rear-wheel-drive cars were unsafe and should be banned by the law. The Spiritual was just 10ft (3m) long, too, just like the original Mini. It was also designed with a short and long wheelbase, with the longer version christened the Midi. Like the ACV30, the Spiritual had been taken to Gaydon in 1995 to decide which car would eventually go into production. It was said to be at least a decade ahead of its time, earning praise from BMW Group boss Bernd Pischetsrieder, though it didn’t earn too much praise from the public.

Sadly, neither the ACV30 nor the Rover Spiritual ever made it past the concept stage, and they remain another figment in the ‘Mini makeover’ history books. By this point both the public and the media were on tenterhooks, waiting for the official unveiling of THE new mock-up MINI: this would be revealed at the Frankfurt Motor Show just a few months later.

THE FIRST RUNNING CONCEPT OF THE MINI

When the first running concept of the MINI was revealed at the Frankfurt Motor Show, its interior resembled that of the ACV30, and we would come to learn that it was identical to the car that would be launched two years later in production form. However, at this point the MINI was nowhere near ready for production – this mock-up concept was based on a modest Fiat Punto. But there was some good news, with the overall atmosphere surrounding the MINI becoming much more positive, even between BMW and Rover. But that’s not to say that it stayed that way, since Rover and BMW were arguably as compatible as chalk and cheese. The final stages of the MINI development progressed as you’d expect: more prototypes were designed and built, road-testing commenced, and it also took quite a thrashing around the Nürburgring in Germany to tweak and finalize the car’s set-up. BMW has been fine-tuning chassis at the world’s most iconic yet treacherous racing circuit for generations. So while BMW took over testing, Rover was in charge of production, with the new MINI still destined to be built at the factory in Longbridge. But the trials and tribulations continued in the final build-up.

To Rover’s surprise, BMW’s development chief Burckhard Goeschel fired the MINI project director Chris Lee, which wasn’t exactly the most appropriate timing, and was arguably unjust treatment for a man who had dedicated so much time and effort into getting the final MINI ready for production. Nevertheless, the show must go on, and the MINI story continued with one more hurdle to jump. The two big names at BMW – CEO Pischetsrieder and product development chief Reitzle – resigned from the brand and therefore the project. Rover’s ally, at the head of the brand, had disappeared, leaving the British team helpless to defend its role in the final build stages. Instead, BMW placed project R50’s original brand director Heinrich Petra back in the driving seat, and stripped Rover of all its responsibilities. Once again, this little car in the making was causing quite a stir, with two manufacturers battling for the limelight. Would the new MINI ever be completed?

In 1999, the final development of Project R50 was taken under the wings of BMW. But the majority of the engineers who had worked endless hours for more than three years to create the new car stood their ground and remained in Britain with Rover. Times were bleak, and the head of the venture capital group Alchemy Partners Jon Moulton agreed to buy loss-making Rover cars from BMW, ending Rover’s days as a mass-market car maker and posing a threat to at least half of the 10,000 people working at Longbridge. Jon Moulton eventually backed down, leaving the way for the Phoenix consortium to buy the firm. According to the BBC, Jon Moulton said through gritted teeth that the government’s role in backing Phoenix helped BMW save £ 1bn: ‘The government made it easy for BMW to get out of Rover at a relatively low cost.’

The MINI was finally launched at the Paris Motor Show in the year 2000. MAGIC CAR PICS

The BBC also released a quote from a spokesman for former government minister Stephen Byers, assuring that the new owners of Rover were focused on making the firm a mass-market manufacturer once again: ‘Our position at the time was to safeguard jobs. It was a commercial decision by BMW.’ At the beginning of the year 2000, Longbridge’s involvement with the new MINI came to an end, and BMW was keen for all digital files and documents surrounding Project R50 to be downloaded on to German hard drives – the brand was aiming for a January 2001 sale target, and the partnership with Rover was over.

The MINI was at the heart of the one of the greatest conflicts in the automotive industry, and was dragged into BMW’s MG Rover sell-off in the year 2000. John Towers, one of the four businessmen who founded the Phoenix Consortium, is said to have pleaded with BMW to allow the car to remain under British control, with production beginning at Longbridge as originally planned. It was no surprise that BMW broke this promise. The brand had already seen what the power of the Mini mark could do, especially in Britain, and wanted to keep the success story all to itself. BMW had the MINI’s production facility moved to Cowley, now known as BMW Oxford or Oxford MINI, which saw the production of Rover 75 vehicles moved to Longbridge. Thankfully, that was the end of the conflict.

Four years after the prototype had been revealed, the first MINI rolled off the production line at Plant Oxford in 2001. NEWSPRESS

LAUNCHING THE MINI

The MINI was finally launched at the Paris Motor Show in the year 2000, with BMW insisting that the brand name would be capitalized. The MINI was to be a game changer, and the media knew that. The entire management team made an appearance at the big unveiling, with BMW’s development chief Burkhard Goeschel and chief designer Frank Stephenson on hand to answer questions surrounding the MINI as a product when the cover was finally whipped from the car for the crowds to see. At the show, Stephenson said: The MINI Cooper is not a retro-design car, but an evolution of the original. It has the genes and many of the characteristics of its predecessor, but is larger, more powerful, more muscular and more exciting than its predecessor.’

Since it had been four years since the new car had been revealed in prototype form, buyers were keen to place their orders and the journalists were keen to get in it, which inevitably wouldn’t take long. The first MINI to hit the UK market rolled off the production line in July 2001. BMW remained original with their marketing ideas, with a ‘MINI adventure’ campaign, well packaged to target the young drivers whose parents understood the importance and heart-warming memories of the classic, which they undoubtedly once owned themselves and held dear to their hearts – although when it came down to it, many Mini enthusiasts were bitter towards the new car, which was to be expected. After all, it wasn’t technically a British-owned car, and resembled very little of Issigonis’s Mini they had come to adore. But the new car was, and still is, a Brit at heart, mostly because of the hundreds of British engineers who didn’t give up on the development of Project R50.

Alex Moulton of Moulton Developments Limited – the man who designed the suspension for BMC’s Mini, the founder of Hydrolastic and Hydragas suspension systems, and a friend of Issigonis himself – was particularly unimpressed with the new car. He was one of the first critics to argue that the MINI was far too big to be of the Mini bloodline. According to the press, he said:

It’s enormous. The original Mini was the best packaged car of all time. This is an example of how not to do it – it’s huge on the outside and weighs the same as an Austin Maxi. The crash protection has been taken too far – I mean, what do you want, an armoured car? It is an irrelevance so far, as it has no part in the Mini history.

On the other hand, the legendary John Cooper was very impressed, later lending his name to the performance model of the new MINI – the MINI Cooper S, John Cooper Works.

MINI celebrated its launch year with a MINI Christmas tree at the Tower of London. NEWSPRESS

After forty-one years, the Mini was finally reincarnated. Little did the UK or even the world know that, while this car would make many enemies and allies upon its arrival to the market, the MINI would become a modern motoring legend, a car that would eventually win the hearts of thousands of motorists, and park proudly alongside the classic Mini we all adore, at hundreds of car shows across the globe. The Mini to MINI story has been a hugely successful one, and no success story is founded without its scruples. Although many still remain sceptical, the majority of the members of true Mini fan clubs have accepted the new car. Visit any Mini-focused show and you’ll sell a mix of both old and new. It may have caused one of the largest motoring conflicts in history, but when the R50 was launched in the year 2000, its purpose was never to replace the Mini: it was to continue its legacy.

The new MINI was gifted with a rather unique interior to match its outer styling. MAGIC CAR PICS