South Indian bronze showing deer in Shiva’s hand

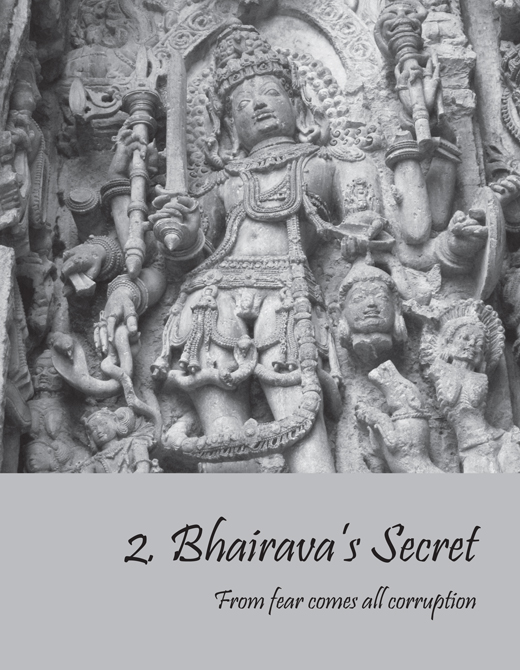

Bhaya means fear. And the greatest fear of all living creatures is death. Yama is the god of death. We fear him. We do not want to die. We want to survive.

To survive, we need food. But to get food we have to kill. Only by killing a living creature can food be generated. If the deer has to eat, the grass has to die; if the lion has to eat, the deer has to die. The act of killing and the act of feeding are thus two sides of the same coin. Death ends up sustaining life. This is the truth of nature. Shiva is called Kaal Bhairava because he removes the bhaya of kaal, which is time, the devourer of all living things.

Fear of death leads to two kinds of fears as it transforms all living creatures either into predator or prey. The fear of scarcity haunts the predator as it hunts for food; the fear of predation haunts the prey as it avoids being hunted. Nature has no favourites. Both the lion and the deer have to run in order to survive. The lion runs to catch its prey and the deer runs to escape its predator. The deer may be prey to the lion, but it is predator to the grass. Thus no one in nature is a mere victim. Without realising it every victim is a victimiser, and there is no escape from this cycle of life.

Fear of death creates the food chain comprising the eaters and the eaten. Fear of death is what makes animals migrate in search of pastures and hunting grounds. Fear of death establishes the law of the jungle that might is right. Fear of death is what makes animals establish pecking orders and territories. Fear of death makes animals respect and yearn for strength and cunning, for only then can they survive.

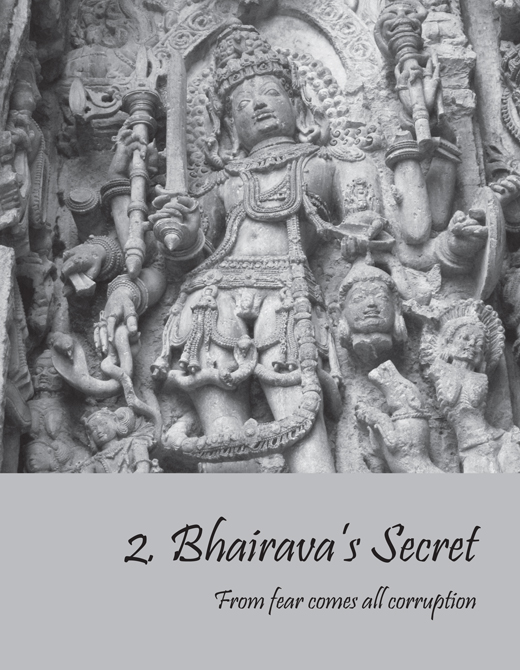

The male head that is often placed over a Shiva-linga

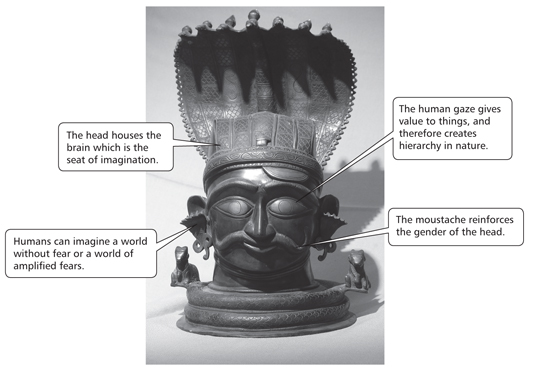

Stone carving of headless female body known as Lajja-gauri

Such behaviour based on fear is appropriate for the beast or pashu, but not humans. Humans have imagination and hence the wherewithal to break free from animal instincts. Humans need not be territorial or dominating in order to survive. Humans need not form packs or herds in order to survive. Humans can break free from the fear of death, shatter the mental modifications emerging from time. Humans need not be predator or prey, victim or victimiser. Shiva, who rises out of the endless pillar of fuel-less fire, shows the way.

Shiva reveals the power of the higher brain over the lower brain, the human brain over the animal brain. That is why he is called Pashu-pati, master of animal instincts. He offers the promise of a-bhaya, the world where there is no fear of scarcity or predator, in other words no fear of death. Shiva offers immortality.

Because humans have the ability to imagine, humans stand apart from the rest of nature. This division is the primal division described in the Rig Veda. On one side stands nature, the web of life, the chain of eaters and eaten. On the other stands the human being who can imagine a world where the laws of the jungle can be disregarded, overpowered or outgrown. Humans therefore experience two realities: the objective reality of nature and the subjective reality of their imagination. The former is Prakriti; the latter is Purusha.

Prakriti is nature who has no favourites. Purusha is humanity that invariably favours a few over the rest. In art, Prakriti is visualised as the female body without the head while Purusha is visualised as the male head without the body.

Painting from Nepal of Bhairavi, the fierce mother goddess

The head is used to represent Purusha because the head houses the brain, which is the seat of imagination. The body without head then comes to represent Prakriti.

The body’s gender is feminine because the head has no control over the natural menstrual rhythms of the female body; the arousal of the male body is, by contrast, influenced by the head.

The head’s gender is masculine as indicated by the moustache because the male body can create life only outside itself within a female body, just as imagination can only express itself tangibly through nature.

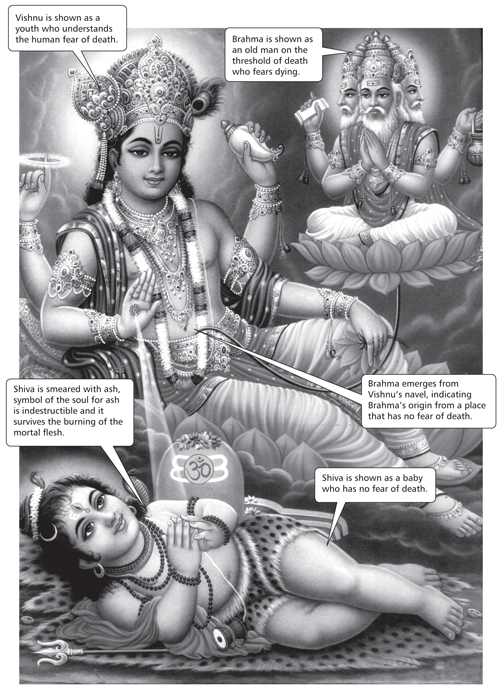

Nature creates and destroys life without prejudice. Human imagination is the seat of prejudice. It has two choices: to imagine a world without fear or to imagine a world with amplified fears. When the Purusha outgrows fear and experiences bliss, it is Shiva, the destroyer of fear. When Purusha amplifies fear and gets trapped in delusions, it is Brahma, the creator of fear. Naturally, the former is considered worthy of worship, not the latter.

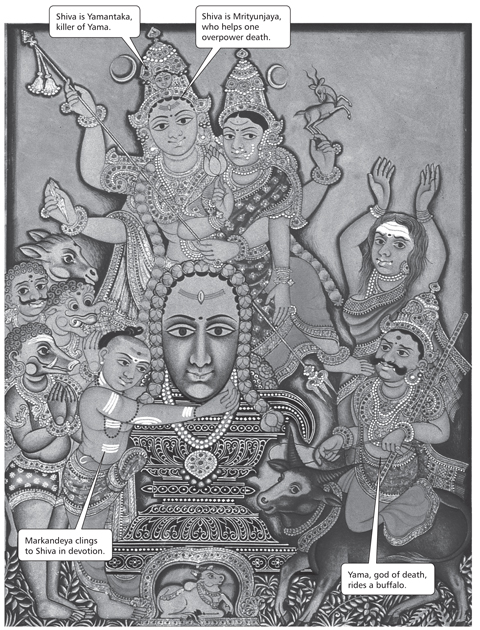

A childless couple were once offered a choice: a wise son who would live for sixteen years or a foolish son who would live till he was hundred. The Rishi chose the wise son. In his sixteenth year, Yama, the god of death, came to claim the son who had been named Markandeya by his parents. Yama found Markandeya worshipping a Shiva-linga. ‘Let me finish my prayers and then I am ready to die,’ said Markandeya. But death waits for no man or prayer. Yama hurled his noose and dispassionately started dragging the boy towards the land of the dead. The boy clung to Shiva’s linga and fought back. Yama refused to give up and yanked the boy forcefully. The tug-of-war between the boy and the god of death ended when Shiva emerged from his linga and kicked Yama away. Markandeya declared that Shiva is Yamantaka, he who destroys Yama. Markandeya became the immortal sage.

Mysore painting showing Shiva overpowering Yama

In this story, wisdom is intertwined with immortality. One becomes immortal when one outgrows the fear of death. Markandeya does at the age of sixteen when he clings to the Shivalinga, which is the symbol of Purusha or spiritual reality. This is a metaphor for faith. Faith is not rational just as immortality is not natural. Immortality is an idea that appears in the human imagination in response to the fear of death. When one liberates oneself from the fear of death using faith, one becomes indifferent to death. Death then no longer controls us or frightens us. We are liberated. We achieve immortality.

Shiva’s ash draws Markandeya’s attention to immortality. Shiva smears himself with ash to remind all of the mortality of the body. When a man dies, his body can be destroyed by fire. What outlives the fire and the body is ash, which is indestructible. Ash is thus the symbol of the indestructible soul that occupies the body during life and outlives the body in death. The soul is atma.

Markandeya realises only the fool derives identity from the temporary flesh; the wise look beyond at the permanent soul. Flesh is tangible but the soul is not. Flesh is fact but soul demands faith. Atma defines all laws of nature — it has no form, it cannot be measured, it cannot be experienced using any of the five senses. It is a self-assured entity that does not seek acknowledgment or evidence. One has to believe it. There is no other way to access it.

Brahma has no faith. He refuses to look beyond the flesh. He ignores atma, and so catalyses the creation of aham, the ego.

Poster art showing birth of Brahma

The ego is the product of imagination. It is how a human being sees himself or herself. It makes humans demand special status in nature and culture. Nature does not care for this self-image of human beings. Culture, which is a man-made creation, attempts to accommodate it.

Brahma is every human being. He is described as emerging from a lotus. This is a metaphor for a child emerging out of the mother’s womb. This is also a metaphor for the gradual unfolding of the imagination.

Birth is not a choice. And survival is a struggle, a violent struggle, plagued by fears of scarcity and predation. This is true for plants, animals and humans. But only humans can reflect on these fears and resent it and seek liberation from it.

Imagination makes Brahma think of scarcity in the midst of abundance, war in times of peace. Though he can rein in his fear, he ends up exaggerating fear. He assumes he has no choice in the matter. Like Markandeya, he can imagine Shiva, but unlike Markandeya he does not have faith in Shiva. He therefore does not discover atma, and finds himself alone and helpless before nature, a victim. Who is the cause of this misery, he wonders. Is nature the villain?

Who came first —the victim or the villain, nature or humanity, Prakriti or Brahma? Objectively speaking nature came first. Nature is the parent. Humanity is the child. Subjectively speaking, however, imagination caused the rupture between humanity and nature, imagination forced Purusha to visualise itself as distinct from Prakriti. That makes nature the child. Humanity then is the parent. Thus Prakriti is both parent and child of Brahma. He depends on her for his survival, but she is not dependable. She is the cruel mother and the disobedient daughter. He feels ignored and abandoned and helpless and anxious. He blames her for his misery. In fear, he allows his mind to be corrupted.

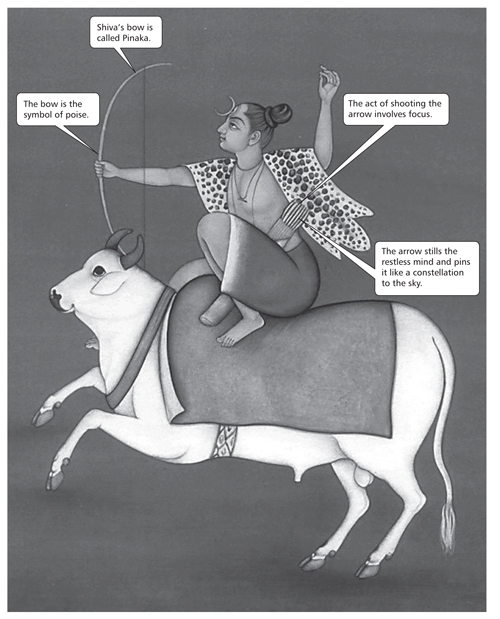

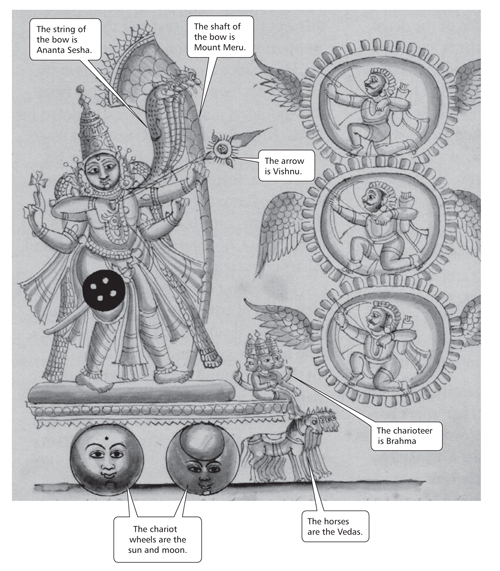

North Indian miniature painting showing Shiva as Pinaki, the bearer of the bow

Brahma’s expectations of Prakriti are imaginary. Nature does not love him or hate him. Nature has no favourites. All creatures are equal in Prakriti’s gaze. Because Brahma can imagine, he imagines himself to be special and so expects to be treated differently by nature. This is because of the ego.

Brahma renames Prakriti as Shatarupa, she of myriad forms. Some forms nourish him and make him secure. Others frighten him. Brahma seeks to control nature, dominate and domesticate Shatarupa so that she always comforts him. Unlike the Tapasvin who sought liberation from nature, Brahma seeks to control nature.

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad describes how Shatarupa runs taking the form of various animals and how Brahma pursues her taking the form of complementary male animals. When she runs as a goose, he pursues her as a gander. When she runs as a cow, he pursues her as a bull. He becomes the bull-elephant when she is the cow-elephant; he becomes the stallion when she is the mare; he becomes the buck when she becomes the doe. Shatarupa’s transformations are natural and spontaneous. Brahma’s, however, are the result of choice — he chooses to derive meaning from her, be dependent on her and in the process loses his own identity. The autonomy of his mind is thus lost, its purity corrupted, as it grows attached to the world.

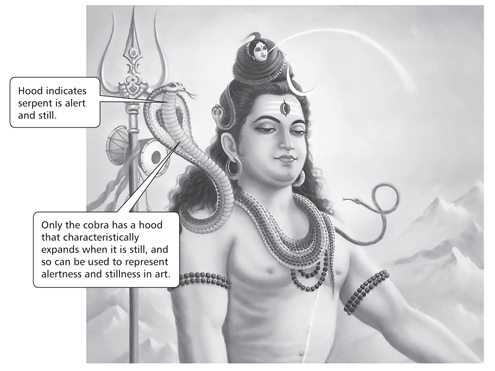

Poster art showing a hooded serpent around Shiva’s neck

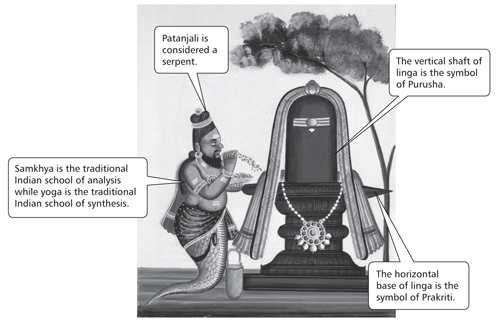

South Indian painting of Patanjali, the author of the Yoga-sutra

Brahma’s chase of Shatarupa thus entraps him. It is the movement away from stillness and repose towards fear and restlessness, symbolically described as a southern movement, away from the still Pole Star. To stop him, Shiva takes the form of a bowman and raises his bow, the Pinaka, and shoots an arrow to pin Brahma to the sky. In other words, Shiva stills the mind.

The bow is the symbol of concentration and focus and balance, in other words, it is the symbol of yoga. Yoga is a set of practices that stills the restless mind. It is what can pin the deer down. The word yoga comes from the root yuj, meaning to align. Fear destroys the alignment of the mind; rather than accept the reality of nature, the mind seeks to change and control it. These attempts invariably fail, creating frustration and fear and confusion that blinds one to spiritual reality. Yoga restores mental alignment so that nature is seen for what it is. Witnessing Prakriti will provoke the journey towards Purusha. Rather than blaming nature or clinging to the flesh, one will find refuge in atma. Shiva is therefore called Yogeshwara, lord of yoga.

Seated coiled around Shiva’s neck is the hooded cobra. The cobra is unique amongst all serpents as it possesses a hood that it spreads whenever it is still. The hooded cobra around Shiva’s neck thus represents stillness which contrasts the restlessness of nature. Shiva pins Brahma down so that he stops and observes nature’s dance, and aligns himself with her rhythms rather than manipulating them to suit his whims.

It is said that the serpent around Shiva’s neck is Patanjali who wrote the Yoga-sutra, the aphorisms of yoga. In it, he defines yoga as the unbinding of the knots of the imagination. Brahma creates these knots as he pursues Shatarupa; Shiva destroys them.

Poster art of Batuk Bhairava

In the Linga Purana, Shiva howls when he witnesses Brahma chasing Shatarupa. It is a howl of despair and disgust. He mourns the corruption of the mind. Shiva, the howler, is called Rudra.

Rudra watches as Brahma sprouts four heads facing the four directions as he seeks to gaze upon Prakriti at all times in his attempt to control her. Brahma then sprouts a fifth head on top of the first four. These sprouting of heads refer to the gradual contamination of the mind, its knotting and crumpling with fear and insecurity as the desire to dominate and control takes over.

The first four face the reality of nature in every direction; the fifth simply ignores the reality of nature. It is the head of delusion. It is called aham, Brahma’s imagination of himself, his self-image or ego. The fifth head of Brahma declares Brahma as the lord and master of Prakriti. This claim over nature is humanity’s greatest delusion.

Hoping to shatter this delusion, Shiva uses his sharp nail and wrenches off the fifth head of Brahma. He becomes Kapalika, the skull bearer. Shiva severs the head that deludes Brahma into believing he created objective reality or Prakriti, when in fact, he has only created his own subjective reality, the Brahmanda.

Prakriti is nature. Brahmanda is culture. Prakriti creates man. Man creates Brahmanda. Prakriti is objective reality. Brahmanda is subjective reality. Atma witnesses Prakriti, aham constructs Brahmanda.

Kala Bhairava images from temple walls of North India

Every human being has his own cerebrum, hence is subject to his own imagination of his self and the world around him, which is why every human being imagines himself to be special. Every human being is thus Brahma, creator of his own Brahmanda. Prakriti is common to all living creatures but Brahmanda is unique to a Brahma. As many Brahmas, as many imaginations, as many Brahmandas.

Prakriti is the universal mother of all Brahmas. Brahmanda is, however, daughter of the particular Brahma who creates her. Nature does not consider any Brahma special. Every Brahma believes he is special in his own self-constructed subjective reality.

Every human being compares his subjective reality with nature and finds nature inadequate. This dissatisfaction provides an opportunity to outgrow dependence on nature, hence fear. But instead of looking inwards, Brahma looks outwards. Rather than take control of his mind, he chooses to take control of nature. He proceeds to domesticate the world around him. Every Brahma creates Brahmanda for his own pleasure or bhoga, indifferent to the impact it has on others. This self-indulgent act is described in narratives as Brahma pursuing his own daughter. By equating it with incest, a taboo in human society, the scriptures express their disdain for the pursuit of aham over atma, bhoga over yoga.

The story of Brahma chasing his daughter is taken literally to explain why Brahma is not worshipped. Metaphorically, it refers to the inappropriate relationship of humanity and nature. Rather than pursuing atma and becoming independent of nature, man chooses to pursue aham and dominate nature. This does not allay fear, it only amplifies fear.

Shiva mocks Brahma’s delusion by always appearing in a state of intoxication. He is always shown drinking or smoking narcotic hemp. In intoxication, one refuses to accept reality and assumes oneself to be the master of the world. When the reference point is aham, not atma, when the world is only Brahmanda not Prakriti, one is as deluded as one who is intoxicated.

Tantrik miniature painting of Gora Bhairava and Kala Bhairava

Brahmanda creates artificial value. In Brahmanda, we are either heroes or victims who matter. In Prakriti, however, we are just another species of animal who need nourishment and security and who will eventually die.

Realisation of this truth creates angst. Brahma wonders what is the point of existence then. He finds no answer and a sense of invalidation creeps in. It makes him restless and anxious. A life with imagination but no meaning is frightening. The human mind cannot accept this and so goes into denial. It seeks activities that fill the empty void created by time. It seeks to occupy the mind with meaningless activity so that it is distracted from facing the emptiness of existence. That is why human beings get obsessed with games and recreational activities that enable time to pass.

Shiva recognises this and so holds a damaru in his hand. A damaru is a rattle-drum that is used to distract and train a monkey. The monkey here represents the mind which is restless and angst-ridden. Unable to find meaning, it yearns to be occupied. Shiva rattles the drum to comfort Brahma’s mind. He hopes that, eventually, Brahma will realise that meaning will only come by moving towards atma rather than aham, pursuing yoga instead of bhoga, choosing Prakriti not Brahmanda.

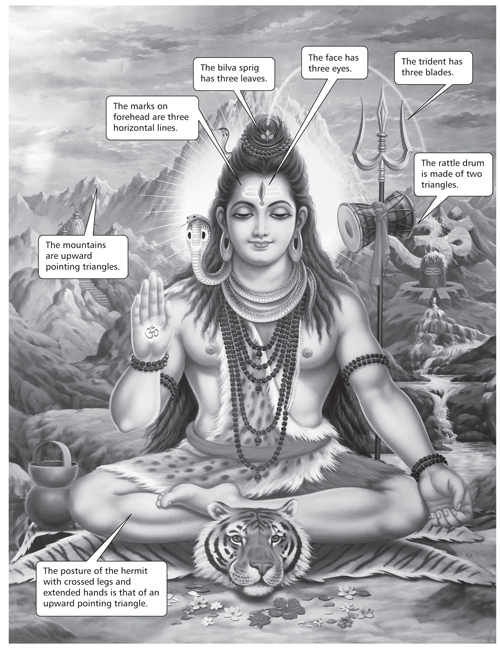

Recurring theme of three visible in poster images of Shiva

But Brahma stubbornly refuses to take the journey towards Purusha. He is determined to find identity and meaning through Prakriti alone. Brahma divides subjective reality into two parts: what belongs to him and what does not belong to him. Property is thus created. It is humankind’s greatest delusion through which humanity seeks to generate meaning and identity.

Animals have territory but humans create property. Territory is held on to by brute force and cunning; it cannot be inherited; it enables animals to survive. Property, on the other hand, is created by man-made rules; take away the rules and there is no property. Rules also govern relationships in culture, creating families to whom property can be bequeathed. Neither wealth nor family is a natural phenomenon, both are cultural constructions, hence need to be codified and enforced through courts.

Through the idea of property Brahma hopes to outsmart Yama. A human being can die but his property and his family can outlive him.

Brahma splits Brahmanda into three parts: me, mine and what is not mine. This is Tripura, the three worlds. Each of these three worlds is mortal. The ‘me’ is made up of the mind and body. ‘Mine’ is made up of property, knowledge, family and status. ‘Not mine’ is made up of all the other things that exist in the world over which one has no authority. Even animals have a ‘me’ but only humans have ‘mine’ and ‘not mine’. Human self-image is thus expanded beyond the body and includes possessions.

South Indian painting of Shiva as Tripurantaka, destroying three cities

Humans identify themselves with other things beside their body, hence get hurt when those things get attacked. A man derives his self-worth from his looks and his car. When his looks go, or his car gets damaged, his tranquillity is lost. Tranquillity is also lost when he yearns for things that are not his, things that belong to others. Anxiety and restlessness thus have roots in the notions of ‘mine’ and ‘not mine’, which depends on imagination for their survival.

At every Hindu ritual, ‘Shanti, shanti, shanti,’ is chanted. This means peace thrice over. Humans yearn to come to terms with the three worlds. This can only happen when we recognise the true nature of the three worlds we have created. Realisation of the true nature of Tripura will unfortunately reveal their mortal nature and the futility of clinging to them. Shiva is Tripurantaka, who reveals this reality and hence destroys Tripura.

The story goes that three demons created three flying cities and spread havoc in the cosmos. So the gods called upon Shiva to destroy these cities. The cities could be destroyed only with a single arrow. And so one had to wait for the right moment when the three cities were perfectly aligned in a straight line. Shiva decided to chase the three cities until this moment arrived.

The earth was Shiva’s chariot; the sun and moon were its wheels; the four Vedas were its horses; Brahma himself was the charioteer. Mount Meru, axis of space, was the shaft of Shiva’s bow while Sesha, the serpent of time, was the string. Vishnu was the arrow.

Shiva chased the three cities and waited for the moment when the cities were aligned. At that moment, he released the arrow and destroyed all three cities in an instant. He collected the ashes of these cities and smeared them across his forehead as three parallel lines. This was the Tripundra, the sacred mark of Shiva. It communicated to the world that the body, the property and the rest of nature, the three worlds created by Brahma, are mortal. When they are destroyed, what remains is Purusha, the soul.

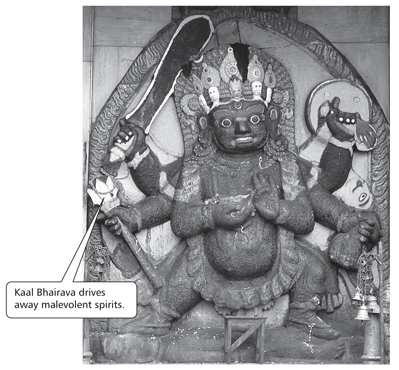

The fearsome Bhairava who protects Nepal

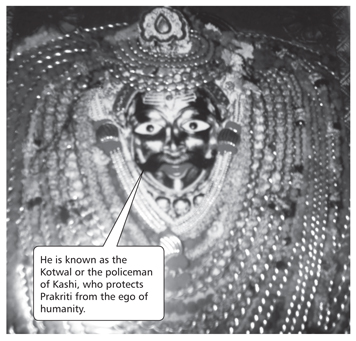

Kaal Bhairava of Varanasi

The lines are drawn horizontally. In mythic art, vertical lines associated with Vishnu represent activity, while horizontal lines represent inertia. Shiva’s mark is horizontal to remind us that nothing needs to be done actively to destroy the three worlds. Eventually, inevitably, the body will die, the property will go and the divide between ‘mine’ and ‘not mine’ will collapse as Prakriti stakes her claim. Shiva has infinite patience, which is why he is able to wait for the moment when the three cities align themselves, ready to be struck down by his arrow.

The number three plays a key role in Shiva’s mythology. His sacred mark is composed of three parallel lines. He holds in his hand a trident, a weapon with three blades. He is offered in temples the sacred bilva leaf which is a sprig with three leaves. Shiva holds the shaft of the trident just as the devotee holds the stem of the bilva sprig. What is held is the immortal soul; the three blades and the three leaves represent the three worlds that Brahma creates and values, which need to be given up if one seeks, ‘Shanti, shanti, shanti.’

Bhairava or Hara, the remover of fear, is visualised as a child riding a dog and holding a human head in his hand. The childlike form of Bhairava is to draw attention to his innocence and purity. There is no guile behind his actions. The head that he holds in his hand is the fifth head of Brahma, which is full of amplified fear and has no faith. This fifth head constructs the self-image. This fifth head constructs Tripura which Shiva destroys. The dog that Bhairava rides represents the human mind and how it regresses to animal nature when governed by fear.

Southeast-Asian image of Bhairava

Symbolically speaking, dogs are considered inauspicious in Hinduism. Dogs are most attached to their masters: wagging their tail when they get approval and attention, and whining when they do not. This makes the dog the symbol of the ego. Like the dog, aham blooms when praised and given attention and it withers when ignored. Ego or ahamkara has no independent existence of its own but is constructed by Brahma and dependent on Brahmanda in an attempt to outgrow fear. It ends up amplifying fear.

Dogs also remind us of the notion of territory. Dogs spray urine to mark their territory; even when they are domesticated and provided for, they mark territory indicating their lack of faith. They bark and bite to defend their territory. They fight over bones with other dogs. While dogs do it for their survival, humans behave similarly as they fight over their property and defend their rights. Humans seek the survival not of their bodies, as in the case of animals, but of their self-image, which is a combination of body and property. Property includes not just wealth, but also family and status. Without property there is no meaning, without meaning there is only fear.

Bhairava rides the dog to remind us of our animal instincts and our amplified fears that have constructed the notion of property. Like dogs we cling to ‘me’ and ‘mine’ and are wary of what is ‘not mine’. We call this love, but it is in fact attachment as they give us identity and meaning. Bhairava invites us to break this attachment, cut the fifth head of Brahma, cleanse the mind of all corruption, and discover the world where there is genuine freedom from fear.

Poster art of Datta, the gentle form of Bhairava

Many followers of Shiva worship Bhairava in a gentler form, as Datta, the three-headed sage who has four dogs around him and a cow behind him. Datta is called Adi-nath, the primal teacher of all mendicants.

Datta’s three heads represent Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva, who constantly create, sustain and destroy. The future is created, the present is sustained and the past is destroyed. Datta does not cling to any construction. He does not fear any destruction.

His four dogs are a reminder of our fears. The cow reminds us of our faith. The cow walks behind Datta; he does not turn around to check if she is following him. He knows she is. The dogs are our fears walking in front of Datta, constantly turning back to see if he is behind them. They do not have faith. They constantly need reassurance.

Datta wanders freely without a care in the world. Nothing fetters him. No property binds him. Having achieved the full potential of his human brain, he has outgrown fear. He trusts nature. Prakriti, visualised as the headless female body, who is Bhairavi, for the frightened Brahma, ends up as his companion, his friend, his mother, sister and daughter. He is at peace with the world.