2

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

Although the fanciful notion of a wily, skilled counterfeiter attempting to outwit the government may have some perverse romantic appeal, counterfeiting is a serious crime. It hurts the people who receive bogus currency and society as a whole. Anyone who innocently accepts fake money bears the financial loss. There is no compensation.1 Most at risk are the unwary, the careless, the illiterate, and the uninformed. And if the receiver knowingly attempts to pass on the counterfeit, he, too, commits a criminal offence. More generally, counterfeiting undermines money’s roles as a store of value and as the medium of exchange in the payment for goods and services. If counterfeiting reaches serious proportions and people lose confidence in money, day-to-day commercial and financial transactions could be seriously affected.

THE MAN WHO TRUSTED THE U.S. POST OFFICE

Counterfeiting can have an immediate personal cost. Just ask David Lipin. In May 2010, Lipin cashed a Postal Service money order for $1,000 at a post office in West Hollywood, California. He received ten $20 bills and eight $100 bills.

He then went to a nearby gas station, filled his car’s tank, and paid with one of his $100 notes. After looking at the bill closely, the clerk informed him that it was a fake. She then checked all his other $100 bills and said that she thought they were all counterfeits. She called the police. Panicked, the 43-year-old Lipin called a friend who was a lawyer and, following his advice, called the police himself and reported the counterfeits. Terrified that he would be seen as trying to pass bogus notes, he wanted to make it very clear that he was a victim.

When the police arrived and examined the notes, they told him that they were $5 bills that had been bleached and altered. When the bills were held up to the light, Lincoln’s face, which appears on the US$5 notes, was clearly visible behind the head of Benjamin Franklin whose face graces the $100 bill. And yes, all eight bills were counterfeits.

Back at the post office, an official said that although Lipin had a receipt showing that he’d cashed a money order there, there was no way to verify that he had been given the bills there. He could have received them after he left. The U.S. Secret Service was more sympathetic but ultimately told him there was nothing to be done. The post office is a business like any other, they said. If they were not in on the fraud, they are not responsible. Unless the perpetrator who’d forged the notes could be tracked down, there was nothing to be done. “Counterfeit money is like a hot potato,” said the deputy special agent in charge of the Secret Service’s L.A. office. “Whoever ends up with it last is the victim.”2

In his magisterial History of England, Lord Macaulay noted that “counterfeiting and the mutilation of the money of the realm [clipping]” became so widespread during the late seventeenth century that by “the autumn of 1695 it could hardly be said that the country possessed, for any practical purposes, any measure of the value of commodities. It was by mere chance whether what was called a shilling [twelve pence] was really ten pence, six pence, or a groat [four pence].” Indeed, he “doubted whether all the misery which had been inflicted on the English nation by bad Kings, bad Ministers, bad Parliaments, and bad Judges was equal to the misery caused in a single year by bad crowns [five shillings] and bad shillings.” He added that “when the great instrument of exchange became thoroughly deranged, all trade, all industry, were smitten as with a palsy. . . . Nothing could be purchased without dispute. . . . On a fair day or a market day, the clamours, the reproaches, the taunts, the curses, were incessant: and it was well if no booth was overturned and no head broken.”3

Given the many payment alternatives available today, it’s hard to imagine that counterfeiting could seriously undermine the efficient operation of the modern global economy. However, without the vigilance of law enforcement agencies and the continuous efforts of the issuers to stay at least one step ahead of counterfeiters, bogus payment instruments could seriously disrupt day-to-day commerce. Today, not only bank notes and coins issued by central banks and mints are at risk. Cheques, debit cards, credit cards, and even electronic money are all subject to counterfeiting. No means of payment is immune to unauthorized duplication.

The losses to individuals and society from those counterfeits that make it into circulation are not the only costs. Counterfeiters steal the profits that the issuer of the currency would have made from the printing or coining of money. These profits reflect the difference between the cost of producing the coin or note and its face value. For example, it costs less than twenty cents to produce a $100 bill.4 Counterfeiting could also undermine monetary policy through a possible loss of confidence in a country’s currency and in its central bank as an effective monetary institution. John Cooley, in his book Currency Wars, which charts episodes of state-sponsored counterfeiting over modern history, argues that counterfeiting is the “new weapon of mass destruction.”5

The costs of fighting counterfeiting are also considerable, typically many times the direct losses.6 Businesses must train staff on how to identify counterfeits and how to use counterfeit detectors. Should individuals or merchants lose confidence in a particular denomination, or, worse, lose confidence in the national currency, they will suffer the inconvenience of using other less convenient denominations, a foreign currency, or other payment instruments. Central banks also bear the cost of printing new notes with additional security features and withdrawing less secure note issues, while police and the judicial system must bear the cost of investigating, capturing, and prosecuting suspected counterfeiters.

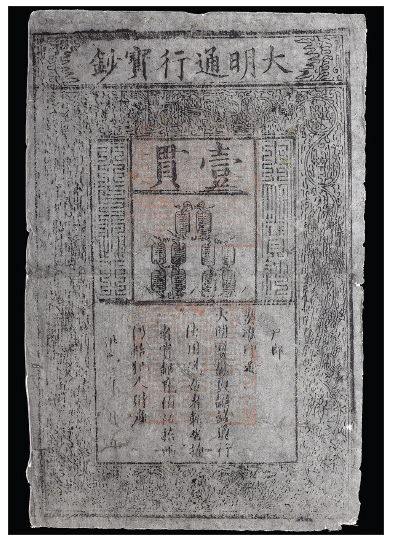

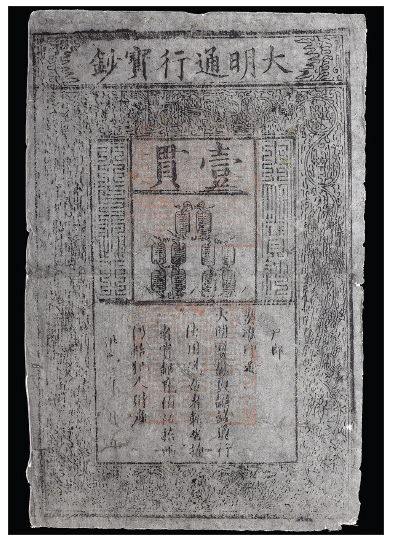

China, Ming Dynasty, 1 kwan, 1368–1644. The bottom section of this note translates as, “This Ta Ming Pao Cha’o [Great Ming note] is printed with the approval of the the Emperor . . . and used side by side with the copper cash. Those who counterfeit Ta Ming Pao Cha’o will be beheaded, while the informant will be rewarded with 250 taels of silver [about 300 ounces] with confiscated property of the convict into the bargain.”

(National Currency Collection)

The penalties for counterfeiting and for passing bogus currency have always been severe, reflecting its potential destructive effects and, historically, the notion that counterfeiting was a form of treason, since it usurped an activity traditionally reserved for the sovereign. Indeed, the word “seigniorage,” used to describe the profits derived from minting coins or printing notes, comes from “belonging to the seigneur,” a feudal lord. Counterfeiting was therefore seen as a treasonous attack on the Crown’s prerogatives and, until the nineteenth century, was a capital offence in Canada. It remains so in parts of the world even today.

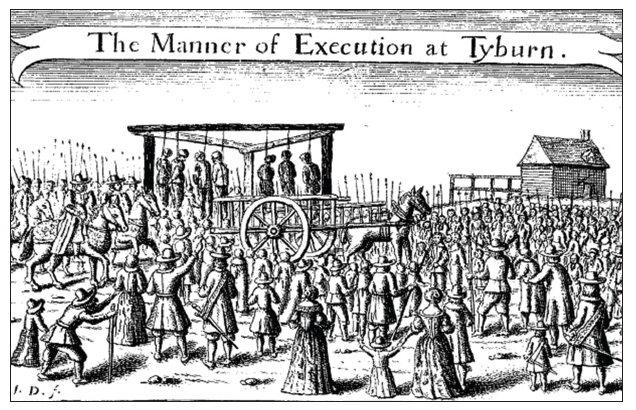

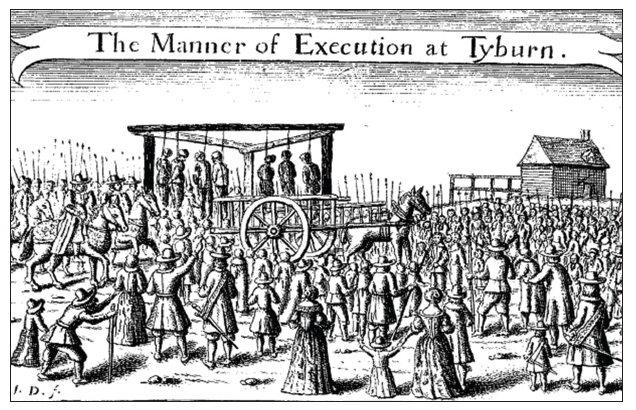

The notorious Tyburn Tree was the site of mass hangings for almost 600 years, until 1783 when executions were moved to the Newgate Prison. Thousands of spectators would gather to watch the weekly spectacle on the huge wooden triangle that could hold up to twenty-four bodies. The site is said to be located at what is now Marble Arch at the northeast corner of Hyde Park.

(Artist unknown, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Manner_of_Execution_at_Tyburn.jpg)

To further deter counterfeiting, the modes of punishment were frequently gruesome. During Roman times, they included the removal of ears or nose and castration, as well as the loss of Roman citizenship. Counterfeiters were sometimes burned alive or fed to the lions in the arena.7 Death was also the punishment for counterfeiting bank notes in China, where paper money was first introduced.8

In France, during the reign of Francis I in the early sixteenth century, counterfeiters were boiled alive in a cauldron of water.9 During the French Revolution, the guillotine became the preferred method of execution. Jean-Marie Keratry, ex-count and former officer of the gendarmerie, was guillotined for falsifying assignats (the revolutionary currency) on 27 Thermidor, year 2 of the Revolution (14 August 1794).10 In medieval times, counterfeiters were boiled alive in oil in Germany, while in Russia, molten lead was poured down their throats.11

In England, after the Norman Conquest in 1066, counterfeiters could expect to have their hands cut off and their eyes gouged out, in addition to being castrated.12 In the fourteenth century, during the reign of Edward III, Ralph Marshall, the Abbot of Missenden, convicted of coining and clipping, was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. Fortunately for the Abbot, he received the King’s pardon.13

As late as the eighteenth century, women were burned at the stake for counterfeiting, while the penalty for men was hanging. The last woman burned at the stake in Britain was Catherine Murphy, executed on 18 March 1789 for “colouring a piece of metal to resemble a shilling.” Prior to being burned, Murphy was strangled “by the humanity of the sheriff.”14 The following year, burning was abolished and replaced by hanging.

Despite such appalling penalties, the profits from counterfeiting and clipping coins were so large that forgers were willing to run the risk. Lord Macaulay writes:

It was to no purpose that the rigorous laws against coining and clipping were rigorously executed. At every session that was held at the Old Bailey [London law court] terrible examples were made. Hurdles, with four, five, six wretches convicted of counterfeiting or mutilating the money of the realm, were dragged month after month up Holborn Hill. One morning seven men were hanged and a woman burned for clipping. But all was in vain. The gains were such as to lawless spirits seemed more than proportionate to the risks.15

At the end of the seventeenth century, currency reform in England, led by Sir Isaac Newton, prompted the replacement of hammered coins that were easily clipped by more secure milled coins. The penal code was also strengthened, making it illegal for a person to have silver filings or parings in his possession on the presumption that they came from clipped coins. Those convicted were branded on the cheek with a red-hot iron. If bullion was found, it was up to the accused to prove his innocence. Informers received large rewards: clippers who turned in two other clippers received a pardon.16 Convicted counterfeiters and clippers continued to be hanged.

SIR ISAAC NEWTON: DETECTIVE

On the morning of 22 March 1699, one of England’s most notorious and talented counterfeiters met his end, twitching at the end of the hangman’s rope at Tyburn. His name was William Chaloner, and the man who finally sent him to the executioner was none other than mathematician and physicist Isaac Newton.

Having become an international figure after publication of his Principia, Newton was attracted to the idea of living in the exciting and cosmopolitan world of London rather than the quiet academic environs of Cambridge. Thus, when offered the position of Warden of the Royal Mint, a position seen as a sinecure involving a hefty paycheque and little effort, he readily accepted. The timing was unfortunate, however. England’s silver coinage had been debased to about half its legal weight, and the hand-struck, non-standard coins produced by the mint were an open invitation to clippers and counterfeiters. The Mint was in the process of recalling and recoining the entire stock of silver coins, in addition to tracking down and prosecuting forgers. Pursuing criminals was not what Newton thought he had signed on for, and he complained to the Treasury, asking whether he could be relieved of the task. When told that he could not, he tackled the challenge with the same deliberation and diligence that he brought to any problem.

While most counterfeiters proved easy marks for Newton’s investigations, William Chaloner, the most skillful and notorious, also proved to be the most challenging.

Born into poverty and apprenticed to a nail-maker in Birmingham, Chaloner quickly turned his skill with metal to forging silver “groats,” worth about four pennies. But Chaloner’s ambition soon drew him to London. Finding it hard to break into the tight criminal underworld, his early scams included collecting rewards by informing on schemes that he had set up himself. He soon managed to put his previous talents to use, however, learning the art of gilding and producing quantities of bogus gold and silver coins. By his own admission, he counterfeited about 30,000 pounds worth of currency over seven or eight years, an enormous fortune at the time.17 His wealth allowed him to pose as a gentleman, even writing papers on how to fight coining. The two adversaries first met face to face when Newton interrogated Chaloner about the theft of dies from the Mint—a dreadful scandal. Newton never tracked them down, but Chaloner’s growing arrogance soon proved to be his undoing.

Chaloner went after Newton directly, publishing a pamphlet and appearing before Parliament, accusing him of incompetence and corruption in his management of the recoinage of silver. Newton was incensed and instigated an extraordinary investigation, using methods worthy of any modern police force. He set up nets of undercover agents and informers in London’s worst neighbourhoods. He interrogated suspects in the Tower and carefully built a web around Chaloner. Chaloner, meanwhile, had discovered the advantages of the new paper instruments being tried by banks. He needed only paper and ink to fake the Malt Lottery Tickets that were his last creation. But he had hardly finished the print run when he was arrested and thrown in jail. He had a series of cellmates, all of whom proved to be Newton’s plants.

Chaloner’s trial took less than an hour. He was found guilty of high treason. The volume and precision of evidence amassed by Newton over two years was undeniable. The condemned man wrote to Newton begging for mercy. Newton did not respond.

Great Britain, £1, 1805. During the Napoleonic Wars, the Bank of England suspended payments in coin and issued poorly printed paper notes in low denominations.

(National Currency Collection)

The introduction of paper money at the end of the seventeenth century led to new concerns about counterfeiting. In 1696, it became a capital offence to forge or tamper with the bank notes issued by the newly established Bank of England.18 Forgers were slow to take advantage of their new opportunities for personal gain. The first known counterfeit Bank of England note did not surface for more than fifty years. It was made by Richard Vaughn, a Stafford linen draper.19 But so much publicity was given to the fraud and to the apparent ease of forging Bank of England notes, that counterfeiting subsequently became commonplace.20 In 1773, the illegal reproduction of the Bank of England’s watermark was made punishable by death. Lesser penalties were awarded for using the words “Bank of England” on any unauthorized engraved bill or for making a promissory note that resembled a Bank of England note.21

Aversion to the widespread use of the death penalty for property offences, including counterfeiting, began to emerge in Great Britain in the early nineteenth century. During the Napoleonic Wars, gold was in short supply, causing the Bank of England to suspend the convertibility of its notes, notwithstanding its promise “to pay the bearer on demand.” As gold sovereigns disappeared from circulation, the Bank issued small-denomination notes, which were widely used, especially by the poor. But the one- and two-pound notes were so badly printed that they almost invited illegal reproduction. In addition, many considered genuine notes to be as deceptive and fraudulent as the counterfeits, owing to their lack of convertibility. An 1856 article in The Economist recalled events during the early part of the century:

It is not long since . . . that three or four human beings were strung up weekly at Newgate, and were seen swinging in the breeze. Twenty or thirty persons were then sentenced to death at a time for issuing a bad half-crown or a forged one-pound note. The practical lesson taught by the process was, that man, for some or any purpose, such as preventing ill-executed coins or inconvertible bank notes, which carried in their denominations or their false promises incontestable evidence of a disregard in those who coined or issued them of the right of property, from being imitated, might take away life. It was a specific encouragement to murder. It proclaimed to all the expediency of killing to secure a presumed advantage.22

The poor quality of bank notes, the severity of the law, and the disproportionate burden of the death penalty borne by the poor led to a call for reform.

[T]he severity of that part of our penal code which awarded the punishment of death for forging or uttering forged notes, together with the defective nature of the paper, and the facility with which it was imitated, attracted the attention of scientific and benevolent men, who endeavoured, by writing and by declamation, to procure either an alteration of the law or an improvement in the note.23

A new philosophy regarding the correction of malefactors also gained support. In his 1848 history of the Bank of England, John Francis writes, “We have found out that to prevent a crime is better than to punish it; we have discovered too, and it has penetrated our commercial hearts, that it will cost less to teach a man to be good than to punish him for being bad.”24 In 1830, following the circulation of a petition signed by leading British financiers, a bill was submitted to Parliament to repeal the death penalty for counterfeiting and other property-related crimes. It became law in 1832. Counterfeiting became a felony punishable by transportation “beyond the seas” for seven years to life. Imprisonment from two to four years was prescribed for lesser currency-related offences.25

In North America, severe penalties were also meted out to counterfeiters in both the French and English colonies. The card money introduced in New France in 1685 to alleviate a gold shortage was an easy target for counterfeiters. Penalties for counterfeiting it ranged from flogging to banishment, or even hanging. In 1690, Pierre Malidor, a surgeon, was found guilty of counterfeiting and passing card money. His punishment was to be “beaten and flogged on the naked shoulders by the King’s executioner, at the gate of the Parish Church of Notre Dame in this town [Quebec City], and in the customary squares and places, in each of which he shall receive six lashes of the whip, furthermore to make good the value of the said cards forged by him, and to pay to the King a fine of ten livres.” Malidor was also condemned to compulsory military service for three years, was banished at least sixty leagues from Quebec City, and was forbidden to return on pain of death.26

Cartoonist George Cruikshank claimed to have sketched this satirical protest “note” in ten minutes in 1819 after seeing a woman hanged for passing a bogus note. The features of a regular Bank of England note are replaced with gruesome images of skulls, a noose, hanging bodies, and a horrifying Britannia gobbling her children. “J. Ketch,” signatory of the note was a catchphrase for the hangman.

(©Trustees of the British Museum)

In 1730, François Pelletier and several accomplices were also convicted of being faux monnoyeurs. Pelletier was “put to the test ordinary and extraordinary” (i.e., tortured) during the investigation. He was subsequently fined fifty livres, his property was confiscated, and he was banished “either for the West Indies or for old France.”27

Given the rewards of counterfeiting card money, however, banishment was insufficient, leading to the introduction of capital punishment for the crime. Louis Mallet and his wife, Mary Moore, who lived in the Parish of St. Laurent on the Île d’Orléans, were hanged on 25 September 1736 for making and circulating bogus card money.28

But the death penalty was not consistently applied. In 1748, François Bigot, the newly appointed Intendant of New France, complained that “intrigues” led to judges saving the criminal, that banishment to the West Indies or France had made “no impression,” and that counterfeit card money passed daily. He looked to France for assistance, and in a subsequent despatch to Bigot, the minister in Paris promised to consult with the King on the enforcement of the death penalty.29

WANTED

All persons of whatever quality or condition they may be, who may have knowledge of the whereabouts of one Le Beau, short in stature, wearing a brown wig, face pock-marked, eyes black and small, and a little sunken, stammers slightly, are ordered to notify us, or even to arrest him, we promising those who bring him to us the sum of 300 livres, in addition to the expenses they have incurred in bringing him. We forbid all persons to conceal the said Le Beau or to give him shelter on pain of being prosecuted as an accessory to the crime of counterfeiting, of which Le Beau is accused.

Done and issued at Quebec, November 14, 1730, Signed Charles, Marquis de Beauharnois, Knight of the military order of St. Louis, and Lieutenant General in New France and Gilles Hocquart, Knight, Councillor of the King in his Councils, Commissary General of the Marine, Director performing the functions of the Intendant of New France.30

Under the 1774 Quebec Act, Quebec retained the French civil code following the British conquest of New France, but British criminal law replaced French criminal law. Reflecting prevailing British practices, the counterfeiting of gold and silver coins remained a capital crime. The counterfeiting of copper coins was considered only a misdemeanour, however, punishable by up to two years in prison.31

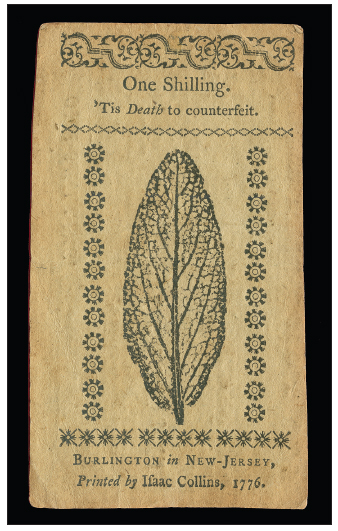

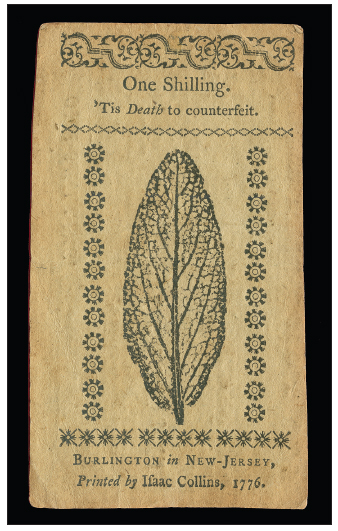

In the English colonies of North America, posted penalties were also harsh. Bank notes in colonial America were often stamped with the warning “’Tis Death to Counterfeit!” It appears that few counterfeiters suffered that fate, however, owing to difficulties in securing convictions, partly because the British government did not recognize colonial paper money as legal tender.32 In the early nineteenth century in Nova Scotia, convicted counterfeiters of Treasury notes were set in the pillory “with one ear nailed thereto,” followed by a public whipping through the streets of the town where the offence occurred.33

Passing counterfeit coin was treated relatively leniently. In 1753, David Dodge of Massachusetts Bay was charged with importing and uttering false “Double Loons otherwise called four pistoles pieces” in Halifax.

Not having the Fear of God before his Eyes nor Weighing the Duty of his Allegiance but being moved and Seduced by the Instigation of the Devill and contriveing and Intending our said Lord the King and all his people in this province craftily Falsely Deceitfully in order to Deceive and Defraud on or about the first day of January in the Twenty sixth year of the Reign of our sovereign Lord George the Second now King of Great Brittain & did unlawfully and Deceitfully bring into this province being part of the Dominions of the Realm of England from parts beyond the Sea Certain pieces of false and Counterfeit Coins of money of Pewter, Lead, Tin, Brass or other mixt metals to the Likeness and similitude of the good and legal and current money and Gold Coin of our said Lord the King of the province.34

Found guilty, Dodge received a sentence of only six months in jail. He was also required to find “sufficient Securitys for his good Behaviour.”

In 1785, Stephen Burroughs, an infamous con man in colonial America, was found guilty of passing counterfeit coin in Massachusetts. He received one hour in the pillory and three years in prison. That same year, a glazier named Wheeler received one hour in the pillory, three years in prison, and twenty stripes for making counterfeit coins. His ears were also cropped.35

In Upper and Lower Canada, there was no explicit prohibition against counterfeiting foreign bank notes during the early 1800s. Consequently, the Canadian border regions became a haven for U.S. counterfeiters who exported their product to the major commercial centres in New England. In 1810, after a request from the governor of Vermont, the legislature of Lower Canada made the counterfeiting of foreign bank notes a crime, albeit a non-capital felony.36 (See chapter 5, “One Great Holiday.”) The legislature of Upper Canada subsequently followed suit. Upon the issuance of the first Canadian bank notes by the Bank of Montreal, which received its operating charter in 1822, it became a capital offence to counterfeit the bank notes and other promissory notes of Canadian banks. The penalty for possessing engraving plates or counterfeiting tools was also death without benefit of clergy.37

New Jersey, 1 Shilling, 1776. Early colonial notes made it clear that counterfeiting was a capital crime.

(National Currency Collection)

Penal reform in Great Britain during the 1830s, which sharply reduced the number of capital crimes in that country, influenced events in Canada. By 1847, the penalty for counterfeiting domestic or foreign bank notes and passing them had been reduced to a prison sentence of up to seven years with hard labour.38 In 1849, the first offence for counterfeiting coin was considered a misdemeanour subject to a prison term of up to four years at hard labour. A second offence was considered a felony and was therefore subject to harsher punishment.39 In 1853, revisions to the Currency Act stiffened the penalties for counterfeiting and uttering (passing) bogus coin, with the first offence drawing a prison term of at least three years but no more than fourteen years at hard labour, and a second offence punishable by fourteen years to life imprisonment.40

Under Canada’s Criminal Code of 1892, persons convicted of counterfeiting domestic or foreign bank notes were subject to life imprisonment, while the possession and uttering of forged bank notes drew a penalty of fourteen years in jail. The making of counterfeit gold and silver coins also drew a punishment of life imprisonment, while the clipping of gold and silver coins was subject to fourteen years in jail. The possession of bogus coins was subject to three years in jail.41

Under the current Criminal Code of Canada, the making, possession, and uttering of counterfeit bank notes or coins all earn prison terms of up to fourteen years. In order to maintain confidence in the currency and to protect the economy from the significant effects of counterfeiting, “the courts have recognized the importance of deterrence, both general and specific, and denunciation as significant sentencing principles in addressing counterfeiting offences.”42

In addition, case law suggests that courts typically treat the making of counterfeit money more severely than its distribution or possession. Also, the more realistic the fake notes look, the stiffer the punishment will be, on the grounds that making realistic notes requires significant planning. These types of notes are more likely to fool people, and therefore pose a greater risk to society. The quantity of notes produced is an additional factor in sentencing as is the sophistication of the counterfeiting. Voluntary restitution by the perpetrators can be a mitigating factor.43

ENDNOTES FOR CHAPTER TWO