(The Globe, 15 June 1880)

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a number of celebrated counterfeiting gangs operated in Canada. They typically involved families—often several generations. Given the scale of their operations, many people were required to engrave, print, and distribute the bogus notes. With little honour among thieves, keeping the business in the family was one way of ensuring against snitches and infiltration by the authorities.

In the 1860s, the Johnson clan set up operations in Ontario after having fled the United States. Already notorious south of the border, the family was a major source of counterfeit bank notes, both American and Canadian, for almost thirty years. At the turn of the twentieth century, Anthony Decker, dubbed “one of the most dangerous men in Canada and the United States” by The Globe newspaper in June 1904, was a talented professional engraver and head of another family counterfeiting ring. Active in southern Ontario, the Decker family plagued area businesses with excellent counterfeits of Dominion and chartered bank notes. Twenty years later, the Beaudoin family of l’Assomption, Quebec, was busted in the biggest counterfeiting seizure of the age.

The detective had been following the old man for some time, hoping that he would slip up. Each time the dapper old gentleman made a purchase, the detective would quickly ask for the bills he’d paid with and check them. Finally, the man purchased a necktie at a haberdashery in Markham and paid with a counterfeit bank note. The detective followed him onto the train back to Yorkville, and when he stepped off, tapped him on the shoulder.

“Good evening, Mr. Johnson,” said the detective.

“You have the advantage of me,” replied the old man, “Who might you be?”

“I am Detective John Wilson Murray, and you, sir, are my prisoner.”1

And so, in June 1880, after a two-year search in the United States and Canada, Ontario’s first full-time criminal detective arrested seventy-five-year-old Edwin Johnson, solving what was famously known as “The Million Dollar Counterfeiting.”

Five years earlier, an expert at the Treasury Department in Washington had come across a beautifully engraved US$5 note—a note superior to any he had ever seen. When the serial number was checked, it was found to be counterfeit. Soon large numbers of Canadian counterfeits of equally high quality began to appear. Murray was put on the case and showed the notes to ex-counterfeiters in both countries. They agreed that such “masterpieces” had to be the work of Edwin Johnson. After years of fruitless searching, Murray spotted one of Johnson’s sons in a Toronto train station and followed him home to Yorkville, where he finally located Johnson senior.

Even in the York County jail, the old man insisted that his name was Anderson, but Murray was convinced that this was Johnson and told him that all he wanted was the plates he’d used to produce the notes. He gave the man some cigars, told the jailer to treat him well, and left. The next morning, “Anderson” said that he saw no way of “releasing himself from the snare into which he had fallen.”2 He told Murray that he was caught only because he’d had a drink and been careless, that he would otherwise never have passed a bogus note himself, and he agreed to take Murray and the police to the plates.

They travelled in a carriage west through Yorkville to Davenport Road and along it for about a mile, then up Wells Hill and into the woods. Johnson took them to a spot where the trees formed a triangle and told them to dig at the base of one of the trees. Having neglected to bring a shovel, they used sticks and, after a few fruitless hours, were convinced that they were being fooled. But the old man seemed genuinely disappointed at not having found anything and directed them to the foot of another tree. They soon struck a small oblong wooden box. Inside were twenty-one copper plates, three for each note: the Ontario Bank $10, the Canadian Bank of Commerce $5 and $10, the Bank of British North America $5, the Dominion Bank $4, the Dominion of Canada $1, and the $5 U.S. notes. Each set was carefully wrapped in oiled cloth and covered in beeswax. It was the largest number of counterfeit plates ever recovered in Canada or the United States. Johnson was returned to jail, and the plates left with the Attorney General.

(The Globe, 15 June 1880)

The man who nabbed the Johnsons. Murray’s portrait as it appears in his memoirs.

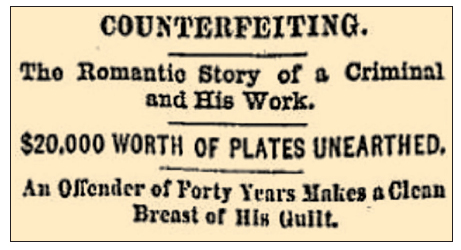

(National Currency Collection)

Johnson was proud of his engraving skills and proud of his five sons, Charles, Thomas, Edmund, David, and John, who were becoming adept at the craft.3 “One may soon be better than me,” he told the detective. His daughters, Georgina and Jessie, were expert at forging signatures, having been trained since childhood, and his wife supplied notes to wholesale dealers who placed them for “shoving.”

Ontario Bank $10, 1870. The quality of the counterfeit notes produced by the Johnsons was so good that the chartered banks hit were forced to change the designs of their notes. The Johnson forgery is the top note, with the authentic note below. The difference in the colour of the two notes may be the result of handling and wear of the Johnson counterfeit or might be from paper used by the forgers to make the note appear worn.

(National Currency Collection)

The Johnson family was a finely tuned counterfeiting machine, and had placed over $1,000,000 in counterfeit Canadian notes. Many of the finely engraved notes continued to circulate for years.

Edwin Johnson pleaded guilty when brought to trial. Because of his age and his co-operation, he was given a suspended sentence and was returned to the United States.

The Johnsons’ reputation as master counterfeiters went back more than thirty-five years in the United States. In 1864, members of the clan had been captured in Lawrence, Indiana, and charged with issuing and passing more than $100,000 in bogus U.S. greenbacks. To avoid prison, the Johnsons cut a deal, surrendering their plates and informing on other counterfeiters, thus eliminating a large part of the competition.4

The family had habitually moved between the United States and Canada as risk and opportunity dictated. Indeed, John Johnson had been arrested in Indianapolis a month before his father for passing counterfeit $5 U.S. notes. At his high-profile trial six months later, he provided an alibi and was acquitted. His brother Charley had not been so fortunate, having been arrested in New York in 1879 for issuing very fine bogus $5 notes carrying the portrait of Andrew Jackson. He was in prison until 1888, during which time his father, Edwin, and his brothers John and Tom died.

The old man’s prediction proved to be correct. His sons did indeed take over the family business. Tom and Charley had both become expert engravers, and over the next eighteen years (1880–98) the family produced $2 (Windom) and $5 (Hancock) U.S. silver certificates of such high quality that they passed undetected for years. Even when the counterfeits were identified, they were not linked to the Johnsons. Finally, in 1888, shortly after his release from prison, Charley was arrested for issuing counterfeit “Grant Head” $5 certificates, ten of which a Secret Service agent had purchased by mail for $22.50. He escaped from Detroit, where the family had been living quietly, and fled to Port Huron in Canada, where he was soon arrested for counterfeiting British Bank of North America $5 notes and Canadian Bank of Commerce $10 notes “believed to be the finest work of counterfeiting in the Dominion.”5

Charles was released from Kingston Penitentiary in 1898, the same year that John Wilkie was named Chief of the U.S. Secret Service. In order to track down the Grant Head plates, which had never been found, Wilkie decided to have Charles tailed when he returned home to Detroit. He would leave home in the middle of the night and frequently not return for a week or two. Convinced that he was engaged in some criminal pursuit, the detectives decided to raid two houses belonging to the family.

At the home of David Johnson and his wife Kate, they found counterfeit notes, engraving tools, copper plates, chemicals, and unfinished Windom notes concealed in panelled cupboards activated by switches hidden in the baseboard. David Johnson’s meticulous records showed that he travelled extensively throughout the country to pass bogus notes, mainly $2 and $5. On one trip to Ohio he passed $1,500 in 22 days—a record-breaking feat.

At the lavishly furnished, two-storey house on McGraw Avenue, where Charley had been living with his mother, his brother Edmund, and his sister Georgina Baylis, similar caches revealed $5,000 in bundled counterfeit notes, dies for applying serial numbers, and packages of unused bank-note paper. David, his wife, Edmund, and Mrs. Baylis were all arrested and charged.

In return for telling police the location—in Toronto—of the plates for the infamous 1891 Windom notes, the police agreed to let Johnson’s wife Kate go and to release Mrs. Baylis on $200 bail.

Just over a year later, police arrested a Cyrus Davis who turned out to be Charles Johnson. The last member of the famous family was behind bars. The plates for Charley’s $5 Grant notes were never found.

In 1899, excellent bogus $1 Dominion notes began to surface in Ottawa, Toronto, and Montreal. The case was taken up by Police Commissioner Sherwood, who soon traced the notes to Anthony Decker, an expert engraver employed by the British American Bank Note Company in Montreal and a man of seemingly impeccable reputation. Decker was fifty years old and had been with the company for just over three years, having come from Philadelphia. He was “a sober and steady worker with no bad habits, except that of smoking continually, which was overlooked because he worked in a certain class where few excelled.”6 One of his daughters was also employed by the bank-note company. Before any arrest could be made, however, Decker mysteriously disappeared.

Police continued to hunt for what they were now convinced was a gang. Decker returned to Montreal, but was warned by means of a newspaper ad that the police were looking for him. The “gang” scattered with police still dogging their tracks.

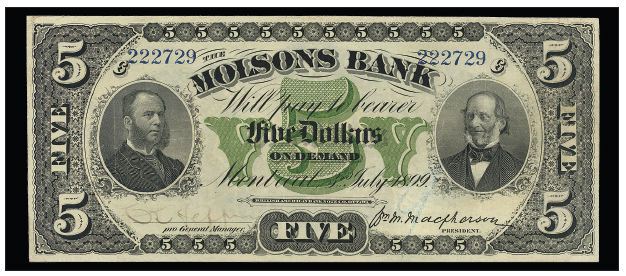

Anthony Decker was finally arrested in Baltimore with counterfeit bills in his possession, as well as the key to a unique cipher code that had been used to send messages among the group. His son Paul, alias Paul Rose, was arrested in Woodstock, Ontario. With him was an engraved plate for the back of a $5 Molson’s Bank note, as well as engraving tools, six cans of ink, and a printing press. Anthony Decker’s wife was picked up in Hamilton, where the police found a counterfeit plate for a $2 note. Their associate Hans Kunz was arrested in London, Ontario. He had bank-note paper and ink in his possession. Kunz had previously been a lithographer with the Ontario Printing and Lithographing Company.

None of the Molson’s Bank notes had been passed, since the plates were incomplete. The group had evidently planned to set up shop in Woodstock, producing the Molson’s Bank notes. Anthony and Paul Decker were convicted and sentenced to five years in Kingston Penitentiary, Kunz to fifteen months. Mrs. Decker, who had a heart condition, was eventually discharged after giving evidence against her husband and son.7

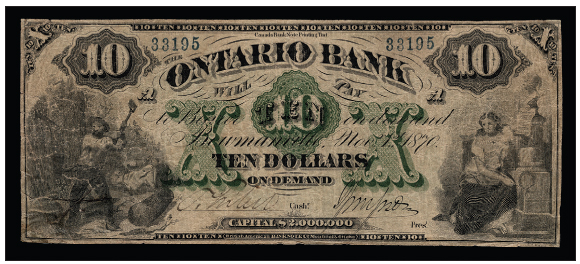

Dominion $1 note, 1898.

(National Currency Collection)

Molson’s Bank, $5, 1899.

(National Currency Collection)

Released from prison in 1904, Anthony Decker was placed under close surveillance by police. The authorities were convinced that while he was in the Kingston Penitentiary he had teamed up with Charles Higgins, a professional lithographer and counterfeiter. Two years earlier, Higgins had been convicted of passing $300 in counterfeit $5 Molson’s Bank notes in Toronto but was given a reduced sentence for revealing the location of fake plates for $2 Dominion notes. On June 27, as the result of a stakeout, police raided an office on the fourth floor of the Cornell building at the corner of Adelaide and Church streets in Toronto. Inside they found Charles Higgins in the process of rolling out the back prints of $2 Dominion of Canada notes in what appeared to be a first-class counterfeiting plant. The printing press weighed 600 pounds.

Disappointed at not finding Decker with Higgins, the police went to Decker’s rooms on Peter Street and found plates, engraving tools, and genuine notes from the Imperial Bank and Molson’s Bank that they believed were to be used as models. The plates had not been engraved, but paper found with them carried the same watermark as that used by Higgins. Although Decker’s landlady testified to seeing the two carrying a trunk up to Decker’s room, this was altogether very thin evidence.

Both men pleaded not guilty. Higgins claimed to have been hired by a mysterious Mr. Quigley who had set up the plant and asked him to print cards and invitations. He claimed that when he arrived to work he saw the stone with the impression of the notes on it and became angry, asking Quigley what he was up to. Quigley asked him if it was a good engraving job and then disappeared into the bathroom moments before the police charged in. Quigley was never found. There was some indication that he might have been one of the detectives, and that Higgins and Decker had been the victims of a police “sting” operation, but this was never proved.

The only other evidence was correspondence between Decker and Higgins. Decker had asked Higgins to find him a room in Toronto, and they had discussed lithographic techniques and recipes. They claimed this was because Decker was going to produce a book of maps. The Crown then brought counterfeiter Joseph Gentile from Kingston Penitentiary to testify that Higgins had written letters to him, outlining his plans to produce counterfeit notes. Higgins denied everything, claiming that he knew he was being followed as soon as he was released from prison and was determined to go straight. His case was helped by the tearful testimony of his wife who carried their year-old child in her arms.

Nevertheless, after three trials, Higgins was convicted of counterfeiting and given seven years. Decker was released on bail. In April 1905, Anthony Decker died from an overdose of paregoric that he regularly used as a sleeping draft.8

Police had failed to prove that he had ever been in Higgins’s room.

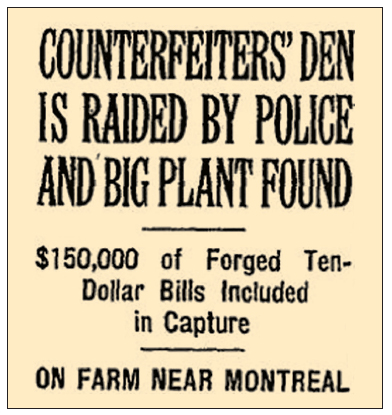

In the morning of 1 April 1925, a fifteen-member team of RCMP constables led by Staff-Sergeant Salt drove from Montreal to l’Assomption, Quebec, a small community northwest of the city, their target an isolated farmhouse located about three miles from the village. The police were acting on news of counterfeit $10 notes of the Banque Canadienne Nationale circulating in Trois-Rivières, with suspicion falling on the Beaudoin family, owners of the farmhouse.

The raid got off to a bad start. The weather was foul, alternating between rain, sleet, and wet snow, and the three police cars quickly got bogged down in mud even before leaving the city. Driving conditions deteriorated further after they crossed the Rivière des Prairies. Flooding had made the highway almost impassable. One of the police vehicles stalled and had to be towed the rest of the way.

But by about four a.m., the team had reached the farmhouse. Swooping in from the back and the front, the RCMP team caught its residents by surprise. This was no April Fool’s joke. Arrested were Joseph Beaudoin, aged sixty years; his five sons, Pierre Paul, J. Raphael Maximilien, Alfred, J. Isidore Mederic, and Gustave (also referred to as Jean), ranging in age from thirty-two to eighteen years; as well as Denis Viger, a friend of the family. The police were startled to find drying $10 bills papering virtually every surface in the house. The newly made bills, “which were laid out on the floors, tables, chairs and beds of the two large rooms, and which clung to the muddy boots of the Mounties when they rushed into the dark farmhouse, were all fair imitations of $10 bills of the Banque Canadienne Nationale.”9 In total, $150,000 in forged currency was seized, along with 500,000 paper blanks, cut to note size and ready for printing, as well as a modern printing press that could be operated by foot or by electricity. The accused were initially reluctant to hand over the plates used to make the bank notes. However, after police had a “very short discussion of a most persuasive nature” with Viger, the alleged maker of the plates, one of Beaudoin’s sons produced them. To add a note of pathos to the events, the wife of Joseph Beaudoin lay dying in an upstairs bedroom. Taking pity on Beaudoin senior, the police permitted him to stay by her bedside, while the rest of the accused were taken to RCMP headquarters in Montreal.

(The Globe, 2 April 1925)

Banque Canadienne Nationale, $10, 1925.

(National Currency Collection)

If anything, the return journey was more difficult and uncomfortable than the trip out. In addition to the team of fifteen police officers, the three automobiles were loaded with the six prisoners. The weather had also deteriorated with heavy snow and high winds. Once again, a car broke down and had to be towed back to the city.

Beaudry Leman,10 the General Manager of the Banque Canadienne Nationale, described the Beaudoin counterfeiting effort as “clumsy” and “amateur.”11 However, R. L. Calder, K.C., the Crown prosecutor, said that “the bills were extremely well printed, and almost impossible to distinguish from the legal bills, except that they are said to be perhaps somewhat better finished.”12

Two days later, the five brothers pleaded guilty. Their defence council requested leniency, arguing that the brothers did not realize “the enormity of their crime,” and, as farm labourers, they were “an asset to the countryside.”13 Alfred received a sentence of three years in the penitentiary. Pierre Paul and Maximilien received six months in jail, while the two youngest received suspended sentences and were required to keep the peace for one year.14 Before the judge pronounced sentence, it was revealed to the accused that their mother had passed away the previous day.

As for the remaining two members of the gang, it appears that the Crown dropped the case against Joseph Beaudoin senior. The case against Denis Viger, the alleged engraver, also appeared weak. The last news story on the case reported that habeus corpus proceedings were about to be instituted in an attempt to free him.15

ENDNOTES FOR CHAPTER SIX

1J. W. Murray with V. Speer, Memoirs of a Great Detective: Incidents in the Life of John Wilson Murray (Toronto: Fleming H. Revell, 1905), 160.

2The Globe, “Counterfeiting,” 15 June 1880.

3Likely because of aliases used by family members, the names of the Johnson clan vary widely in newspaper reports. Those used here are based on the most reliable sources.

4Melanson with Stevens, The Secret Service, 9–10.

5New York Times, 6 December 1899.

6The Globe, “Arrest of the Deckers,” 3 February 1900.

7Ibid.

8The Globe, “Anthony Decker Dead,”1 April 1905.

9The Gazette, “Mounties Raid Forgers’ Nest on Lonely Farm,” 2 April 1925.

10In 1933, Beaudry Leman was appointed to the Macmillan Committee, chaired by a famous British jurist, Lord Macmillan. The Committee, set up by the federal government to investigate the merits of establishing a central bank in Canada with a monopoly on the issuance of Canadian bank notes, voted 3–2 in favour of establishing the Bank of Canada. Leman and his fellow Canadian banker, Sir William White, cast the two dissenting votes.

11The Globe, “Flood of Bad Bills Is Menacing Canada,” 3 April 1925.

12The Gazette, “Counterfeit Case Continues Today,” 3 April 1925.

13The Gazette, “5 Plead Guilty to Counterfeit Money Charges,” 6 April 1925.

14The Gazette, “5 Sentenced for Counterfeiting,” 7 April 1925.

15The Gazette, “5 Plead Guilty to Counterfeit Money Charges,” 6 April 1925.