7

BANK OF CANADA NOTES: EARLY SERIES

The Bank of Canada was established in the midst of the Great Depression by R. B. Bennett’s Conservative government in response to widespread criticism of Canadian monetary policy and Canadian banks. The responsibilities of Canada’s new central bank were to “regulate credit and currency in the best interests of the economic life of the nation, to control and protect the external value of the national monetary unit and to mitigate by its influence fluctuations in the general level of production, trade, prices, and employment, so far as may be possible within the scope of monetary action, and generally to promote the economic and financial welfare of the Dominion.”1 In addition to conducting monetary policy and carrying out foreign-exchange and debt-management operations on behalf of the federal government, it also began to issue bank notes—its most visible “product.”

Up until the Bank of Canada opened for business on 11 March 1935, Canadian paper money had been issued by the chartered banks or the Dominion government in a variety of sizes, colours, and designs. Under the 1880 Bank Act, chartered banks were restricted to issuing $5 notes and multiples thereof. The Dominion government issued notes with a value of less than $5 and very large-value notes, such as $100 and $1,000 bills. When the Bank of Canada began operations, the Dominion government discontinued its note issues in favour of those of the new central bank, while the chartered banks were given ten years to phase out their notes.

With a standard series of bank notes in circulation, the general public was better able to spot counterfeit currency. The first Bank of Canada notes, issued in denominations ranging from $1 to $1,000, were unilingual, with matching versions of each denomination released in both English and French.

The new notes were designed and printed by the Canadian Bank Note Company and the British American Bank Note Company to the highest standards of the day and incorporated state-of-the-art anti-counterfeiting devices. Intricately engraved (and difficult-to-copy) portraits of a member of the royal family or a former Canadian prime minister appeared on the face of the notes, with allegorical figures symbolizing agriculture, industry, and commerce on their backs. The coloured notes were made using the intaglio printing process, which left lines of raised ink, detectable to the touch, on the front and back of the notes. Complex, symmetrical patterns of lines, known as “guilloche,” formed the borders. Green dots, or “planchettes,” were also randomly scattered through the high-quality security paper and could be removed by scratching. The usefulness of planchettes as a means of thwarting counterfeiters was initially greeted with some skepticism. S. B. Chamberlain, head of the St. Luke’s Printing Works of London, which was the official printer of Bank of England notes, “questioned the value of ‘those little green spots’ as a security device.”2 Despite this criticism, planchettes were present in all Bank of Canada notes until the Canadian Journey series of notes, the first of which was issued in 2001.

Bank notes, 12 March 1935. Bank of Canada notes hit the streets when the new central bank opened for business in 1935. Despite the word “sample” written across the picture, this photograph may have contravened the Bank’s no-reproduction policy for bank-note images.

(Toronto Daily Star, Bank of Canada Archives, Note Issue Clippings, 1B-251)

$1 (French) 1935 issue, front. Designed by the British American Bank Note Company and the Canadian Bank Note Company Ltd., the first series of notes issued by the Bank of Canada consisted of ten denominations with each note issued in separate French and English versions—the only unilingual series of notes ever produced by the central bank.

(National Currency Collection)

The backs of the new notes featured beautiful images of allegorical figures representing everything from agriculture on this note to fertility and security on others. The highly detailed engravings, aimed at foiling reproduction, contained special microscopic features known to only a select few.

(National Currency Collection)

This detailed image from the back of the note shows the complex engraving and guilloche patterns, as well as the green planchettes that were to be a security feature in Canadian notes for decades to come.

(National Currency Collection)

Anti-Counterfeiting warning (Winnipeg Free Press, 27 February 1935. Bank of Canada Archives, Note Issue Clippings, IB-251)

The new notes also contained what the Canadian Bank Note Company called “secret marks.” These were capital letters inconspicuously integrated into the intricate lathe work that framed the face and back of the notes. Until the proofs identifying these marks were transferred by Canadian Bank Note to the Bank of Canada’s National Currency Collection in late 2011, neither the Bank nor collectors knew that the notes carried these extra security features.

As another deterrent to counterfeiting, Bank of Canada Governor Graham Towers issued a statement warning the Canadian public to be on the lookout for bogus money. He indicated that experience had shown that counterfeiters tried to take advantage of a new note issue.3 There had also been rumours of an alleged U.S. counterfeiting ring about to issue their own “Bank of Canada” notes simultaneously with the official release.4 Before issuing the new notes, the Bank also released a detailed description of them so that the public would have a reasonable idea of what the new money would look like. The Bank’s description did not include pictures of the new notes, however, owing to the legal prohibition against publishing pictures of currency, an injunction that remained in effect into the late 1990s.

Notwithstanding these precautions, counterfeit Bank of Canada notes surfaced within weeks of their release. On 1 May 1935, the Bank of Canada’s Regina Agency spotted bogus $1 and $2 notes among currency that had circulated in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Images of the front and back of genuine notes had been transferred onto tissue paper and pasted onto adhesive paper.5 The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) quickly got their man. Peter Fast, an amateur with no previous convictions for counterfeiting, was captured in mid-May. He was subsequently found guilty and sentenced to two years less one day in the common jail at Prince Albert.6 Harry Elkorich and Steve Tomchuk of Blaine Lake, Saskatchewan, were also subsequently arrested by the Mounties. Both had apparently attempted but failed to copy Bank of Canada notes. Elkorich was imprisoned for one year, while Tomchuk, after eluding the police for several months, received a three-year term for possession of bogus chartered bank notes.

More fake Bank of Canada $1 and $2 notes surfaced at the Bank’s Winnipeg Agency through the summer of 1935. According to experts at the Canadian Bank Note Company, these counterfeits were also made by the transfer process in which ink on original notes was transferred to special paper using a solvent. This created a negative image—the printing would be in reverse. The image was then transferred to blank paper that simulated genuine bank-note paper. The experts concluded that the bogus notes were not dangerous counterfeits since only two or three impressions could be made from an original note before the ink was so faded that the note could not be recirculated.7

Prior to the establishment of the Bank of Canada as the sole issuer of Canadian paper currency, jurisdiction over the investigation and prosecution of counterfeiting cases in Canada was unclear. In 1924, federal authorities, in fact, rejected the idea that they might be responsible, arguing that the administration of criminal laws, including those related to counterfeiting, was under provincial jurisdiction. The RCMP was consequently instructed not to investigate the counterfeiting of chartered bank bills. In a letter to the Imperial Bank of Canada, the federal Deputy Minister of Justice noted that the Department of Finance considered it “inadvisable” for the federal government to assume the responsibility or the cost of detecting or prosecuting cases involving the counterfeiting or the passing of counterfeit bank notes. While the government was prepared to prosecute in cases involving Dominion notes, chartered banks were told to initiate private prosecutions if their notes were counterfeited and passed, and to look to the provincial authorities for police investigations.8

Canadian banks were appalled by this decision. The Canadian Bankers Association succinctly and accurately argued:

Offences against the currency, whether government or bank note issues, might well be distinguished . . . from the case of ordinary crimes. It is true that all crimes are offences against the public, but counterfeiting and uttering are offences against the public in a sense in which the great majority of crimes are not offences. To have only lawful issues of currency afloat is surely of the highest public importance, and in a matter so directly affecting the trade and commerce of the country, the Dominion, it is respectfully urged, might well utilize any of its available machinery to secure the protection of all circulating media. There is power, I need not point out to you, in the legislation under which the Royal Canadian Mounted Police are constituted, for the Government to assign to them the duties here mentioned.9

By 1925, the federal government had grudgingly accepted the banks’ position. In a letter to the Canadian Bankers Association, the RCMP commissioner indicated that it had been decided that the Mounties would henceforth investigate the counterfeiting of bank bills, as well as Dominion notes, and that all banks should notify the federal government, or the nearest RCMP detachment, as soon as a counterfeit bill came to their attention. The commissioner added that any counterfeit refused by a bank should be immediately stamped “counterfeit.” The bank should also retain the note and obtain the name and address of the person who presented it.10

The establishment of the Bank of Canada in 1935, first as a federally incorporated, privately held institution and subsequently, in 1938, as a federally owned Crown corporation, with a monopoly on the production of Canadian bank notes, underscored the need for the RCMP, Canada’s federal law enforcement body, to investigate counterfeiting—an offence that affects all Canadians, regardless of where they live. Even so, as late as 1938, the Department of Finance still argued that “strictly speaking the enforcement of the provisions of the Criminal Code relating to counterfeiting money . . . rests with the Attorney General of the Province concerned.”11 Nonetheless, the department was “anxious” to assist the RCMP in counterfeiting cases. Banks were also encouraged to forward all counterfeit or raised notes that they might receive to the nearest Bank of Canada agency, as agent of the Department of Finance, along with all pertinent information that might help the police. This directive was in accordance with Canada’s Criminal Code, which enjoined persons who came into the possession of counterfeit money to forward such money to the Minister of Finance for disposal.

During the 1930s, the Bank of Canada did not believe that counterfeiting was a significant problem in Canada. In a letter to the Deputy Minister of Finance in December 1938, Donald Gordon, Deputy Governor of the Bank of Canada, wrote that “as far as we know there have been no counterfeits of Canadian notes in recent years,” although he added that there had been a number of “raised” or “altered” notes.12 Gordon was too sanguine. The following year, a number of individuals were convicted in Montreal of counterfeiting and being in the possession of counterfeit notes of the Royal Bank of Canada. Much to the dismay of the Bank of Canada and the Department of Finance, the sentences imposed were very lenient, especially for those convicted of engraving and printing the bogus notes. They received only one-year jail terms.13 Prior to sentencing, the individuals were also freed without bail. In 1940, a major counterfeiting conspiracy was accidentally revealed when a roll of bogus $10 notes spilled from a torn suitcase in the train station of the northern Ontario town of Swastika. (See box: “Wartime Counterfeiting Plot Smashed.”) Roughly $225,000 in counterfeit Canadian and U.S. bills were eventually recovered, along with a printing press and forged plates. Seven individuals based in Noranda, Quebec, were arrested.14

This warning was published in the Financial Post, 15 April 1950, roughly six months after well-made counterfeit $10 bills began to circulate. The bogus notes, made in Buffalo, New York, plagued merchants and law enforcement agencies for several years.

(Financial Post, Bank of Canada Archives, Note Issue Clippings, 1B-251)

The Bank of Canada favoured the introduction of a new note series every five years or so to deter large-scale counterfeiting.15 Counterfeit notes of the old design would be more difficult to pass once notes from that series had been withdrawn from circulation. Forgers would also have to start afresh and try to duplicate plates for the new notes—a laborious and expensive process. In addition, the Bank of Canada could take advantage of changing technology and introduce new security measures into the new series. This desired frequency for new notes did not materialize for various reasons. The second series of Bank of Canada notes was issued earlier than expected, only two years after the Bank opened for business. New bank notes were warranted owing to the death of King George V on 20 January 1936, whose portrait had appeared on the first Bank of Canada bills. Following his death, preparations began for new notes bearing the portrait of his successor, King Edward VIII. These plans were shelved following the new king’s abdication on 11 December 1936. New notes were also needed in response to legislation passed in 1937 that required all notes to be bilingual. Consequently, the first bilingual Bank of Canada notes, introduced in 1937, bore the image of King George VI. Although the Bank began preparations for a new note series in 1940, roughly in line with its desired five-year replacement cycle, plans were put on hold because of the war. A new note series did not appear until 1954 with the accession of Queen Elizabeth II to the throne. It was high time. Dangerous counterfeits—the “Buffalo” $10 bills—surfaced in late 1949 and remained a thorn in the side of the RCMP for several years.

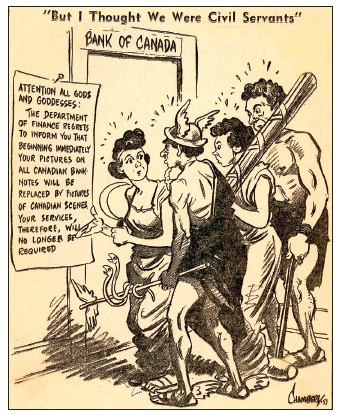

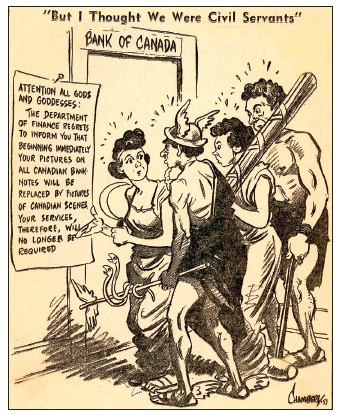

(By permission of the estate of Bob Chambers. 29 October 1953, Halifax Chronicle, Bank of Canada Archives, Note Issue Clippings, IB-251)

The 1954 series of notes, bearing the portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, differed dramatically from their predecessors. Gone were the allegorical figures, traditional design motifs, and ornamentation in favour of distinctly Canadian images with an updated modern look. The new Canadian Landscape series featured Canadian scenes that highlighted the breadth and diversity of the country’s natural beauty. To help foil would-be counterfeiters, the images used in the series became the sole property of the Bank of Canada. All negatives and copies in the possession of the suppliers had to be either destroyed or turned over to the central bank.16 The monarch’s portrait was also moved from the centre of the note to the right-hand side to reduce wear from folding, and the decorative frame was replaced by a soft vignette that the Bank felt would be difficult to reproduce.17 This note series remained in circulation until the late 1960s, although preparations for a new series incorporating the latest security features began in 1963.

$1, 1954 note. Based on a Karsh portrait, the engraving of the Queen appeared on all notes in the Canadian Landscape series. Note the soft shading around the portrait. The green planchettes, or dots, randomly scattered through the bank-note paper were also reformulated to glow under ultraviolet light.

(National Currency Collection)

Counterfeiting is believed to have been insignificant in the mid- to late 1950s, but a serious problem had emerged by 1959.18 In February of that year, a counterfeit $10 bill of the 1954 series was uncovered. It was “printed on good quality paper with an excellent reproduction.”19 It was also extensively circulated, especially in Ontario and Quebec, but also to a limited extent through the western provinces. Although thirty people were arrested in 1960 and charged for possessing and passing these notes, the RCMP was unable to trace the source, which it believed was in Montreal. In the spring of 1960, a new improved version of the same counterfeit $10 bill hit the streets. This note was circulated mainly in Quebec and Ontario. Forty-six individuals, again mostly from Quebec, were arrested and charged.20 Although police believed that they had identified the Montreal-based “syndicate” responsible for printing the bogus bills, and note production ceased, the plates and press were never recovered.

Later that same year, a bogus $100 bill appeared, first in British Columbia and subsequently in Alberta, Quebec, Ontario, and Washington State. Ten people were later charged in Montreal and Toronto, and a large number of bills were seized, although, again, the plates were not discovered. Another batch of fake $100 and $50 bills was seized in July 1960 in a raid on a printing establishment at Larder Lake, in Northern Ontario, close to the Quebec border. Fortunately, none of these notes had made it into circulation. Arrests were made, both in Larder Lake and in Quebec City.21

WARTIME COUNTERFEITING PLOT SMASHED

On the night of 4 February 1940, Thomas McAugherty,22 a conductor on a Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway train running from Noranda, Quebec, to Swastika, Ontario, noted something unusual as people disembarked. Lying under a seat just vacated by a woman was a roll of $10 bills. McAugherty picked up the fallen money and tried to flag down the woman to return it to her. The woman panicked, dropped her heavy trunk-like suitcase, and fled. Such suspicious behaviour prompted the conductor to examine the bills more closely. Thinking that they might be counterfeit, he turned them over to the policeman on duty in the station. After a quick search, Sergeant McDougall of the Ontario Provincial Police found the suspect, Mrs. Nancy Hill of Rouyn, Quebec, hiding under the seat of a nearby bus waiting to depart for Kirkland Lake, Ontario. Unfortunately for Mrs. Hill, her suitcase had ripped, allowing the counterfeit bills to spill out.23 When questioned by police, Mrs. Hill said that she had been given a train ticket and instructions to deliver the suitcase to Toronto. Police later discovered that her case contained engraving plates, inks, brushes, and bogus $10 bills of the Royal Bank of Canada, $50 Bank of Canada notes, and U.S. $20 bills.

Over the next few days, police in Ontario and Quebec, assisted by the U.S. Secret Service, followed a number of leads and rounded up five additional suspects. These included the gang’s ringleader, John Demitrak, who had a prior conviction for forgery; Michael Sawchuck, owner of a Noranda boarding house in which Mrs. Hill, a.k.a. Nancy Sawchuck, cooked; Paul Marton, a photographer from Bourlamaque, Quebec; Matthew Dusiak, a carpenter from Rouyn, Quebec; Peter Stoinoff, a bowling-alley operator in Noranda; and John Wolashyn.24

Police recovered a printing press allegedly used to print the money, five currency plates, and roughly $200,000 in bogus notes. The Globe and Mail reported that the seized plates “were the work of a highly skilled engraver” and that the fake Bank of Canada notes were particularly well made, “expertly coloured” and “almost indistinguishable from genuine notes, except for the paper, which lacked the parchment-like quality” of the real thing.25

During their trial, it emerged that the counterfeiting plot had begun three years earlier in 1937 when Demitrak, Marton, and Wolashyn lived in Kirkland Lake. There, they purchased photoengraving equipment and began to make the plates. Repeated failures and concerns about the consequences should they be caught, prompted the men to abort their project and throw away the plates. Two years later, however, the men relaunched their scheme. Short of cash, they recruited Michael Sawchuck, who provided $110 to buy supplies, including an $85 second-hand printing press. After making satisfactory plates, the conspirators, abetted by Matthew Dusiak, went into production in a shed behind Sawchuck’s boarding house in Noranda. Working eight-hour shifts for several weeks, the gang produced more than $225,000 in fake U.S. and Canadian currency. Wolashyn had second thoughts, withdrew from the plot, and went to work in the gold mines in Northern Ontario. The other conspirators divided the bogus notes among themselves. Nancy Hill, acting as a courier, had been carrying Demitrak’s and Sawchuck’s shares to Toronto when the notes fell out of her suitcase. Demitrak admitted that he had arranged to sell his share of the counterfeit notes to a man in Toronto for $1,000. Apparently, the notes were to be used to buy stolen gold. Sawchuck told police that he had made “tentative arrangements” to sell his share to Hungarian refugees fleeing central Europe. All the bogus money was recovered with the exception of Marton’s share, which he claimed to have destroyed. Only one $10 bill made its way into circulation before it was intercepted by the police.26

THE “BUFFALO” BILLS

Labour Day, 5 September 1949, the Pacific National Exhibition (PNE) was into its last day after an eleven-day run. While the West Coast and Ziegler shows had drawn good crowds, the take at “Happyland” and the concessions of the permanent midway were down over the previous year. The B.C. Electric Railway had closed a streetcar line running to the Powell Street entry to the Exhibition grounds, “killing” business near that gate.27 Added to the concessionaires’ woes was a flood of counterfeit $10 bills. Concession operators had taken in more than $2,300 in bogus bills before the alarm went out and they stopped accepting $10 notes. A further $500 of the bogus notes was found in the receipts of the Exhibition Park racetrack, with another $600 passed in nearby Chinatown. Two men were quickly arrested, but the police feared that Vancouver was awash with bogus currency.28 Simultaneously, the same series of counterfeit $10 notes began surfacing in Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, and Hamilton, as well as other cities throughout southern Ontario.29 As was the case at the PNE, concessionaires at the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto stopped accepting $10 bills.30 An observer at the Bank of Canada noted that this “was the most serious case of counterfeiting that has come to RCMP’s attention.”31

The phony notes were of good quality. According to the deputy secretary of the Bank of Canada, the counterfeit $10 bill was a “photographic reproduction printed on quality paper.” The serial numbers on the notes also corresponded to the serial numbers of genuine notes. He concluded that “it would be difficult for anyone other than an experienced teller to detect this counterfeit.”32 The notes did have flaws, however. The deputy secretary noted that there were no green “planchettes” in the paper and that the portrait of the king and the figure in the “vignette” on the back of the note were fuzzy. The printing was also grey rather than the jet black of the original, and the red ink on the serial numbers smudged when wet.

$10, 1937 issue. The note forged in the “Buffalo Bills” case.

(National Currency Collection)

Subsequent forensic tests revealed that the counterfeits were printed on paper produced by the Holyoke Paper Company of Massachusetts and was of a type not usually exported to Canada. This suggested that the bogus bills, which were produced from photoengraved plates and printed using the offset process, were most likely manufactured in the United States.33

Police arrested many passers of the phony notes across the country. All were small-time criminals who refused to co-operate and divulge their source of supply. Police investigations centred on two gangs in Toronto and one in Guelph that appeared to have access to large quantities of the counterfeit notes. The big break in the case came on 25 September with the arrest of Frank Cipolla, head of the Guelph gang. More than $40,000 in bogus $10 bills was found in his possession.34 Cipolla was arrested after his wife and another woman were stopped by police in Brockville, having passed bogus $10 bills in a number of establishments.35 Although Cipolla refused to provide any information, it was known that certain members of his gang had contacts with gangsters in Buffalo, New York. U.S. Secret Service investigators, working closely with their Canadian counterparts, concentrated their efforts in that city. In April 1950, Salvatore Salli and Anthony Iraci, two of the gang’s kingpins, were arrested in Buffalo. Both Salli and Iraci had lengthy criminal records and had apparently counterfeited ration coupons during the war. The following month, the Secret Service tracked down the plant used to make the Canadian notes, after a power company meter reader reported finding a large quantity of cash stuffed behind a meter in the residence of Matthew Zdolinski of Depew, a suburb of Buffalo.36 In the cellar of Zdolinski’s home, police discovered a Davidson Dual Duplicator—an office machine able to make reproductions using both offset and electrotype plates. The offset plates used to print the notes had been made by Bernard Neuner, a skilled photographer and photoengraver. U.S. investigators subsequently arrested Christopher Mercio and James Wagner. Mercio had acted as liaison between the U.S. and Canadian gangs, while Wagner, who worked at a lithography company in Niagara Falls, New York, supplied technical information and inks.

Police discovered that the gang had purchased the paper used to make the Canadian bills in Cleveland, Ohio, and had produced $500,000 in Canadian counterfeits in August 1949. A similar amount of U.S. currency was also counterfeited. The phony Canadian notes were printed at Zdolinski’s home and then cut at a Buffalo printing company after hours. The finished notes were then brought to Canada for distribution over the Labour Day weekend. Police believed that the bulk of the counterfeit notes were delivered to the Cipolla gang in Guelph.

Forty-eight individuals were arrested in the United States, some receiving prison terms as long as twenty-five years.37 In Canada, a further forty people were charged. Seven were found not guilty, while thirty-three were convicted and given sentences of up to ten years.38

ENDNOTES FOR CHAPTER SEVEN