10

FIGHTING COUNTERFEITING IN CANADA

The unprecedented rise in counterfeiting that Canada saw between 2001 and 2004 was a wakeup call to Canadian authorities. The Bank of Canada responded in its medium-term plan for 2007–09 with a cohesive strategy aimed not only at drastically lowering the number of counterfeits but also at solidly maintaining the level below a threshold of 100 parts per million (this threshold was lowered to fifty ppm for 2010–12). The strategy had four pillars: (1) security—developing notes that are difficult to counterfeit; (2) communications—increasing the routine verification of bank notes by retailers and by the general public through education; (3) distribution—ensuring the quality of notes in circulation by the prompt removal of less-secure older notes; and (4) compliance—encouraging the courts to treat counterfeiting seriously.

Compliance involves the promotion of counterfeit deterrence by law enforcement agencies and the courts. While the Bank itself was responsible for the first three pillars of the new strategy, compliance rested with police officers, Crown prosecutors, and judges. For the strategy to succeed, all elements of law enforcement had to be brought on board. This led to high-level discussions between the Bank, the Department of Justice, and the RCMP.

As Canada’s national police service, the RCMP is unique. Not only does it provide a total federal policing service to all Canadians, it also provides policing services under contract to the three territories, eight provinces (except Ontario and Quebec), more than 190 municipalities, 184 Aboriginal communities, and three international airports. Until 2004, however, the resources that it devoted to fighting counterfeiting were low.

In response to the counterfeiting crisis, the RCMP, supported by the Bank of Canada, developed the National Counterfeit Enforcement Strategy in 2005, which focused on enforcement, prosecution, and prevention. The federal government agreed to provide the program with $3.5 million annually for five years (this funding was renewed in the federal government’s 2012 budget), and a similar amount of the force’s funds were reallocated internally to support the anti-counterfeiting effort. Integrated Counterfeit Enforcement Teams (ICETs) were established in Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver—major centres in the provinces with the highest percentages of counterfeit notes passed and seized. The teams include specialists in counterfeit detection, surveillance, and undercover operations. They are supported by the forensic examiners at the RCMP’s National Anti-Counterfeiting Bureau (NACB), the agency that has the final say on whether a note is a counterfeit. The teams also work closely with specialists from the force’s Technological Crime Branch who assist in examining computers, printers, and other equipment used in counterfeiting operations. The ICETs ensure a national response to organized counterfeiting activity and investigate criminal organizations and individuals involved in the production and mass distribution of counterfeit currency. The strategy also includes regional counterfeit coordinators in Vancouver, Calgary, Toronto, Montreal, and Halifax who work closely with local police forces. Together with regional representatives from the Bank of Canada they also deliver educational programs to retailers, police, and financial institutions.

Educating retailers. Ellen Elliott (left) and Ellen Hall (right) are two of the seven trained Community Policing Volunteers that visited 240 businesses in Squamish, British Columbia, to familiarize them with the security features on the new polymer bank notes. The volunteers are part of the Business Link Program run by the Squamish RCMP.

(Courtesy Squamish RCMP Policing Unit)

THE CRIME

Offences concerning counterfeiting fall under Part XII of Canada’s Criminal Code, Sections 448 to 462. With the exception of Section 457, the following are liable to a maximum sentence of fourteen years.

Section 449: Making counterfeit money

Making or beginning to make counterfeit money

Section 450: Possession of counterfeit currency

Having counterfeit money in personal possession or knowingly

—having it in the possession of another person, or

—having it in any place for the use of himself or another person

Where several people know about the possession, it is deemed to be in the possession of all of them.

Section 452: Uttering counterfeit money

Includes uttering or offering to utter counterfeit money as though it were genuine

Section 457: Likeness of bank notes

Regulates the use of bank-note images for advertisers by specifying colour and size limitations; provides exemptions for RCMP and Bank of Canada employees

Section 458: Possession of instruments for counterfeiting

Making, repairing, buying, selling, or possessing any item used for making counterfeit money

While the RCMP is the lead force in many counterfeiting investigations, the responsibility of enforcement usually falls to the local police force, which may be provincial or municipal. They are also an important source of information on bank notes and bank-note security for the public and provide information and training to cash handlers.

THE EVIDENCE

The NACB is the central repository for all counterfeit money recovered in Canada. Their forensic classification system groups counterfeit notes by their shared characteristics. Counterfeits from the same source are usually readily identifiable; for example, all Wesley Weber notes shared the same identifiable features. They can also be grouped as to production method: ink-jet printer, colour copier, or offset printer. Such evidence is very important in prosecutions.

The prompt submission of notes to the NACB allows timely reports to police who can then establish trends in the occurrences of counterfeiting, as well as common sources. Examiners at the NACB are considered legal experts who can testify in court regarding particular counterfeit bank notes. Their service is available to all police agencies to whom they provide a laboratory report and a Certificate of Examiner of Counterfeits. If a note is found to be genuine, it is returned to the police and then to the source. The NACB is also responsible for destroying all counterfeit notes when they are no longer needed for court.

One of the main objectives of the Bank of Canada’s anti-counterfeiting strategy is ensuring that both police and prosecutors consider the deterrence of counterfeiting to be a high priority. To this end, the Bank has worked closely with police forces to develop educational material for police officers. In collaboration with the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police, the Bank also administers the annual Law Enforcement Award of Excellence for Counterfeit Deterrence, established in 2004 to recognize the front-line work of law enforcement personnel. The Bank organizes monthly and quarterly meetings to review the current counterfeiting situation, where data from the NACB are analyzed, together with information about retailer and public confidence, and any trends and emerging threats in counterfeiting are examined. In addition, the Bank publishes a quarterly newsletter, Anti-Counterfeiting Connections, which provides law enforcement personnel and prosecutors with information on counterfeiting trends and legal proceedings, as well as networking opportunities. The Bank has also worked with police academies and colleges to create a curriculum on bank-note security for students in law enforcement.

Technician at the NACB laboratory examining a note.

(Courtesy RCMP)

The Bank of Canada’s Law Enforcement Award of Excellence for Counterfeit Deterrence. In 2012, the award went to the ICET based in Surrey, British Columbia, for shutting down a major counterfeiting operation in Richmond, British Columbia, before a single note was circulated. This case is documented in chapter 12.

(Courtesy Bank of Canada)

THE PROSECUTION

The prosecution of counterfeiting cases is generally handled by provincial Crown attorneys except in the Yukon Territory, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut.1 Since few trials take place in this specialized field, prosecutors will try to find legal precedents. To provide guidance, the Bank has developed legal resources for the prosecution of counterfeiting offences.

The Prosecutor’s Tool Kit was developed in collaboration with the Public Prosecution Service of Canada and the provincial Attorneys General. It includes trial materials and a database containing sentencing information and sentencing precedents.

The Bank also provides prosecutors with an affidavit that can be signed by the Bank’s regional representative. The statement presents the court with evidence about the prevalence of counterfeiting and its effect on the immediate victim, as well as its potential effect on the community and on society as a whole.

Of twenty-eight convictions for counterfeiting (from 2005 to 2012) analyzed by the Bank, four received conditional sentences, and twenty-four received jail terms. Four of those were less than two years, nine were between two and three years, while eleven were sentenced to more than four years. The longest sentences were for eight years and twelve years.2

Police and prosecutors are treating counterfeiting as the serious crime that it is. In recent years, the RCMP and other police forces have successfully shut down some of the biggest counterfeiting operations ever seen in Canada.

CANADA’S LARGEST COUNTERFEITING OPERATION

The driver of the Brink’s truck was getting worried. It was an autumn afternoon in 2004, and his truck was loaded with cash from businesses all along highway 416 south of Ottawa. He checked with his partner. Wasn’t the grey Hyundai behind them the same car that had been at the last two gas stations? Yes, and at the McDonald’s before that, and Tim Hortons, too. They called police.

Instead of finding the armed robbers they were expecting, police discovered bundles of counterfeit $20 bills. The two men in the car hadn’t even noticed the Brink’s truck as they practised the standard counterfeiters’ ploy—spending phony bills on small items like coffee and receiving genuine notes in change. But the men in the Hyundai were at the bottom of the chain. Organized counterfeiters usually sell large quantities of notes for twenty to thirty cents on the dollar to a distributor who breaks them into smaller bundles and resells them, and so on. The chain ends with the laundering of the notes by small-time crooks like the men in the Hyundai.

It soon became apparent that the forgeries of the Canadian Journey $20s were some of the most sophisticated yet, carrying credible replicas of the holographic strip and watermark.3 The RCMP quickly took over the case. The $20 bill is the “workhorse” of bank notes, accounting for more than 50 per cent of all notes in circulation, and is generally the note distributed by automatic teller machines. A loss of confidence in this bill could have had serious negative repercussions for the financial system.

The investigation, dubbed Project Ophir, lasted ten months and involved extensive surveillance and an undercover police officer who purchased more than $125,000 in counterfeit currency from the highly organized and sophisticated group of criminals. After executing twelve search warrants on businesses, residences, and vehicles, police raided a site in North Toronto and recovered a total of 383,634 bank notes with a face value of more than $6.7 million. “‘It was the largest counterfeit manufacturing plant in Canadian history,’ said Cpl. Tim Laurence, the RCMP’s lead investigator on the case.”4 Rehan Bawania and Taimaz Ejtehad were arrested in June 2006, together with others, and both pleaded guilty to an array of offences related to the production, distribution, and possession of counterfeit currency. They were released on bail to await sentencing.

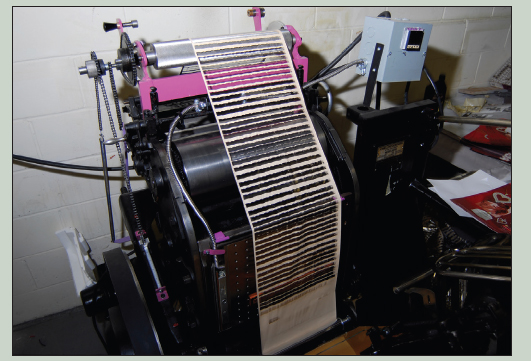

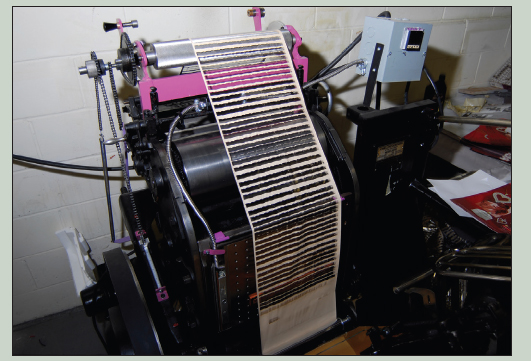

Equipment for producing phony holographic stripes, seized in Project Ophir.

(Courtesy RCMP)

Piles of notes seized in Project Ophir II being measured and prepared as evidence.

(Courtesy RCMP)

It wasn’t long before more counterfeit $20 notes began surfacing in the Toronto area—notes suspiciously similar to those from Project Ophir. Another investigation began—Ophir II—and in May 2009, police seized $4.2 million in counterfeit $20 notes at a site in Markham, and once again arrested Bawania and Ejtehad, the kingpins of the operation.

In January 2010, both men again pleaded guilty to numerous charges, and this time they were quickly sentenced. Bawania received twelve years and Ejtehad eight years. The judge took note of the Bank of Canada’s victim impact statement and in his decision noted that “money in a democratic capitalist society such as Canada, is the medium of exchange both personally and in our commercial world. The production and distribution of the quantities of money involved in this case infect and compromise the ability of decent, honest, hard-working people to conduct business by destroying the fabric and value of the money they work so hard to obtain.”5

THE RESULTS

Counterfeiting in Canada had been reduced to twenty-eight parts per million in 2012 with a value of roughly $1.6 million—the lowest level in years—compared with 470 parts per million, with a value of $13 million, as recently as 2004. Moreover, virtually all of the counterfeits passed in 2012 were of older series. Less than a handful were counterfeits of the most recent and most secure polymer notes, and all were poor reproductions. But danger lies in that success. It is important to maintain a focus on counterfeiting in the face of the other priorities that face police and prosecutors. Strong enforcement removes counterfeit notes from circulation and, in many cases, prevents them from ever being distributed. That level of enforcement maintains the public’s confidence, confidence that once lost is hard to regain. Indeed, despite the recent success in reducing the level of counterfeiting, confidence in notes has improved only modestly.

While the volume of counterfeiting is expected to continue to decline with the introduction of the new highly secure polymer series, counterfeiting can emerge at any time, and as the episode in 2004 revealed, it can explode with little warning. In fact, within weeks of the new $100 polymer note being issued, a counterfeit “polymer” $50 appeared, long before the bank released the new $50 note. Although it was a crude, almost laughable attempt at duplication, it sent a message.6 No matter how confident you feel about the security of your bank notes, you can never let your guard down.

A collection of really bad counterfeits that were successfully passed before being turned over to the RCMP. In this group, one note has foil taped to it, one of the twenties has “specimen” across the front, and the $10 is coloured with crayon! It really pays to check!

(Courtesy RCMP)

This really bad counterfeit appeared before the new $50 polymer note had even been released. The image on the front had been taken from the Bank of Canada’s website and still had “specimen” printed across it, while the back carried the image of the RCMP musical ride from the Bank’s 1975 Scenes of Canada $50 note. And, oh yes, the note was printed on paper.

(Courtesy RCMP)

BOGUS COINS

Most modern circulating coins are made of base metals, which gives fraudsters little incentive to counterfeit them, unlike the days when coins were made of gold and silver. Moreover, the relative potential payoff from counterfeiting large-value bank notes is much higher. Nonetheless, counterfeit coins turn up from time to time. In the United Kingdom in 2010, the Royal Mint reported that 2.94 per cent of £1 coins were counterfeit and that there had been a gradual increase in the number of counterfeits in circulation since 2002.7 The Royal Mint noted that the counterfeit coins were not always easy for the layperson to spot and that roughly half of the fake coins had fooled vending machines.8

Although the Royal Canadian Mint does not supply estimates of counterfeit coins in circulation, the amount of coin counterfeiting in Canada is believed to be very low. Nonetheless, in 2006, RCMP and Quebec police broke up “a highly sophisticated counterfeit ring” making $1 and $2 coins in Repentigny, northeast of Montreal. Equipment, material, and bogus coins ready for circulation were discovered.9 In 2010, the RCMP reported that in the previous four years only 4,230 fake $2 coins had been discovered.

In 2011, owing to rising metal prices, the Mint announced that it would switch from nickel to steel in the production of $1 and $2 coins. While the Mint did not believe that the security of existing coins had been compromised, new security features were added to the new steel-core coins, “including a lasermark, virtual images, and edge lettering” to thwart potential counterfeiters.10

REPRODUCTION OF BANK-NOTE IMAGES

Given understandable concerns about counterfeiting, almost every country has restrictions on the reproduction of bank-note images, even when the aim is not to defraud the public. In some countries, the duplication of notes, in whole or in part, even for artistic or advertising purposes is strictly prohibited. Such restrictions prevent the circulation of simulated notes as genuine and support the enforcement of the Criminal Code.11

Until quite recently, Canada’s policy was very restrictive. Simulations of bank notes were allowed only if one colour was used; there was no representation of a human face or figure, other than in a very general way; no photography was used except in the transfer of the finished drawing to a printed surface; and, other than the word CANADA, no word, letter, or numeral was duplicated. As well, nothing in the likeness of the back of a note could be published or printed in any form. The law applied to all “current” notes, which were defined as all notes issued by the Bank of Canada since its establishment in 1935, as well as notes issued by Canadian chartered banks.

In its May 1972 edition, Maclean’s magazine used the image of a $10 note to illustrate an article on Canada’s currency. The police launched an inquiry and found the magazine to have contravened the law on duplication of bank-note images. Maclean’s was subsequently made to destroy the plates used to reproduce the bill.

(Bank of Canada Archives, reprinted with permission of Torstar Syndication Services)

However well-intentioned, this policy gave rise to ludicrous situations. Brochures aimed at educating the general public about new bank-note issues and their security devices, even those prepared by the Bank of Canada, could not contain illustrations of bank notes. Catalogues for collectors were prohibited from printing pictures of historic notes. Questions were even raised about the legality of televised images of bank notes. However, even if the RCMP was prepared to press charges, provincial attorneys general were rarely willing to prosecute in cases of “innocent” duplication, since there was no criminal intent. Users of bank-note images, often financial institutions advertising financial products, typically received a warning and were told to stop and turn over any plates to the police.

Through the 1980s, efforts to update the legislation were a source of considerable friction between the Bank of Canada and the RCMP. While the Bank sought liberalization of the law, the police preferred the status quo. The RCMP argued that “it would be highly desirable if the reproduction of Canadian and foreign currency could be prevented because every such action tends to encourage others to do the same and such practices cheapen the position of bank notes in the public eye. In addition, and more importantly, the plates could fall into other hands to be used for a wrongful purpose.”12

The situation came to a head in late 1989 when the Globe and Mail published a photograph of a finger holding up a new $50 bill that the Bank of Canada had just released.13 Shortly afterwards, the RCMP contacted the Bank of Canada asking whether the Bank would be embarrassed if charges were laid against the newspaper. The answer was a definite yes. The digit appearing in the newspaper picture with the $50 bill belonged to a Bank of Canada official.14

Commenting on the situation, the Bank’s scientific adviser wrote, “A common-sense view . . . is that . . . no possible harm has occurred to any person, institution, or the Canadian public by the action of the Globe and Mail.” He added that “Canada is one of the very few countries which have such draconian legislation” and that “the law which proclaims the action as criminal should be abolished, or at least amended.”15

Amendments to the legislation finally became law in 1999. Under Section 457 of Canada’s Criminal Code, simulations of bank notes are now permitted if they are significantly smaller or larger than genuine notes and are printed in black and white, or only on one side. To avoid the risk of contravening the law, the Bank of Canada insists that people who wish to reproduce a note seek its permission. Its decision is based on whether the reproduced image could be mistaken for a genuine note, and whether the proposed use might tarnish the dignity and importance of currency to Canadians. Bank permission is not required to use bank-note images in videos or films that depict currency in a general way. For more information on the legal reproduction of bank-note images, see the Bank of Canada’s website, or the website of the Central Bank Counterfeit Deterrence Group (CBCDG).16

ENDNOTES FOR CHAPTER TEN