1

From admiration to defence

‘That is what you are doing with your scenery!’ With his paintbrush held aloft, John Ruskin, the writer, art historian and philosopher, shocked his audience by defacing a painting by his hero and national celebrity J. M. W. Turner. It was a landscape of Leicester Abbey, and across its glass frame he scrawled a monstrous iron bridge, a heavily polluted river and billowing smoke.

The only surviving account of this event, a lecture Ruskin gave at Oxford University, comes from a student who was present, the young A. E. Housman, who would go on to write one of the best-loved elegies to England, A Shropshire Lad. But for the moment, he and his fellow students were awed by the Slade Professor of Fine Art’s blatant confrontation of modern civilisation. ‘The atmosphere is supplied – thus!’ Ruskin continued, dashing a flame of scarlet across the picture, which became first bricks and then a chimney from which rushed a puff and cloud of smoke all over Turner’s sky. Housman describes how Ruskin threw down his brush amidst a tempest of applause, his students enthralled by the idea that beauty could matter as much, if not more, than the unconstrained pursuit of wealth.

Those were radical ideas in the 1870s, but support was building for Ruskin’s views. For as well as bringing great wealth and innovation, industrialisation was casting a pall over a nation whose countryside was internationally admired; whose poets, artists and writers were renowned for celebrating it; and whose identity was shaped by its beauty. The fight for beauty had begun, and Ruskin was at the heart of it.

The beauty of Britain’s nature and landscape has long captivated the people of this country and has taken many forms. Chaucer wrote lyrically of the countryside’s awakening in the spring as part of the inspiration for ‘folk to goon pilgrimages’; and mediaeval craftsmen painted and sculpted exquisite flowers, leaves and creatures into the friezes, pillars and gargoyles of cathedrals and country churches. As well as vivid descriptions of nature and landscape in his sonnets and plays, Shakespeare’s evocative settings – whether the leafy Warwickshire Forest of Arden or the bleakness of Macbeth’s Scottish hills – are central to the appreciation of his texts. Thomas Traherne, a century later (he was born in 1636), captures the religious underpinning of much appreciation of landscape and nature in Centuries of Meditation: ‘This visible World is wonderfully to be delighted in, and highly to be esteemed, because it is the theatre of God’s righteous kingdom.’

Beauty was a word freely used and invoked, whether by young men in search of Arcadia as they travelled the continent on the Grand Tour, educating and preparing themselves for their future lives, or by the many people inspired by the increasingly popular school of landscape painting, led by Thomas Gainsborough in England and Richard Wilson and Thomas Jones in Wales. Thomas Gray’s romantic 1719 ‘Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard’, celebrating the beauty of nature and everyday country life, reached unprecedented heights of popularity, becoming one of the most quoted poems of the English language.

The early eighteenth century was a time of burgeoning interest in aesthetics, and Edmund Burke, in his 1757 Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, drew a distinction between what was considered beautiful, derived from love or pleasure; and what was sublime, triggered by pain or terror. Burke presented the sublime and the beautiful as antithetical, with the sublime inspiring delight at terror perceived but avoided, emotions echoed in Daniel Defoe’s descriptions of Westmoreland [sic] in his Tour through the Whole Island of Great Britain as ‘a country eminent only for being the wildest, most barren and frightful of any that I have passed over in England, or even in Wales itself’. Beauty, on the other hand, was triggered by the warmer emotions of love and sensuality, and it was clear that the human-created world could be made to replicate, in a milder form, and closer to home, the affirming power of nature.

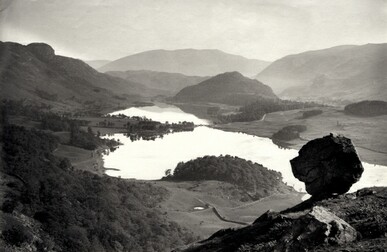

An engraving of the dramatic scenery that inspired thoughts of the sublime: Thomas Smith of Derby’s view of Ennerdale (© UK Government Art Collection).

The gentleman’s park, for instance, was a conscious attempt to enhance the natural landscape, sweeping away earlier manor houses and the structured form of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century gardens and replacing them with classical houses and ‘landscapes’ decorated with temples and monuments: expertly designed but natural-looking prospects which reconstructed the elements of ancient Arcadia in the countryside of Britain.

The person most in demand to create such idylls was ‘Capability’ Brown, the ‘omnipotent magician’ as William Cowper dubbed him after his death. Born in Northumberland, Brown trained under William Kent at Stowe, in Buckinghamshire, and went on to design or contribute to at least eighty landscape gardens in England. His wide, sweeping lawns with their perfectly placed serpentine lakes, and their neo-classical buildings carefully positioned to create an idealised view, represented the pinnacle of many eighteenth-century landowners’ aspirations. But he would have rebelled against the idea that his creations were entirely artificial. He was inspired by Alexander Pope’s instruction that landscape design should draw on the underlying ‘genius of the place’, a concept which shapes much thinking about landscape to this day:

Consult the Genius of the Place in all;

That tells the Waters or to rise, or fall;

Or helps th’ ambitious Hill the heav’ns to scale,

Or scoops in circling theatres the Vale;

Calls in the Country, catches op’ning glades,

Joins willing woods, and varies shades from shades;

Now breaks or now directs, th’ intending Lines;

Paints as you plant, and, as you work, designs.

(Alexander Pope, ‘Epistle IV’, addressed

to Lord Burlington, Moral Essays, 1731)

By the end of the eighteenth century tastes were changing and new ideas about beauty were emerging, favouring the countryside’s own qualities rather than those which were imposed upon it. William Gilpin, priest, artist and schoolmaster, proposed the ‘picturesque’ as something of a third way between the sublime and the beautiful, reflecting the naturalistic character of the British countryside, created without apparently conscious intervention: ‘Picturesque beauty is a phrase but little understood. We precisely mean by it that kind of beauty which would look well in a picture. Neither grounds laid out by art nor improved by agriculture are of this kind.’

In the 1760s Gilpin published accounts of his visits to the Lake District and the Wye Valley, prompting thousands of eager tourists who were drawn by his descriptions to explore the picturesque beauty of England’s countryside. Of the ancient trees of the New Forest he wrote: ‘Such Dryads! Extending their taper arms to each other, sometimes in elegant mazes along the plain; sometimes in single figures; and sometimes combined.’ Many followed his lead, clutching their sketchbooks and Claude glasses to frame the perfect view. His cause was taken up by Uvedale Price, a Herefordshire squire, who praised the ‘real’ countryside as a work of art, and also Humphry Repton, with whom he travelled down the Wye, because he (Repton) ‘really admired the banks in their natural state, and did not desire to turf them, or remove the large stones’. And as the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars restricted continental travel, enthusiasm for the landscapes of Britain was re-energised.

By the end of the eighteenth century the whole population could be said to be falling in love with nature and the British landscape. In addition to the tourists following Gilpin’s scenic routes, Gilbert White’s Natural History of Selborne and Thomas Bewick’s History of British Birds inspired a new generation of nature lovers. White’s finely observed, unsentimental prose described, named and publicised many species for the first time; and Bewick’s beautiful engravings formed a popular and widely used reference book, encouraging the fashion for bird identification. As the eighteenth century gave way to the nineteenth, the Romantic poets inspired a new generation of landscape and nature lovers, their outpourings devoured by a nation hungry to appreciate their pastoral, beautiful imagery of England.

And this was no superficial appreciation: William Wordsworth’s ‘Lines Written a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey’ (1798) enjoin us not only to appreciate nature but to accept its moral depths:

to recognise

In nature and the language of the sense,

The anchor of my purest thoughts, the nurse,

The guide, the guardian of my heart, and soul

Of all my moral being.

Wordsworth also brought something new. He had been born in Cockermouth in the Lake District in 1770 and grew up with a deep love of nature, travelling widely in France, Switzerland and Germany before settling again in his childhood home. By the time he published, in 1810, his best-selling Guide through the District of the Lakes he was tapping into a population hungry for the appreciation of its own countryside. He gave people routes and viewpoints, places to stay and sights to see. And his statement that the Lake District was ‘a sort of national property in which every man has a right and interest who has an eye to perceive and a heart to enjoy’ hinted at a universal stake in its landscape. Because while his predecessors as writers and poets had helped the nation to love nature, Wordsworth’s readers got something more. This revered place, his beloved Lake District, was coming under threat, and the stage was set for the first great clash about beauty. Admiration was about to tip into defence, and Wordsworth’s was the voice that brought this about.

William Wordsworth, whose passion for the Lake District tipped admiration of its beauty into defence.

During the early nineteenth century a new breed of business opportunists spotted the commercial potential of the age-old industries of the Lake District: slate quarrying, and mining for copper and other valuable minerals. They also wanted stylish places to live in the Lake District’s beautiful valleys. Wordsworth, whose passion for long, solitary walks meant that he knew the Lakes intimately, was among the first to raise the alarm, speaking out in his Guide against the construction of ugly villas in its beautiful valleys. In 1844 he fired off eloquent letters to The Morning Post objecting to a railway line that might link Kendal to Windermere and spoil for ever the solitude of a wilderness ‘rich with liberty’. In the same year he wrote the sonnet with which his passion for the Lake District has been ever since associated:

Is then no nook of English ground secure

From rash assault? Schemes of retirement sown

In youth, and ’mid the busy world kept pure

As when their earliest flowers of hope were blown,

Must perish; – how can they this blight endure?

And must he too the ruthless change bemoan

Who scorns a false utilitarian lure

’Mid his paternal fields at random thrown?

Baffle the threat, bright Scene, from Orrest-head

Given to the pausing traveller’s rapturous glance:

Plead for thy peace, thou beautiful romance

Of nature; and, if human hearts be dead,

Speak, passing winds; ye torrents, with your strong

And constant voice, protest against the wrong.

(Wordsworth, ‘On the Projected

Kendal to Windermere Railway’, 1844)

Wordsworth had already railed against the ‘spiky larch’, a new tree brought in to launch commercial timber growth in the Lakes, and for the rest of his life he fulminated against the despoliation of the landscape he loved.

As the fight in the Lakes began, the ‘rash assault’ was gathering pace across Britain’s industrialising landscape. Mechanisation and the growth of manufacturing during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries brought great wealth to those able to reap the profits of trade and manufacturing. But their social and aesthetic consequences were often dire, especially in the rapidly growing cities and towns. Mills and factories colonised riversides and green fields, and filthy smoke and pollution choked their surroundings. Houses thrown up for mill and factory workers were often poor, mean and overcrowded.

To some the vision was apocalyptic. In 1798 the Reverend Robert Malthus published his Essay on the Principle of Population arguing that population growth would outstrip food supplies and the world would end in chaos and misery. His reasoning was based on simple mathematics: because population multiplies geometrically and food production arithmetically the population would inevitably collapse when food supplies failed, ‘The power of population is indefinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man.’ He was one of the first to recognise that there were limits to the Earth’s capacity to cope with human demands.

His essay, though, provoked a storm of protest. Marx and Engels argued that the crisis was due not to ‘natural’ causes but to capitalism denying resources to the poor; while the capitalists argued that Malthus had failed to recognise that increases in productivity would feed the poor. His critics were proved right and Malthus wrong. Extreme poverty was due at least as much to unequal access to food as to its availability (the same is true today), and food production expanded dramatically during the nineteenth century due to technological innovations.

What no one could fail to observe, though, were the ‘processes of misery and vice’ experienced by those whose basic needs were not met. Within the teeming cities filthy, polluted air wreaked havoc with people’s health, and children employed in the factories and mills suffered appalling injuries and were deprived of sunlight, play and freedom. Medical facilities were virtually non-existent, or too expensive, and babies were routinely doped with opiates so their mothers could work. Average life expectancy fell as many died young, their lives broken by working in the mines, mills or factories, and child mortality rose through a combination of poverty, sickness and accidents.

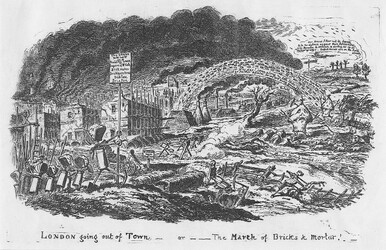

Apocalyptic, too, was the physical footprint of urbanisation. George Cruikshank’s 1829 cartoon London Going Out of Town, or The March of Bricks and Mortar captures the disastrous consequences as newly built but already-decaying tenements stand gloomy and forlorn; a kiln fires a barrage of hot bricks over a cornfield, whose haystacks, terrified, call out ‘Confound these hot bricks! They’ll fire all my hay ricks’. A tree is cast to the ground crying ‘Oh! I’m mortarly [sic] wounded’ and a robotic army advances from the city into the countryside, while trees sway wildly and cattle and sheep flee from fields which have already become building sites.

George Cruikshank’s 1829 cartoon captured the horror of unplanned urbanisation. (Courtesy of the Museum of London)

Britain was a land of inconsistencies and contrasts. Enormous wealth sat alongside desperate poverty; objects and architecture of great beauty contrasted with the pitiful squalor of poor people’s homes and the implements of drudgery; and the glorious, verdant forests and landscapes with the filth of rapidly growing, overcrowded cities.

Out of this cacophony came a powerful voice for beauty. John Ruskin was born in 1819 and observed at first hand this world of rapid change and social division. Though variously a scientist, philosopher and educator, he was always obsessed by beauty. As a precocious child he had measured the blue of the sky with a cyanometer, and his early written works, especially Modern Painters, were underpinned by references to his own love of beauty as well as celebrating artists such as Turner who best represented the brilliance of nature’s stormy skies and swirling seas. His early sensibility to art and architecture (he wrote his first book, Poetry and Architecture, as a teenager) matured into a passionate love for the countryside and an intense hatred of the obsession with money, machinery and mechanisation that threatened to drive all that was beautiful out of the world. And his awakening to the deeper meaning of beauty at Chamonix shaped his whole life, framed by a profound commitment to social justice as well as aesthetics. Not for him was beauty defined by the elite; it was close to home and belonged, as of right, to everyone.

Drawing on deep though constantly challenged religious and ethical beliefs, Ruskin became a social reformer and campaigned for beauty, justice and moral virtue. He saw no division between the three. ‘Beauty,’ he wrote in Volume II of Modern Painters (1846) ‘is either the record of conscience, written in things external, or it is the symbolizing of Divine attributes in matter, or it is the felicity of living things, or the perfect fulfilment of their duties and functions. In all cases it is something Divine.’

But only a decade later his mood had switched to despair:

Once I could speak joyfully about beautiful things, thinking to be understood; – now I cannot any more; for it seems to me that no-one regards them. Wherever I look or travel in England or abroad, I see that men, wherever they can reach, destroy all beauty. They seem to have no other desire or hope but to have large houses and to be able to move fast. Every perfect and lovely spot which they can touch, they defile.

(Modern Painters, Volume V, 1856)

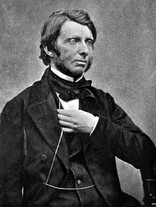

John Ruskin’s was the powerful voice who raised expectations and demands for beauty in the nineteenth century. (Courtesy of the Wellcome Library)

Ruskin took up the mantle of Wordsworth’s defence of the Lake District after the poet’s death in 1850, scorning in particular the railways that were defiling the places he loved. He condemned plans (never fulfilled) to build railways to connect the Honister slate quarries in the Newlands Valley with the railway line at Braithwaite, running tracks through Borrowdale along the pristine western shoreline of Derwentwater; and to link Keswick and Windermere by rail:

The stupid herds of modern tourists let themselves be emptied, like coals from a sack, at Windermere and Keswick. Having got there, what the new railway has to do is shovel those who have come to Keswick to Windermere, and to shovel those who have come to Windermere to Keswick. And what then?

His riposte to the Midland line through Monsal Dale in the Peak District which was built in 1863 was similar: ‘now, every fool in Buxton can be in Bakewell in half an hour and every fool in Bakewell in Buxton.’

Ruskin was sickened by the destruction of beauty in the countryside, but he also deplored the unplanned, inhumane growth of cities. In The Seven Lamps of Architecture he described how it was ‘not possible to have any right morality, happiness, or art, in any country where the cities are . . . clotted and coagulated’; arguing that instead ‘you must have lovely cities . . . limited in size, and not casting out the scum and scurf of them into an encircling eruption of shame, but girded each with its sacred pomoerium, and with garlands of gardens full of blossoming trees and softly-guided streams.’

To put his ideas into practice, Ruskin set up the Guild of St George, for which he wrote a monthly bulletin, Fors Clavigera. Its aim was to acquire land and beautiful objects so that its members could live according to its (surprisingly authoritarian) principles.

We will try to take some small piece of English ground: [he wrote in 1871] beautiful, peaceful and fruitful. We will have no steam-engines upon it, and no railroads; we will have no untended or unthought-of creatures on it; none wretched, but the sick; none idle, but the dead. We will have no liberty upon it; but instant obedience to known law, and appointed persons; no equality upon it, but recognition of every betterness that we can find, and reprobation of every worseness.

Ruskin envisaged a world where social justice, human effort and a deep appreciation of nature and the intrinsic beauty of art and architecture would unite to create a society in harmony with itself. Members of the Guild would live wholesome and rewarding lives dependent on the forces of nature – water, human and horse-power, not machines – in communities committed to education, fairness and collective decision-making.

Ruskin’s utopian vision struggled to gain a footing, however. Although he invested a tenth of his own fortune in the Guild he failed to attract much support. By 1884 the Guild numbered only fifty-six members and its assets were small: a few cottages in Barmouth left by Fanny Talbot (who later also donated to the National Trust its first property, Dinas Oleu); a few small farms including two, plus forest land, in the Wyre Forest near Bewdley; a mill on the Isle of Man; and the St George’s Museum in Sheffield, furnished with objects acquired by Ruskin. Disappointment that the Guild did not thrive in his lifetime (though it continues today, doing much good work) was a source of sadness to Ruskin and contributed to his failing health and declining mental state.

All the same, Ruskin’s public persona was extraordinarily influential. He was a prolific writer and correspondent and an impassioned and charismatic public speaker. His lectures in the great cities of Britain were attended by thousands, and his eloquence inspired many followers. There are frequent references to Ruskin in Hansard, his lectures inspiring not just students but those occupying the highest offices of public life as he called for beauty to be taken seriously.

And he left a powerful legacy. Not least was the way his ideas found practical expression in a new architecture. He personally sponsored Oxford’s new Museum of Natural History, drawing on the principles of perfection he had articulated in The Seven Lamps of Architecture and The Stones of Venice, written in veneration of mediaeval Venice as it crumbled in the first half of the nineteenth century. Many cities commissioned magnificent buildings – though he hated some of them – as homages to his championship of the Gothic: Manchester Town Hall, Bradford City Hall, St Pancras Station and the Albert Memorial in Kensington Gardens.

Perhaps more important, though, were the people he inspired: people who would carry forward his ideas as his own health declined, ensuring that his passion for beauty remained alive as Britain shuddered into a new century. And linked to these people were organisations whose foundation and purposes drew heavily on his ideas.

Among his most prominent followers were William Morris, inspirer of the Arts and Crafts movement which has left its own legacy in beauty; and the three founders of the National Trust: Octavia Hill, Robert Hunter and Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley.

Morris was at the heart of the pre-Raphaelite movement of painters and designers. As an Oxford undergraduate he was inspired by mediaeval history and buildings as well as Ruskin’s writing. He trained as an architect and in 1861, with his close friends the artists Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and the architect Philip Webb, he founded the decorative arts firm that would become Morris and Co. The company shaped the fashion for interior decoration throughout the Victorian period and beyond, creating tapestries, wallpaper, fabrics, furniture and stained-glass windows. ‘Beauty,’ Morris wrote, ‘which is what is meant by art . . . is no mere accident to human life, which people can take or leave as they choose, but a positive necessity of life.’ And he memorably enjoined his clients to ‘have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.’

In 1877 he established the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) to promote sensitive principles of repair and preservation, seeking ‘truth not pastiche’. SPAB was directly inspired by Ruskin’s The Seven Lamps of Architecture, which attacked restoration and urged new skills of trusteeship and sensitive conservation. It was known as ‘Anti-Scrape’, rejecting earlier, brutish tendencies to restore by destroying the patina of age and evolution. By the 1880s, as Ruskin’s health was declining, Morris became a revolutionary activist, socialist and radical writer. His epic News from Nowhere described his utopian vision, no less ambitious than Ruskin’s, set in a future London. It depicted an epoch after a socialist revolution; a land of beauty and art. Like Ruskin, Morris was profoundly anti-urban; rejecting the evils of nineteenth-century cities as symbolic of greed, misery and destructive competitiveness. At the first meeting of the London Committee of the Kyrle Society he addressed the members by saying ‘he could not be otherwise than discontented, while the aspect of London was so squalid’.

The Kyrle Society for the Diffusion of Beauty was named after the English philanthropist Robert Kyrle, whose work to improve and embellish the town of Ross-on-Wye was widely admired, and was set up in 1876 by Miranda Hill, Octavia’s sister. Its purpose was, straightforwardly, ‘to bring the refining and cheering influences of natural and artistic beauty to the people’. Drawing heavily on Ruskin’s ideas its members provided art in public places, decorated hospitals and schools, organised choirs and laid out gardens. Its four committees – decorative, musical, literature distribution and open spaces – were all energetic, but its open spaces branch left the greatest legacy, securing the clearing and opening of sixty-two London burial grounds (which had hitherto been kept locked and closed because they were so filthy and dangerous) as gardens for the poor. Arguably its finest hour came when it raised nearly £10,000 from a public appeal to establish and open Vauxhall Park in 1890, though it reluctantly handed the park over to the Lambeth Vestry as the Kyrle Society was not constituted to own and manage land. The Society stimulated the formation of many branches to champion beauty in towns and cities across the country, often joining with local antiquarian and historical societies to press for the protection of important local buildings, green spaces or vernacular architecture during the endless process of urban building and remodelling. Many of today’s civic societies began life as local branches of the Kyrle Society.

At a national level, though, its ideas were embraced and ultimately subsumed by the National Trust, an organisation whose birth and purposes are deeply Ruskinian. Its three founders were each, in their own way, indebted to him, and their personal commitment to beauty established deep roots within the Trust.

The first was Octavia Hill, who met Ruskin when she was a teenager. Born in Wisbech in 1838, she seemed destined for a philanthropic life. Her maternal grandfather, Thomas Southwood Smith, was the first doctor to demonstrate the link between infectious diseases like typhoid and poor living conditions. Her father, James Hill, was a committed follower of Robert Owen’s philanthropic ideas but he became bankrupt and largely disappeared from Octavia’s life when she was a child. Caroline, her mother, was her role model and mentor, and she encouraged the fourteen-year-old Octavia to supervise a classroom of girls making toys within the Ladies’ Guild she had established in the Working Men’s College in Russell Place.

When John Ruskin, as a friend of the Christian Socialist preacher F. D. Maurice, visited the Guild in 1853 Hill was captivated by him. She was already a disciple of Maurice’s, passionately supporting his belief in people’s entitlement to decent living conditions and educational opportunities. She was more than ready to follow Ruskin, and when he invited her to visit him at his house in Denmark Hill and become one of his copyists she accepted, slaving to produce accurate copies of the Italian Masters. For years she tried to combine this work, for which she was not temperamentally suited, with her own philanthropic efforts. She and Ruskin became close but he knew she was destined for other things and early in their relationship he wryly remarked, ‘If you devote yourself to human expression, I know how it will be, you will watch it more and more, and there will be an end to art for you. You will say “Hang drawing!! I must go and help people.” ’ Hill denied it but he was right. Less happily, in the 1870s, they fell out after he accused her of questioning his ability to conduct any practical enterprise successfully. Again she denied the charge but it was hardly untrue. It created a rift between them that was never fully to heal.

At the heart of Hill’s beliefs was the importance of bringing beauty to people, and as a teenager she used to lead groups of ragged schoolchildren out of London on a Sunday, sometimes as far as Romford or Epping Forest and back, to let them experience clean air, growing grass, trees and flowers. This remained a guiding motive throughout her life: ‘The need of quiet, the need of air, the sight of sky and of things growing seem human needs, common to all.’

The young Octavia Hill brought beauty and dignity into people’s lives by buying up housing in poor condition and providing decent homes for families to live in (courtesy of the National Trust) – pictured above is her first project, Paradise Place, as it is today.

But she also saw with piercing clarity that what people most lacked was clean, wholesome conditions at home. With Ruskin’s financial backing, at the age of thirty-two she bought three squalid cottages in the inappropriately named Paradise Place in the heart of Marylebone and set them up as tenancies. She was an unusual and interventionist landlord, marked for her humanity and practicality. She improved the houses before her tenants moved in and insisted they maintain them as decent and clean places to live. Against the conventions of the day she collected the rent herself and, by knowing her tenants personally, was often able to help resolve their problems and find them work. She was intolerant of those who did not live by her high moral standards, but she was a world away from the Dickensian landlords of the time, believing in dignity and self-reliance. Her passion was to relieve ugliness as well as poverty:

let us hope that when we have secured our drainage, our cubic space of air, our water on every floor, we may have time to live in our homes, to think how to make them pretty, each in our own way . . . because all human work and life were surely meant to be like all Divine creations, lovely as well as good.

She made sure her housing schemes were near to places where people could walk and find beauty. The Red Cross Cottages she built in Southwark, today still occupied, scrunched below The Shard, all have their own patch of garden as well as a communal open space that brings brightness and pleasure to a densely packed inner London borough. She would insist on a window-box or a tiny courtyard for the children to play in if that was all that was possible.

Though fundamentally philanthropic, Hill ran her housing schemes (by 1874 she had over three thousand tenancies in fifteen sites in London) as a business, returning to Ruskin and her other investors a reliable five per cent a year. As her business expanded it became more sophisticated, but she never deviated from the principle of employing women rent-collectors whose personal touch was crucial to her tenants’ ability to thrive. She was extraordinarily assiduous: working long hours, maintaining relationships with hundreds of volunteers and supporters, fundraising endlessly, and writing every year to account for her activities in her Letters to Fellow Workers.

Octavia Hill was soon drawn into the emerging preservation movement, because she was appalled by the way London’s green spaces – she called them ‘out-door sitting-rooms’ – were being built over. Her housing schemes depended on having nearby ‘places to sit in, places to play in, places to stroll in and places to spend a day in’, yet with the pressures for new housing these were being gobbled up by voracious developers.

When the fields around Swiss Cottage were threatened with development she urged her influential friends to help her ‘save a bit of hilly ground near a city, where fresh winds may blow, and where wild flowers are still found and where happy people can still walk within reach of their home’. In the summer of 1875 she had persuaded the owner to sell the land to her if she could raise enough money. But after she had raised an astonishing £8,000 in three weeks he reneged on his agreement, leaving her in despair.

It was through this and other campaigns that she met the lawyer Robert Hunter, and through the Kyrle Society pursued the fight to save London’s open spaces. Hunter and Hill were a good campaigning pair. The diminutive Hill, less than five feet tall, was a compelling speaker and fundraiser. And increasingly alongside her was the sharp legal mind and experience of Robert Hunter, who had led the campaign to prevent common rights being extinguished as solicitor for the Commons Preservation Society.

Hunter was younger than Hill, born in 1844, and he was a delicate and studious child after contracting a near-fatal illness at two. A prodigy, he lapped up his formal education and became a scholar at University College, London, paying as much attention to social causes as to his studies, the reason for his attraction to the law.

In 1866, while an articled clerk to a firm of London solicitors, he spotted a competition sponsored by the businessman Henry Peek, seeking original essays on the subject of commons preservation. Peek (later an MP) was a common right-holder in Wimbledon where the common was facing the threat of enclosure by the Lord of the Manor, Lord Spencer. Hunter was young and untested and did not win the prize but his brilliant essay was one of six to be privately published by Peek, and before long he was articled to one of the Commons Preservation Society’s own lawyers, Philip Lawrence.

Sir Robert Hunter. (Courtesy of the National Trust)

The Commons Preservation Society had only recently been established (its 1865 foundation making it the oldest conservation group in England) but it was already forging a feisty reputation, fighting the enclosures that threatened to extinguish common rights and thereby allow London’s open spaces to be built on. The society became famous for its battles to save Wimbledon Common, Hampstead Heath and Epping Forest as spaces for public recreation. Hunter’s speciality, in which he delighted, was seeking out people who remembered common rights being exercised, and bringing them before the courts to testify that the rights that owners and builders wanted forgotten were still valid. He also condoned the Society’s use of direct action, tearing down fences installed by landowners at Tooting, Knole and Berkhamsted, arguing in his essay that ‘any commoner whose rights are molested is clearly entitled to throw down the whole fencing or other obstruction erected.’

Hunter’s career took off and in 1882 he was appointed Solicitor to the Post Office, where he demonstrated the same intelligent, questioning and painstaking approach, winning respect for his integrity and commitment to public service. He was by now working with Octavia Hill, and their bitter disappointment over Swiss Cottage Fields was followed in the early 1880s by another, when they tried to save the site of John Evelyn’s former home and garden, Sayes Court in Deptford. Though his house had long ago been demolished and rebuilt, later being used as a workhouse, the garden bore traces of Evelyn’s work and was of immense historical importance. Evelyn’s descendant wanted to give the house and garden to the nation, but as Hunter (after an exhaustive effort to identify a legal means of safeguarding it) had to convey to Hill, there was no secure means of doing so. The chance to save Sayes Court was lost, and what remained of it was bulldozed after the Second World War.

Stung by these failures, Hunter and Hill concluded that there needed to be a body able to acquire and hold in perpetuity properties like Sayes Court and the green spaces that were so valuable to urban residents. This needed to be a legal entity (Hunter suggested a company) in order to protect the public interests in land and open spaces. Hill didn’t like the word ‘company’, feeling that it spoke too much of business. Instead she suggested a trust, perhaps ‘Commons and Gardens Trust’? Hunter memorably pencilled across her letter ‘?National Trust. R.H.’

That was in 1885, a full ten years before the National Trust came into being. The impetus to get it off the ground was supplied by the firebrand campaigner Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley.

Rawnsley was the youngest member of the trio (born in 1851) and was also a devotee of Ruskin, having studied under him at Oxford. But he was no academic, and after going down from Oxford with a poor third-class degree he followed his father and grandfather into the church. He began work as an assistant in a hostel for down-and-outs in Soho. Ruskin referred him to Octavia Hill and she took him on as an assistant to one of her most devoted managers, Emma Cons. But Rawnsley drove himself too hard and suffered a nervous collapse, so Hill arranged for his convalescence with friends on the shores of Windermere.

Recovered, Rawnsley returned to work, this time in a mission for the poor of Bristol founded by Clifton College. Like Hill, he took poverty-stricken children for walks in the countryside and campaigned for open spaces for their recreation. He also saved the fourteenth-century church tower of St Werburgh from demolition. But his hot temper and outspoken defence of his badly behaved charges got him into trouble and he was dismissed. Jobless, and again helped by Hill, he was offered the living of St Margaret at Wray in the Lake District. And from there he began to campaign for the beauty of the Lake District, drawing on Wordsworth’s inspiration.

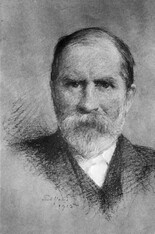

Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley in a 1915 pastel portrait by Frederick Yates. (Courtesy of the National Trust)

Rawnsley led the charge against the continuing ‘rash assaults’. It was not just intrusive railways and quarrying to which he objected: tourists, already numerous, flocked to the railway and threatened to disrupt the peace and harmony of the Lakes. The line to Windermere so decried by Wordsworth in 1844 had been built in 1847 and an estimated ten thousand day trippers visited Windermere on Whit Sunday 1883; many, ironically, attracted by Wordsworth’s popular Guide to the Lakes.

But neither tourists nor railways posed the most offensive assault on the Lake District. That came from a public body. The row was triggered by Manchester Corporation’s acquisition in 1877 of the Thirlmere catchment, followed by its application to Parliament for powers to construct a reservoir and take fifty million gallons a day by aqueduct to Manchester. Thirlmere was the central lake, the inspiration of poets and painters; it was the heart of this revered landscape.

Thirlmere before the reservoir was built. (© Martin and Jean Norgate)

The plans to dam the lake and flood the valley aroused huge opposition. It was orchestrated by Robert Miller Somervell, of the ‘K’ shoes family in Kendal, supported by the now famous defenders of beauty: William Morris, Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin, Octavia Hill, Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley. But as even they recognised, the moral case to supply clean water to Manchester was overwhelming and their combined efforts, which included stalling the Bill in the House of Commons for several months in 1878, failed to prevent the valley from being flooded. And its construction set in train further assaults on beauty: a new road (now the A591) was blasted through the heart of the Lakes and in 1908 the Corporation planted two thousand conifers, the first of millions, believing – extraordinarily – that native broadleaved trees would pollute the water supply.

The Lake District needed a watchdog and Rawnsley provided one. In 1887 he joined the protests against blocked footpaths to Latrigg above Keswick and argued the case for keeping ancient footpaths open. He fought off quarrying threats at Loughrigg, a dam across the river Duddon and ugly new roads around Thirlmere. His campaigns made him a local hero, and he was soon nicknamed the Defender of the Lakes. Before long he was the leading light of the Lake District Defence Society, which had grown out of the Thirlmere Defence Society to fight for the whole of the Lake District’s beauty.

The spring of 1883 saw Rawnsley’s instalment as Vicar of Crosthwaite, the parish church of Keswick. Here, in the heart of the Lake District, he was able to fulfil his ambitions for the revival of traditional crafts as well as the protection of landscape beauty. He and his wife Edith founded the Keswick School of Industrial Arts and the Ruskin Linen Industry (Ruskin had established himself at Brantwood, on Coniston Water, in 1872), providing a northern centre for the Arts and Crafts movement. And just as Beatrix Potter did later, Hardwicke Rawnsley threw himself into Lake District life. He was present at every show and sheep shearing, sports day and sheepdog trials. Passionately committed to teaching children about nature, he founded schools and a May Queen ceremony.

In 1889 Rawnsley topped the poll as an independent Liberal in the Keswick election for the new Cumberland County Council, mandating his defence of the Lake District. His friendship with Octavia Hill and Robert Hunter grew, and by 1893 he was attending regular meetings with them in London. That the National Trust was finally founded in February 1895 was due as much to Rawnsley’s energy, fuelled by his passion for the Lake District, as to Hill and Hunter’s greater experience.

The Trust’s founders, though, were always clear about their debt to Ruskin and were keen to remember him, especially in the hallowed ground of the Lake District. ‘One [place],’ wrote Hill, ‘which the years will we believe render always more valuable, [is] the simple stone erected to John Ruskin on Friar’s Crag at Derwent Water, where first he learned the beauty of that nature that he was to love so much and describe so eloquently.’

The Act which gave the Trust its legal standing also drew heavily on Ruskin’s vision, and confirmed the centrality of beauty to the Trust’s objectives:

The National Trust shall be established for the purposes of promoting the permanent preservation for the benefit of the nation of lands and tenements (including buildings) of beauty or historic interest and as regards lands for the preservation (so far as practicable) of their natural aspect, features and animal and plant life.

(National Trust Act, 1907)

Apart from the emphasis on beauty, the Act contains three significant phrases: ‘promoting’, giving the Trust a proactive energy; ‘permanent preservation’, requiring the foresight both to determine what merits preservation and the means to sustain it for ever; and ‘for the benefit of the nation’, confirming the social purpose of safeguarding beauty for everyone. By these words Ruskin’s passionate beliefs were given statutory force, and the universal right to beauty was recognised.

The Trust’s early priorities were not the great country houses and estates with which it is often associated today. Its leaders continued to safeguard vital patches of countryside as the cities sprawled, and rescued precious mediaeval vernacular buildings representing, in the Arts and Crafts movement’s words, ‘the twin virtues of beauty and utility; the value of craftsmanship, honesty and virtue’ as many were razed to the ground in the name of progress.

The Trust’s very first property was a gift from Fanny Talbot, a donor to Ruskin’s Guild of St George. She gave a little bit of land, Dinas Oleu above Barmouth, that would be forever open to the public. Its first building was Alfriston Clergy House: a mediaeval cruck house, almost falling down; it was purchased for ten pounds and the Trust commissioned the SPAB to restore it, confirming its commitment to the Anti-Scrape approach.

The acquisition and opening of Brandelhow in the Lake District, attended by Princess Louise, marked one of the National Trust’s early successes. Here it is pictured today. (Courtesy of the National Trust/Joe Cornish)

Although the National Trust was tiny, from the beginning its future looked secure. The founders were skilled at fundraising and winning support, and they populated its committees with members of the aristocracy, MPs and representatives of the great universities, ensuring advocacy for beauty in high places. Octavia Hill persuaded her friend Princess Louise, Queen Victoria’s daughter, to honour the ceremony marking the acquisition of the Trust’s first property in the Lake District, Brandelhow, in 1902. The National Trust became the place where thinking and prominent people came together to consider the state of conservation in the nation: what was under threat, what could be saved, what issues needed to be raised in Parliament, and what needed to be said to the press and the public. As a result, their legacy, like Ruskin’s, is far greater than the National Trust itself. It is about the principle and the importance of beauty, the right to defend what matters and the universal human need for beauty and places where it may be experienced.

These were the ideas and the spirit that gave birth to the fight for beauty; a fight that would continue undimmed into the twentieth century.