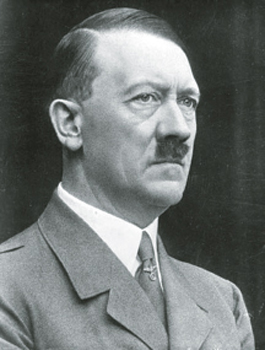

Adolf Hitler at the height of his power. (National Archives)

When I entered the back room in the Swiss bank, and turned the pages of those volumes, my doubts gradually dissolved. I am now satisfied that the documents are authentic.

—Sir Hugh Trevor-Roper, British historian and Hitler biographer

The atmosphere in the bunker had grown increasingly tense every day since the celebration of the führer’s birthday on April 20. The regular afternoon conferences in the narrow hallway outside his suite reflected the unrealistic nature of the situation. The führer’s advisers became increasingly frightened of reporting the collapsing situation that was rapidly taking place all along the Russian front. As the Red Army moved closer toward Berlin, Hitler deployed his phantom armies that even if they were at full strength would be no match for the Russian assault. It was time to begin taking steps to flee the bunker and Berlin for the Alpine Redoubt in the Bavarian Alps. Only from here would a last stand be possible. Virtually all of Hitler’s generals were urging him to transfer his headquarters before it became too late. When the subject was broached Hitler did not refuse; he merely put off further consideration until later, leaving his staff with some hope of getting out of Berlin before the Russian ring closed, sealing them inside with no hope of escape. The thought of capture by the Russians was unthinkable.

On April 23, Albert Speer, Reich minister for armaments and war production, made one last visit to the bunker to see his old friend. Opposed to Hitler’s scorched earth policy, Speer felt he owed it to Hitler to pay his respects to the man who gave him so much. Hitler loved Speer. He held him in esteem above all his other advisers. He felt they shared a kindred love of art and architecture that none of the others could understand. Only Speer shared this precious bond with him. Now Speer was going against Hitler’s orders to reduce the countryside to a blackened desert. Speer had made arrangements to save as much of the infrastructure as possible following defeat. There was still a nation of people to feed and care for. The devastated country would need rebuilding. Hitler knew of Speer’s “treason,” and yet he forgave him, unlike so many others he ordered shot. When Speer left on the morning of the 24th, there were no more decisions to be made. The only thing left was to secure as many of Hitler’s important papers as possible for future posterity. It was important that some record remain explaining the man and his dream. If there were to be a future Reich it would need his legacy to build upon. His personal papers would form that legacy.

A short distance from the opening of the emergency exit into the Reich’s Chancellery garden a tall, handsome man dressed in a green wool uniform with several ribbons on his breast stood near a large metal drum, watching the flames dancing around the opening of the makeshift incinerator. Two Wehrmacht privates struggled to lift a heavy box containing loose papers. The officer stared into the swirling flames, his attention drawn to the changing colors of the fire as it slowly consumed the mass of material the two men were feeding into the opening at the top of the drum. They had been ordered to systematically clean out all of the papers not chosen to make the trip and burn them. The officer watched intently, making sure none of the papers escaped the fire and that every last scrap was surrendered to the flames. After the last papers from the crate were gathered up by one of the men and tossed into the funereal pyre, the officer followed the soldiers with his eyes as they walked back toward the opening in the concrete tower.

A short distance from the fire a beehive of activity was taking place around another set of papers. Bodyguards were hurriedly loading Hitler’s personal papers aboard lorries to take them to an airfield near Berlin. From there they would be flown to the safety of the redoubt, where the final stand would take place. Two lower echelon soldiers that normally worked as personal valets struggled with several large, metal trunks that they loaded onto one of the lorries from the Chancellery garage. The trunks contained the personal property of Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun, Hitler’s mistress, soon to be his wife. The material was destined for Schoenwalde, located ten miles north of Berlin, where several airplanes sat waiting on the runway. There, the trunks containing Hitler’s papers were loaded into a Junkers 352 transport plane while another plane quickly filled up with personnel fleeing Berlin for Obersalzburg. They would accompany the sacred cargo and see to its safekeeping.

It was now only a matter of hours, thirty or forty at most, before Russian soldiers would begin breaking through the thinning German defensive lines and overrun the Chancellery and its grounds that shielded the führerbunker. The inevitable was close at hand.

While several individuals planned their escape, others planned their suicide. To their dismay, the führer finally announced his decision that he would remain in Berlin. He also made it clear that he would never be taken alive by the Bolshevik horde. He left specific instructions to his most trusted lieutenants to make sure his body and that of his new wife, Eva Braun, were cremated in the Chancellery garden so that no desecration of their corpses would occur. He still had abhorrent visions of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and his mistress, Clara Petacci, hanging upside down from a light pole in the town square of Milan while thousands of partisans danced around the swinging corpses, spitting on them and beating them with sticks and anything else they could find that served as a club. Partisans in the small village of Mezzegra had executed Mussolini and Petacci, then taken their bodies to Milan, where they were strung on meat hooks in the center of the city. Hitler would not allow such an end to come to him. He would die a Wagnerian death consumed in flames just as his Germany was now being consumed in flames.

His papers, however, would survive to tell the story of the building of the Third Reich and provide a blueprint for reestablishing the next. Although the current Reich had failed, it was not Hitler’s fault. He had not failed; those around him had failed. The German people had failed. All of the strong, loyal Germans were dead, leaving only the weak and unfaithful alive. These German people were not worthy of glory or survival. Only after complete destruction could a new Germany rise from the ashes of the betrayed Reich to finally conquer the world.

Despite his decision to remain in Berlin and die in the closing moments of the war he had created, Hitler ordered those still remaining with him to attempt a breakout. Operation Seraglio would see some eighty people and several trunks of important papers evacuated to the führer’s Alpine Redoubt near the mountain village of Berchtesgaden, Hitler’s favorite retreat. Here, in the mountains of southern Germany, the Nazis would establish a new command center and carry on the fight to the bitter end. Hans Bauer, Hitler’s personal pilot, was placed in charge of providing the fleet of ten airplanes and crews necessary for the escape. Major Friedrich Gundlfinger, a battle-hardened veteran of the Eastern Front, would pilot the plane carrying Hitler’s personal archive. It was essential that all of the planes take off and fly the 350 miles south under cover of darkness. The Allies controlled the air, and if the breakout were to be successful it had to take place at night.

Adolf Hitler at the height of his power. (National Archives)

Gundlfinger was charged with taking sixteen important Nazis in addition to Hitler’s private papers. But something had gone wrong, causing a delay. Gundlfinger was forced to wait until a few minutes before 5 a.m. before the last of the sixteen passengers was safely aboard. Somewhere south of Berlin, Gundlfinger was attacked by allied fighter planes. Within minutes the Junkers 352 was on fire and falling toward the earth. It crashed near the small German village of Boernersdorf, near the Czech border in western Germany. Its destination was Ainring, the closest airfield to the Nazi retreat at Berchtesgaden. When Hitler was told of the plane’s fate he was heard to howl like a wounded animal. According to Bauer, Hitler moaned, “I had sent extremely important documents and papers with him [Gundlfinger] that were to explain my actions to posterity. It is a catastrophe!”1 It would be eight years before the story of the plane’s crash and the recovery of twelve bodies would become known.2 It would be another thirty years before the fate of the “extremely important documents and papers” would come to light as the most sensational discovery of the postwar era. The contents of the crashed plane were ideal for the conspiracy that would surface years later.

A German Junkers 352 like one this was used to carry Hitler’s personal papers, including his alleged diaries. The plane crashed near the German village of Boernersdorf, killing all aboard and burning Hitler’s papers. The diaries were claimed to have been rescued by villagers. (Luftwaffenphotos)

The story behind the “discovery” of the Hitler diaries actually begins on April 30, 1945, the day Hitler is reported to have committed suicide. So powerful was the image of this world nemesis that stories of his survival flooded newspapers and magazines around the globe. First-person interviews told of his flight from the bunker to France, where he was working in a casino; to a monastery in the Swiss Alps, where he became a shepherd; to a cave in Italy, where he lived as a hermit; casting nets as a fisherman in the Baltic Sea or off the coast of Ireland. He was in Albania, Spain, Argentina, France, and Italy, even England, where the British were hiding him. So powerful were these preposterous stories of his outwitting the Allies that the British decided to launch an official investigation into Hitler’s final days. Code named Operation Nursery, the task was assigned to a British intelligence officer named Hugh Trevor-Roper, a young Oxford research student in history. The assignment launched Trevor-Roper on a career in history that would lead to his recognition as a World War II historian with impeccable credentials. In 1979 he was awarded a peerage and chose the title “Baron Dacre of Glanton.”3

According to Trevor-Roper, history is an art, in which the most important attribute of any successful historian is his imagination.4 The young historian undertook his new assignment with vigor, leaving no stone unturned in his quest for the truth behind Hitler’s last days as führer. Approaching his assignment like a research project in an academic institution, Trevor-Roper first compiled a list of all the known characters who were in the bunker with Hitler during his final days, including those who were there when the announced death took place. The list included forty-two individuals in all.5 He then set about trying to locate each of the individuals, and those he found he interviewed. At the end of his search he was able to reconstruct the events that took place during the final days and hours inside the führerbunker.

In the afternoon of April 29, Hitler had one of his cyanide capsules from his own personal stock tested on his favorite Alsatian dog, Blondi. The dog died instantly, satisfying Hitler that cyanide was both effective and quick. Later that evening he asked to say good-bye to the women working in the bunker. Having personally shaken hands with each of the ladies, Hitler retired to his private quarters. He appeared subdued and spoke only when necessary. The following morning, April 30, he lunched with two of his secretaries and his cook. Eva Braun remained in her room alone. After lunch, Hitler held his final farewell ceremony in the outer corridor to his suite. Eva Braun joined him this time. Martin Bormann, Wilhelm Burgdorf, Joseph Goebbels, Otto Guensche, Walter Hewell, Peter Hoegl, Hans Krebs, Heinz Linge, Werner Naumann, Johann Rattenhuber, and Erich Voss were present, along with Hitler’s four devoted women secretaries, Gerda Christian, Gertrude “Trudl” Junge, Else Krueger, and Constanz Manzialy. Following their good-byes, Hitler and Braun retired to Hitler’s small living room. A few minutes later a single pistol shot was heard.

Heinz Linge was ordered by Hitler to wait ten minutes and then enter the room.6 Linge opened the door and entered, followed by Bormann, Guensche, Goebbels, and Artur Axmann, who had joined the group after Hitler and Eva said their good-byes. Linge, Axmann, and Guensche survived the war and years later gave separate interviews confirming the deaths of Hitler and his wife, Eva.7 Axmann told of examining the bodies minutes after death. Linge wrapped Hitler’s body in a blanket and turned it over to two SS guards, who carried the body up to the Chancellery garden area. Linge then carried Eva Braun’s body up, and they both were laid in a bomb crater. Hitler’s chauffeur, Hans Kempka, secured several cans of petrol from the motor garage and dowsed the bodies with gasoline. Guensche dipped a rag into petrol and, lighting it, tossed the burning rag into the crater onto the gasoline-soaked bodies. A roar of flame leapt from the hole and the funeral pyre lit the surrounding area as several of the Hitler faithful stood at attention and gave the stiff-armed Nazi salute. Over the next few hours the corpses were repeatedly dowsed with petrol to keep the fires burning until nothing was left but a few bones and ash. Surviving the fire were Hitler’s dental plates, pieces of jawbone with teeth, and a skull fragment containing what appeared to be a bullet hole. The dental plates were later used by the Russians to confirm that the bodies in the crater were those of Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun Hitler. The Russians eventually released their forensic findings, even though many in Russia, including Joseph Stalin, believed that Hitler had escaped the bunker.

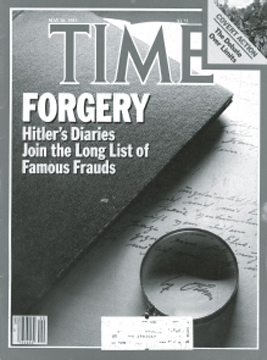

Trevor-Roper’s study was accepted by the Western world as a masterful piece of detective work that concluded that Hitler died as originally stated, by his own hand in the bunker on the afternoon of April 30, 1945. Trevor-Roper’s report eventually became a best-selling book titled The Last Days of Hitler, and it remains in print to this day.8 The young history studentintelligence officer made quite a name for himself by his thorough and systematic work in proving Hitler died in the bunker. Of course, the evidence produced by Trevor-Roper was circumstantial, all of it based on individual statements gained through interviews. The forensic evidence did not emerge until later and then was based exclusively on a comparison of the dentition found in the ashes of the bomb crater to records from Hitler’s dentist. There was no way at the time to prove the skull fragments recovered along with the dentition came from the same person.9

Despite Trevor-Roper’s careful work, rumors continued for several decades that Adolf Hitler escaped and took up residence just about everywhere imaginable, positioning himself for the inevitable comeback when the British and Americans engaged the Soviet Union and its puppet states in the ultimate war for worldwide supremacy.

Following Hitler’s death in the bunker, his mystique lived on, and has even grown over the decades. His malevolent personality has a magnetic power that draws many people toward it, and those who get too close become pulled into its evil center.

Hitler knew how to appeal to people’s inner souls. He adorned his Third Reich with a cornucopia of pageantry and pomp that dazzled the eye and swelled the heart with nationalistic pride. The pageantry and pomp covered up the extreme acts of brutality carried out under Hitler’s orders. It was not so much the individual acts of brutality that would shock the world; it was the scope of the brutality. The magnitude was unfathomable to the average person. And it was all being carried out on behalf of one man, Adolf Hitler. For Adolf Hitler was Germany, and Germany was Adolf Hitler. The Germans had a saying for it: Ein Volk, Ein Reich, Ein Fuhrer. One People, One Empire, One Leader.

Hitler’s personality was so strong that it still casts a shadow more than sixty-five years after his death. There are reported to be over fifty-five thousand items in the British Library and Library of Congress relating to Hitler and the Second World War. On the one hand, there are books about nearly every aspect of his life and death, including his birth, youth, health, psyche, pleasures, hates, eating habits, personal security, art, sexual attitudes, and humor or the lack thereof. There is even a book devoted to his conversations during dinner.10 There are personal accounts written by his valet, pilot, doctor, photographer, chauffeur, ministers, and generals.11 And despite this plethora of writing the man remains an enigma.

Many European countries have enacted various laws prohibiting the display of Nazi symbols of any sort. The attempt to destroy Hitler’s bunker where he spent the final days directing his hopeless war and ended his life on April 30, 1945, has only added to the mystique of the man. The market for Nazi memorabilia remains as strong as ever, as some people want to own a piece of the evil empire, keeping its memory alive, while others just want a piece of one the most interesting and dangerous periods of our history. Perhaps this is why the world so readily accepted the discovery of his private diaries that purported to give an insight into his innermost private thoughts.

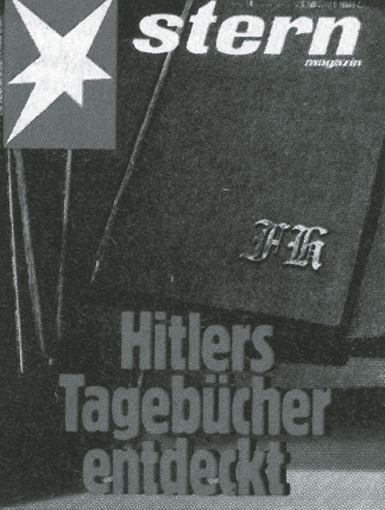

The “discovery” of the Hitler diaries was almost an accident, as their creator never intended for them to become known outside a narrow collecting community. The story begins with the journalist Gerd Heidemann, who brought them to the attention of his publisher at Stern magazine. Heidemann was an unusual sort of journalist whose ability to convince his employer to keep him on the payroll is almost a story in itself. It is important to understand that Heidemann didn’t discover the Hitler diaries; he merely learned of their existence and eventually persuaded their owner (creator) to sell them to Stern magazine. Just how Heidemann was able to accomplish this began in the mid-1950s, when he was given an assignment to dig up information about the Nazis, the Third Reich, and Nazi war criminals. Although the project generated little interest to his editor, it exposed Heidemann to the intriguing underworld of the Nazi Party. New assignments came and went, and each project was marked by Heidemann’s obsessive nature. Once into a subject, he set about to systematically collect everything remotely connected to the project. His weakness was that he did not know when to stop or how to organize his material into a cohesive story, separating the important and relevant data from the chaff. It was not unusual for his editors to take his raw material, including his notes, and assign the final writing of the story to a more skillful writer on Stern’s staff.

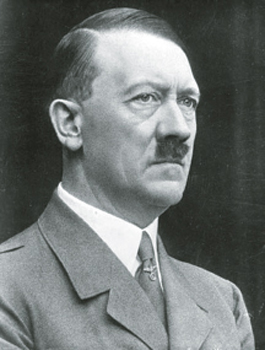

Produced from an unpublished manuscript of Hitler’s conversations during dinner, Hitler’s Table Talk was not subject to the copyright law, unlike Mein Kampf and other Hitler assets. Hugh Trevor-Roper wrote the preface. (Author’s collection)

The key that unlocked Heidemann’s “discovery” of the Hitler diaries stemmed from his attempt to discover the real identity of the famous German mystery writer “B. Traven.” While still obsessing over Traven long after his research had been published in an article in Stern, Heidemann stumbled across the Carin II, the ninety-foot yacht that had been presented to Nazi Luftwaffe head and Hitler confidant Hermann Goering. The badly worn yacht was sitting in her slip along the waterfront of the West German capital of Bonn. It was for sale by its present owner, who wanted to get rid of the financial liability of maintaining it. The cost had become too much. It was love at first sight for Heidemann, and his impulsiveness resulted in his purchasing the yacht. He mortgaged everything he owned and soon found that the cost of repairs and upkeep was well beyond his means as a journalist. Nonetheless, he was convinced that the derelict could be restored and later resold for a huge profit. Along the way he met Edda Goering, daughter of Hermann Goering, who helped turn the yacht into a floating museum of Goering memorabilia. With Edda’s help, Heidemann began making friends with former Nazi figures, including those who had held privileged positions in Hitler’s inner circle—such figures as SS General Wilhelm Mohnke, who commanded the defenses of the Reich Chancellery, and SS General Karl Wolff, Heinrich Himmler’s liaison officer with Hitler and commander of SS police forces in Italy. Before long, Heidemann was hosting parties aboard the Carin II for major Nazi figures who sat atop the pinnacle of the Third Reich. It did not take a great deal to draw Heidemann into the lure of the Nazi mystique.

Shortly after Heidemann purchased the Carin II he, too, realized how costly the yacht was in needed repairs and maintenance fees and began looking for a buyer. His search led him to a prominent Nazi memorabilia collector by the name of Fritz Stiefel. Heidemann visited Stiefel at his home in the Stuttgart suburb of Waiblingen. He first tried to sell Stiefel the yacht, but Stiefel was not interested. Next, Heidemann offered Stiefel a partnership share in the Carin II, but again Stiefel turned Heidemann down. Still not ready to admit defeat, Heidemann offered Stiefel several artifacts from the Carin II that belonged to Goering and carried the Goering crest. Stiefel was interested and bought several artifacts for his collection. It was at this point that Heidemann brought up the diary that belonged to Hitler. Heidemann was obsessed with the idea that Hitler actually kept a diary. He pressed Stiefel to see the diary. Stiefel was still unsure of Heidemann and hesitated at first, but Heidemann’s persistence finally paid off. Stiefel agreed to show him the diary.

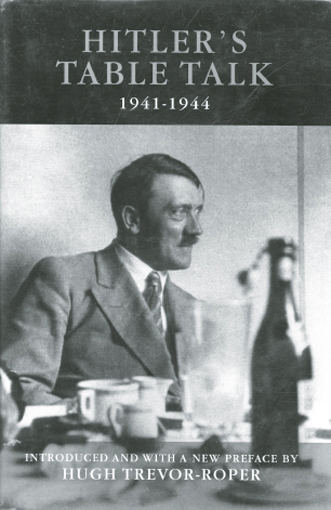

Hermann Goering’s private yacht, Carin II, named for his first wife. (Author’s collection)

Stiefel led Heidemann to the basement of his house, where he had a special room whose entrance was guarded by an armored door. Just beyond the door was Stiefel’s personal museum of Nazi memorabilia displayed in elaborate glass cabinets and neatly arranged on shelves. It was a treasure trove unlike anything Heidemann had ever seen or even imagined. After the reporter had taken in the incredible collection, Stiefel handed Heidemann the holy of holies, a large bound book with black covers bearing what appeared to be the initials “AH” in gothic letters.12 Heidemann immediately realized the significance of the book. It was potentially the find of the century. Where did Stiefel get it? Were there others? Stiefel told Heidemann that he purchased the diary from a man who lived in Stuttgart who had acquired it from a relative who lived in East Germany. Stiefel believed there were as many as twenty-six such diaries. Heidemann was stunned. Twenty-six diaries? Heidemann pressed Stiefel for the man’s name. Stiefel refused, telling Heidemann that the man insisted on strict anonymity. Anonymity was not necessarily a red flag. It was not unusual for the owners of extremely rare and important objects to remain anonymous to the general public. It was a form of protection from the curious.

When Heidemann returned to Hamburg and Stern magazine, he was beside himself as he tried to explain the incredible feeling of having actually held the diary of Adolf Hitler. Incredible. Here was the publishing find of the century, perhaps of the millennium. A diary in Hitler’s own hand—and there were more, lots more, as many as two dozen more. Think of the history contained in those diaries. Think of the insight into the mind of the man who conquered Europe and changed world history forever. The diary, however, came not from the mind of a madman, but rather from the mind of a minor forger.

Born in 1938 in Saxony (later East Germany), Konrad Paul Kujau was one of five children. His father was a shoemaker who became an enthusiastic supporter of Hitler and the Nazi Party. By the time Kujau was a teenager he had developed a strong interest in all things Nazi. His father had been killed in 1944, plunging the family into poverty. Separated from his siblings, Conny, as his family and friends knew him, wound up in a refugee camp. At age nineteen he was resettled near the city of Stuttgart, where he became involved in a series of petty crimes. He was arrested and convicted of forging several dozen luncheon vouchers and sentenced to five days in prison. It was the first of several scrapes with the law. Over the next twenty years Kujau tried his hand at various servicerelated businesses, most of which failed. It seems he could not keep from engaging in a variety of criminal activities, albeit petty in nature, which resulted in a lengthy criminal record. Throughout this period he adopted several aliases in an attempt to avert detection by the legal authorities. In 1970, Kujau and his common-law wife, Edith Lieblang, took up a new enterprise, one that reflected Kujau’s lifelong interest in Nazi militaria. East Germany was a veritable treasure trove of German and Nazi artifacts that survived the war. It was not difficult to find items at modest prices and smuggle them across the border into West Germany, where a thriving black market flourished. By 1974 the selling of Nazi memorabilia had taken over Conny and Edith’s lives.

While Kujau made a satisfactory living dealing in Nazi artifacts, he was not satisfied. He wanted to do something big. Something that would gain him the attention and respect he craved. The demand for Nazi memorabilia was so strong that collectors applied rather low standards in accepting provenance. Some pundits quipped that if Hitler had actually had all of the Nazi memorabilia available to him during the war that currently existed in the marketplace he wouldn’t have lost. For many highly collectible artifacts of war, whether from the American Civil War or World War II, the line between authentic, reproduction, and outright fabrication becomes quite blurred. When Confederate flags and belt buckles began to escalate in price to incredible heights, skillful fakes (or reproductions) quickly followed. When the demand for Nazi memorabilia began to outstrip supply, the same phenomenon occurred.

Konrad Kujau was rather expert at exploiting such markets. By his own admission, Kujau “stumbled” into his forgery habit when he decided to use his acquired expertise about Hitler and the Third Reich to write a book.13 In his own way of thinking, it was a small step from writing a book to forging a diary.

Heidemann was overcome with the idea that Hitler had produced as many as two dozen diaries detailing his rise to power and rule over the Third Reich. He became convinced that the editors at Stern were about to come into the greatest story of the magazine’s existence. But, much to Heidemann’s surprise, the editors at Stern, Henri Nannen and his deputy, Peter Koch, were not interested in Heidemann’s story. They even forbid him to continue to follow his leads to the rest of the diaries, telling him to drop his crazy infatuation with Nazi history and memorabilia. They were skeptical that such a trove of material existed. Stunned at first, Heidemann was undeterred. He decided the story was too good to ignore and went to see Thomas Walde, the head of Stern’s history section. He told Walde about Stiefel and the diary. Walde, unlike Stern’s editors, became intrigued and told Heidemann to go ahead and pursue the story but to keep it secret from Nannen and Koch. Walde was taking a risk, but like Heidemann, he believed there was the potential for a blockbuster story if true.

Still unable to get Stiefel to reveal his source, Heidemann put his research talents in full gear and decided to begin at the beginning. Having read the story of the ten trunks of special papers flown from the bunker in a Junkers 352 piloted by Major Gundlfinger and its crash somewhere near Boernersdorf, near the Czech border, Heidemann began tracking the possible flight path in hopes of verifying the story. He not only discovered that a plane fitting the description of the document plane did indeed crash near Boernersdorf, but actually located Gundlfinger’s grave and those of the other passengers known to be on the flight. Now convinced that Heidemann was on to something big, Walde told him to go all out on the story.

Stern’s reporter Gerd Heidemann posing next to the graves of two crew members of the Junkers 352 flight that crashed near Boernersdorf. (DPA)

Heidemann, in anticipation of convincing Stern’s owners, put together a dossier containing the results of his investigation. Included was a description of the missing flight with the several trunks containing Hitler’s most select documents from the bunker, the crash site of the plane, the location and photographs of the graves of the pilot and other passengers on the illfated flight, and Heidemann’s description of the diary Stiefel had allowed him to examine.

But Heidemann and Walde were not ready to go to their editors, Nannen and Koch. It was Koch who angrily told Heidemann not to spend any more time or expense money on his crazy Nazi projects. Instead, the two men took the dossier and their story to Manfred Fischer, the managing director of Bertelsmann, the media conglomerate that owned Gruner & Jahr, the publishing company that published Stern. Walde and Heidemann essentially went over the heads of their bosses and went straight to the man that controlled the parent company of Stern. Fischer was intrigued, and understood the situation between Heidemann and Koch. Fischer, who was scheduled to take over managing the parent company that owned Stern, did not like Koch.14 He approved the project and authorized 200,000 marks in cash, giving Heidemann the necessary funds to begin negotiating with the owner of the alleged diaries. But Heidemann still had to physically produce the diaries, and to do so he had to track down their mysterious owner.

Stiefel, the owner of the lone diary that Heidemann had seen, refused to give him any information about the owner of the other diaries. Heidemann decided to contact Jakob Tiefenthaler, the man who first told him about Stiefel and the Hitler diary. Back when Heidemann was desperately trying to sell the Carin II and get out from under the growing debt the yacht was costing him, General Wilhelm Mohnke put Heidemann in touch with Tiefenthaler as someone who had significant contacts among Nazi collectors and might be able to help Heidemann sell his yacht. During the course of their efforts to sell Carin II, Tiefenthaler told Heidemann about Stiefel and his diary. Heidemann decided to flush out the owner of the diaries in a bold, unauthorized move. He told Tiefenthaler that he could guarantee a payment of 2 million marks (approximately $600,000) in either cash or gold to the secret dealer that had possession of the Hitler diaries.15 If that wouldn’t draw him out, then nothing would work. In addition, Heidemann said that Stern would protect the owner and guarantee his anonymity, using the universal right of a journalist and his paper not to divulge the source of their information.

After seven weeks, Tiefenthaler finally got back to Heidemann. The owner, a militaria dealer named Fischer from Stuttgart, was interested. Tiefenthaler gave Heidemann the man’s telephone number and the address of his antique shop in Stuttgart. Heidemann, as obsessive as ever, flew to Stuttgart without contacting Fischer ahead of time and drove to the address of the antique shop, then waited. When Fischer failed to turn up, Heidemann drove to the suburban area where Fischer lived and called the number Tiefenthaler had given him. Fischer gave Heidemann his address and told him to come ahead. He had agreed to meet with Heidemann.

The cat was close to jumping out of the bag. Heidemann’s dogged persistence had finally paid off and he was about to meet the owner of the infamous Hitler diaries. Now he had to convince the owner to show him the diaries and then to sell them to Stern. Only when he had all of the diaries in hand, or at least an agreement to buy the rest of the diaries, would he feel comfortable with going to Stern’s editors—the very editors who had forbidden him from pursuing any more of his “crazy Nazi stories.” Heidemann was confident, however, that once they learned of the cache of extraordinary diaries they would do an about-face.

Mr. Fischer, it turned out, was an alias. Fischer’s real name was none other than Konrad Paul Kujau. He made his living by selling mostly bogus Nazi memorabilia to a few fanatic Nazi collectors like Fritz Stiefel. As long as he was able to sell to private collectors who wanted to remain anonymous, he was relatively safe from discovery. Selling to a magazine like Stern was taking on a serious risk of being exposed, especially if the money involved was in the millions of marks. Surely Stern would call on experts to authenticate the diaries and other Hitler items Kujau had produced, and it wasn’t clear the diaries would pass expert scrutiny.

Kujau’s other problem was that he had a nefarious past that included two convictions for forgery, and several petty crimes under a string of aliases, which landed him in prison. Kujau’s fascination with military memorabilia eventually had resulted in his becoming a dealer in Nazi artifacts. It was a relatively easy way of making money and proved to be lucrative. Dealing in genuine articles at first, it didn’t take long before Kujau’s larcenous character emerged. With his artistic talent he could produce an endless supply of highly sought-after artwork that he could sell at high prices. Producing fake artwork soon led him into forging documents. By mixing forged documents in with real ones imported from East Germany, he was able to keep a steady supply flowing through his shop, to his customers’ delight. He was good at his trade, and his knowledge of the Third Reich served him well.

Kujau soon mastered Hitler’s handwriting and his style of painting. Hitler was a prodigious artist who turned out between two thousand and three thousand various works of art, including sketches, watercolors, and oil paintings.16 The abundance of material made it a good deal easier for Kujau to fabricate Hitler’s works and pass them off as originals. He became so well known as a dealer in Hitler and Nazi memorabilia that his clientele spread to the United States, where he regularly supplied customers with his forgeries. Fritz Stiefel soon became one of Kujau’s best customers, having spent over 250,000 Deutschmarks (approximately $75,000) for memorabilia from Kujau’s “collection.” Among Stiefel’s prized possessions was a manuscript copy of 233 pages of Mein Kampf written in Hitler’s hand. Kujau had forged the manuscript copy of the infamous book as a way of practicing Hitler’s handwriting.17 He was so pleased with the result that he had no hesitancy in passing it off as authentic. Stiefel’s passion for Hitler memorabilia blinded him to Kujau’s forgeries.

One of hundreds of authentic watercolor paintings by Adolf Hitler. Kujau produced several fake Hitler paintings that successfully fooled collectors. (U.S. Army)

Precisely when Kujau decided to forge a Hitler diary is difficult to determine. He gives various versions of how it all began. In one version he decided to put his considerable knowledge of Hitler to a more productive use by writing a legitimate biography of the führer. He soon realized that developing the biography as a diary (or diaries) was even more productive. In another version, Kujau typed out a chronology of Hitler’s life for the year 1935 using a Nazi Party yearbook. When he finished, he decided to transcribe it in Hitler’s handwriting to see if he could replicate it. Using one of several notebooks he had purchased to catalogue his own collection, Kujau converted the chronology into diary form. Once again he was so pleased with his effort that he showed the book to Fritz Stiefel, telling him it was a Hitler diary. Perhaps he wanted to see Stiefel’s reaction as a test of how well he had made the copy. Stiefel examined the book carefully and asked Kujau if he could borrow it. Kujau suspected that Stiefel wanted to purchase the diary and needed to physically possess it for a period of time before striking a deal. Stiefel then did what any competent collector would (or should) do: he sought the opinion of an expert on Hitler’s writing, August Priesack. Priesack worked as an art historian from 1935 to 1939 in the Nazi Party main archives under the direction of Hitler’s second in command, Rudolf Hess. Surviving the war, Priesack made a living by representing himself as an authority on Nazi art, including that produced by Hitler.

Stiefel invited Priesack to view his collection of memorabilia. Priesack was impressed, and told Stiefel his collection was of “great historical significance.”18 After examining the diary he declared it authentic.19 Kujau was ecstatic. Previously, his forgeries had only been inspected by amateurs, whose expertise came from owning bits and pieces of Hitler memorabilia, much of it fabricated. Impressed with Stiefel’s collection, Priesack contacted Eberhard Jaeckel, a professor of modern history at Stuttgart University. Like Priesack, Jaeckel was impressed with Stiefel’s collection and later gave his blessing to Kujau’s diary, urging him to seek out others. Kujau must have been both confused and elated. Having plied his forgeries on collectors whose expertise was limited, he had just received the approval of his forgery by two leading experts on Hitler documents and paintings. It was too good to be true. Once again, wanting to believe apparently blinded the so-called Nazi experts.

Kujau gained increased confidence. If two of the leading experts on Hitler accepted his forgeries, surely others would, too. He was no longer afraid of his work being examined by others outside the narrow group of private collectors he normally dealt with. And, 2 million marks were beyond his wildest dreams.

But more than the money, it was Goering’s uniform that caught Kujau’s attention. Kujau had acquired the uniforms of several of the top Nazi leaders, including Hitler, Himmler, and Rommel, but not Goering. The uniform Heidemann had on the Carin II was the clincher that brought Kujau over to the journalist’s side. Unknown to both Heidemann and Kujau, the uniform was bogus, a reproduction that Edda Goering had ordered and given to Heidemann to display on the yacht along with other memorabilia. It was fitting that the master of fakery was now himself taken in by a fake uniform. Poetic justice perhaps?

Kujau was now willing to deal. There was only one problem, a small one to be sure. There were no other diaries. The diary Stiefel was holding in his special “vault room” was the only diary Kujau had forged. He was confidant, however, that he could produce more. He just needed time. Kujau told Heidemann that his brother, an East German general, was the go-between with the peasant farmer who had liberated the precious cargo from the downed plane, but that he could not afford to jeopardize his career or life by revealing his role in acquiring the diaries. The diaries would have to come out of East Germany slowly, one at a time. Kujau hoped that this ruse would buy him the time he needed. Luckily, he was prolific. He was able to work from early morning through evening nonstop, and he loved his work, which was a necessary requirement if he was to pull off the greatest hoax in Hitler memorabilia.

Kujau went to work writing new diaries. In the meantime, Heidemann returned to the Stern offices in Hamburg. It was time to decide where to go next in convincing the magazine to go with the story of the Hitler diaries. Heidemann began to worry that news of the diaries would soon get out and that another news organization might step in and pull the discovery out from under him. He suddenly felt the necessity of getting Stern’s editors to act and act quickly. Heidemann’s problem was that he could not go to Nannen and Koch, who had forbidden him from involving himself in more Nazi “crap,” as Nannen so brusquely put it. Heidemann would have to continue to work around the two editors and go over their heads. Meanwhile, Kujau had his first major scare concerning his other forged documents.

One of the items Kujau sold to Fritz Stiefel was a poem allegedly written by Hitler in 1916 (and so dated) that had actually appeared in the published work of German poet Herbert Menzel in 1936.20 Eberhard Jaeckel, the history professor and expert on Hitler writings, had previously published a book on Hitler’s writings and included several pieces from Stiefel’s collection of Kujau forgeries, including the poem. When another professor of contemporary history called the strange anomaly to Jaeckel’s attention, he concluded that the poem in Stiefel’s collection was a forgery. Stiefel asked Kujau to explain. Kujau, always verbal, launched into a detailed description of the attempt to transfer Hitler’s papers to his Alpine Redoubt in Berchtesgaden. He told of the plane’s crash and how local peasants found several trunks in the wreckage. He ended by pointing out that he was only the go-between, receiving the material from his brother, who was purchasing it from the people who recovered the cache of documents from the crash site. What could he do? In essence, Stiefel was being told he was stuck with the forgery through no fault of Kujau’s.

Jaeckel would have to publish a correction to subsequent editions of his book. Surprisingly, the discovery of a forgery did not send up any red flags or compromise the pending deal on the diaries. Heidemann, for one, was so overwhelmed by the thought of the Hitler diaries that nothing was going to deter him from moving forward as fast and as hard as he could. Heidemann had everything to lose and nothing to gain by having the deal fall through. Kujau, on the other hand, had a great deal of writing to do. His diaries had to cover thirteen years of Hitler’s incredible life as he set out to conquer the world.

Returning to his home in Ditzingen, he threw himself into his project. From early morning through late evening Kujau worked on creating new diaries. He drew on every imaginable source for material, including his extensive library of Hitler books, newspapers, Nazi Party newsletters, and his Nazi friends who were close to Hitler during his reign as führer. Like so many successful forgers, Kujau possessed an extraordinary knowledge of his subject. Trying to convince the experts at the level of forgery Kujau was attempting took a very special talent. Working day and night, Kujau finally completed three of the diaries. He was ready for the next installment in this crazy episode that Heidemann insisted on carrying forward.

Over the next several months Heidemann visited Kujau and received the latest set of diaries “smuggled” out of East Germany by Kujau’s fictitious brother. The story that the diaries had to be smuggled out of East Germany, a communist police state, helped Kujau pull off his scam. It gave him time, and it gave him the perfect cover for not revealing his sources.

When Manfred Fischer took over the managing directorship of Bertelsmann, the parent conglomerate that controlled Gruner & Jahr, Stern’s publisher, he became senior to Nannen and Koch, Heidemann’s nemeses. When Fischer assumed the management of Bertelsmann, Gerd Schulte-Hillen, an engineer who had been overseeing the printing operations of Gruner & Jahr, was picked to take over managing that firm. Fischer took Schulte-Hillen into his confidence and told him about the documents flown out of Berlin only to wind up in a plane crash near Boernersdorf. Fischer went on to tell Schulte-Hillen that he had already committed nearly a million and a half marks to the project and that Heidemann had obtained several of the diaries. The inner circle of those who knew about the transactions had now grown to seven: Gerd Heidemann, Thomas Walde, Wilfried Sorge, Jan Hensmann, Manfred Fischer, Peter Kuehsel, and Reinhard Mohn, all sworn to secrecy. It was time to bring Stern and its editors on board with the plan to acquire and publish the diaries.

Nannen had stepped down as one of Stern’s editors to take over the day-to-day publishing of the magazine. Felix Schmidt and Rolf Gillhausen replaced him. On being informed about the clandestine activity of Heidemann behind his back, Koch was enraged, but there was little he could do. The owners of the parent company, Manfred Fischer and Reinhard Mohn, had decided to go ahead with the project at all costs. Having the leaders of Stern on board—or more accurately, in line—Fischer became concerned about an interesting question. Who owned the copyright to Hitler’s diaries and other writings? It was an intriguing question. Could a monster war criminal like Adolf Hitler own the copyright to his writing? And if so, could he pass it down to next of kin? Could Stern legally publish the documents without approval? But approval from whom? Fischer called in Gruner & Jahr’s legal adviser, Andreas Ruppert, and set him to work finding out the answers to these intriguing questions. Did the führer have any legal rights to his writings? Incredible as it sounds, he did. A lawyer had been hired by Hitler’s sister Paula to represent her and other family members in dealing with Hitler’s estate. Interestingly, Hitler was still owed 5 million marks in royalties from his publisher for Mein Kampf. In another strange quirk of law, while the state confiscated the money and certain artifacts Hitler had given to his housekeeper, it was prevented from stopping publication of another Hitler manuscript, titled Hitler’s Table Talk, 1941–1944, compiled by Hitler and later edited by several authors, including Hitler historian Hugh Trevor-Roper, who wrote a preface to the book.21 The law, it seems, applied only to already published manuscripts, but not to unpublished manuscripts.22 The same ruling applied in 2006 to a newly discovered authentic Hitler manuscript written as a follow-up to Mein Kampf. Titled Hitler’s Second Book, it was edited by German scholar Gerhard Weinberg.23

It turns out that German historian Werner Maser had negotiated a contract with family members to act as trustee for the Hitler heirs. Heidemann, taking the bull by the horns, tracked down Maser. After some negotiating, the two signed a contract giving Heidemann the sole rights to all “discovered or purchased documents or notes in the hand of Adolf Hitler.” Maser received a fee of 20,000 marks, in cash.24 All of the transactions that occurred throughout the entire episode were made in cash, suggesting distrust among all of the parties involved.

As the volumes began to accumulate, from a few at first to over sixty, Manfred Fischer decided it would be prudent to move the diaries to a special safe-deposit box in Switzerland to protect them from possible theft. In reality, it seems more likely that Fischer was fearful the West German government might step in and confiscate the diaries even though they represented unpublished material. The West German government had a strong aversion to anything Nazi and went to great lengths to suppress Nazi artifacts, including the confiscation of Nazi material.

While Kujau labored away at forging the diaries, allotting each book a six-month period in the Nazi leader’s takeover as führer, Gerd Heidemann was arranging to withdraw large sums of money to pay for the diaries as they were “smuggled” piecemeal across the border from East Germany. Kujau was disciplined in his approach and was able to satisfy his victims despite the urgency they felt in wanting to acquire all of the diaries as quickly as possible. Since they needed to be created, they would have to be patient. Believing each diary was a separate negotiation, and required a separate plan for smuggling it across the East German border, the Stern team had no alternative but to rely on Heidemann, who had to rely on Kujau. Kujau could complete the writing of each diary in four to five hours, but the overall time it took him to create a diary was several days because of the research he had to do in creating the journal. Using his extensive library of Nazi books, newsletters, and newspapers, Kujau could focus on a particular period in Hitler’s reign and complete a diary with reasonable accuracy. As pressure built to deliver more diaries faster, Kujau hurried his research, resulting in errors working their way into his writing. The errors should have been picked up by the experts, but they were missed in the early days of inspection. Only in hindsight did many of the experts acknowledge the diaries were forgeries.

As the number of diaries delivered by Kujau passed the two dozen mark, Thomas Walde, Stern’s editor in charge of history, decided it was time to have handwriting experts analyze the material. Like with so many frauds involving forgery, authentication was sought only after large sums of money had been paid out rather than before. Surprisingly, authentication was not made a condition of Stern’s payment for the diaries. The people at Stern had become blinded by the sensational discovery to the point where no one seriously considered that the diaries might be forgeries. Unshaken in the belief that they were authentic, Stern sought the analysis by handwriting experts to silence possible skeptics. The editors had no doubt as to the results of the experts’ analyses, and they were right.

In seeking handwriting analyses, the people at Stern did a strange thing. They cut a single page from one of the diaries, submitting it or copies of it to three experts. The page contained Hitler’s description of Rudolf Hess’s “peace flight” to Scotland on May 10, 1941. Hess, Hitler’s deputy and long-time Nazi associate, is believed to have flown to Scotland on his own initiative to offer a peace proposal to the British government. Hess, a trained pilot, flew to Scotland in a Messerschmitt 110 fighter plane and parachuted onto the estate of the Duke of Hamilton. The two men had first met during the Berlin Olympics in 1936 and had become friends. Hess’s escapade is considered by historians as a futile attempt by a mentally unstable Hess to initiate unilateral negotiations with the British. When Hitler found out what his deputy had done, he was furious.

Now comes a different version of the event from the hand of Hitler himself. In the diary containing events of May 1941 there is an entry explaining Hess’s flight, acknowledging that it was planned with Hitler’s sanction. Should the effort fail, Hitler and his associates would deny any knowledge of Hess’s act, which is, of course, what happened. The editors at Stern decided to test the waters by publishing an account of Hess’s flight using the entry from Hitler’s diary. It was a good move on Stern’s part. If true, the account completely contradicted accepted history and raised intriguing possibilities. If the public and press accepted the story, it augured well for going ahead with publishing the rest of the material. The time had come for the editors at Stern to seek authentication using the Hess page before going any further with the story.

A meeting was held between representatives of the parent publishing firm, Gruner & Jahr, and the editors from Stern. Presiding over the meeting was Gerd Schulte-Hillen, the managing director of Gruner & Jahr. The decision was made to go ahead and publish a major article on the Hess affair in the January 1983 issue, which coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of Hitler’s coming to power. If successful, as nearly everyone at the meeting expected, the article would be followed by a book, which would be serialized in Stern. Wilfried Sorge, assistant to Schulte-Hillen, set out on a long tour visiting various media organizations around the world, offering the Hess story to the highest bidders. The fact that it came from one of several dozen discovered Hitler diaries was still kept a tightly held secret. Sorge’s tour took him to Holland, Belgium, France, Spain, Italy, New York, and Tokyo.

The editors at Stern, however, were not happy with this plan. They felt Gruner & Jahr were going about the story in the wrong way. Stern argued that the diaries in toto were the scoop of the century and that an article followed by a book on Rudolf Hess’s flight to Scotland was the wrong way to introduce the diaries to the public. The story, they argued, should begin with the discovery of the diaries and involve the flight of the Junkers 352 and its fatal crash near Boernersdorf. Unwilling to give up, Henri Nannen and Peter Koch pressed their case with Gruner & Jahr’s managing director, Gerd Schulte-Hillen. The two editors who were once opposed to Heidemann and his “crazy Nazi” story were now on board. It seemed as if everyone had fallen under the spell of Hitler.

To nearly everyone’s surprise, Schulte-Hillen gave in and agreed to quickly switch horses and go with Nannen and Koch’s plan. Sorge was recalled back to Hamburg and told the strategy had changed. Thomas Walde and his assistant, Leo Pesche, saw their manuscript on Hess seriously compromised. Instead of leading the story and being serialized in Stern, it would simply become an accessory publication to the overall story of the discovery and serialization of the diaries.

Now it was Walde and Sorge’s turn to protest. An excited Gerd Heidemann joined them. All three pointed out to Schulte-Hillen that not all of the diaries had been acquired from their alleged East German source. Exposure would surely jeopardize further acquisitions. They had not yet acquired the diaries for 1944 and the D-Day invasion, one of the more important parts of the Hitler diaries. Schulte-Hillen was unswayed by their arguments. The longer they waited the greater the possibility the whole plan would leak, exposing the diaries before Stern was ready to launch its publication. Schulte-Hillen told his group Stern would serialize the diaries beginning with their discovery. Publication was scheduled to begin with the May 8, 1983, issue of Stern and run for eight weeks followed by a summer break. The articles would start up again in the fall of 1984 and run for ten weeks, followed by another break until the following fall, when ten more extracts from the diaries would be published. Twenty-eight serialized articles in all over eighteen months. The word went out from Sorge to all Gruner & Jahr clients (media groups) that the syndication rights were up for sale. Interested parties were welcome to inspect the diaries in April in anticipation of the May publication date.25

Having settled on the plan for publishing the Hitler diaries, Walde went forward with his plan to authenticate the Hess document. If this document passed muster with a select group of experts, Stern would be able to silence any skeptics. Walde asked Heidemann to go with him to the Bundesarchiv, the German Federal Republic Archives, where Walde and Heidemann met with two of the archive’s top officials, Josef Henke and Klaus Oldenhage. They gave Henke and Oldenhage several documents, which they said they would donate to the archive when they were finished with them. Included was a handwritten telegram by Hitler to General Franco of Spain dated January 1, 1940, a copy of a speech dated December 29, 1934, and a letter to Hermann Goering dated October 17, 1940. Two days later they submitted the page removed from the diary containing Hitler’s comments on Rudolf Hess’s “peace mission” to England, but did not tell the Bundesarchiv officials that the page came from one of the alleged Hitler diaries. The Bundesarchiv then forwarded the documents along with five authentic Hitler documents from its own archive for comparison to the West German police headquarters in Rhineland-Pfalz, where police experts analyzed the documents using the known Hitler examples as their standard for comparison.

A week later, on April 13, Walde and Wilfried Sorge visited Dr. Max Frei-Sulzer in Switzerland. Frei-Sulzer was the former head of the forensic laboratory of the Zurich police department. Now retired, he occasionally did consultative work as a freelance handwriting expert. Frei-Sulzer was provided with photocopies of the Hess page and a telegram from Hitler to Miklos Horthy de Nagybanya (Admiral Horthy), Regent of Hungary. For comparison, Frei-Sulzer was also given copies of the five Bundesarchiv documents and several documents from Heidemann’s private collection. Incredibly, the Heidemann documents were all forgeries, meaning that Frei-Sulzer was comparing Kujau forgeries against Kujau forgeries in several instances, which invalidated his analysis.

From Switzerland, Walde and Sorge flew to North Carolina, where they hired forensic document examiner Ordway Hilton as their third handwriting expert. Hilton was retired from the New York City Police Department. He was provided with copies of the same documents given to Frei-Sulzer, compromising his analysis by contaminating the “authentic” group of documents with Kujau forgeries. Thus two of the expert examiners were using forged documents, believing them to be authentic Hitler samples. Further compromising the analysis was the fact that Frei-Sulzer’s specialty was analyzing biological materials, not handwriting, while Hilton could not read German and was unable to understand the material he was examining. Most important, neither man was experienced in analyzing German documents.

Three independent experts were now in place to analyze the handwriting of the supplied documents and report back to Stern. Inexplicably, none of the original documents were subjected to paper or ink analysis. Had those two simple tests been performed, Kujau’s forgery would have been exposed instantly. Not only was this obvious test not performed, but also Walde had contaminated the handwriting analysis by including forged documents from Heidemann’s collection as authentic examples of Hitler’s handwriting for use in the experts’ evaluation.

Seven weeks passed before the final report reached the offices of Stern magazine. Not surprisingly, all three experts certified the Hess document as authentic. Hilton wrote in his report that “there is no evidence within this writing which suggests in any way that this page was prepared by another person in imitation of the writing of Adolf Hitler, and consequently I must conclude that he prepared the document.”26 Frei-Sulzer was more positive in his report, writing, “There can be no doubt that both these documents [the Horthy telegram and the Hess document] were written by Adolf Hitler.”27 The Bundesarchiv was the last to report. Not as emphatic as Frei-Sulzer, its expert nonetheless gave his approval, stating that it was “highly probable” that Hitler wrote the Hess document.28 The fatal flaw in these analyses was in the forged documents from Heidemann’s collection (purchased from Kujau) that the three experts were told were authentic examples of Hitler’s handwriting.

Stern seemed unconcerned with the fact that no forensic analysis had been completed on the paper, ink, and other physical aspects of the diaries, such as the glue, wax seals, and fiber composition of the cord used with the wax seals. Tests on any one of these would have shown that the material dated from after the war. The results of the handwriting analyses were enough for officials at Stern.

Stern had hit a home run. They had three out of three experts certifying the Hess document authentic, satisfying Stern that the diaries were written by Adolf Hitler. Stern was now ready to go ahead with publication of the Hess manuscript. For this, Bantam Books, a subsidiary of Bertelsmann, was the obvious choice. Not only was Bantam part of the parent company, but it was experienced in the American market, something Gruner & Jahr was not. Meeting with Bantam officials, the negotiations went poorly. Louis Wolfe, president at Bantam, wanted guarantees backing up the authenticity of the material, including some form of compensation should the book come under serious challenge. Although Gruner & Jahr and Stern were now convinced the material was authentic, they were reluctant to give any guarantees to Bantam. Bantam was also kept in the dark throughout the talks about the Hitler diaries, which were never mentioned. Besides, Bantam was not particularly interested in serialization of the book, which was what was really at the top of Gruner & Jahr’s agenda. Over the next several months talks took place between the two groups, but in the end Bantam was never given a contract to publish the Hess manuscript. Time soon changed Gruner & Jahr’s original game plan, and the publication of the book wound up on the back shelf.

Since serialization was the ultimate goal of Gruner & Jahr, the officials decided to contact an American company specializing in such rights, International Creative Management (ICM). Wilfried Sorge made sure ICM understood that “only reputable organizations” should be approached: the New York Times, Newsweek magazine, and Time. Negotiations for the American rights under way, the men from Gruner & Jahr and from Stern turned to the media mogul Rupert Murdoch. Murdoch, it turns out, was not only interested in the British and the Commonwealth publishing rights, but the American rights as well. Before making his offer, Murdoch wanted to have his own expert’s opinion on the diaries and their authenticity. He chose one of the best, the noted English historian Hugh Trevor-Roper. Trevor-Roper also just happened to be on the board of directors of the Sunday Times, Murdoch’s most prestigious newspaper.

Bertelsmann’s executive officer, Manfred Fischer, had moved the diaries to the Handelsbank, in Zurich, Switzerland, for safekeeping. The Swiss bank was presumably beyond the reach of German authorities should they attempt to confiscate the Nazi material. Trevor-Roper was greeted by Wilfried Sorge and Jan Hensmann of Gruner & Jahr, and Peter Koch of Stern. Ushered into a special room at the Handelsbank, the historian was taken aback by the volume of materials that were set out for him. On a table were fifty-eight large books purported to be the diaries of Adolf Hitler. Surrounding the diaries was an archive of material, from paintings to letters to artifacts, including a steel helmet claimed to be the führer’s World War I helmet.

Trevor-Roper had set out on his trip skeptical of the claims being made that Hitler had faithfully kept a historical record of his years in power from 1933 to 1945. He had been given a special report prepared by Stern explaining Rudolf Hess’s failed peace mission in 1941 and excerpts from Hitler’s diary showing that Hitler knew of Hess’s plan in advance and approved of it. It was contrary to everything Trevor-Roper knew about the abortive peace initiative and Hitler’s ignorance of it. It was only natural that a historian of Trevor-Roper’s stature would be skeptical of such a historic find as the unknown diaries of the twentieth century’s nemesis.

Although skeptical at first, Trevor-Roper began to shed his doubt. Shown the three separate reports by the handwriting experts retained by Stern and faced with the sheer number of diaries, the historian began to change his mind: “When I entered the back room in the Swiss bank, and turned the pages of those volumes, my doubts gradually dissolved. I am now satisfied that the documents are authentic.” He then added the lines that many other historians took issue with: “the standard accounts of Hitler’s writing habits, of his personality, and even, perhaps, some public events may, in consequence, have to be revised” (emphasis added).29 Trevor-Roper seemed to suggest a kinder, gentler Hitler would emerge from the diaries.

The people at Stern and perhaps more importantly Rupert Murdoch, who hired Trevor-Roper on behalf of the Sunday Times, were delighted. One of the leading historians on the Nazi era and Adolf Hitler had just given his seal of approval to the diaries. It was time to complete the negotiations for syndication rights. The most expensive hoax in publishing history was about to take place. Stern next wanted to get Trevor-Roper’s approval to quote him in announcing their discovery of the diaries. It would be the ultimate proof for the diaries’ authenticity. Stern submitted for the historian’s approval three “quotes” they had made up. Trevor-Roper did not like any of the three, but with pressure from Stern he finally agreed to allow the magazine to quote him as stating that the diaries were the most important historical discovery of the decade and a scoop of Watergate proportions. Given the significance of the diaries had they been authentic, the quote was modest. Watergate paled in comparison. It would later prove embarrassing to the Oxford don.

In fairness to Trevor-Roper, he maintained from the beginning that he could not make a judgment regarding the diaries’ authenticity simply by examining the diaries superficially. He would need sufficient time to sit down and carefully examine typescript translations of the diaries’ content. Only by examining the content of the diaries could he pass judgment on their accuracy and, thus, authenticity. The people at the Sunday Times understood. They told him he would have the time required to thoroughly examine the diaries’ content. Unfortunately, they misled him. Murdoch wanted to move as quickly as possible to head off any competition. He understood Trevor-Roper’s concern, but he needed to make his offer soon or risk losing the syndication rights. Trevor-Roper was asked to call the Sunday Times from Zurich with a “preliminary assessment” of the diaries’ authenticity the same afternoon he began his examination.30 After several hours of pouring through the massive archive of material and listening to Wilfried Sorge tell the story of Hitler’s Operation Seraglio and the crash of the Junkers 352 near Boernersdorf carrying several trunks of documents from the bunker, Trevor-Roper phoned Charles Douglas Home, the editor of the Sunday Times, “I think they are genuine.”31

Rupert Murdoch, a media mogul with interests worldwide, upstaged the people at Stern and Gruner & Jahr by calling their bluff and outmaneuvering them in negotiations for serialization rights. The deal ultimately fell through when the diaries were exposed as forgeries. (Author’s collection)

Back in London, Rupert Murdoch and the people at the Sunday Times were elated. In Zurich, however, Trevor-Roper was already having misgivings. He knew better than to make such an important judgment without carefully examining the diaries’ total content. Any competent historian would have taken time to carefully read the diaries, looking for errors, inconsistencies, and false statements. Once the story broke exposing the diaries as forgeries, Trevor-Roper regained his senses and lamented what he had done. But it was too late. His prestige throughout the world as a firstrate historian meant his endorsement of the diaries’ authenticity would make international headlines. He would forever regret his poor judgment. After the hoax was exposed and criminal proceedings were moving forward against the perpetrators, Trevor-Roper stepped up and apologized for his actions: “Whether misled or not, I blame no one except myself for giving wrong advice to the Times and Sunday Times, whose editors behaved throughout with more understanding than I deserve.”32

Stern had always looked to the Hitler diaries to significantly boost sales and subscriptions to the magazine. The plum would be the syndication rights sold to British and American media companies. At the top of the British list was Rupert Murdoch. Murdoch owned the British Times and Sunday Times, along with a television station in Australia and several other newspapers throughout the Commonwealth, while Time magazine and Newsweek magazine along with the New York Times represented the American interests. The potential market was huge, and Stern stood to make millions on selling the rights to the diaries.

Murdoch was enthusiastic over the potential sales associated with the diaries, and now with Trevor-Roper’s approval he was anxious to negotiate a deal. Newsweek, intent on closing the circulation gap with Time, was also anxious to get in on the money machine, but prudent enough to seek its own expert’s opinion. It hired the University of North Carolina’s esteemed historian Gerhard Weinberg. Born a German Jew, Weinberg fled Nazi Germany with his family at age twelve and became an American citizen. Highly respected as a scholar of the Third Reich for his Guide to Captured German Documents, published in 1952, Weinberg would go on to enhance his credentials as a leading scholar of the Nazi era and Hitler with his monumental history of World War II, titled A World at Arms, published in 1994, and his editing of Hitler’s Second Book, published in 2006.33

A fastidious historian, Weinberg’s initial reaction to the Hitler diaries was skepticism, but curiosity spurred him into wanting to examine the volumes. On learning that Murdoch had already had Trevor-Roper examine the diaries, Newsweek was anxious for Weinberg to see them. They were falling behind and wanted to move quickly. Weinberg flew to Zurich and the Handelsbank, where the diaries were safely stored. The examination did not go well at first. The entries Weinberg examined were too sketchy for him to compare to known events. They predated the entries in the diary of Heinz Linge (Hitler’s valet), and Weinberg was unable to use Linge as a test against which to examine the entries. Hitler’s handwriting was difficult to read and there were no transcripts to work from. When Weinberg came to the diary containing Hitler’s meeting with Britain’s Neville Chamberlain, he found what he was looking for. Hitler had praise for Chamberlain as a negotiator, something Weinberg firmly believed. That coupled with the fact that Hitler signed every one of the diary pages at the bottom convinced Weinberg that the diaries were authentic. No one in their right mind would attempt to forge Hitler’s signature hundreds of times, expecting to get away with fooling the experts. The sheer scale of the forgery added to its plausibility. Newsweek was satisfied. It was ready to negotiate.

Negotiating for Stern and its publisher, Gruner & Jahr, was the publisher’s financial director, Jan Hensmann. Among Murdoch’s entourage was his Sunday Times editor, Charles Douglas-Home. Murdoch did not fool around. Disappointed at not being able to secure the book rights (that was reserved for Bantam Books), Murdock offered Stern $750,000 for the serial rights for Britain and the Commonwealth, and $2.5 million for the American syndication rights—a total offer of $3.25 million. Hensmann was pleased. He told Murdoch he would give him an answer within fortyeight hours, no later than five o’clock Monday afternoon.

At the very moment Murdoch was negotiating for serial rights, the editors of Newsweek were examining the diaries. Later that night following his meeting with Murdoch, Jan Hensmann met with William Broyles, editor-in-chief, and Maynard Parker, managing editor, at Newsweek. After several rejected offers, Hensmann told the two men the price for serialization was $3 million.34 Broyles and Parker said they would have to get back to Hensmann following their return to New York, where they would presumably go over the demand and decide whether or not to pay the asking price.

On Monday, April 11, the Newsweek team phoned Hensmann at Gruner & Jahr and agreed to the $3 million for serialization rights on the condition that the diaries were authentic. Hensmann was flying high. Having promised Murdoch he would call him by five o’clock Monday evening with his answer, Hensmann told Murdoch the deal was off. Newsweek had topped his offer by $500,000 for the American rights. If Murdoch wanted the American rights he would have to raise his offer by that amount to stay in the game. Murdoch exploded! He thought he had a deal when he and Hensmann shook hands on Friday afternoon on Murdoch’s total package of $3.25 million.

Ever the cunning negotiator, Rupert Murdoch got hold of the people at Newsweek and made them an interesting offer, to say the least. Instead of allowing Gruner & Jahr to pit the two organizations against one another, why not join together and make a joint offer, splitting the costs and the diaries. The details could be hammered out later. Newsweek agreed, and the new consortium arrived at Gruner & Jahr’s headquarters, where its chief executive officer, Schulte-Hillen, took over the meeting. Stunned to find the two former competing groups now allied, the Stern and Gruner & Jahr people were crestfallen. They assumed the combined $3.75 million deal was off the table and that the new offer would be substantially lower. To their surprise, the original offer was still acceptable, $3.75 million. The members seated around the table were stunned once again when Schulte-Hillen decided to try and outsmart Rupert Murdoch. “We no longer think that is enough. We want $4.25 million.”35 As if prearranged, Murdoch and his entourage, followed by the Newsweek team, got up from their seats and silently filed out of the room. The deal was dead. All negotiations were over. Schulte-Hillen had overplayed his hand with the master and his bluff cost him dearly. The teams from Gruner & Jahr and Stern were left in stunned silence. Greed had killed the goose along with her golden egg.

The people at Stern now had two major problems, both exceedingly bad. They had lost the two top clients for syndication rights and they had given Newsweek copies of several documents along with copies of the first four articles that Stern planned to run. Newsweek was under no legal obligation to maintain secrecy about the diary discovery or even the contents of the Stern articles. Even if Stern moved up its publication to the earliest possible date, Newsweek could break the story ahead of them by running an article in its next scheduled edition on Tuesday, April 26, 1983. Stern decided to break its normal publication date, scheduled for Thursday, April 28, and move it to Monday, April 25, beating Newsweek by one day and thereby regaining the initiative.

Negotiations had broken down on Friday, April 15, when Murdoch and Newsweek walked out following Schulte-Hillen’s attempt to up the ante after the buyers thought they had a deal. For the next three days Schulte-Hillen had tried to reach Murdoch in an attempt to reopen negotiations. There was no one else big enough to pay the kind of money Murdoch and Newsweek could pay. Despite Schulte-Hillen’s efforts, Murdoch refused to talk to him. On the fourth day, April 19, Murdoch agreed to meet and reopen negotiations—only this time on his terms. He dropped his offer of $750,000 for the British and Commonwealth rights to $400,000, and the American rights from $3 million to $800,000. Schulte-Hillen had no choice but to humbly accept Murdoch’s offer. He had cost Gruner & Jahr and Stern $2.5 million by his arrogant attempt to shake down Murdoch.

Having settled with Murdoch on the mogul’s terms, Gruner & Jahr would announce the discovery of the diaries on Friday, April 22, followed by publication of their first article on Monday, April 25. Murdoch would publish Trevor-Roper’s article authenticating the diaries in the Saturday edition of the Times, followed by the first of several articles on the diaries in the Sunday Times of April 24. Trevor-Roper would write the lead story. He worked all day Thursday, April 21, on his article and handed it in to the Times on Friday, the 22nd. That evening he and his wife joined a group of Cambridge University colleagues in attending the Royal Opera at Covent Garden in London.36 It would prove to be a disturbing night for the renowned historian. The more he thought about the diaries and the circumstances surrounding their discovery and “authentication,” the more troubled he became. By the time he returned home it was too late to withdraw his article. The presses were already running.

All the while that Trevor-Roper was skillfully weaving his qualified endorsement of the diaries, Dr. Arnold Rentz, a forensic chemist, was working overtime analyzing three sheets of blank paper removed from two of the diaries and handed to him by Dr. Josef Henke of the Bundesarchiv along with a telegram allegedly sent by Hitler to the Italian dictator Mussolini. At long last someone was doing forensic analyses on the diaries other than handwriting and content analysis. Rentz determined that the pages did not contain the special whitening substance used in the manufacture of paper after World War II, but that the telegram did contain a whitening substance and was created post-1945, and was therefore a forgery. The editors at Stern were troubled by the results of Rentz’s tests. Peter Koch, the senior editor, was afraid that any question involving the authenticity of any of the documents in Heidemann’s possession equally cast doubt on the diaries’ authenticity. Stern was hours away from holding a press conference announcing the discovery of the Hitler diaries and their publication. Koch raised his concerns with Schulte-Hillen, asking him to get Heidemann to reveal the source of the diaries and confirm their origin. Heidemann refused, standing by his original claim that revealing his source would jeopardize the lives of people in East Germany who were involved in smuggling the documents to him. In his concern, Heidemann may well have believed his position. Schulte-Hillen was satisfied that Heidemann was telling the truth and that the diaries were authentic. Besides, there was the endorsement of the genuineness of the diaries by one of the leading historians of the Nazi era, Trevor-Roper. Unfortunately, no one at Stern or Gruner & Jahr was aware that Trevor-Roper was having second thoughts about his endorsement.