Success is a lousy teacher.

It seduces smart people into thinking they can’t lose.

—BILL GATES

By 1999, Media Arts claimed Thomas Kinkade was the most collected living artist in the world. Two hundred forty-eight galleries sold his work across the country. His personally highlighted canvas transfers sold for $34,000 or more, and Media Arts posted $126 million in revenues and $84 million in profits for the fiscal year. Later in that year, 60 Minutes aired a long piece in which Morley Safer said Thomas Kinkade was to art what Henry Ford was to automobiles. The world was taking note.

The modern art world was scratching its head. Whoever heard of a painter’s atelier the size of a 100,000-square-foot warehouse? The avalanche of imagery coming out of Charcot Avenue was considered commercial kitsch, but no one could deny its pervasive appeal. And Thom was not apologetic about his status as a populist artist. He didn’t want to be part of the rarified art world, creating the kind of art that was only for the elite few to enjoy. He didn’t mind that his art was shipping out by the truckloads, because it meant he owned the heart of the people. As the art world looked on the phenomenon of the extensive replication of Thom’s art with skepticism and mistrust, Thom’s success almost seemed to be mocking its veneration of the concept of the original art object. By producing the canvas transfers and adding dollops of paint, thereby making a copy unique and original again, it almost became a postmodern exercise in the semiotics of art.

While the art world scorned the notion that art should be used to quell people’s anxieties, Thom was proud that his paintings provided inspiration and reassurance. He said, “High culture is paranoid about sentiment, but human beings are intensely sentimental. And if art doesn’t speak language that’s accessible to people, it relegates itself to obscurity.” He tapped deeply into that sentimentality, and there was just no arguing with his success. Thom resigned himself to his outsider status in the world of fine art, and referred to himself and his work as the “Trojan horse in the enemy camp.”

To me he would say, “They didn’t appreciate Norman Rockwell when he was alive. Even Rockwell didn’t think his art was worth anything. He gave paintings away to his neighbors and the milkman. And now they’re worth a million dollars. Popular sentiment prevailed. I think it will be the same with me. I just don’t know if I will live to see it myself.”

At least Thom didn’t have to wait for the monetary rewards of his work. The signature galleries were selling the multitiered editions like crazy, from his images in basic paper prints for a few hundred dollars, to the pricier canvas lithographs in multiple editions, with names like “standard numbered,” “Renaissance edition,” and “prestige collection.” Collectors who paid $2,500 for a canvas transfer painting were content because the added special highlighting meant that, even if the next-door neighbor had the same image hanging on their wall, they were still different and unique works.

When the shipping bay at Charcot stacked the ready-to-ship paintings twenty feet high in the air, the sheer volume of sales posed one interesting dilemma. Thom could not physically sign the artworks, numbering in the hundreds, even thousands, that were leaving the warehouse every day. A machine was devised that would replicate his signature on every work of art, and in order to comply with the industry standards of authentication and originality, a little bit of Thom’s blood was mixed into the ink, which would make his signatures verifiable as authentic by providing Thom’s actual DNA. It only took a drop of blood to mix enough paint for a thousand canvas transfer paintings, but it almost made him into a martyr, a Christ-like figure. Here he was giving his blood for his art. And the public ate it up.

![]()

When Ken was voted out of the company, he was still its largest shareholder. After he returned from Hong Kong, he hired a lawyer whose first communication put Media Arts on notice that they had better be careful; that even though Ken accepted the company’s decision, he still had compensation rights outside of his former salary. Ken not only had the power to potentially wreak havoc if he were ever to sell a large share of his stock as a now disinterested shareholder, but he also had the ability to sue the company for alleged mismanagement. Thom also knew that Ken knew his personal secrets. Things that might not be perceived as flattering: the many late nights spent drinking, and drinking too much in general. Ken was not the kind of person who would ever exploit that kind of advantage, but he also wasn’t going to let the Kirby sales team run the company he had founded into the ground. In the first period after the separation, nerves of those on both sides of the fence were on edge in a standoff.

There was a bond between Thom and Ken that couldn’t be denied, one that reached back to their common dream in founding the company. But something had gone wrong along the way. They had become subtle competitors rather than allies. Of course they owned a business together, but it seemed to have become about the chicken or the egg. Who was there first? Who was the germinator? Of course everything started with Thom, but Ken’s original investment perhaps gave him a proprietary sense of his role in the company. This rivalry was slowly shifting Thom away from the person who was actually his true and loyal friend. Their friendship represented the soul of the company; breaking that unspoken bond could disturb the balance of the spirit and heart of the company. With Ken gone, Rick was bound to gain more ground, and I wasn’t sure if Rick was the same friend to Thom as Ken was. It was just who they both were. I felt they belonged together, and couldn’t imagine how they would fare apart.

Ken confided in me in those days: how unappreciated he felt and how insulting, even devastating, it was to be scuttled from one’s own company. But Ken was a loyal person. He felt that Thom truly was his friend, his best buddy for a lifetime. While he expressed that he was really hurt, he couldn’t and wouldn’t do any harm to anyone, or betray the love and friendship he had with Thom. So Ken accepted his fate, and he became determined to be successful as his own living proof of the adage that there is no better revenge than success. Silicon Valley and the Internet were booming at the time. Apple and Google were emerging and AOL was the hottest stock around. And Ken was drawn to their explosive growth potential.

We had lunch a week after his leaving the company, and he told me he was getting into the Internet business. It was 1999, and Silicon Valley was exploding; he wanted in on the action.

“You want in, Eric? Let’s go,” he said.

I had been thinking about my own future at the company. I was deeply loyal to Ken, and I was inclined to follow him. And despite the failure of diversification, I knew he had become the fall guy. Everything sticks to the CEO. It might have been his passion, but everyone at the company had also been on board with diversification. The blame just stuck to Ken in the end.

He told me that when I was ready, he wanted me to come and help him. He had been talking to some people and wanted to start a company called Familyroom.com that could bring like-minded faith-based families together in a safe place.

“That sounds like a good idea,” I said.

There were many reasons why Ken’s offer sounded good to me. It wasn’t just that Ken had left; it was that with Ken’s departure it seemed as if the heart and soul of the company were gone. For all his ambitions and visions of expansion, ultimately Ken cared deeply about the company he had cofounded with Thom, and he shared their mutual vision of building the best art publishing business they could. And there was a spiritual dimension that Ken and Thom shared: a sense of destiny and spiritual mission. Ken also wanted to do good. I knew that with Ken being gone, the group of former Kirby salesmen who now held high positions in the company would shift its focus exclusively to sales, without the vision required to shape a market.

Granted, sales were going through the roof, and profits continued to rise. Rick Barnett had proven himself for a long time. Now he was opening more signature galleries, running Thomas Kinkade University, and bringing in numerous trained gallery owners. Ken had always been in the way of Rick’s making the real decisions. Rick was never CEO; he couldn’t tell anyone what to do and he didn’t try. He gave his opinions, went back to Monterey, and exerted his influence behind the scenes with Thom, in private. With Ken gone, Rick was empowered. According to other executives still at the company, the first thing Rick did after Ken’s dismissal was to negotiate a deal for himself by which he would receive a commission on every piece of art sold by the company.

But it wasn’t Rick Barnett that was the problem; it was the aggregate trend. In the void left by Ken’s departure, Greg Burgess and Brad Walsh rose to power. Greg and Brad were bold and brash and had waltzed in, acting like they owned the place. And besides my nearly coming to blows with Brad Walsh, tensions constantly ran high between the old guard and the new. Dan Byrne, Kevin Sacher, and the other original members of the executive team had been at the company for many years, and although the volume of sales kept increasing, we all felt there was no more soul in it.

Two days after Ken and I returned from Hong Kong, I received a call from Thom at my Charcot office.

“Eric, since Ken is gone, you need to know that I’m going to be doing some housecleaning at the company. We’re getting rid of anything that was part of the Ken era.”

He told me I needed to know he had decided to install Greg Burgess as chairman of the board, and CEO and president of the company. I was stunned.

“Okay,” I said hesitantly.

Thom said he knew I was obviously a big part of Ken’s time at the company and normally I would be a candidate for this housecleaning he was planning to do.

“But I’m going to protect you,” he said.

“I appreciate that, Thom.”

“Just go and pledge your loyalty to Greg. He knows that you were close to Ken, and needs to know that you fully support him now.”

I was torn. I had established the single biggest art-licensing program in the world. Thom was my good friend, as was Ken, and I didn’t want to let either of them down. I was earning a lot of money at Media Arts, and I was expecting to earn a lot more in the coming years as my licensing contracts matured and I added even more licensees. I didn’t know what I should do. Take Ken’s offer? Pledge allegiance to a man I didn’t respect? Give up my very lucrative position at the company?

I then understood that my blind faith in Ken had been just that: blind. I had been like a racehorse at Churchill Downs with the blinders on, focusing on the race in front of me, unable to see the developments on the sidelines. By placing all my trust and energy in Ken, I had sidelined myself along with him. I never entertained the thought that Thom, Nanette, and the board were right on some level, so I was stunned. I was naïve to the fact that the board of directors at Media Arts could do something like this, ousting Ken, an actual cofounder, from his own company. I hadn’t seen it coming; no one had ever indicated this might happen. During all of my years in business, I’d never seen anything like it. Ken’s world had collapsed around him. He had been toppled from his perch, and everything he’d built had been taken from him. My head was reeling. Where did I fit in?

Even though I understood what was happening and why, I wasn’t sure I could go through with Thom’s plan. I agreed to take the meeting with Greg with a strong sense of foreboding. Until that time Greg and I had kept up a friendly and cordial relationship. He was a sharp sales guy. He would get on planes and establish more galleries so we could increase our sales and see our stock value rise. Hell, these new galleries were even selling my licensed products now. Suddenly, with Greg’s support, there were a thousand new points of sale for my calendars and ornaments.

I appreciated Greg’s sales ability, but I didn’t think he was a CEO. He had never run a company of this size before; in fact, to my knowledge he had no experience as a CEO whatsoever, let alone CEO of the largest art company in the world. The anomaly of having Pastor Mike Kiley as a vice chairman was bad enough, and now the head sales executive was going to be our CEO? Like the captain of a ship, the position of CEO requires extensive management and leadership skills. It requires steering the ship and running the crew at the same time. Greg was like a navigator with his compass pointed north, but without a plan for how the company would ever travel in that direction. It made no sense to me. The company was at its peak, firing on all cylinders for the first time. I understood that Thom and the board looked at Ken as someone who would threaten this new prosperity and stability, but putting a sales guy in as chief executive officer, let alone chairman of the board, was counterintuitive. It felt like one step forward and two steps back.

I decided to go and see for myself what was happening and hear what Greg had to say. So I set a time to meet with him. I went into the new CEO’s office, two weeks after returning from Hong Kong.

Greg sat behind the desk in what was formerly Ken’s opulent office. Greg’s family photographs were arranged behind him. It all felt surreal to me. We made small talk and shared uneasy laughs about the unexpected turn of events engineered by the board of directors. Greg asked me how Ken was doing.

“Not well, as you can imagine,” I said.

Greg then ran through his speech about the new world order, telling me the Ken era was now firmly in the past and a new team was being installed to take the company to new heights. Then he got to the point. He told me that although my affiliation with Ken made them all concerned, the company still wanted me to head up licensing and strategic relationships.

All this talk about a new day, new people, a new plan, and a new company made me uneasy. I understood that I was valuable, and that the company could use me. But did I really want to do this? Thoughts of Brad Walsh threatening me while Greg stood passively by flashed through my mind. I asked Greg what his plan for the company was.

Greg looked at me, then he seemed to fumble for words.

He simply said that Brad Walsh was now going to be senior vice president of sales.

I looked at him and asked if that was all.

He paused and added that he planned to make sales the focus of the company.

It seemed clear to me that he didn’t really have a plan at all. His new plan was the old plan; his new job was the old job. The sales guy was not a CEO, and it hit me that I could never and would never pledge my loyalty to Greg; that I could never report to a man whom I felt didn’t know what it took to run a company like ours. That this situation was a disaster waiting to happen. He had a limited vision for a company as large and complex as the multimillion-dollar giant Media Arts was. He knew sales—and sitting across from him that day, I sensed it was the only thing he knew.

I did the math in my head: six Kirby guys running the show and a pastor for vice chairman. It seemed like a terrible joke; a dangerous game, a theater of the absurd. I wondered what my wife would say. I thought of the cushy salary I was drawing. I thought of Ken alone at home, after all we had done together. I saw myself sitting in executive meetings and having to answer to Greg Burgess, a man for whom I had little respect. And it was too much for me to accept. At least I respected myself. Perhaps it was impetuous; I know I didn’t think it through. Would I do it again? Maybe. But in that moment I was just furious. And I knew what I had to say.

“Greg, this isn’t going to work for me. If you need to fire me, then fire me. I remain loyal to Ken; I cannot and will not report to you. Good luck.”

I rose and walked out of the room, leaving a stunned Greg behind.

When I told my wife that night, she was happy to hear it. She knew how unhappy I had been since the Kirby crew came on board.

“At least you’re not going to have to be around those phonies anymore,” she said.

“What about the paycheck?” I asked her.

“You’re the one with the licensing talent. They needed you more than you needed them. You’ll make a living like you always have. But you’ll do it on your terms next time,” she said.

She was always so practical. And she was always right.

Ken and I got together some evenings later and talked about how everything at the company had become a circus. While Ken was distraught over being ejected from the company, he was also worried about Thom. I remember how that struck me as strange. Despite his own setbacks, Ken was still thinking of his friend. But that was the nature of their relationship; they were like competing siblings who ultimately always remained bonded. Ken felt that the board, and the heavy influences around Thom, had made him oust his own friend and partner. He felt Thom had been duped into a bill of goods introduced by Rick and the other board members. He knew Thom was not a leader, not a decisive person. He tended to avoid hard decisions and let others make them for him. And Ken also worried about Thom’s increasing alcohol issues and how they affected his judgment and made him vulnerable to manipulation.

It impressed me that Ken would think of Thom over himself in that moment. It spoke volumes about him, and their relationship. Even though he had been spurned, Ken had an abiding love for Thom that was moving to witness. Despite his own woes, most of all he didn’t want the Kirby crew to end up hurting Thom.

We sat in silence for a long moment, letting it all sink in, staring into our cocktails. Then Ken suddenly began to smirk. His smile was strange for such a somber moment, but he just couldn’t stop. It was infectious. I was smiling, too, by now. I asked him what he was smirking about.

Ken seemed to have realized that since he was the largest shareholder yet had no more executive or director obligations to the company, he still had a voice, but his responsibilities were significantly diminished. As the controlling shareholder, he had protected rights, and in a sense, he would be more powerful than ever. I had to laugh, too. I knew Ken wouldn’t abuse his power by any means. But he at least had the ability to keep a watchful eye and prevent people like Brad Walsh and Greg Burgess from destroying the company.

I thought Ken was right. As the chairman of the board, the president, and the CEO of Media Arts, he was bound by very strict SEC rules and fiduciary responsibilities to the company. A senior executive must act in the company’s best interests, first and foremost. But a shareholder is free of the restrictions of financial obligations to the company, and is instead guaranteed, under the law, a certain protection of their investment. As the largest shareholder, Ken still had implied influence, yet he was suddenly free for the first time in many years, from restrictions placed on him as a corporate executive at the company.

Days after he was removed, Ken’s lawyers called Greg Burgess, and a letter to the board of directors was delivered. They were informed that Ken would, from now on, be scrutinizing every significant action the company planned to take; and that, if he was not in agreement with the company’s decisions and policies, he would not hesitate to take action. Thom and Nanette thought they had finally removed Ken from the company, yet now as the largest shareholder, but no longer an executive, he was in a sense more involved than ever. Ken had won this round in the end.

Ken wasn’t trying to get a little payback for his ousting. He was genuinely concerned for his investment. Not only had he been ousted from the company he cofounded, the company he had based his whole life on, but by his own estimation, a man of questionable competence had been put at the helm. His newfound influence was a salve to the wound. From now on, he had the ability to influence the executive management team at Media Arts if they made any misstep that he felt put his investment at risk. And from that point on, as it turned out, Ken made more decisions and more money from the company than he ever had in the past.

I took my severance package from the company, vacated my office at Charcot Avenue, and joined Ken in his new Internet adventure.

It was a time of big changes at the company. By the end of that year, Dan Byrne, who had been named president after Ken was removed, left the company. James Lambert, the vice president of publishing, as well as the vice president of marketing, Kevin Sacher, also left. Bud Peterson resigned. Paul Barboza, senior vice president of sales, resigned. Jay Landrum, general counsel for Media Arts, made it clear that he would not support Greg Burgess in his new role, and refused to report to him. The board was firm in its decision, and Jay also resigned. All of the original senior executives, with only a couple of exceptions, were gone by the end of 1999.

![]()

Silicon Valley was bustling with wealth and innovation. When I joined Ken for his first venture, Familyroom.com, he had hired several Internet consultants to help him build the business. Internet consultants were proliferating in Silicon Valley, eager to take the money of the aggressive get-rich-quick start-ups riding the Internet wave. Unfortunately, some of these consultants were not much more than scammers taking advantage of gullible investors. Ken was eager to forge ahead at the fastest possible speed with his Internet concepts, and was ready, able, and willing to write the checks needed to finance the venture. The cadre of consultants always had their hands out for another check.

Despite the heavy infusions of cash, Familyroom.com was a failure.

Ken started another company, OnVantage Inc., a desktop portal that a company could use to create a company hub and develop its brand. That, too, didn’t work.

I watched Ken hire many people over the next two years who were more than willing to take the millions of dollars he was willing to invest; by some accounts, between two and three million in all. I did everything I could to support him. I worked for him for free for a year, trying my best to assist him in his Internet ventures. I was paid for another year, working with him toward launching his web concepts. But to no avail. The dream to become an Internet billionaire became more and more elusive. Ken’s initial enthusiasm slowly gave way to discouragement.

In 2001 Ken and I were on a business trip in New York City, having lunch at the famous Café des Artistes on West 67 Street in upper Manhattan. We sat, surrounded by the stunning murals of forest scenes and wood nymphs by Howard Chandler Christy, talking about the state of things. He was particularly down; he looked defeated and demoralized.

Ken seemed depressed about the bad turn of events with his plans in the Internet business. His hopes of showing Thom he could be successful without him were dashed. I tried to cheer him up as best I could.

“Forget about the Internet thing. It’s only money. But you still have lots of resources, you still have me, and you’ve got lots of talent. Let’s get back into the licensing business. My phone rings off the hook all the time, and I tell them that the reason I haven’t been licensing is because I’ve been working with you. But we can get back into the game together.”

He looked moved, and asked if I would really do that. I assured him I would. That day, Ken seemed to rally again.

I didn’t tell Ken that Thom had been calling, begging me to return to the company to head its licensing. I had spoken to Thom on a number of occasions over the past several months, and he reminded me how well we worked together. He said there was still so much we could do with his brand. I always thanked him and said I was pretty settled right where I was.

“But we created so many licenses together! How many was it?”

“Over seventy-five.”

“Let’s make it a hundred. Let’s make it two hundred. I have so many ideas!”

But I was loyal to Ken, and my family was back in Santa Barbara. I told Thom I liked working at home. Thom said I could commute the way I had before. I told him I would think about it.

But I didn’t want to go back to what I had walked away from. I knew that what made me leave when I did was certainly not likely to have become any better. The day I left the company, I had told my wife to sell all our stock. I didn’t have any faith that the Kirby crew could sustain this juggernaut of a company in the long run. But I did see the potential to continue to be effective with the licensing side of the business. I just knew it had to be on my own terms. When I pledged that I would never answer to Greg Burgess, I had meant it.

I finally floated it out to Ken that I had been thinking about getting back into the licensing business and thought of representing Thomas Kinkade again, this time as an independent contractor. And I told him I wanted us to do it together. Ken was torn. He didn’t know if he had really recovered all his pride, or gotten over the hurt of Thom ousting him from their mutual labor of love. Wouldn’t it be awkward to return after the shame of being removed? Ken didn’t know I had been working hard behind the scenes to convince Thom it made sense to bring Ken back along with me. But ultimately he agreed, and we formed Creative Brands Group, a company specializing in the management and licensing of brands. As I knew them both well, I became somewhat of an ambassador between these two men, who clearly still had a deep emotional and spiritual connection to one another. When Ken said yes, I privately started negotiating our return with Thom.

I told Thom I had been working with Ken for two years now, and I thought he was a good person, and I just wouldn’t feel right leaving him out of it. So I told Thom that if he wanted me to work with the company again, I would have to bring Ken along, since we were partners now.

Thom was hesitant. I reassured him that he knew me and could trust me; that I would be his guy and that we would do it the way we always did: together. Ken would certainly be involved, but I would be managing his licensing business. Finally, Thom said that if Nanette okayed it, then he was fine with it.

Days later, I met with Nanette in the kitchen of her house and told her all the same things I had told Thom. I half expected her to say “absolutely not” the moment I walked in. I knew she still blamed Ken for the company losing so much money. But she listened thoughtfully and finally agreed. I was exceedingly happy that I didn’t have to talk her into it. The thing about Nanette was that she was always protective of Thom. She really cared about his welfare, his career, and how he was treated by others. She never spoke out against him, never let any seams show if there was trouble at home. Nanette was always that perfect, poised, supportive wife in her husband’s corner, and I respected her for her dedication and her dignity. A few weeks later, we signed a deal stating we would represent Media Arts exclusively for all their licensed products.

![]()

Thom was a down-to-earth man driven by his ebullient enthusiasm for life and an earnest desire to do good for others. Whenever the mention of his success came up, he credited his faith in God, and his desire to let God use him as a vehicle for good. He didn’t want to build himself up, and he didn’t want to be elitist. He preferred the corner dive bar, where he could talk to the regular guy sitting on the stool next to him, over any expensive dinner at the Four Seasons. He genuinely loved the regular people, the fans, the devoted collectors, the supporters. Despite his millions, he was always that country boy at heart. And his connection to Ken ran as deep as his roots in Placerville. After all, they had done it together, back in Thom’s garage, printing and packing, and selling their wares out of Thom’s pickup truck. Nothing runs deeper than a shared dream.

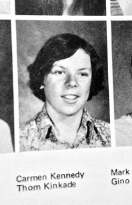

Thomas Kinkade at age 16 in “The Riffle” yearbook of El Dorado High School, Placerville, CA, 1974. Courtesy of Gold Country Girls

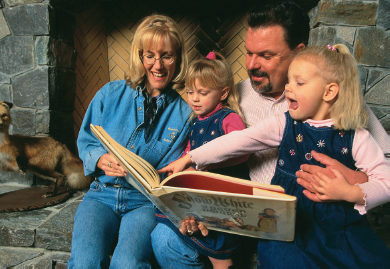

Thomas Kinkade with Nanette and their daughters. Monte Sereno, CA, 1995. Thomas Kinkade and Family © John Storey/Corbis

Kinkade in his studio with daughter, Winsor, 1995. © Getty Images

Media Arts Group headquarters at Ten Almaden Boulevard, San Jose, CA, 1995. Courtesy of G. Eric Kuskey, 2014

Bonus checks at Media Arts on Charcot Avenue, with Thomas Kinkade, Bud Peterson, and Ken Raasch, San Jose, CA, 1997. Courtesy of Bud Peterson

Media Arts Group goes public, December 7, 1998. From left: Jay Landrum, Brenda, Greg Nash, Richard Grasso, Ken Raasch, Bud Peterson, William R. Johnston. Courtesy of New York Stock Exchange Archives, NYSE Euronext

Steve Kincaid and Thomas Kinkade in High Point, NC, 1998. Courtesy of G. Eric Kuskey

Thomas Kinkade, Rick Barnett, and Terry Sheppard at a book signing event, 2000. Courtesy of Terry Sheppard

One of the many licensed products of Thomas Kinkade. Courtesy of G. Eric Kuskey

A gambling trip to South Lake Tahoe, CA, 2002. From left: Jay Landrum, Ken Raasch, Eric Kuskey. Courtesy of G. Eric Kuskey

A night on the town with the boys. From left: Jay Landrum, Thomas Kinkade, Dan Byrne, Kevin Sacher; San Jose, CA, 2002. Courtesy of G. Eric Kuskey

Thomas Kinkade painting the Christmas tree at Rockefeller Center, New York City, 2007. Copyright © Bennett Raglin, Wire Image, Thomas Kinkade Paints the 2007 Christmas Tree Rockefeller Center, Getty Images 2007

The Pied Piper of Hamelin by Maxfield Parrish (1909) was commissioned by the Palace Hotel of San Francisco for $6,000. It has been hanging in the art deco bar of the Palace Hotel in San Francisco since 1909, and garnered a recent estimated value of $3 to $5 million. Courtesy of the Palace Hotel of San Francisco

Thomas Kinkade’s mug shot after his DUI. Carmel-by-the-Sea, CA, 2010. Courtesy of Salinas County Superior Court

Kinkade at the 137th Kentucky Derby, 2011. Copyright © Joey Foley, Film Magic, 137th Kentucky Derby Arrivals, Getty Images 2011

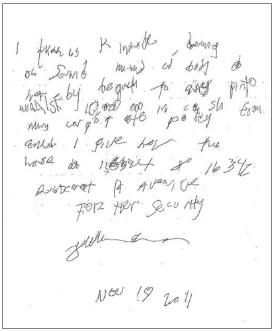

“I, Thomas Kinkade, being of sound mind and body do hereby bequeath to Amy Pinto Walsh $10,000,000 in cash from my corporate policy and I give her the house at 16324 and 16342 Ridgecrest Avenue for her security.”

Thomas Kinkade handwritten will (#1), 2012. Courtesy of Santa Clara County Superior Court

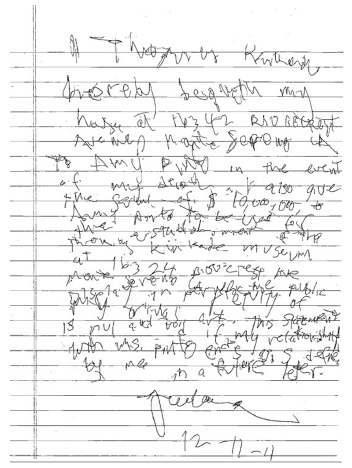

“I, Thomas Kinkade, hereby bequeath my house at 16324 Ridgecrest Avenue, Monte Sereno, CA to Amy Pinto in the event of my death. I also give the sum of $10,000,000 to Amy Pinto to be used for the establishment of the Thomas Kinkade Museum at 16324 Ridgecrest Avenue, Monte Sereno, CA, for the public display in perpetuity of original art. This statement is null and void if my relationship with Ms. Pinto ends as it is defined by me in a future letter.”

Thomas Kinkade handwritten will (#2), 2012. Courtesy of Santa Clara County Superior Court

Money changes things and people can lose their way, but Thom and Ken were still the same two men inside. They both came from broken homes and a single mother. They knew these things about each other, and it seemed to make their connection stronger. It always seemed to me that Ken would have done anything for Thom and, misguided or not, he always did his best for Thom.

Thom’s connection with Rick didn’t seem to me to be as personal as it was with Ken. Rick was good at establishing confidence; perhaps that was what made him so successful in sales. He could establish trust, but he hadn’t risked anything with Thom the way Ken had. He had simply delivered. He had taken Thom and sold him to the world, just like he had promised on the very first day they met at the Carmel-by-the-Sea art fair. Rick wasn’t sentimental; he was an enigma, carefully keeping to himself, playing things close to the vest.

I found myself caught in the triangle among the three friends. It had all the makings of a romance, without the actual love affair. I observed the ebb and flow of shifting sands of allegiance that continually vacillated among Thom, Ken, and Rick. Rick made Thom feel good, but beneath his smooth ways he himself was elusive, unreachable. Ken was the devoted friend who was always there. No matter what Thom dealt out to Ken, Ken would remain true. Thom went to Rick for business matters, but he went to Ken for matters of life.

Ken was Thom’s conscience, his reasonable older brother, the one who could talk him down from a ledge or stop him from doing something crazy when he’d had too much to drink. Once Ken was missing from Thom’s life, stories in the vein of “you won’t believe what Thom did now” began to hit the rumor mill.

There was the story that made its way to me of Thom’s trip to Las Vegas sometime in the year 2000. He had gone for a weekend of cards and roulette with Nanette and his mother in tow. His mother was still living in one of the houses on his property. Thom had certainly taken care of her after their early struggles together.

They went to the Mirage Hotel one night to catch the Siegfried and Roy show, with a nice table near the stage where they could see the tigers up close. For his mother it was a special treat to go to a Vegas show. Such luxuries were a dream when she lived in that trailer home with her kids, working three jobs to get by.

From what I heard, Thom had been drinking heavily in the evening and was already past the point where he had his faculties about him. A couple at an adjacent table had already gotten up and asked the waitress to relocate them because of Thom’s boisterous antics.

When Siegfried and Roy appeared out of the dry-ice fog on stage, the tigers were roaring and pawing from the platforms, music playing as the light show danced over them. The duo strode forward to the cheering and applause of the crowd, their arms outstretched. As they neared the edge of the stage, they came close to Thom’s table. Thom caught sight of Roy, dressed in leotards and tights, wearing a protective codpiece. At that moment, Thom leapt up from his chair and pointed at him.

“Codpiece! Codpiece!” he yelled, laughing hysterically.

Thom’s mother and Nanette reached out to him, looking embarrassed, grabbing his arm desperately, both of them pulling on him, trying to get him to sit down and be quiet.

“Codpiece!” Thom yelled again, laughing.

Nanette and his mother insisted that he sit down. Thom briefly focused his eyes on his mother and saw the look of concern in her face. Finally he came to his senses and sat back down in his chair, still chuckling to himself.

Thom voraciously took in all of life, consuming the world as though it was going out of style, which included his increasing consumption of alcohol. Ken had tried to hide Thom’s addictive nature from me in the beginning. I think he didn’t want me to think less of Thom when I first worked for the company. He wanted me to like Thom and be comfortable being friends with him. I think Ken wanted it for Thom’s sake and for the sake of our business.

By the time Ken and I returned to work with Media Arts, Nanette seemed to have given up trying to change Thom. She kept herself separate from the inevitable late-night drinking tours that went on when he left the house. Ken covered for Thom in our business, and went out of his way to avoid scheduling meetings after a certain hour in the evening. Thom would sometimes become visibly uncomfortable at signature gallery events at which there were only a few people present, or those that were held at someone’s home, perhaps because it meant he couldn’t drink. He would become visibly agitated and do everything he could to end the evening early. It was the unspoken secret that wasn’t a secret; it simply wasn’t discussed. When the drinking became impossible for me to overlook, seeing Thom drunk and drooling at the end of a night, Ken said, “I don’t know what’s wrong with him. He’s just a man of great appetite.”

There were more incidents such as this in the two years when I wasn’t part of the company and not directly in Thom’s life. I heard about them from James Lambert, who heard it through Terry Sheppard. Terry’s job was to chronicle Thom’s life through photography and film, and hang out with him late into the night. Terry was actually a talented filmmaker and a willing accomplice to whatever whim Thom was pursuing at the moment. He followed Thom around with a camera and made video after video, documenting every part of his life. It was meant to preserve Thom’s legacy, creating a video record of the events of his life and the many things he accomplished.

Inevitably the days of shooting would turn into nights of carousing and drinking, and Terry would go off the clock, turn his camera off, and, along with other members of the posse, simply join Thom as a drinking buddy. Thom had promised Terry a place in the company for his loyalty and devotion, but Nanette felt less favorably about Terry as an enabler of Thom’s late-night ventures. Terry became a witness to the goings-on, and one felt that he had plenty of stories to tell.

It was Terry who was present when Thom took a trip to Southern California for a meeting with Roy Disney. He was also making an appearance on the Hour of Power, a religious television show shot at the Crystal Cathedral in Garden Grove with Pastor Robert Schuller. After his appearance on the television broadcast, Thom and Terry hit the town and went drinking into the night. According to Terry, they teetered back to the Disneyland Hotel early in the morning, Thom completely inebriated. As they approached the hotel, Thom caught sight of a large statue of Winnie-the-Pooh. Thom zigzagged to the statue, zipped down his pants, and urinated on the statue.

“This one’s for you, Walt!” he laughed as he relieved himself on the unsuspecting Disney figure.

Terry was also present when Thom was visiting Las Vegas and the opulent European-style Bellagio Hotel, where some of his artwork was hanging in the hotel’s restaurant galleries. As they were riding the elevator up to their suites after a late night, Thom drunkenly unzipped his pants and urinated into the corner of the elevator.

There is another incident I heard about through the grapevine. Thom had gotten so drunk one night while out with John Dandois, an executive at Media Arts, his wife, Mary Louise, and others from the company that he fell down and couldn’t get up again. Mary Louise reached out to help him off the floor, but Thom was so inebriated and ornery that he flipped her the finger, repeatedly saying, “F—you.”

Hearing these stories wasn’t a surprise, but always left me with a sense of unease and worry for Thom. The excessive drinking was a part of his life we all wished wasn’t happening. And there was always that apprehension, what will happen this time? Will he hurt himself this time? Will someone find out? Keeping the two sides of Thom straight was a challenge in life and in one’s mind.

I felt it was high time to get back into Thom’s life, and for Ken to be back and involved with Thom. At least we might be a positive influence. It sounded to me as if the soul of the company had left with Ken, and Thom had become a little lost in the process.

![]()

Morgan Hill is an upscale bedroom community to Silicon Valley, sprawling over hills and ridges carpeted with grasses and wildflowers, with lush vegetation in its creeks and valley bottoms. Buttressed by the Santa Cruz Mountains and the Diablo Range, Morgan Hill’s natural beauty and small-town charm made it a natural location for Thomas Kinkade’s new company headquarters.

Several changes had taken place during Ken’s and my two-year absence from the company. Sales had continued to increase to such an extent that the 100,000-square-foot warehouse at Charcot Avenue was no longer sufficient to handle the volume of output and demand. A business park location in Morgan Hill was chosen for its proximity to San Jose and Los Gatos, and its convenient shipping position on the 101 South Valley Freeway.

Inside the Madrone Business Park complex the company built a campus that housed a 61,000-square-foot headquarters, an adjacent 155,000-square-foot production facility, and another 56,000-square-foot production and distribution building. A 127,000-square-foot distribution facility was located nearby, directly on Madrone Parkway. Nearly half a million square feet were devoted to servicing the business of one painter.

Canvases were pumping out by the truckload. The focus on art sales and the push for profit had built the house. But in the art market, in which value is built on scarcity and the exclusivity of limited editions, I wondered if that focus on sales, in such prolific volume, could continue in the long run.

Ken and I had negotiated a ten-year contract with Media Arts Group to exclusively represent its licensing contracts. We opened an office with a small staff in downtown San Jose. Thomas Kinkade was our primary client, but as an independent agency, Creative Brands Group represented many other clients during that time. The business was divided into two distinct areas. The first, the core business of licensing, was left to me to manage. I managed all the Thomas Kinkade licensing and increased the total licensing agreements to over one hundred contracts. In addition, I managed several other brands, including that of New Zealand photographer Rachael Hale, which I ultimately built to almost a hundred licensing agreements. The other focus of our company, run by Ken, was to find and execute investments in new opportunities. Our goal was to take our income from the agency and pay each other very well, along with our staff, but to invest the money we had left over into new ventures. However, because of the extremely successful licensing business, focusing on anything else almost proved to be nothing more than a distraction. Ken also became deeply involved in the Thomas Kinkade art business again, albeit now as an outside advisor to Thom and the revolving door of CEOs.

Unlike the art market side of the company, the licensing side had the opposite mandate. Where scarcity protects art market value, licensing is all built on volume. The more sales the better. You couldn’t overexpose a cottage on a Christmas ornament. The very sales volume supported its popularity and salability. No one worried about the resale value of an ornament or a calendar. It was just a way to get a piece of the artist otherwise not within reach. And Thom’s artwork provided so many images and a never-ending wealth of licensing opportunities that we were guaranteed to do well in the upcoming years. It felt good to go back in as an independent company, with a built-in buffer between us and the everyday ongoing politics.

When we arrived at the Morgan Hill headquarters, Ken and I were astonished. We weren’t prepared for the massive size of the facility and the extent of its elaborate landscape design, including gazebos from Thom’s paintings, flower-lined walkways, and streets with names like Thomas Kinkade Lane. They called the headquarters simply Morgan Hill, with the address 900 Lightpost Way. It felt a little like Disneyland.

The money it must have taken to build Morgan Hill, and the apparent money being made, was staggering. The entire campus was the size of two Wal-Marts. I couldn’t help but think back to my first days at Media Arts when the company was ensconced in the luxurious Ten Almaden address, just days away from disaster. Now it seemed as though Black Monday had never happened. The history of the layoffs, and the memory of nearly losing it all, seemed to have been completely erased. It looked like another big gamble to me.

Like a 500,000-square-foot temple built to the artist Thomas Kinkade.