3

To Nacala

It was afternoon when our plane landed in Maputo’s modest airport. I looked around as we stepped into the hot air and saw palm trees. Strong sunlight was reflected off the pale cement of the runway. The children were so excited. On the journey we had been reading them crazy stories about Soda Pop written by the Swedish author Barbro Lindgren, until they had fallen asleep. Now they were ready for anything. My mother had made them each their own little rucksack and when we entered arrivals, they wanted to hold on to their own passports.

A Portuguese slogan had been painted on the side of the plane: “We carry not only passengers but solidarity.” Indeed, about half the passengers were from aid organizations. People were flooding into Mozambique and we pompously called ourselves “solidarity workers.”

Twelve years ago, I had promised the first leader of the Mozambican independence movement that I would go to his country and work as a doctor. A year earlier, I had been ready to keep my promise but been stopped by testicular cancer. If the children had not been so infectiously delighted with everything, sentiment might have overwhelmed me. Now, they left me no time to ponder.

The border officer checked our passports, looked over the two-year contracts issued by the Ministry of Health and welcomed us with a warm smile. Agneta and I knew that we would be working in medicine and midwifery but our contracts had given us no idea of where. We had agreed to be placed wherever the ministry thought we would be most needed. So, while we waited to pick up our luggage, the big question was: where to next?

We were met at the airport by Ninni Uhrus, our Swedish organization’s local coordinator. Ninni had a perfect plan: she drove us straight to Maputo’s only operational ice-cream parlor. The children’s first African experience was eating ice cream in the shade of a parasol. It went down very well. It also gave me and Agneta time to ask questions.

We would be staying for a few days with a Norwegian couple, who had a child of Anna’s and Ola’s age and, importantly, a garden. Agneta and I should present ourselves at the Ministry of Health the following day to discuss our placement. The principle was never to send foreigners out without having interviewed them and asking every individual what they wanted.

“The officials don’t behave like bureaucrats,” Ninni told us.

The next day we were received by a charming woman from human resources who shared an office with several other civil servants. The health ministry was housed in a modernist building and the brown doors carried proper nameplates.

She had obviously studied our papers with care. Her first question concerned my cancer treatment. Was I well enough to work? Next: were our children happy about living in Mozambique? She came back to that question several times. We told her of our wish to go to Beira, where we had Swedish friends, and she took notes. Beira was the second largest city in the country and had a wonderful beach, which was particularly important to us. We knew that our work would be demanding, although we had no idea of just how hard it would be. To find a place that would be right for everyone in the family seemed critically important.

A few days later, we were back in the ministry, this time to meet a still more senior HR official. He was very direct—regrettably, at present there was no requirement for us anywhere near Beira. He would like us to move as soon as possible to the northern province of Nampula, more precisely to Nacala, the fourth-largest conurbation in the country and the busiest port. There was a desperate need there for doctors and midwives, both in the urban area and in the surrounding rural district. Later, I realized the ministry had planned all along to send us to Nacala but they recognized the need to meet us face-to-face first in order to judge whether we would be likely to cope with the pressure. I was still regarded as an inexperienced medic.

I would be working with Ana Edite, one of the country’s few newly qualified doctors, who already worked in Nacala Porto. Having a colleague meant that I would only be on call alternate evenings, which would be a great advantage. We asked about living quarters but were told that the authorities in Nacala were dealing with that. Our last question: is there a beach? The official laughed, leaned forward and said: “You won’t be disappointed. It’s even better than in Beira.”

He was right. For the next two years, the beach would be a joyous place of refuge for us.

Before leaving the building, we were handed our guia de marcha (marching orders): a document we had to present to the Nacala local authority. As in so many other aspects of life in Mozambique, the military terminology reflected both the past colonial order and the tensions between the newly independent state and some of its neighbors—notably, the South African apartheid regime and Rhodesia, where Ian Smith, leader of the white minority party, was still the prime minister. Both countries were racked by armed conflicts.

Our documents showed that we would be replacing a young Italian doctor who had asked to be moved after just one week in Nacala. It sounded worrying but we were reassured that he had arrived with a “naive and romantic” image of Africa, and had complained that “he had expected to live in the real Africa.” The authorities in Nacala would have been understandably offended by the implication that large towns were not part of “real Africa.”

Filling in a growth chart

I met that young doctor a year later and he admitted that, at first, he had been rather naïve. However, the real reason he had asked to be moved was the exceptionally heavy workload. Nacala was a big town of about 85,000 people, while its large rural district had a population of more than 300,000. The entire area was served by one hospital with around fifty beds.

Within a few months, I would be the only doctor responsible for this gigantic community.

All that was in the future as we drove toward Nacala. Our first encounter with it was in the shape of a shantytown crowded with mud huts with straw roofs. It grew more densely populated the closer we got to the city center. The road was lined with cashew trees and palms, and, between the trees, paths wound their way in among the shanties.

We were on the high plateau but soon began to sense we were coming to the sea. On our right appeared the so-called Cement City, a wealthier part of Nacala, where villas and three- and four-story buildings had been built with cement produced by the town’s own factory. Farther downhill the ocean spread itself out in front of us. The football field and the hospital were on one side of the bay, and high, forested hills rose on the other.

Nacala had a pharmacy and a post office but its health service was nowhere near adequate. As recently as fifteen years ago, the town had not really existed, so there were hardly any old houses and no one in the adult population had been born there.

We had been allocated a pleasant, one-story cement house. It needed some work, including an internal coat of paint, but because of the central planning system we were not allowed to pick our own color. There was just one option—pale blue.

Our part of town had been built for the Portuguese population in the years before independence. Along the road from our house to the hospital were rows of little shops selling mostly tools, a paint shop with hardly any goods for sale, and a coconut stall.

My doctor colleague, Ana, had told me firmly that I was to be driven to work. A car would come to collect me at ten to eight every morning. But the driver turned up almost an hour late on the first morning, so I decided I would walk to work from then on. The hospital staff protested but I insisted and I was thrilled as I set out the next morning: here I was, walking to my new job, and there was so much to see along the road.

Someone greeted me pleasantly before I reached the garden gate. Turning the first corner, I noticed that most of the other pedestrians, regardless of age, stopped when they saw me. There were a lot of people out and about, and everyone stared at me intently. When I was about to pass anyone, they greeted me politely. This carried on all the way to the hospital and, when I walked home in the evening, it happened all over again. The attention made me feel uncomfortable but I assumed people would get used to me. After a few days of staring and greeting, I asked Mama Rosa what was wrong with me. Mama Rosa, a midwife, had already become my closest friend among the staff. She was older than the rest, self-assured and experienced.

She laughed: “You are white. You shouldn’t be walking. Ana told you to wait for the car.”

I thought she must be exaggerating and convinced myself that people would get used to seeing me walking to work within another week.

Then I had a new idea. It came to me when I opened the enormous wooden crate full of our Swedish things—all possessions we had been recommended to pack before we left. It had been dispatched to Maputo by cargo ship in good time, Ninni had arranged for it to be transported to Nacala, and it arrived for our first weekend. It felt like Christmas for the whole family.

We spent the first Sunday in our new home unpacking our treasures. The children were overjoyed at finding their Lego. Agneta sorted out our clothes and I started to fit together the two bicycles I had taken apart as best I could. We had realized that our salaries wouldn’t stretch to buying a car and reckoned we might anyway be more easily accepted by our neighbors if we didn’t come across as wealthier than everybody else. Some Mozambicans could afford cars but they were few and far between. Besides, we had bikes in Sweden and used them much more than our car. Reconstructing the bikes gave me a strong feeling of being at home and they worked just fine when I tested then in the garden. It was a happy family that went to bed after the first weekend in the new home.

The large wooden crate has arrived

Monday morning, I was late for work when I set out. Still, I had my bicycle and would cover the distance faster. As I swung out through the gate at speed, everything seemed to have fallen into place: my family had a house to live in and I was cycling to work.

It took me only a few seconds to grasp that the strangely powerful noise I heard from behind me was not a truck with a broken silencer—it was peals of laughter. I had to have a look. People in the street, who had greeted me so politely during the past week, were pointing at me and killing themselves laughing. As I cycled toward the hospital, those behind me called out to alert others. I saw grown women literally falling about laughing and twitching.

The laughter pursued me onto the main street. By then, I was deeply embarrassed. What was so amusing? I checked my flies, and that I had nothing in my hair or on my face that could attract attention. Probably blushing, I reacted by pedaling faster, but that was apparently even funnier. I passed a queue of patients and their relatives, waiting in the yard in front of the hospital. To a man and woman, they all collapsed, screaming with laughter. The noise was so loud that some of the hospital staff came running out before I got off the bike.

Luckily, as it turned out, Mama Rosa was among them. She didn’t laugh and instead eyed me seriously. We retreated to the emergency reception area where we could talk in private for a moment. I was confused and at a loss, somewhere between laughter and tears.

“Why is everyone laughing at me?” I almost shouted.

“Why did you cycle to the hospital?” Mama Rosa replied.

“Because that’s how I get to work in Sweden.”

“You’re working in Nacala now and here people have never seen an adult white man who cycles to work. No one from the hospital staff does. The Portuguese used to give bikes to their children. And, yes, there was one Portuguese man who lived uptown and used to cycle when he had had too much to drink.”

“Come on, it makes sense for me to cycle. I’m not Portuguese. Besides, Mozambique is supposed to be independent now.” I was close to becoming angry.

Mama Rosa put her hand on my arm and answered: “You must listen to me. It isn’t about being sensible or not. You’ll become a joke and then you won’t function as a doctor here. I’ll tell the cleaner, Ahmed, to wheel your bike back to your house. You can use it to take your children on outings but never again to get to the hospital. We must stop chatting now. I have a woman in the delivery room. She gave birth at home, the baby died and now she is very ill. She has tetanus.”

Tetanus is a terrible affliction. I knew that I had to convince all the pregnant women here to be vaccinated and I would fail if I became known as the local clown. I had to choose. I decided that cycling was out of the question if it affected my credibility, especially when introducing new ways of protecting the population.

It would not be the last time I had to ask myself: which changes are most important? And which changes are easy to make?

A year later, we had succeeded with our vaccination program and no more women or newborn babies were arriving with tetanus symptoms. But I still couldn’t cycle to work. A mantra had stuck in my mind: “At first, change only what must be changed. Let everything else wait.”

My first friend from Africa, whom I’d met years before I moved there, would help me toward new ways of working and thinking. He came from a village in the countryside. His three older siblings had died as newborn infants. When he was born, his mother gave him the name Niheriwa. It was a temporary name—a kind of standby in the local culture, when it was feared that a child would soon die. It meant something like “the grave is waiting for you.”

But Niheriwa had survived. His parents, who ran a small farm, worked hard and managed to keep the boy at school. He did exceptionally well. Throughout his life, Niheriwa kept his “temporary” name because, he told me, he wanted to honor his hardworking mother and remember that all life is fragile.

Niheriwa became fluent in ten languages and was so successful at school that he was accepted at a Catholic seminary, expecting to be ordained. He ran away from the seminary as soon as the struggle for an independent Mozambique began, and walked all the way to Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, to enroll at the independence movement FREMILO’s headquarters to join the fight for freedom.

We were in contact for the first time in 1967, when he replied to a letter I had sent to FRELIMO, asking for information. After he had been working in the office for a few years, Niheriwa’s ability was noticed and he was offered the opportunity to study in East Germany. We had kept up a sporadic correspondence and he had visited me in Sweden during his student years in Europe. He eventually graduated as a qualified mining engineer, one of the very first from Mozambique in Germany.

Chance brought us together again in 1979. My family and I were queuing in Maputo air terminal to check in for the flight to Nacala and just moving on when I spotted Niheriwa in the next queue along. We hugged and greeted each other happily.

“But where are you going to live?” Niheriwa asked.

“In Nacala.”

“Then I’ll come and see you!”

Niheriwa had just returned home and was going to take up a post as director of a mine in his native province. As a big port city, Nacala was where imports for and exports from the mine would be shipped.

He came to see us regularly over the subsequent years. Niheriwa was a tall, heavily built man. His expressive face constantly changed, shifting through a whole range of feeling, from great seriousness to vivacious humor. He was a good, dependable friend and advised me on many things. He taught me a trick to stop ambulance drivers from cheating the hospital by trading unused spare parts for old ones. Above all, Niheriwa guided me in the extremely tough task of being the boss of a crew of people in a very poor country, where hardly anyone had the training required for the job they were employed to do.

He also explained why I shouldn’t keep talking all the time. The best thing, he said, is to stay silent and let other people talk. Ask questions but focus on listening to what people say in reply and try to get to what really troubles them. Once everyone has had a chance to speak, the boss should think things over. The pause will make his staff nervous but, when he breaks the silence, he will tell them he understands what they have said and that this is what they, as a team, will do. Then he will describe how it will be done. Niheriwa insisted this was how to become accepted as the leader and establish discipline.

One weekend, when Niheriwa was staying with us, we went to the beach. Nacala has one of the best deep-water harbors on the east coast of Africa. A curving peninsula creates a wide, protected bay where even the largest ships can enter the harbor. One of the Indian Ocean’s most wonderful beaches is a little farther along and it was our goal that day.

When we arrived, we parked in the shade of a pine tree, climbed out of the car and took in the view of the many hundreds of meters of sunlit beach in front of us. There were more people on the beach than usual, maybe twenty families.

“It’s a shame that this place is so busy today,” I said to Niheriwa, who was standing next to me. “Let’s quickly try to find somewhere peaceful.”

He sighed heavily, grabbed my arm and got serious: “Look over there at Nacala, with its more than 80,000 inhabitants, just a few kilometers from where we are. Roughly half the population of the city are children but here, maybe forty children are on the beach. One child in every thousand! You call that too many? When I was a student in Germany, I’d often go to the Baltic coast near Rostock. Every weekend, the beaches would be full of children, many thousands of them, playing with their friends and family, and having a great time.”

Then he let go of my arm, walked to the car and helped our children carry their toys and swim fins. I picked up the rug and the sun umbrella and Agneta took the picnic basket. We only had to walk a short distance to find a place to settle on what was actually an almost empty beach.

Time and time again, my African colleagues have surprised me by demonstrating how my mind keeps following the same thought patterns as most Europeans when they arrive in Africa. Their intentions and Niheriwa’s were the same: to remind me (and all of us Europeans) that, however engaged we are in the struggle to free Africa of misery, we seem hopelessly lost when faced with an Africa where people have the same dreams for their lives as we do for ours. Why should it be so hard to accept that most families, wherever they live in the world, want good lives for themselves? Want to holiday in faraway places? Spend contented, relaxing days on the beach?

One day in the hospital, late in the afternoon, an elderly woman with a leg fracture arrived, carried in by her two sons. She had not managed to get out of the way in time when a tree was felled in her village. The ends of the broken bone were protruding through her skin and I would have to force them back into place. The infection risk was serious, and potentially fatal. It would be difficult to get the bones joined up properly, especially since we had no X-ray machine and had just run out of anesthetics. She was warned that the treatment would be very painful. I cleaned the wound carefully. Two staff nurses then took hold of the patient under her armpits to pull her in one direction, while the strongest junior nurse was told to pull the foot in the opposite direction. After much grappling I managed to line up the fracture surfaces so that they fitted and supported each other. I closed the wound, stitched the skin margins and put the entire limb in a plaster cast, from groin to toes. Finally, because the wound would have to be dressed, I removed the area of plaster covering it. The procedure had taken two hours and had caused the patient intense pain. I left instructions that she was to be put on an antibiotics drip, and told her that she had to stay in bed for a week and not put any weight on the leg.

That evening, I went home feeling a certain sense of accomplishment. The treatment had been an orthopedic procedure far beyond my technical qualifications.

When I arrived at the hospital the following morning the first person I saw was the old woman. She was standing in the doorway, waving to me. Upset, I rushed to speak to her.

“You must stay in bed,” I said in Portuguese.

But she only understood the local language Makua, so I tried to explain in sign language. A tearful nurse had been trying to persuade the patient to get back to bed. She translated what the patient was saying: her hens might get stolen so she had to get back home.

“Look, the cast is strong,” the old lady said, banging her foot on the floor for emphasis.

The entire hospital staff in front of the clinic—qualified medical staff in white and untrained staff in blue.

When I looked down at her foot, I discovered that something had gone very wrong: the immobilized foot was pointing sideways instead of forward, as it should. At the back of my mind, I heard the consultant surgeon’s warning from when I trained in orthopedics: “Check alignment before you put on a plaster cast. With a broken leg, get the relationship right between foot and knee. A patient in pain tends to twist the upper part of the leg inward. You have to pull the bits into their proper place before putting on the plaster.”

I had made a classic mistake and fixed the foot pointing outward. I felt terrible that I had done this.

Curious patients and their relatives stood in a ring around us, watching and giggling once they realized that the old lady’s foot was pointing the wrong way. I asked the nurse to translate my advice: I would have to remove the plaster, pull the leg into the correct position and put on a new cast. I twisted my right foot outward and lumbered about, surrounded by sniggering onlookers, as an animated illustration of how she would be limping for the rest of her life if she didn’t let me reset her foot.

But when I was done with my performance, the old lady smilingly put her hand on my arm. The nurse translated again.

“Doctor, what you’re showing is as much as I ever hoped to be able to do. I can feed my chickens and take care of my grandchildren. I am happy to have survived. To walk about like that is fine. Not to worry, you have other patients to cure today. I just came along to get some pills from the nurse and then wait for you so I could thank you before I go home.”

The people around us nodded and mumbled in agreement as she shook my hand. Then they stepped aside to let her cross the sandy yard in front of the hospital entrance. Almost fifty of us looked on as her footsteps in the sand formed a trail like the track of a large tractor tire.

I never saw her in the hospital again but learned later she had survived. The plaster had cracked and fallen off after a month and her foot was badly out of line. Still, her chickens were all right, so she could give her grandchildren eggs to eat now and then.

Patients, relatives, and the hospital staff taught me how to put up with the knowledge that I could not achieve everything I set out to do. Also—one of hardest things for me to accept—that, in the end, it was up to the patient. Slowly, I grasped that everyone, even the poorest, who were often the most superstitious, was fundamentally wise when faced with the toughest decisions of their lives.

My mentor, Ingegerd Rooth, who had been a mission doctor all her life, had told me: “When you work in a place of extreme poverty, don’t try to do things perfectly. All you will accomplish is wasting time and resources that could be put to better use.” In effect, this was the same lesson that the old lady with her broken leg had taught me.

That lesson generated a new way of working: the two-by-two table. The idea crystalized for me about a month later, on a Sunday night after another marvelous day on the beach. I had read the children a bedtime story and gone into the sitting room to work. It was a reasonably cool evening and there was no need for the fan to be on. I settled down at the cleared dinner table and started to look over the past week’s “de-stressing list.”

I had taken to carrying a small notebook in my pocket and grabbing whatever pen was at hand to write down a word or a brief phrase as a method for staying calm whenever I identified something that I felt must be changed in the provision of care or the structure of the organization. At first, my insistence on instantly correcting anything I thought out of order had made me unbearable to the people I was working with, and to myself as well. The solution I had arrived at was to confine myself to writing everything down.

That Sunday night, I planned to go through my notes and prioritize the things that needed to be changed. I began by writing a clean copy of the list of problems I had come across. Some problems were insoluble and I crossed these out at once. Next, I needed to resolve the rest of the problems. I drew a large square divided into four fields on a sheet of paper and wrote EASY and HARD over the two vertical columns. To the left of the two horizontal rows, I wrote IMPORTANT and NOT IMPORTANT. Now I could fit my notes into four groups. After pondering for some twenty minutes, the upper left field, EASY and IMPORTANT, contained four items. The first one was “separate the dressing of clean and infected wounds in outpatients’ minor injuries clinic.”

On Monday, I planned to have a word with Papa Enrique, the hospital’s oldest nursing assistant and a very kind man.

That Monday, I crossed the hospital yard after the morning ward round and entered Papa Enrique’s small premises, located in the middle of the long building that housed outpatient care. His was probably the only space in the entire hospital that did not smell bad. Everywhere else, the air was stale or worse. Some patients had suppurating wounds or rotting body parts. Others simply had no facilities for washing their clothes. Some of the bedridden patients did not get a bedpan in time. Relatives who came to help with feeding spilled food on the floor. Everyone, whether wearing shoes or not, brought in sand because the whole town was sandy underfoot. The need for cleaning was constant but our resources only sufficient for one daily round by the cleaners. We lacked effective ventilation and while some days could be suffocatingly hot, air humidity was too high for the towels to dry on the washing line during the rainy season. Despite all this, we fought to keep up appearances and had agreed there should be vases with freshly picked flowers in all the windows.

Going into Papa Enrique’s treatment room, the strong smell of cleaning fluid hit my nostrils the moment the door opened. On one side of the room, around a dozen patients were lined up on a low wooden bench, waiting to be seen. On the other side, a patient sat on a tall table covered by a stained, once-white plastic sheet. Papa Enrique leaned over him, bandaging his hand.

He straightened up at once and greeted me pleasantly. I told him that I had a small change in mind: to organize his patients so that he could attend to the clean wounds first and then move on to the infected ones. He looked troubled and said he wasn’t sure what I meant by clean wounds being different to infected ones. My attempts to explain got us nowhere, so I told him to finish the bandaging and then I’d show him the difference.

Two of the waiting patients had lower leg wounds, and I asked them to sit next to each other on the bench. One of them had a recent, substantial burn. His face looked pained as he told me how he had knocked over a large pan of boiling water that morning.

“This wound isn’t infected and it is very important you don’t cause an infection when you clean and bandage it,” I instructed Papa Enrique.

Then I turned to the second man with a lower leg wound. At the upper edge of the wound, pus flowed from a small hole. His was a tragic case of osteomyelitis. The pus was forming inside the infected bone and draining steadily through a fistula, a channel through the tissues.

I asked Papa Enrique if he could see the difference between the large but superficial blisters on the burned skin and the small hole where the pus was coming out.

He inspected the wounds carefully, looked up at me and said in a worried tone: “I can’t see any hole.”

“What are you talking about?” I almost shouted. “Can’t you see the hole with the pus coming out?”

“No, doctor. I don’t see so well anymore,” he answered quietly.

I was quite taken aback. Then I remembered that my glasses had quite strong lenses because I had been farsighted since childhood. I put my glasses on Papa Enrique. He glanced at the legs of the two patients and gestured with both arms—now it was his turn to speak almost at shouting pitch:

“Now I see it! That one has just blisters but here there’s pus coming from a small hole.”

He took the glasses off, looked again and then held them up to me, exclaiming: “Without these, I can’t see the hole.”

I brought my spare glasses back after lunch and gave them to Papa Enrique, who thanked me very warmly. The gift was hugely important to him. I interrupted his flow of polite gratitude to show him something.

“Take a look at these two sets of notes. This is what I’m going to write for every patient before I send him or her along to you for wound dressing.”

The messages were straightforward: one said CLEAN WOUND, and the other said DIRTY WOUND. I handed both notes to Papa Enrique, who took them but looked troubled again.

“It’s really not at all difficult; don’t worry,” I said. The room was empty for a moment and I pointed at the bench, explaining that everyone with a clean wound would be seen first. Every morning, patients with dirty wounds had to wait until those with clean ones had been looked after. Between every batch, the bench should be cleaned with strong disinfectant.

By now, deep furrows had formed on Papa Enrique’s forehead. Embarrassed, he murmured his answer: “Doctor, I’ve something else to tell you. I can’t read.”

I had been working in the hospital for nearly three months but had failed to realize that almost all the assistants were illiterate. I had just taken a step on the long road toward understanding the complexities of social underdevelopment.

Later that afternoon I complained to Mama Rosa but she cut me short.

“I thought you understood what it was like in the colonial era. Most Mozambicans had no chance of going to school. Those who learned to read landed better jobs than assistant nurse. These days, many attend literacy classes in the evenings. Give us a few more years. Then all the staff will be able to read, even Papa Enrique, especially now that you have given him a pair of glasses. Because if you can’t afford glasses, you can’t learn to read either,” she added.

In the same month that Papa Enrique got his glasses, one of my days at work ended with me filling up our dark green Land Rover with patients. It was at this time the only vehicle we had to help us look after more than 300,000 people (at other times we had two) and tonight we were using it to take several acutely ill patients to the regional hospital in Nampula. It was a two-hundred-kilometer drive and the road, though partly paved, was studded with potholes. To make this particular journey worse, it was raining heavily.

Regardless, the car had to leave as soon as possible because it would be carrying patients afflicted by illnesses I could not deal with in Nacala. One of them was a man suffering from schizophrenia. He had arrived the day before in a florid, psychotic, hallucinating state. His family had grown very scared, tied him up and brought him to the hospital. He needed to be cared for in the psychiatric unit in Nampula. All I could do was give him massive doses of sedative until he was passive and drowsy. Later, he almost lost consciousness, but I had to keep him sedated while we waited for other very ill patients to join us. It took time but I could not send the car off with one patient at a time. The psychotic man would have to stay overnight.

A woman arrived the following day, pregnant and nearly full-term. She was bleeding and I suspected that a low-placed placenta was blocking the passage for the baby’s head. Unless the baby was taken out by caesarean section, she would bleed to death once her contractions started. I made her wait, too, because the Land Rover could hold three patients, and another acutely ill patient might well turn up in the next few hours.

Later that afternoon, a middle-aged man came in with a bad complication to a hernia. The patient had been ignoring the bulge in his left groin for ten years. Now, his intestines had begun to twist themselves around each other, a condition that would likely kill him within twelve to twenty-four hours. He urgently needed an operation. Time for the Land Rover to go.

The driver had it all worked out. The drowsy man would sit in the front passenger seat. The man with the hernia would be on a stretcher in the back, across the seat. The pregnant woman and her relative would sit on the two remaining seats at the back. The relative promised to help the hernia patient when he threw up.

Why would we agree to take the pregnant woman’s relative, an elderly woman, rather than a nurse? The simple reason was that the patient refused to go to a large hospital in a town she had never visited unless the other woman came with her. Mama Rosa decided that the relative should be allowed to go along.

Once the patients’ few belongings had been packed, the vehicle was full. I checked that the driver had a full tank and that the nurse had given the psychotic patient a top-up dose of sedative. As the sun set, our only health-service vehicle was rolling down the main street to begin its three-hour journey to Nampula. Once I had checked that there were no other acute cases to deal with in the hospital, I went home for a calming family supper, hoping the bigger hospital would save my patients. I needed a good night’s sleep. It was still raining and I fell asleep to the sound of drumming raindrops.

Knock knock knock, I heard in my dream. Then I realized that someone was actually hammering on our front door. I pulled on a dressing gown, switched the light on, undid the safety chain and peered outside. A man was standing in the rain. His eyes lit up when he saw me.

“Good evening, doctor,” he said.

I took in the surprising fact that Manuel, our driver, had returned. “Are you back from Nampula already?” I said.

“No, senhor, I’m bringing this tire back. It had a puncture. I need you to help me fix the puncture tonight because I don’t think those people can wait until the morning,” he said, indicating the car tire held under his arm.

Utterly baffled, I asked where the car was. He had left it on the far side of the dam, he said, only fifteen kilometers outside Nacala but still in the middle of the countryside.

“Where are the patients?” I almost screamed.

“Oh, they’re all there, inside.”

“Inside what?”

“The car. The old mama said I had to hurry because her daughter had started bleeding again. That’s why I thought it better to wake you up, doctor.”

Manuel explained that it had taken a long time to get the tire off because he didn’t have a screwdriver.

“Why not put on the spare tire?” I asked.

“This is the spare. I drove on it. Don’t you remember me saying last month we needed a new inner tire? It hasn’t arrived yet.”

By now, the situation was clear in all its horror. My three critically ill patients were stranded inside a car in the middle of nowhere during a stormy night.

I dressed, packed a screwdriver and the damaged tire into our private car and drove to the port, which was open round the clock. I chased up the harbormaster and, after taking the time to brief me on his family’s health issues, he agreed to get a mechanic from the port’s machine workshop to repair the tire. He left me to supervise the work while he went off to find help with transport. He got hold of a truck just about to leave for Nampula despite the pouring rain. An hour later, Manuel and the repaired tire had joined the truck driver in his cabin. I drove home to snatch some sleep.

The next afternoon Manuel returned. I was very relieved to learn that all my patients had arrived at the regional hospital alive.

It was consistently difficult to foresee the different ways that having very limited resources would impact us. Insufficient transport for fuel and medicine, and a lack of skilled staff and decent equipment, didn’t just hamper our ability to achieve what we set out to do; it made it almost impossible to even predict what might be achievable.

On the evening of the day I almost died, I squeezed into the Suzuki jeep, perched on a board between the driver and the front passenger. We had been to a very useful Friday meeting with the regional health service bosses and the heads of each of the eighteen districts in Nampula. A few other medics and I had nagged the organizers to be allowed to go home that night. My only other medically trained colleague in Nacala, Ana Edite, was also with us. We had bought sacks of flour and avocados in the market and packed them away in the car.

The road, which came from Malawi, crossed northern Mozambique and ran all the way to Nacala. It was in relatively good condition but rainwater that had gathered in the massive potholes was spilling over and washing the road’s shoulders away. All along the road, there were scattered villages surrounded by cassava fields without boundary ditches. It was like driving through a forest of low willow shrub.

Cassava, a fast-growing bush, has edible roots, which are a basic foodstuff in many tropical countries, including Mozambique. The roots have a high starch content but can be toxic unless a lengthy preparation process is carried out properly.

The horizon was ringed by beautiful hills shaped like sugar cones and just a few hundred meters high. I felt these hills had been there since the beginning of time.

The driver was an electrician without a driver’s license who was half asleep at the wheel and drove at 110 kilometers an hour. About halfway to Nacala, we were held up because a bridge had collapsed. About fifty meters before the gorge, traffic had been redirected by means of the usual local device—a large pile of twigs and branches. It had to do the job of more conventional road signs because tin signage was always instantly stolen.

In this case, to emphasize the danger ahead, the workmen had added a half-meter-high mud wall running across the road. In this part of Mozambique, the soil is a deep reddish-brown. I was always amazed to see how lovely bare, wet earth looked at sunset.

We had been zooming along in the darkness. Our driver missed the first warning and when I caught sight of the roadblock, we were just thirty meters away from it. I simply howled, unable to find the words in Portuguese.

All our driver had time to do was to twist the wheel. Then he lost control, so that when the car crashed into the mud embankment it was already in a skid. The car rotated and leaped into the air at the same time with a momentum so powerful I was subjected to a centrifugal force. I did not feel upside down, even as the world turned. Green grass up there, dark starry sky down there.

We flew through the air. I’ll die now. I had time to think these words.

Seconds later I was amazed not to have been crushed. The impact had not come. Instead, the car kept gliding on its roof like a surfboard on water. The wet grass and soft mud did nothing to stop it. The forward movement made me shoot out through the gap where the windscreen had been and then continue sliding on my back. Nothing made sense. A few moments later and I was lying quietly in the tall grass. I slowly pushed myself upright with my hands and found myself staring straight into the beams of the headlights. The car’s engine was still running.

My mind fixated on my right foot. It was bare, and the nail of the big toe had gone. My left foot was still clad in its sock and shoe. Almost without thinking, I began to walk toward the car. I came across my right shoe. I put it on. Then I spotted my glasses and put them on. Then, for the first time, I thought about the car. The light glowed, the engine was turning and it was upside down. It will catch fire and then explode, I thought. I had seen what happens in films. Cars overturn and a little later they explode.

So far, I had not had time to reflect on being, seemingly, in one piece. I went to the driver’s side, saw it was empty and stuck my hand in to turn the ignition off. Silence fell.

A calm voice spoke near me: “Why turn it off? It’s completely dark now.”

It was a doctor from one of the other districts. While I had been getting up from the grass and putting on my lost shoe, he had crawled out through the rear door and been able to talk to the others. They were also all right. We noted that the driver was gone. He had run away.

“Three of us have got away with only minor injuries,” my colleague said. “They are sitting behind the car.”

Now we heard wailing from inside the car. Ana Edite was stuck in there, under our sacks of flour and avocados, squashed up against the roof bars. Our shopping was scattered all over and around Ana and our first thought was to get her out by getting it out. We tried to push the car from side to side but Ana screamed in a way that made us realize that was a terrible idea. Then it struck me that we could dig her out of the soft mud. I dug with the help of a key I had found in a pocket. When she had unstuck a little, we slowly pulled her forward, feet first.

Then we stood there in the middle of the night. It could be half an hour between cars on this road in the Mozambican countryside.

The people who lived in the huts on the other side of the road came out with paraffin lamps so we could have a closer look at people’s injuries. I examined Ana, who said she had bad abdominal pain on the left side. I understood that she was bleeding internally, as I sat with her, checking her pulse while we waited for a car. Her pulse rate was increasing, as it would initially if the patient was losing a lot of blood.

I looked for damage on her body, including on her fingers and face and under her hair. I couldn’t find anything and could not do anything for her. This is a matter of luck, I thought. If she is unlucky, she will die quickly. If she is lucky, we will get her to a hospital in time.

“They are on the way, and they’ll take you to Nampula,” I told her, to calm her down.

“My husband, you must get in touch with him,” Ana said.

Then a car did come along. One of my colleagues, who was only a few kilometers from his own hospital in Monapo, knew the family in the car. Later the same night, Ana Edite was on the operating table. She had years of rehabilitation to come, and a poorly functioning foot that she would have to cope with for the rest of her life. But she survived.

I had been so grateful to the villagers who had crossed the road to light us with their paraffin lamps that I tried to give them a sack of avocados as a thank-you gift. A crazy idea, Ana Edite’s husband told me much later. Every one of them was a small-scale avocado grower, he explained, laughing heartily.

I cursed myself that night because by helping to arrange the transport I had broken a rule I knew only too well: you should never drive at night in a poor country and especially not after heavy rain. I had lost several friends that way. However, it was a relief to know that Agneta was not waiting anxiously for me at home. She did not expect me until lunchtime the following day. I slept at my colleague’s house, and in the morning washed my foot and rinsed my torn shirt.

When I was dropped off outside our house, Agneta was standing in front of the open kitchen door, smiling. Tears welled up in my eyes as it struck me how close to death I had come. We stood, holding each other tightly, just inside the door. But that intense moment was not to last because there was a knock on the front door. Irritated, Agneta went to see who it was.

In trooped the Grupos Dinamizadores, the local group of Party reps. They turned up on people’s doorsteps on Saturdays to check that everyone had tidied up properly. The point was to avoid being found out as a xiconhoca—that is, a filthy counter-revolutionary who was probably trading on the black market.

Agneta tried to explain that this was not a good time for an inspection but the Grupos Dinamizadores paid no attention to her. They told me to go and rest in bed instead of standing there trying to explain things to them, so I lay in bed sobbing while they poked about all over the house. In the end, they took an interest in only one thing: the sack of avocados. This was understandable, because it was an unusual find: we had never during our two years in Nacala been able to buy avocados in the town. Had we acquired it on the black market?

As this utterly absurd night and day drew to a close, I was struck by a fact that would become critical for our entire continued existence in Nacala. The thought crept into my mind when I had calmed down after a few hours at home: Ana Edite would not be coming back to work. I would be the only doctor in the whole district. I would be on call round the clock.

The health service’s resources were already minimal and the care needs maximal. From that day on, as I went to work in the mornings, I thought more and more often about how different the health statistics were in Sweden. My thinking followed these lines: “Today, my day’s work will be the equivalent of the work of a hundred doctors in Sweden. What am I to do? Examine each patient a hundred times faster or pick one out of every hundred patients?”

Every day, I somehow had to find a compromise between these two options.

As a matter of fact, very many sick people never saw the inside of any care facility, let alone the hospital. True, it was rather small with its fifty or so beds, which were always full. Some inpatients even had to lie on the floor. Still, what care we could offer was not limited by the number of beds. The real limitation was us, the staff—in quantity as well as quality. I had a little more than two years of professional experience. The handful of Mozambican nurses had four years at school and then trained in nursing for one year. More than half of the rest of the staff were illiterate.

If this had been Sweden, I would have been one of a hundred medics responsible for the care of this population. Also, the child mortality rate would have been a hundred times smaller. My challenge now was to get a grip on what our resources actually were and how to use them in the best possible way. Beyond the hospital, it was harder still to get my head around the nearly nonexistent care resources for the rural population. Practically all of them lived in conditions of extreme poverty. Their strength and energy were concentrated on finding enough to eat and, even then, there were many days when they would go without.

Again and again, I was forced to recognize how unrealistic my ambitions were. Everyone, patients as well as hospital staff, tried hard to show me what was possible and reasonable. It was very far below the level of expectation that my Swedish medical education had instilled in me. A need one hundred times greater than in Sweden had to be met using one percent of the resources. That meant about ten thousand times less resource per patient. Ten thousand!

I admit that trying to adjust to and cope with this differential felt like being in a post-traumatic state. I called it “my four-zeros brain trauma.”

The psychological state of generalized scarcity taught me lessons about myself. I had previously thought that I led my life guided by certain unshakable values. I believed, for instance, that you must not kill a thief. That is, until I was pushed beyond control. One night, someone unscrewed the headlight covers on one of our two ambulances and stole the bulbs. Now that ambulance could not be used after dark. That theft filled me with an explosive hatred. I fear that I might have killed the thief if I had caught him. Just as I might have killed the creep who stole our ducks.

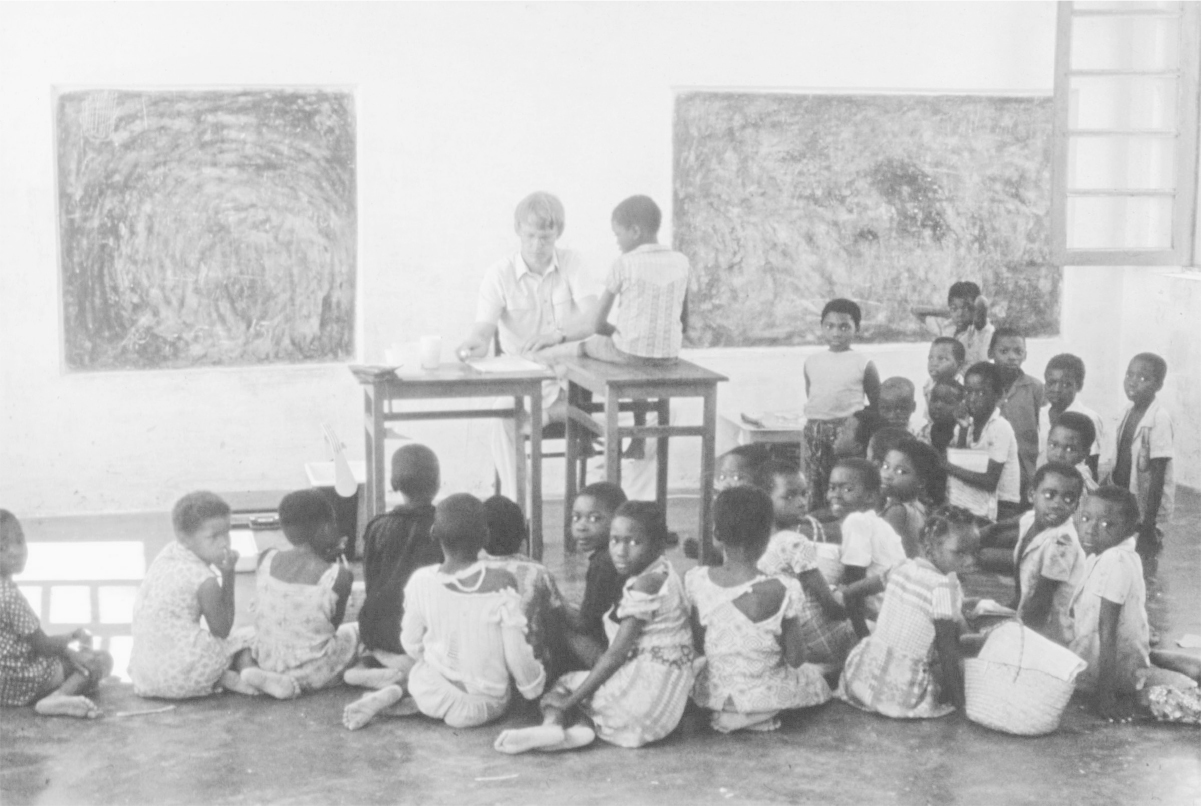

In a school room, with the children

The children enjoyed the ducks but our main reason for keeping them was to have a small but valuable source of meat in a centrally managed economy with erratic supplies of food. One night, the ducks were screeching so loudly that the row woke Agneta. She looked out through a window and saw someone breaking into the duck house. She called out and the thief ran away. I jumped into the car and chased him. When I spotted him in front of me on the road, I put my foot down and followed him around a corner. An echo was bouncing around in my head: “That bastard won’t get our ducks.” Until I realized that I was about to run him down and kill him. I must pull myself together. The thief slipped into a side path and disappeared. He was lucky. The judicial system was failing and people often took justice into their own hands, sometimes brutally. Theft caused immeasurable damage to people and the punishments could be vile. One common method was to tie the thief’s hands behind his or her back with lengths of rubber cut from inner car tires. Unless someone cut the straps quickly, the blood stopped circulating and the hands became permanently useless. I had quite a few people with tied-up hands coming into the hospital and was normally furious at having to waste time on them.

The cruel dangers of living in extreme poverty were also reflected in other injuries we had to deal with in the hospital. The town had only one shop which sold food, the loja do povo or “people’s shop,” and its shelves were often empty. Now and then, it got a consignment of fish, which was sold via the loading bay because the goods entrance had a big steel door. The pressure of the crowd of customers would have been enough to break the display windows if they had traded as usual. Instead, the shop manager opened the steel door and admitted some fifty people at a time. The crowd soon became chaotic, and someone always got badly squashed. On days when several bone fractures were queuing at the hospital to be fixed, we knew that the state shop had been selling fish or sugar.

The car stopped outside our house and our Swedish friends were still laughing as they climbed out. It had been easy to find us.

“We did just what you said and asked people where the doctor lived. They all pointed to the right place at once!”

They were a couple of about our age who had come to stay with us for the weekend. The same organization that had recruited us had recently arranged for them to come to Mozambique and work in the large regional hospital in Nampula, two hundred kilometers from Nacala. The husband had a post as the pediatric doctor on the neonatal unit.

It was fantastic to have visitors. We were hungry for conversation and especially keen to talk to people who could understand how we lived now. Lunch went on and on because we had so much to discuss. We spent a lot of time comparing our places of work.

“Honestly, none of my nurses have any specialist qualifications,” he told me.

“Half of my staff can’t read,” I said. And so it went. We kept talking past each other in a rather male way.

We unquestionably worked with very different levels of staffing and equipment. That was how it had to be, because the regional hospital also taught clinical students, so the care had to be of a reasonable standard.

Our talk was interrupted by an energetic knock on our front door. Because the telephone was out of order, a nurse’s assistant had walked from the hospital to fetch me. A very ill child had just been admitted.

My friend borrowed a white coat from me and came with me in the car. When we stepped into the small room for acute admissions, we met the terrified eyes of a mother trying to breastfeed an emaciated infant. The baby girl, who was only a few months old, was almost unconscious and her eyes were sunken. Bad diarrhea, the nurse told me. When I pressed the skin over the child’s belly using two fingers, the fold persisted long after I had taken my fingers away. The diagnosis was obvious: she was dying from dehydration and was too weak to suckle. I took a thin tube, introduced it via her nose into her stomach and told the nurse which type of fluid replacement to use and how much.

My friend was shocked. When I was almost done, I felt his hand gripping my shoulder and he pulled me out of the small room, stopped outside in the corridor, and looked at me with an infuriated expression.

“What you just did was utterly unethical! That baby did not get the right treatment. You’d never have done it to your own child. She was very sick and should have been hooked up to an intravenous drip immediately. You are risking her life by giving rehydration solution via a nasogastric tube. She could start vomiting it up and lose the water and salts she needs to survive. I suppose you’re taking the quick way out because you want to get to the beach before supper.”

He was unprepared for the kind of medicine that the brute facts had forced me to accept.

“No, what you saw is the standard treatment in this hospital. This is how we work. We never do better, because of the resources and the staff we have. And that includes me. I have to get home in time for supper at least a few evenings every week, otherwise neither I nor my family would make it through another month. It might take me half an hour to get a drip set up for this child. And there’s a high risk that the nurse won’t be up to keeping an eye on it and the baby will get no fluid at all. But the nurse can do tube rehydration, it’s more straightforward. You must accept that our level of care is only as good as possible.”

“No, I can’t,” my friend insisted. “It is unethical to manage that baby with fluid fed by nasogastric tube. I am going to put her on an IV drip and you can’t stop me.”

I didn’t stop him. Instead I brought him the thin needles suitable for the veins of small children. We had saved some up in a cupboard in the doctors’ office. Despite many attempts, my friend could not get a needle into any of the baby’s veins. Next, he wanted the necessary equipment for incising, to expose a deep blood vessel. He set about this minor operation and our nurse did her best to assist him. I left them to it, went home and had supper with my family and my friend’s partner. My work recently had been relentless and I had not eaten an evening meal at home for several days.

Afterward, I drove back to the hospital to pick up my friend. After much effort, he had finally got the drip up and running. The baby seemed a little better but still would not suckle.

That evening brought no rest. Once the children were asleep, my friend and I sat on the sofa and talked deeply and very honestly about the ethics of what we were doing.

“You must always do your best for each and every patient who wants to be seen,” he said.

Numbers are so important in ethical discussions. It is misleadingly easy to define what is right and wrong when you speak about one patient at a time.

“I don’t think so,” I replied. “It is unethical to spend all available resources, including time, on trying to save only those who have been admitted to the hospital.”

I went on to explain that more childhood deaths would probably be avoided if I spent more time on improving health facilities at street level—that is, care in local health centers and small clinics. My task must be to do all I could to improve child survival and health in the entirety of the town and its surroundings. I had become convinced that most of those who died from preventable causes had stayed at home and never come to the hospital. If we were to concentrate all our resources on making the hospital as good as possible, fewer children would be vaccinated, fewer competent members of staff would serve in the existing health centers, and the effect would be that, overall, more children would die. I was as responsible for the children I did not see suffer and die as for those I did see. Given our poor resources, I therefore had to live with the low level of care we offered at the hospital.

My friend disagreed, as most hospital doctors—and probably the majority of the public—would. He insisted that a doctor must do everything in his or her power for every patient they encounter.

“The supposition that you might be able to save more children somewhere else is simply a cruel theoretical guess,” he said.

At about this stage in our debate, I stopped arguing but thought: “It cannot be more ethical to act on your instincts than to make a thorough investigation into how and where you can save most lives.”

This thought stayed with me throughout the following day, as I tried to help a woman give birth. Her labor was into its second day. The baby was stuck. Its arm had been jammed and someone had tugged at it in an attempt to get the baby out. Now, the arm had grown dark for lack of blood supply. The hand was ruined and would have to be amputated. I could pick up the fetal heart sounds, so the child was still alive, but the mother was running a high temperature. Her uterus might rupture at any time.

I examined her and realized the baby’s head had engaged in the birth canal. I could feel it just a few centimeters up. I had to hurry.

As a delivery progresses, the clinician—usually the midwife—has to check various functions hourly and enter the data into a so-called partograph. I had made my own partograph with a rule in mind that said: the sun must never rise twice on a woman giving birth. My version was a sheet of paper painted black for nights and left white for days. On the ward round, you tore off a piece of the day or the night. When the sheet of paper was gone, you had to act.

Labor that was continuing when the third twenty-four-hour span was about to begin meant declaring war—the baby must get out somehow. The mother was correspondingly a war victim requiring emergency surgery, and I was a war medic practicing the medicine of the disaster zone. My job in Nacala forced me to work in that spirit from time to time.

“Now what do I do?” I thought.

It was clear to me that I was going to have to kill the baby to save the mother. More specifically, I was going to have to carry out an extraction by dismembering the fetus. I had no proper instruments so I went in with a closed pair of scissors and drove their tips into the fontanelle. The skull came apart and the fetal brain fell out. The baby was now dead. I applied clamps to open up the passage and managed to get the child out, arm first, without the mother’s uterus rupturing. Next, it was crucial to fix a catheter in her bladder. Otherwise the mother ran the risk of developing a cloaca—a breach in the wall separating the vagina from the anal canal, which would allow feces to pass out through the vagina. One usually fixes the catheter by inflating a balloon once it is inside the bladder, but this time I had to be very careful. I used stitches to hold it in place.

The mother was looked after as carefully as possible. And she made it. When well enough, she returned home to her other children. However, having to kill a viable full-term fetus in order to extract it and save the mother is very demanding and very challenging. Did I make the right decision?

Yes, it was the right thing to do in this case. Learning how to make such judgments is hard but it is much harder to act accordingly. Labor is especially dramatic. When the process begins, you are with a healthy woman longing to see the child she loves. Forty-eight hours later she is in deepest hell and close to death.

What to do for her? And what not to do? To dare to make these decisions in the moment, it is crucial that you have explained to yourself exactly which principles you will act on: why your choices will be such as they are. I was appalled at what I had had to do to save this mother, but I knew it was the right decision.

At the same time, thinking back to the dehydrated baby of the previous night, I recognized that, for me, it had become a grim necessity to compare the number of deaths in two groups of children: Nacala children who had been brought to the hospital versus those who were kept at home. Despite our limitations, we had improved the care we offered those who were seen in our hospital, and the proportion of children dying was slowly declining. People seemed to have noticed this, because the number of children we saw was steadily increasing. Most of them suffered from life-threatening conditions such as malaria, pneumonia, and diarrhea. Often, they were weakened by malnutrition, which was far too common, as well as by anemia due to hookworm infections.

Over a year, about a thousand children stayed in the hospital, roughly three new inpatients every day. The others were treated and allowed to go home. All the children admitted were severely ill and, of that group, one in every twenty died despite our best efforts. In other words, a child’s death was a weekly event in the hospital. Almost all of these deaths could have been prevented if we had had more staff and more resources.

I shall never forget what it was like to try to save young lives from the four most dreaded child-killers: pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, and measles. How we could have just minutes to get enough saline solution into dehydrated children with diarrhea before it was too late. How intensely I hoped that the intramuscular injections of penicillin would be given in time to save young patients with pneumonia.

Even so, my most powerful memories are of the unconscious children suffering from advanced malaria, an illness that in the course of a day can turn a healthy child into a terminally ill patient. Would our injection be enough to save them? They often needed intensive care of the kind we simply could not give them. During the day, a never-diminishing queue of sick children and their relatives snaked across the hospital yard. The hot unshaded space filled up with mothers holding their suffering children, waiting for them to be examined. Often, one glance was enough to grade their state of health: some children were sitting upright while others were utterly limp.

Doña Guita, the only one of our nurses to have six years of school education and two years of clinical training, sat at the front end of the queue. She was a star. Her task was to place every child into one of two groups: ill but well enough to go to the waiting room, or very seriously ill, in need of a hospital bed and often running a very high temperature. The second group needed immediate treatment and were sent across the yard to the emergency reception.

The mother’s eyes often revealed the extent of her worry. When her child was so weary it would no longer breastfeed, a mother’s gaze held only desperation and fear of death.

We had thermometers and always recorded temperatures; some children with malaria had a fever of almost 106 degrees, significantly higher than a normal body temperature of 98.6 degrees. I would ask about the breathing and the mother might say, “The breathing is fine, only my child is so hot.” I learned the key phrases in Makua. He coughs blood. Tummy hurts very badly.

It was important to look properly at the child. Not being able to make eye contact was a bad sign. I crouched in front of the mother, or sat on a low stool, carrying out the examination while she still held her child. It reassured the mother. I wanted the contact between me and the mother to be as close as possible and asked her only brief, calm questions.

Mostly, the diagnosis was malaria. It could become life-threatening at terrifying speed, but the right medication could turn it round in a few hours. Pneumonia behaved in the same way.

I have a strong memory of one particular late session in the emergency reception room. It was raining outside. A despairing mother held her two-year-old son in her arms. The father, who looked just as sad, stood next to them. The little boy was breathing very quickly, had a low hemoglobin value and was extremely pale. He would not get well unless given a blood transfusion as well as medication. But the hospital did not have a blood bank or any other resources for collecting blood from anonymous donors. When required, we would take blood from a relative with a blood group that was compatible with the patient’s.

“But I can’t give blood to my child,” the father said.

“Why not?” I asked. We were pressed for time.

“Someone in my family might need blood.”

I was at a loss. As luck would have it, Mama Rosa, the wise midwife, was standing in the doorway behind me and could explain. Their society was matrilineal and one outcome of this was that the mother’s family—usually the mother’s brother—was considered responsible for the child. At that point, I found it hard to grasp the strength of this social structure.

“But he has many uncles and I know they will give him blood,” the father said.

I freaked out. “Come on, can’t I test your blood all the same?”

Mama Rosa explained that arguing was pointless. The father would never accept donating blood to his son. In his eyes, his son belonged to another family, and it was unhealthy to pass blood on to another family. I capitulated.

The father hurried out into the rain. It did not take long before he and two sweating, soaked uncles came running back. One uncle’s blood group matched his nephew’s. Ten minutes after the transfusion, the child’s respiration calmed down and he began to cough. Just a few hours later, the fever started coming down.

Much of what I did at the hospital in Mozambique was actually public health oriented. Ward rounds can be enormously powerful if you talk to the patients in a way that will make them broadcast your ideas when they go back to their villages. In many parts of the world, going to see the doctor provides conversation fodder for weeks.

To me, it had become a matter of my identity: what was I here for? To cure just the patient in front of me, or to improve the health of the whole community?

I decided it was time to work out the right approach by analyzing the matter numerically. I would collect data in an interview-based investigation. To make it manageable, I decided to focus on the number of children who died in Nacala city and exclude its rural hinterland. This was because there were three health centers in the city itself and, even if most of the population lived in very meager conditions, most of them could get to one of the centers and be referred to the hospital, or else go straight to the hospital emergency unit if a child was suddenly taken very ill.

That evening spent discussing ethics with my colleague from the regional hospital in Nampula had made me feel this investigation was imperative. I had some rough approximations, using already existing information. The 1980 census showed that Nacala had 85,000 inhabitants and that some 3,000 babies were born every year. A total of 946 children had been hospitalized during the past year and of those, fifty-two had died, despite receiving the best care we could offer them. Almost all of the children admitted to hospital were under five years old.

My next question was how many children under five years of age were dying at home, never making it to hospital? The under-five child-mortality figure for the whole country was 26 percent. The latest census gave us the number of births in the city, roughly 3,000 per year, yet the population of the district was five times that of the city, so we estimated there had probably been five times as many births: 15,000. Twenty-six percent of that number gave us 3,900: the number of child deaths I was responsible for trying to prevent. Despite the fact that one child died every week in the hospital, it was a fraction of the total: I was seeing only 1.3 percent of the children I needed to help.

Talking to the hospital staff, I learned that many children were not brought to the hospital when they fell ill. The main reason was apparently that the families consulted “traditional doctors,” who were available round the clock. The alternatives were either one of the town’s health centers, open only during the working week, or an emergency hospital admission.

I planned the investigation together with Agneta, who was working locally as a midwife and was also in charge of the childhood vaccination program that we offered regularly in different areas of the town. By then, our friend and colleague Anders Molin was around to share the work with us. Anders had trained in Sweden and been placed in Nacala. Now the town had two doctors, which made a huge difference to us. Anders shared our quarters and became yet another titular uncle for our children. To me, his presence meant an invaluable lightening of my workload.

Our very limited resources meant that the plan had to be very simple. We chose an area of Nacala called Matapuhe, which, according to the census, had a population of 3,700. Next, we arranged meetings with the community leaders and asked for their help in organizing the study.

In the summer of 1981, a group of seven interviewers, all members of our healthcare team, met local women of child-bearing age. The important numbers we wanted were the total number of births and child deaths over the previous twelve months. Most of the women had no schooling at all and did not count time in calendar months, so we used another way of establishing dates: we did the interviews in the holy month of Ramadan, allowing the mothers to recall what had happened in the twelve months since the last Ramadan. We were careful of our manners and how we expressed ourselves when we asked these delicate questions.

It went quickly and well, perhaps especially because, at the same time, we ran a small treatment unit for ordinary health problems and also offered vaccinations for the children. The ready availability of healthcare encouraged participation and attendance. Once I had the data, I extrapolated for the whole town on the assumption that Matapuhe was a relatively representative area.

The outcomes were very clear-cut, beyond any doubts or fuzziness. In one year in Nacala town fifty-two children had died in the hospital and 672 at home: more than ten times as many. An arguably even more important observation was that, of those who died at home, about half had not been taken to any care facility in their last week of life. In other words, we had shown a need to organize, support, and supervise local clinics where the staff could manage diarrhea, pneumonia, and malaria before the children became terminally ill. It would save many more lives than giving intravenous fluids to dying children in the hospital.

Hans in Nacala with colleague Anders Molin

The child mortality rate in the town turned out to be about 20 percent, not the 10 percent I had originally estimated. We expected it to be higher in the countryside where three-quarters of the region’s population lived. I should be trying to prevent more than three thousand child deaths each year, of which only fifty-two were happening in the hospital. It would have been seriously unethical to spend more resources on the hospital before the majority of the population could access some basic form of healthcare.

“Basic healthcare for all” had been a World Health Organization policy since 1978 and the WHO had for decades been prioritizing vaccinations and basic-care facilities for as many children as possible in as many countries as possible. I was lucky to be working in Mozambique, a country that had begun to implement these policies immediately after gaining independence. During my years in Mozambique, many villages were invited to send a representative to the city for a brief period of education. The focus was on creating small healthcare units in all areas, within walking distance for mothers with babies and very young children. They would offer vaccinations and treatments for the main diseases that killed young children.

Were we right to take our lead from the terrible facts of child mortality, rather than to be guided by what was thought to be ethically correct when managing hospital care? Yes. When I was working in Mozambique, child mortality was estimated to be at around 26 percent and, now, thirty-five years later, it is down to 8 percent. It took sixty years in Sweden, from 1860 to 1920, to reduce child mortality from 26 to 8 percent.

During those thirty-five years, Mozambique endured a decade of bloody civil war and coped with a very serious epidemic of HIV. Despite this, its child mortality fell almost twice as fast as Sweden’s had almost one hundred years earlier. This also holds true if you compare Europe and Africa overall. Africa is catching up with Europe in matters related to child health, and it is due to accepting evidence-based policies and investment targets.

It can be difficult to persuade oneself to prioritize thinking rather than feeling, but it can be done through careful tallying and thinking clearly about the data.

There was one thing that I still had not grasped through looking at the numbers, though: the true depth of extreme poverty. I understood this first when prompted by the most powerful of feelings—fear.

A whole series of tragic and dramatic events took place during our life in Nacala but we also experienced many good things together. Anders Molin’s arrival meant that I could relax when he was on duty and I enjoyed wonderful family Sundays on the beach. As I was no longer on call every night, I could also spend some evenings with the children and sleep soundly at night.

We did the hardest work of our lives in Nacala, but, in the middle of all that, we were a happy family. We grew papaya and kept ducks in the garden, a dry-as-dust patch of sandy soil. Despite the challenges, our health was fine. One magic night, Agneta hugged me and whispered in my ear: “I want another baby.” To us, the children were our source of joy and meaning in life. It was how we wanted it to be for many years to come. To me, Agneta’s wish sprung from love but also from a shared vision of life beyond my cancer.

She became pregnant faster than we ever imagined and at first her pregnancy progressed well. Together, we followed the growth of her belly by measuring it every Saturday, the day a midwife came to make her own checks. Then, one Saturday toward the end of 1980, we realized that there had been no growth during the past week. There was no change the following week either. We had to take this warning seriously.

During the next week, we had to make a critical decision: would we risk a delivery in Mozambique? No.

In January 1981, Agneta and the children boarded the plane from Maputo to Sweden and I returned alone to Nacala. Our plan was that a month later, just after the birth, I would fly back to be with them.

The day after Agneta and the children had left, there was an outbreak of cholera in our hospital’s catchment area. Cholera is fast-moving. Once the diarrhea has set in, a patient can die within a few hours. I immediately gathered a team of three health staff with the necessary equipment and left Nacala. As I had been taught to do, we settled temporarily in the center of the outbreak. Our basic intensive care unit stayed in place for two weeks to do battle with the epidemic in the most distant villages.

One evening, I was stopped on the road by a man who was carrying his unconscious son. The boy was a cholera victim, his sister had already died of the disease and their father knew that he probably would soon lose his second child. At some point after the boy’s diarrhea had begun, his father had heard the distant engine sound of our car. He was sure we would come back by the same road and, even though their home was far up in the hills, he had set out for the road, carrying his boy on his back. When he put the child down on the ground, I saw by the glow of the headlights how quickly the sand became wet. The child was losing far too much fluid and must be taken to the unit quickly.

We did not want the cholera infection to soak into the car seat and put him on the floor of the car instead. He was unconscious, his pulse was too faint to detect and there was no chance of making him drink. He was half an hour from death.

The father was completely calm and collected, and entirely focused on his child. Knowing that we had cured other people with cholera, and that his son’s fading life depended on me, he was helpful and intensely alert.

It was dark when we arrived at our base unit. We parked the car but kept the headlights on. I asked the driver to shut down the engine so I could hear the boy’s breathing. The darkness and silence were broken only by the noise of his breathing and the nighttime sounds of the forest around us—mostly from frogs and geckoes. The father sat still, the nurse stood behind me. Everyone was silent.

I searched for a pulse somewhere. Was he dead already?

Finally, I picked up a faint arterial beat in the groin. I had to get a needle into the big vein lying next to the artery. I sensed the small snap of the needle piercing the wall of the vein. With the needle in place, I could then hook the boy up to an intravenous drip. We had fluid-replacement bags and flow monitors—small chambers showing the flow rate for the drip. The flow began. I crouched in front of the boy with my fingers on his pulse, staring at the monitor, and asked the nurse to let the fluid go in at top speed.

“Hold his legs still,” I instructed the father.

He took his son’s legs in an iron grip to stop him from moving and damaging the vessel with the needle in it. My body was going stiff from crouching. We were very quiet. The fluid flowed and flowed.

Minutes passed. Five minutes. Ten. Nothing happened. Eleven. Twelve. The boy’s eyelids twitched, his eyes opened. He lifted his head. He was waking up.