6

From the Lecture Theater to Davos

The decisive reactions to my bubble graph were neither those of the Karolinska Institute professors nor those of my students. The responses which had by far the biggest influence on my future professional life came from my son, Ola, and perhaps even more so, from his wife, Anna.

Ola and Anna, both twenty-three years old, had come for supper one evening in September 1998. They lived in Gothenburg at the time but were visiting Uppsala for the weekend. Anna had completed a course in cultural sociology and was now studying at the School of Photography at the university. Ola was studying economic history but his plan was simply to accumulate enough university exam passes to qualify for grants. He wanted to use the money to buy paint and, with his new portfolio, apply for a place at the College of Art, where he had already been short-listed for two years running.

We were about to start on the dessert when I showed them my new, excitingly colorful bubble graph. Instantly, I caught their attention. They were even more curious when I outlined the fact-resistant attitudes of my students who refused to accept that the countries of the world were scattered along a continuous line, from poverty to wealth. Anna asked for a copy to take back to Gothenburg. She displayed it on the wall in their apartment, where their friends would easily see it. At the time, I had no notion that this would be the start of a lifelong collaboration with Anna and Ola, marrying together my obsession with numbers and their artistic talents. You never know where supper with the family might take you.

A couple of weeks later, on September 16, 1998, I received an email from Ola with the subject line: “Ola tries something new.” Ola recounted enthusiastically how he had joined an instructive session in a magazine production workshop, run by the Gothenburg Cultural Center, and had heard about a new computer animation program. He ended the email with: “And this is the good news. In the next two months, I plan to use the animation program Director 6.0 and make your graph of Child Mortality v. GNP come alive. If you’d like me to, that is? Please let me know.” My boring reply was: “Sounds great, go ahead.” I had not the slightest clue what Ola was on about.

A few more weeks had passed when Ola phoned to tell me that he could make the bubbles move but to work on it he needed a more powerful home computer. He wanted to follow up his idea of tweaking the digital version of the graph to make the country bubbles move from one year to the next. The user could then see how and where the world was changing with time. He asked me nicely if I would lend him the money for a new computer. His computer had been a gift from me twelve years ago.

So, what did I say? Just a few years later I would be lauded for showing off the very program that Ola and Anna went on to build for me. At the time, I suspected that Ola wanted the computer to make an animated cartoon to add to his art portfolio. He had already studied at a few different colleges, taken a handful of courses and then worked with a theater in Stockholm. “He had better get used to being short of money if he plans to make a living as an artist,” I said to myself, my mind clouded by dull parental thoughts. “No, Ola. I’ve already given you my old computer,” I told him. “Surely that will do.” Ola tried to explain that creating moving images required something more sophisticated but I didn’t really listen.

The following day, Ola phoned again to tell me that a bank had agreed to lend him the money but they wanted the signature of a guarantor. I still did not listen properly and blocked off his enthusiasm and persistence. Once more, my reply was “No.”

It still pains me to confess my behavior. The sum he wanted wouldn’t have been a big drain on the family coffers. I was showing a complete inability to hear what Ola was really saying. Still, he did not give up and bought a computer on credit, from a friend. Then he managed to get himself a key to the Cultural Center’s magazine workshop, where he taught himself programming at night during the autumn of 1998. There he wrote the code for the first animated graph of what he called the “Historical World Health Chart.” Anna designed the links. They showed it to me when they were staying with us that Christmas. I remember catching my breath and my eyes widening as the bubbles slowly, smoothly moved from illness and poverty in the lower left-hand corner of the graph, and up toward wealth and longevity in the upper right-hand corner.

“And, look at this—you can track a country! I’ll do Sweden for you,” Ola said, and smiled. The bubbles moved from 1820 to 1997 again for all the countries, but this time Sweden left a trail of bubble markers, one every five years. It was a small innovation but it enabled us to follow the course of Sweden’s path through the last two centuries and compare it with the development of other countries. As the cursor stopped on a bubble, you saw the name of the country and, when the cursor followed the Swedish trail, it showed the year Sweden had reached this or that level of public health or average income.

Wow!

“We must apply for money to develop this idea even further!” I exclaimed spontaneously.

But it turned out to be extremely difficult to get any funding from the sources that would usually give me research grants. As the funding delay continued, Agneta decided to lend Anna and Ola enough for a computer each so that they could work from home, and I began to use the animated bubble graph in my lectures.

Previously, I had been invited to speak only as far afield as Copenhagen. My new tool kit changed this. Out of the blue, I heard from Geneva. The head of statistics at the WHO wanted me to give a talk and later commented: “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Then Sida—Sweden’s state aid organization—decided to support our peculiar project. Anna and Ola gave up their studies and employed skilled coders to work on new visualizations of the data set. Dollar Street, Anna’s idea, was one of these programs.

These applications elevated my lectures to new levels and made it much easier for me to complete what I saw as my vocation: raising awareness among university students and aid workers as to what was really happening in global development. That was why I held out against a request from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to appear on the so-called International Square at that year’s book fair in Gothenburg.

Why would I hire myself out to chat about world development to the public at large? I had only ever given talks to academic audiences. Besides, I was skeptical about private enterprise: even the book fair seemed too commercial for my liking. The foreign affairs people had to nag me to attend, but finally I caved in and went to Gothenburg.

The hall housing the International Square was large enough for all conceivable aid organizations and international charities to set out their stalls. In front of the speakers’ stage, twenty chairs had been arranged for the audience, yet people moving around on the “square” were unable to see the screen on which I projected my imagery. I disapproved of this and twisted the screen to face outward. It meant that my audience had to stand to see but, because the screen could now be seen from the walkway connecting the hall to the rest of the fair, my audience was now almost a hundred rather than just twenty people.

On that day in September 2003, a man called Bo Ekman stopped to listen to my talk. When I had finished speaking, people queued to talk to me and Ekman waited his turn.

“Heads of industry should hear you speak,” he said. “What I heard was awfully good.”

He surprised me. Bo Ekman, a conventional-looking man in an unremarkable suit, was a major name in Swedish industry. He certainly did not fit easily into the group of a hundred-odd people who had listened to me. He looked ordinary but everything he said was interesting.

Bo asked me to come and speak at the next AGM of Tällberg, a foundation he had started twenty years earlier. The annual meeting was a kind of forum where politicians, academics, and industrialists met and discussed the great issues of the future. I was curious and accepted his invitation.

I suddenly had a completely new audience, including the bosses of Sweden’s biggest industries, men and women I had only read about in the newspapers. After my account of the world, they approached me with very insightful questions. That meeting at Tällberg was the start of a fascinating journey.

I was surprised and dismayed to find that the executives of the very largest companies were very well-informed about how the world was changing, much more so than my committed, internationally minded students and aid-organization staff. These business executives needed a grip on facts or their firms would collapse. They had to keep track.

Many public-health experts are deeply suspicious of private enterprise, believing it is all about flogging tobacco and alcohol products or fast cars. After giving so many lectures to staff in private-sector organizations, I acquired a respect for commerce that I had previously lacked because of my working-class background.

We received more and more invitations to demonstrate our new, fact-based representations of the world. We were asked to speak at conferences all over the world and also had a terrific number of requests for computer-based images of other statistical data sets. Almost all the organizations contacting us had built large databases only to find it hard to convey the meaning of their data—they ranged from UNESCO, the World Bank, and UNICEF to the Swedish local authorities and Rio de Janeiro’s town planners.

If we had been capitalists at heart, we would surely have jumped at the chance to sign contracts with all these interested parties but, as Anna concisely expressed it, our vision of liberating this data was too huge for us to manage on our own. We agreed that the best thing would be if Google were to steal our ideas, because they did not charge users for their services.

In 2006, barely three years after my first presentation to the heads of Swedish industries, I was invited to give my first TED Talk. Anna and Ola had actually been invited a year earlier to what was at the time a secret conference for handpicked delegates and which had not yet put a single video on YouTube. But the TED Talk people refused on principle to pay airfares, trying instead to persuade Anna and Ola what a huge honor it was to be invited at all. To which they had replied: “Sorry, but we can’t afford the flights.”

Before my first TED presentation, I phoned Anna and Ola to discuss the content.

“What about sword swallowing?” I asked, referring to a party trick of mine.

“No, don’t do that,” Ola advised. “Run the chimp test and then show them the visuals.”

It was an incredible success. I was even on the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle.

The following year I was invited to talk at TED again and, true to habit, I phoned Anna and Ola to ask their advice: “What have I got to show them now?”

“Nothing new, so you had better swallow a sword or two,” Ola said.

The actor Meg Ryan had a front-row seat. She cheered loudly and jumped up and down when I pulled the sword from my throat and bowed to the audience. I still regard Meg Ryan’s cheering as one of my greatest triumphs.

An unassuming-looking man with a long fringe was hovering quietly among the many people who wanted to speak to me after the talk. He turned out to be Larry Page, one of the founders of Google. Unlike most of the other attendees, he had realized right away that I was unlikely to have written the code for my bubble graphs myself. I told him about Anna and Ola, who were promptly invited to Google headquarters along with the programmers working with them at Gapminder, the not-for-profit foundation we had founded. Once installed at Google, they would be able to turn Anna’s vision of democratic access to official statistics into reality. The Gapminder Foundation sold the moving-bubble source code to Google and for three years, Anna and Ola worked in the company’s Silicon Valley building. Their goal was to create and shape Google Public Data, an application that makes it much easier to find and display statistics.

The proceeds of the sale meant that I finally dared to leave academia. In 2007, I severed almost all links with scientific research, keeping just 10 percent of my post at the Karolinska Institute and devoting 90 percent of my working time to Gapminder. My title there was “edutainer.” I employed a new team and we started to put short films up on YouTube.

Over the years that followed, my office was flooded with invitations to lecture all over the world. The pressure was such that I had to engage an assistant. I was constantly asked to speak at conferences, of which some were recurring events and others were one-offs. The latter included a US State Department get-together in Washington DC, where I addressed the foreign affairs specialists with a talk I called “Let my data set change your mindset.”

With the founders of Google

One day, an email arrived from Melinda Gates: would I attend a conference in New York focusing on the United Nations’ developmental goals and especially on child mortality. I agreed, of course.

When you are asked to give a talk, you must first make sure you are clear about one thing: what precisely is my subject? Next, you must work out how to illustrate it and what is the best way to display the material. What do I want my audience to remember? I left for New York without having made up my mind about any of this.

My assistant and I arrived, as planned, a day early. I like being in place in good time and to then prepare thoroughly up to the very last minute—it helps me to memorize what I want to say. I always want access to the space to get an idea of the layout and familiarize myself with things like where my laptop will go and where the cable should run. These technical details matter very much to me. Many speakers cannot be bothered and leave their slides in the hands of someone else. I never do. The timing is much better if you are responsible for pressing the button. It gives your talk the pace it needs.

The night before the conference began, I had been invited to a dinner in a restaurant in lower Manhattan, south of UN headquarters.

I was a little uncertain about what to wear. I knew that Graça Machel would be present. She had been the minister of education in Mozambique during the years Agneta and I were there. At the time, she had been married to the president of Mozambique. These days, she was married to Nelson Mandela. Melinda Gates would also be at the dinner.

I chose a jacket but no tie. In my bag, I carried something very precious to me: my daughter Anna’s school notepad, carrying the logo of the Mozambican Ministry of Education. My arrival at the restaurant was overwhelming: I had been seated in a central position, next to Graça Machel, with Melinda Gates facing me.

The conversation that evening was quiet but profound and witty, especially the exchanges between Melinda and Graça. They discussed all the great issues of international development. I joined in now and then but mostly listened as these two giants of world policy talked about girls’ rights to education, access to contraception, distribution of vaccines in rural areas, the furthering of democratic governance, and whether social development must be achieved before political change is possible—and, in every context, what the UN could do and what the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation could do. I was fascinated by the way they talked. They were obviously close friends, almost like sisters. Having met so often, and sharing the same values, they knew each other’s projects in detail.

Both were deeply concerned about the issues surrounding access to contraception. Melinda felt that the matter should be seen not in terms of human rights but as an intervention in support of family life—for one thing, people grasp that family life will be easier if the children are not born too close together. Graça saw the question from a South African perspective: there, arguing in favor of using contraception was less controversial than in Mozambique, which had experienced extreme poverty so recently. For me, it was a privilege to listen as people with the capacity to make a difference in the world peacefully discuss what best to do next.

Every now and again the two women asked me questions. Among other things, I told them about how to measure child mortality. I described how you had to select a representative female population from the country in question and then arrange for qualified interviewers to ask them about their lives. The questions were probing: for example, how had life been for them during the last few years, had they lost children and, if so, how. This approach enabled us to investigate child mortality in depth.

Graça and Melinda listened attentively and asked me about some critical issues. I told them there was no doubt that most African countries were developing in the right direction because the evidence was there in the form of decreasing child mortality.

Toward the end of the evening, when I felt that we had been getting on very well, I decided it was now or never.

“I would like to show you something. And to thank you,” I said to Graça. Melinda peered over the table to see what I had in my hand. I pulled out Anna’s school notebook. I spoke about our time in Mozambique from 1979 to 1981 and explained that our daughter had been to school there. Graça Machel’s eyes grew wide. “Did you meet my husband?”

“No, but I heard a speech he gave in Nampula,” I said.

The notebook caused quite a stir. Everyone wanted to have a look.

“It was the education minister who saw to it that my daughter went to school,” I said, while the notebook was handed around the table.

As I walked back through Manhattan that evening I made little elated leaps. Talking with these two women had given me such a high.

The dinner stayed with me as the greatest memory of the trip. It had humbled me. My preconceived notion had been that people in high places were shallow and egotistical. I had thought ill of them, in general, and expected arrogance. Instead, I had met wise, thoughtful and kind individuals.

That dinner conversation also taught me how important personal contacts always are, even at the most elevated social levels. It was an insight that was strengthened every time I attended the World Economic Forum in Davos, an annual event where the power brokers of the world meet to discuss the big issues of the future. It has grown into the world’s largest assembly of people who hold power—those active in industry, economics, and finance as well as politicians, heads of state, representatives of international organizations including the UN and organizations such as Amnesty, leading media figures, and academic experts in global issues.

Davos is an ordinary-looking Alpine town with a modest railway station. It had snowed that morning and as Agneta and I pulled our wheeled suitcases along I slipped and slithered on the steep, icy street.

Before long, I found myself seated in a small meeting room, listening to a minister for the environment from an EU country. He was in an accusatory mood:

“The bulk of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions come from China, India, and the other developing economies, and projections show they are rising at a rate that will cause very dangerous climate change. China already releases more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than the USA, and India releases more than Germany.”

The minister was a member of the group of politicians and industrialists discussing climate change at Davos in January 2007. His statement about the CO2 emissions from China and India was made in a neutral, unemotional tone, as if his view was purely factual. I scanned the small meeting room: Europeans and Americans were seated along one side of the table while delegates from the rest of the world, including India and China with their rapidly growing economies, were lined up along the other side. The Chinese civil servant kept staring straight ahead but his shoulders were drawn up and his neck seemed somehow locked as he listened to what the EU minister had to say. His Indian counterpart was leaning forward and waving to catch the moderator’s attention.

When the Indian minister was called upon to speak, he stood calmly for a moment. He wore an elegant navy-blue turban and a dark gray suit. In silence, he looked around the table at each of the other countries’ representatives, gazing at the CEO of one of the largest oil companies for a little longer than the rest. As one of India’s most senior civil servants, he had many years of experience as an expert advisor to the World Bank and the IMF. After his brief but effective silence, he made a sweeping gesture toward the “wealthy” side of the table.

“We are in a delicate situation. That we are here at all is the fault of your countries, the wealthiest in the world! You fired your economies with coal and have been burning oil for centuries. Your activities—no one else’s—have brought us all to the brink of a major climate crisis,” he said loudly and aggressively, breaking all diplomatic codes.

Then his body language changed abruptly. He pressed the palms of his hands together in front of his chest in an Indian greeting, bowing to the shocked delegates from the West.

“But we forgive you because you did not know what you were doing.”

The words were spoken in a near-whisper. The audience was silent. There was a giggle from somewhere in the back. A few people exchanged anxious smiles.

The Indian minister straightened up again, stared at his opponents and wagged his finger at them.

“From today, we will base our calculations on CO2 emissions per capita.”

I was so impressed by the sharpness of his analysis that I can’t remember the reactions of others in the room. Over the years, I had become horrified at the way blame for causing climate change had been systematically heaped on India and China. The basis has been their total emissions, even though both countries have much larger populations than other countries. I had always thought it was a silly argument, analogous to stating that obesity was a more serious issue in China than in the USA because China’s total body mass was the bigger of the two. Given the huge differences in population size, it is pointless to speak of “total emissions per country.” Sweden, with ten million inhabitants, could by that logic get away with vastly increased CO2 emissions per capita because there are so few of us.

What the Indian civil servant expressed in public was something that had worried me for years. Is this really how they think, the men and women in power? But the way he said it made me hope that the restructuring of the world was on its way.

It is interesting to give lectures for company staff and focus on what they feel really matters. Sometimes I use links to my own past—for instance, to my grandma, who washed clothes in a laundry tub in a cement trough while dreaming of a washing machine.

I had been invited to give a talk to the management of a well-known white goods company. The CEO wanted me to demonstrate the world’s demographic and economic development and go on to explore the worldwide need for cookers, fridges, and washing machines.

I began with a simple display of how income distribution related to population health, pointing out that people become healthier first and that economic growth follows later. This progress means that today we can make qualified guesses about where development might take off, given a sufficiently good economic policy.

“Asia will be the next enormous marketplace. Latin America and the Middle East as well, but Africa will follow later. For you, expansion in Asia is what matters just now.”

Someone asked, “What do they want there, would you say?”

“You make electric cookers, mostly, but often gas is the cheaper fuel in poorer countries. A fridge is probably what households will invest in first; they’re much valued, especially in warm climates. But your firm makes expensive goods and people with lower incomes need cheaper things. I don’t know what you feel about that.

“Have you talked to your own relatives?” I went on. “Have you ever asked the oldest woman in the family how she felt when the washing machine was installed?”

I pointed at 1952 on the graph displayed behind me. “Here is when Swedish families got their first washing machines. We were then at the stage China is at today. Imagine the market—1.3 billion people.”

A washing machine is a product that many people in the world would love to own. Imagine that! If you could make washing-machine ownership match mobile-phone ownership, which has spread worldwide.

“What is lacking is a technological breakthrough. The old types of washing machine use too much water, and that will not sell in densely populated Asian countries. Add to this the problem of using detergents and other chemicals, and don’t forget the demands on the electricity supply.”

They listened. “How will you deal with these problems?” I asked. “Can you think up something as smart as the mobile phone? Once you do, you can access billions of customers. This isn’t about ‘corporate social responsibility’; it’s about your future profits! Unless you get on with redesigning your product, you will lose the leading position in the marketplace.”

The arguments inside the corporation became clear: opposing sides wanted either to hang on to old market shares in the West or try out simpler models and gain more customers in new markets. I have rarely seen so distinctly the difference facts can make.

I had spoken to them using the same facts as I had shown to the UN and aid organizations. But I presented them from the producers’ point of view. I had just scratched the surface of their outdated view of the world.

In 2011, when our children had grown up and moved out and three decades had passed since we had lived in Mozambique, we decided to return. After flying from Maputo we rented a car in Nampula and drove toward Nacala. On the way, we passed the place where I had almost died in a car accident. We stopped and stared. It looked just the same: grass and mud. But, as soon as we entered the outskirts of Nacala, we started noticing changes. The town had expanded into the countryside with large industrial sites surrounded by nicely painted walls. A truck swung out onto the road in front of us. It was loaded to the top with colorful, patterned foam-rubber mattresses wrapped in transparent plastic. Ah, at last, I thought. At last people can make love on something soft rather that hard-trodden dirt floors. At last, modernization. That truck seemed symbolic. The port of Nacala had grown to be the industrial city we had hoped it would become. But the really amazing moment for us was returning to the hospital.

We parked on the sloping road leading down into the center. We recognized all the hospital buildings, except one: it was tiny and looked like a small kiosk. The door was covered in posters. One of them showed a man hitting a woman, with a cross through the scene. The door stood open and we peeped inside. We saw a man busy entering things on paper, seated at a dark wooden desk. A fragile-looking, plainly dressed woman of about twenty-five was standing in front of him, wearing flip-flops. Her eyes were frightened.

“Please excuse us. We’re disturbing you,” we said cautiously.

“Not at all, don’t worry,” the nurse said. Then he turned to the woman and asked her if she minded if he chatted to us for a while.

We introduced ourselves, explaining that we had worked in the hospital thirty years ago. The nurse, who was probably not yet thirty, said he had heard that foreign doctors had worked there once upon a time. His job, he told us, was to look after the rights of women.

“I help women to take crimes against them to court. I take care of inheritance claims as well, and prepare statements to be given to the police,” he said.

We were utterly taken aback. When we had worked in Nacala the level of violence toward women had been grotesque. It is often the case in extremely poor communities, and no one had seemed ready to change it. Now, with basic healthcare being provided, the system had moved on to attacking gender-based crime and defending women’s rights. The nurse gave us a small information brochure.

The old building that had housed the outpatient clinic in our time still performed the same function but had now been improved with a veranda running along the front. The shade was a good idea. At one end was a smaller building for the expanding dental service.

The district where I had worked in 1980 had at that time never been served by more than two doctors. Now it was looked after by sixteen medically qualified people and a new hospital had been built. The hospital manager was the most clinically experienced of the doctors working there, a highly qualified and competent Mozambican gynecologist.

In the reception area, we told a nurse that we had worked in the hospital thirty years ago. We showed her a photo of the staff from 1980 and soon a small cluster of people formed around us to have a look. They recognized people, laughing delightedly and commenting on who had died and who had been good-looking in their youth. And to our enormous surprise and delight one of the nurses recognized one of our old assistant nurses, Mama Rosa, and called her on her mobile phone. That was how we later were able to meet some of our old co-workers and share a lunch together.

A nurse showed us round the antenatal clinic linked to the childcare center, where twenty proudly expectant women were sitting in the waiting room. All were nicely dressed. It is what pregnancy feels like in Africa—you are proud and pleased to be pregnant and to attend the social event that is a visit to the antenatal clinic.

What had been the outpatient reception in our time was now a specialized area for patients with HIV and AIDS. It was staffed by two nurses and a doctor. The doctor wore a crisp white coat and was seated at a glass-topped desk. When he heard that his post had been mine thirty years ago, we hugged.

That doctor was now responsible for primary care in the town. He gave me an overview of the pattern of disease. I listened in silence. Later, Agneta pointed out it was ages since I had shut up for an entire half hour.

He had given us a comprehensive understanding of how disease was distributed in his district. They still had problems with childhood infections, and the widespread availability of mosquito nets had not eliminated malaria cases. And, of course, there was pneumonia and diarrhea as well as victims of traffic accidents and other minor and major injuries.

“I assume it was just the same when you were here,” he said.

Agneta asked about the child and adolescent psychiatry services. Did they see much ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder)?

“Yes, we do. It’s tragic. We see them coming in for minor surgery.” The doctor sighed.

He told us that the new medicines for treating ADHD were too expensive, and psychologists seemed unable to help these children. Their diagnosis meant that they got into trouble—climbing on buildings and trees, hurting themselves falling off, or being beaten up. And then they came in to have wounds stitched.

The thoughtful doctor went on to tell us that he did not work shifts in the hospital as I had done. Also, another doctor was responsible for the rural catchment area. In the 1970s, that had been just another part of my job. His post carried about a third of the workload that mine had but, even so, his load was heavy. He also mentioned that he had hoped to buy a house on the coast but had been too late. The property prices had already risen so much that he could not afford to buy a site with a sea view.

As we left, I was full of admiration and deep respect.

The new hospital had been built a little farther away, high up above the town, on a spacious site with room for expansion. There was an ambulance driveway to an emergency entrance. The morning routine was like that of a Swedish hospital: before the visit to the wards, the day began with an X-ray session and a brief review of the emergency patients from the night.

Because of the infection risk, you were allowed to put your rucksack only on a chair and not on the floor. The delivery suite had a tiled floor that could be washed and to avoid dirt being brought in, the staff wore indoor shoes. These days, dehydrated children in Nacala were put on intravenous drips, just as my pediatrician friend had insisted should be the case thirty years earlier.

This Mozambique was not like the country we had lived in. This is not to say that everything was perfect—far from it. But everything had moved forward.

There were still extremely poor areas to the north of Nacala, where two junior medics worked alone, serving a large population. The size of their task became clear when we heard of the thirteen-year-old girl who had become pregnant. When she was about to give birth, the girl, whose pelvis was too narrow for childbirth, had become extremely ill. She had been transported to the hospital from her remote part of the district—a northern area from where, in my days, we saw no patients at all. On the way to Nacala, the crisis point was reached and her uterus burst. She not only lost the baby but had to have her torn uterus surgically removed, meaning she would never be able to have children. Agneta and I knew only too well what it means when a very young girl begins a home delivery and her body gives up. The message was clear: in some parts of the district, the poverty was no better than in our time, but here, in town, things had improved.

The staff was exceedingly curious and keen to talk with me. They were very aware that some aspects of the health service were still insufficient and hoped I would want to stay. Lack of specialization was one obstacle to continued development. There was a role for me, I felt—in my thirties, I had been the doctor who tried to learn from the nurses, but now, in my sixties, I could be useful by training specialists. The young doctors had been to medical school in the capital and had their degrees, but lacked the specialist skills you acquire during the years as a junior doctor under the guidance of senior and experienced specialists.

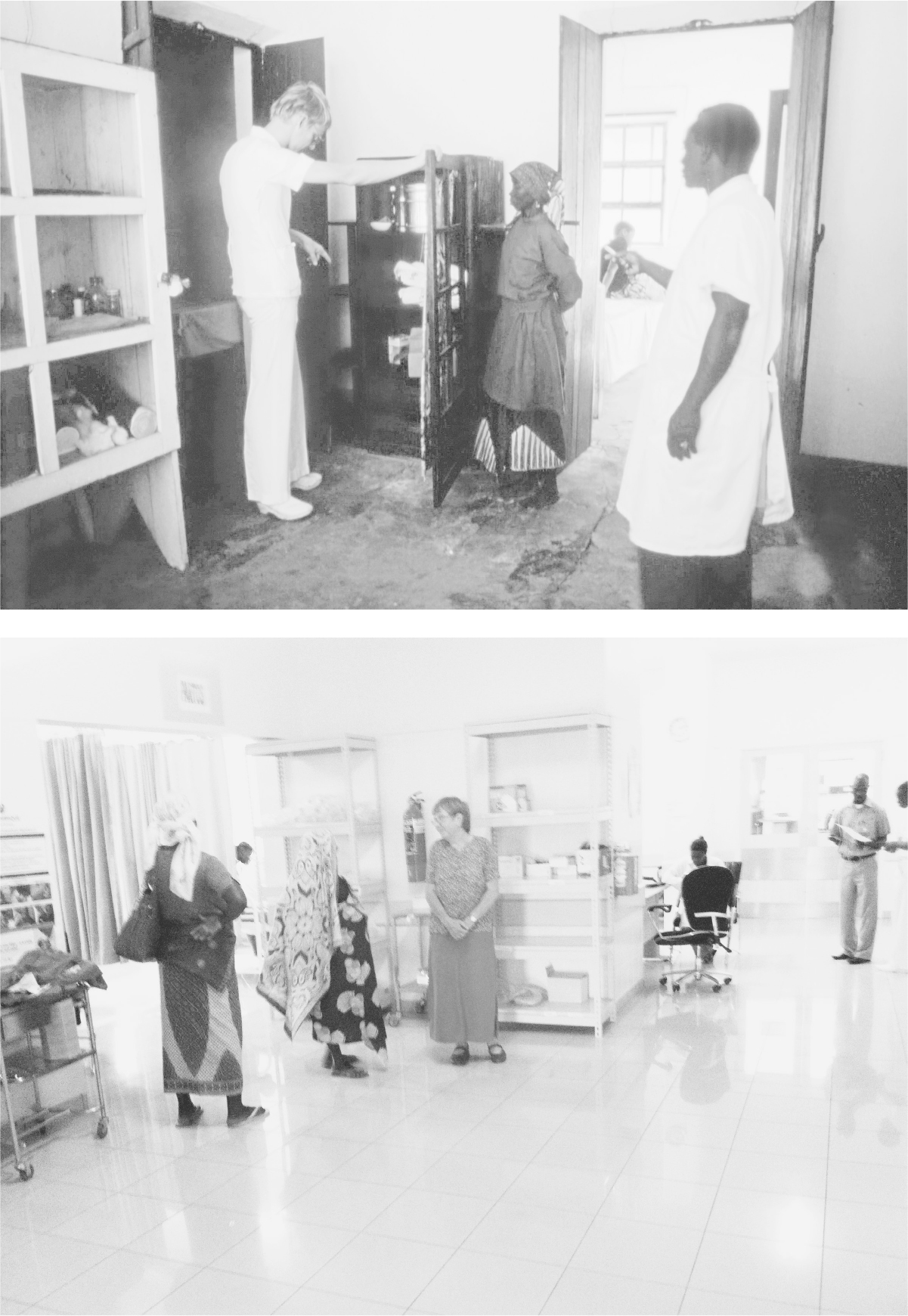

At my desk, then and now

The clinic, then and now

During my two years in Nacala in the late 1970s, I never diagnosed a case of type 1 diabetes. The patients all died before they saw a doctor. Now, the medics were having to learn to cope with such previously unseen diseases. During the ward round that evening, we witnessed the changing times in the shape of a twenty-one-year-old woman.

She was extremely thin, as anyone is with advanced, untreated diabetes. Her entire body language expressed alarm. As the ward-round staff stood talking to one another, she seemed to expect them to turn to her and tell her she would die.

Diabetes begins with frequent peeing and weight loss, followed by hyperventilation, loss of consciousness, and then death, unless insulin is given in time. The progression can be fast, sometimes as short as one week.

I tried to say something soothing, as one does when standing by a hospital bed. The Mozambican doctors stood to my left and right and I told them about her condition, as I myself had once been taught about treating diabetics by more experienced medics at Hudiksvall hospital back in 1975.

We spent that whole week in and around Nacala. It was moving to see again the colleagues from the two most intensive years of clinical practice of our lives. We noted the growth of the local economy but also the huge challenges that still remained.

Mama Rosa, the assistant nurse from the maternity ward thirty years ago, arranged a lunch for us at a restaurant close to the marketplace. Papa Enrique, to whom I had once given my spare spectacles, was now almost blind and needed help with his food. His grandson had brought him on his motorbike. It was unclear whether Enrique recalled anything of his past life and it was difficult to talk with him as his hearing was not the best, but we did all we could to try to explain who we were. Seeing them all again made me almost tearful.

And now, at last, I had a chance to apologize to Ahmed.

Ahmed had been our hospital cleaner. I used to walk round inspecting the whole hospital, even the toilets. I lost my temper if anything looked dirty. Everywhere had to be clean.

One morning, the toilets were filthy, not even flushed properly. I was outraged and shouted: “Where is Ahmed?”

“He isn’t in yet,” someone said.

“What, not in yet? It’s quarter to nine already!”

“We don’t know what’s happened.”

“Can’t someone go and fetch him?”

“But maybe we should just wait—”

I interrupted, speaking more loudly: “Someone should go and get him here, now.”

An hour later, Ahmed stood outside my door, shaking.

“Senhor Doktor, I am very sorry that I’m late. My son died last night.”

My expression did not change. “Is that so? What did he die from?”

“Measles.”

“Why didn’t you see that he was vaccinated?”

Ahmed’s first-born son had died. His home had been taken over by the wake but there I was, telling him off for being late and then for not having had his child vaccinated. It was a dreadful moment to remember and also an indication of how much pressure I had been under, like everyone who worked there at the time.

Ahmed did not want to discuss that episode, and so the talk returned to everyday events and old anecdotes.

We drove past our old house and both felt very touched to see what was still stuck to the back door. There had been a break-in while we lived there and the thieves smashed the window in the kitchen door. I repaired it by nailing the lid of a wooden box sent from Sweden. Our family had packed it full of food from home. The address label on the lid read “To Doctor Hans Rosling, Nacala,” and the text was still visible thirty years later.

It was striking that those two years, which had meant so much to us, had mattered so little in Nacala. We left the town and were still shocked by the hopelessness of the apparently stagnant life in the most remote villages, where little or nothing had changed. At the same time, we had been encouraged by the inspiring young Mozambicans we had met.

On the last day of our return visit to Mozambique, we had been invited by a seventy-six-year-old lady to take afternoon tea. She had been born in the USA but had become a Mozambican citizen long ago. She shared with us her very realistic, factual take on her country’s development. Her views were based on a deep understanding of what building the nation of Mozambique had meant. Her name was Janet Mondlane.

Agneta and I had met Janet in Sweden in the autumn of 1968. She had been one of our very first guests for supper in our shared student apartment.

Janet was born in the 1930s in Illinois. At the age of seventeen, she attended a talk at the local church in Geneva, Wisconsin, given by Eduardo Mondlane, about the future of Africa. Eduardo had grown up in rural Mozambique and had just arrived to begin his university studies in the USA when he and Janet met. They married a couple of years later and had three children together before they moved to Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. Eduardo became the leader of FRELIMO, the Mozambican liberation movement, and organized its headquarters there in neighboring Tanzania. Unlike Europe’s other colonial powers, Portugal’s fascist regime had no intention of giving up its African colonies.

While in Tanzania, Janet Mondlane took on responsibility for running an education center to help Mozambicans in exile. She had come to Sweden to raise money for her project. I remember well how surprised Agneta and I had been by her conversation over dinner in 1968. She spoke like a true Mozambican, even though she had never set foot in the country. She impressed us, just as her husband had done when I met him a year or so earlier, with her ability to think ahead, beyond independence and far into the future. She was setting up courses for teachers who would one day educate the next generation of teachers in the independent Mozambique.

Eduardo was killed only a year later. After the 1975 day of independence, as the widow of the country’s first leader, Janet Mondlane moved to Maputo, its capital. We never met her while we were living there but now we were invited for tea. We had a friend in common, Julie Cliff, professor of epidemiology in Maputo. It was Julie who arranged for us to see Janet, forty-three years after we last met.

Her home was in a beautiful spot on the top of a hill in the center of the city. You could see the harbor entrance from her windows. Her first-floor flat was modest, though. We recognized her at once. Her smile was as charming as it had been so long ago.

“Welcome,” she said. “At last, I have a chance to return your invitation.”

After a quick tour of her home, when we were seated on her sofa, I simply had to ask her about the past: “Do you really remember having supper with us in 1968, in our tiny student apartment?”

She laughed happily and slapped her palms against her legs.

“I sure do! I don’t remember what we ate, but I remember you served the meal in the kitchen,” she said.

Agneta and I looked at each other, thinking the same thing: our guest had remembered the cultural oddity of serving dinner in the kitchen even though our sitting room had enough space for a formal dining table. Janet quickly read our thoughts and took our hands in hers.

“I also remember how young we all were, and how much at home I felt in your company. You were so interested in our struggle for independence,” she said. “But tell me: do you think Mozambique has changed since you were working here thirty years ago?”

She nodded agreement when I mentioned the greater number of doctors in Nacala, and she was even more pleased to hear Agneta speak about the new primary schools in most suburbs and villages, and how senior school classes had been added where there was only junior teaching before. We had both been delighted and impressed to see teenage boys and girls streaming into newly built school buildings painted in lovely colors.

Then we had to mention our despair at seeing the extreme poverty that still existed in the left-behind villages, and the tone became more subdued. We asked Janet about politics, governance and funding. Was aid money used in the best possible way to further economic growth? How corrupt were the community leaders really? And the question that Janet often had to deal with: if your husband were alive, would corruption be less extensive?

She was very composed and serious when she answered our questions, like a friend sharing something very important with us.

“Being head of state in one of Africa’s poorest countries is very difficult: possibly the toughest, most challenging job in the world. People are looking to you to meet many and varied needs—from those who live in extreme poverty to members of your own extended family. So many individuals depend on you. You have been helped by them through your life and now they expect you to reciprocate.

“Honestly, I can’t be sure how my husband would have turned out as president. Maybe neither better nor worse than the presidents that followed him. And I think our current one, Armando Guebuza, is doing well.”

Janet explained what she had observed as Mozambique was being built. The vision she and her husband had shared when they returned to Africa fifty years ago had now become reality. The former colony was now a relatively stable, independent country with elected presidents in lawful succession. The people were now much better educated. The university in the capital, named after Janet’s husband, not only trained teachers and other professionals but was developing its own areas of research specialization.

“It all takes time. Looking from outside, you tend to see our failures. There are still so many serious problems that obscure how far we have come,” she said. “What you say about Nacala fits with what I see—lots of progress but still so much more to do.”

Then she became very serious. She put down her cup of tea and cake to free her hands so that she could gesture to emphasize her message.

“Considering where Mozambique started, and how far we aim to go, thirty years is not a very long time.” Development must be allowed to take its time.

Some things, however, cannot wait. One case in point: a deadly virus able to cross oceans. My most terrifying and challenging job began in 2014, when ebola broke out in western Africa.