TRAINING

PREPARATION FOR KNIGHTHOOD

Training began when about ten years old, though in some cases it could be when as young as seven. As a page, the new recruit would be taught how to keep ladies company, how to sing and dance and recite poetry. He would start to handle practice weapons and learn about horses. When about 14 years old, the boy graduated to the role of squire, the word being derived from the French ecuyer, meaning a shield bearer. The youth now trained in earnest with weapons. He cut at the pell or wooden post, wrestled with and practised against other squires or knights. When pulled on a wooden horse by comrades, or mounted on a real horse, he tried to keep his seat when his lance rammed the quintain, a post on which was fixed a shield. Some had a pivoting arm, with a shield at one end and a weighted sack at the other; if a strike was made the rider had to pass swiftly by in order to avoid the swinging weight.

The youth came to know how to control the high-spirited stallions that knights rode. He learned to control the horse with his feet and knees when the reins were dropped so he could slip his arm through the enarmes of the shield for close combat. He became used to the weight of the mail coat and to the sensation of wearing a helm over mail and padding. He learned to swing up over the high-backed cantle of the saddle while wearing all his equipment. As well as acquiring these skills, he was now apprenticed to a knight, who might have several squires depending on his status. He had to look after the armour, cleaning mail by kicking it round in a barrel containing sand and vinegar, to scour between the links. Helmets needed polishing and oiling if they were in store. He helped look after the horses and ordered the knight’s baggage.

HORSES

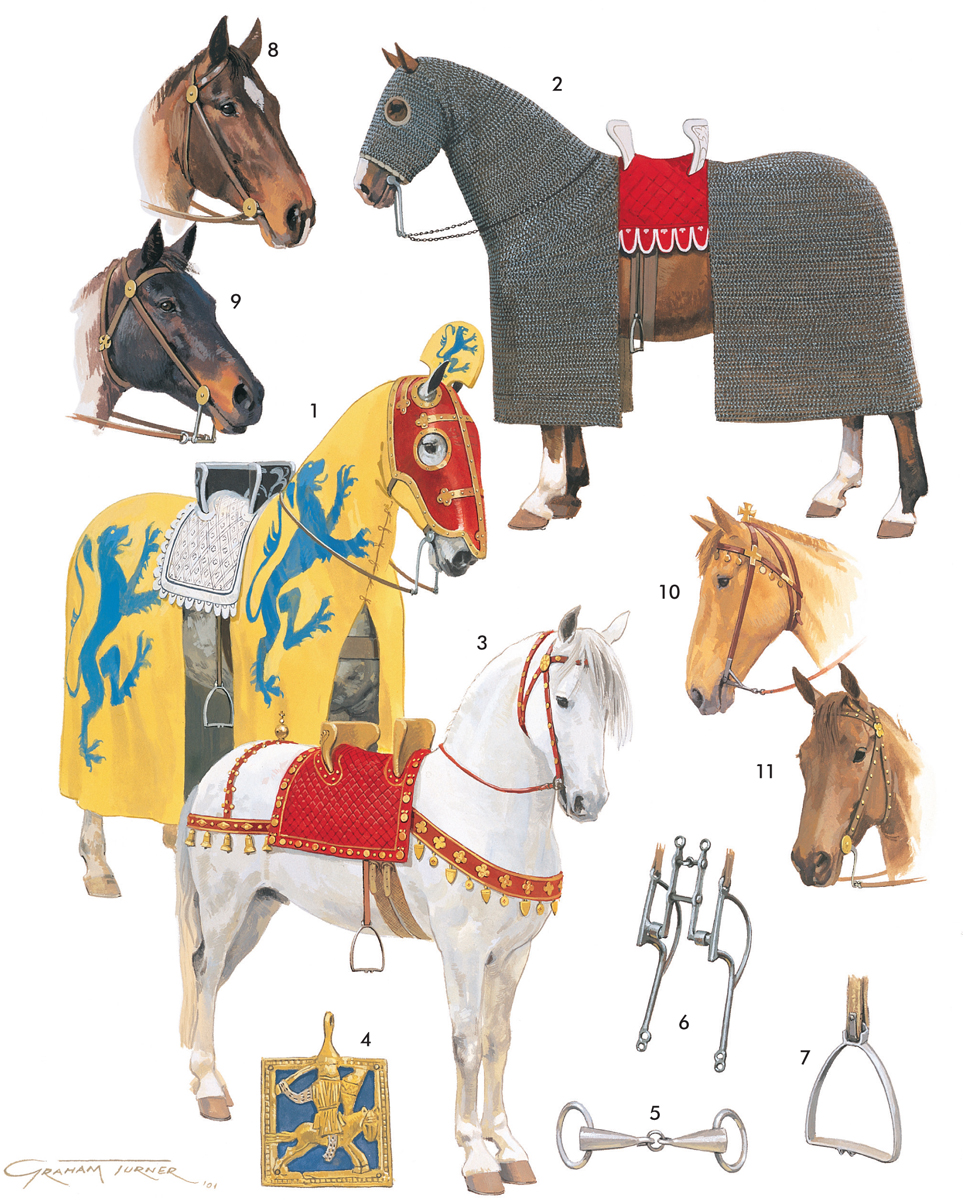

Horses were essential to a knight, and included a warhorse, the destrier or courser, a good riding horse, the palfrey, and rounceys for squires or servants. Sumpters for baggage, or wagon horses, were also needed. 1) The warhorse is shown in a full caparison (a cloth covering for protection or decoration, also called a trapper). 2) A mail trapper and chain reins to prevent cutting. 3) Palfrey with harness decorated with pendants and bells. 4) Harness pendant with backplate secured by a rivet at each corner. 5) Snaffle bit. 6) Curb bit, Museum of London. 7) Stirrup. 8) Bridle with snaffle. 9–11) Bridle styles with curb bits, c.1250.

As he grew older he also had to follow his lord into battle. In many cases this duty was probably carried out as described in the 13th-century Rule of the Templars, where each knight had two squires. On the march they went ahead of the knight, weighed down with equipment and with the led horses. As the knights drew up for battle, one squire stood in front of his master with his lance and shield, the other in the rear with the horses. When battle was imminent the first squire passed the lance and shield to his master. The second withdrew with the horses. When the knights charged, the squire riding the spare warhorse followed after his master, to remount him if the first horse was killed or blown. The squire’s job was also to extricate his master from the press if wounded.

THE HUNT: Deer were sometimes hunted from horseback: evidence suggests that a deer was picked out, then relays of hounds set along paths the quarry would likely take. When the beast was brought to bay, it was usual to wait for the lord to kill the animal by a sword-thrust through the shoulder into the heart.

Some squires were required to care for their lord as a manservant would. The squire learned how to bring in the more important dishes at dinner and to carve them in public. He was taught to hunt in the field, a good exercise, and the arts of falconry and venery, including how to ‘break’ a kill. To kill deer a squire or knight sometimes handled a bow or, less likely, a crossbow, though he would not use these on the battlefield. Some might be given lessons by a clerk or priest, though many were still illiterate.

KNIGHTHOOD

Somewhere between the ages of 18 and 21, the successful squire was initiated into the ranks of knighthood. Any knight could bestow this honour, but it usually fell to the lord of the squire’s household or even the king if the boy was at court. Sometimes knights were made on the battlefield before action, being expected to fight hard but also able to lead men. Simon de Montfort knighted the young Earl of Leicester and his companions before the battle of Lewes in 1264. Sometimes a squire might be knighted after a battle, a reward for valiant deeds. Usually, however, the process entailed a costly ceremony with all the trimmings, an increasingly onerous burden on many families, since a feast would be expected and perhaps a tournament as well. The church had by now become inextricably involved with the ideas of chivalry and knighthood, though it could never achieve such a hold over the creation of knights as it had with the crowning of kings, simply because too many knights were of only modest means and could not afford any great proceedings.

Sir John Dalyngrigge built Bodiam Castle in Sussex in 1385 against the threat of French attacks, which never materialized. It is of square plan, with domestic buildings along the inner walls. The lower parts of the walls are served by early gun loops. (jans canon/CC BY 2.0)

A full-blown ceremony would often include many or all of the following elements. The hair and beard (if worn) were trimmed. The day before the ceremony the candidate had a bath, from which he arose clean, a reflection on baptism. He might stand vigil in the chapel all night, his sword laid on the altar, so that he could spend the time in prayer and thoughtful meditation. The young man was then clothed, the meaning of the symbolic colours and accoutrements being explained in a French poem written between 1220 and 1225: a white tunic for purity; a scarlet cloak to represent the blood he is ready to spill in defence of the church; brown stockings, representing the earth that he will return to in time, an eventuality for which he must always be prepared; a white belt symbolizing purity; gilded spurs showing that he would be as swift as a spurred horse in obeying God’s commands; the two edges of his sword symbolizing justice and loyalty, and the obligation to defend the weak; the cross-guard echoing the cross of Christ. The candidate progressed to the assembled throng, for with no written certificate, even low-key ceremonies needed witnesses. His sword was belted on and spurs set on his feet.

The aspirant was then knighted by a tap on the shoulders with a sword, or perhaps still by the buffet often given previously, a symbolic blow that was the only one the new knight had to receive without retaliation. On the other hand, it may have symbolized the awakening from evil dreams and henceforth the necessity to keep the faith (as mentioned in a prayer book of 1295). Alternatively, it might have been to remember the knight who delivered it. It may even have derived from the habit of boxing the ears of young witnesses to charters to make sure they remembered the occasion, but it is not certain. Words of encouragement and wisdom were exchanged, along the lines of protecting the church, the poor, the weak and women, and refraining from treason. The new knight then displayed his prowess, sometimes in a tournament, and there was celebrating. A number of squires were sometimes knighted together.

Squires were sometimes knighted before a battle, producing new knights keen to fight bravely to uphold their honour, and as they might be needed to lead troops – something squires were not supposed to do. Edward III made new knights before a raid into Scotland in 1335. Knighting could also be performed after a battle, such as at Crécy in 1346, when Edward III declined to send help to his hard-pressed son, the Black Prince, telling the messenger to let the boy win his spurs, which he did.

By 1500, times had changed. Men of knightly rank did not always wish to fight, and not everyone had come from a background of mounted warriors. There were plenty of other activities, such as running estates, farming, mercantile interests in towns, local government and attending parliament as knights of the shire. Some were naturally attracted to the battlefield, however.