Function isinstance reports whether an object is an instance of a class—that is, whether an object has a particular type:

| | >>> isinstance('abc', str) |

| | True |

| | >>> isinstance(55.2, str) |

| | False |

’abc’ is an instance of str, but 55.2 is not.

Python has a class called object. Every other class is based on it:

| | >>> help(object) |

| | Help on class object in module builtins: |

| | |

| | class object |

| | | The most base type |

Function isinstance reports that both ’abc’ and 55.2 are instances of class object:

| | >>> isinstance(55.2, object) |

| | True |

| | >>> isinstance('abc', object) |

| | True |

Even classes and functions are instances of object:

| | >>> isinstance(str, object) |

| | True |

| | >>> isinstance(max, object) |

| | True |

What’s happening here is that every class in Python is derived from class object, and so every instance of every class is an object.

Using object-oriented lingo, we say that class object is the superclass of class str, and class str is a subclass of class object. The superclass information is available in the help documentation for a type:

| | >>> help(int) |

| | Help on class int in module builtins: |

| | |

| | class int(object) |

Here we see that class SyntaxError is a subclass of class Exception:

| | >>> help(SyntaxError) |

| | Help on class SyntaxError in module builtins: |

| | |

| | class SyntaxError(Exception) |

Class object has the following attributes (attributes are variables inside a class that refer to methods, functions, variables, or even other classes):

| | >>> dir(object) |

| | ['__class__', '__delattr__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', |

| | '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', |

| | '__init_subclass__', '__le__', '__lt__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', |

| | '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', |

| | '__subclasshook__'] |

Every class in Python, including ones that you define, automatically inherits these attributes from class object. More generally, every subclass inherits the features of its superclass. This is a powerful tool; it helps avoid a lot of duplicate code and makes interactions between related types consistent.

Let’s try this out. Here is the simplest class that we can write:

| | >>> class Book: |

| | ... """Information about a book.""" |

| | ... |

Just as keyword def tells Python that we’re defining a new function, keyword class signals that we’re defining a new type.

Much like str is a type, Book is a type:

| | >>> type(str) |

| | <class 'type'> |

| | >>> type(Book) |

| | <class 'type'> |

Our Book class isn’t empty, either, because it has inherited all the attributes of class object:

| | >>> dir(Book) |

| | ['__class__', '__delattr__', '__dict__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', |

| | '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', |

| | '__init_subclass__', '__le__', '__lt__', '__module__', '__ne__', '__new__', |

| | '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', |

| | '__str__', '__subclasshook__', '__weakref__'] |

If you look carefully, you’ll see that this list is nearly identical to the output for dir(object). There are three extra attributes in class Book; every subclass of class object automatically has these attributes in addition to the inherited ones:

| | >>> set(dir(Book)) - set(dir(object)) |

| | {'__module__', '__weakref__', '__dict__'} |

We’ll get to those attributes later on in this chapter in What Are Those Special Attributes?. First, let’s create a Book object and give that Book a title and a list of authors:

| | >>> ruby_book = Book() |

| | >>> ruby_book.title = 'Programming Ruby' |

| | >>> ruby_book.authors = ['Thomas', 'Fowler', 'Hunt'] |

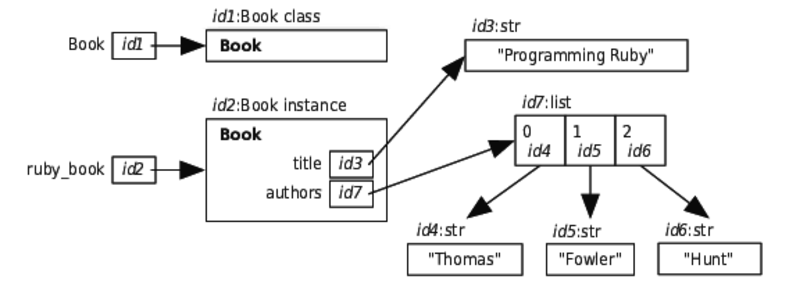

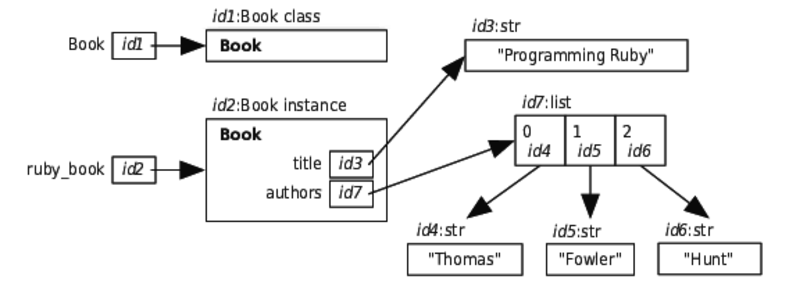

The first assignment statement creates a Book object and then assigns that object to variable ruby_book. The second assignment statement creates a title variable inside the Book object; that variable refers to the string ’Programming Ruby’. The third assignment statement creates variable authors, also inside the Book object, which refers to the list of strings [’Thomas’, ’Fowler’, ’Hunt’].

Variables title and authors are called instance variables because they are variables inside an instance of a class. We can access these instance variables through variable ruby_book:

| | >>> ruby_book.title |

| | 'Programming Ruby' |

| | >>> ruby_book.authors |

| | ['Thomas', 'Fowler', 'Hunt'] |

In the expression ruby_book.title, Python finds variable ruby_book, then sees the dot and goes to the memory location of the Book object, and then looks for variable title. Here is a model of computer memory for this situation:

We can even get help on our Book class:

| | >>> help(Book) |

| | Help on class Book in module __main__: |

| | |

| | class Book(builtins.object) |

| | | Information about a book. |

| | | |

| | | Data descriptors defined here: |

| | | |

| | | __dict__ |

| | | dictionary for instance variables (if defined) |

| | | |

| | | __weakref__ |

| | | list of weak references to the object (if defined) |

The first line tells us that we asked for help on class Book. After that is the header for class Book; the (builtins.object) part tells us that Book is a subclass of class object. The next line shows the Book docstring. Last is a section called “data descriptors,” which are special pieces of information that Python keeps with every user-defined class that it uses for its own purposes. Again, we’ll get to those in What Are Those Special Attributes?.