FOR THE NEXT DAY and a half the texts flew back and forth between the Kingdom Keepers. Finn used lunchtime to keep Amanda apprised of developments: no one had seen or heard from Wanda; Philby had buried himself in research, finding out everything he could about disappearing inks, and believing they should try to return to Wonders to try out his theories; Charlene was consumed with trying out for a dancing part in a school pageant.

“What about Maybeck?” Amanda asked Finn as they sat together in the lunchroom.

“He texted Philby to tell him to bring him the paper box this afternoon, after school. Said he figured something out.”

“That sounds promising,” Amanda said.

“What about Jess?” Finn asked.

“She’s fine,” Amanda answered dismissively, without a moment’s thought.

“I’m just asking,” he said.

“Who said you weren’t?”

“As in: has she had any more…uh-oh.”

Lousy Luowski was headed in their direction with a tray bearing only a dish of jiggling lime green Jell-O. Finn thought he had a pretty good idea what Luowski had in mind for the Jell-O.

“Hello, Greg,” Amanda said in a disarmingly warm voice.

Her tone stopped Luowski in his tracks. The dish of Jell-O bumped against the lip of his tray and stopped.

“We’ve got some unfinished business,” Luowski said. Mike Horton nodded at his side, like a translator.

“Greg,” Amanda said softly, drawing him in. “Have you heard about the wind here at school?”

“That’s a trick question,” Mike Horton whispered too loudly into Luowski’s ear. “Wind is invisible, in the first place.”

“That’s a trick question,” Luowski said.

“Think hard, Mike,” she said. “Science class about a month ago when Denny Fenner shoved Lois Long into the corner.”

“And all the beakers went flying off….” Horton stopped himself.

“And broke all over the floor,” Amanda said.

Horton nodded, his skin going pale.

“What’s going on?” Luowski asked, taking another determined step toward Finn.

“It wasn’t pretty,” Horton answered.

Luowski now had the dish of Jell-O in hand, but an arm’s length from the top of Finn’s head.

“What I’ve heard,” Amanda said, fixed on Luowski unflinchingly, “is that the wind is actually like some kind of ghost that inhabits the school and helps defend the innocent.”

At that moment, Luowski’s hair lifted off his oily face, blowing straight back. His shirtsleeves fluttered and rippled. Horton’s hair was caught by the wind as well, but not nearly in the same way. Luowski had to lean forward steeply just in order to remain standing.

“What…the…heck…is…happening?” The terror in his eyes conveyed Luowski’s predicament. If he stood up straight he was going to be blown over backward, but the gale-force wind seemed confined to him, with only a tiny fraction spilling past behind him.

The green Jell-O cubes were no longer square, but stretched into trapezoids. Several of them skidded across the dish. One escaped, splatting onto Luowski’s shirt.

“Stop it!” Luowski said to Finn, who just shrugged. “Stop it, you witch!” he said to Amanda.

“Me?” she gasped, backing her chair up as if afraid of it. “I don’t think ghosts hear so good, Greg. I’ve heard you have to scream to get their attention. You have to scream an apology.”

Whatever force held Luowski suddenly doubled. He was leaning impossibly far forward, like a ski jumper, the soles of his running shoes fixed to the cafeteria’s tile floor.

Some of the other students turned. Only a few seconds had passed since the wind had begun to blow.

Amanda had never stopped staring at Luowski, whose red face was now gripped in such terror that he looked like a big baby.

“I don’t think they can hear you,” Amanda said.

“I’m sorry! I’m so-o-o-o-o sorry!” Luowski crowed.

At that instant, the Jell-O flew off the dish and into Luowski’s face and for a moment he wore a slimy green mask with only his eyelids popping through. Then the wind stopped all at once, as if a door had been shut, and the forward-leaning Luowski fell flat on his face, to the delight of most of the cafeteria.

There were cheers and applause.

Finn looked across the table to see Amanda’s face filled with the light of mirth, her eyes sparkling, her smile a mile wide. She chortled and covered her laughing mouth with her hand, and for the first time looked away from Luowski and over at Finn, whose startled expression clearly caught her attention. He shook his head faintly side to side. She wiped the smile off her face, suddenly self-conscious.

“I think the school ghost has your number, Greg,” she said, as she grabbed her tray and stood up. “I’d be careful of making threats if I were you.”

The green-faced Luowski rolled over and looked up at Finn, about to say something when he thought better of it. Instead he turned his growl onto Horton, who had laughed himself to tears.

“Where are we meeting after school?” Amanda asked Finn calmly as they were returning the silverware and dishes off their trays.

“That was you,” Finn mumbled. “You can direct it like that?” He’d seen Amanda use her power once before. There was no denying she was different.

“There are all sorts of things I can do that you don’t know about, Finn.”

“You can’t just…do that in school.”

“Of course I can,” she said. “Who’s going to believe anyone can do something like that? There will be a dozen explanations for what happened to Greg. None will involve me. Just wait and see.”

They left the cafeteria, on their way back to their lockers.

“Do other Fairlies act so—”

“Bravely?” she said, interrupting.

“I was thinking more like…stupidly,” he said.

“Ha, ha!”

“I’m serious. That was stupid.”

“Greg Luowski was going to smear green Jell-O into your hair. The least you could do is thank me.”

“You’re right: thank you. But you should follow the same rules as the rest of us. You’re a DHI now. You can’t draw suspicion.”

“I’m a DHI who’s about to be sent back to Maryland to a halfway house full of Fairlies. I’m desperate, Finn.”

“And how is misbehaving going to help your situation?”

“How’s it going to hurt it?” she asked. “If I can do a little good before I leave, isn’t that better than doing nothing at all?”

He knew he should have an answer for that. Even something trite would have been welcome. But a part of him understood that she was right: when it came to doing good, it was better to do something risky rather than nothing at all. He felt the same way about attempting to find Wayne.

“Where and when?” she asked, just before they split up off the stairs.

“Jelly’s place right after school.”

“Gotcha,” she said, ascending the stairs effortlessly, as if a stiff wind blew at her back.

* * *

Maybeck lived above Crazy Glaze, his aunt Jelly’s pottery shop. The shop’s front room was crowded with shelves of pale, unfired clay vessels that customers painted and adorned with glazes and other treatments, while its back room contained more raw stock, a desk in the corner, and a small kiln. The two big kilns were out back, as were three motorized pottery wheels, and two manual ones; the whole back area was covered in a gray wash that spoke of years of use. Adjacent to the desk in the back room was a drafting table, and next to it a sewing machine and a light table, each pertaining to a particular hobby of Maybeck’s multitalented guardian.

The heavyset woman, whose real name was Bess, had not been given her nickname as a result of her girth—substantial though it was—but on account of her own mispronunciation of the name Shelly as a child. Jelly had a choir girl’s smile, kind eyes, and four chins. Her voice was low and husky, and when she looked at you it felt as if she could see things others could not—like a fortune-teller or priest.

With all the Kingdom Keepers assembled in the tight space, Jelly opened the kiln and carefully extricated a baking sheet containing a dozen chocolate chip cookies, which explained the incredible smell of the place. She moved some bricks and pulled out a second sheet of the oatmeal variety. Maybeck headed upstairs and returned with a box of cold milk and the after-school ceremony began. Once lips were properly licked free of remaining crumbs and the last drops of milk had slid down sugary throats, Jelly left them, shutting the door to the outer room to deal with her customers.

“So,” Maybeck said, “I was doing an art project for school, this thing of layering colors, when something occurred to me, so I texted Philby. I suppose you know that or you wouldn’t be here. The point being, I could be way wrong about all this, and I didn’t mean to call a massive meeting or anything.”

“No one forced us to be here,” Willa said. “We wouldn’t have come if we hadn’t wanted to.”

“Yeah, right. The thing is,” Maybeck continued, “we all know how tricky our friend is. He’s always doing stuff that has multiple meanings, multiple layers. That’s what got me, I think: layers. Working with the colors. ’Cause the thing is, you layer yellow over red and you get orange, orange over yellow and you get yellow-orange. It’s all about what’s in front and what’s behind.”

“You kinda lost me there,” Charlene said.

“It’s the shapes on the box. They’re like symbols or something. Curves. Lines.”

“Code?” Philby said.

“Yeah, I think. In a way at least.” Maybeck extended his open palm and Philby produced the small paper box and handed it to him. Maybeck switched on the light box, which consisted of a sheet of white glass in front of a powerful, uniform white light, like the devices radiologists use to view X-rays.

“My theory,” he said, continuing, “is that Wayne expected us to figure out what others would not: that what alone looked like symbols combined to something more.”

“You mean, kind of like us?” Charlene said. “We make more sense as a group.”

“We’re capable of more,” Philby added.

“Exponential,” Jess added.

Finn realized this was something new—the DHIs talking about themselves as a group. It had always been there, lingering just below the surface—the idea that Wayne had intended them to act as a group, not as individuals, but this was the first he could remember anyone actually acknowledging it.

“The whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” Finn said.

“Yeah, like that, I suppose,” Maybeck said, “but all I’m interested in is layers.” He held up the box. “See, on this side is a parentheses—the left side. Turn the box around, and there’s another parentheses, also the left, like a stretched C.”

“Matching,” said Willa.

“You think they’re both meant to be capital Cs?” Philby asked Maybeck.

Maybeck didn’t answer. He spun the paper cube to show a different face. “And this weird shape.” He turned the box to show the opposite side. “And this one.”

“I’ve looked through a dozen languages and a few hundred fonts: Cyrillic, Greek, Roman, of course,” said Philby. “Those symbols aren’t part of any modern alphabet. A few of those marks are pretty close to some accents used in modern languages, but I don’t see where that gets us.”

“Because it’s Wayne,” Maybeck said. “If I’m right, it’s not about the individual symbols, but the way they combine.”

He moved the paper box closer to the light table, the left parentheses facing the kids. For a moment the box caught the light and glowed like a lightbulb; it appeared to grow between Maybeck’s fingers. Then, as he delivered it atop the light box’s glass plate, the mark on the opposing face came into crisp focus. The kids pressed together in a tight huddle.

Charlene gasped.

“OMG!” said Willa.

“I thought so,” said the ever modest Maybeck. “The left parentheses joins the right parentheses and together—”

“They form an O!” said Philby. “Our alphabet after all!”

Maybeck picked up the box, turned it, and replaced it. The letter was a backward N, but reversing the box formed the letter correctly. There was another, fainter, V, but it looked like something drawn and then erased. He rotated the box a third time. Each pair of images on the opposing sides of the cube’s six faces combined to form a letter.

“Turn it around!” Willa said. “It’s either a lowercase b, or a lower-, or uppercase, P.”

“Then it’s a P,” Maybeck said, “because the O and N are both uppercase.”

“Agreed,” Philby said, already grabbing a shaping tool and drawing the letters into some soft clay on the table beside him: P N O.

“Initals?” said Amanda. “A what-do-you-call-it?”

“Abbreviation?” said Jess.

“No,” said Amanda. “A…”

“Piano?” asked Charlene.

“Try again,” said Maybeck. “A different order.”

Philby wrote: N P O, then N O P.

Each of the kids was throwing out an idea of what the various letters stood for.

Philby moved the tool through the wet clay…O…

Before he’d reached the second letter Jess said quietly, “Open.”

The shouting stopped. The kiln hummed, or maybe it was the light box or the overhead lights.

“Open,” she said again. “O P N.”

“Open,” Maybeck repeated. “Of course.”

“That is so Wayne,” Willa said.

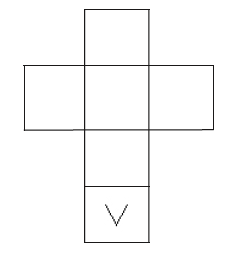

Maybeck carefully found the edge, sealed with a thin strip of tape. It took him a minute to locate a razor blade, but no one was going to suggest they hurry into this and tear the box in the process. At last, he ran the blade through the tape and the flap was loose. Two more incisions through the gaps, and all sides were free. Maybeck carefully unfolded the box.

“I’ve done this in math a hundred times,” said Philby. “It forms a—”

“It’s a cross,” said Amanda. Maybeck turned the box around in his palm to make it a proper cross. The V now pointed down, toward his wrist.

“That’s not a V,” said Finn. “It’s a point.”

Philby said, “It’s a tip of a—”

“Sword,” said Maybeck.

“Only boys would see that as a sword,” said Charlene cynically. “It is so obviously a cross.”

“It’s a sword,” Philby said, agreeing with Maybeck. “This is Wayne, don’t forget.”

“It’s a cross. And in Epcot, that means France.”

“And it was outside of France,” Amanda said to Jess, “that you felt…you know…felt something the first time you crossed over.”

Jess nodded timidly.

Willa said, “And France also means Notre Dame. The Hunchback—that’s Disney.”

“It’s a sword,” Maybeck repeated.

“And in Epcot,” Philby said, mimicking her, “that’s…” He squinted his eyes. “Norway. The Maelstrom ride—”

“I love that ride!” said Finn, immediately wishing he hadn’t.

“—has a sword in it,” Philby said, finishing his thought.

“Impressions de France,” Willa said, “is a film in Epcot’s France. It shows the cathedral, as does an exhibit while you’re waiting to get into the film. He’s left us another clue or the answer there. Maybe he’s being held in France.”

“Maybe he’s being held in Norway,” Philby fired back.

“Maybe we split up and figure this out,” said Finn.

“Divide and conquer,” said Amanda. “Girls to France, boys to Norway.”

“Tonight,” said Maybeck.

“Nine o’clock,” said Philby. “I can cross over and program the projectors.…I have to cross over to program them; there’s no way past the firewalls from out here. I can’t promise the system won’t go down at midnight. I tried to reprogram that, but things got weird, and I’m not sure I did any good.”

“That will give us about three hours,” said Charlene. “Isn’t that enough?”

Philby answered for the boys. “It depends on what we find.”