Chapter 2

The Appeal of Engines

In Detroit, Henry found a job at a company that made fire hydrants, pipes, and other items out of brass and iron. Henry learned how to run machines that made small metal parts. Needing money and full of youthful energy, he also took a second job at night repairing watches.

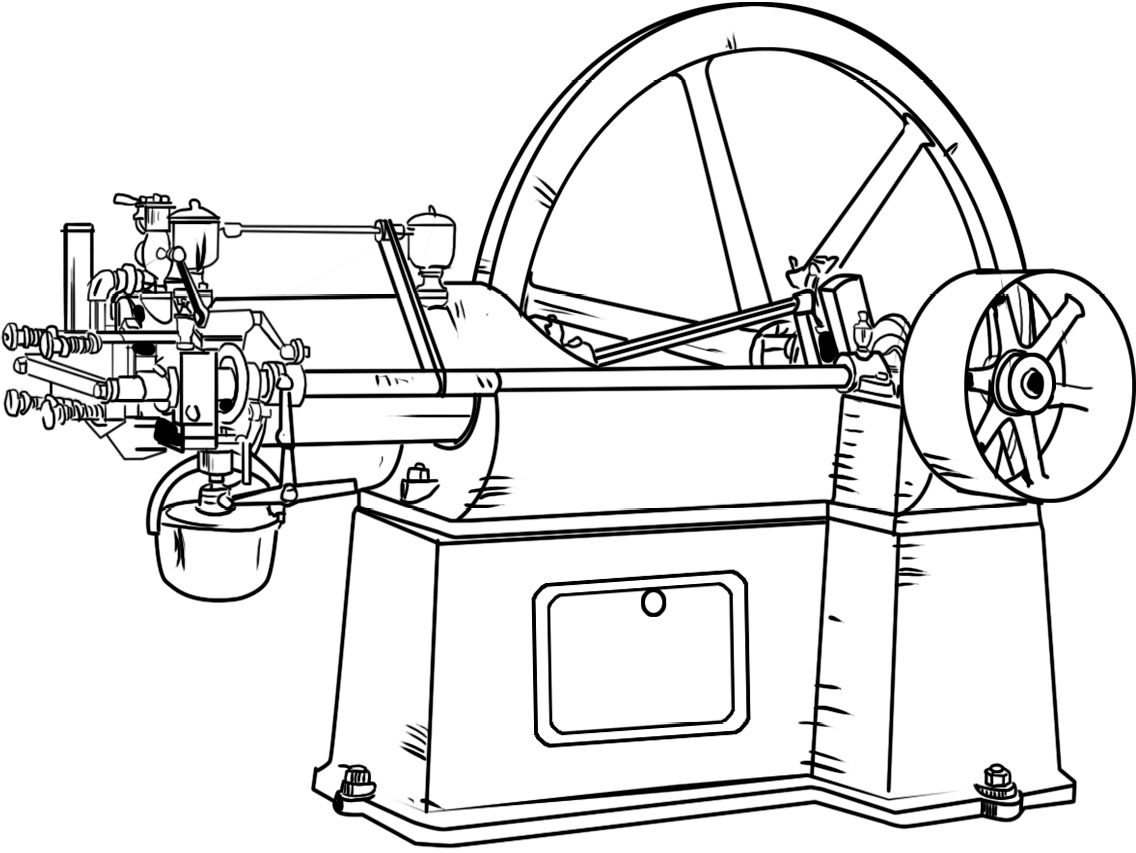

In his work, Henry met a number of skilled machinists and engineers. From them, he learned even more about steam engines. He also learned about a newer engine that ran on gas instead of steam, known today as the internal combustion engine. The gas was mixed with air and then lit to combust, or explode, inside a cylinder. This “explosion” moved a small metal piece called a piston, which could power a machine. Henry saw that a small engine like this could be used to move a vehicle forward.

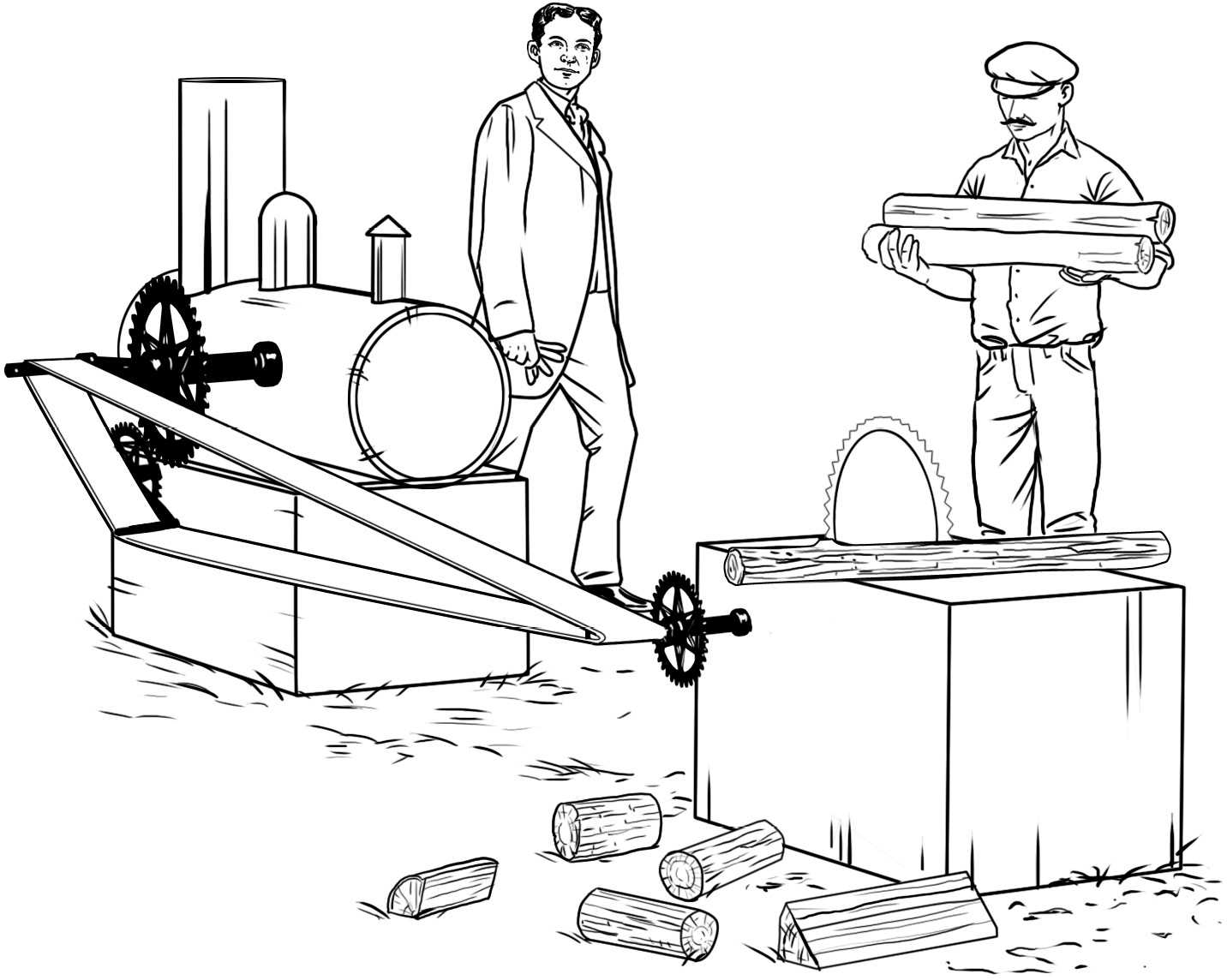

Henry soon found a new job that actually brought him back to steam engines—and back to Dearborn. In 1882, a farmer named John Gleason hired him to visit local farms and charge people to use Gleason’s steam engine to power wood choppers and farm equipment. Henry found great pleasure in keeping the engine running smoothly and driving the little vehicle across the countryside.

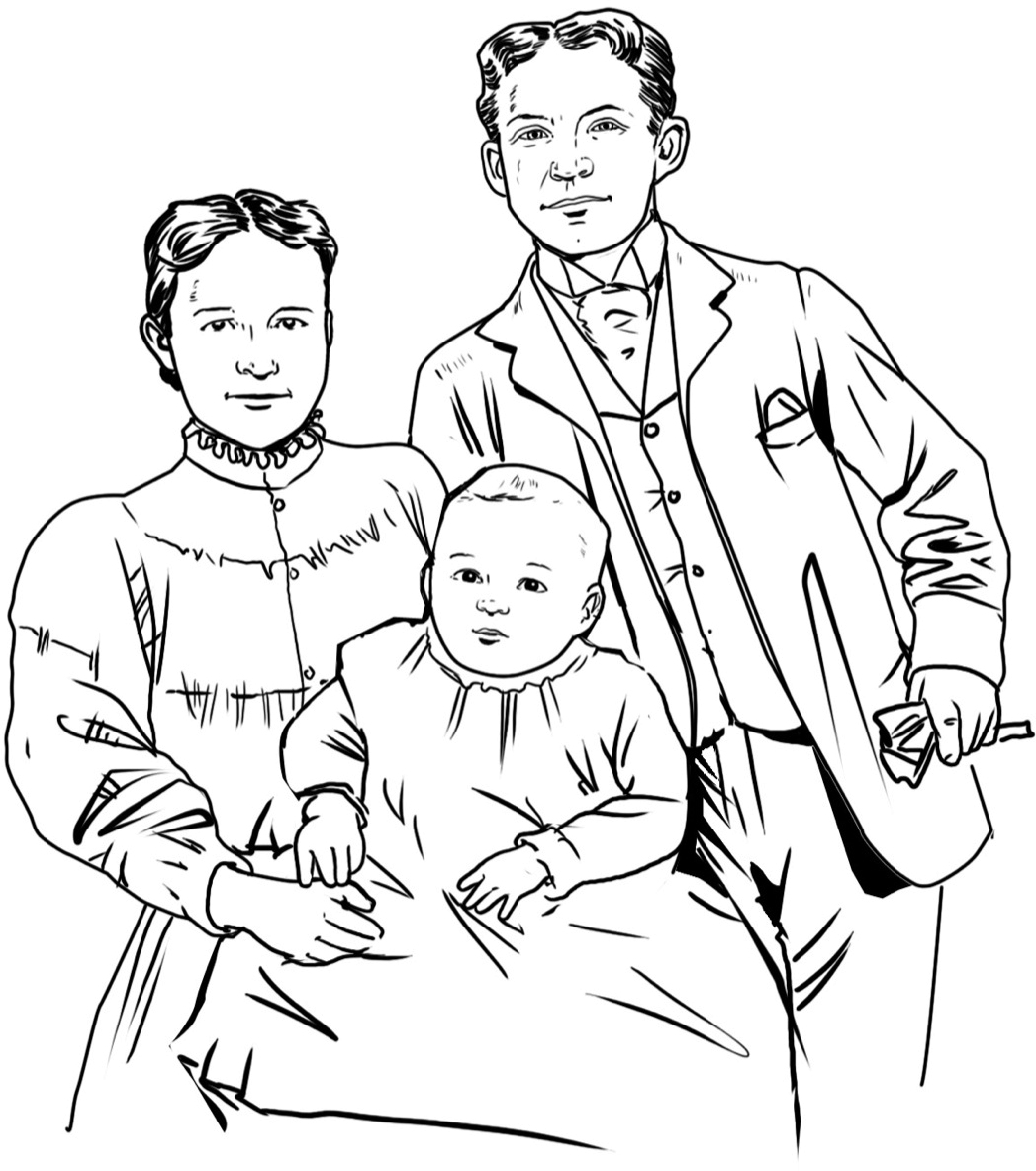

At the beginning of 1885, while attending a dance, Henry met Clara Bryant. He liked her immediately, and they began dating. Henry impressed Clara with a watch that he had made. She liked that he was a serious person and willing to work hard. They were engaged in 1886 and married two years later. Henry built them a house on land his father owned.

In 1889, Henry went to Detroit to fix a gas engine. He returned home with a new idea: he wanted to build a gas-powered car. The first car with a gas engine had already been built in Germany in 1885 by Karl Benz. But Henry thought he could improve on the design. Hearing his idea, Clara was convinced Henry could do it. Ford nicknamed his wife “the Believer,” because she never doubted his skills as an inventor. He wrote, “It was a very great thing to have my wife even more confident than I was.”

In 1891, he and Clara moved to Detroit. There, he hoped to learn everything he could about electricity. Electricity, he believed, was the key for creating the explosion to power a gas engine. Henry got a job at the Edison Illuminating Company. At the time, Thomas Edison owned several companies that provided electricity to cities in the United States. Henry’s main job was to fix the huge steam engines that generated electricity, and he did his job well.

In 1893, Henry and Clara’s only child was born—a boy they named Edsel, after one of Henry’s old friends. Edsel was only a few weeks old when Henry carried out one of his great early experiments.

Henry had a workshop behind his house where he worked on building a gas engine in his spare time. On Christmas Eve, he brought the engine into the family kitchen to test it. It took two people to run and required electricity, which Ford did not have in his simple workshop. Clara willingly helped. She poured in the gas as Ford turned a metal wheel that got the piston moving. Then, with a spark from the house’s electricity, air and fuel combusted, and the small engine began to run! Henry was happy, but not satisfied. “I didn’t stop to play with it,” he wrote. He wanted to build a bigger engine—one that could power a car.