Chapter 7

New Growth, New Challenges

It didn’t take long for the Ford Motor Company to expand far beyond Michigan. As early as 1904, Ford made cars in Canada, and he began building Model Ts in England in 1911. Dealers sold Ford cars from Russia to Brazil and many points in between. People around the world recognized the Ford name.

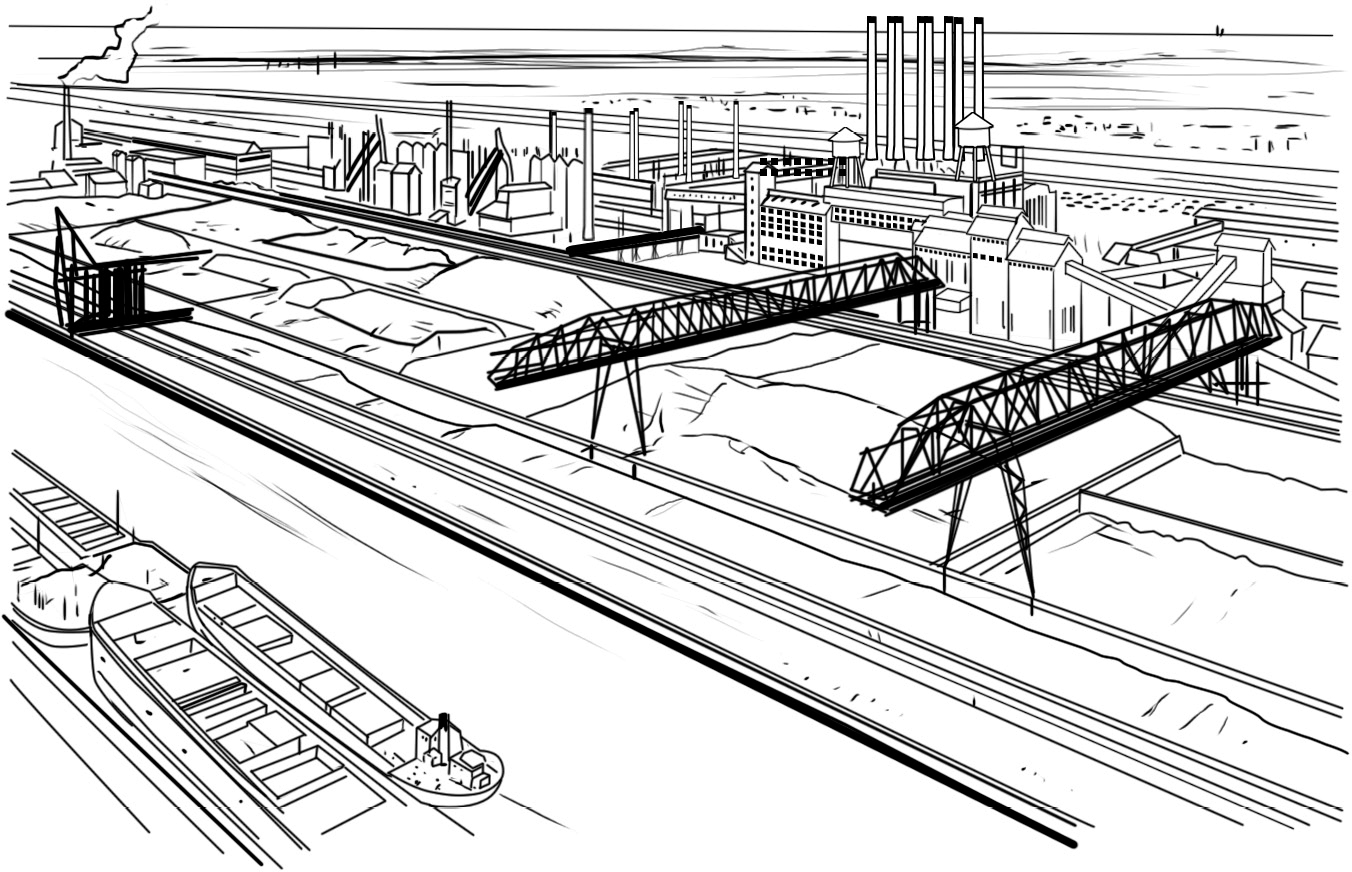

During World War I, Ford began building a new plant outside Dearborn. It was named River Rouge, after a nearby river. But Henry wasn’t interested in just another factory. At River Rouge he built a mini industrial city. Boats brought iron ore and coal to the site so the company could make its own steel. Other materials came by train to a railway station built right into the plant. Lumber was cut at a River Rouge sawmill. The lumber, coal, and iron ore all came from land that Henry owned. By controlling all parts of production, including raw materials, and making cars in huge numbers, Henry could continue to lower the cost of the Model T.

With his huge fortune, Henry also bought a radio station and a newspaper, which he used to promote and sell his cars. He also wanted to share his own personal and practical ideas for making the country better, just as he had made the car better.

Henry called the paper the Dearborn Independent. Each issue had one article that expressed his personal opinions. Henry often spoke out against bankers and investors; he believed they unfairly made money off of other peoples’ hard work, not by manufacturing or selling anything themselves. And some of his harshest words were directed at Jewish Americans. Articles in the Dearborn Independent said that Jewish people controlled many banks and other industries and that they were weakening the United States. Henry did not write the articles himself, but he did approve them to run in his paper.

These hateful articles angered Jews and non-Jews alike. Former presidents Woodrow Wilson and William Howard Taft were among the people who spoke out against anti-Semitism—the hatred of Jews that Ford was showing. To some people, Henry’s anti-Semitism reflected his lack of education. He had never trusted well-educated people—he preferred the simple farmers and mechanics he had grown up with. And Ford never claimed to be a genius. He was an inventor who knew how to make and sell cars. In 1927, when Henry finally realized he had upset Jewish Americans with the articles in the Independent, he made a public apology.

By that time, the man who had helped invent the modern age of mass production was thinking more about the past. Henry longed for the simpler times of his childhood. He restored the house he had grown up in and several other older buildings. He began building a huge antique collection that included furniture, clothing, and household items from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In 1928, Henry began building the Henry Ford Museum a few miles from his Dearborn home to display his collections.

But Henry didn’t just collect antiques. He found historic buildings and parts of buildings and moved them moved to Dearborn. One was the actual courthouse where Abraham Lincoln argued several legal cases when he was a young lawyer. Another was the workshop where Thomas Edison had created some of his greatest inventions. Although most of the building was not the original Menlo Park lab, Henry had every detail re-created at Greenfield Village, where he placed the buildings he found. The village, next to his museum, grew to contain more than eighty historic American buildings.

While Henry focused more and more on the past, his son Edsel was trying to think ahead to the future. The Ford Motor Company had been selling only the Model T for more than ten years. Edsel’s plan was to build a new car.

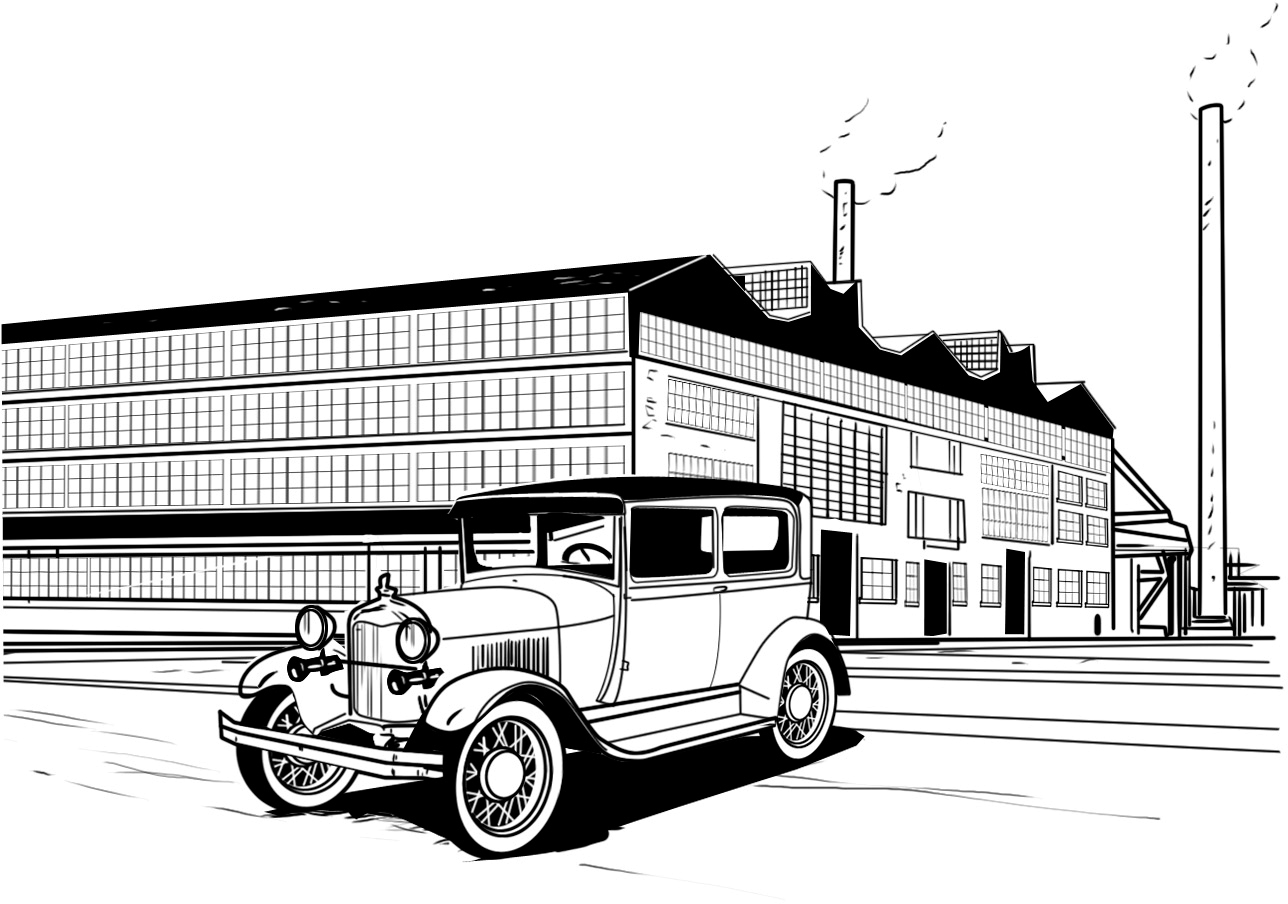

But Henry wasn’t easily convinced. It took five long years before he finally agreed to build the new model. He played an active role in designing it, just as he had with his first cars. In May 1927, just as the 15 millionth Model T was rolling out the door at the old Highland Park factory, the Ford Motor Company announced its new car, which had the very same name as its original car: the Model A!

The new Model A had windshield wipers, an automatic starter, and other modern features. It was also more powerful than the Model T. The Model A was an instant hit with American drivers. The car was barely more expensive than the Model T, and was a much better car. In 1929, production of the Model A peaked at more than 1.5 million cars. But then the Ford Motor Company, and the rest of the United States, hit a huge bump in the road—the Great Depression.

After World War I, farmers and many industries were producing more goods than people could buy. They were still growing and manufacturing at the same pace they had during the war. As a consequence, during the 1920s, companies began to fire and lay off workers in large numbers. Everyone who had lost their jobs could not continue to buy new things and pay their bills, so stores and banks went out of business. Henry Ford had to lay off workers, too, and he cut the salaries of others. By 1932, about 13 million Americans were out of work. The Great Depression sparked new interest in labor unions that would help workers keep their jobs.

Labor unions were group of employees who sought to improve wages and working conditions. If factory owners refused their demands, the workers could threaten to strike—refuse to work. The owners disliked strikes; they would be forced to stop production, which meant they would have no products to sell. They also didn’t want workers trying to tell them how to run their businesses. Unions fought for laws that helped all workers, such as shortening the workday to eight hours.

By the 1930s, workers in the auto industry wanted their own union, too. New laws, passed after the election of President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932, made it easier for workers to form unions. In 1935, the United Automobile Workers union (UAW) was formed.

Henry disliked labor unions and fought having them at his factories. He didn’t want anyone—investors or workers—telling him how to run his business. By 1937, Henry had hired security men to guard the Ford plant. That May, Henry’s guards fought with men who tried to organize for the UAW there. Other workers acted as spies for Ford, reporting anyone who supported the unions. Ford angered many Americans with his harsh treatment of his employees during the Great Depression. His support for workers by starting the $5 workday seemed long in the past. By 1941, other major automakers had allowed unions in their plants. Finally, Henry did, too. Although he loved the simple ways of the past, he realized that at times he could not always fight change.