Behavioral Science

Chapter Outline

Scientific Approaches to Knowledge

Criteria for Evaluating Theories

Theory, Research, and Application

The Interdependence of Theory, Research, and Application

The Uses of Behavioral Science and Theory

Suggestions for Further Reading

Questions for Review and Discussion

Why do people do what they do? How do biology, personality, personal history, growth and development, other people, and the environment affect the ways people think, feel, and behave? As you have learned from your other behavioral science courses, there are many ways to go about answering questions such as these, ranging from the casual observation of daily life that leads to the development of personal theories of behavior (for example, Wegner & Vallacher, 1977) to systematic empirical observation leading to the development of formal theories of behavior. As you have also learned, the casual observation approach, also sometimes called “ordinary knowing” (Hoyle, Harris, & Judd, 2002), is prone to errors that stem from basic cognitive processes (for example, Gilovich, 1991). Therefore, behavioral science takes the more systematic, scientific approach to knowing, which is designed to minimize the effects of those biases.

Behavioral science is composed of three interrelated aspects: research that generates knowledge, theory that organizes knowledge, and application that puts knowledge to use. Most scientists have a greater interest in one of these aspects than in the others (Mitroff & Kilmann, 1978). Nonetheless, complete development as a scientist requires an understanding of all three aspects (Belar & Perry, 1992). As the title of this book indicates, we will explore the research aspect of behavioral science in detail. But before doing so, we will put research into context by reviewing the nature of science and theory and by examining the interrelationships of research, theory, and application.

Science is a systematic process for generating knowledge about the world. There are three important aspects of science: the goals of science, the key values of science, and perspectives on the best way in which science can go about generating knowledge. We begin by reviewing each of these aspects.

The behavioral sciences have four goals: the description, understanding, prediction, and control of behavior.

Description. As a goal of science, description has four aspects. First, it seeks to define the phenomena to be studied and to differentiate among phenomena. If you were interested in studying memory, for example, you would need to start by defining memory, by describing what you mean by that term. Do you mean the ability to pick out from a list something previously learned, as in a multiple-choice test, or the ability to recall something with minimal prompting, as in a short-answer test? Description is also used to differentiate among closely related phenomena, to be certain we are studying exactly what we want to study. Environmental psychologists, for example, distinguish between (a) population density, the number of people per square meter of space, and (b) crowding, an unpleasant psychological state that can result from high population density (Stokols, 1972). High population density does not always lead to feelings of crowding. People who are feeling positive emotions rarely feel crowded in even very densely populated situations—think about the last time you were enjoying a large party in a small house. We return to this definitional aspect of the descriptive goal of science later, when we discuss the components of theories.

The third aspect of the descriptive goal of science is the recording of events that might be useful or interesting to study. Let’s assume, for example, your friend has been in an automobile accident, there is a trial to determine liability, and you attend the trial to support your friend. As the trial progresses, something strikes you as interesting: Although four witnesses to the accident had equally good opportunities to see what happened, their memories of the event differ significantly. Two witnesses estimate the car was moving at 30 miles per hour (mph), whereas two others say one car was going about 40 mph when it hit the other car. This inconsistency piques your curiosity, so you attend other trials to see if such inconsistencies are common, and you find they are. You have now described a phenomenon: Eyewitnesses can produce very inconsistent descriptions of an event.

Finally, science works to describe the relationships among phenomena. Perhaps in your courtroom observations you noticed that some kinds of questions led to higher speed estimates than did other kinds of questions. This discovery of relationships among phenomena can help you understand why certain phenomena occur—the second goal of science.

Understanding. As a goal of science, understanding attempts to determine why a phenomenon occurs. For example, once you determine eyewitnesses can be inconsistent, you might want to know why the inconsistencies exist, what causes them. To start answering these questions, you might propose a set of hypotheses, or statements about possible causes for the inconsistencies, that you could then test to see which (if any) were correct. For example, given courtroom observations, you might hypothesize that the manner in which a lawyer phrases a question might affect a witness’s answer so that different ways of phrasing a question cause different, and therefore inconsistent, responses.

But how can you be sure a particular cause, such as question phrasing, has a particular effect, such as inconsistent answers? To deal with this question, the 19th-century philosopher John Stuart Mill developed three rules of, or conditions for, causality; the more closely a test of a hypothesis meets these conditions, the more confident you can be that the hypothesized cause had the observed effect. The first rule is covariation: The hypothesized cause must be consistently related to, or correlated with, the effect. In our example, we would want differences in question wording to be consistently related to differences in response. The second rule is time precedence of the cause: During the test of the hypothesis, the hypothesized cause must come before the effect. Although this principle seems obvious, you will see in the next chapter that when some research methods are used, we cannot establish with certainty that a hypothesized cause did, in fact, come before the effect. The third rule is that there must be no plausible alternative explanation for the effect: The hypothesized cause must be the only possible cause present during the test of the hypothesis. For example, if you test your question-phrasing hypothesis by having one person phrase a question one way and another person phrase it another way, you have a problem. You have no way of knowing whether any response differences that you observe are caused by the different phrasings (your hypothesis) or by some difference between the people asking the question. For example, perhaps a friendly questioner elicits one kind of response, and an unfriendly questioner another. In contrast, if the same person asks the question both ways, differences in personality cannot affect the answer given. We address this problem of alternative explanations in more detail in Chapter 7.

Bear these rules of causality closely in mind; they will play an important role in the discussions of research strategies in the next chapter and throughout this book. By the way, if you tested the question-phrasing hypothesis according to these rules, as did Loftus and Palmer (1974), you would find that question phrasing does affect responses. Loftus and Palmer had people watch a film of a moving car running into a parked car. Some of the people estimated how fast they thought the moving car was going when it “smashed” into the other car; other people estimated how fast it was going when it “contacted” the other car. The average speed estimate in response to the “smashed” question was 40.8 mph, whereas the average estimate in response to the “contacted” question was 31.8 mph.

The scientific goal of understanding also looks for relationships among the answers to “why” questions. For example, you might want to know how well your question-phrasing hypothesis fits more general principles of memory (Penrod, Loftus, & Winkler, 1982). An important aspect of scientific understanding is the derivation of general principles from specific observations. Thus, if a thirsty rat is given water after pressing a bar, it will press the bar again; if a hungry pigeon is given a food pellet after pecking a button, it will peck the button again; if a child is praised after putting dirty clothes in a laundry hamper, he or she will do so again. These diverse observations can be summarized with one general principle: Behavior that is rewarded will be repeated. Systems of such general principles are called theories, which are discussed later in this chapter. Once general principles are organized into theories, they can be applied to new situations.

Prediction. As a goal of science, prediction seeks to use our understanding of the causes of phenomena and the relationships among them to predict events. Scientific prediction takes two forms. One form is the forecasting of events. For example, the observed relationship between Graduate Record Examination (GRE) scores and academic performance during the first year of graduate school lets you predict, within a certain margin of error, students’ first-year grades from their GRE scores (Educational Testing Service, 2009). When other variables known to be related to graduate school performance, such as undergraduate grade point average (GPA), are also considered, the margin of error is reduced (Kuncel, Hezlett, & Ones, 2001). Notice that such predictions are made “within a certain margin of error.” As you know from your own experience or that of friends, GRE scores and GPA are not perfect predictors of graduate school performance. Prediction in behavioral science deals best with the average outcome of a large number of people: “On the average,” the better people do on the GRE, the better they do in graduate school. Prediction becomes much less precise when dealing with individual cases. However, despite their lack of perfection, the GRE (and other standardized tests) and GPA predict graduate school performance better than the alternatives that have been tried (Swets & Bjork, 1990).

The second form taken by scientific prediction is the derivation of research hypotheses from theories. For example, one theory holds that people use information they already have stored in memory to understand, organize, and remember new information (Bransford, 1979). One hypothesis that can be derived from this theory is that people better remember information if they are first given a context that helps them understand it. As an example, consider this sentence: “The haystack was important because the cloth ripped.” How meaningful and understandable is that sentence as it stands alone? Now put it in this context: The cloth was the canopy of a parachute. Bransford (1979) and his colleagues predicted, on the basis of this theory, that people would be better able to understand and remember new oral, pictorial, and written information, especially ambiguous information, when they were first given a context for it. The experiments they conducted confirmed their hypothesis and thus supported the theory.

This process of hypothesis derivation and testing is important because it checks the validity of the theory on which the hypothesis is based. Ensuring the validity of theories is important because theories are frequently applied in order to influence behavior. If the theory is not valid, the influence attempt will not have the intended effect and could even be harmful.

Control. As a goal of science, control seeks to use knowledge to influence phenomena. Thus, practitioners in a number of fields use the principles of behavioral science to influence human behavior. The capability to use behavioral science knowledge to control behavior raises the question of whether we should try to control it and, if so, what means we should use. Behavioral scientists have discussed these questions continually since Carl Rogers and B. F. Skinner (1956) first debated them. It is because these questions have no simple answers that all fields of applied behavioral science require students to take professional ethics courses. However, as Beins (2009) notes, even if psychologists agree that control of behavior is appropriate, their ability to do so is limited. There is no single theory that can explain human behavior, and researchers with different theoretical orientations offer different predictions about how to change any one behavior. Hence, practitioners who take the perspective that alcoholism has a strong genetic basis would propose different treatment options than would practitioners who believe that alcoholism stems from the interaction between genetic and environmental factors (Enoch, 2006). Furthermore, as noted earlier, scientists’ ability to accurately predict any one individual’s behavior is limited. Ethical issues related to control are discussed in Chapter 4.

To achieve its goal of generating knowledge that can be used to describe, understand, predict, and control the world, science needs a way to get there. Value systems reflect traits or characteristics that groups of people hold especially important in achieving their goals. In the United States, for example, people generally value equality of opportunity (versus class structure) and freedom of individual action (versus government control) as ways of achieving the goal of a good society (Rokeach, 1973). Modern Western scientists tend to value four traits or characteristics that lead to the generation of valid knowledge: Science should be empirical, skeptical, tentative, and public. These values are reflected in the way scientists go about their work. When you think about these values, bear in mind that values are ideals, and so are not always enacted—although you should always strive to enact them. Scientists are human, and our human natures occasionally lead us to fall short of our ideals.

Empiricism. The principle of empiricism holds that all decisions about what constitutes knowledge are based on objective evidence rather than ideology or abstract logic; when evidence and ideology conflict, evidence should prevail. As an example, let’s assume you are a school administrator and must choose between two new reading improvement programs, one of which is consistent with your philosophy of education and the other of which is not. In an empirical approach to choosing between the two programs, you set criteria for evaluating the programs, collect information about how well each program meets the criteria, and choose the one that better meets the criteria. In an ideological approach, you choose the one that best fits your philosophy of education, without seeking evidence about how well it works compared to its competitor. In conducting research, scientists seek evidence concerning the correctness or incorrectness of their theories. In the absence of evidence, the scientist withholds judgment.

The principle of empiricism also holds that all evidence must be objective. To be objective, evidence must be collected in a way that minimizes bias, even accidental bias. The rules for conducting research laid out throughout this book explain how to minimize bias.

Skepticism. The principle of skepticism means scientists should always be questioning the quality of the knowledge they have on a topic, asking questions such as, Is there evidence to support this theory or principle? How good is that evidence? Was the research that collected the evidence properly conducted? Is the evidence complete? Have the researchers overlooked any evidence or failed to collect some kinds of evidence bearing on the topic? The purpose of such questions is not to hector the people conducting the research but, rather, to ensure that the theories that describe knowledge are as complete and correct as possible. Consequently, scientists want to see research findings verified before accepting them as correct. This insistence on verification sometimes slows the acceptance of new principles, but it also works to prevent premature acceptance of erroneous results.

Tentativeness. For the scientist, knowledge is tentative and can change as new evidence becomes available. A principle considered correct today may be considered incorrect tomorrow if new evidence appears. This principle grows directly out of the first two: We keep checking the evidence (skepticism), and we give new, valid evidence priority over theory (empiricism). For example, scientists long accepted that the 100 billion neurons in the human brain were fixed at birth and new cells did not grow, but leading researchers, such as Kempermann and Gage (1999), have provided strong evidence to the contrary. These findings were initially highly controversial, but the idea that neurogenesis (the development of new nerve cells) does occur throughout our lifespan has gained widespread acceptance. Exciting new research is exploring the environmental factors, such as physical and mental exercise, that facilitate neurogenesis and the clinical applications of this knowledge, such as the repair of brain damage from stroke, depression or other illnesses (Science Watch, 2005; van Praag, Shubert, Zhao, & Gage, 2005)

Publicness. Finally, science is public. Scientists not only make public what they find in their research, but also make public how they conduct their research. This principle has three beneficial effects. First, conducting research in public lets people use the results of research. Second, it lets scientists check the validity of others’ research by examining how the research was carried out. One reason why research reports in scientific journals have such long Method sections is to present the research procedures in enough detail that other scientists can examine them for possible flaws. Third, it lets other scientists replicate, or repeat, the research to see if they get the same results. The outcomes of all behavioral science research are subject to the influence of random error; sometimes that error works so as to confirm a hypothesis. Because the error is random, replication studies should not get the original results and so should reveal the error. Replication can also help detect instances when scientists are overly optimistic in interpreting their research. One example is the case of the chemists who thought they had fused hydrogen atoms at a low temperature—an impossibility, according to current atomic theory. No one could replicate these results, which were finally attributed to poor research procedures (Rousseau, 1992). We discuss replication research in Chapter 5.

Scientific Approaches to Knowledge

The picture of science presented by the goals and values just described represents the dominant view of what science is and how it is conducted. A set of beliefs about the nature of science (and of knowledge in general) is called an epistemology. The dominant epistemological position in modern Western science is logical positivism. Logical positivism holds that knowledge can best be generated through empirical observation, tightly controlled experiments, and logical analysis of data. It also says that scientists must be disinterested observers of nature who are emotionally distant from what or whom they study, and who generate knowledge for its own sake without concern for whether the knowledge is useful or how it might be used.

A contrasting view of science, especially of the social and behavioral sciences, is the humanistic perspective. The humanistic epistemology holds that science should produce knowledge that serves people, not just knowledge for its own sake; that people are best understood when studied in their natural environments rather than when isolated in laboratories; and that a full understanding of people comes through empathy and intuition rather than logical analysis and “dust bowl empiricism.” Some contrasts between the logical positivist and humanistic epistemologies are summarized in Table 1.1.

An awareness of these differing epistemologies is important for several reasons. First, some of you are epistemological humanists (even though you may not have defined yourselves that way) and so believe that behavioral science research as conducted today can tell you little about people that is useful. Nonetheless, because logical positivism is the dominant epistemology, you should understand its strengths and weaknesses and be able to interpret the results of the research it generates. We personally believe that both approaches to research are useful and mutually reinforcing. As a result, this book goes beyond the laboratory experiment in describing how to do research.

Some Contrasts Between the Logical Positivist and the Humanistic Views of Science

Logical Positivism |

Humanism |

Scientists’ personal beliefs and values have no effect on science. |

Personal beliefs and values strongly affect theory, choice of research topics and methods, and |

|

interpretation of results. |

Knowledge is sought for its own sake; utility is irrelevant. |

Research that does not generate directly applicable knowledge is wasteful. |

Science aims to generate knowledge that applies to all people. |

Science should aim to help people achieve self-determination. |

Phenomena should be studied in isolation, free from the effects of “nuisance” variables. |

Phenomena should be studied in their natural contexts. There are no such things as “nuisance” variables; all variables in the context are relevant. |

Scientific inquiry must be carefully controlled, as in the traditional experiment. |

Science should seek naturalism even at the cost of giving up control. |

A brief, time-limited inquiry is sufficient to generate knowledge. |

Research should be carried out in depth through the use of case studies. |

The scientist should be emotionally distant from the people studied. |

The scientist should be emotionally engaged with the people studied. |

The scientist is the expert and is best able to design and interpret the results of research. |

The research participants are the experts and should be full partners in research that touches their lives. |

There is only one correct interpretation of scientific data |

The same data can be interpreted in many ways. |

Scientific knowledge accurately represents the true state of the world. |

Scientific knowledge represents the aspects and interpretations of the true state of the world that best serve the interests of the status quo. |

The second reason an awareness of these two epistemologies is important is that your epistemology determines your opinions about which theories are valid, what kinds of research questions are important, the best way to carry out research, and the proper interpretation of data (for example, Diesing, 1991). Behavioral scientists vary greatly in epistemological viewpoints (Kimble, 1984; Krasner & Houts, 1984), thus providing ample opportunity to disagree about these issues. Such disagreements are not easily resolved. Personal epistemologies are closely related to culture, personality, and personal background (Mitroff & Kilmann, 1978; Riger, 1992), so individuals tend to see their own epistemologies as the only valid ones.

Finally, an awareness of the humanistic epistemology is important because it is playing a growing role in behavioral science research. Humanistic epistemology plays an important part in feminist theory and critical race theory; both perspectives critique the validity of behavioral science research (for example, Riger, 1992). For example, theorists have questioned whether multiple categories of identity, such as race/ethnicity, gender, social class, and sexuality, should be considered in isolation, as is often the case in behavioral science research. These theorists propose, instead, that more complex research methodologies are needed to understand how the intersectionality of these categories influence social behavior (Cole, 2009). Such questions have implications for all stages of the research process. We will discuss issues raised by these critiques throughout this book.

As noted, the goals of behavioral science include the description, understanding, prediction, and control of behavior. A primary tool that behavioral scientists use to achieve these goals is theory. A theory is a set of statements about relationships between variables. Usually, these variables are abstract concepts (such as memory) rather than concrete objects or concrete attributes of objects (such as the length of a list to be memorized). In a scientific theory, most of the statements have either been verified by research or are potentially verifiable. There are four aspects of theories: their components, their characteristics, their purposes, and criteria for evaluating them.

Chafetz (1978) notes that theories have three components: assumptions, hypothetical constructs and their definitions, and propositions. Let’s examine each.

Assumptions. Theoretical assumptions are beliefs that are taken as given and are usually not subject to empirical testing. Theorists make assumptions for two reasons: Either something cannot be subject to testing, such as assumptions about the nature of reality, or the present state of research technology does not allow something to be tested, such as assumptions about human nature. Assumptions that fall into this second category can, and should, be tested when advances in technology permit. To take an example from biology, Mendel’s theory of heredity postulated the existence of genes, an assumption that technology has only recently allowed to be tested and verified. Theories include three types of assumptions: general scientific assumptions, paradigmatic assumptions, and domain assumptions.

General scientific assumptions deal with the nature of reality. Theorists and scientists in general must assume there is an objective reality that exists separately from individuals’ subjective beliefs; if there were no reality, there would be nothing to study. Science must also assume people can know and understand that reality with reasonable accuracy; if people could not, science would be, by definition, impossible. The development of theory also assumes there is order to reality; that is, events do not happen randomly. A related assumption is that events have causes and it is possible to identify these causes and the processes by which they have their effects. These assumptions are inherently sensible. If you think about it, it would be impossible to conduct one’s daily life without making these assumptions: We assume everyone experiences the same reality that we do and that most events in our lives have causes we can discover, understand, and often control.

Paradigmatic assumptions derive from paradigms, or general ways of conceptualizing and studying the subject matter of a particular scientific field. For example, logical positivism and humanism represent different paradigms for the study of human behavior, the former assuming that objective observation is the best route to valid knowledge, the latter assuming that subjective empathy and intuition represent the best route. Other paradigms in psychology make differing assumptions about human nature (Nye, 1999). Psychoanalytic theory, for example, assumes human nature (as represented by the id) is inherently bad and must be controlled by society; humanism assumes human nature is inherently good and should be free to express itself; and behaviorism assumes human nature is inherently neither good nor bad and that all behavior is shaped by environmental influences. Adherents of different paradigms are often at odds with one another because they are working from different assumptions; because assumptions are usually not testable, these differences cannot be resolved. Even when assumptions are testable, paradigmatic disagreements about how to test them and how to interpret the results of the tests can leave the issue unresolved (for example, Agnew & Pyke, 2007).

Domain assumptions are specific to the domain, or subject, of a theory, such as psychopathology, memory, or work behavior. For example, Locke and Latham (1990) have developed a theory that focuses on the effects performance goals have on the quality of work performance, based on the general proposition that more difficult goals lead to better performance. Their theory makes several explicit assumptions, including the assumptions that most human activity is goal directed, that people are conscious of and think about their goals, and that people’s goals influence how well they perform their work. Domain assumptions are not always explicit. In the domain of sex differences, for example, personality theorists long implicitly assumed that male behavior was the pattern by which all human behavior should be judged; anything that did not fit the male pattern was “deviant” (Katz, 2008). Domain assumptions, especially implicit domain assumptions, often reflect the cultural norms surrounding the subject of the theory and the personal beliefs of the theorist. Consequently they permeate a theory, shaping the content of the theory, the ways in which research on the theory is conducted, and how the results of the research are interpreted. As an example, consider these comments made by a researcher who studied an old-age community:

As a person of a different age and social class, and as a sociologist, my perspective differed from [that of the community residents]. I thought that, as welfare recipients, they were poor; they thought they were “average.” I initially felt that there was something sad about old people living together and that this was a social problem. They did not feel a bit sad about living together as old people, and although they felt that they had problems, they did not think that they were one. (Hochschild, 1973, p. 5)

Because of the problems engendered by implicit assumptions, it is important when reading about a theory to carefully separate aspects of the theory that are based on research, and therefore have evidence to support them, from those based on assumptions, and not to take assumptions as established fact.

Hypothetical Constructs. Theories, as noted, consist of statements about the relationships between variables. The term variable refers to any thing or concept that can take on more than one value. Variables can be concrete in form, such as the size of an object, or they can be abstract concepts, such as personality. The abstract concepts are called hypothetical constructs. Hypothetical constructs are terms invented (that is, constructed) to refer to variables that cannot be directly observed (and may or may not really exist), but are useful because we can attribute observable behaviors to them. The personality trait of hostility, for example, is a hypothetical construct: It cannot be directly observed, but it does represent the concept that people can show consistent patterns of related behaviors. These behaviors—such as cutting remarks, use of physical and verbal coercion, expressed pleasure in the suffering of others, and so forth—can be directly observed. Psychologists therefore invented the term hostility to use in theories of personality to represent whatever inside the person (as opposed to situational factors) is causing these behaviors. However, because we cannot observe hostility directly—only the behaviors attributed to it—we hypothesize that hostility exists, but we cannot demonstrate its existence with certainty.

Kimble (1989) notes that scientists must be careful to avoid two pitfalls that can arise when they use hypothetical constructs. The first is reification: Treating a hypothetical construct as something real rather than as a convenient term for an entity or process whose existence is merely hypothesized, not necessarily known with certainty. It is a fallacy to assume that

if there is a word for [a concept] in the dictionary, a corresponding item of physical or psychological reality must exist, and the major task of science is to discover the a priori meanings of these linguistic givens. On the current psychological scene, this foolish assumption gives rise to ill-conceived attempts to decide what motives, intelligence, personality, and cognition “really are.” (Kimble, 1989, p. 495)

The second pitfall is related to the first. Because hypothetical constructs might not really exist, they cannot be used as explanations for behavior:

If someone says that a man has hallucinations, withdraws from society, lives in his own world, has extremely unusual associations, and reacts without emotion to imaginary catastrophes because he is schizophrenic, it is important to understand that the word because has been misused. The symptomatology defines (diagnoses) schizophrenia. The symptoms and the “cause” are identical. The “explanation” is circular and not an explanation at all. (Kimble, 1989, p. 495)

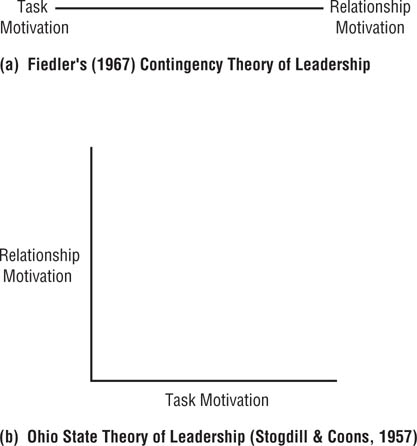

The continued use of a hypothetical construct depends on its usefulness. When a construct is no longer useful as it stands, it will be modified or will be discarded. For example, a popular topic of research in the 1970s was “fear of success,” postulated to be a personality trait that prevented people from doing well because they were predisposed to see success as having negative consequences. Research, however, was unable to validate fear of success as a personality trait. As a result, only limited research continues on this topic (see Mednick & Thomas, 2008, for a brief review). The hypothetical constructs used in theories can be either simple or complex. Simple constructs are composed of only a single component and are referred to as being unidimensional; complex constructs are made up of two or more independent components and are called multidimensional. Let’s examine this distinction by looking at the ways two theories treat the construct of leadership style. Fiedler’s (1967) contingency theory views leadership style as a unidimensional construct: People’s leadership styles vary along a single dimension—Figure 1.1(a). At one end of the dimension are leaders who are task oriented; their main concern is getting the job done. At the other end of the dimension are leaders who are relationship oriented; their main concern is maintaining good relationships among the group members. The unidimensional nature of Fiedler’s conceptualization of the leadership style construct means that a person can score either high on task motivation or high on relationship motivation, but cannot score high on both simultaneously. To score high on one form of motivation, a person must score low on the other: The two styles are mutually exclusive.

The Ohio State theory of leadership (Stogdill & Coons, 1957), in contrast, views task motivation and relationship motivation as independent (uncorrelated) dimensions of leadership style—Figure 1.1(b). Because of this multidimensionality in the Ohio State theory, a person can score high on one dimension and low on the other (as in Fiedler’s theory), but a person could also be conceptualized as being high on both dimensions simultaneously (that is, concerned with both the task and interpersonal relationships) or low on both simultaneously. These differing views on the number of dimensions underlying the construct of leadership style affect how research on leadership is conducted and how leadership training is carried out. For example, research on the Ohio State theory requires that leaders be placed into one of four categories, whereas Fiedler’s theory requires only two. When conducting leadership training, adherents of the two-dimensional view of leadership style aim to train leaders to score high on both dimensions; however, because adherents of the one-dimensional view believe it is impossible to score high on both dimensions simultaneously, they train leaders to make the most effective use of their existing styles (Furnham, 2005).

Unidimensional and Multidimensional Theories of Leadership Style.

Fiedler’s unidimensional contingency theory (a) holds that task motivation and relationship motivation are opposite ends of a single dimension: A person who is high on one must be low on the other. The multidimensional Ohio State theory (b) holds that task motivation and relationship motivation are independent: A person can be high on both, low on both, or high on one and low on the other.

Carver (1989) distinguishes a subcategory of multidimensional constructs that he calls multifaceted constructs. Unlike the dimensions of a multidimensional construct, which are considered independent, those of a multifaceted construct are considered correlated. Because the facets of a multifaceted construct are correlated, the distinctions among facets are sometimes ignored, and the construct is treated as unidimensional. But treating such constructs as unidimensional can lead to mistakes in interpreting research results. For example, if only some facets of a multifaceted construct are related to another variable, the importance of those facets will remain undiscovered. Consider the Type A behavior pattern, which is related to heart disease. The Type A construct includes competitiveness, hostility, impatience, and job involvement. An overall index of Type A behavior composed of people’s scores on these four facets has an average correlation of .14 with the onset of heart disease. However, scores on competitiveness and hostility have average correlations of .20 and .16, respectively, whereas scores on impatience and job involvement have average correlations of only .09 and .03 (Booth-Kewley & Friedman, 1987). The first two facets therefore determine the correlation found for the overall index, but if you just looked at the overall correlation, you would not know that. This situation is analogous to one in which four students work on a group project but only two people do most of the work. Because the outcome is treated as the group’s product, the instructor doesn’t know the relative contributions of the individual group members. We discuss problems related to research with multidimensional and multifaceted constructs in more detail in Chapters 6 and 11.

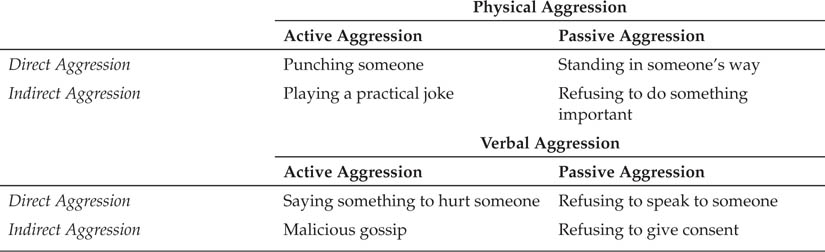

Definitions. An important component of a theory is the definition of its constructs. A theory must carefully define its constructs so that people who use the theory can completely understand the concepts involved. Theories use two types of definitions. The first, narrative definition, explains the meaning of the construct in words. Narrative definitions are similar to dictionary definitions of abstract concepts, but can be much more extensive. For example, Locke and Latham (1990) use almost three pages to explain what their construct of “goal” means and to distinguish it from related terms. Definitions can also take the form of classification systems for multidimensional constructs, laying out the dimensions and the distinctions between the types of behaviors defined by various combinations of dimensions. As an example of the kinds of distinctions that can be made, Buss (1971) identified eight forms of aggression, based on whether the aggression is physical or verbal, active or passive, direct or indirect (see Table 1.2).

Such distinctions are important because different forms of a variable can have different causes, effects, and correlates. Girls, for example, are more likely to experience relational aggressive acts, such as being ignored by friends who are angry with them, whereas boys are more likely to experience physical aggression, such as being hit or shoved (Cullterton- Sen & Crick, 2005).

Because hypothetical constructs are abstract, they cannot be used in research, which is concrete. We therefore must develop concrete representations of hypothetical constructs to use in research; these concrete representations are called operational definitions. A hypothetical construct can have any number of operational definitions. As Table 1.2 shows, aggression can be divided into at least eight categories, each represented by a variety of behaviors. Direct active physical aggression, for example, can be operationalized as physical blows, bursts of unpleasant noise, or electric shocks, and each of these could be further operationalized in terms of number, intensity, or frequency, for a total of at least nine operational definitions. Table 1.2 shows examples of operational definitions of the other forms of aggression. Because operational definitions represent hypothetical constructs in research, they must accurately represent the constructs. The problems involved in developing accurate operational definitions, or measures, of hypothetical constructs are considered in Chapters 6, 9, and 15

Forms of Aggression: The general concept of aggression can be divided into more specific concepts based on whether the aggressive behavior is active or passive, physical or verbal, direct or indirect.

Note: From Buss, 1971, p. 8

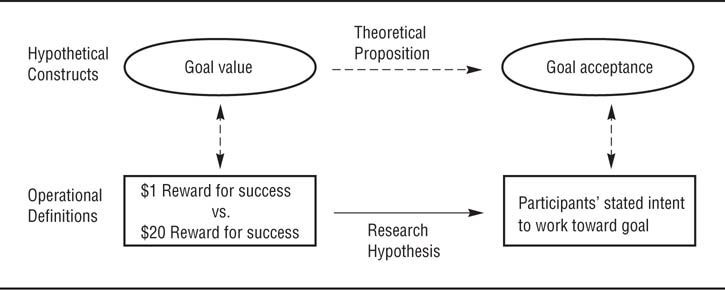

Propositions. As noted, theories consist of statements about relationships among hypothetical constructs; these statements are called propositions. Figure 1.2 shows some of the constructs (rectangles) and propositions (arrows) included in Locke and Latham’s (1990) goal-setting theory of work performance. This part of the theory holds that the more difficult a work goal is, the more value people place on achieving the goal (arrow 1 in Figure 1.2), but (2) more difficult goals also lead people to have lower expectations of achieving the goals. More valued work goals and higher expectations of success at the goals lead to higher levels of goal acceptance (3 and 4). Higher acceptance leads to higher work motivation (5), which combines with ability at the task to affect work performance (6 and 7). Propositions can describe either causal or noncausal relationships. A causal proposition holds that one construct causes another; Figure 1.2, for example, contains the proposition that goal acceptance causes work motivation. Noncausal propositions, in contrast, say two constructs are correlated, but not that one causes the other. Most theoretical propositions are causal.

Just as research cannot deal with hypothetical constructs but uses operational definitions to represent them, research also cannot directly test theoretical propositions but, rather, tests hypotheses about relationships among operational definitions. For example, as Figure 1.3 shows, the proposition that differences in goal value cause differences in goal acceptance (arrow 3 in Figure 1.2) can be operationalized as the hypothesis that people offered $20 for successful completion of a task will be more likely to say that they will work hard to succeed at the task than will people offered $1.

Selected Variables From Locke and Latham’s (1990) Goal-Setting Theory of Work Motivation.

More difficult goals lead to high goal value and lower success expectancies; higher goal value and high success expectancies lead to higher goal acceptance; higher goal acceptance leads to higher motivation; higher motivation combined with higher ability leads to better performance.

Variables can play several roles in theory and research. An independent variable is one that a theory proposes as a cause of another variable. In Figure 1.2, for example, goal difficulty is an independent variable because the theory proposes it as a cause of goal value and expected level of success. A dependent variable is caused by another variable. In the example just given, goal value and expected level of success are dependent variables. Note that the labels “independent” and “dependent” are relative, not absolute: Whether we call a variable independent or dependent depends on its relationship to other variables. In Figure 1.2, work motivation is a dependent variable relative to goal acceptance and an independent variable relative to level of performance.

Theories may include mediating variables, which come between two other variables in a causal chain. In Figure 1.2, work motivation mediates the relationship between goal acceptance and work performance: The theory says goal acceptance causes work motivation, which then causes level of performance. Theories can also include moderating variables, which change or limit the relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable. In Figure 1.2, ability moderates the effect of work motivation on performance; that is, the effect of work motivation on performance differs at different ability levels. As shown in Table 1.3, the theory proposes that there is no effect of work motivation on performance when ability is low (no matter how hard people try, they cannot succeed unless they have a minimum ability level), but when ability is high, high motivation leads to high performance and low motivation leads to low performance (even the most skilled people cannot succeed unless they try).

Relationship Between Theoretical Proposition and Research Hypothesis.

The operational definitions are concrete representations of the theoretical propositions, and the research hypothesis is a concrete representation of the theoretical proposition.

Moderating Effect of Ability on the Relationship Between Work Motivation and Work Performance

Performance level is high only when both ability and motivation are high | ||

|

High Ability |

Low Ability |

High Work Motivation |

High work performance |

Low work performance |

Low Work Motivation |

Low work performance |

Low work performance |

Theories can differ from one another on a variety of characteristics (Bordens & Abbott, 2011); two of them will concern us: how specific a theory is and its scope.

Specification. First, theories can differ on how well they are specified—that is, in how clearly they define their constructs and describe the proposed relationships between them. A well-specified theory can be stated as a list of propositions and corollaries (secondary relationships implied by the propositions), or it can be displayed in a diagram, as in Figure 1.2. A well-specified theory will also explicitly define all the hypothetical constructs included in it. In a poorly specified theory, there can be ambiguity about the meanings of constructs or about how the constructs are supposed to be related to one another. As we will see in later chapters, a poorly specified theory hinders the research process by making it difficult to construct valid measures of hypothetical constructs, derive hypotheses that test the theory, and interpret the research results.

Scope. A second way in which theories differ is in their scope: how much behavior they try to explain. Grand theories, such as psychoanalytic theory, try to explain all human behavior. However, most current psychological theories are narrower in scope, focusing on one aspect of behavior. Locke and Latham’s (1990) theory, for example, deals solely with the determinants of work performance and, even more narrowly, with how work goals affect work performance. Narrow theories such as this do not attempt to deal with all the variables that could possibly affect the behavior they are concerned with; variables not directly involved in the theory are considered to be outside its scope. Figure 1.2, for example, includes only goal acceptance as a cause of work motivation. Many other factors affect work motivation; however, because these factors are not related to work goals, the focus of Locke and Latham’s theory, they are considered to be outside the scope of the theory. These other factors do, however, fall within the scope of other theories.

A term sometimes used interchangeably with theory is model. However, the term model also is used more narrowly to describe the application of a general theoretical perspective to a more specific field of interest. For example, a theory in social psychology called attribution theory (Weiner, 1986) deals with how people interpret events they experience and how these interpretations affect behavior and emotion. The general principles of this theory have been used to develop more specific models of phenomena, such as helping behavior (Wilner & Smith, 2008), academic achievement (Wilson, Daminai, & Shelton, 2002), and clinical depression (Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989), that explain these phenomena in terms of the psychological processes the theory postulates.

Theories serve three scientific purposes: organizing knowledge, extending knowledge, and guiding action. Let’s examine these processes.

Organizing knowledge. The process of organizing knowledge begins with two processes already examined. The first is specifying the scope of the theory—deciding what variables to include. As a theory develops, its scope may widen or narrow—usually the former. For example, Locke and Latham’s (1990) theory at first addressed the relationship of work goals to work performance only, but was later expanded to include job satisfaction and job commitment. Once the scope of a theory is specified, its theorists must define and describe the variables it encompasses.

After theorists specify the scope of their theory and define its variables, they can develop general principles of behavior by identifying the common factors present in a set of observations. These common factors, such as the principle of reinforcement, are usually abstract concepts that represent the more concrete factors and relationships observed. For example, the abstract concept of reward represents such concrete factors as food, water, and praise. Theories then describe the relationships among the abstract concepts; these relationships are inferred, or deduced, from the relationships observed among the concrete behaviors. Thus, the abstract general principle that reward increases the likelihood of behavior is inferred from a set of observations of the relationships between specific concrete rewards and specific behaviors. Theories organize observations made in the course of everyday life as well as observations generated through research. Thus, many of the theories used in applied areas of psychology—such as counseling, clinical, industrial, and educational—originated in the experiences and observations of practitioners in the field.

Extending knowledge. Once a theory is systematically laid out, it can be used to extend knowledge. Theories extend knowledge in three ways. The first is by using research results to modify the theory. When scientists test a theory, the results are seldom in complete accordance with its propositions. Sometimes the results completely contradict the theory; more often, they support some aspects of the theory but not others, or indicate that the theory works well under some conditions but not others. In any such case, the theory must be modified to reflect the research results, although sometimes modifications are not made until the results are verified. Modifications often require adding new variables to the theory to account for the research results.

Theories also extend knowledge by establishing linkages with other theories. As noted, most modern behavioral science theories are circumscribed in their scope: They focus on one aspect of human behavior. However, variables within the scope of one theory often overlap with variables in other theories, thus linking the theories. Such theories essentially comprise a theory of larger scope. For example, Figure 1.4 shows some linkages between the portion of Locke and Latham’s (1990) theory shown in Figure 1.2 and other theories; some of these variables are also included in Locke and Latham’s full theory. Linking theories in this way permits a better understanding of behavior.

Note: Locke and Latham’s variables are shown in rectangles, the others in ovals. From: (a) Bandura, 1982; (b) Hackman & Oldham, 1980; (c) Rusbult & Farrell, 1983; (d) Hollenbeck & Klein, 1987.

Connections Between Variables in Locke and Latham’s (1990) Goal-Setting Theory and Variables in Other Theories.

One can often broaden the scope of a theory by identifying how it overlaps with other theories.

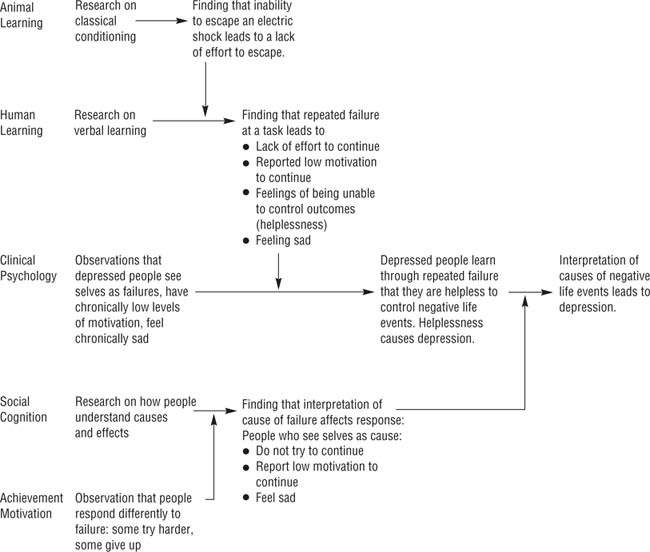

Finally, theories can extend knowledge through the convergence of concepts: Theorists in one field borrow concepts developed from theories in other fields, thus linking knowledge across specialties. This process can be seen in the development of the attributional model of depression (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978), illustrated in Figure 1.5. One origin of the model was in animal research and classical conditioning: Dogs exposed to inescapable electrical shocks eventually gave up trying to escape the shocks, showing a lack of effort to escape (Seligman, 1975). These results were generalized to humans in experiments in verbal learning: Repeated failure at a task led to a lack of effort at the task, and participants reported that they felt little motivation to continue, felt helpless to control their levels of performance, and felt sad about their performance (Seligman, 1975). Seligman pointed out that these outcomes reflected, at a greatly reduced level, symptoms of clinical depression: Depressed people see themselves as failures, have low levels of motivation, and feel chronically sad. Seligman suggested one source of depression might be a feeling he called “learned helplessness,” induced by a series of negative life events or failures.

Convergence of Theories Into Abramson, Seligman, and Teasdale’s (1978) Attributional Model of Depression.

The second origin of the model was in research on achievement motivation and social cognition. Research on achievement motivation found that people respond differently to failure at a task: Some people try harder to succeed at the task the next time they attempt it, whereas others give up. Social cognition researchers study, among other topics, how people understand cause-and-effect relationships in their lives. Their research suggested that differences in response to failure were a result of how people interpreted why they failed: People who see themselves as causing the failure and who see no likelihood of improvement show a lack of effort at the task, report low motivation to continue working at the task, and feel sad (Weiner, 1986). Abramson et al. (1978) suggested that learned helplessness resulted from the way people interpreted negative events in their lives. People who characteristically attribute the causes of negative life events to unchangeable factors within themselves (such as personality) are more likely to become depressed than people who attribute the events to factors outside themselves or who see a likelihood of change. This model therefore took concepts from five different areas of psychology—animal learning, human learning, clinical psychology, social cognition, and achievement motivation—and drew them together into a single model of depression (see Abramson et al., 1989, for a more recent version of the model).

These processes of knowledge extension point out an important characteristic of scientific knowledge: It is cumulative. Scientific knowledge normally grows slowly through the addition of new knowledge from research and theorizing that is grounded in and linked to existing knowledge. As Sir Isaac Newton is said to have remarked several centuries ago, “If I see farther than those who came before me, it is because I stand on the shoulders of giants.” Although scientific knowledge normally grows slowly, sometimes a new theoretical perspective can radically and quickly change the way a field of knowledge conceptualizes its subject matter and the way it carries out research (Kuhn, 1970). For example, Newton and Albert Einstein radically changed the ways in which the scientists of their time viewed the structure and processes of the physical world.

Guiding action. The third purpose of theories is to guide action. Thus, theories of work performance can be used to understand why productivity in a factory is low (perhaps the workers do not accept the work goals) and to devise ways of increasing productivity (perhaps by increasing goal value). The same theory can be used to predict how the level of productivity in a factory would change if changes were made in any of the variables within the scope of the theory, and these predictions could be used to anticipate the consequences of policy changes. However, before we apply theories, we want to be sure their propositions accurately describe the relationships among the variables. This is why we derive hypotheses from theories and test them: We want to ensure our theories are effective before we use them to change people’s behavior or psychological states.

Notice how theories incorporate the four goals of science. Theories define variables and describe the relationships among them. These descriptions of relationships can be used to understand why behaviors occur, to predict what will happen given the degree to which the variables are active in a situation, and to control what happens in a situation by manipulating the levels of the relevant variables.

Criteria for Evaluating Theories

If you were to review the textbooks produced over the past, say, 30 years in any field of behavioral science, you would notice that some theories appear, are influential for a while, but then disappear, whereas others hold up over time. The latter theories are presumably better than the former. What makes a theory good? Shaw and Costanzo (1982) present eight criteria for a good theory, three they consider essential and five that are desirable. Shaw and Costanzo’s three essential criteria are logical consistency, falsifiability, and agreement with known data. Logical consistency simply means that the theory does not contradict itself. We would not, for example, want a theory of memory that says in one place that a particular set of conditions improves memory, and in another place says that the same conditions hurt memory. Fiske (2004) notes that logically consistent theories should also tell a good story; that is, good theories should make sense and be easy to communicate and remember. Falsifiability means you can derive hypotheses that can be examined in research to see if they are incorrect (Popper, 1959). Notice that we test theories to see if they are wrong, not to see if they are correct. It would be impossible to show unequivocally that a theory is true because you could always postulate a set of circumstances under which it might not be true. To prove that a theory is absolutely true, you would have to show that it works for all people under all possible circumstances; such a demonstration would be impossible to carry out. In contrast, one unequivocal demonstration that a hypothesis is incorrect means the theory from which it is derived is incorrect, at least under the conditions of that piece of research. Popper further argued that theories should be tested by risky predictions that have a true chance of being incorrect and that explanations offered after a study’s results are known are not truly scientific. Agreement with known data means the theory can explain data that already exist within the scope of the theory, even if the data were not collected specifically to test the theory. No theory can perfectly account for all relevant data, but the more it does account for, the better it is.

Three desirable characteristics of a theory are clarity, parsimony, and consistency with related theories (Shaw & Costanzo, 1982). A clear theory is well specified: Its definitions of constructs and its propositions are stated unambiguously, and the derivation of research hypotheses is straightforward. If a theory has clear propositions, it is also easy to evaluate against the necessary criteria of logical consistency, falsifiability, and agreement with known data. Parsimony means the theory is not unnecessarily complicated, so that it uses no more constructs and propositions than are absolutely necessary to explain the behavior it encompasses. A parsimonious theory is also likely to be clear. Because most modern behavioral science theories tend to be limited in scope, they should be consistent with related theories. Although a theory that contradicts a related theory is not necessarily wrong (the problem might lie with the other theory), theories that can be easily integrated expand our overall knowledge and understanding of behavior.

It is also desirable for a theory to be useful in the following two ways. First, as Fiske (2004) notes, a theory should be applicable to the real world, helping us solve problems relevant to people’s everyday lives, or should address a problem that social scientists agree is important. For example, psychological theories can help us understand how people acquire information and use it to make decisions (Gilovich, 1991) and they can help engineers design products that are more “user-friendly” (Norman, 1988). Second, a theory should stimulate research, not only basic research to test the theory, but also applied research to put the theory into use, and should inspire new discoveries. Hence, Fiske (2004) notes that good theories are fertile, and “generate scientific fruit … that provoke[s] constructive theoretical debate from opposing perspectives” (p. 135). This inspiration can spring from dislike of as well as adherence to a theory; for example, much current knowledge of the psychology of women comes from research conducted because existing theories did not adequately deal with the realities of women’s lives (Unger, 2001). A good theory, then, branches out and addresses problems related to a many related topics and situations (Fiske, 2004).

Having considered the nature of science and of theory, let us now take an overview of one way in which science and theory come together—in research. The term research can be used in two ways. The way we will use it most often in this book is to refer to empirical research, the process of collecting data by observing behavior. The second way in which research is used is to refer to theoretical or library research, the process of reviewing previous work on a topic in order to develop an empirical research project, draw conclusions from a body of empirical research, or formulate a theory. In Chapter 19, we discuss this form of research. The focus here will be on two topics that are explored in depth in this book: the empirical research process and criteria for evaluating empirical research.

The process of conducting research can be divided into five steps. The first step is developing an idea for research and refining it into a testable hypothesis. As we will see in Chapters 5 and 6, this step involves choosing a broad topic (such as the effect of watching television on children’s behavior), narrowing the topic to a specific hypothesis (such as “Helpful TV characters promote helping behavior in children”), operationally defining hypothetical constructs (“helpful TV characters” and “helping behavior”), and, finally, making a specific prediction about the outcome of the study (“Children who watch a TV episode in which an adult character helps another adult character pick up books dropped by the second adult will be more likely to help a child pick up books dropped by another child than will a child who sees an adult TV character walk past the character who dropped books”). In Chapter 5, we discuss the process of and issues involved in formulating research questions, and in Chapter 6, we discuss operational definition as a measurement process.

The second step in the research process is choosing a research strategy. In Chapter 2, we preview the three main research strategies—case study research, correlational research, and experimental research—and in Chapters 9 through 15, we cover them in depth. The third step is data collection. The data collection process is covered in Chapter 16, and the crucial issue of collecting data ethically is discussed in Chapter 3. Once the data are in, the next step is data analysis and interpreting the results of the analysis. Because this is not a statistics book, we touch on data analysis only occasionally in the context of specific research strategies. However, in Chapters 8 and 16, we discuss some important issues in the meaningful interpretation of research results. Finally, the results of research must be communicated to other researchers and practitioners; in Chapter 20, we cover some aspects of this communication process.

What makes research good? T. D. Cook and Campbell (1979) present four criteria for evaluating the validity of the research or how well behavioral science research is carried out. Construct validity deals with the adequacy of operational definitions: Did the procedures used to concretely represent the hypothetical constructs studied in the research correctly represent those constructs? For example, does a score on a multiple-choice test really represent what we mean by the hypothetical construct of memory? If it does not, can we trust the results of a study of memory that operationally defined the construct in terms of the results of a multiple-choice test? Chapter 6 discusses construct validity in more detail.

Internal validity deals with the degree to which the design of a piece of research ensures that the only possible explanation for the results is the effect of the independent variable. For example, young men tend to score better on standardized math tests, such as the SAT, than do young women. Although one might be tempted to explain this difference in biological terms, research shows that a number of other factors can explain this sex difference, including the nature of the math test, attitudes toward math, and cultural factors that limit or improve opportunity for girls and women (Else-Quest, Hyde, & Linn, 2010). When such factors are allowed to influence research results, that study lacks internal validity. In Chapter 7, we discuss internal validity, and in Chapters 9 through 15, we discuss its application to the research strategies.

Statistical conclusion validity deals with the proper use and interpretation of statistics. Most statistical tests, for example, are based on assumptions about the nature of the data to which they are applied; one such assumption for some tests is that the distribution of the data follows a normal curve. If the assumptions underlying a statistical test are violated, conclusions drawn on the basis of the test could be invalid. In Chapter 17, we discuss some aspects of the interpretation of the outcome of statistical tests.

External validity deals with the question of whether the results of a particular study would hold up under new conditions. For example, if you conducted a study using students at college A as participants and repeated it exactly with students from college B, you would expect to get the same results. If you did, you would have demonstrated one aspect of the external validity of the study: The results hold across samples of college students. There are many aspects to external validity, and it is a controversial topic; in Chapter 8, we discuss it in detail.

Let’s pause for a moment to examine an issue that has been implicit in the discussion up to this point—the issue of the role of inference in psychological research. In conducting research, we observe the relationships between operational definitions of hypothetical constructs and then infer, or draw conclusions about, the nature of the unobservable relationship between the constructs based on the observed relationship between the operational definitions. For example, if you conducted the study on the effect of goal value on goal acceptance illustrated in Figure 1.3, the inferences you would make are shown by the broken lines. You would infer that the operational definitions represent the hypothetical constructs, and if you found that a higher reward led to a stronger stated intent to work toward the goal, you would infer that higher goal value leads to higher goal acceptance. Note that you cannot know with certainty that goal value leads to goal acceptance because you cannot directly observe that relationship; you can only draw the conclusion that goal value leads to goal acceptance because of what you know about the directly observed relationship between the operational definitions.

Scientific knowledge is tentative because it is based on inference; in any piece of research, your inferences might be faulty. In the study illustrated in Figure 1.3, for example, you might erroneously infer that the operational definitions correctly represented your hypothetical constructs when, in fact, they did not (a lack of construct validity). You might erroneously infer that a relationship exists between the two variables being studied when, in fact, there is none (a lack of statistical conclusion validity). You might erroneously infer that reward level was the only possible cause of goal acceptance in the study when, in fact, other possible causes were present (a lack of internal validity). Or, you might erroneously infer that the relationship you observed is true for all situations, not just the one in which you observed it (a lack of external validity). To the extent that you take steps to ensure the validity of your research and verify the results of research, you can have confidence in the conclusions that your theories represent. Nevertheless, you must keep the inferential and tentative nature of psychological knowledge constantly in mind. To do otherwise is to risk overlooking the need to revise theory and practice in the light of new knowledge, thereby perpetuating error.

Theory, Research, and Application

Also implicit in the discussion so far has been the idea that the scientific goals of describing, understanding, predicting, and controlling behavior induce an ineluctable relationship among theory, research, and application in the behavioral sciences. Let us conclude this chapter by summarizing that relationship.

The Interdependence of Theory, Research, and Application

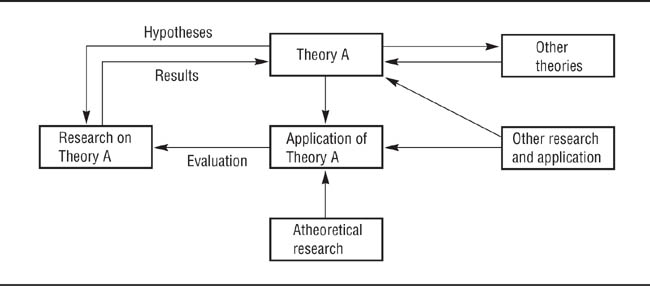

The relationship between theory and research, as shown in Figure 1.6, has two aspects. The deductive aspect derives hypotheses from a theory to test the theory. The inductive aspect uses the results from tests of a theory and from other research to verify the propositions of the theory and modify it as necessary—failures to confirm a theory often suggest refinements and modifications to improve it. Figure 1.6 also shows that related theories can be used to revise, improve, and expand the theory that interests us, just as Locke and Latham’s (1990) theory of work performance ties in with Hackman and Oldham’s (1980) theory of work motivation and Rusbult and Farrell’s (1983) theory of employee turnover (recall Figure 1.4).

Interdependence of Theory, Research, and Application.

Theory directs research and is modified as a result of research and of evaluations of applications of theory. Applications of a theory are also affected by atheoretical research and research based on other theories in the field of application. A theory may also be modified in light of other theories and the results of research on those theories.

The application of behavioral science takes tested theory and puts it to use. Research can evaluate the effectiveness of the application to test how well the theory works in the setting in which it is being applied. For example, Biglan, Mrazek, Carnine, and Flay (2003) describe how scientific research can be applied to the prevention of youth problem behaviors, such as high risk sexual behavior, substance abuse, and low academic achievement. Information gained from such real world applications can also be used to improve the theory; an application failure would indicate that the theory’s utility might be limited to certain situations. Research also can test the validity of assumptions made by practitioners in behavioral science and other fields. The U.S. legal system, for example, makes assumptions about eyewitnesses’ perceptual processes and memory, about how well jurors comprehend judicial instruction, about whether pretrial publicity leads to unfair trials, the efficacy of the persuasive tactics used by attorneys, and about jurors’ individual and group decision-making processes. Research can test the validity of all these assumptions (Brewer & Williams, 2005).

The Uses of Behavioral Science Theory and Research

Dooley (1995) suggests that behavioral science research and theory can be used in three ways: personally, professionally, and politically. The personal use of theory and research is in our own lives. We can, for example, use theory to understand the social world we inhabit: Theories of personality and social behavior can help us understand why people act the way they do, cognitive theories can help us understand why people make decisions we may think are foolish, and lifespan development theories can explain how people grow and change. We can use the scientific perspective to evaluate products and services that people try to persuade us to buy. For example, if a fitness center claims its programs improve psychological as well as physical well-being, the scientific perspective suggests questions we can ask to evaluate the claim of psychological benefit: What evidence supports the claim? How good is the evidence? Is it in the form of well-designed research, or does it consist solely of selected testimonials? Does the design of the research leave room for alternative explanations? If the research participants exercised in groups, did the exercise improve their mental states or did the improvement come because they made new friends in their groups? Asking such questions makes us better consumers.

The professional use of theory and research is its application to behavioral science practice. For example, as shown in Table 1.4, industrial psychology draws on theory and research from a number of other areas of psychology, including cognition, social psychology, motivation, learning, sensation and perception, and psychometrics. Other traditional areas of psychological practice include clinical, counseling, and school psychology, and psychologists have influence in applied areas, such as sports psychology, health education, and the legal system.

The political use of behavioral science involves using research findings to influence public policy. Ever since the landmark Brown v. Board of Education (1954) school desegregation case, the results of behavioral science research have been used to influence court decisions that affect social policy (Acker, 1990). Behavioral science research has also been presented to the U.S. Supreme Court in cases dealing with juror selection in death penalty trials (Bersoff, 1987), employee selection procedures (Bersoff, 1987), challenges to affirmative action in university admissions (American Psychological Association, 2003), and the Graham v. Florida Supreme Court ruling that abolished the death penalty and life sentences without the possibility for parole for juvenile offenders (American Psychological Association, 2009). Research on the problems inherent in eyewitness identification of criminal defendants led the U.S. Department of Justice to issue specific guidelines for questioning eyewitnesses and for the procedures to be used when witnesses are asked to identify a suspect (Wells et al., 2000). In addition, Congress commissioned the Office of Technology Assessment to review psychological research on issues affecting legislation, such as the use of polygraph testing in employee selection (Saxe, Dougherty, & Cross, 1985). The social policies derived from such reviews of research can be no better than the quality of the research on which they are based, so behavioral science research, good or poor, can affect the lives of everyone.

Examples of Applied Issues in Industrial Psychology that are Related to Other Areas of Psychology.

Issue |

Area |

How can equipment be designed to match human information-processing capabilities? |

Cognitive |

How do work groups influence work performance? |

Social |

How can people be motivated to work harder and perform better? |

Motivation |

Are there cultural differences in how people approach tasks in the workplace? |

Cross-cultural |

What is the best way to teach job skills? |

Learning |

What kinds of warning signals are most effective? |

Sensation and Perception |

How can tests be designed to select the most qualified workers? |

Psychometrics |

The goals of science include (a) description, which involves defining phenomena, recording phenomena, and describing relationships between phenomena; (b) understanding, which consists of determining causality in relationships among phenomena; (c) prediction of events both in the real world and in research; and (d) control over phenomena. In determining if a relationship is causal, we look for three conditions: covariation of cause and effect, time precedence of the cause, and no alternative explanations. Science has four key values: (a) empiricism, or the use of objective evidence; (b) skepticism, or taking a critically evaluative viewpoint on evidence; (c) keeping conclusions tentative so that they can be changed on the basis of new evidence; and (d) making the processes and results of science public. There are two contrasting approaches to scientific knowledge: logical positivism and humanism.

Theories consist of assumptions, hypothetical constructs, and propositions. Assumptions are untestable beliefs that underlie theories. They deal with the nature of reality, ways of conceptualizing and studying behavior, and beliefs specific to the various topics studied by the behavioral sciences. Hypothetical constructs are abstract concepts that represent classes of observed behaviors. Theories must carefully define these constructs both conceptually and operationally. Propositions are a theory’s statements about the relationships among the constructs it encompasses. Current theories are usually limited in scope, dealing with a narrow range of variables; they must be well specified, clearly laying out their definitions and propositions. Theories serve three purposes: organizing knowledge, extending knowledge, and guiding action. Three characteristics are necessary for a good theory (logical consistency, testability, and agreement with known data) and five more are desirable (clarity, parsimony, consistency with related theories, applicability to the real world, and stimulation of research).