Research Strategies: An Overview

Chapter Outline

Quantitative and Qualitative Research

Disadvantages of the experimental strategy

Advantages of the case study strategy

Disadvantages of the case study strategy

Use of the case study strategy

Advantages of the correlational strategy

Disadvantages of the correlational strategy

Uses of the correlational strategy

Time Perspectives: Short Term Versus Long Term

Research Settings: Laboratory Versus Field

Research Strategies and Research Settings

Research Settings and Research Participants

Research as a Set of Tradeoffs

Suggestions for Further Readings

Questions for Review and Discussion

In Chapter 1, we examined the nature of science and theory, and the relationships among theory, research, and application. This chapter examines some of the forms research can take. The form a particular piece of research takes can be classified along a number of dimensions. We can classify research in terms of which of three immediate purposes it fulfills—theory testing, applied problem solving, or evaluating the success of an intervention. Research can also be classified in terms of the type of data it produces, quantitative or qualitative. Researchers can collect data by using any of three research strategies experimental, case study, or correlational. Research studies also differ in terms of time perspective (a short-term “snapshot” of behavior or a long-term, longitudinal approach) and where they are conducted (in the laboratory or in natural settings). In this chapter, we review each of these topics to provide a context for the discussion of the foundations of research in Chapters 3 through 6. Many points reviewed here are covered in detail in Chapters 7 through 15.

Research is usually classified into two general categories according to its immediate purpose: basic research, which tests theory in order to formulate general principles of behavior, and applied research, which seeks solutions to specific problems. Evaluation research, conducted to evaluate the success of psychological or social interventions, has become a field in its own right and so can be considered a third category of research. A fourth form, called action research, combines basic, applied, and evaluation research. Let’s examine each of these, looking first at basic and applied research together, because they are so frequently contrasted with one another (Bickman, 1981).

Basic research is conducted to generate knowledge for the sake of knowledge, without being concerned with the immediate usefulness of the knowledge generated. It is usually guided by theories and models and focuses on testing theoretical propositions. In this process of theory testing, even relationships of small magnitude are considered important if they have a bearing on the validity of the theory. Some basic research is also conducted primarily to satisfy the researcher’s curiosity about a phenomenon and may eventually lead to the development of a theory. The results of basic research are expected to be broad in scope and to be applicable, as general principles, to a variety of situations. Basic research tends to use the experimental strategy and to be conducted in laboratory settings, isolating the variables being studied from their natural contexts to gain greater control over them.

Applied research is conducted to find a solution to a problem that is affecting some aspect of society, and its results are intended to be immediately useful in solving the problem, thereby improving the condition of society. Although applied research is frequently guided by theory, it need not be. Its goal is to identify variables that have large impacts on the problems of interest or variables that can be used to predict a particular behavior. As a result, applied research is sometimes narrower in scope than is basic research, focusing on behavior in only one or a few situations rather than on general principles of behavior that would apply to a variety of situations. Applied research tends to be conducted in natural settings and so researchers study variables in context and frequently use the correlational or case study strategies to do so.

Although basic and applied research can be put into sharp contrast, as in the preceding two paragraphs, when you try to apply the labels to a particular piece of research the distinction is not always clear, and trying to make such distinctions might not be useful (Calder, Phillips, & Tybout, 1981). As we will discuss, basic research is often carried out in natural settings and, especially in personality and psychopathology research, makes use of nonexperimental strategies. As noted in the previous chapter, theory can be used to develop solutions to problems, and the adequacy of the solution can test the adequacy of the theory. Through its link to theory, basic research can help improve society—usually considered a goal of applied research. These contributions take two forms (Lassiter & Dudley, 1991). First, and most commonly, basic research can produce a knowledge base for understanding an applied problem. For example, much basic research and theory on helping behavior was triggered by an incident reported in the New York Times in 1964. This article stated that 38 witnesses to Kitty Genovese’s murder did nothing, not even call the police. Although the accuracy of this article has been questioned (Manning, Levine, & Collins, 2007), research inspired by this account resulted in theories and models about the problem of bystander apathy in helping situations; those theories and models suggest a number of ways to increase the likelihood of people helping in both emergency and everyday situations (Piliavin, Dovidio, Gaertner, & Clark, 1981).

Second, basic research and related theory can be used to identify applied problems that might otherwise go unnoticed. Lassiter and Dudley (1991) point to research that applies psychological theory to the use of confessions in criminal trials. Jurors, police investigators, and officers of the court all believe that confessions provide critically important trial evidence. However, a great deal of research shows that people give undue weight to confessions, even when they have reason to discount them (Kassin et al., 2010). Moreover, people generally doubt that confessions are coerced and have difficulty distinguishing between true and false confessions. For example, Kassin, Meissner, and Norwick (2005) videotaped male inmates at a Massachusetts state correctional facility who provided either a true account of the crime for which they were sentenced or a false account of another crime. College students and police officers than reviewed the tapes and indicated which were true accounts. Results showed college students were more accurate than police officers, and accuracy rates were higher when the confession was audiotaped rather than videotaped. Even so, the overall accuracy rate exceeded chance level only when the confession was audiotaped and the raters were college students. Such results are particularly troubling because investigators have also uncovered strong evidence that confessions are fairly easy to coerce and that the overreliance on this source of evidence results in wrongful convictions (Kassin et al., 2010). Through the use of basic research, social scientists have uncovered a bias in the criminal justice system that has profound real world implications.

A great deal of applied behavioral science involves intervention—the use of behavioral science principles to change people’s behavior. In addition, large amounts of public money are spent on social programs designed to enhance the lives of the programs’ clients. Do these interventions and programs work as intended? Evaluation research addresses this question by using a variety of research strategies to assess the impact of interventions and programs on a set of success criteria (see Weiss, 1998). Evaluation research is considered in more detail in Chapter 18.

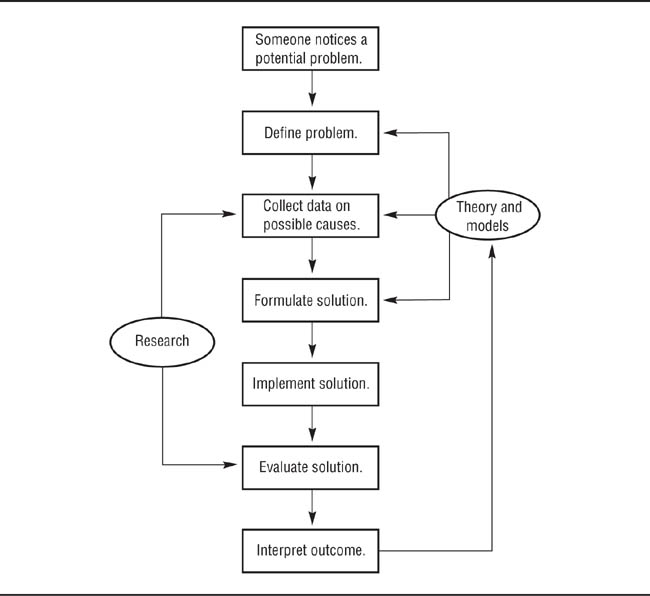

Action research involves the systematic integration of theory, application, and evaluation (Reason & Bradbury, 2001). Action research starts when someone perceives that a problem exists in an applied setting; the study can be initiated by the researcher or an individual directly affected by the problem but, regardless, the research involves a collaboration between these two groups. For example, Bhatt and Tandon (2001) worked with the Lok Jagriti Kendra (LJK) organization to help people in 21 districts in southeastern India regain control over their natural resources. Prior to the collaboration, grassroots efforts in many different villages were attempting to address the issues independently. The researchers used theories of community organization and their understanding of social power, along with their knowledge of forest management, to design a program that addressed the social issues most critical to the tribal members, such as forest protection and land management. The researchers provided a platform for open discussion among the villagers and, as a result, the formerly independent groups united to become one collective organization. The collaboration between researchers and community members led to considerable progress toward the villagers regaining control of their natural resources. For example, the villagers installed wells and irrigation systems that allowed multiple crops to be grown and harvested. In the future, the collaboration might be continued, modified, or replaced in ways that provide additional improvements to the area.

The Action Research Model.

The action research model is diagrammed in Figure 2.1. Notice the integration of theory, application, and research. Bhatt and Tandon (2001) used theories of communication and forest management (based on basic and applied research) to define and develop a potential solution to the villagers’ problem. The potential solution was applied to the problem, resulting in organized efforts that improved water management and crop development. The researchers evaluated the program’s effectiveness and determined that important milestones had been achieved. The results of this study provided information about the validity of both the intervention itself and the theories underlying it. Action research is therefore perhaps the most complete form of science, encompassing all its aspects.

Quantitative and Qualitative Research

Behavioral science data can be classified as quantitative or qualitative. Quantitative data consist of numerical information, such as scores on a test or the frequency with which a behavior occurs. Qualitative data consist of nonnumerical information, such as descriptions of behavior or the content of people’s responses to interview questions. Although any research method can provide quantitative data, qualitative data, or both, the perception exists that some research methods can provide only one type of data (Rabinowitz & Weseen, 1997). For example, experiments are commonly thought of as capable of providing only quantitative data, whereas other research methods, such as case studies, observational studies, and interviews, are often seen as inherently qualitative. This distinction has resulted in a status hierarchy, at least in the United States, in which research that produces quantitative data generally receives more respect than research that produces qualitative data (Maracek, Fine, & Kidder, 1997; Rabinowitz & Weseen, 1997).

A comparison of Table 2.1, which lists some of the characteristics that distinguish quantitative and qualitative research, with Table 1.1, which lists some of the characteristics that distinguish the logical positivist and humanistic views of science, indicates that the quantitative—qualitative distinction is one of philosophy rather than of method. Advocates of the quantitative approach to research tend to follow the logical positivist view of science, whereas advocates of the qualitative approach tend to follow the humanistic view. Adherents of both philosophies strive to understand human behavior but take different routes to achieving that understanding. As Marecek et al. (1997) note, “Many of the distinctions propped up between quantitative and qualitative methods are fictions. As we see it, all researchers—whether they work with numbers or words, in the laboratory, or in the field—must grapple with issues of generalizability, validity, replicability, ethics, audience, and their own subjectivity or bias” (p. 632). Consistent with this view, in this book we have separate chapters on quantitative and qualitative research designs but, throughout the text, we describe both methodologies when appropriate. For example, we describe designs that traditionally utilize quantitative data, such as true experiments (Chapter 9), and field experiments, quasi-experiments, and natural experiments (Chapter 10). We provide an overview of designs that traditionally rely on qualitative data in Chapter 14, and focus on single-case research strategy, a specific example of such designs, in Chapter 13.

Some Contrasts Between the Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches to Research

Quantitative Research |

Qualitative Research |

Focuses on identifying cause-and-effect relationships among variables |

Focuses on understanding how people experience and interpret events in their lives |

The variables to be studied and methods to be used are defined in advance by theories and hypotheses derived from theories and remain unchanged throughout the study |

The variables to be studied and methods to be used emerge from the researcher’s experiences in the research context and are modified as the research situation changes |

To promote objectivity, the researcher keeps a psychological and emotional distance from the process |

The researcher is an inseparable part of the research; the researcher ‘s experiences, not only those research of the research participants, are valuable data |

Frequently studies behavior divorced from its natural context (such as in laboratory research) |

Studies behavior in its natural context and studies the interrelationship of behavior and context |

Frequently studies behavior by manipulating it (as in experiments) |

Studies behavior as it naturally occurs |

Data are numerical—frequencies, means, and so forth |

Data are open-ended—descriptions of behavior, narrative responses to interview questions, and so forth |

Tries to maximize internal validity |

Tries to maximize ecological validity |

Focuses on the average behavior of people in a population |

Focuses on both the similarities and differences in individual experiences and on both the similarities and differences in the ways in which people interpret their experiences |

Note: From Banister, Burman, Parker, Taylor, & Tindall (1994); Marecek, Fine, & Kidder (1997); Stake (1995).

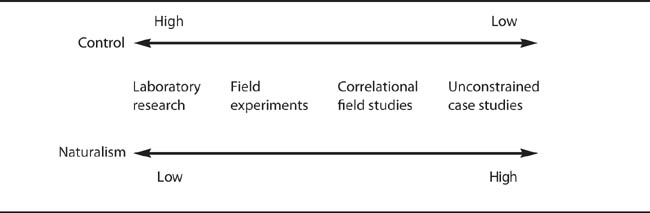

The ways in which research is conducted can be classified into three broad strategies: experimental, correlational, and case study. This section reviews the characteristics of these approaches and discusses some of their major advantages and disadvantages. As you will see, these strategies vary along a continuum that has a high degree of control over the research situation but a low degree of naturalism at one end, and low control but high naturalism at the other end. This review will first cover the strategies that fall at the ends of the continuum (experimental and case study) and contrast those with the middle strategy (correlational). In this chapter the description of these strategies is brief and, perhaps, somewhat oversimplified, to provide a broad overview. In Chapters 9 through 14 we address their complexities and the ways in which they overlap and can be combined.

From the logical positivist point of view, the experiment is the best way to conduct research because only experimentation can determine cause-and-effect relationships. This emphasis on the experiment carries over into the teaching of behavioral science. We informally surveyed nine undergraduate research methods textbooks and found that about three chapters per book were devoted to the experiment in its various forms, compared to half a chapter each for correlational and case study research. Let’s therefore first consider some key characteristics of the experiment so that we can compare it to other research strategies.

Experimentation and causality. Recall the three criteria for determining a cause-and-effect relationship: covariation of proposed cause and effect, time precedence of the proposed use, and absence of alternative explanations for the effect. Although all three strategies let you assess the first two criteria to some degree, only in the classic or “true” experiment can you confidently conclude there are no alternative explanations for the results. The researcher can have this confidence because she or he has taken complete control of the research situation in order to ensure that there can be only one explanation for the results.

Let’s consider a simple experiment in which the researcher hypothesizes that caffeine consumption speeds up reaction time, to see how the researcher exerts this control. First, she controls the setting of the experiment—its physical characteristics (such as the location of the room in which the experiment is conducted, its size, its decor) and time at which it is conducted (such as morning or afternoon) to ensure these are the same for everyone who participates in the experiment. Second, she controls the independent variable, establishing two conditions, an experimental condition in which participants will take a pill containing a standard dose of caffeine and a control condition (or comparison condition) in which participants take a pill containing an inert substance. Both pills are identical in size, shape, color, and weight to ensure that the only difference between the conditions is the caffeine content of the pills. Third, the researcher controls the experimental procedure—what happens during the experiment—so that each participant has exactly the same experience except for the difference in the independent variable based on the condition the participant is in: All participants meet the same experimenter (who does not know which type of pill they will receive), receive the same greeting and instructions, take pills that are identical in appearance, wait the same amount of time after taking the pills, and have the dependent variable (reaction time) measured in the same way—how fast the participant can push a button in response to a signal light. Finally, she controls the characteristics of the participants to ensure that the people who take the caffeine pills and those who take the inert pill are as similar as possible—that their characteristics do not differ systematically across conditions.

Let’s suppose our researcher finds the mean reaction time of the participants who took the caffeine pills was faster than the mean reaction time of the participants who took the inert pills. Can she correctly conclude that the caffeine caused the difference in mean reaction time? The difference itself shows covariation between caffeine consumption and reaction time. The researcher ensured that her participants took their pills before she measured their reaction times, so the potential cause came before the effect. Finally, caffeine was the only aspect of the experiment that differed between the experimental and control conditions, so there are no alternative explanations for the difference in mean reaction times between conditions. That is, nothing else covaried (the first criterion for causality) with reaction time. Because all three criteria for causality have been met, the researcher can correctly conclude that caffeine speeds up reaction time.

Disadvantages of the experimental strategy. The great advantage of the experiment is that it allows us to determine causality; that determination is possible because of the high degree of control the researcher exerts over the research situation. However, that high degree of control also results in a high degree of artificiality so that some behavioral scientists question the extent to which laboratory findings apply to the “real world” (see Argyris, 1980). Let’s consider some of the types of artificiality induced by the controls in our caffeine experiment:

• |

The Setting: Human caffeine consumption (except for that of researchers) rarely takes place in a laboratory in the presence of an experimenter. It is more likely to take place in homes, restaurants, and offices in the presence of family, friends, and coworkers, or alone. |

• |

The Independent Variable: People rarely consume caffeine in the form of pills. Although some over-the-counter stimulants contain high levels of caffeine, most people consume caffeine in the form of coffee, tea, or soft drinks. |

• |

The Procedures: Caffeine consumption rarely occurs under conditions as structured as those in the laboratory. In addition, people in natural settings must respond to visual signals that are frequently much more complex than signal lights, and signals can take other forms, such as sounds. People must also usually respond in ways much more complex than pushing a button. |

• |

The Participants: Not everyone drinks beverages containing caffeine; for those who do, caffeine doesn’t come in a standard dose that is the same for everyone. |

So, then, one might ask, what can this experiment tell us about the effect of drinking coffee alone in the home, or about the ability of a heavy coffee drinker to safely stop a car in response to seeing a collision on the road ahead? Artificiality, as you can see, can be a very vexing problem—discussed in some detail in Chapter 8.

A second disadvantage of the experimental strategy is that it can be used only to study independent variables that can be manipulated, as our researcher manipulated (controlled) the dose of caffeine she administered to her participants. However, it is impossible to manipulate many variables of interest to behavioral scientists. Consider, for example, variables such as age, sex, personality, and personal history. Although we can compare the behavior of people who vary on such factors, we cannot manipulate those factors in the sense of controlling which participant in our research will be older or younger. People come at a given age; we cannot assign people to age group as we can assign them to take a caffeine pill or an inert pill.

The inability to manipulate some variables, such as participant age, is a problem because such variables are often related to a variety of psychological and social variables. For example, older adults are more likely to have tip-of-the-tongue experiences where they are unable to retrieve a word they know well; in contrast, older adults are better at providing word definitions than are younger people (Smith & Earles, 1996). If we find differences between older and younger people on a dependent variable, such psychological and social variables can often provide plausible alternatives to developmental explanations for differences on the dependent variable. For example, older men experience poorer sleep quality than do younger men, but this difference may be explained by an age-linked decline in growth hormone and cortisol secretion (Van Cauter, Leproult, & Plat, 2000). Similar problems exist for gender, personality, and other such “person variables.”

It might also be impossible or prohibitively difficult to study some variables under experimentally controlled conditions. For example, it is theoretically possible to design an experiment in which the size and complexity of an organization would be manipulated as independent variables to study their effects on behavior. However, it would be virtually impossible to carry out such an experiment. Similarly, it is possible to conceive of an experiment to determine the effects of an independent variable that would be unethical to manipulate. To take an extreme example, it would be physically possible to conduct anexperimental study of brain damage in people—assigning some people to have a portion of their brain removed and others to undergo a mock operation—but it would certainly be unethical to do so. More realistically, how ethical would it be to experimentally study the effects of severe levels of stress? We discuss the ethical treatment of research participants in Chapter 3. As we explain in that chapter, in addition to putting limits on experimental manipulations the ethical requirements of research can, under some circumstances, bias the results of the research.

Because of these limitations of the experimental strategy, researchers frequently use the case study or correlational strategies instead of experiments. The next section examines the case study because of the contrast it offers to the experiment.

A case study is an in-depth, usually long-term, examination of a single instance of a phenomenon, for either descriptive or hypothesis-testing purposes (Yin, 2003, 2009). The scope of a case study can range from the anthropologist’s description of an entire culture (Nance, 1975) to the sociologist’s study of a neighborhood or a complex organization (Kanter, 1977; Liebow, 1967), to the psychologist’s study of small-group decision making (Janis, 1972), or an individual’s memory (Neisser, 1981). Although researchers often tend to think of the case study as a tool for description rather than hypothesis testing, case studies can also be used for testing hypotheses (see Chapter 13). The case study can therefore be a very valuable research tool, but it is underused and underappreciated by many behavioral scientists.

Advantages of the case study strategy. A great advantage of the case study is its naturalism. In case studies people are typically studied in their natural environments undergoing the natural experiences of their daily lives. Frequently, the researchers conceal their identities as data collectors, posing as just another person in the setting being studied, so that people’s behavior in the situation is not biased by their knowledge that they are the subjects of research. Case studies are also usually carried out over long periods of time and encompass all the behaviors that occur in the setting, thus affording a great depth of understanding. The other research strategies, in contrast, often focus on one or a limited set of behaviors and use a more restricted time frame. As a result of this naturalism and depth, reports of case study research can give us a subjective “feel” for the situation under study that is frequently lacking in reports of research conducted using the other strategies.

The case study also allows us to investigate rarely occurring phenomena. Because the correlational and experimental strategies are based on the use of relatively large numbers of cases, they cannot be used to study phenomena that occur infrequently. The case study, in contrast, is designed for rare or one-of-a-kind phenomena, such as uncommon psychiatric disorders. Because of the depth at which they study phenomena, case studies can also lead to the discovery of overlooked behaviors. For example, Goodall (1978) observed a group of chimpanzees in the wild kill another group of chimps—a previously unrecorded and unsuspected aspect of chimpanzee behavior unlikely to have been found in other environments (such as zoos) or in short-term studies.

Finally, the case study can allow the scientist to gain a new point of view on a situation—that of the research participant. As noted in Chapter 1, scientists, at least in the logical positivist tradition, are supposed to be detached from their data and to use theory to interpret and to understand their data. A case study, in contrast, can incorporate the participants’ viewpoints on and interpretations of the data, offering new insights. For example, Andersen (1981) revised her theory-based interpretation of data on the psychological well-being of the wives of corporate executives based on her participants’ comments on what they thought made them happy with their lives.

Disadvantages of the case study strategy. The primary disadvantage of the case study strategy is the mirror image of that of the experimental strategy: The case study’s high degree of naturalism means the researcher has very little or no control over the phenomenon being studied or the situation in which the study takes place. Consequently, it is impossible to draw conclusions about causality. Let’s say, for example, that you’re interested in the effect of caffeine on hostility, so you decide to do a case study of a coworker (who happens to be male). Each day you note how much coffee he drinks in the morning, and throughout the day you keep a record of his verbal hostility—yelling, sarcastic comments, and so forth. If your data appear to show a relationship between your coworker’s coffee consumption and his hostility, there are several alternative explanations for the behavior. For example, many things can happen during the workday that can anger a person, and maybe these factors, not the caffeine in the coffee, caused the aggression. Or perhaps it’s a combination of the coffee and these other factors—maybe caffeine doesn’t make him hostile unless something else upsets him.

Another disadvantage of the case study is that you have no way of knowing how typical your results are of other people or situations, or whether your results are unique to the case that you studied. For example, perhaps caffeine is related to hostility only in the person you observed, or only in people with a certain personality type, which happens to be that of your coworker. Or perhaps the relationship is limited to one setting: Your coworker’s caffeine consumption is related to his aggression toward people in the office, but not toward family members or friends. However, because you observe your coworker only in the office, you have no data on the other situations.

A final disadvantage of case study research is that it is highly vulnerable to researcher bias. We discuss this problem in more detail in Chapter 7, but let’s note here that unless controls are imposed to prevent it, researchers’ expectations about what will occur in a situation can affect the data collected (Rosenthal, 1976). For example, in your case study of caffeine and hostility your expectation that higher caffeine consumption leads to more hostility might lead you to pay closer attention to your coworker on days that he drank more coffee than usual or make you more likely to interpret his behavior as hostile on those days.

A striking example of the latter phenomenon comes from the field of anthropology (Critchfield, 1978). Two anthropologists studied the same village in Mexico 17 years apart. Robert Redfield, who conducted his study in the mid-1920s, found life in the village reasonably good and the people open and friendly to one another. Oscar Lewis, who studied the village in the early 1940s, found life there full of suffering and interpersonal strife. Interestingly, Lewis and Redfield agreed that the amount of time that had passed could not have brought about the large amount of change implied by the differences in the results of their studies. What, then, led to the conflicting findings? In Redfield’s opinion,

It must be recognized that the personal interests … of the investigator influence the content of a description of a village…. There are hidden questions behind the two books that have been written about [this village]. The hidden question behind my book is, “What do these people enjoy?” The hidden question behind Dr. Lewis’s book is, “What do these people suffer from?” (quoted in Critchfield, 1978, p. 66)

Uses of the case study strategy. Despite its limitations, the case study, when properly conducted as described in Chapter 13, can be an extremely useful research tool. As we have already noted, the case study is the only research tool available for the study of rarely occurring phenomena, although the researcher must be careful about generalizing from a single case. Sometimes, however, a researcher is not interested in generalizing beyond the case studied. Allport (1961) distinguished between two approaches to the study of human behavior. The nomothetic approach attempts to formulate general principles of behavior that will apply to most people most of the time. This approach uses experimental and correlational research to study the average behavior of large groups of people. However, Allport wrote, any particular individual is only poorly represented by the group average, so the nomothetic approach must be accompanied by an idiographic approach that studies the behavior of individuals. The idiographic approach, of which the case study is an example, addresses the needs of the practitioner, who is not so much interested in how people in general behave as in how a particular client behaves. In meeting this need, Allport (1961) wrote, “Actuarial predictions [based on general principles of behavior] may sometimes help, universal and group norms are useful, but they do not go the whole distance” (p. 21). The idiographic approach goes the rest of the distance by revealing aspects of behavior that get lost in the compilation of group averages.

An important type of behavior that can “get lost in the average” is the single case that contradicts or disconfirms a general principle that is supposed to apply to all people. For example, in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s many psychologists who studied language subscribed to a “motor theory” of speech perception. Essentially, the theory held that people understand speech by matching the sounds they hear with the muscular movements they would use to produce the sounds themselves. Therefore, to understand a speech sound, people must have made the sound themselves (Neisser, 1967). The universality of this theory was disconfirmed by a case study of an 8-year-old child who had never spoken, but who understood what people said to him (Lenneberg, 1962). Case study research is also a fruitful source of hypotheses for more controlled research. If an interesting behavior or relationship is observed in a case study, its generality can be studied in correlational and experimental research, and experimental research can be used to determine its causes and effects. For example, many influential theories of personality, psychopathology, psychotherapy, and organizational behavior were developed using the case study strategy (see Robbins & Judge, 2011; Rychlak, 1981).

The correlational strategy looks for relationships between variables that are consistent across a large number of cases. In an expansion of the caffeine and hostility case study described in the preceding section, you might observe all the workers in an office to determine their levels of coffee consumption and verbal hostility, and compute the correlation coefficient between the variables. As you recall from your statistics classes, the correlation coefficient provides two pieces of information: the strength of the relationship between two variables, indexed from 0 to 1, and the direction of the relationship, positive (when the scores on one variable are high, so are the scores on the other variable) or negative (when the scores on one variable are high, the scores on the other variable are low). You can also determine the statistical significance of the relationship you observed in your sample of office workers—the probability that it occurred by chance.

Because researchers using the correlational strategy merely observe or measure the variables of interest without manipulating them as in the experimental strategy, the correlational strategy is also sometimes called the passive research strategy (see Wampold, 1996). The term passive also recognizes that researchers using this strategy will not always use correlation coefficients or related statistical procedures (such as multiple regression analysis) to analyze their data. For example, comparison of men’s and women’s scores on a variable will usually use the t test or F test because research participants are grouped by sex. Nonetheless, the study would be considered correlational or passive because the researchers could not assign participants to be male or female. Although this distinction is important, we will use the term correlational research strategy because it is still more commonly used to refer to this type of research.

Advantages of the correlational strategy. The correlational strategy has advantages relative to both the case study and the experiment. The case study, as noted, can detect a relationship between two variables within a particular case—for example, a relationship between coffee consumption and hostility for one person. The correlational strategy lets us determine if such a relationship holds up across a number of cases—for example, the relationship between coffee consumption and hostility averaged across all the people working in an office. If the results of a case study and a correlational study are consistent, then we can conclude that the relationship observed in the single case could hold for people in general (although it might hold only for people in that office, as discussed in Chapter 8). If the results of the two studies are inconsistent, we might conclude that the relationship observed in the case study was unique to that individual. As already noted, the correlational strategy also allows for the statistical analysis of data, which the case study does not.

Relative to the experiment, the correlational strategy allows us to test hypotheses that are not amenable to the experimental strategy. Research on personality and psychopathology, for example, can be conducted only using the correlational strategy because it is impossible to manipulate those kinds of variables. Other research, such as that on the effects of brain damage or severe stress on humans, must use the correlational strategy because it would be unethical to manipulate some variables, due to their adverse effects on the research participants.

Disadvantages of the correlational strategy. The correlational strategy shares the major disadvantage of the case study strategy—neither can determine causality. Although the correlational strategy can determine if a dependent variable covaries with an independent variable (as shown by the correlation coefficient), correlational studies are rarely conducted in a way that would establish time precedence of the independent variable and cannot rule out all alternative explanations. Let’s examine these problems using the hypothesis that playing violent video games causes children to become aggressive. Although this hypothesis can be (and has been) tested experimentally (see Anderson et al., 2010), there are potential ethical problems with such experiments. For example, if you really expect playing violent video games to cause children to hurt other people, is it ethical to risk making some children aggressive by assigning them to play those games? However, in day-to-day life some children play more violent video games than do other children, so we can use the correlational strategy to test the hypothesis that there is a positive relationship between playing these games and children’s aggression.

In a typical study, a group of researchers might select a group of children to study, say, those attending a particular public school. The researchers could then ask the children’s parents to list the video games the children play during a given week; these games could be rated for their violence content, which would give each child a score on exposure to violent gaming. Simultaneously, the researchers could have the children’s teachers keep records of the children’s aggressive behavior, providing each child with an aggression score. The researchers could then compute the correlation coefficient between playing violent games and the aggression scores; a recent meta-analysis showed the typical correlation was similar for Eastern and Western cultures and ranged from .20 to .26 for correlational research studies (Anderson et al., 2010).

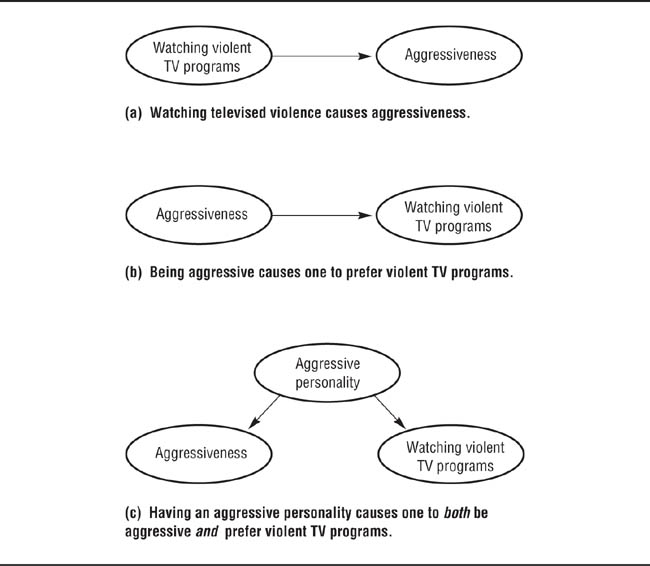

Notice that the study has established covariation between the two variables, but not time precedence: Both variables were measured simultaneously. Consequently, as illustrated in panels (a) and (b) of Figure 2.2, two interpretations of causality are possible: first, that exposure to violent TV programming causes aggression and, second, that children who are already aggressive due to other causes prefer to watch violent TV programs. Because we have no way of knowing which comes before the other—watching violent TV programs or being aggressive—there is no basis for choosing one as the cause and the other as the effect. This problem of not being able to distinguish which variable is the cause is sometimes referred to as reverse causation: The direction of causality might be the reverse of what we hypothesize.

Alternative Explanations for a Correlation Between Watching Violent TV Programs and Aggressiveness.

This situation is further complicated by the possibility of a reciprocal relationship between viewing TV violence and aggression. That is, viewing TV violence might cause children to become aggressive, and this higher level of aggression might, in a circular fashion, induce a greater preference for violent TV programs, which leads to more aggression. Or, of course, it might go the other way: Aggression causes the watching of violent TV programs, which causes more aggression, and so forth. Reverse causation and reciprocal relationships also constitute possible alternatives to violent TV programs as a cause of aggression, so that the study also fails to meet the third criterion for causality.

Another alternative explanation that can never be ruled out in correlational research is known as the third-variable problem. As illustrated in panel (c) of Figure 2.2, some third variable, such as an aggressive personality, might be a cause of both aggression and watching violent TV programs. Because aggression and watching violent TV programs have a cause in common, they are correlated. Let’s illustrate this problem with a concrete example. Assume that you’re visiting the Florida coast during spring break and a storm comes in off the ocean. You notice something from your motel room window, which faces the sea: As the waves come higher and higher on to the beach, the palm trees bend further and further over. That is, the height of the waves and the angle of the palm trees are correlated. Now, are the waves causing the palm trees to bend, or are the bending palm trees pulling the waves higher on to the beach? Neither, of course: The rising waves and the bending trees have a common cause—the wind—that results in a correlation between wave height and tree angle even though neither is causing the other.

As we show in Chapter 11, there are ways of establishing time precedence of the independent variable in correlational research by taking a prospective approach. However, these methods do not eliminate the third-variable problem. Similarly, there are ways of ruling out some alternative explanations for correlational relationships, but to eliminate all the possible alternatives we must know them all and measure them all, which is almost never possible.

Uses of the correlational strategy. If we cannot use the correlational strategy to determine causal relationships, of what use is it? One important use is the disconfirmation of causal hypotheses. Recall that causation requires that there be covariation between the independent and dependent variables; if there is no covariation, there can be no causality. Therefore, a zero correlation between two variables means that neither can be causing the other. This disconfirmational use of the correlational strategy is similar to that of the case study strategy. However, the correlational strategy shows that the disconfirmation holds across a number of people, whereas the case study can speak only to a single instance.

As already noted, the correlational strategy must be used when variables cannot be manipulated. It can also be used to study phenomena in their natural environments while imposing more control over the research situation than is usually done in a case study. For example, the effects of researcher bias can be reduced by collecting data through the use of standardized written questionnaires rather than by direct observation. Although completing the questionnaire intrudes on the research participants’ normal activity, the questionnaire takes some of the subjectivity out of data collection. (The relative advantages and disadvantages of different modes of data collection are discussed in Chapter 16.)

Finally, the correlational research strategy provides an opportunity for the use of the actuarial prediction mentioned by Allport (1961) in his discussion of the idiographic and nomothetic approaches to research. As you may recall from statistics classes, the correlation coefficient not only shows the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables, but can also be used, through the development of a regression equation, to estimate people’s scores on one variable from their scores on another variable. The equation takes the form Y = a + bX, where Y is the predicted score, a is a constant, X is the score being used to predict Y, and b is a multiplier representing how much weight X has in predicting Y. The equation can include more than one predictor variable. For example, at our university you could estimate a student’s undergraduate grade point average (GPA) from the student’s high school GPA and Scholastic Assessment Test (SAT) scores using this equation: College GPA = 1.272 + (.430 x high school GPA) + (.0007 x verbal SAT) + (.0004 x math SAT). Therefore, if you want to choose only those students who were likely to attain a GPA of 2.0, you could enter the applicable high school GPA and SAT scores into the equation and admit only those whose estimated college GPA equaled or exceeded 2.0. Such actuarial predictions are commonly used for employee selection (Cascio & Aguinis, 2011) and can be used in university admission decisions (Goldberg, 1977) and psychiatric diagnosis (Dawes, Faust, & Meehl, 1989). The predictions made by these actuarial methods are, of course, subject to error, but they are generally more accurate than subjective decisions made by individuals or committees working from the data used in the regression equation (Dawes et al., 1989).

Comparing the Strategies

Table 2.2 summarizes the three research strategies by comparing their main advantages, disadvantages, and uses. A key point is that there is no one best research strategy; rather, each is appropriate to different research goals. For example, only the experiment can determine causality, only the case study allows the study of rare phenomena, and only the correlational strategy allows the systematic study of common phenomena that cannot be manipulated. Similarly, each strategy has its disadvantages. For example, the experiment tends to be artificial, neither the correlational strategy nor the case study allows us to determine causality, and the case study does not allow generalization across cases. This issue of competing advantages and disadvantages is discussed at the end of the chapter. First, however, let us look at two other aspects of research: whether or not it examines change over time and whether it is conducted in the laboratory or in a natural setting.

Time Perspectives: Short Term Versus Long Term

Much behavioral science research takes a short-term time perspective, focusing on what happens in a 30- to 60-minute research session. It is, however, often useful to take a longerterm approach, studying how phenomena change over time. Change over time is studied in three contexts: developmental research, prospective research, and the evaluation of intervention outcomes.

The purpose of developmental research is to learn how people change as they move through the life span from birth, through childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, into old age. For example, one might want to know how cognitive processes develop in childhood and how they change over the life span. Three approaches to studying developmental questions are the cross-sectional, longitudinal, and cohort-sequential (Applebaum & McCall, 1983; Baltes, Reese, & Nesselroade, 1977).

Comparison of the Research Strategies

|

Experimental |

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

Uses |

Can determine causality |

Offers low naturalism |

When knowing causality is essential |

Offers quantitative indicators of impact of independent variable |

Some variables cannot be studied | |

|

Case Study |

|

| ||

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

Uses |

Offers high naturalism |

Offers little control; cannot determine causality |

When studying rare phenomena |

Studies phenomena in depth |

Allows low generalizability across cases |

When taking an idiographic approach |

Can study rare phenomena |

Is most vulnerable to researcher bias |

When a source of hypotheses for other strategies is needed |

Is most vulnerable to researcher bias |

|

|

Can discover overlooked behavior |

|

|

Can reveal new points of view |

|

|

Can discover disconfirming cases |

|

|

|

Correlational |

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

Uses |

Can study variables that cannot be manipulated |

Cannot determine causality |

When variables cannot be manipulated |

Offers quantitative indicator of relationship strength |

|

When a balance between naturalism and control is desired |

|

|

When actuarial prediction is desired |

|

|

When it is unethical to manipulate a variable |

|

|

When disconfirmation of a causal hypothesis is desired |

|

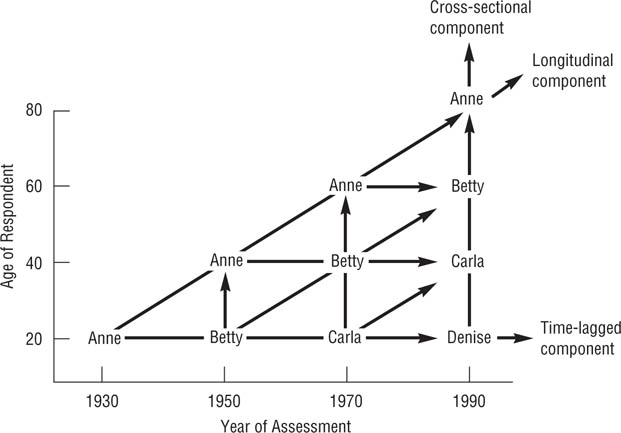

Cross-sectional approach. Cross-sectional research investigates age differences by comparing groups of people who are of different ages. As illustrated in Figure 2.3, a cross-sectional study conducted in 1990 (indicated by the vertical arrow) of age differences among women would compare groups of women who were 80 years old (born in 1910, Anne’s group), 60 years old (born in 1930, Betty’s group), 40 years old (born in 1950, Carla’s group), and 20 years old (born in 1970, Denise’s group). Relative to the other approaches, which follow people across time, cross-sectional research is relatively quick and inexpensive: You find people in the age groups of interest, measure the characteristics of interest, and compare the members of the age groups on those characteristics.

Comparison of Longitudinal and Cross-sectional Research.

Longitudinal research (diagonal arrow) assesses the same people at different ages at different times. Cross-sectional research (vertical row) assesses different people at different ages at the same time.

Notice, however, that although you have assessed age differences, you have not been able to assess developmental trends—how characteristics change over time. You have examined your participants at only one point in their lives, so it is impossible to assess change. You may also have noticed another problem: There is no way to determine whether any differences found among the age groups are due to the chronological ages of the group members (for example, Anne is 80, Denise is 20) or to differences in life experiences (Anne was born in 1910, Denise in 1970). Consider, for example, Anne’s life: She was a child during World War I, a teenager during the Roaring Twenties, a young adult during the Great Depression of the 1930s, and she experienced World War II, the Korean War, the cold war, and the social and political upheavals of the Vietnam War era as a mature adult. Denise has experienced only the 1970s and 1980s, and then only as a child, adolescent, and young adult, not as a mature adult, as did Anne.

The effects of these differences in experience due to time of birth are called cohort effects; a cohort is the group of people born during the same period of time. This period of time may be a month of a particular year, a year, or a period of several years, depending on the focus of the research. Potential cohort effects can lead to a great deal of ambiguity in interpreting the results of cross-sectional research. Let’s say you find differences in cognitive ability among Betty’s, Carla’s, and Denise’s groups. These differences might be due to aging, but they could also be due to cohort-related factors. For example, childhood nutrition affects cognitive ability (Winick, 1979). Betty was a child during the Great Depression, when many children were malnourished; Carla was a child during the 1950s, when children were fed enough, but perhaps not well—there was little of today’s concern with nutrition, and diets were often high in sugar and fats; Denise grew up at a time when parents were more concerned with proper nutrition. These nutritional differences provide a possible alternative to aging as an explanation for group differences in cognitive ability.

Longitudinal approach. Longitudinal research avoids cohort effects by studying the same group of people over time. As shown by the diagonal arrow in Figure 2.3, a researcher (or a research group) could have begun studying Anne’s cohort in 1930, when they were 20 years old, and conducted an assessment every 20 years until 1990. Thus, the longitudinal approach makes it possible to study developmental trends.

The longitudinal approach, however, does have a number of disadvantages. It is, of course, time consuming. Whereas the cross-sectional approach allows you to collect all the data at once, using the longitudinal approach you must wait months, years, or even decades to collect all the data, depending on the number of assessments and the amount of time between them. Multiple assessments increase the costs of data collection, and as time goes by people will drop out of the study. This attrition can come about for many reasons; for example, participants may lose interest in the study and refuse to continue to provide data, or they may move and so cannot be located for later assessments. When dealing with older age groups, people die. Random attrition poses few problems, but if attrition is non- random, the sample will be biased. For example, in an 8-year study of adolescent drug use, Stein, Newcomb, and Bentler (1987) had a 55% attrition rate, due mainly to the researchers’ inability to locate participants after the participants had left high school. However, by comparing the characteristics of their dropouts to those of the participants who completed the research, the researchers concluded that their sample was probably not significantly biased. That is, the characteristics of the participants as assessed at the beginning of the study were not related to whether they dropped out. If, however, only the heaviest drug users when the study began had dropped out, Stein et al. could have applied their results only to a select subgroup of drug users. But Stein et al. could compare the dropouts to the full participants only on the variables they had measured at the outset; attrition could be associated with unmeasured variables and so result in biased findings. Attrition also raises research costs because you must plan for dropouts and start with a sample large enough to provide enough cases for proper data analysis at the end of the research.

Four other potential problems in longitudinal research, all related to the use of multiple assessments, are test sensitization, test reactivity, changes in measurement technology, and history effects. Test sensitization effects occur when participants’ scores on a test are affected by their having taken the test earlier. For example, scores on achievement tests may increase simply because the test takers become more familiar with the questions each time they take the test. Test reactivity effects occur when being asked a question about a behavior affects that behavior. For example, Rubin and Mitchell (1976) found that almost half the college students who had participated in a questionnaire study of dating relationships said that participating had affected their relationships. The questions had started them thinking about aspects of their relationships they had not considered before, either bringing the couple closer together or breaking up the relationship.

Changes in measurement technology occur when research shows one measure is not as valid as originally thought, so it is replaced by a better one. If a longitudinal study used one measure at its outset and a different one later, the researchers face a dilemma: Continued use of the old measure could threaten the validity of their study, but the new measure’s scores will not be comparable to those of the old measure. One solution would be to continue to use the old measure but to add the new measure to the study, drawing what conclusions are possible from the old measure but giving more weight to conclusions based on the new measure during the period of its use.

History effects occur when events external to the research affect the behavior being studied so that you cannot tell whether changes in the behavior found from one assessment to another are due to age changes or to the events. Let’s say, for example, that you are doing a longitudinal study of adolescent illegal drug use similar to Stein et al.’s (1987). As your participants get older, drug use declines. Is this a natural change due to aging, or is it due to some other factor? Perhaps during the course of the study drug enforcement became more effective, driving up the price of illegal drugs and making them less affordable. Over longer periods of time, historical factors that affect one generation (say, people born in 1920) but not another (say, those born in 1970) might limit the degree to which the results of research with one birth year cohort can be applied to another birth year cohort. One way to assess the degree of this cross-generation problem is the cohort-sequential approach to developmental research.

Cohort-sequential approach. Cohort-sequential research combines cross-sectional and longitudinal approaches by starting a new longitudinal cohort each time an assessment is made. For example, as shown in Figure 2.4, Anne’s cohort starts participating in the research in 1930, when they are 20 years old. In 1950, Anne’s cohort (now 40 years old) is assessed for the second time and Betty’s cohort (20 years old) joins the research and is assessed for the first time. This process of adding cohorts continues as the research progresses. As a result, the researcher can make both longitudinal comparisons (along the diagonals in Figure 2.4) and cross-sectional comparisons (along the columns in Figure 2.4). The researcher can also make time-lagged comparisons (along the rows in Figure 2.4) to see how the cohorts differ at the same age. For example, how similar is Anne’s cohort at age 20 (in 1930) to Denise’s cohort at age 20 (in 1990)? Let’s look at an example of research using the cohort-sequential approach, which also shows some limitations of the cross-sectional and longitudinal approaches.

Hagenaars and Cobben (1978) used the cohort-sequential approach to analyze data from Dutch census records for the period 1899 to 1971. They used these data to compute the proportions of women in nine age groups reporting a religious affiliation on eight assessment occasions. We will look at their data for seven cohorts of women at four assessments. Each cohort was born in a different decade, and the data represent cross-sectional assessments made when the women were ages 20–30, 40–50, 60–70, and 80+, and longitudinal assessments at 20-year intervals (1909, 1929, 1949, and 1969). The design is shown in Table 2.3.

Properties of Cohort-sequential Research.

Cohort-sequential research includes both longitudinal and cross-sectional components. It also has a timelagged component (horizontal arrow), assessing different people at the same age at different times.

Design of Hagenaars and Cobben’s (1978) Cohort-Sequential Analysis of Dutch Census Data

Seven cohorts, or groups, of women were assessed at 20-year intervals, beginning when the members of each group were 20 years old. | |||||

|

|

Year of Assessment | |||

Cohort Number |

Decade of Birth |

1909 |

1929 |

1949 |

1969 |

1 |

1819-1829 |

x |

|

|

|

2 |

1839 -1849 |

x |

x |

|

|

3 |

1859-1869 |

x |

x |

x |

|

4 |

1879-1889 |

x |

x |

x |

x |

5 |

1899-1909 |

|

x |

x |

x |

6 |

1919-1929 |

|

|

x |

x |

7 |

1939-1949 |

|

|

|

x |

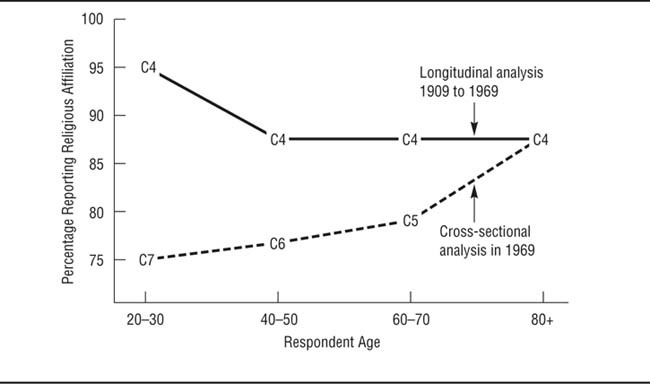

Figure 2.5 shows the results of two approaches to analyzing the data: the longitudinal results for cohort 4 and the cross-sectional results for cohorts 4 through 7 in 1969. Notice the inconsistency: The cross-sectional approach suggests that religious affiliation increases with age, whereas the longitudinal approach suggests that religious affiliation decreases from ages 20–30 to ages 40–50 and thereafter remains stable. Which conclusion is correct? The time-lagged data for cohorts 4 through 7 at ages 20–30, shown in Figure 2.6, suggest an answer: The cohorts entered the research at different levels of religious affiliation, ranging from 95% for cohort 4 to 76% for cohort 7—a cohort effect. As a result, even if the religious affiliation rate of each cohort dropped over time, as suggested by the longitudinal analysis, the older cohorts would always show a higher level of religious affiliation if the amount of change was the same for each cohort.

Results of Longitudinal and Cross-Sectional Analyses of Religious Affiliation Data.

The cross-sectional analysis seems to show an increase of religious affiliation with age, but the longitudinal analysis shows an initial decline followed by a leveling off. (C4, C5, C6, and C7 refer to cohort numbers from Table 2.3.)

Results of Time-Lagged Analysis of Religious Affiliation Data.

This analysis seems to show a linear decrease of religious affiliation with age, in contrast to the analyses in Figure 2.5 (C4, C5, C6, and C7 refer to cohort numbers from Table 2.3).

As you can see, analyzing developmental trends is a complex task. You should undertake it only after a thorough study of the methodologies involved (see Applebaum & McCall, 1983; Baltes et al., 1977). Yet you should be wary of substituting cross-sectional for longitudinal research, as this can lead to erroneous conclusions. Therefore, don’t shy away from longitudinal research because of its complexity: If it is appropriate to answering your research question, learn how to use it and apply it to your question.

Prospective research investigates the relationship between an independent variable at one time and a dependent variable at a later time. This approach can be especially important in correlational research when trying to establish time precedence of an independent variable by showing that the level of the independent variable at time 1 covaries with the level of the dependent variable at time 2. For example, you could examine the correlation between the degree to which people exhibit the Type A behavior pattern (a hypothesized cause of heart disease) and whether they currently have heart disease, but this procedure leaves unanswered the question of whether the behavior came before the illness or the illness came before the behavior. In addition, the most serious cases of heart disease—those that had resulted in death—would not be included in the study. However, if you were to measure Type A behavior in a group of healthy people now and examine their incidence of heart disease over, say, a 10-year period, then you could be certain that the presumed causal factor in the research, Type A behavior, came before the effect, heart disease. You could not, of course, rule out the influence of a third variable that might cause both Type A behavior and heart disease. Prospective research entails many problems of longitudinal developmental research, such as attrition, testing effects, and history effects, which must be taken into account in evaluating the meaning of the research results. Prospective research is discussed again in Chapter 12.

Outcome evaluation, as noted earlier, investigates the effectiveness of a treatment program, such as psychotherapy or an organizational intervention. Outcome evaluations assess participants on a minimum of three occasions: entering treatment, end of treatment, and a follow-up sometime after treatment ends. The entering-treatment versus end-of-treatment comparison assesses the effects of participating in the treatment, and the end-of-treatment versus follow-up comparison assesses the long-term effectiveness of the treatment, how well its effects hold up once treatment has ended. Outcome evaluation research shares the potential problems of attrition, testing effects, and history effects with longitudinal developmental and prospective research. Evaluation research is discussed in more detail in Chapter 18.

Research Settings: Laboratory Versus Field

Research can be conducted in either the laboratory or a natural setting, often called a field setting. The laboratory setting offers the researcher a high degree of control over the research environment, the participants, and the independent and dependent variables, at the cost of being artificial. The field setting offers the researcher naturalism in environment, participants, the treatments participants experience (the independent variable), and the behaviors of participants in response to the treatments (the dependent variable). Let’s briefly consider the relationship between the research strategies, settings, and participants.

Research Strategies and Research Settings

Although we tend to associate certain research strategies with certain settings—for example, the laboratory experiment and the naturalistic case study—any strategy can be used in either setting. Table 2.4 shows these combinations of settings and strategy. It is easy to imagine a case study being conducted in a field setting, but how can one be done in the laboratory? Consider a situation in which a single individual comes to a psychological laboratory to participate in a study. The researcher systematically manipulates an independent variable and takes precise measurements of a dependent variable. Here we have a piece of research that has one of the primary characteristics of a case study—a focus on the behavior of a single individual—but is carried out under the highly controlled conditions of a laboratory setting. Such research is not usually called a case study, however, but a single-case experiment. Both case studies and single-case experiments are discussed in Chapter 13.

Research Strategies and Research Settings

Any strategy can be used in any setting

Research Strategy | |||

|

Single Case |

Correlational |

Experimental |

Field Setting |

Unconstrained case study |

Use of hidden observers |

Field experiment |

Laboratory Setting |

Single-case experiment |

Questionnaire responses |

Traditional experiment |

Experiments can be conducted in field settings as well as in laboratories. In such field experiments, the researcher manipulates an independent variable—a primary characteristic of the experiment—in a natural setting and observes its effect on people in the setting. For example, to see if a helpful model affects helping behavior, you might create a situation in which motorists drive by a disabled vehicle whose driver is or is not being helped by another motorist (the independent variable). Further down the road, they see another disabled vehicle; do they stop to help (the dependent variable)?

Correlational research can be carried out in either setting, with varying degrees of control over what happens in the setting. At one extreme, a researcher could unobtrusively observe natural behaviors in a natural setting to determine the relationship between the behaviors. For example, you could observe natural conversations to see if men or women are more likely to interrupt the person with whom they are talking. The same study could be conducted in a laboratory setting to establish more control over the situation. For example, the researcher might want to control the topic of the conversation and eliminate distractions that might occur in a natural environment.

The combinations of settings and strategies allow for varying degrees of naturalism and control in research. However, as Figure 2.7 shows, these two desirable characteristics of research are, to a large extent, mutually exclusive: More control generally leads to less naturalism, and more naturalism generally leads to less control.

The Tradeoff Between Control and Naturalism in Research.

Combinations of strategies and settings that are more naturalistic generally give the researcher less control over the research situation; combinations that are higher in control also tend to be less naturalistic.

Research Settings and Research Participants

When we design research, we want our results to apply to some target population of people. This target population can be as broad as everyone in the world or as narrow as the workers in a particular job in a particular factory. When we conduct research, it is usually impossible to include everyone in the target population in the research, so we use a participant sample rather than the entire population, and want to apply the results found with the sample to the target population. This process of applying sample-based research results to a target population is one aspect of the problem of generalization in research. Let’s briefly consider the relationship of research settings to participant samples.

Field research is generally carried out in a setting, such as a factory, where a sample of the target population, such as assembly workers, is naturally found. In laboratory research, however, one can either bring a sample of the target population into the laboratory or use a sample from another, perhaps more convenient, population. Much laboratory research is basic research, and most basic research in behavioral science is conducted in academic settings. As a result, most laboratory research in behavioral science that does not deal with special populations (such as psychiatric patients or children) is conducted using college students as participants (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010). Compared to recruiting members of other populations for research, recruitment of college students is convenient (they can be required, within limits, to participate in research) and inexpensive (students participating for class credit are paid nothing, whereas nonstudent research participants usually must be paid for their time). It is also becoming increasing common to recruit research participants on the internet, using chatrooms, listservs, or social networking sites (Krantz & Dalal, 2000); we discuss online research in Chapter 16. However, the results of research conducted with college student or from internet sites participants may not generalize to other populations.

Most field research also uses such convenience samples of participants—whoever happens to be in the setting at the time the research is conducted. Therefore, the results of such research may not generalize across other natural settings or populations (Dipboye & Flanagan, 1979). The results of research conducted in one factory, for example, may not apply to another factory. The only way to ensure broad generalization across settings and populations is to systematically sample from every population and setting of interest, a difficult and expensive process. The nature of the research participants therefore represents another tradeoff in research: the use of college student samples versus convenient samples from specific settings versus participants systematically sampled from all settings and populations. The problems of generalization are discussed in more detail in Chapter 8.

Research as a Set of Tradeoffs

As you have noticed in the discussions of research strategies, time perspectives, and settings, the choice of any one strategy, time perspective, or setting over another results in a tradeoff: Increasing the level of one characteristic essential to good research (such as control) entails decreasing another (such as naturalism). McGrath (1981) notes that researchers would like to be able to maximize three essential characteristics simultaneously in a perfect study: generalizability across populations, precision in the control and measurement of variables, and naturalism. However, tradeoffs among these and other desirable characteristics are inherent in the selection of research strategies, time perspectives, settings, and other decisions that must be made in designing and conducting research. These unavoidable tradeoffs result in what McGrath (1981) considers a basic rule of research: that it is impossible to conduct a perfect study. No one study can provide a conclusive test of a hypothesis; the inherent limitations of the study, resulting from the loss of essential characteristics due to the tradeoffs involved, will always leave questions unanswered. For example, if an independent variable affects a dependent variable in one setting, you could always ask if it would have had the same effect in another setting or using different operational definitions.

What can we do, then, to maximize our confidence in the results of research? We must conduct multiple tests of a hypothesis using different strategies, time perspectives, settings, populations, and measures. The use of multiple studies and different methods serves three purposes. First, the strengths inherent in one method compensate for the inherent weaknesses of another. For example, an effect found under controlled laboratory conditions can be tested in field settings to see if it holds up there or if it is changed by the influence of variables present in the field setting that were controlled in the laboratory.

The second purpose served by multiple studies is verification—the opportunity to learn if a hypothesis can stand up to repeated testing. Finally, using multiple methods allows us to assess the degree of convergence of the studies’ results. The results of any one study might be due to the unique set of circumstances under which that study was conducted; to the extent that the results of multiple studies using different strategies, settings, populations, and so forth converge—are similar—the more confidence we can have that the hypothesis we are testing represents a general principle rather than one limited to a narrow set of circumstances.

Basic research is conducted to establish general principles of behavior, is theory based, and is usually conducted in laboratory settings. Applied research is conducted to solve practical problems and is therefore problem based, and is usually conducted in field settings. Evaluation research is conducted to assess the effectiveness of an intervention, such as psychotherapy. Action research combines the purposes of the other three types. It uses theory to design an intervention to solve a problem defined via applied research; the evaluation of the intervention simultaneously tests the effectiveness of the intervention and the theory on which it is based.

The data produced by research can be either quantitative (numerical) or qualitative (nonnumerical). Although some research methods are thought of as being quantitative and others as being qualitative, any method can provide either, or both, kinds of data. Preference for quantitative or qualitative research reflects the researcher’s philosophy of science.

Three broad strategies are used for conducting research. The experimental strategy emphasizes control and is the only one of the three that can determine causality; however, the high degree of control introduces artificiality into the research context. The case study strategy examines a single instance of a phenomenon in great detail and emphasizes naturalism; however, it cannot be used to determine causality and one cannot generalize across cases. The correlational strategy seeks general relationships across a large number of cases; although it cannot determine causality, it can show that a causal relationship does not exist between two variables and can be used to study variables that are not amenable to the experimental strategy.

Time perspectives affect research design. The longitudinal perspective looks at changes in behavior over time, whereas the cross-sectional perspective focuses on behavior at one point in time. The distinction between these perspectives is especially important in developmental research, which examines how behavior changes with age, because the cross- sectional and longitudinal approaches to data can lead to conflicting conclusions. The cohort-sequential approach allows the examination of possible reasons for those conflicts. The longitudinal perspective is also used in prospective research, which looks at the relationship of an independent variable at one point in time to a dependent variable at a later point in time, and in outcome evaluation.

The two research settings are laboratory and field. Each research strategy can be used in both settings, resulting in different combinations of control and naturalism in research. Different participant populations tend to be used in the two settings, which can limit the generalizability of the results.

Last, the selection of research strategies, time perspectives, settings, and populations can be seen as a tradeoff among three characteristics that are desirable in research: generalizability, control, and naturalism. Maximizing any one of these characteristics in a particular piece of research will minimize one or both of the other two. However, the use of multiple methods across a set of studies allows the strengths of one method to compensate for the weaknesses of others, providing a more solid database for formulating conclusions.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Hoyle, R. H., Harris, M. J., & Judd, C. M. (2002). Research methods in social relations (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

This textbook includes overviews of several topics covered in this chapter, such as basic versus applied research, laboratory versus field research, and qualitative versus quantitative research.

Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (Eds.). (2001). Handbook of action research. London: Sage.