The Ethical Treatment of Research Participantsd

Chapter Outline

Responsibility for Ethical Research

The Institutional Review Board

Criteria for approving research

Ethical Considerations While Planning Research

Ethical objections to deception

Minimizing harm in deception research

How harmful is deception research?

Ethical Obligations During Data Collection

Discovering psychological problems

Ethical Considerations Following Data Collection

Compensation of Control Groups

Data confidentiality and the law

Suggestions for Further Reading

Questions for Review and Discussion

Although the American Psychological Association (APA) was founded in 1892, its membership did not feel a need to establish a code of ethics for psychologists until 1952 and did not establish specific ethical guidelines for research with human participants until 1971 (APA, 1982). Until then, behavioral scientists believed that research participants were sufficiently protected by researchers’ sensitivity to the participants’ well-being (Grisso et al., 1991). However, several studies conducted in the 1960s and early 1970s led to debate about the ethics of invading research participants’ privacy when collecting data (Humphreys, 1975) and of causing harm, especially in the form of severe stress, to research participants (Milgram, 1974). These controversies led the APA to develop its first set of guidelines for research with human participants. Similar concerns over the ethics of biomedical, as well as social and behavioral science, research led to federal regulations concerning research with human participants (U.S. Public Health Service, 1971; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2009). In addition to the ethical guidelines set out in its code of ethics (APA, 2002a), the APA has published a book explaining the guidelines and discussing their implementation (Campbell, Vasquez, Behnke, & Kinscherff, 2009).

This chapter outlines the responsibilities and reviews the guidelines for conducting ethical research. We discuss the guidelines in terms of three phases of a research project: planning the research, collecting the data, and actions following data collection. The guidelines derive from three general ethical principles: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice (National Commission for Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1978). Respect refers to protecting people’s privacy and freedom of choice in deciding whether to participate in research and is reflected in ethical guidelines for voluntary participation in research, informed consent, freedom to withdraw from research, and confidentiality of data. Beneficence refers to protecting research participants from harm and is reflected in ethical guidelines for risk-benefit analysis, avoidance of harm during research, and confidentiality of data. Justice refers to ensuring that the burdens of research participation and the benefits of research are shared by all members of society so that the burdens do not fall unduly on some groups (such as the poor and others with little power) while the benefits accrue only to members of other groups. This principle is reflected in ethical guidelines for voluntary participation and informed consent.

Before beginning this discussion of research ethics, it is important to note that the ethical principles laid out by the APA (2002a) and other professional organizations are guidelines, not rules. That is, they set out broadly defined parameters for behavior intended to cover a wide range of research topics, settings, methods, and participants; they are not rigid sets of do’s and don’ts. Consequently, people will have honest disagreements about the ethical propriety of particular studies. These disagreements are based on personal values, such as those discussed in Chapter 1, and the effects that those values have on judgments about the potential risks to participants posed by the research and about the benefits to be gained from the research by the participants, science, and society.

These differences of opinion surrounded the two studies cited earlier that aroused behavioral scientists’ concern about the ethics of research, and that surround discussion of those studies today. Research continues to stimulate ethical debate. For example, a study of alcoholics (Jacob, Krahn, & Leonard, 1991) raised the question of the ethical propriety of, among other issues, providing alcoholic beverages to alcoholics (Koocher, 1991; Stricker, 1991), leading to further discussion of those issues by the researchers (Jacob & Leonard, 1991) and the editors of the journal that published the research report (Kendall & Beutler, 1991). Because answers to ethical questions are matters of values and judgment, they will never, except in the most extreme cases, be completely resolved. However, these disagreements are beneficial to science because they help keep the importance of conducting ethically sound research in the forefront of researchers’ minds.

Responsibility for Ethical Research

Responsibility for the ethical conduct of research is vested in the researcher and in the institution sponsoring the research. Let’s examine each of these responsibilities.

The ultimate responsibility for the ethical treatment of research participants lies with the person in charge of the research project. Researchers are responsible not only for their own actions, but also for the actions of those who work for them on the research project. These responsibilities place two obligations on researchers. The first is to carefully consider the ethical aspects of the research they design and conduct; the next three sections of this chapter review the ethical guidelines for research. The second obligation is to train students and research assistants in the ethical conduct of research and to monitor their research to ensure it is conducted ethically.

An important aspect of ethical decision making in research is weighing the expected risks of harm presented by participation in the research against the potential benefits of the research to the participants, science, and society. However, researchers can face a conflict of interest in making this risk-benefit analysis. On the one hand, they want to conduct ethical research; on the other, successful completion of the research could enhance their prestige, status within the profession, and sometimes incomes. So researchers, like all people under these circumstances, might inadvertently underestimate the risks of the research and overestimate its benefits. In addition, the researcher might not notice all the potential risks to participants in the research. For these reasons, federal regulations (DHHS, 2009) require institutions that sponsor research with human participants to establish boards to review all research before it is conducted to ensure that the research meets ethical standards. We will discuss these protections as they are implemented in the United States. Ninety-six other countries also have laws or regulations governing research that uses human participants; the Office of Human Research Protections (OHRP) of the DHHS compiles an annual summary of these laws and regulations (OHRP, 2010) if you would like to compare them the DHHS regulations.

The Institutional Review Board

The purpose of the institutional review board (IRB) is to examine proposed research to ensure that it will be carried out ethically. Although federal regulations exempt some types of research from review, most IRBs require proposed research that falls into those categories to be reviewed to ensure that it meets the criteria for exemption.

Membership of the IRB. An IRB consists of at least five members who have varied backgrounds that allow them to review proposed research from diverse viewpoints. They must also be familiar with applicable laws, regulations, and institutional policies. When the research includes members of a population defined by federal regulations as vulnerable to exploitation (such as children and psychiatric patients), the board should also include a member knowledgeable of issues relevant to that population. In addition to its members meeting these knowledge requirements, each IRB must have at least one member who is a scientist, one member who is not a scientist, and one member who is otherwise not affiliated with the institution. Because of these requirements, IRBs often have more than five members. Interestingly, except when the research being reviewed includes prisoners as participants, IRBs are not required to include an advocate for the population with which the research will be conducted. Researchers often find it useful to consult with members of the research population to determine their views of the ethicality of proposed research and their opinions of any potential risks not noticed by the researcher.

Box 3.1 Criteria for Approval of Research by IRBs

1. |

Risks to participants is minimized. |

2. |

Risks to participants are reasonable in relation to anticipated benefits to participants and the importance of the knowledge that can reasonably be expected from the research. |

3. |

Selection of participants is equitable in that members of some populations, such as minority groups, do not bear an inordinate proportion of the risks of the research or receive an inordinately small proportion of expected benefits. |

4. |

Each participant gives informed consent to participate in the research. |

5. |

Informed consent is appropriately documented. |

6. |

The research plan makes adequate provision for monitoring data collection to ensure the safety of participants. |

7. |

There are adequate provisions to protect the privacy of participants and to maintain the confidentiality of data. |

8. |

When some or all of the participants are likely to be vulnerable to coercion or undue influence, safeguards have been included in the study to protect the rights and welfare of the participants. |

Source: Adapted from U.S.DHHS, 2009, sec. 46.111.

Criteria for approving research. Federal regulations establish specific criteria that IRBs must use in deciding whether to approve proposed research. These criteria are shown in Box 3.1 and reflect the ethical guidelines reviewed in this chapter. These are also the only criteria an IRB can use in evaluating the ethical propriety of proposed research. IRBs are,for example, forbidden to consider the ethics of the uses to which the results of the research can be put (DHHS, 2009, sec. 46.111a2). The ethical use of research results is, of course, an important question, addressed in Chapter 4. In addition to their authority to approve or disapprove the initiation of a research project, IRBs are authorized to stop a project if it deviates from the procedures they approved or if it results in unanticipated severe harm to participants.

Box 3.2 Elements of a Research Protocol

1. |

The rationale for the research: Why is it being conducted? |

2. |

The procedures to be used in the research, including |

a. |

The reasons for choosing the participant population to be used and the procedures used to recruit participants. |

b. |

A detailed description of any research apparatus, and its purpose and effects on participants. |

c. |

Copies of any questionnaires that participants are to complete. |

d. |

A detailed description of the participants’ experiences in the research and in the various experimental conditions. |

e. |

Summaries of instructions that participants will receive or transcripts of the instructions if they are used to manipulate the independent variable. |

f. |

If any adverse effects of participation are anticipated, a detailed description of how these effects will be removed or alleviated. |

g. |

If participants are deceived in any way, a detailed description of the procedures to be used to explain the deception to participants and relieve any uneasiness that they feel about it, to include summaries of oral explanations and copies of handouts. |

3. |

A description of the benefits participants can expect to receive from taking part in the research, and the expected benefits of the research for society and science. |

4. |

A description of any anticipated risks to participants, a description of how anticipated risks will be minimized, and a description of the procedures to be followed if the participants suffer harm from the research. If there are any alternative procedures that would present less risk to participants, they must be described and the reasons for not using them explained. |

5. |

A risk-benefit analysis showing that the anticipated benefits of the research outweigh its expected risks. |

6. |

A description of the procedures for obtaining informed consent, including a copy of the consent form if one is required. |

Review procedures. The review process begins when a researcher submits a research protocol to the IRB. The protocol provides the IRB with the information it needs to make its decision and consists of the elements shown in Box 3.2. Depending on the nature of the research and the amount of explanation and description required, the protocol might be very brief or quite long. Once the IRB receives the protocol, its members review it. The IRB may contact the researcher for clarifications during the review process, and the board may call in nonvoting technical experts to evaluate the scientific merit of the proposed research. The board then meets to make its decision. The decision may be to approve the proposal as it is, approve the protocol contingent on specified changes, require that the protocol be amended and submitted for further review, or disapprove the research. Outright disapproval is rare; the board is more likely to require changes to procedures they find to be problematic. When contingent approval is given, the researcher must submit the changes to the IRB and await final approval before beginning the research. The board usually delegates such approval authority to one member, so the process proceeds quickly. Once the IRB approves a protocol, the research must be carried out exactly as described, with no changes, no matter how minor. Any changes must be approved by the IRB; however, minor changes, such as rewording nonessential instructions, usually receive swift approval.

Some types of research are considered to be exempt from IRB review (DHHS, 2009, sec. 46.101b). Examples of exempt research include:

• |

research involving normal educational practices; |

• |

research involving the use of educational tests, surveys, interviews, and observation of public behavior as long as no data that identify individual participants are collected and disclosure of participants’ responses would not put them at risk; |

• |

research involving the use of existing data, such as from data archives; |

• |

taste tests of foods as long as the food does not include additives or includes only additives approved by the Food and Drug Administration. |

Although these types of research are labeled exempt, they still must be reviewed by someone, usually an IRB member or administrator, who verifies that the research meets the exemption criteria.

When developing an IRB protocol, it is useful to discuss it with people who have done similar research to anticipate problems and deal with them in advance. Other experts can also be helpful. For example, a campus physician can give advice about how to effectively screen potential participants for possible health risks involved in the research, such as a history of cardiovascular disease when the research procedures call for strenuous exercise. Finally, members of the IRB can provide advice on how the board as a whole is likely to view a particular research procedure, and many IRBs will give advisory opinions when a researcher is uncertain about the acceptability of a procedure. However, because the vast majority of behavioral research poses little risk to its participants, most protocols face little difficulty in gaining approval.

Ethical Considerations While Planning Research

Four ethical issues must be considered when planning research: the risk of harm or deprivation to participants, voluntary participation in the research, informed consent to participate in the research, and deceiving participants as part of the research.

Risk of Harm or Deprivation

The design of ethical research requires you to consider several categories of risk, to evaluate the severity and likelihood of the possible risk (including the risk of deprivation of benefit as well as the risk of direct harm) and the likely benefits of the research to the participants, science, and society. After evaluating these factors, you must weigh the expected benefits of the research against its anticipated risks. For research to be ethical, the expected benefits must outweigh the anticipated risks.

Categories of risk. When we think about the risk of harm in research, we typically think in terms of physical harm, such as receiving an electrical shock or a side effect of taking a drug. However, as Sieber (1992) points out, there are other types of harm that participants in behavioral research could be exposed to. Perhaps the most common, especially among college students who participate in research, is inconvenience stemming from taking time away from more preferred activities or boredom with the research procedure. Other non-physical risks might be more severe. Psychological harm might result, for example, if a participant is subjected to psychological stress, such as apparently having severely injured another research participant. Although researchers are obligated to remove any such negative effects if they occur, the occurrence itself can have an adverse impact on the participant.

Social harm can result from the disruption of social relationships. For example, Rubin and Mitchell (1976) found that joint participation in a survey on dating relationships by members of dating couples led some of the couples to become less close than they had been before participating in the research, principally through discussing issues included in the survey. Finally, some forms of research might carry risk of economic or legal harm to participants. For example, an employee who, as part of an organizational research project, expresses criticism of the company might be fired if he or she is identified or, in some forms of research, such as on drug abuse, participants might disclose illegal behavior that could result in their arrest if identified. For these reasons, as discussed later, confidentiality is an important part of the researcher-participant relationship.

Evaluating risk. Because harm can accrue to research participants, researchers have the obligation to assess the potential risks to participants in their research and to minimize the risk or not conduct the research if the degree of risk is not justified by the potential benefits of the research. Any research that entails more than minimal risk to participants must be carefully evaluated. As defined by federal regulations, “Minimal risk means that the probability and magnitude of harm or discomfort anticipated in the research are not greater … than those ordinarily encountered in daily life” (DHHS, 2009, sec. 46.102i). Levine (cited in Diener & Crandall, 1978) suggests that the degree of risk to research participants is a function of five factors:

1. |

Likelihood of occurrence. The less probable the harm, the more justifiable is the study. |

2. |

Severity. Minor harm is more justifiable than possible major injuries. |

3. |

Duration after the research. The investigator should determine whether harm, if it does occur, will be short-lived or long-lasting. |

4. |

Reversibility. An important factor is whether the harm can be reversed. |

5. |

Measures for early detection. If incipient damage is recognized early it is less likely that people will be exposed to severe harm. (p. 27) |

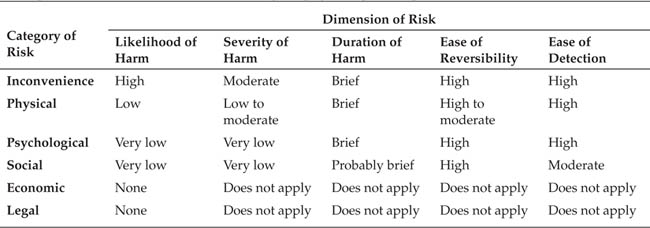

Each of the risk categories identified by Sieber (1992) should be assessed along each of these dimensions, as shown schematically in Table 3.1.

One step that can minimize risk to participants is screening potential participants for risk factors and allowing only those people who are at low risk for harm to participate. For example, Jacob et al. (1991), in their study of the effects of alcohol consumption, took health histories from all their potential participants to eliminate those who might suffer adverse physical reactions to alcohol. When Zimbardo (1973) conducted a study that he anticipated would be stressful, he used psychological screening to weed out potential participants who might be unusually sensitive to stress. Such precautions cannot absolutely guarantee that no harm will come to participants; however, they do reduce the likelihood of harm.

Example Risk Assessment Matrix for a Psychophysiological Experiment

Note: |

For each category of risk the researcher should evaluate the likelihood of harm; the probable severity, duration, and reversibility of the harm; and the ease of detecting that the harm is occurring. The example is for college student participants taking part in an experiment in which their response times to stimuli are recorded while their brain activity is monitored using an electroencephalograph. |

Evaluation of risks involved in research with children requires special consideration because the nature and degree of risk posed by a procedure can change with the ages of the children involved (Thompson, 1990). For example, vulnerability to coercion and manipulation decreases with age, while threats to self-esteem increase with age. It is therefore essential to carefully consider the ages of child research participants when assessing risk. Thompson (1990) and Koocher and Keith-Spiegel (1990) provide excellent guides to this process.

Deprivation as risk. Research that tests the efficacy of a treatment, such as a psychotherapeutic, organizational, or educational intervention, needs a baseline or control condition against which to compare the effects of the treatment. Typically, participants in this control condition receive no treatment, or a placebo treatment that should have no effect on the problem being treated, or a treatment believed to be less effective than the one being tested (Kazdin, 2003). Consequently, the members of the control group are deprived of the benefits the researchers expect to accrue from the treatment being tested. This situation presents a true ethical dilemma because such controls are necessary to accurately assess the effectiveness of the treatment and it would be unethical to put treatments of unknown effectiveness into general use. In effect, members of control conditions in treatment effectiveness research must suffer some deprivation to ensure that only safe and effective treatments are offered to the public.

The degree of risk that members of a control group face depends on the severity of the problem being treated. The risk may be especially high in psychotherapy research, in which participants may be suffering from conditions that hamper their ability to carry on their lives and whose condition may deteriorate, or at least not improve, if left untreated. One solution makes use of the fact that, in many locations, treatment services cannot meet the client demand so that people must be placed on waiting lists for treatment. People on the waiting list are recruited for control groups. Members of such waiting list control groups are deprived of treatment, but it is a deprivation they would have to endure even if no study were being conducted because treatment resources are unavailable. In addition, people in a waiting list control group have the option of not participating in the research or of withdrawing from it. In conducting such studies, researchers must ensure that clients with the most severe problems receive priority for treatment. However, the data from these people should not be used in the research because doing so would lead to a lack of comparability between treatment and control groups. The ethical issues involved in conducting well-controlled treatment effectiveness research are discussed in more detail in Drotar (2008) and Street and Luoma (2002).

Benefits of research. Although participants in behavioral research face risk, they can also benefit from participation. Some research participants receive monetary benefits. These benefits can be direct payments to compensate participants for their time and inconvenience or, in the case of participants in psychotherapy research, reduction or elimination of fees that would otherwise be charged for treatment. Psychological benefits can also accrue. For example, many research participants have reported they had learned something of value about themselves from their experiences (for example, Milgram, 1974; Zimbardo, 1973). Finally, a study can be designed to provide educational benefits to participants when their firsthand experience with research procedures is accompanied by an explanation of how and why the research was conducted.

Risk-benefit analysis. Because research entails both potential risks to participants and potential benefits to participants, science, and society, researchers must carefully consider whether the anticipated benefits of their research justify the anticipated risks to participants. Only when anticipated benefits outweigh anticipated risks is research ethically justified. In much behavioral science research this risk-benefit analysis is not problematic because participants face only minimal risk in the form of short-term inconvenience, even if they can be expected to receive only a small benefit. Sometimes, however, the ethical questions are more difficult. For example, how much harm, say, in the form of severe stress, is justified by the potential to gain scientific or practical knowledge, however great? Remember, before a study is conducted, the value of the knowledge that it will produce is only potential; there is no guarantee it will produce valuable results. Related questions include: Can monetary reimbursement compensate for stress? If so, how many dollars is a particular amount of stress worth?

The resolution of such questions is difficult for a number of reasons (Diener & Crandall, 1978; Sieber, 1992). First, risk-benefit analyses are necessarily subjective. Ethical judgments are value judgments, so perceptions of risk and benefit can vary greatly from person to person. Thus, there is no way to objectively quantify the amount or probability of either the potential risks to participants or the potential benefits of the research. It is therefore impossible to conclusively demonstrate that the anticipated benefits of any piece of proposed research outweigh its anticipated risks. Second, a risk-benefit analysis can deal only with anticipated risks and benefits; unanticipated risks and benefits are always a possibility. Because of this possibility of unanticipated risk, researchers are obligated to monitor participants carefully during the research to detect and avert any developing risks. In addition, as Rubin and Mitchell (1976) found, a study can benefit some participants and harm others. In Rubin and Mitchell’s research, discussion of the questionnaire items led some couples to discover areas of agreement that they had not been aware of, which strengthened their relationships; similar discussions led other couples to discover areas of disagreement, which weakened their relationships. Finally, as noted earlier, risk-benefit analyses can be problematic because the analysis is initially made by the researcher, who may have a conflict of interest in its outcome. Perhaps the best guideline for weighing the risks and benefits of research is one suggested by S. W. Cook (1976): “The conditions of the research should be such that investigators would be willing for members of their own families to take part” (p. 239).

The risk-benefit analysis is designed to protect research participants from harm. The principle of voluntary participation in research is designed to protect potential participants’ autonomy by giving them the choice of whether to participate. This freedom of choice has two aspects: the freedom to decide about participation free from any coercion or excessive inducement and the freedom to withdraw from the research without penalty once it has begun. This section discusses people’s initial decisions to participate in research; freedom to withdraw is discussed later.

Overt coercion. With one exception, people today are rarely dragooned into research participation against their will. The only current situation in which people are given little choice about participating in research resides in the “subject pools” found at many colleges and universities, in which students enrolled in behavioral science courses are required to participate in research as the “subjects” of studies. However, abuses have occurred in the not-so-distant past, especially with prisoners and the mentally ill (Sieber, 1992), leading to very specific ethical guidelines and regulations governing research with members of populations who may have limited power to refuse research participation (DHHS, 2009).

Subject pools are quite common. Sieber and Saks (1989) reported that about 75% of psychology departments with graduate programs have subject pools and that about 95% recruit from introductory courses. The primary justification given for requiring students to participate in research is that research participation, like homework assignments, has educational value: Students get firsthand experience with behavioral science research. Critics of the subject pool system charge that most pools are run solely for the convenience of researchers and that, if educational benefits accrue, they are minimal. As a result, the critics say, the coercive aspects of participation and the resultant limitation of the students’ freedom of choice outweigh the educational benefits (for example, Diener & Crandall, 1978). Because of these concerns, the APA (2002a) has specific guidelines for subject pools that include a requirement for alternatives to research participation that provide the same benefits to students as does participation. Requiring students to participate in research does limit their freedom of choice, so researchers who use subject pools have a strong ethical obligation to make participation as educational as possible. At a minimum, researchers should explain the purpose of the research and how the procedures used will fulfill that purpose, and they should answer participants’ questions about the research.

Discussions of the coerciveness of subject pools are usually based on the opinions of faculty members. What do the students who are required to participate in research think about the process? Surprisingly little research has been conducted on this question. Leak (1981) found that only 2% of the subject pool members he surveyed felt coerced into participating. However, 47% did think that being offered extra credit toward the final course grade was coercive, although only 3% objected to extra credit being given. Leak interpreted these findings as indicating that “some [students] find extra credit a temptation somewhat hard to refuse” (p. 148). Overall, students appear to find research participation a positive and educational experience (Brody, Gluck, & Aragon, 2000). However, because many do not, alternatives must be offered.

Subtle coercion. Alternative assignments must be carefully designed, because if students perceive them to be more aversive than research participation, they represent a subtle form of coercion—research participation becomes the lesser of two evils. Psychological manipulation is another form of subtle coercion that must be avoided. Participants who have completed a study might be reluctant to refuse when asked to “stay a little while longer” and participate in another study, about which they did not know. “Strong encouragement” by an instructor to participate in research might make some students reluctant to use alternative assignments for fear it will adversely impact their grades (Koocher & Keith-Spiegel, 2010). Researchers and teachers are not the only sources of subtle coercion. Reluctant participants may give in to peer pressure to participate (Lidz et al., 1984), and employers may “encourage” employees to participate in research that they favor (Mirvis & Seashore, 1979). Because researchers do not directly control these sources of influence, before collecting data they must ensure that potential participants understand their right to refuse participation.

Excessive inducements. It is quite common and usually ethical to offer people inducements to participate in research —for example, to offer participants money to compensate them for their time and inconvenience. Inducements can become ethically problematic, however, when they are so large that potential research participants feel unable to turn them down and so are effectively coerced into participating. For example, Koocher (1991) and Stricker (1991) thought that Jacob et al.’s (1991) payment of $400 to the families participating in their research might have constituted an offer impossible to refuse. Jacob and Leonard (1991) defended their procedure by pointing out that money was the only inducement they could offer their participants and that the participants gave 75 hours of their time to the research —working out to $5.33 per hour per family, which did not constitute an excessive amount.

The point at which an inducement becomes sufficiently large as to constitute coercion depends on the people to whom it is offered. As noted, Leak (1981) found that college students thought that extra credit for research participation was a coercive inducement. Koocher and Keith-Spiegel (2010) note that $3 per day is a lot of money to prisoners and so might constitute an excessive inducement. The impropriety of large inducements depends largely on the extent to which people feel compelled by their need for the inducement to participate in research that they would otherwise avoid. That is, a large inducement for a study involving severe risk is ethically more questionable than the same inducement for a study presenting minimal risk. Furthermore, people with a strong need for the inducement, such as unemployed people with a need for money, feel the greatest compulsion to participate. It is therefore ethically least proper to offer large inducements to people with great need when the research involves more than minimal risk. However, a large inducement offered to someone not in need might constitute appropriate compensation for the risk. Note that benefits other than money can constitute excessive inducements—for example, a costly service such as psychotherapy or medical care (Koocher & Keith- Spiegel, 2010).

For participation in research to be truly voluntary, potential participants must understand what will happen to them during the research and the risks and benefits of participation. The principle of informed consent requires that potential participants receive this information before data are collected from them so that they can make an informed decision about participation.

Box 3.3 Elements of Informed Consent

1. |

A statement that the study involves research, an explanation of the purpose of the research and the expected duration of the participant’s participation, a description of the procedures to be used, and identification of any procedures that are not standard |

2. |

A description of any reasonably foreseeable risks or discomforts to the participants |

3. |

A description of any benefits to the participant or to others which may reasonably be expected from the research |

4. |

A disclosure of appropriate alternative procedures or courses of treatment, if any, that might be advantageous to the participant |

5. |

A statement describing the extent, if any, to which confidentiality of records identifying the participant will be maintained |

6. |

For research involving more than minimal risk, an explanation as to whether any compensation will be given and an explanation as to whether any medical treatments are available if injury occurs and, if so, what they consist of |

7. |

An explanation of whom to contact for answers to pertinent questions about the research or research participants’ rights, and whom to contact in the event of a research-related injury to the participant |

8. |

A statement that participation is voluntary, that refusal to participate will involve no penalty or loss of benefits to which the participant is otherwise entitled, and that the participant may discontinue participation at any time without penalty or loss of benefits to which the participant is otherwise entitled. |

Source: Adapted from U.S.DHHS, 2009, sec. 46.116.

Elements of informed consent. Federal regulations specify eight basic elements of informed consent, shown in Box 3.3. These regulations also require that, with a few exceptions, researchers obtain participants’ written consent to participate in the form of a consent form. This form must include the information shown in Box 3.3 unless the IRB grants a waiver. The form must be signed by the participant, who has the right to receive a copy of the form. The format of the informed consent form varies from institution to institution; contact your IRB for its format.

An IRB can waive the requirement for written informed consent under limited circumstances, such as when people can give what Sieber (1992) calls behavioral consent, such as hanging up on a telephone interviewer or not returning a mail survey. Under these circumstances, an oral or written statement of the purpose of the research is sufficient to give potential participants the opportunity to indicate consent or refusal behaviorally.

Public behavior. A somewhat controversial exception to the requirement for obtaining informed consent is research consisting solely of observations of public behavior when the identities of the participants are not recorded. There is a presumption that people understand that what they do in public can be observed; consequently, people give implicit consent for others to observe what they do by the fact of doing it publicly. Although this presumption of implicit consent is generally accepted, as shown by its inclusion in federal regulations, not everyone agrees with it. Steininger, Newell, and Garcia (1984), for example, argue that scientific observation of public behavior requires the informed consent of participants because it differs in purpose from casual observation. They take the position that although people do implicitly consent to the observation of their public behavior, they do not implicitly consent to have it recorded, a process that separates scientific observation from casual observation. Steininger et al. hold that recording of behavior without informed consent is an invasion of privacy. Note, however, that federal regulations waive the requirement for informed consent only when no information concerning the identity of the participants is recorded. General descriptive information, such as sex, apparent age, and so forth, is acceptable because it cannot be used to identify a specific individual; the recording of any identifying information, such as an automobile license plate number, requires informed consent.

The ethical issues involved in observing public behavior are complicated by the question of what constitutes a public venue for observation. For example, take Middlemist, Knowles, and Matter’s (1976) study of the effects of personal space invasion on somatic arousal. They conducted their research in public men’s lavatories on a university campus. In one part of their research, they had an observer note which urinals were chosen by users of a lavatory and how far those urinals were from others already in use. The observer also noted how long it took the men to begin urinating (using sound as the indicator) after stepping up to the urinal. Middlemist et al. used the amount of time before urination began as a measure of arousal; somatic arousal tightens the muscles that control urination so that more arousal could lead to longer delays in urination. They hypothesized that closer physical distances between the men at the urinals would lead to greater arousal and so to longer delays in urination. The ethical question this study raises is whether a public lavatory is a sufficiently public place to allow observation of behavior. Koocher (1977) expressed the problem this way: “Though one could claim that a college lavatory is a public place, it is a non sequitur to suggest that one does not expect a degree of privacy there” (p. 121). Middlemist et al. (1977) replied that “the behavior studied was naturally occurring and would have happened in the same way without the observer. The information gathered was available to everyone in the lavatory: the only unusual feature was that the information was recorded” (p. 122). The last point brings us back to Steininger et al.’s (1984) question: Without informed consent, is recording public behavior less ethical than observing it?

Most field research takes place in settings that are unambiguously public and so rarely raises questions on that score. However, much field research also involves experimentation, in which the researcher manipulates the natural situation in order to observe people’s responses to the manipulation. How ethical is it to intervene in a natural setting rather than simply to observe it? Consider another part of Middlemist et al.’s (1976) research, in which they manipulated the distance between an actual user of the urinals in public men’s room and someone working for them who pretended to use another urinal. This confederate used either the urinal directly adjacent to the user’s or one farther away. Again, an observer recorded the amount of time that passes before the user began to urinate. Was it ethical to manipulate personal space in this context and to observe and record the resulting behavior? Middlemist et al. (1977) gave two reasons for concluding that it was. First, they had interviewed half the men they had observed in the first study, telling them what had happened. None reported being bothered by being observed and having their behavior recorded. Second, “the men felt that an invasion of personal space at a urinal was not unusual, had been encountered many times, and was not an experience that caused the, any great pain or embarrassment” (p. 122). The second point reflects a belief held by many researchers that a manipulation that mimics an everyday event presents no ethical problems because it presents minimal risk to participants (Aronson, Ellsworth, Carlsmith, & Gonzales, 1990).

But what about manipulations that go beyond the scope of everyday experiences? For example, is it ethical to present passersby with a man lying on the floor with what appears to be blood spurting from a realistic wound, as did Shotland and Heinold (1985)? Before conducting such studies, you must carefully consider their potential emotional impact on participants and the degree to which any adverse effects can be alleviated after participation. At a minimum, you should anticipate such problems by having your research proposal reviewed by colleagues before the IRB review. It might also be useful to interview people in the population in which the participants will be drawn to determine their opinions about the study’s impact on participants (Sieber, 1992). If the study is carried out, the researcher has a strong ethical obligation to monitor participants’ reactions to the situation and to terminate the study if reactions are more extreme than anticipated.

Competence to give consent. To provide informed consent to participate in research, people must be capable of understanding the risks and benefits involved and realistically evaluating them. However, not all people are capable of understanding these issues and therefore they are not competent to give consent. These groups include children, the mentally ill, the mentally retarded, and people suffering from intellectually incapacitating illness such as Alzheimer’s disease. It is important to note that the law defines child rather broadly in terms of ability to give consent to participation in research: Most states set 18 as the age of consent for this purpose (Annas, Glantz, & Katz, 1977). This legal position has an important implication for researchers who recruit participants from college or university subject pools: Some first-year students might not yet be 18 years old and may therefore not be legally competent to give informed consent.

Meeting the consent requirement for people considered incompetent to give consent is a two-part process. First, the potential participant’s parent or legal guardian must provide informed consent to allow the person to participate. The second process is obtaining the affirmative assent of the potential participant. That is, the person must specifically agree to participate; the only exceptions to this rule are when the participant is incapable of giving assent (as with infants) or when the research provides a direct benefit to the participant in terms of health or well-being. The participants’ assent must be affirmative in that they must specifically agree to participate; “mere failure to object should not … be construed as assent” (DHHS, 2009, sec. 46.402b).

Consent of a parent or guardian and assent of the participant do not relieve researchers of their responsibility for the welfare of participants in their research. In some instances, parents or guardians might not act in the best interest of the participant (Dworkin, 1992; Thompson, 1990). Although probably rare, such problems are most likely to arise when the parent or guardian receives more direct benefit from the research (such as a monetary payment) than does the participant (Diekema, 2005). Researchers must be sensitive to this possibility when designing and conducting their research.

Readability of consent forms. Even when potential participants have the cognitive capacity to give informed consent, researchers do not always provide the required information in a form that lets them understand the research procedures to be used and the attendant risks and benefits. Ogloff and Otto (1991), for example, found that the average consent form used in psychological research was written at the college senior level; even those intended to be used with high school students were written at the college sophomore level. Ogloff and Otto (1991) noted that their findings imply that “to the extent that participants [rely] on consent forms that they ... have ... difficulty reading and comprehending, informed consent [is] not obtained” (p. 249). Not surprisingly, the ability to understand the contents of a consent form decreases as one’s general reading ability decreases (Williams et al., 1995). Researchers have an absolute responsibility to ensure that participants in their research fully understand the procedures, risks, and benefits involved. They must therefore design their consent forms carefully.

Researchers can take a number of steps to increase understanding of their consent forms. First, they can write the forms at an appropriate reading level; some commentators suggest a seventh- or eighth-grade level, even for college students (Young, Hooker, & Freeberg, 1990). Second, researchers can have members of the population from which they will recruit participants read the consent form and comment on its clarity (Ogloff & Otto, 1991). When the research involves greater-than-minimal risk, researchers can supplement the written consent form with an oral explanation and have potential participants explain the contents of the consent form in their own words to ensure understanding (Ogloff & Otto, 1991). Cross-cultural researchers make certain that their terminology can be understood in all cultures studied; to do so, they focus on both conceptual equivalence, which ensures that the terms or phrases used have meaning in those cultures, and linguistic equivalence, which ensures that the informed consent has been correctly translated into the participants’ language (Mio, Barker, & Tumambing, 2012).

Even when the readability of consent forms is not an issue, comprehension might still be problematic. For example, Varnhagen et al. (2005) found that immediately after reading a consent form, a sample of college students recalled an average of only 10% of the information it contained. It can therefore be useful to try to increase participants’ comprehension of the contents of consent forms by having a researcher read the form as the participants read along. The results of research on the comprehension of the elements of informed consent should remind us that informed consent reflects research participants’ states of mind—their comprehension of the risks and benefits of the research; it is not merely a form that they sign. Researchers therefore have an obligation to do all they can to create that state of mind.

Deception is used quite frequently in some areas of behavioral science research; for example, Hertwig and Ortmann (2008) found that about half of the studies published during the late 1990s and early 2000s in major marketing and social psychology journals used some form of deception. Deception can take two forms (Arellano-Goldamos, cited in Schuler, 1982). With active deception, the researcher provides participants with false information. Some of the more common forms of active deception are

• |

Providing false information about the purpose of the research, such as telling participants that an experiment deals with aversive conditioning rather than aggression. |

Providing false information about the nature of the research task, such as telling participants that a personality inventory is an opinion survey. |

|

• |

Using confederates who pose either as other participants in the research or as people who happen to be in the research setting. Not only are the identities of the confederates misrepresented to the participants, but the ways in which they interact with the participants are deceptive in that they are following a script rather than acting naturally. |

• |

Providing participants with false information about their performance, such as by giving them an impossible task in order to induce failure. |

• |

Leading participants to think that they are interacting with another person, who actually does not exist. Communications from the “other person” are actually materials the researcher prepared. |

With passive deception, the researcher either withholds information from the participants or observes or records their behavior without their knowledge. This section addresses the issues of why researchers use deception, the ethical objections to deception, alternatives to deception in research, minimizing harm if deception is used, and whether deception is actually harmful to research participants.

Why researchers use deception. There are several reasons why researchers might include deceptive elements in their studies (Diener & Crandall, 1978; Sieber, 1992). First, participants’ knowledge of the purposes of the research or the procedures that are used could lead them to give artificial responses. Consequently, researchers might withhold the true purpose of the research from participants or give them a false explanation for it. A second reason for using deception, related to the first, is to obtain information participants would be reluctant to give, due to defensiveness or embarrassment, if they knew the true purpose of the research. Use of disguised personality or attitude measures falls into this category. A third reason for the use of deception is to allow manipulation of an independent variable. For example, if a researcher is interested in whether support from another person helps people resist group pressure to change their opinions, at least two deceptions are required to manipulate the independent variable. First, a fictitious group must be constructed that will pressure participants to change their opinions. Second, in the experimental condition, a member of the group must pretend to agree with the participants’ positions and take their side against the group. The researcher will also probably deceive the participants about the purpose of the research, presenting it as studying group interaction rather than response to group pressure. If participants knew the true purpose, that knowledge could affect their responses to the situation.

A fourth reason for deception, related to the third, is to study events that occur only rarely in the natural environment and so are difficult to study outside the laboratory. For example, emergencies, by definition, are rare events, but psychologists are interested in how people respond to them and the factors affecting their responses. It is far more efficient to create a simulated emergency in the laboratory than to hope that a researcher is on the scene and ready to collect data when one occurs naturally. However, as noted in Chapter 2, naturalistic research has advantages over laboratory research and some field research includes experimental manipulations. Therefore, do not avoid field research in favor of laboratory research merely for the sake of convenience.

Finally, deception can be used to minimize the risk of harm to research participants. In studies on conflict and aggression, for example, researchers employ confederates who pose as participants and instigate the conflict or aggression being studied. The confederatesbehave in ways that limit the conflict to non-harmful levels, and they can stop the experiment if the situation appears to be getting out of hand. Such controls would be difficult with two antagonistic real participants.

Ethical objections to deception. Advocates of non-deceptive research hold that deception is in itself unethical and that the expected methodological advantages of deception research are outweighed by its potential harm (for example, Baumrind, 1985). The fundamental position of the advocates of non-deceptive research is that deception is lying and that lying is unethical under most circumstances. They also point to adverse effects that can result from deception. One such effect is that misrepresenting the purposes or procedures of the research limits or eliminates potential participants’ ability to give informed consent: Fully informed consent can come only with full information. All responsible researchers would agree with Sieber (1992) that it is morally indefensible to use deception to trick people into participating in research that they would avoid if they fully understood its purpose and procedures.

Deception may also harm research participants by making them feel foolish for being taken in by it. The use of deception in research might also reduce public trust in behavioral science by making it appear to be one great deception. Furthermore, the use of deception might threaten the validity of research. If research participants believe that deception is commonplace in behavioral science research, they might spend their time trying to deduce the deception (even if there isn’t one) rather than attending to the research task. There is some evidence that such suspiciousness exists, but studies of its effects show no clear pattern of effects on research results (Hertwig & Ortmann, 2008). Finally, public awareness of deception research might lead people to interpret real events as behavioral science experiments; MacCoun and Kerr (1987) describe a real emergency that some bystanders interpreted as an experimental manipulation.

Alternatives to deception. In addition to this ethical critique of deception research, the advocates of non-deceptive research point out that alternative forms of research are available (for example, Sieber, 1992). Research using naturally occurring behaviors in natural settings is one alternative. Simulation research is another alternative. In simulation research (also called active role playing), the researcher designs a laboratory situation that evokes the psychological processes present in a real-life situation (Crano & Brewer, 2002). A classic example from research on bargaining and negotiation is the Acme-Bolt Trucking Game (Deutsch & Krauss, 1960). Participants take the roles of trucking company operators who must maximize profits by making as many deliveries as possible in a given amount of time. They can take either a long or short route to their destinations; however, both participants control gates that can block the other’s short route. Profits are maximized for both participants when they cooperate on access to the short route. Researchers can vary aspects of the situation, such as the amount and type of communication between the participants, to determine their effects on cooperative behavior.

A third, and more controversial, alternative to deception research is passive role-playing (Greenberg & Folger, 1988). In passive role-playing the researcher gives participants a detailed description of a situation, such as a condition of an experiment, and asks them to imagine themselves in the situation and to respond as though they were in the situation. With this procedure, participants can be asked to respond to any kind of situation without risk of harm. Two major criticisms have been leveled against this approach. First, unless participants have actually experienced the situation, their responses are hypothetical, and research has shown that hypothetical responses bear little relation to people’s responses in the actual situation. The second criticism is that role playing cannot consistently replicate the results of deception research; sometimes it does and sometimes it doesn’t. As discussed in Chapter 5, these failures to replicate do not invalidate either methodology, but raise the as yet unanswered question of which methodology provides more valid data. Despite the controversy over whether passive role playing can substitute for deception in research, it does have two important uses. First, it can be used to assess the ways in which participants will interpret an experimental situation (Crano & Brewer, 2002; Greenberg & Folger, 1988). Researchers can give participants a detailed description of a situation and ask them to comment on its realism and believability. Second, participants can role-play a situation and comment on its ethical components, such as any aspects they would find disturbing (Sieber, 1992).

Consent to deception. Some commentators have suggested that one way to resolve the conflict between informed consent and deception is to obtain potential participants’ consent to be deceived. Several approaches to this process have been suggested. When participants are recruited from a subject pool, a general announcement can be made that some experiments will include deception and that signing up for an experiment gives permission for deception to be used. Anyone not willing to participate under these conditions would be allowed to do alternate assignments (D. T. Campbell, 1969a). One drawback to this approach is that it denies students the opportunity to participate in non-deceptive research if they wish to. Alternatively, students could be asked to sign up for various categories of research, one of which is studies including deception; participants for deception research would be recruited only from this roster (Milgram, 1977). In any research situation, the consent form can inform potential participants that the research might entail deception. In this case, participants would give consent to be deceived (Sieber, 1992). In any of these cases, researchers have a special obligation that any deception used entail the minimum possible risk to participants.

Minimizing harm in deception research. The APA (2002a) has the following policy regarding the use of deception in research:

(a) |

Psychologists do not conduct a study involving deception unless they have determined that the use of deceptive techniques is justified by the study’s significant prospective value and that effective nondeceptive alternative procedures are not feasible. |

(b) |

Psychologists do not deceive prospective [research] participants about research that is reasonably expected to cause physical pain or severe emotional distress. |

(c) |

Psychologists explain any deception that is an integral feature of … an experiment to participants as early as is feasible, preferably at the start of their participation, … and permit participants to withdraw their data. (p. 1070) |

This policy implies that researchers who are considering using deception in research should ask themselves six questions (Diener & Crandall, 1978; Sieber, 1992):

When the research involves children, give careful consideration to the highly impressionable nature of young children and the effects deception can have on them. Koocher and Keith-Spiegel (1990, pp. 133-142) present an excellent outline of this issue. An important safeguard is to provide parents or guardians with complete information about any deception that will be used before they given consent for their children to participate (Fisher, 2005).

How harmful is deception research? One ethical criticism of deception research is that it harms participants by attacking their self-esteem and by making them feel used and foolish (Hertwig & Ortmann, 2008). However, research conducted with former participants in deception research provides mixed support for this position (Christensen, 1988). Former participants generally don’t think they have been harmed and say that although deception is undesirable, they understand and accept its necessity once it has been explained. On the whole, college students (who are the majority of participants in behavioral science research that uses deception) see deception research as being less ethically problematic than do researchers. Nonetheless, it is important to bear in mind that the results of the research reviewed by Christensen reflect the average response of groups of people; specific individuals may still have very strong feelings about being deceived. Also, some forms of deception are seen as more reprehensible than others (Hertwig & Ortmann, 2008). For example, people always want to be informed if they are going to be asked about aspects of their lives they consider to be private, such as sexual behavior.

Ethical Considerations During Data Collection

The researcher’s ethical obligations continue when participants agree to take part in the study. Our most basic obligation as researchers is to treat participants with courtesy and respect. We must never lose sight of the fact that the vast majority of research participants receive no monetary compensation and so are doing us a favor by participating in our research. Their kindness should be reciprocated by kindness on our part. Let’s examine two other, more complex, ethical obligations in detail: avoidance of harm and honoring retractions of consent.

In some research, the design of the study poses risks to participants that must be monitored to ensure that they do not become excessive, but even research designed to pose minimal risk can have unexpected adverse effects. Researchers therefore have an obligation to screen potential participants for known risk factors, allowing only those at low risk to participate. They must also monitor participants during the research for signs of unanticipated negative effects. A more difficult problem arises when participation in the research reveals evidence of a psychological or emotional problem in a participant.

Screening for risk factors. Some individuals can be especially vulnerable to the risks posed by participation in a study. For example, people with histories of cardiovascular disease would be especially vulnerable to the physical risks posed by strenuous exercise and people with certain personality characteristics would be especially vulnerable to high levels of psychological stress. Researchers must establish screening procedures to ensure that people at special risk do not participate in the research. Some professional associations have established standardized screening procedures, such as the American College of Sports Medicine’s (2010) guidelines for exercise testing. When standardized guidelines are not available, researchers must consult with knowledgeable professionals to establish appropriate screening procedures and participation criteria.

Unanticipated harmful effects. Even the best planned research can have unanticipated adverse effects on participants. These effects and the possible responses to them are illustrated by two of the studies that aroused behavioral scientists’ concern with the ethics of research. In the early 1960s, Milgram (1974), thinking about the guards at Nazi concentration camps in the 1930s and 1940s, became interested in why people would obey supervisors’ orders to harm others. He designed a series of laboratory experiments to test some of the factors he thought might affect this behavior. He recruited participants for these experiments from the general population through newspaper advertisements and paid them $4.50 in advance for an hour’s participation (about $32 today, after correcting for inflation). When participants came to the lab, an experimenter greeted them and introduced them to another “participant,” actually a confederate playing the part of a participant. The experimenter explained that the study investigated the effect of punishment on learning: A teacher (always the participant) would attempt to teach a learner (always the confederate) a list of words by giving the learner a painful electric shock every time the learner made a mistake. With each mistake, the teacher would have to increase the shock level, starting at 15 volts and going up to 450 volts in 15-volt increments. The 450-volt level was described as being extremely dangerous. During the “teaching” process, the confederate was in a separate room from the participant; he made a preset series of errors but received no shocks. He had an indicator so that he could give predetermined responses to different levels of shock, ranging from slight moans at low levels to apparent physical collapse at higher levels. Milgram’s research question was whether participants would continue to give shocks after it became apparent that the learner was in extreme pain. Almost two thirds did but exhibited severe stress symptoms while doing so. This degree of stress had not been anticipated by Milgram or by a group of clinical psychologists and psychiatrists who had reviewed a detailed description of the study before it began.

About a decade later, Zimbardo (1973) became interested in how social roles affect behavior. He and his colleagues designed a simulation in which paid college students were randomly assigned to play the roles of guards and prisoners in a simulated prison. Concerned about the possible effects of stress on the participants, who would be living their roles 24 hours a day in a realistic prison environment, the researchers used standardized psychiatric screening instruments to identify potential participants who might be especially vulnerable to stress. These individuals were not recruited for the study. Despite this precaution, one “prisoner” developed severe stress symptoms a few days into the simulation and was removed from the study for treatment. A few days later, a second “prisoner” developed similar symptoms.

What should researchers do if faced with unanticipated severe negative effects of their research, as were Milgram and Zimbardo? Zimbardo’s and Milgram’s responses illustrate the alternatives available. Zimbardo and his colleagues called off their study. After considering the issues, they decided that the knowledge they expected to gain from the research was not worth the harm accruing to participants. Milgram made the same kind of risk- benefit analysis but came to the opposite conclusion: The importance of knowing why people would continue to follow orders to hurt others despite the stress they experienced outweighed the harm caused by the stress. When faced with unexpected harm to participants, researchers must suspend the study, inform their IRB of the problem (an option not available in Milgram’s time), and conduct a new risk-benefit analysis based on what occurred in the study. If the researchers believe that the expected benefits of the research justify the harm to participants and want to continue the research, the IRB must conduct a new review of the research based on the new risk-benefit considerations. The research must be held in abeyance until the IRB gives approval to continue; the research may not continue without that approval.

Sometimes even minimal-risk studies result in idiosyncratic adverse reactions in participants. Koocher and Keith-Spiegel (2010), for example, relate the case of a young woman who broke down in tears while listening to a piece of popular music as part of an experiment. It turned out that the song had sentimental associations with a former boyfriend who had recently dropped the participant for another woman. When such reactions occur, the researcher should stop the experimental session and provide appropriate assistance to the participant. A more difficult issue is determining whether a participant’s response indicates a general risk that could affect all participants in the research or whether the response is unique to that person. No general rules can be established, but three indicators are the severity of the response, the participant’s explanation for the response, and the researcher’s experience with the research procedure that elicited the response. A severe response is more problematic than a mild response; a cause unique to the individual (as in the case just described) is less problematic than a general or unknown cause; and if the first adverse response occurs only after many participants have undergone the procedure, there is less problem than if it occurs early in data collection. In any case, when faced with an unanticipated adverse response, it is wise to suspend the study and discuss the situation with more experienced colleagues before making a decision on how to proceed.

Discovering psychological problems. Some psychological research focuses on factors related to psychological disorders, such as depression. Frequently this research is conducted by having samples of participants from nonclinical populations complete self- report psychological screening instruments and other measures. The researcher then correlates the scores on the screening instrument with the scores on the other measures or selects people for participation in research on the basis of their scores on the screening instrument. What should you do if a participant’s score on a screening instrument or behavior in a research setting suggests the presence of a severe disorder? Should you intervene by attempting to persuade the participant to seek treatment?

Stanton and New (1988) note that both costs and benefits are involved in referring participants for treatment:

Possible benefits … include amelioration of … distress and promotion of a positive perception of psychological researchers as caring professional… .A possible cost is the potentially iatrogenic labeling of subjects. A label of “depression” given by an authority may translate as “abnormal” in the view of the subject. (p. 283)

In a survey of depression researchers, Stanton and New (1988) found a wide range of opinions on how to resolve this dilemma, ranging from “‘it is very much a responsibility of researchers to give attention to the special needs of depressed subjects’” to “‘any follow-up of depressed subjects represents an unwarranted invasion of privacy’” (p. 283). However, Stanton and New also found a general consensus that something should be done and suggested some guidelines. They suggest that, as a minimum, all participants in studies of psychological or emotional problems be given information about available treatment resources, such as student counseling centers. Researchers could also offer to discuss participants’ responses with them; this discussion could be a vehicle for referral. Whether researchers should take the initiative and contact participants is more problematic (Stanton & New, 1988). If researchers are contemplating this option, they should include the possibility of follow-up contact in their consent forms in order to avoid invasion of privacy. The follow-up should be conducted by someone with sufficient training and experience to determine if referral to treatment is warranted; screening instrument scores alone are not a sufficient basis for referral. Stanton and New found that over 40% of depression researchers who worked with nonclinical populations made no provisions for dealing with the potential problems of distressed participants; such provisions must be made.

The principles of voluntary participation and informed consent give research participants the right to withdraw consent from research after it has begun. This right is absolute; researchers are not permitted to use any form of coercion or inducement to persuade withdrawing participants to continue. Specifically, participants may not be threatened with the loss of any benefits promised to them for participation. If participants are paid, whenever possible the payment should be made before data are collected to avoid the perception that the payment might be withheld if the participant withdraws from the research.

Even though participants are informed of their right to withdraw from the research, they may be reluctant to exercise that right. Milgram (1974) noted that many participants in his obedience studies seemed to feel they had entered into an implicit contract with the researcher: Having agreed to participate, they felt morally bound to continue to the end despite the distress they experienced. Milgram also suggested that this perceived contract might be seen as especially binding when people are paid for their participation. Research with children has found that most children age 8 and older understand their right to stop participating in a study and that this understanding increases with age (Miller, Drotar, & Kodish, 2004). However, children may have difficulty in saying no to an adult. Rather than asking that an experimental session be terminated, children may show behavioral indicators of unwillingness to continue, such as passivity or fidgetiness, or verbal indicators, such as frequently asking, “When will we be done?” (Keith-Spiegel, 1983). Researchers must be sensitive to these problems and ask participants if they wish to continue if they exhibit indicators of unwillingness, reminding them of their right to withdraw.

Ethical Considerations Following Data Collection

After researchers have collected data from a participant, a number of ethical obligations remain. These obligations include alleviating any adverse effects produced by the research procedures, educating participants about the study, explaining any deception that was used, compensating members of control groups who were deprived of a benefit during the research, and maintaining the confidentiality of participants’ data.

Sometimes the procedures used in research induce predictable adverse effects in the participants. For example, research on the effects of alcohol consumption induces at least mild intoxication and research on the effects of stress subjects participants to stress. Before participants leave the laboratory, researchers must ensure that any such effects are removed and take any other precautions that might be necessary to protect the participants’ welfare. For example, a complete and sensitive debriefing should be conducted so that the participants understand the necessity of the procedure that caused the unpleasant effects, even when fully informed consent was obtained beforehand. Zimbardo (1973) and his colleagues held group discussions with their participants to let them air their feelings and help them resolve their anxieties about their experiences in the simulated prison. If the procedures leave the participants temporarily physically impaired, as with alcohol consumption, they should stay in the laboratory until the effects wear off. If they live some distance from the research site, it is wise to provide transportation to and from the site, such as by providing taxi fare. In some cases, long-term follow-ups might be advisable to ensure that all the negative effects of participation have been removed. Both Milgram (1974) and Zimbardo (1973) conducted such follow-ups. However, if follow-ups are contemplated, they must be included in the informed consent form.

After a person completes participation in research, the researcher conducts a post-experimental interview or debriefing. This interview has three functions (Sharpe & Faye, 2009): educating the participants about the research, explaining any deception that was used, and eliciting the participants’ aid in improving the research. The first two functions are ethical obligations and are part of a process called debriefing, which is discussed here; Chapter 16 discusses the third function. This section examines three issues concerning debriefing: the components of a debriefing, constructing an effective debriefing, and potential harm that might come from debriefing.

Components of debriefing. A debriefing can have as many as five components (Greenberg & Folger, 1988; J. Mills, 1976; Sieber, 1992). The first component, which is part of all debrief- ings, is educational. Researchers have an ethical obligation to educate participants about the research (APA, 2002a). Such education often comprises the primary benefit derived by participants recruited from subject pools and so is especially important in those cases. If possible, provide this information at the end of the participant’s research session, but no later than the conclusion of the research (APA, 2002a). Explain the purpose of the research, including the dependent and independent variables, hypotheses, the procedures used,and the rationale underlying the hypotheses and procedures. Also explain the short- and long-term scientific and social benefits expected from the research. Participants should have an opportunity to have their questions answered and should be given the name and telephone number of a person to contact if they have questions later. In short, participants should leave the research understanding that they have made a contribution to science.