Formulating Research Hypotheses

Refining a topic into a question

Characteristics of a good research question

Purposes of the literature review

Primary versus secondary sources

Implications of Replication Research

Considerations in Conducting Replication Research

Designing Research for Utilization

Independent and dependent variables

Dissemination of Research Results

Bias in the Formulation of Research Questions

Suggestions for Further Reading

Questions for Review and Discussion

Scientists conduct research to answer questions. As we noted in Chapter 1, these questions can be posed by theory, by practical problems, by the need to evaluate an intervention, or by the investigator’s curiosity. This chapter examines four issues related to research questions: formulating research hypotheses, the role of replication research in behavioral science, designing research for utilization, and bias in hypothesis formulation.

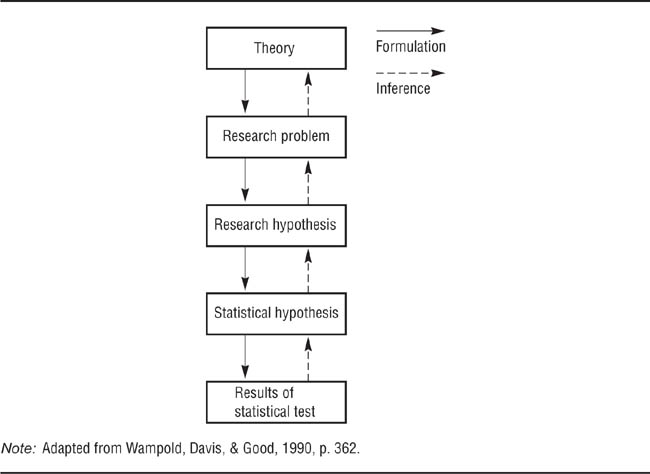

The first problem any researcher faces is that of coming up with a research question and refining that question into a testable hypothesis. Solving that problem involves a process made up of the elements shown in Figure 5.1. Although we present these elements as separate steps in a sequential process, in practice a researcher may work on two or more elements simultaneously.

Background for research consists of everything a researcher knows about a potential research topic. This knowledge can take two forms. Informal background consists of your personal experience, what you learn from your family life, work, recreation, and so forth. Life experiences generate interest in aspects of human behavior that can evolve into research topics and can provide the bases for specific hypotheses. Formal background consists of the sum of your education and training in behavioral science. Knowledge of theory, research results, and the methods available for conducting research provide the scientific basis for carrying out research.

Note the reciprocal relationship between background and the next element shown in Figure 5.1, choosing a topic. As you think about doing research on a topic, you may realize you don’t know enough about theory, prior research on the topic, or research methods to continue the process of hypothesis formulation, and so have to go back and develop more formal background before continuing. Developing a formal background involves the process of literature reviewing, which is described later in this chapter. The need to improve your formal background can sometimes feel frustrating because it appears to interrupt the flow of the research project—just as you’re getting started, you have to stop and back up. This backing up can be especially frustrating when working under a deadline, such as when developing a thesis or dissertation project. However, an inadequate background inevitably leads to other problems farther down the line, such as poor research design or data analysis, or the inability to rule out alternative explanations for your results. The time you invest improving your formal background near the start of a project definitely pays dividends at its end.

The Process of Formulating a Hypothesis.

Two factors influence the choice of a research topic: the researcher’s interest in the topic and the feasibility of carrying out research on the topic.

Interest. Choice of a topic for research grows naturally from the researcher’s background: Different people conduct research on different topics because their personal and professional backgrounds give rise to different interests. Interest in a topic is important because interest leads to commitment to the research; this commitment carries the researcher through times of problem and frustration during the project. A strong interest in a topic also usually produces a strong formal background—the interest leads you to read up on what is already known about the topic. Choosing a topic of personal interest to you therefore usually leads to better-quality research than does a less personally interesting topic.

However, sometimes you may feel pushed toward a research topic that you don’t find particularly interesting. For example, a student might be assigned to be a professor’s research assistant and feel compelled to do his or her own research on the professor’s topic. This feeling of being pushed in an uninteresting direction might arise because the student believes that such behavior is expected or because it seems to be convenient to be able to make use of the professor’s laboratory and equipment. In other cases, researchers might feel that their personal interests are not valued by other psychologists and so they start researching a topic that is less interesting to them but more prestigious. However, because low interest often leads to low commitment, the costs of doing research you find uninteresting, such as low motivation and easy distraction, should be carefully weighed against any expected benefits.

Students should also investigate the accuracy of their belief that they should investigate research questions that match their research interests to those of the professor with whom they work. A good approach is to discuss this issue with the professor; in doing so, a student might find that the professor supports his plan to pursue his own research. Moreover, if the professor does not feel sufficiently knowledgeable about the student’s area of interest, she can still provide advice or can refer the student to someone better able to help him. There are two points to bear in mind about this question of whose interests to follow, yours or your professor’s. First, sometimes students are expected to follow directly in their professor’s footsteps, but sometimes they are not; it depends on the intellectual traditions of the university, department, and professor. Investigate these traditions by talking to professors and advanced students in the department. Second, if you are a research assistant, you may be expected to work on the professor’s research while pursuing your own interests in your “spare time,” even with the professor’s support. You must clarify these role expectations.

Feasibility. In addition to choosing an interesting research topic, you must be sure it is feasible to conduct research on the topic. All research requires resources, but if the resources required to conduct research on a particular topic are not readily available, it might not be practical to pursue your idea. Some topics, such as psychopathology or learning disabilities, require access to special populations; are these research populations available? Other topics, such as the physiological bases of behavior, require special equipment; if the equipment is not on hand, the research cannot be conducted. It may also be difficult to gain access to certain settings, such as schools or factories, and the time required for longitudinal or prospective research may not be available. When choosing a research topic, then, it is extremely important to ask yourself both “Do I want to do research on this topic?” and “Can I do research on this topic?”

One of the more difficult tasks that novice researchers face is coming up with a research question once they have chosen a topic. This section discusses three aspects of question formulation: refining a broad topic into a specific, researchable question, the characteristics of a good research question, and sources of ideas for research questions.

Refining a topic into a question. Once a general area of interest is selected, the researcher must narrow the topic down to a more specific research question on which data can be collected. Beins and Beins (2012) refer to this stage as preliminary research, or the research you do before you have a focal question. At this stage, you should consider the questions that seem most viable as research topics and should skim through sources to help you evaluate a topic’s potential, and begin to narrow your focus. Let’s say you are interested in the topic of jealousy, which is, of course, an aspect of the broader topic of interpersonal relations. As shown in Figure 5.2, your pre-research will likely point to questions such as “What aspect of jealousy interests me: jealousy over possessions, jealousy over social position, romantic jealousy, or some other aspect?” If you choose romantic jealousy, when you continue your pre-research you will find that that others have distinguished between jealousy in marriage and jealousy in premarital relationships. If you decide your interest is in premarital jealousy, you can then consider its possible causes or effects. Candidates include causes due to developmental, situational, or personality factors. If you’re interested in personality variables as a cause of jealousy, what aspect of personality interests you—for example, paranoia, need for affiliation, or self-esteem? When you’ve answered these questions, you’ve refined your topic into a researchable question; that is, you can now phrase the question in terms of the relationship between two operationally definable variables, such as “Is self-esteem related to jealousy in premarital relationships?”

Refining the Topic of Jealousy into a Research Question.

You subdivide broad concepts until you reach a specific concept you can address in a study.

Characteristics of a good research question. While going through this refining process, keep one question always in mind: Is this going to be a good research question? In the broadest sense, a good research question is one that has the potential to expand our knowledge base. Three characteristics of a research question affect its potential for increasing knowledge. The first characteristic is how well grounded the question is in the current knowledge base. The problem must have a basis in theory, prior research, and/or practice; unless the question is anchored in what is already known, we cannot judge how much it can add to the knowledge base. At this point the researcher’s background comes into play—identifying the ways in which the research question will expand our knowledge of human behavior.

The second characteristic of a good research question is how researchable it is—that is, how easy it is to formulate clear operational definitions of the variables involved and to develop clear hypotheses about the relationships between the variables. Consider the hypothetical construct of codependency. As Lyon and Greenberg (1991) point out, because there is no theory underlying the construct, there are no criteria for determining whether any particular person is codependent; that is, there is no way to develop a clear operational definition for codependency. This problem is aggravated because the symptoms usually used to describe codependency overlap considerably with those of other psychiatric diagnoses, making it almost impossible to say whether a person who presents these symptoms exhibits “codependency” or one of the more traditional personality disorders. This problem of overlapping categories represents poor discriminant validity in measuring the construct, an issue we will discuss in the next chapter. If codependency cannot be operationally defined, it cannot be the subject of research.

The third characteristic of a good research question is its importance. The more information that the answer to a research question can provide, the more important it is. Research can add information to the scientific knowledge base in many ways. For example, practitioners’ experiences may lead them to suspect that two variables, such as psychological stress and physical health, are related. Research can provide empirical evidence that supports or refutes the existence of the relationship. If no relationship is found, practitioners’ and researchers’ efforts can go in other directions. Once the existence of a phenomenon is established, determining why a phenomenon occurs is more informative than additional demonstrations that it does occur. Consider the common finding that mothers are absent from work more often than are fathers (Englander-Golden & Barton, 1983). This descriptive finding provides information that is nice to know, but research that tells us why the difference occurs allows us to understand, predict, and perhaps design interventions to alleviate the problem.

A research question that simultaneously tests several competing theories provides more information than research that tests a single theory. If different theories predict different outcomes under the same set of conditions, then a research question phrased as a comparison of the theories—which theory correctly predicts the outcome—can tell us which is more valid. For example, psychoanalytic theory postulates that the venting of aggressive impulses (catharsis) provides for a release of anger and so reduces the likelihood of future aggression; learning theory, in contrast, postulates that the pleasant feeling brought about by expressing aggression will reinforce aggressive impulses and increase the likelihood of future aggression. A study comparing the two theories found that venting verbal aggression increased future verbal aggression, thereby supporting the learning theory view of aggression and simultaneously disconfirming the psychoanalytic view, at least for that form of aggression (Ebbesen, Duncan, & Konecni, 1975).

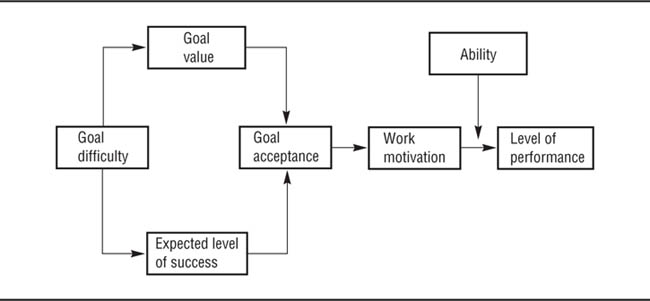

If you test only one theory, test a hypothesis derived from a proposition that is important to the theory. Some propositions are crucial to a theory—if the proposition is wrong, the entire theory is wrong. Other propositions are more peripheral to a theory—if they are correct, that’s good, but if they are wrong, the theory will still survive. For example, a central proposition of Locke and Latham’s (1990) goal-setting theory of work performance is that more difficult goals are valued more highly than less difficult goals; if hypotheses based on this proposition are not supported, then the theory is not valid. Other possible hypotheses related to goal setting, such as the hypothesis that goals set by a supervisor lead to lower goal commitment than goals selected by the workers themselves, are less central to the theory. Therefore, the ambiguous results of research on this hypothesis do not affect the theory, even though the hypothesis does address an important practical question (Locke & Latham, 1990).

Theory maps are an excellent tool for outlining a theory and understanding how a hypothesis follows from that theory (Motes, Bahr, Atha-Weldon, & Dansereau, 2003). A theory map includes information such as the history of the theory, information about why the theory is important, evidence supporting or refuting the theory, and (if applicable) similar and competing theories. A theory map also includes links to major references that address the theory. Similar maps can be created to summarize the results of an individual research study; research maps include information about the purpose of the research, the methodology used, the obtained results, the implications of the findings, and possible alternative explanations for the study outcome (see Motes et al., 2003, for an example). Figure 5.3 contains a theory map based on Baddeley’s (2000) model of working memory. This model proposes that working memory is governed by a central executive system that serves as a gatekeeper, deciding what information to process and how to do it, including what resources to allocate.

Theory Maps.

A theory map includes information such as the history of the theory, information about why the theory is important, evidence supporting or refuting the theory, and (if applicable) similar and competing theories. A theory map also includes links to major references that address the theory.

Sources of ideas. Where do ideas for good research questions come from? There are, of course, as many answers to this question as there are researchers. However, some suggestions for getting started, drawn from several sources (Evans, 1985; McGuire, 1997; Tesser, 1990; Wicker, 1985) are listed in Box 5.1 and outlined next. These categories are not intended to be mutually exclusive: Any one idea could fall into more than one category, such as when theory is applied to solve a practical problem.

Theory

Confirmation

Refutation

Comparison

Merger

Practical Problems

Problem definition

Solution seeking

Validating practitioners’ assumptions

Prior Research

Case studies

Conflicting findings

Overlooked variables

Setting and expanding boundaries

Testing alternative explanations

Logical Analysis

Analogy

Looking at things backward

Everyday experience

In Chapter 1, we noted that theory is central to research, and basic research is conducted to test hypotheses derived from theories, and many applied studies are strong grounded in theory. Researchers can have different motives for testing theories: They can be attempting to find evidence to support a theory they favor, to find evidence to refute a theory they don’t like, or to compare competing theories. Chapter 1 also showed how existing theories can be creatively merged to form new theories that need testing, as Abramson, Seligman, and Teasdale (1978) merged the theory of learned helplessness and attribution theory into a new theory of depression. It is interesting to note that Abramson et al. took two theories that were based primarily on laboratory research and combined them in a way that addressed a practical problem. Seligman (1975) originally discovered the learned helplessness phenomenon in research with dogs, and most research on attribution theory has been conducted in the laboratory (Weiner, 1986).

Practical problems themselves also provide research ideas. One aspect of problem-oriented research is problem definition: determining the precise nature of a suspected problem. For example, if one suspects that playing violent video games causes children to be aggressive, then applied research can answer questions such as: Is there, in fact, a relationship between playing violent games and aggression? If so, to what forms of aggression is it related? Is the relationship the same for girls and boys, and for children of different ages? Is the relationship causal? If so, what about violent video games causes aggression; for example, is it the violence itself or the exciting nature of the game as a whole? Once a problem has been defined, potential solutions can be developed and tested through applied research. Problem-oriented research can also test the validity of psychological assumptions made by practitioners in behavioral science and other fields. The legal system, for example, makes a number of assumptions about eyewitness perception and memory and about the validity of aspects of witnesses’ behavior, such as their apparent degree of confidence while testifying, as indicators of the accuracy of their testimony. Research has shown many of these assumptions to be incorrect (Wells et al., 2000).

Prior research can also be a valuable source of ideas for empirical investigation. Case studies can provide hypotheses for investigation using the correlational and experimental strategies, and the hypotheses about the causality of relationships found in correlational research can be tested experimentally. The results of different research studies on a hypothesis can be inconsistent, with some supporting the hypothesis and others not, and research that shows why the inconsistencies exist can be very informative. For example, a study one of us conducted as a graduate student (Whitley, 1982) showed that two earlier studies obtained conflicting results because of differences in their operational definitions of the independent variable. Sometimes while reading through the research on a topic, you come to realize that an important variable has been overlooked and needs to be included in research on the topic. For example, Shelton (2000) has pointed out that researchers most often study racial prejudice from the perspective of Whites and that Blacks’ perspectives are sought primarily in studies of their experience as targets of prejudice. Models of Blacks’ racial attitudes or of how minority groups process information about their own or other ethnic groups have not been developed.

Research is also necessary to establish the boundary conditions of effects found in earlier research—the conditions under which the effect operates. For example, do effects found in the laboratory hold up in natural settings? As noted in Chapter 1, advances in neuropsychology have provided evidence for the previously controversial idea that new nerve cells develop throughout the lifespan (Kempermann & Gage, 1999). Research can also be conducted to extend the results of prior research to new technologies. For example, research on the effects of violent video games on aggression was an extension of research on the effects of televised violence on aggression (Anderson et al., 2010). Finally, perusal of the research literature can also suggest possible alternative explanations for research results that can be tested in new research. For example, Thompson, Schellenberg, and Husain (2001) demonstrated that the “Mozart effect,” or the finding that people’s performance on spatial tasks improves after listening to music composed by Mozart, can be explained by other processes. They found that listening to Mozart’s music improves mood and increases arousal, and that it is these changes that account for the improved performance. That is, there is nothing special about Mozart’s music, per se; research has shown that many factors which improve people’s mood also improve their cognitive functioning (Thompson et al., 2001).

Logical analysis can lead to ideas for research in several ways. Reasoning by analogy looks for potential similarities between psychological processes and physical or biological processes. McGuire (1964), for example, was interested in the problem of how to prevent people from being influenced by attempts at persuasion and hit on the analogy of inoculation: If injecting a person with a weakened version of an infectious agent can prevent infection by the agent, can presentation of weakened versions of persuasive arguments prevent persuasion when the full-strength arguments are presented? (It can.) One can also take accepted principles and look at them in reverse. For example, primary care physicians list behavioral factors as the primary cause of obesity and stigmatize their overweight patients who do not modify these behaviors (Foster et al., 2003). However, research suggests that weight stigmatization itself increases the likelihood of engaging in unhealthy behaviors, such as binging or failing to exercise (Puhl & Heuer, 2009). Lastly, one can look at the “mirror image” of prior research. For example, if people self-disclose personal information to someone they like, do they also like a people who self-disclose to them? Research suggests they do, even if that person is a new acquaintance (Vittengl & Holt, 2000).

Finally, don’t overlook your everyday experience as a source of research ideas. Every time you ask yourself, “Why do people act that way?” you have a potential research question: Why do people act that way? Singer and Glass (1975), for example, got started on their research on the relationship between perceptions of personal control and stress because they were struck by what seemed to them to be a curious phenomenon: People who experienced the same urban environment (New York City) reacted in very different ways—some developed stress symptoms and hated the city, whereas others found the city exciting and loved it.

Once you have formulated your research question on the basis of your general background on the topic, it is time to conduct focused research; that is, you now should begin to read and evaluate sources that relate to your focal question. When doing so, you should read sources carefully and keep detailed notes, including keeping track of citation information for those sources (Beins & Beins, 2012). This process is called the literature review. The term literature review requires a little clarification because researchers use it in three ways. First, it is used to refer to the focus of this discussion, the process of collecting theoretical, empirical, and methodological information on a topic. The term is also used to refer to two products of that process: a comprehensive summary and analysis of theory and research on a topic (see Chapter 19) and to the part of the introduction section of a research report that presents the background of the study (see Chapter 20).

Purposes of the literature review. When used to develop the background for a study, the literature review has three purposes. The first is to provide a scientific context for the research and to validate it against the three criteria for a good research question. You want your research to be well grounded in the body of existing scientific knowledge so that it both ties in with and extends what is already there. The literature review helps you generate this context by bringing to light the theory and research relevant to your question. The literature review also lets you determine the important theoretical, practical, and methodological issues that surround your research question. When you report on your research, you will begin by showing the reader why your research was important to the scientific understanding of your topic; this aspect of the literature review gives you that information. Although your formal background in the topic will be helpful, the information in that background might not be specific or current enough to provide an appropriate context for your research question.

The second purpose of the literature review is to avoid duplication of effort. If you find your research question has been addressed a number of times using a variety of methods and has a reasonably firm answer, further research may not be productive. Although replication is important in establishing the reliability and validity of research results, eventually we have enough information to draw firm conclusions, at which point further research may be a waste of effort. However, new perspectives on old questions, such as applications to new settings or populations, can provide new information and so should be pursued. The issue of replication is discussed in detail later in this chapter. Reading major review articles on your topic of interest, if available, can help you answer the question of whether new research is warranted.

The third purpose of the literature review is to identify potential problems in conducting the research. Research reports contain information on the effectiveness of operational definitions, potential alternative explanations that must be controlled, and appropriate ways to analyze the data. Knowing in advance the problems that can arise in your research will help you avoid them. Creating theory and research maps (see Figure 5.3) can assist you with all three goals of a literature review.

Types of information. The purposes of the literature review imply that you should be looking for four types of information. First, you should be looking for relevant theories. Although your background in the topic will make you aware of some of the theories related to your question, make sure you know about all the relevant theories. This knowledge can help you in two ways. First, it may let you reformulate your research question into a comparison of theories, thereby providing more information than if you simply set out to test a single theory. Second, if your results are not consistent with the particular theory you favor, they may be consistent with another theory, which will provide your results with a niche in the knowledge base.

The second type of information to look for is how previous researchers have addressed your question. This information lets you know three things. First, you will know what has been done, allowing you to avoid unproductive duplication. Second, you will know what has not been done; to the extent that your research question—or your approach to answering that question—is novel, your research increases in importance. Third, you will know what still needs to be done to answer the question fully. The results of research studies often leave parts of their questions unanswered or raise new questions; to the extent that your research addresses such questions, it increases in importance.

The third type of information to look for concerns method: how prior research was carried out. This information includes settings, characteristics of participants, operational definitions, and procedures. This knowledge lets you anticipate and avoid problems reported by your predecessors. It can also save you work: If you find operational definitions and procedures that have worked well in the past, you might want to adopt them. There is nothing wrong with borrowing methods used by other researchers; in fact, it is considered a compliment, as long as you give credit to the people who developed them. In addition, using the same or similar methods in studying a phenomenon makes it easier to compare the results of the studies and to draw conclusions from a set of studies.

The fourth type of information to look for concerns data analysis. Research design and data analysis go hand in hand. It is both frustrating and embarrassing to collect data on a question and then realize you have no idea about how to analyze the data to find the answer to your question. Whether your analysis is statistical or qualitative, you must plan it in advance so that your analytic technique matches the type of data you collect (the next chapter touches on this issue again). Clearly, seeing how other researchers have analyzed their data can help you decide how to analyze yours. If you don’t understand the statistical techniques used in a study, consult a textbook or someone who has experience using the techniques. Huck, Cormier, and Bounds (1974) have written a very useful book about how to interpret the statistics used in research reports.

Primary versus secondary sources. Information about research can be found in either primary sources or secondary sources. A primary source is an original research report or presentation of a theory written by the people who conducted the research or developed the theory. A primary source will include detailed information about the research or theory laid out in complete detail. Research reports published in professional journals are examples of primary research sources. They provide complete explanations of why the research was conducted, detailed descriptions of how the data were collected and analyzed, and the researchers’ interpretations of the meaning of the results. Original presentations of theories can be reported in books, as Locke and Latham (1990) did with their goal-setting theory of work performance, or in professional journals, as Abramson, Metalsky, and Alloy (1989) did with their attributional theory of depression.

A secondary source summarizes information from primary sources. Examples of secondary sources include the introduction and discussion sections of research reports, journal articles and book chapters that review what is known about a topic, and textbooks. Secondary sources can also include nonprofessional publications such as newspapers, websites, and television programs. Secondary sources are useful because they provide information from primary sources in concise form, compare and contrast the strengths and weaknesses of studies and theories, and point out gaps in the research literature and topics for future research. Because secondary sources are summaries, they necessarily omit information from the primary sources. As a result, secondary sources sometimes provide inaccurate descriptions of the research results and the meaning of those results. For example, Friend, Rafferty, and Bramel (1990) describe the ways in which the results of Asch’s conformity study have been incorrectly described in secondary sources and Sackett, Hardison, and Cullen (2004) discuss how research on stereotype threat, which addresses how awareness of one’s own group’s stereotypes can hinder performance, has been oversimplified in the popular press. Therefore, when you find an interesting study described in a secondary source, you should go back to the original research report to see what it actually says.

Where to find information. Sources of information for literature reviews can be classified as published or unpublished. Published sources consist of professional journals and books and receive wide distribution to academic libraries. Most research and much theoretical work in behavioral science is published in professional journals. An important characteristic of most articles published in professional journals is that they have undergone peer review. Peer review is a process in which an article is evaluated prior to publication by experts on its topic and, in the case of research reports, the methodology it uses. If the article does not meet the quality standards set by the journal editor and evaluated by the reviewers, the report will not be published. Chapter 20 describes the review process in more detail; for now, let’s view it as a quality check.

Books are used to publish research reports in many areas of behavioral science, such as sociology and anthropology, especially reports of long-term field studies. In other areas, such as psychology, professional books are used primarily for literature reviews, the presentation of theories, and methodological issues, usually on a single topic or set of related topics. Books can be classified as either monographs or edited books. Monographs are written by one author or a team of authors; in edited books, each chapter is written by an author or a team of authors, with an editor or a team of editors contributing opening and closing chapters that provide a context for the other chapters. Textbooks, of course, provide overviews of topics at various levels of detail and sophistication. Introductory-level texts provide only broad and often highly selective pictures of a field, designed for students with little background on the topic. Specialized graduate-level texts, in contrast, go deeply into a topic, analyzing the theories and research methods used. Professional books and textbooks are usually, although not always, peer reviewed, but the review criteria are often less stringent than those for journal articles.

Unlike published research, unpublished research reports receive only limited distribution. This grey literature includes conference presentations, technical reports, white papers, standards, policies, and newsletters from professional associations. The PsycEXTRA database, maintained by the American Psychological Association (apa.org), has over 100,000 such records. Reports of research given at conventions and other professional meetings are also available through the Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC; www.eric.ed.gov). Programs from major conferences are often archived on the association’s website; conference papers not archived at PsycEXTRA or ERIC may be available from the authors. Research presented at a conference also may later be published, so you should search a database such as PsycINFO by author and topic to check this possibility. Rothstein and Hopewell (2009) provide detailed information about searching this literature.

Technical reports are summaries of research done under contract to a business or government agency; these may be available on the agency’s website. For example, an annual report on crime in the United States can be found on the Federal Bureau of Investigation website (www.fbi.gov/research.htm). The Catalog of U.S. Government Publications, which lists and indexes publications from U.S. government agencies, including research reports, is available at catalog.gpo.gov. Reports completed for private industry and foundations are increasingly available on the Internet; for example, the Education Testing Service website (www.ets.org) has a report on identifying reading disabilities in English language learners (Shore & Sabatini, 2009). Some technical reports are also available from PsycEXTRA and this site archives older reports that may have been removed from an agency’s website. Master’s theses and doctoral dissertations are normally held only at the library of the university where the work is done, but copies may be available on the university’s website or through Interlibrary Loan. Dissertation Abstracts International indexes doctoral dissertations. Digital or microfiche copies of dissertations can be purchased from ProQuest/UMI, the company that publishes the index.

Authors of research reports are a resource for obtaining information that was not included in the original report, such as a copy of a measure or a set of stimuli. The author may also be able to provide information on the topic of the article that has not yet been published and with advice on other sources of information that are available. The first page of most journal articles includes a footnote giving the postal and electronic mail addresses of one of the authors (usually the first author) and contact information for researchers is typically available on their institution’s website. Be aware, however, that the ready availability of author contact information has resulted in researchers being inundated with requests for research assistance. Before you write an author, be sure to check their website and/or their published articles to determine whether the information you need is already available. Do not expect an established researcher to do your work for you; for example, we have had requests for copies of our research articles simply because the student could not find a copy in her library—that is what interlibrary loan is for. We have also had students ask us to explain commonly used statistical analyses or to offer recommendations about the literature they should read. Be respectful of a researcher’s time and ask only those questions you truly cannot find the answer to using local resources or professors at your own institution.

Library research tools. It used to be that the physical holdings of one’s university library were crucially important. Today, of course, an astonishing amount of information can be accessed from electronic devices and the line between resources available from specific libraries or from the broader World Wide Web is difficult to draw; indeed, you may give little thought to where information is housed. Search engines allow you to readily access information; typing in an author’s name and article title, for example, will often lead you directly to a published manuscript. Most journals now also appear in both print and electronic form, although your access to these journals will depend on the services to which your university or local library subscribes. If you personally subscribe to a journal, you may also have electronic access through the publisher; this access may be extended to other journals offered by that publisher. There are also peer-reviewed journals which publish only electronic manuscripts (see www.psycline.org/journals/psycline.html, for a list of electronic journals in psychology and the social sciences by title, topic, and key words). Books are also increasingly likely to appear in electronic form through sites such as Google Scholar.

This easy access makes literature searching seem seductively simple: sit down at the computer, type in what you are looking for, and sources come up. Unfortunately, there are clear limits to this approach and it may not be the most effective way to locate information. Be aware that “Googling” a topic will provide links to frequently accessed articles and websites, but this is not the same as identifying the most relevant or most important research in an area. Which items come up first depends on how a particular search engine ranks the content; the result is that irrelevant articles may appear first and relevant articles may not be captured by your search. Similarly, Wikipedia provides overviews of countless topics in the social sciences, but the quality of this information depends on the expertise of the people who created the entry; “Googling” and Wikipedia might be a good place to begin one’s preliminary search, but should not be relied on for the focused stage of research (and the primary research sources cited in sites such as Wikipedia should definitely be verified).

To be an effective researcher, you must take the time to learn the tools that will help you find the best scholarly information about your topic of interest. One such tool is the library’s online catalog, which indexes the library’s holdings in the form of books, periodicals, government documents, dissertations and theses written at the institution, audio and visual records, and other materials. The catalog can be searched by authors’ names, titles, subjects, and key words. Most universities offer online access to databases, such as Psyc- INFO, PsycARTICLES, Academic Search Premier (EBSCOhost), and Sociological Abstracts. You may be able to access these databases both on and off campus; some libraries also partner with other universities and you may be able to access the resources of those institutions.

The mechanics of searching a computerized index vary depending on the particular software a library uses. Constructing a good search strategy requires knowledge both of the topic you are researching and of the way the search software operates, including the list of terms that you tell the program to look for in the index. As Durlak and Lipsey (1991) described their experience using a psychological database: “We discovered … that only one of every three entries appearing in our computer-generated study lists was relevant [to our research] and approximately two thirds of the relevant studies were not picked up via the computer search” (p. 301). Kidd, Meyer, and Olesko (2000) review 20 databases that are relevant to psychology and offer tips on how to use them; Beins and Beins (2012) provide detailed information about how to effectively search these sources. Library instruction is also likely available at your institution.

Because research reports, theoretical articles, and literature review articles cite the studies on which they are based, a second source of studies is the bibliographies of these publications. If one or a few articles are central to the topic under review, you can conduct a citation search. Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) indexes all the sources cited in articles published in major journals in the social and behavioral sciences. Therefore, if Nguyen and Jones have written a particularly important article on a subject, you can look up all the subsequent journal articles that cited Nguyen and Jones’s work; these articles probably deal with the same topic and so are probably relevant to your literature review. Reed and Baxter (2003) explain how to use SSCI. PsycINFO also includes information about how often an article is cited, but only in other articles in its database.

What should you do if you conduct a literature search and cannot find information relevant to your topic? Your first step should be to think about the search you conducted. If you conducted a computer search, did you use the correct search terms? Each index has a thesaurus that lists the terms the index uses to categorize articles; if you don’t use these “official” terms, you might not find what you’re looking for. If you are confident that you’ve used a correct search strategy, you must then ask how researchable your topic is. If no one has ever conducted research on your question before, it might be because no one has been able to find a way to do so; alternatively, you might be breaking new ground and therefore be dealing with an especially important question. Also, keep in mind that journals are reluctant to publish research results that do not support the hypotheses tested (Greenwald, 1975); consequently, other people may have done research on a topic and have been unable to find support for their hypotheses, so their research has not been published. One way to check on this possibility is by using the grey literature, as discussed above, or accessing the so-called invisible college: informal networks of people who conduct research on a topic. These people may be able to provide information about research that hasn’t made it into print. Websites such as the Community of Science (www.cos.com) and the Social Psychology Network (www.socialpsychology.org) allow you to search for experts by your topic of interest.

Evaluating information. Once you’ve completed your search, much of the information you will review will be from research reports. Novice researchers often tend to accept the information in these reports, especially those published in professional journals, rather uncritically. Because these reports appear in peer-reviewed journals, the reasoning goes, they must be correct; who am I to question the judgments of experienced researchers, reviewers, and editors? However, as noted in the previous chapter, no study is perfect. Therefore, read research reports critically, keeping alert for factors, such as alternative explanations of results, that might lessen the validity of the conclusions. Take these validity judgments into consideration when formulating your hypotheses, giving the most weight to the information that you judge to be most valid. The factors that contribute to the validity of research are discussed throughout this book, and Box 5.2 lists some questions you should bear in mind while reading research reports.

To give you practice in applying such questions to research reports, Huck and Sandler (1979) have compiled summaries of problematic studies. Working through their book will help you develop the critical sense you need to evaluate research reports. An astonishing amount of information is now readily available on the Internet but evaluating the accuracy of this information requires due diligence. As Driscoll and Brizee (2012) note, the ready availability of such information makes it tempting to accept whatever you find. Rather than succumb to this temptation, develop the skills you need to evaluate the information on the Web. In Box 5.3, we offer strategies for effectively doing so.

When evaluating a research report, ask the following questions. These questions are phrased primarily in terms of experimental research, but the same principles apply to other research strategies.

1. |

Internal validity: Might differences between groups be accounted for by something other than the different conditions of the independent variable? |

a. |

Were research participants randomly assigned to groups so that there was no systematic bias in favor of one group over another? Could bias have been introduced after assignment of participants because of different dropout rates in the conditions? |

b. |

Were all the necessary control groups used, including special control groups in addition to the baseline group to account for possible alternative explanations? Were participants in all groups treated identically except for administration of the independent variable? |

c. |

Were measures taken to prevent the intrusion of experimenter bias? |

d. |

Were measures taken to control for possible confounds, such as history, statistical regression, order effects, and so forth? |

2. |

Construct validity: Did the researchers use appropriate operational definitions of their independent and dependent variables? |

a. |

Is there evidence for the validity of the operational definitions? |

b. |

How good is that evidence? |

3. |

Statistical validity: Were the data analyzed properly? |

a. |

Was the statistic used appropriate to the data? |

b. |

Were the proper comparisons made between groups? For example, were follow-up tests used in multigroup and factorial designs to determine which differences in means were significant? |

c. |

Were the results statistically significant? If not, was there adequate statistical power? |

4. |

Generalization: Did the research have adequate external and ecological validity? |

a. |

Research participants: From what population was the participant sample drawn? Is it appropriate to the generalizations the authors want to make? |

b. |

Experimental procedures: Did the operational definitions and research setting have adequate realism? |

c. |

Did the researchers use enough levels of the independent variable to determine if there was a meaningful relationship with the dependent variable? |

d. |

Are the necessary independent variables included to detect any moderator variables? |

5. |

Going from data to conclusions: |

6. |

Of what value is the research? (No attempt has been made to order the following list in terms of importance.) |

a. |

Is the size of the relationship found large enough to have practical significance in terms of the goals of the research? |

b. |

Does it provide an answer to a practical problem? |

c. |

Does it have theoretical significance? |

d. |

Does it suggest directions for future research? |

e. |

Does it demonstrate previously unnoticed behavioral phenomena? |

f. |

Does it explore the conditions under which a phenomenon occurs? |

g. |

Does it represent a methodological or technical advance? |

Source: Adapted from Leavitt (1991)

In closing this section on literature reviewing, we note that although Figure 5.1 shows literature reviewing and the next element in the hypothesis formulation process, formulating hypotheses, as separate elements, they are actually concurrent, interdependent processes. You will use the information from the literature review to help you refine your general research question into a specific hypothesis. Simultaneously, as your hypothesis becomes more specific you will find yourself in need of more specific information from the literature review, such as the advantages and disadvantages of different operational definitions and variables that you must control in order to rule out alternative explanations for your results. You may also need to continue your literature review after you have analyzed your data as you search for possible explanations of unexpected findings and look for the ways in which those findings fit in with what is already known about your topic.

Once you have formulated your research question and refined it based on the information derived from your literature review, you must formulate one or more specific hypotheses to test in your research. Each hypothesis you formulate will take two forms: a narrative research hypothesis and a statistical hypothesis.

Research hypotheses. The research hypothesis states an expectation about the relationship between two variables; this expectation derives from and answers the research question, and so is grounded in prior theory and research on the question. For example, for the research question “Is self-esteem related to premarital romantic jealousy?” the research hypothesis (based on a thorough literature review) could be stated as “Unmarried members of romantic relationships who have low self-esteem will exhibit more romantic jealousy than will unmarried members of romantic relationships who have high self-esteem.”

Notice that the hypothesis specifies that a negative relationship exists between self- esteem and jealousy—low self-esteem is associated with high jealousy—not just that some unspecified type of relationship exists. Because of this specificity, the results of a study can unambiguously support or refute the hypothesis: Any outcome other than one in which low self-esteem is related to high jealousy means the hypothesis is wrong. An ambiguous research hypothesis, in contrast, can render the results of the research ambiguous. Consider the hypothesis “There is a relationship between self-esteem and jealousy” and this empirical outcome: High self-esteem is related to high jealousy. In one sense, these results support the hypothesis: There is a relationship between the variables. Yet the results directly contradict the relationship suggested by the results of the literature review. What are we to conclude? In this example of a single simple hypothesis, we can, of course, conclude that the research hypothesis “that we really meant to test”—the unambiguous hypothesis—was not supported. However, in research that tests multiple complex hypotheses, the conclusions may not be so clear-cut (Wampold, Davis, & Good, 1990). It is therefore always best to state research hypotheses in terms of specific relationships.

Because there are no controls, such as peer review, over the quality of the information posted on most Web pages, there are additional factors to consider when evaluating research reports posted on the Internet. Some factors to consider include the following:

1. |

Evaluate the Accuracy of the Web document. |

a. |

Is the author of the page listed and, if so, what are his or her credentials or level of expertise regarding the topic of the page? As Beck (1997) notes, answering this question can be surprisingly difficult because, even if the author is listed, her or his qualifications often are not. Moreover, the name listed on the page may be a Web master rather than the page author (Kapoun, 1998). Make sure you can distinguish between the two and, more generally, take the time to determine whether the author is a well- known, respected researcher on the topic. |

b. |

Who is sponsoring the Web page? As Henninger (1999) notes, you should look for sponsors who are from reputable organizations that do not have a financial interest in the topic; examples include well-known colleges, universities, research institutes, or public service organizations. She further points out that college or university Web sites may contain both official pages and unofficial personal pages; unofficial pages should be evaluated with greater scrutiny to ensure they reflect the most up-to-date scholarship. |

2. |

How Objective is the Information Provided? |

a. |

There are several questions you can ask to determine whether the information provided on a Web site is objective. Look for information about the Web page’s sponsor and whether contact information for that sponsor is listed. Then, ask for whom the site was written and for what purpose (Kapoun, 1998). Was the Web page designed to sell a product or service or to advocate a particular position on a political or social issue? If so, does the sponsor have a vested interest in selling a product or service and is the provided information biased toward doing so? If the site is sponsored by an advocacy organization, are the described research results biased toward their position on the issue and/or are studies with a different perspective downplayed or omitted (Henninger, 1999)? |

b. |

Another factor to consider is whether the information provided on the page is based on scholarly research or the authors’ opinion. Use only those pages that include citations that you can verify in the scholarly literature on your topic. Look for sources that offer a good balance of primary and secondary sources. Avoid sources that make broad generalizations or that overstate or oversimplify the topic (Driscoll & Brizee, 2012). |

3. |

Is the information up-to-date? |

There are several clues you can use to evaluate whether a page is current, including the date it was posted, when the page was last revised or edited, and whether provided links are current (Kapoun, 1998). Be careful about relying on pages that appear to be out of date.

Statistical hypotheses. The statistical hypothesis transforms the research hypothesis into a statement about the expected result of a statistical test. The research hypothesis “People low in self-esteem exhibit more romantic jealousy than people high in self-esteem” can be stated as either of two equivalent statistical hypotheses: (1) “There will be a significant negative correlation between scores on a measure of self-esteem and scores on a measure of romantic jealousy” or (2) “People classified as low on self-esteem will have significantly higher mean scores on a measure of romantic jealousy than will people classified as high on self-esteem.” The results of the appropriate statistical test can be compared to the statistical hypothesis to determine its validity.

The statistical hypothesis must accurately represent the research hypothesis. If the statistical hypothesis is not congruent with the research hypothesis, then the results of the statistical test will not provide accurate information to use in drawing conclusions about the validity of the research hypothesis. Consider the following example from Huck and Sandler (1979): Two educational researchers were interested in whether giving students classroom instruction on material covered by a textbook in addition to having them read the textbook would improve their scores on a test of the textbook material. Students were divided into three groups: Group 1 read the textbook and received classroom instruction on the material covered by the book, Group 2 just read the book, and Group 3 received classroom instruction unrelated to the topic of the book. At the end of the experiment, all the students took a 30-point test on the material the book covered; the groups’ mean scores are shown in Table 5.1. The researchers statistically tested their hypothesis that additional instruction would improve learning by comparing the mean score of Group 1 to the combined means of the other two groups. Notice the following:

1. |

The research hypothesis was that students who both received classroom instruction and read the textbook (Group 1) would do better than students who only read the textbook (Group 2). |

2. |

The research hypothesis transforms into the statistical hypothesis that the mean score of Group 1 would be greater than the mean score of Group 2. Group 3 is irrelevant to the research hypothesis, which does not say anything about students who have had no instruction (although the other groups could be compared to Group 3 to see if instruction had any effect at all on students’ knowledge of the topic). |

3. |

The researchers tested a different statistical hypothesis: that the mean of Group 1 was greater than the average of the means of Groups 2 and 3. Consequently, the results of the statistical test told the researchers nothing about the validity of their research hypothesis. |

Mean Scores Illustrating a Test of the Wrong Statistical Hypothesis

The research hypothesis called for a comparison of Groups 1 and 2, but the tested hypothesis was Group 1 versus the combination of Groups 2 and 3.

Group | ||

1 |

2 |

3 |

Textbook and Instruction |

Textbook Only |

No Textbook and No Instruction |

25.06 |

21.66 |

13.41 |

Figure 5.4 illustrates the way in which the process of hypothesis formulation affects the conclusions drawn about the validity of theories (or other bases for research questions). The solid line shows that a theory leads to the formulation of a research question. The question is stated as a research hypothesis, which is transformed into a statistical hypothesis. The statistical hypothesis is compared to the results of the appropriate statistical test. The broken line indicates the chain of conclusions drawn from the research results. Conclusions about the status of the research hypothesis (confirmed or disconfirmed) are based on the match between the statistical hypothesis and the results of the statistical test. The conclusions drawn about the research hypothesis are correct if and only if the statistical hypothesis is congruent with the research hypothesis. Similarly, the correctness of the answer to the research question depends on the validity of the conclusions drawn about the research hypothesis, and the validity of the conclusions drawn about the theory depend on the correctness of the answer to the research question. In essence, then, the validity of all tests of theory (and of other types of research) depends on congruence between the research hypothesis and the statistical hypothesis. This congruence, in turn, is partly a function of the specificity of the research hypothesis: The more specific the research hypothesis, the easier it is to formulate a congruent statistical hypothesis. The specificity of the research hypothesis depends strongly on the clarity and specificity of the theory being tested.

Hypothesis Formulation and Inference in Research.

In problem formulation, research hypotheses are derived from research problems, which are themselves derived from theory; the statistical hypothesis phrases the research hypothesis in terms of what the results of the statistical test would look like if the hypotheses were correct. The results of the statistical test are compared to the statistical hypothesis. In inference, use the statistical hypothesis to determine the implications of the results of the statistical test for the research hypothesis, and then determine the implications of the outcome of the research—whether or not the hypothesis was supported—for answering the research problem and for the theory.

Once you have formulated your hypotheses, you can design your study. In designing a study you must answer five questions:

1. |

“How will I conduct the study?” The answer to this question includes choosing a research strategy and a specific design within the chosen strategy. A research design is the specific way in which a strategy is carried out; for example, as shown in Chapter 9, there are a number of ways of carrying out the experimental strategy. |

2. |

“What will I study?” This question is answered by your choice of operational definitions for the hypothetical constructs you are studying. |

3. |

“Where will I conduct the study?” Will you use a laboratory or field setting? What specific laboratory set-up or field location will you use? |

4. |

“Whom will I study?” What population will you sample for your research participants and what sampling technique will you use? If you collect data from members of minority groups, you must design your research to take the groups’ cultures into account. See the Guidelines on Multicultural Education, Training, Research, Practice, and Organizational Change for Psychologists, adopted by the American Psychological Association (2002b) and Knight, Roosa, and Umaña-Taylor (2009) for factors to consider when conducting research with members of specific groups. |

5. |

“When will I conduct the study?” Will time factors such as hour of the day or season of the year affect the phenomenon you will study? Do you want to take a cross sectional or longitudinal approach to your study? |

Answers to these questions are discussed in Chapters 9 through 15; however, the process of answering these questions is related to the process of hypothesis formulation in two ways. First, if you have difficulty in answering any of these questions, you will want to expand your literature review or seek advice from others to find the answers. Second, you must check the feasibility of your answer to each question; that is, ask yourself, “Are the resources needed to carry out the study in this way available to me?” If the answer is no, you might have to reformulate your hypothesis, reformulate your research question, or even select a new topic.

After you have decided on a research design, you should write a research proposal; you will be required to do so for a thesis or dissertation or to apply for a grant. The proposal should lay out the theoretical and empirical bases for your research question and hypotheses (that is, their scientific context) and the research design you intend to use. The proposal serves two functions. First, the process of writing down the background for and design of your study helps you identify any missing elements. In presenting the reasoning behind your hypotheses, for example, you might find a gap in the logic underlying your derivation of the hypotheses from the theory that they are intended to test. Second, you can have other people read the proposal so that they can find any problems in background or design you might have overlooked. A fresh eye, unbiased by the researcher’s intense study of a topic, can bring a new, useful perspective to the research question, hypotheses, and design. How detailed you make the proposal depends on its purpose. A thesis or dissertation proposal (called a prospectus) will be highly detailed; a grant proposal or one that you prepare for your own use may contain less detail. In either case, any problems found in the research proposal must be dealt with by backing up in the process shown in Figure 5.1 until a resolution can be found.

Once you have validated your research proposal by ensuring that it is as problem-free as possible, you can begin your project. For now, let’s move on to some other issues surrounding research questions: replication research, designing research for utilization, and sources of bias in the hypothesis formulation process.

Replication—the repeating of experiments to determine if equivalent results can be obtained a second time—has an ambiguous status in science. On the one hand, scientists and philosophers of science extol the virtues of and necessity for replication; on the other hand, replication research that is actually conducted is held in low esteem and is rarely published (Neuliep & Crandall, 1990, 1993b). This section explains the two forms that replication research can take and their relation to replication’s ambiguous status in science, the implication of successful and unsuccessful replication research, and some issues to weigh when planning replication research.

Replication research can take two forms. Exact replication seeks to reproduce the conditions of the original research as precisely as possible, to determine if the results can be repeated. Exact replication is the less valued form of replication, being seen as lacking in creativity and importance and as adding little to the scientific knowledge base because it duplicates someone else’s work (Mulkay & Gilbert, 1986; Neuliep & Crandall, 1990). This bad reputation exists despite the fact that duplication performs an important function—it protects against error. Any research result that confirms a hypothesis has a specifiable probability of being wrong due to random error—the Type I error. However, the more often an effect is duplicated, the more confidence we can have in the validity of the results: It is unlikely that random error would cause the hypothesis to be confirmed every time the experiment was conducted. Flaws in research designs and procedures can also lead to incorrect results that should not hold up in a properly conducted replication. The importance of this error detection function is emphasized by the facts that researchers are eager to conduct exact replications when they suspect that there is a problem in the original research (Reese, 1999) and that replication studies are published when they demonstrate error (Neuliep & Crandall, 1990). Amir and Sharon (1990) present several examples of influential pieces of psychological research that subsequent researchers were unable to replicate; Reese (1999) discusses factors that could account for the partially successful and unsuccessful replications of Istomina’s (1948/1975) study comparing children’s memory in game contexts compared to lesson contexts.

The second form of replication research, conceptual replication, tests the same hypothesis (concept) as the original research, but uses a different setting, set of operational definitions, or participant population (Reese, 1999). The purpose of conceptual replication is to test the generalizability of research results, to see how well they hold up under new test conditions. For example, a principle that holds up well when a variety of operational definitions is used has a higher probability of being correct than one that can be demonstrated only under one set of operational definitions. The latter circumstance leads to the suspicion that the effect found in the original research was caused by some unique characteristic of the operational definitions rather than by the hypothetical constructs that the operational definitions were intended to represent. In addition, a principle that can be replicated in a variety of settings and with a variety of populations has a higher probability of being a general principle than does a principle limited to a specific set of conditions. We discuss the issue of generalizability in Chapter 8.

As shown in Table 5.2, replication research can have important implications for the principle being tested. These implications are functions of the type of replication conducted and whether or not the replication was successful in terms of obtaining results equivalent to those of the original research. A successful exact replication supports the principle being tested. Although the replication increases confidence that the principle is correct under the original test conditions, we don’t know how well the principle will perform under other circumstances. A successful conceptual replication both increases confidence that the principle is correct and extends knowledge of the principle’s applicability beyond the original test conditions. The greater the variety of conditions among a set of successful conceptual replications, the more widely applicable the principle.

Unsuccessful replications are less easy to interpret. The crux of the problem is that there is no way, given one study and one replication, of knowing where the error lies. Perhaps, as implied by the unsuccessful replication, the original study was flawed or suffered from a Type I error. However, it is also possible that the replication was flawed or suffered from a Type II error—incorrectly accepting the null hypothesis (Neuliep & Crandall, 1990). The original researchers may have underreported procedural details that could have influenced the results; if these procedures were changed in the replication, such as exact instructions or experimenter sex, this might account for the different results. For example, children’s attitudes toward the other sex depend on their age; if the original study omitted this information and the replication used younger respondents, this factor might account for the different results (Reese, 1999). Therefore, failed replications should themselves be replicated before we draw firm conclusions from them. With this caveat in mind, we can say that a failed exact replication damages the principle it tests, suggesting that the principle is not valid. A failed conceptual replication limits the principle’s generalizability. It shows that the principle doesn’t work under the conditions of the replication, but says nothing about the validity of the principle under the original research conditions or under any conditions in which it has not been tested.

Implications for the Principle Being Tested of the Success of the Replication and the Type of Replication

Result of Replication | ||

Type of Replication |

Successful |

Unsuccessful |

Exact |

Supports the principle |

Damages the principle |

Conceptual |

Supports and extends the principle |

Limits the principle |

Note: Adapted from Rosenthal and Rosnow, 2008, p. 112

Given the relatively low status of replication research among scientists and the possible difficulty of fitting the results of such research into the body of scientific knowledge, is it worth doing? Replications are worth doing and are quite frequently conducted, although conceptual replications are much more common than exact replications and replications are frequently conducted in conjunction with tests of new hypotheses, called replications and extensions (Neuliep & Crandall, 1993a). The greater frequency of conceptual replications and of replications and extensions is probably due to their ability to produce new information through generalization of the replicated principle and the testing of new hypotheses. The question, then, is not should you do replication research, but under what conditions should you do replication research? Two factors must be considered in answering this question: the importance of the hypothesis tested in the study you’re considering replicating and the amount of research already conducted on the hypothesis.

Importance of the hypothesis. The first consideration is the importance of the information you expect to gain from a replication. Replications are important to the extent that they test major hypotheses and can add new information about those hypotheses. As noted in the discussion of the characteristics of a good research question, the importance of a hypothesis is proportional to its importance to the theory from which it derives. Important hypotheses should be replicated when either of two conditions apply. The first condition is when there is reason to suspect a problem with the original research; a replication can be conducted to investigate this possibility. Two circumstances could lead to such a suspicion. First, someone could notice a possible alternative explanation for the results of the research. A replication can test the validity of that alternative explanation. For example, small-group researchers were once excited about a phenomenon called the “risky shift”: Decisions made about the best solution to a problem after a group discussion appeared to be riskier (that is, to involve a higher probability of incurring a loss) than individual decisions by group members prior to the discussion (see Myers & Lamm, 1976). However, because of the nature of the problems used in the research, most group members made initial choices that were slightly risky. Other researchers therefore decided to see what would happen with problems that led to relatively conservative (nonrisky) individual initial decisions. These researchers hypothesized that group decisions went in the same direction as the individual initial decisions but were more extreme; that is, slightly risky individual initial decisions led to riskier group decisions, but slightly conservative individual initial decisions would lead to group decisions that were even more conservative. This alternative hypothesis was confirmed, and the “risky shift” was shown to be a special case of the more general principle expressed in the alternative hypothesis.

The second circumstance that could lead to suspicion of a problem with the original research is that its results contradict or don’t fit in well with an established theory or principle. Although the logical positivist epistemology says that the validity of theories should be judged by the results of research, rather than judging the validity of research by its consistency with theory, the epistemology also says that theories should be judged by the weight of the evidence that bears on them. Therefore, if many studies support a theory and one does not, the inconsistent study is suspect. That study still deserves replication, however, because its nonconforming results might be due to some special feature of its design. If further research confirms the validity of the unsuccessful replication and shows that the failure to replicate was due to a specific aspect of the replication’s design, then that aspect represents a limitation of the theory. For example, a theory might do well in explaining some forms of aggression but not others.

The second condition for replicating an important hypothesis is to test its generalizability. This kind of replication is important because it helps define the boundary conditions of a theory—the circumstances under which it does and does not work. Research on cognitive dissonance theory, a classic theory in social psychology, provides an example of this process. As originally formulated (Festinger, 1957), the theory was relatively simple: If people perform actions that contradict their beliefs, they experience an unpleasant state called cognitive dissonance. People are motivated to reduce this unpleasantness; one way in which they can do so is by changing their beliefs to fit their behaviors. Replication research, however, has shown that this kind of belief change occurs only under a very narrow set of conditions (Cooper & Fazio, 1984). The effect of cognitive dissonance on belief change is limited by these boundary conditions.

Avoiding overduplication. The second consideration in planning a replication study is the amount of replication already done. Although replication research is valuable, one must avoid overduplication of well-established effects. That is, after a certain point, principles become well enough established that replication wastes resources. For example, discussing research on the use of tests of cognitive and perceptual abilities to predict job performance, Schmidt (1992) wrote that

as of 1980, 882 studies based on a total sample of 70,935 subjects had been conducted relating measures of perceptual speed to the job performance of clerical workers. … For other abilities, there were often 200–300 cumulative studies. Clearly, further research on these relationships is not the best use of available resources. (p. 1179)

Well-established effects should be replicated only if there is some strong reason to do so, such as the testing of alternative explanations or an important aspect of generalization. When is a principle well enough established not to require further replication? Unfortunately, there is no agreed-on answer to this question (Lamal, 1990), although journal editors do agree that a principle can reach the point of needing no further replication (Neuliep & Crandall, 1990). In the absence of objective criteria for determining how well established an effect is, perhaps the best indicator is consensus: If psychologists familiar with a topic believe that no further replication of an effect is needed, replication would probably not be useful.

Application is one of the three aspects of behavioral science, yet the results of behavioral science research are often not used in applied settings. In psychology, for example, few practicing psychotherapists see science or research as valuable tools for their clinical practice (Baker, McFall, & Shoham, 2008), and commentators in other areas of behavioral science also report low rates of use of research results (see Dempster, 1988; Ruback & Innes, 1988). This section examines two issues: the factors affecting knowledge utilization and the design of research for utilization.