Manifest Variables and Hypothetical Constructs

Reliability, Validity, and Measurement Error

Consistency across items within a measure

Choosing Among the Forms of Reliability

Categories of Validity Evidence

Relationships Among the Categories of Validity Evidence

Determining a Measure’s Degree of Validity

Assessing differential validity

Advantages of self-report measures

Limitations of self-report measures

Advantages of behavioral measures

Limitations of behavioral measures

Advantages of physiological measures

Limitations of physiological measures

Advantages of implicit measures

Disadvantages of implicit measures

Choosing a Measurement Modality

Locating and Evaluating Measures

Suggestions for Further Reading

Questions for Review and Discussion

A basic tenet of behavioral science is that people differ from one another, and one goal of behavioral science is to determine the causes and effects of these differences. To study why people differ, you must first be able to state the ways in which people differ (identify the important variables) and state the degree to which they differ on these variables. To study variables, you must first observe them (detect their presence) and then measure them (assign numbers to them that represent the degree to which they are present). Measurement consists of the sets of procedures we use to assign numbers to (to quantify) variables.

The process of quantification assists the research process in several ways. First, it lets you classify individuals and things into meaningful categories based on important characteristics, such as gender. For the sake of convenience, we refer to these characteristics as traits, although the term encompasses more than personality traits. Second, for some variables you can systematically arrange people or things on the basis of how much of the variable characterizes them. These processes of classification and arrangement let you find relationships between variables—to find, for example, whether Variable B is present most of the time that Variable A is present. Finally, using numbers lets you apply arithmetic processes to derive descriptive statistics, such as means and standard deviations that summarize the characteristics of groups of subjects and correlation coefficients that describe relationships between variables, and inferential statistics, such as the t-test and analysis of variance that assist in decision making.

Because of these contributions to the research process, one of the most important aspects of a research project is developing a measurement strategy, that is, deciding how to measure the variables of interest. When the variables are hypothetical constructs, the procedures used to measure them constitute their operational definitions, so the validity of the entire project hinges on the validity of the measurement strategy. This process of measurement consists of four steps:

This chapter deals with the second step. To help you develop a measurement strategy, we discuss three topics: reliability and validity in measurement, modalities of measurement, and the evaluation of measures.

Reliability and validity are two of the most basic and most important aspects of measurement. This section begins by explaining the distinction between manifest variables and hypothetical constructs, then explains how the degree of reliability and validity of measures of hypothetical constructs are affected by measurement error, discusses how to assess the reliability and validity of measures, and concludes with a brief introduction to reliability and validity issues in cross-cultural research.

We can measure only what we can observe. We can, however, observe many things: the physical characteristics of people and objects, behavior, physiological responses, answers to questions, and so forth. Such variables, which we can directly observe, can be called manifest variables to distinguish them from hypothetical constructs, which we cannot directly observe. The problem, of course, is that behavioral scientists are frequently interested in measuring hypothetical constructs because many variables that behavioral science deals with are hypothetical constructs. As noted in Chapter 1, we use operational definitions, which consist of manifest variables, to represent hypothetical constructs in research. In doing so, we assume that the hypothetical construct is causing the presence and strength of the manifest variable used as its operational definition. For example, we assume that a certain personality characteristic, such as hostility, causes people to behave in certain ways. We therefore assume that the presence and strength of the manifest variable reflects, albeit imperfectly, the presence and strength of the hypothetical construct. Consequently, we infer the strength of the hypothetical construct (such as a person’s level of hostility) from the strength of the manifest variable (such as the way the person acts or how the person answers questions about hostile behavior). By measuring the manifest variable, we measure the hypothetical construct; we therefore consider the manifest variable to be a measure of the hypothetical construct.

These inferences present a problem for measurement: How much confidence can you have that your inference about the relationship between the operational definition and the hypothetical construct is correct? Measurement theorists developed the concepts of reliability and validity as means of checking the adequacy of measures as indicators of hypothetical constructs. These concepts are the principal topics of this section.

However, we are not always interested in manifest variables as measures of hypothetical constructs; sometimes we are interested in manifest variables for their own sake. We might be interested, for example, in whether men and women express different opinions on a political issue. We can directly observe people’s gender and their answers to questions on the political issue, which constitute their opinions. We can then examine gender differences in response to the questionnaire items to answer our question. At no point do we make inferences about hypothetical constructs. Problems can arise, however, because manifest variables can be used as measures of constructs. We might be tempted, for example, to assume that certain opinions represent conservative political attitudes and that other opinions reflect liberal political attitudes, and conclude that, say, women are more politically liberal than men because their opinions differ. However, unless evidence shows that these opinions accurately represent the hypothetical construct of political orientation, we have no way of knowing whether our conclusion about gender differences on this construct is correct. It is therefore essential to maintain an awareness of the distinction between the use in research of manifest variables for their own sakes and their use as operational definitions of hypothetical constructs, and to draw the proper conclusions based on how they are used.

The concepts of reliability and validity are distinct but closely related. This section defines reliability and validity and shows how they are related through the concept of measurement error.

Reliability and validity. The reliability of a measure is its degree of consistency: A perfectly reliable measure gives the same result every time it is applied to the same person or thing, barring changes in the variable being measured. We want measures to be reliable—to show little change over time—because we generally assume that the traits we measure are stable—that is, that they show little change over time. For example, if you measure someone’s IQ as 130 today, you expect to get the same result tomorrow, next week, and next month: IQ is assumed to be stable over time. As a result, an IQ measure that gave radically different results each time it was used would be suspect: You would have no way of knowing which score was correct.

The validity of a measure is its degree of accuracy: A perfectly valid measure assesses the trait it is supposed to assess, assesses all aspects of the trait, and assesses only that trait. Bear in mind that the validity of a measure is relative to a purpose; that is, a measure can be valid for one purpose but not for another. The fMRI, for example, does an excellent job at its intended purpose of measuring changes in brain activity, but using this measure to determine whether a person is telling the truth, a purpose for which it was not designed but is sometimes used, remains highly questionable (Wolpe, Foster, & Langleben, 2005). Although reliability and validity are distinct concepts, they are closely related. An unreliable measure—one that gives very different results every time it is applied to the same person or thing—is unlikely to be seen as accurate (valid). This inference of low validity would be correct, although, as shown later, high reliability is no guarantee of validity. The link between reliability and validity is measurement error.

Measurement error. When we measure a variable, we obtain an observed score—the score we can see. The observed score is composed of two components: the true score (the actual degree of the trait that characterizes the person being assessed) and measurement error (other things that we did not want to measure, but did anyway because of the imperfections of our measuring instrument). There are two kinds of measurement error. Random error fluctuates each time a measurement is made; sometimes it’s high and sometimes it’s low. As a result, the observed score fluctuates; sometimes the observed score will be higher than the true score, and sometimes it will be lower. Therefore, random error leads to instability of measurement and lower reliability estimates. Random error can result from sources such as a person’s being distracted during the measurement process; mental or physical states of the person, such as mood or fatigue; or equipment failures, such as a timer going out of calibration. Systematic (nonrandom) error is present every time a measurement is made. As a result, the observed score is stable, but inaccurate as an indicator of the true score. Systematic error can result from sources such as poorly worded questions that consistently elicit a different kind of response from the one intended, or an instrument’s measuring traits in addition to the one it is intended to measure.

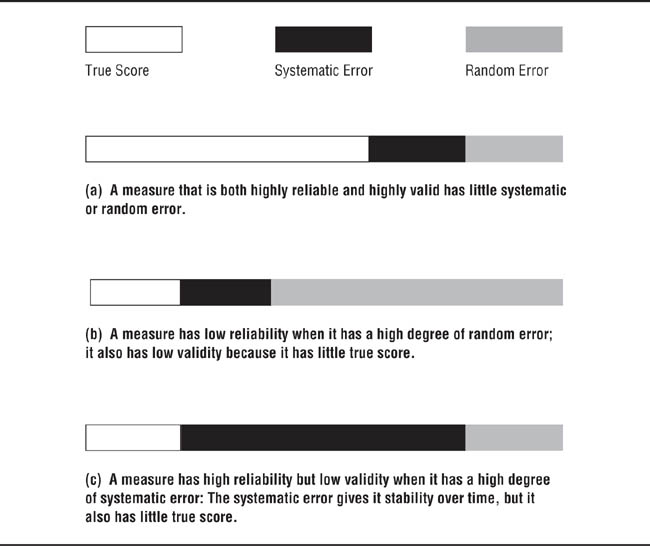

The effects of random and systematic error on reliability and validity are illustrated in Figure 6.1, with the bars indicating observed scores. Figure 6.1(a) represents a valid, reliable measure: It has a very high proportion of true score and relatively little error of either kind. Figure 6.1(b) represents an unreliable measure: It is mostly random error. Note that as a result of its large proportion of random error, the measure has relatively little true score; it is therefore of low validity. Figure 6.1(c) represents a measure that is reliable but is of low validity. Its reliability stems from its being composed mostly of systematic (stable) error and very little random (unstable) error. However, it also has very little true score, and so is of low validity. Figure 6.1 carries an important implication: An unreliable measure always has low validity, but high reliability does not guarantee high validity. It is therefore not enough to know that a measure is reliable before using it; you must also have evidence for its validity.

Reliability, Validity, and Measurement Error.

When you judge a measure’s degree of reliability, you must first decide which of several forms of reliability estimates is appropriate for the measure and then decide whether the measure has adequate reliability. This section describes the forms that reliability estimates can take, discusses the factors to weigh in choosing an appropriate form of reliability assessment for a measure, and explains the standards used to judge the adequacy of a measure’s reliability.

The term reliability refers to consistency, which can be assessed in three ways: across time, across different forms of a measure, and, for multi-item measures, across items.

Consistency across time. Consistency of scores across time is an indicator of reliability because we assume that the traits we want to measure are relatively stable across time; therefore, measures that have a high degree of true score should also be stable across time. Consequently, one way of assessing reliability, referred to as test-retest reliability,is to assess people’s scores on a measure on one occasion, assess the same people’s scores on the same measure on a later occasion, and compute the correlation coefficient for the two assessments; that correlation coefficient represents the degree of reliability shown by the measure. Note that the concept of reliability does not require that people’s scores be exactly the same on both occasions; random error makes this outcome unlikely. All that is required is that people’s scores fall in generally the same rank order: that people who score high the first time also score high the second time and that people who score low the first time also score low the second time. How much time should elapse between the two assessments? The answer depends on the trait being assessed. Some traits, such as mood, are assumed to be highly changeable, whereas others, such as adult IQ, are assumed to be relatively stable for most of a lifetime. The assumed stability of most traits falls somewhere between these two. One should therefore use a time period over which it is reasonable to assume that the trait will be relatively stable. This time period can be derived from the theory that defines the trait or from research on the trait.

Consistency across forms. Consistency across different forms of the same measure can be used as an indicator of reliability when a measure has two or more versions or forms that are designed to be equivalent to one another (referred to as alternate forms).; that is, each form is designed to give approximately the same score for any person. Measures having several forms can be very useful when you want to assess people at short intervals but don’t want to bias their responses by using the same questions each time. Because each form is designed to measure the same trait in the same manner, alternate forms reliability can be assessed as the correlation between scores on the two forms. Sometimes the measuring instruments used are people; for example, two observers watch children at play and rate how aggressive each child is on a 7-point scale. In this case, the reliability of this measure of aggression can be assessed by correlating the ratings of the two raters to obtain their interrater reliability.

Interrater reliability can also be assessed when the rater puts behavior into categories (such as aggressive or nonaggressive) rather than rating the behavior on a quantitative scale. In such cases, you can assess reliability in terms of the percentage of times the raters agree on the category in which each observed behavior goes. However, be careful to consider the likelihood of agreements occurring by chance when evaluating reliability in this way. For example, if only two categories are used, raters would agree 50% of the time if they categorized behaviors by flipping a coin, with heads meaning one category and tails the other. A statistic called Cohen’s kappa (Cohen, 1968) provides an index of agreement that is corrected for chance and that can be interpreted in the same way as a correlation coefficient.

Consistency across items within a measure. Consistency among items within a measure can be used as an indicator of reliability when a measuring instrument uses multiple items or questions to assess a trait, with the sum of a person’s scores on the items being the total score for the measure. Most standardized tests and many research measures are constructed in this manner. Because each item is designed to assess the same trait, the reliability of the measure can be assessed in terms of the correlations among the items. A simple way to accomplish this is to split the items into two parts and compute the correlation between the respondents’ total scores on the two parts; this is referred to as split-half reliability. More generally, one could look at the pattern of correlations among all the items. The most common example of this approach is called Cronbach’s alpha. Alpha is a function of the mean correlation of all the items with one another and can be interpreted like a correlation coefficient. Because they assess the degree to which responses to the items on a measure are similar, split-half correlations and Cronbach’s alpha are considered indicators of the internal consistency of measures. Because Cronbach’s alpha is the most commonly reported internal consistency coefficient (John & Soto, 2007), it is important to be aware of its limitations. Three of the most important of these limitations are discussed in Box 6.1.

When researchers report the reliability of the measures they use, the reliability coefficient that is cited most often is Cronbach’s alpha (John & Soto, 2007). Because alpha is so popular, John and Soto note that it is important to bear some of alpha’s limitations in mind. First, although alpha is a way of indexing a measure’s internal consistency, a high alpha value does not mean that a measure is unidimensional. Because of the way in which the alpha coefficient is calculated, a scale could assess more than one dimension of a construct and still produce a reasonably high alpha coefficient. The dimensionality of a scale must be assessed a statistical technique called factor analysis, which we discuss in Chapter 12.

A second limitation of alpha is that if the items on a scale are essentially synonyms of one another, the scale’s alpha value will be artificially high. The concept of using scales that consist of multiple items (discussed in more detail in Chapter 15) is that each item captures a somewhat different aspect of the construct being measured, so scale items should be related to one another but not conceptually identical. For examples items such as “I am afraid of spiders” and “Spiders make me nervous” (John & Soto, 2007, p. 471) are too similar to be used on the same scale, although each might be useful on separate versions of a measure having alternate forms.

Finally, the value of alpha for a scale increases as the number of items on the scale increases, assuming that all of the items are relevant to the construct being measured (see the section on content validity later in this chapter). Although the relationship between the value of alpha and scale length might tempt researchers to create very long scales, John and Soto (2007) note that there are drawbacks that accompany the use of long scales. For example, long scales might result in respondent fatigue that could cause them to be careless in their responses to scale items. In addition, increasing the number of items beyond 20 does not substantially increase the scale’s alpha value. Finally, a short scale might have a somewhat low alpha value but still perform well on other indicators of reliability such as test-retest coefficients. For example, Rammstedt and John (2007) created 2-item versions of widely-used personality scales and found that although the alpha values of these scales were very low, their test- retest coefficients averaged a respectable .75. In addition, the correlations between scores on the short and long versions of the scales averaged r = .83, proving evidence that the shorter scales were valid as well as reliable.

In summary, then, when interpreting a scale’s alpha coefficient

• |

Do not assume that a high value for alpha indicates that the scale is unidimensional; seek separate, more appropriate evidence of dimensionality. |

• |

Watch out for scales that contain synonymous items; those scales’ alpha values may be artificially high. |

• |

For short scales that have low to moderate alpha values, take other evidence of reliability, such as test-retest correlations, into consideration. |

Which form of reliability assessment is the best? As for most questions in behavioral science, there is no single answer. Sometimes the decision is driven by the choice of measure; for example, measurement by raters requires the use of some form of interrater reliability. Because we’re trying to assess the stability of measurement, test-retest is probably the ideal form of reliability assessment. However, some traits, such as mood, are not stable across time; internal consistency might provide a better estimate of reliability in such a case. In other cases, it might not be possible to test people more than once, again leading to the use of internal consistency reliability. Fortunately, the internal consistency of a measure is reasonably well related to its stability across time (Schuerger, Zarrella, & Hotz, 1989).

How large should a reliability coefficient be to be considered good? There are no absolute rules, but Robinson, Shaver, and Wrightsman (1991a) suggest a minimum internal consistency coefficient of .70 and a minimum test-retest correlation of .50 across at least a 3-month period, and Bakeman and Gottman (1989) suggest a minimum kappa of .70 for interrater reliability. Higher reliability coefficients and high test-retest correlations across longer intervals indicate better reliability. However, when comparing the relative reliabilities of several measures when the reliability of each is assessed in a separate study, it is important to remember that several factors can affect the magnitude of the reliability coefficient found for any one measure in any one study. For example, test-retest correlations tend to decrease as the test-retest interval increases, and the scores of older respondents tend to show greater temporal stability than do those of younger respondents (Schuerger et al., 1989). Therefore, the evaluation of a measure’s reliability must consider the effects of the characteristics of the reliability study. Two measures that would have the same reliability coefficient when assessed under the same circumstances might have different coefficients when assessed under different circumstances. Just as a person’s observed score on a measure is an imprecise indicator of his or her true score on the trait, the reliability coefficient found in any one study is an imprecise indicator of the measure’s true reliability; true reliability is better indicated by a measure’s mean reliability coefficient across a number of studies. In addition, the test-retest coefficient of any measure is going to reflect the natural degree of stability or instability of the trait; that is, measures of more labile traits, such as mood, will have lower test-retest coefficients than measures of more stable traits. Therefore, what constitutes a good stability coefficient for a labile trait, such a mood, might be a poor coefficient for a more stable trait, such as IQ.

The term validity refers to the accuracy of measurement; that is, it addresses the question of how confident we can be that a measure actually indicates a person’s true score on a hypothetical construct or trait; the answer to this question reflects the construct validity of the measure (John & Soto, 2007). The concept of validity has six important aspects (Gronlund, 1988, p. 136):

Researchers are not really interested in the properties of tests. Instead, they are interested in the attributes of people who take those tests. Thus, validation processes are not so much directed toward the integrity of tests as they are directed toward the inferences that can be made about the attributes of the people who have produced the test scores. (p. 1186)

However, as a matter of tradition and convenience, we usually refer to the validity of a measure rather than to the validity of the conclusions drawn from it. |

|

6. |

“Validity is a unitary construct.” Earlier conceptions of validity considered the types of validity evidence to be distinct forms of validity. The current view of validity, in contrast, is that validity is a single concept that has several categories into which we can place evidence for or against a measure’s validity. |

As we noted earlier, there are five types or categories of evidence that can be used to support the validity of a measure: generalizability, content validity, structural validity, external validity, and substantive validity. Let’s examine each of them.

Generalizability. The generalizability aspect of construct validity refers to the extent to which a measure provides similar results across time, research settings, and populations. For example, test-retest coefficients provide evidence that scores on a test are similar across time: People get roughly the same score every time they respond to the measure. A measure should show evidence of reliability and validity across various populations such as women and men, age cohorts, and racial and ethnic groups. Measures that have demonstrated reliability and validity across groups permit one to draw valid conclusions from intergroup comparisons; without such evidence conclusions drawn about group similarities or differences may not be valid (Chen, 2008).

Content validity. Content validity consists of demonstrating that the content of a measure—for example, the items on a questionnaire—adequately assesses all aspects of the construct or trait being measured. Adequate assessment has two characteristics: The content of the measure must be both relevant to the trait and representative of the trait. Relevance and representativeness are judgments based on the nature of the trait as defined by the theory of the trait. A relevant measure assesses only the trait it is attempting to assess, and little else. If a trait has more than one aspect, a representative measure includes all aspects. Perhaps the clearest examples of these concepts come from academic tests. Relevant test items ask only about the material the test is supposed to cover, not about other material. For example, a question about how to compute a t-test would not be relevant to students’ knowledge of social psychology, although it would be relevant to their knowledge of statistics. Representative test items sample all the topics that the test is supposed to cover. For example, if a test covers three chapters of a textbook, each of which received equal emphasis in the course, the principle of representativeness requires that the test contain questions on each chapter, not just one or two, and that each chapter have equal weight in determining the overall test score.

The measurement of self-esteem provides an example from the realm of psychological assessment. If we define self-esteem as self-evaluation, an item such as “I’m less competent than other people” would be more relevant than an item such as “I prefer Chevrolets to Fords.” In terms of representativeness, we might divide self-esteem into components such as global self-evaluation, self-evaluation relative achievement situations, and self- evaluation relative to social situations (Wylie, 1989), and include items that assess each component. We would also want to determine, on the basis of the theory of self-esteem we are using to develop the measure, how much importance each component should have in forming an overall self-esteem score. For example, should each component contribute equally to the overall score or should some components carry more weight than others? The degree to which a measure provides evidence of content validity can be represented quantitatively as a function of the proportion of expert judges who, given a definition of a trait, agree that each item on a measure is relevant to the trait and that the measure represents all components of the trait (Lawshe, 1975).

Structural validity. Structural validity refers to the dimensionality of a measure. Scores on a measure of a unidimensional construct should produce a single dimension when subjected to factor analysis, a statistical technique for assessing the dimensionality of measures (see Chapter 12). Similarly, scores on measures of multidimensional and multifaceted constructs should produce as many dimensions or facets as the theory of the constructs says the construct is composed of.

External validity. So far, our discussion has dealt with characteristics that are internal to a measure in the sense that they focus on relationships that exist within the measure: how well scores replicate (generalizability), the item content of the measure, and how the items on a measure relate to each other (structural validity). The external validity of a measure addresses the question of how well scores on a measure correlate with relevant factors or criteria outside, or external to, the measure such as scores on criteria that are conceptually relevant to the to construct being measured. Note that the term external validity is also used to refer to the extent to which one obtains similar research results across participant populations, research settings, and other study characteristics. We discuss this different form of external validity in Chapter 8.

The criteria for assessing external validity of a measure are chosen based on the theory that underlies the construct being measured, which should specify the ways in which the construct being measured is related to other constructs and the ways in which people who differ on the construct should behave. To the extent that people who score differently on a measure of a construct show traits and behaviors consistent with the theory, evidence for the validity of the measure exists. Therefore, there are three steps to the process of collecting evidence of the external validity of a measure (Zeller & Carmines, 1980): (1) formulating hypotheses that represent the links between the construct being measured and other constructs and behaviors specified by the theory of the construct; (2) conducting a study to determine the empirical relationships between the measure being evaluated and measures of the other constructs and behaviors; and (3) interpreting the empirical evidence in terms of the degree to which it provides evidence of construct validity.

Using this paradigm, the external validity of a measure can be investigated relative to four types of criteria. One criterion is the extent to which scores on the measure being investigated correlate with scores on well-validated measures of the same construct: If all the measures are tapping the same construct, scores on them should be correlated. A second, related, criterion is the extent to which scores on the measure being investigated correlate with scores on measures of related constructs. That is, the theory of the construct being measured probably postulates that the construct is related to other constructs; therefore scores on the measure should be related to scores on well-validated measures of those related constructs.

Note the emphasis on using well-validated measures as criteria for external validity. Whenever a criterion used in the study of the external validity of a measure is a measure of a hypothetical construct, we must take the construct validity of the criterion measure into account when drawing conclusions about the validity of the measure being tested (Cronbach, 1990). The more evidence there is for the construct validity of the criterion measure, the more confidence we can have in the external validity of the measure being tested. Consider the situation in which we are testing the external validity of a new measure of self-esteem. One way to do that would be to correlate the scores on the new measure of self-esteem with the same people’s scores on an existing measure. However, if the existing measure is not itself of high validity (that is, it is not actually measuring self-esteem), the correlation between scores on that measure and scores on the new measure tells us nothing about how well the new measure assesses self-esteem. Therefore, when testing the external validity of a new measure by correlating scores on it with scores on criterion measures, it is essential the at the criterion measures exhibit a high degree of construct validity.

In addition to correlating scores on a measure with scores on other measures, a third way to assess the external validity of a measure is to use the contrasted groups approach. If the theory of a trait indicates that members of different groups should score differently on a measure, then the mean scores of members of those groups should differ. For example, we would expect people in the helping professions to score higher on a measure of empathy than people in other professions. Conversely, we would expect criminals to score lower than non-criminals.

Finally, one would expect scores on a measure to predict behaviors that are related to the trait being measured. For example, many theories of prejudice hold that prejudiced people prefer to avoid contact with members of groups against which they are prejudiced. Thus, one would expect that if a measure of prejudice were valid, people who score high on the measure should show more avoidance than people who score low on the measure. Thus, Sechrist and Stangor (2001) found that White people who scored high on a measure of racial prejudice kept an average of four chairs between themselves and an African American when asked to take a seat in a waiting room whereas White people who scored low kept an average of two seats between themselves and an African American.

Substantive validity. Substantive validity consists of “testing theoretically derived propositions about how the construct in question should function in particular kinds of contexts and how it should influence the individual’s behavior, thoughts, and feelings” (John & Soto, 2007, p. 482). That is, if a measure is valid, people who score differently on a construct should respond to situational variables such as experimental manipulations in ways predicted by the theory of the construct. For example, Altemeyer’s (1998) theory of right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) holds that people who score high on this trait should be more willing to follow an authority figure’s instructions to perform a behavior that would harm a member of an outgroup than would people who score low on the construct. Petersen and Dietz (2000) tested this hypothesis by having research participants who scored either high or low on a measure of RWA play the role of a personnel manager. They were instructed to choose three candidates for a managerial position; half the candidates whose application materials they reviewed were from the participants’ ingroup and half from an outgroup. In addition, before making their choices, all participants read a memo from the company president; half the participants read a generalized “pick the best candidates” memo and the other half read a memo that discouraged hiring members of the outgoup. The results showed that, consistent with the theory, participants low in RWA did not discriminate between members of the ingroup and the outgroup; however, those high in RWA discriminated when the company president approved of discrimination but not when he did not.

As John and Soto (2007) point out, and as illustrated by this example, tests of the substantive validity of a measure and tests of the theory underlying the measure are inextricably linked. If the hypotheses of a study are supported by the data collected, those results provide evidence for the validity of both the theory and the measure. What should we conclude if a particular validation study does not find such evidence? One possible conclusion is that the measure is not valid. There are, however, three alternative explanations (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955). The first, and easiest to check, is that an inappropriate or inadequate method was used to test the hypotheses that were intended to provide evidence of validity. The methodology can be reviewed for flaws. A second alternative explanation is that the theory of the construct is wrong, predicting a relationship that is nonexistent. The tenability of this explanation depends on the state of the theory: It is less likely to be true of a well-tested theory than of a new theory. Finally, it is possible that the measure of the trait with which the new measure was expected to correlate lacks validity; for example, a failure to find a correlation between a new measure of self-esteem and a measure of feelings of control might be due to an invalid measure of feelings of control rather than to an invalid measure of self-esteem. The tenability of this explanation depends on the state of the evidence for the validity of the other measure. We should therefore not be too quick to reject the construct-related validity of a measure on the basis of a single test; conclusions of both low and high evidence for validity should be drawn only on the basis of a body of research.

So far, this discussion of validity has focused on what Campbell and Fiske (1959) refer to as convergent validity, the extent to which evidence comes together, or converges, to indicate the degree of validity of a measure: that is, evidence that lets us conclude the measure is assessing what it is designed to assess. An equally important aspect of validity is what Campbell and Fiske named discriminant validity, evidence that a measure is not assessing something it is not supposed to assess. For example, a measure designed to assess shyness, but that also assesses anxiety, lacks discriminant validity relative to anxiety. The measure’s lack of discrimination between shyness and anxiety makes it difficult to determine the extent to which high scores on the measure represent high shyness, high anxiety, or some combination of both high anxiety and high shyness. Although most discussions of discriminant validity tend to focus, as does this shyness and anxiety example, on construct validity, the concept is also related to content validity. As already seen, the content of a measure should reflect the trait to be assessed and only the trait to be assessed; to the extent that a measure is high in relevance, it will show high discriminant validity.

As an aspect of construct validity, discrimination is evaluated by considering the measure’s correlation with variables that the theory of a construct postulates to be irrelevant to that construct. A low correlation with an irrelevant variable is evidence for discriminant validity. Irrelevant variables can be of two forms. Substantive variables are other constructs that might be measured along with the construct of interest. For example, because a paper- and-pencil IQ test might measure reading ability along with IQ, it would be desirable toshow that reading ability scores were uncorrelated with scores on the IQ measure. Method variables concern the manner by which a construct is assessed, for example, by self-report or behavioral observation. A person’s score on a measure is partially a function of the assessment method used, which is one form of systematic measurement error (Campbell & Fiske, 1959). For example, scores on self-report measures of two traits could be correlated because people have an extremity response bias—a tendency to use only the high or low end of a self-report scale—rather than because the traits are related to one another.

A common method for assessing discriminant validity is the multitrait-multimethod matrix, or MTMMM (Campbell & Fiske, 1959). The MTMMM consists of the correlations between several constructs that are unrelated in theory (usually at least three), each measured by several different methods, with the number of methods usually equaling the number of constructs. Let’s say that you wanted to do a validation study of a new self- esteem measure. Your theory says self-esteem should not be correlated with loneliness and shyness. You could measure each of the three traits in three different ways—self-report, ratings by friends, and behavioral observation—and calculate the MTMMM, which consists of the correlations among the nine variables. The MTMMM provides three types of information:

1. |

High correlations among measures of the same construct using different methods provide evidence for the convergent validity of the measures. Because of the different methods, none of the correlations are due to the type of measure being used. |

2. |

Low correlations among measures of different constructs using the same method indicate good discriminant validity on the basis of method. Even when the same measurement method is used (which should increase correlations), the correlations are low, indicating that the measures are assessing different traits. |

3. |

High correlations among measures of different constructs using different methods indicate a lack of distinctiveness among the constructs. Even when different methods are used (which should minimize correlations) the correlations are high, indicating that the constructs are similar. That is, even though the theory says that the constructs (say, shyness and self-esteem) are different, the evidence says they are essentially similar: One concept may have been given different names. |

Trochim (2006) presents a detailed explanation of the MTMMM. The MTMMM itself provides no statistical test of the degree of either convergence or discrimination; however, the matrix can be analyzed using additional statistical techniques that provide such tests (e.g., Byrne, 2010; Schumacker & Lomax, 2004).

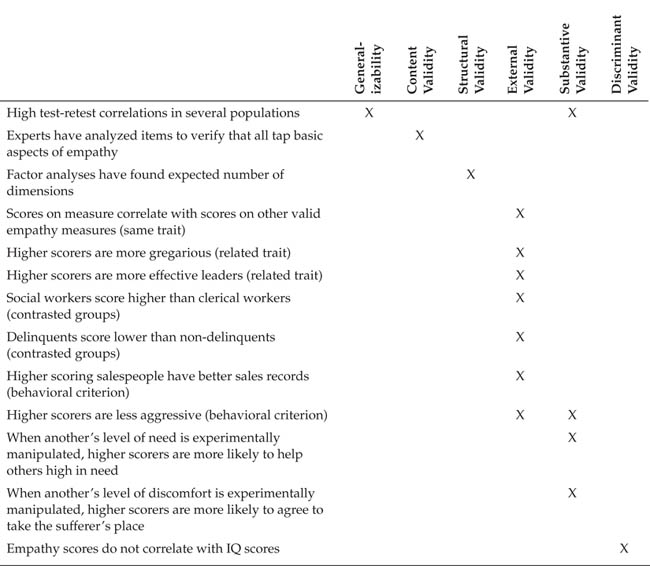

Now that we have examined the categories of validity evidence separately, it is time to reemphasize that all three categories represent one concept: validity. As a result, the different categories are related to and reinforce one another. For example, measures that have a high degree of relevant and representative content should also do well at predicting theoretically relevant behaviors and should show good convergence and discrimination relative to measures of other constructs. Evidence that a measure accurately predicts behavior is also evidence of substantive validity when the theory of the construct predicts the behavior being assessed. Table 6.1 presents an example of how all categories of evidence can be brought together to support the validity of a measure of empathy.

Examples of Possible Validity Evidence for a Measure of Empathy

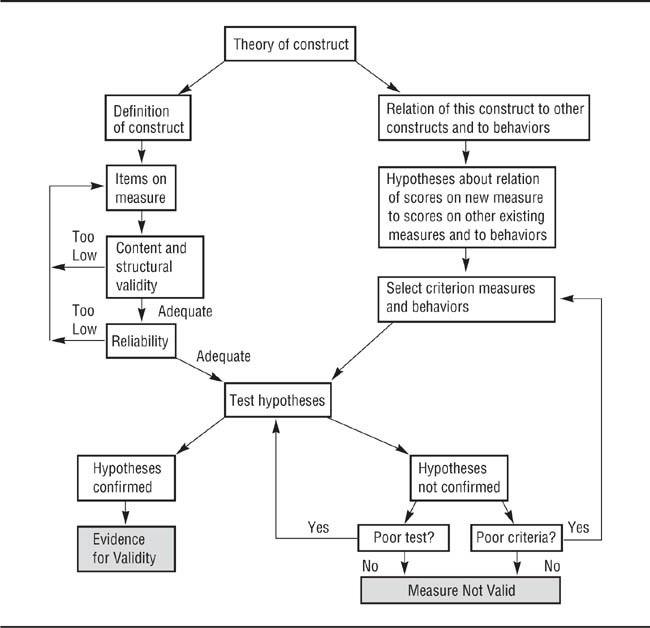

Let us summarize this discussion of reliability and validity by taking a brief look at the process of determining a measure’s degree of validity; more detailed discussions appear in DeVellis (2003) and Spector (1992). As Figure 6.2 illustrates, the development of a measure starts with the theory of a construct. The theory defines the construct and states the ways in which it should be related to other constructs and behaviors; ideally, the theory also states the constructs and behaviors that its trait should not be related to. A well-specified theory clearly spells out these definitions and relationships.

Given the definition of the construct, the developers of the measure select items they think will measure it. These items can be statements that respondents can use to rate themselves or others, criteria that observers can use to rate or describe behaviors they observe, or physiological responses. For example, a theory of self-esteem might define self-esteem in terms of self-evaluation. A self-rating item might therefore be something like “I am at least as smart as most people”; observers might be asked to record the number of positive and negative comments a person makes about him- or herself during a given period of time. In either case, the developers of the measure will ensure that the items are relevant to the construct and represent all aspects of the construct as defined by the theory (content validity). The items in the set are then rated on their relevance and representativeness by outside experts as a check on the measure’s content validity. If this evidence suggests that the measure’s degree of content validity is too low, the item set must be revised until the measure attains adequate content validity. The measure’s reliability can then be checked for both internal consistency and stability over time. If these checks indicate that the degree of reliability is not adequate, the developers must revise the item set until it attains an adequate degree of reliability.

The Measure Validation Process.

Items are selected and validates, reliability is assessed, validity-relevant hypotheses are formulated, and the hypotheses are tested.

Concurrently with these processes, the developers analyze the theory of the construct to determine the relationships to other constructs and behaviors that the theory proposes for the construct. These propositions are turned into hypotheses, such as “Our new measure of self-esteem will have large positive correlations with other valid measures of self-esteem, small to moderate negative correlations with valid measures of anxiety and depression, and zero to small correlations with measures of shyness. In addition, when people who score low on our measure of self-esteem experience failure on an experimental task, they will be more likely to blame themselves for the failure than will people who score high on the measure.” With the hypotheses set, the developers can select appropriate criterion measures and experimental procedures to test the hypotheses.

The developers then test the hypotheses and evaluate the results of the tests. If the hypotheses are confirmed, the developers have evidence for the validity of their measure. If the hypotheses are not confirmed, the developers must reexamine the adequacy of their research procedures and criterion measures. If both are good, the evidence suggests that the measure has low validity for assessing the trait. If one or both are weak, then the developers must improve them and retest their hypotheses.

Differential validity exists when a measure is more valid for assessing a construct for members of one group than for members of another group; that is, it assesses more of the true score for members of one group than for members of another group. For example, an IQ test might be highly valid for one cultural group but less valid for a different cultural group. When a measure exhibits differential validity, research based on the measure is more valid for the group for which the measure is more valid; conclusions drawn about members of the other group on the basis of the measure are less valid and therefore biased. Differential validity has two sources. One source is differential content validity. If the content of a measure is more relevant to members of one group than to members of another group, the measure will be more valid for the first group. For example, many questions used in mathematics achievement tests during the 1970s based their problems on situations more familiar to boys than to girls (Dwyer, 1979), such as the computation of baseball batting averages. This differential content validity might be one reason why boys scored higher than girls on these tests even though girls received higher math grades in school. Differential validity can also occur when the trait being assessed takes different forms in different groups, but the measure assesses only one form of the construct. Sternberg (2004), for example, argues that successful intelligence is defined differently by different cultures; therefore, measures designed to assess successful intelligence in the United States may have different psychological meaning in India or Tanzania. A test of, for example, abstract reasoning may be valid in one culture, but invalid in another. Hence, IQ tests developed in one culture cannot simply be translated into another language and used as a valid measure in another culture.

The cross-cultural context. Differential validity is an especially problematic issue in cross- cultural research and raises a number of issues that one must take into consideration when conducting or evaluating such research (Matsumoto, 2000). One problem that can arise is that a concept that exists in one culture does not exist or takes a different form in another culture, making cross-cultural comparisons inaccurate or impossible. For example, Rogler (1999) noted that although the Native American Hopi culture recognizes five forms of the psychological disorder of depression, only one of those forms is similar to depression as assessed by diagnostic measures commonly used in mental health research. Rogler pointed out that one consequence of this difference is that “reliance on [standard measures] would have overlooked most of the depressive symptoms among the Hopis” (p. 426).

Another potential problem is that items on a measure may have different meanings in different cultures. Greenfield (1997), for example, related the experience of a group of American researchers working in Liberia who asked members of the Kpelle tribe to sort objects into pairs of related objects. The objects used included food items and tools. Instead of giving the “right” answer (from the researchers’ perspective) by pairing objects based on the researchers’ abstract conceptual categories, they paired the items functionally, such as by putting a knife with a potato because a knife is used to cut potatoes. The research participants justified their pairings by explaining that that was how a wise person would do it. When the researchers asked how a foolish person would make the pairings, they sorted the objects in the American way, by abstract category such as food items and tools. “In short, the researchers’ criterion for intelligent behavior was the participants’ criterion for foolish; the participants’ criterion for wise behavior was the researchers’ criterion for stupid” (Greenfield, 1997, p. 1116).

A third source of problems in cross-cultural measurement is translation of measures. An Italian proverb says that “Translation is treason,” recognizing that translations can rarely, if ever, convey an exact meaning from one language to another. Nonetheless, cross- cultural research is often cross-language research, so translations are often necessary. Rather than listing all the potential problems in translation (see, for example, Knight, Roosa, & Umaña-Taylor, 2009), we will note only a few. Rogler (1999), pointed out that one problem in translation is the use of idioms in measures. For example, in American English we often refer to feelings of sadness or depression as “feeling blue,” and that term is used in items on some widely-used measures of depression. However, Rogler noted that “azul, the color blue, … makes no sense in Spanish as a descriptor of mood” (p. 428).

False cognates—words in different languages that sound alike but have different meanings or connotations—can also be a problem. Greenfield (1997) gives the example of the English word education and the Spanish word educación: “the [cultural] meaning of educación is not the same as education. The social skills of respectful and correct behavior are key to educación; this contrasts with the more cognitive connotations on the English word education” (p. 1117). Such differences in meaning can have important consequences:

When children of Latino immigrant parents go to school [in the U.S.], the [Latino] emphasis on understanding rather than speaking, on respecting the teacher rather than expressing one’s own opinions leads to negative academic assessments [by Anglo teachers] who equated [not speaking up in class] with having a bad attitude…. Hence, a valued mode of communication in one culture—respectful listening—became the basis for a rather sweeping negative evaluation in the school setting where self-assertive speaking is the valued mode of communication. (p. 1120)

Assessing differential validity. There are four ways in which validation research can indicate that a measure might be differentially valid. First, group means on the measure might differ when the theory of the construct predicts no such differences. Using the measure under these circumstances could lead to the erroneous conclusion that one group is superior to another on the trait. A second indicator of possible differential validity is finding different correlations with measures of the same construct for different groups. For example, a new measure of self-esteem that had a correlation of .60 with another well-validated measure of self-esteem for men but a correlation of .01 for women is probably valid only for men. Its use with women would lead to erroneous conclusions. Third, a similar situation could arise for correlations with measures of related constructs: a high correlation with the criterion for one group, but a low correlation with the criterion for another. Finally, if experimental validity studies find different outcomes for different groups and those differences are not predicted by the theory, this could indicate differential validity.

The extent of the problem. How big a problem is differential validity? In the United States, this question has been explored most extensively for ethnic group differences in the ability of employment selection tests to predict job performance. Systematic reviews of those studies indicated that differential validity was not a problem in that context (for example, Schmidt, Pearlman, & Hunter, 2006). However, this research says nothing about other aspects of validity for those measures or the possible differential validity of other types of measures.

In cross-cultural research, a measure needs to have the same structure in each culture in which it is used. In a review of 97 cross-cultural measurement studies conducted over a 13-year period, Chen (2008) found structure differences in 74% of the measures studied, indicating a differential validity problem. These structural differences contributed to differences in the reliability coefficients found for the measures in the different cultures studied. Chen concluded that

when we compare diverse groups on the basis of instruments that do not have the same [structural] properties, we may discover erroneous “group differences” that are in fact artifacts of measurement, or we may miss true group differences that have been masked by these artifacts. As a result, a harmful education program may be regarded as beneficial to the students, or an effective health intervention program may be considered of no use to depressive patients. (p. 1008)

Because of the potential for differential validity, well-conducted programs of validation research will test for it. Because those tests are not always conducted, it is wise to avoid using measures that have not been validated for the groups one plans to use in research.

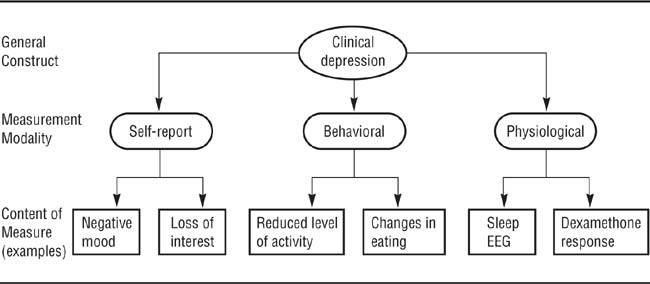

The term modality of measurement refers to the manner in which one measures a person’s characteristics. We will discuss three of the traditional modalities—self-report, behavioral, and physiological—plus the new category of implicit measures.

As the name implies, self-report measures have people report on some aspect of themselves. People can be asked to make several kinds of self-reports. Cognitive self-reports deal with what people think; for example, you might be interested in people’s stereotypes of members of social groups. Affective self-reports deal with how people feel; for example, you might be interested in people’s mood states or in their emotional reaction to a stimulus, such as their liking or disliking for it. Behavioral self-reports deal with how people act, in terms of what they have done in the past (called retrospective reports), what they are currently doing (called concurrent reports), or what they would do if they were in a certain situation (called hypothetical reports). Finally, kinesthetic self-reports deal with people’s perceptions of their bodily states, such as degree of hunger or sexual arousal.

Advantages of self-report measure. Self-reports have two principal advantages relative to the other measurement modalities. First, self-report is often the most direct way to obtain some kinds of information. For example, information about a person’s inner states (such as mood), beliefs (such as those concerning social groups), interpretations (such as whether another person’s behavior is perceived as friendly or unfriendly), and thought processes (such as how a decision was reached) can be obtained most directly through self-report. Behaviors that cannot be directly observed due to privacy concerns (such as sexual behavior) can also be measured by self-report. Second, self-report data can be easy to collect. Questionnaires can be administered to people in groups, whereas other measurement modalities usually require people to participate individually in the research. In addition, the equipment used for measuring self-reports (paper and pencils) is inexpensive compared to the cost of physiological recording equipment and the computer equipment needed for on-line surveys is readily available. Finally, questionnaires can be administered by people who require relatively little training compared to that needed by observers in behavioral research or by the operators of physiological recording equipment.

Limitations of self-report measures. A basic issue concerning self-report measures is people’s ability to make accurate self-reports. Retrospective reports of behavior and events are problematic not only because memory decays over time, but also because memory is reconstructive (Bartlett, 1932; Penrod, Loftus, & Winkler, 1982); that is, events that occur between the time something happens and the time it is recalled affect the accuracy of the memory. For example, the more often people recount an event, the more confident they become of the correctness of their account, even if their beliefs about what happened are actually incorrect. In addition, when people cannot remember exactly what transpired during an event, they report what they believe should have happened under the circumstances—a report that is often inaccurate (Shweder & D’Andrade, 1980). Finally, Nisbett and Wilson (1977) have suggested that people do not actually know the factors that influence their behavior or their cognitive processes and so cannot accurately report on these factors.

A second limitation of self-reports is that people might not be willing to make totally accurate reports. When asked about socially undesirable behaviors or beliefs, for example, people may edit their responses to make themselves look good. Even when the behavior of interest is neutral, people who feel a high degree of evaluation apprehension, either as a personality trait or as a result of the research situation, might alter their responses to make a positive self-presentation (Weber & Cook, 1972).

Finally, self-reports depend on the verbal skills of the respondents. That is, respondents must be able to understand the question, formulate a response, and express the response in the manner required by the researcher (for example, on a 7-point scale). To a large extent, this problem can be addressed by using a vocabulary appropriate to the respondent population. For some categories of people—such as children, the developmentally disabled, people with some forms of mental disorder—there might be a question of their ability to make valid self-reports or to use rating scales. In some cases, however, it might be possible to test respondents’ ability to make an appropriate response and one might therefore have confidence that the report was made properly (Butzin & Anderson, 1973).

Despite these shortcomings, self-report may be the best available measurement modality for a study. When you use self-report measurement, you can take several steps to alleviate its limitations. When asking people about their behaviors, ask about things they have actually done, not about what they would or might do under a set of circumstances: People are poor predictors of how they would behave in situations they have not encountered. Also, ask only about recent behaviors to reduce the influence of memory decay. Phrase the questions you use clearly and precisely; Chapter 15 discusses question wording. Structure the research situation to reduce the influence of factors that might motivate people to edit their responses; Chapter 7 discusses these techniques. Finally, whenever possible, check the validity of self-reports with other kinds of evidence. For example, self-reports of levels of anxiety or nervousness might be checked against observers’ ratings of behaviors associated with these states or against measures of physiological arousal.

In behavioral measurement the researcher watches and records what people actually do, as opposed to self-reports, which focus on what people say they do. Behavioral measures are used in research for any of three reasons. The first reason is because the behavior itself is under study; for example, the effectiveness of the treatment of a child for disruptive behavior might be assessed by having the child’s parents and teachers keep records of his or her behavior. Second, the behavior may be used as an operational definition of a hypothetical construct; for example, level of aggression might be assessed as the frequency with which a research participant delivers a supposed electric shock to a confederate of the experimenter who is posing as another participant. Finally, behaviors may be used as nonverbal cues to psychological states; for example, speech disfluencies, such as stuttering, might be used as indicators of nervousness.

Aronson, Ellsworth, Carlsmith, and Gonzales (1990) also describe what they call behavioroid measures, which they define as “an approximation of a behavioral measure [that] may be achieved by measuring subjects’ commitment to perform a behavior, without actually making them carry it out” (p. 271). For example, people’s helpfulness might be assessed by asking them to sign up to conduct a time-consuming tutoring session. Although this commitment is a type of self-report, Aronson et al. suggest that “the crucial difference between a simple questionnaire item and a behavioroid measure is that the latter has consequences. From the subjects’ point of view, they cannot just check a scale and forget it, they are committing themselves to future behavior” (p. 272).

A technique similar to self-report is experience sampling, in which people use diaries to record behaviors as they are performed or soon thereafter. This technique differs from self-report in that the recording and reporting of the behavior are concurrent with the behavior (or almost so) rather than retrospective. Researchers can control the timing of the behavior samples by using electronic “beepers” to cue participants to record their current behavior (Conner, Barrett, Tugade, & Tennen, 2007).

Many aspects of behavior can be measured. These aspects include the frequency, rate (frequency per unit time), and speed with which a behavior is performed; the latency (time between stimulus and response), duration, and intensity of a behavior; the total amount of different (but perhaps related) behaviors that are performed; the accuracy with which a behavior is performed (for example, number of errors); and persistence at the behavior (continued attempts in the face of failure).

Advantages of behavioral measures. A major advantage of behavioral measures is that they can be used without people’s being aware that they are under observation. As a result, evaluation apprehension, which can lead to edited behavior just as it can lead to edited self-reports, is greatly reduced (Webb, Campbell, Schwartz, & Sechrist, 2000). Covert observation can be conducted not only in natural settings, such as when Baxter (1970) observed sex, ethnic group, and age differences in the use of personal space at a zoo, but also in laboratory research. An example of the latter is Latané and Darley’s (1968) study in which people who thought that they were waiting for an experiment to start were confronted with a simulated emergency; the behavior of interest was whether they reported the emergency. One must, however, be sensitive to the ethical implications of using deception to elicit behavior. Another approach is study artifacts that people create. For example, Krämer and Winter (2008) examined people’s homepages on the German social networking site, StudiVZ, to study self-presentation; the authors coded variables such as the person’s expression in their profile picture, the amount and type of information they chose to reveal, and the number of photos showing the person in groups.

A second advantage of behavioral measures is that some behaviors are performed automatically, without premeditation, thereby bypassing the editing process. These behaviors might therefore be used as nonverbal cues to provide more accurate indications of psychological states than would self-reports. Zhang, Jeong, and Fishbein (2010), for example, assessed people’s ability to multitask by asking them to read while paying close attention to sexually explicit television clips; performance was measured by participants’ ability to later recognize the TV content. Finally, Aronson et al. (1990) suggest that having people perform an action is more psychologically absorbing and interesting to them than is filling out a questionnaire, and is therefore more likely to result in accurate responses. In effect, people’s absorption in the task is expected to lead them to not think about editing of their behavior.

Limitations of behavioral measures. The most basic limitation of behavioral measures is that “what you see is what you get.” That is, although behavioral measures allow you to record what people do, you cannot know their reasons for doing it or what their behavior means to them. If, for example, a social networker posts song lyrics about a failed relationship, you might assume he recently experienced a break-up, but it’s also possible that he simply likes the song. According to the symbolic interactionist point of view, all behavior has meaning to the people involved and this meaning must be known to properly interpret the behavior (Stryker & Statham, 1985). It can therefore be useful to supplement behavioral measures with self-reports. Similarly, although one might wish to assume that nonverbal cues are indicators of psychological states, the validity of any particular cue as an indicator of any particular state (its construct validity) might not be well established. For example, although eye contact can indicate liking (Exline, 1971), does lack of eye contact indicate dislike, or does it indicate shyness? Both convergent and discriminant validity must be established before using a nonverbal cue as an indicator of a psychological state.

Another limitation of behavioral measures is that behaviors can be highly situation- specific; that is, a behavior observed in one situation might not be observed in another, relatively similar situation. Because any one research participant is usually observed in only one situation, the generalizability across situations of the conclusions drawn from behavioral measures may be limited. This specificity of a particular set of behaviors to a particular situation can sometimes be a problem, especially if behaviors are being used as indicators of personality traits, which are assumed to be consistent across situations (Kazdin, 2003). Finally, the use of behavioral measures requires that observers be trained to accurately observe and record the behaviors of interest, and that a system be developed for classifying the observations into meaningful categories. These processes can be expensive in terms of time and money.

Physiological measures are used to assess people’s biological responses to stimuli. Most physiological responses cannot be directly observed, but must be recorded using electronic or mechanical instruments. These responses include neural activity, such as electroencephalograph (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data; autonomic nervous system activity, such as blood pressure, heart rate, respiration, and the electrical conductivity of the skin; and hormone levels, such as the concentration of adrenaline in the blood. Some physiological measures also allow the precise quantification of observable bodily responses that could not otherwise be measured with precision, such as muscular activity, sexual arousal, and pupil dilation (Diamond & Otter-Henderson, 2007). They also allow a continuous measure of process, allowing the researcher, for example, to evaluate what stage of processing is influenced by an experimental manipulation. As Hoyle, Harris, and Judd (2002) put it, “physiological monitoring … can go beyond the relatively simple question of whether a stimulus has an influence to the more refined question of when it exerts an influence relative to the onset of a stimulus or event” (p. 117). Behavior responses, in contrast, assess response at a discrete point in time (Luck, 2005).

Researchers use physiological measures for either of two reasons. First, the biological variable might be of interest in and of itself. For example, variation in blood pressure response to different stimuli is studied as one route to understanding the causes of hypertension (Steptoe, 1981). Second, physiological response is sometimes used as an operational definition of a psychological state. fMRI technology, for example, has been used to assess emotional responses to Black and White faces (Phelps et al., 2000) and to assess anxiety related to public speaking (Lorberbaum et al., 2004).

Advantages of physiological measures. Physiological measures have three principal advantages. First, they provide the most direct means of quantifying biological responses. Second, they can provide highly precise measurement, and the degree of error of measurement is usually well known and so can be easily taken into account when interpreting data. Finally, the variables assessed by physiological measures are usually not under people’s voluntary control and therefore cannot be easily edited, as can self-reports and behaviors. Although people can be trained through biofeedback to control some physiological responses, under most circumstances a researcher is unlikely to encounter someone who has had such training.

Limitations of physiological measures. Physiological measures have a number of limitations, both in general and especially as operational definitions of psychological variables. Physiological measurement depends on sophisticated electronic and mechanical equipment that is usually expensive to purchase and maintain. In addition, operators must be trained in using and maintaining the equipment, which involves time and perhaps money. Physiological measures produce a great deal of information, including undesirable extraneous information, so training is also needed to separate the “signal” or desired information, from the “noise.” Some physiological measuring devices are also very obtrusive and so may interfere with the physiological processes being measured. For example, many people become nervous when electrodes are attached to their bodies and this nervousness will alter their physiological responses. Physiological recording may require research participants to undress at least partially, also increasing some people’s nervousness. Physiological studies can be long and boring and if participants lose interest, it can interfere with the quality of the data. Finally, physiological measuring devices frequently constrain people’s freedom of movement; movement may dislodge sensors attached to the body and also may be a source of irrelevant variance (unreliability) in the measurements. The sensors must also be attached to recording mechanisms, which may not be very portable. However, the last problem is becoming less important as technological advances miniaturize recording instruments.

Although physiological variables have frequently been used as indicators of psychological states, such use is inadvisable because, in most cases, there is no evidence for the construct validity of a particular physiological variable as a measure of a particular psychological state (Blascovich, 2000). To establish construct validity, one must be able to show (a) that a particular psychological state results in a particular physiological response (convergent validity) and (b) that the physiological factor varies only in response to changes in the psychological state (discriminant validity). The first condition has been met for many psychological-physiological relationships, the second for only a few (Blascovich, 2000). As a result, Aronson et al. (1990) recommend that physiological measures be used only as indicators of general somatic arousal, not as indicators of specific psychological states unless there is clear evidence of their construct validity.

Even as indicators of generalized arousal, physiological measures have their limitations. They can be very sensitive to the effects of participant variables irrelevant to arousal, such as bodily movement (including speech) and changes in direction of attention, and to environmental variables, such as changes in room temperature and lighting level (Cacioppo & Tassinary, 1990). Physiological measures should therefore be used only in closely controlled environments in which the influence of factors such as these can be minimized.

Some measures can be classified as explicit measures; these measures assess responses that the research participant can think about and consciously control. Self-reports are examples of explicit measures: Respondents can think about the questions they are asked, decide on what response to make (perhaps editing it to avoid responding in a way that would make them look bad), and then give the response. In contrast, implicit measures assess responses people make without thinking or are involuntary, and so cannot easily be edited (Nosek, 2007). For example, an explicit measure of racial prejudice might directly ask White research participants about their beliefs about and feelings toward African Americans; biased respondents can easily avoid appearing prejudiced by editing their responses. Another way to measure prejudice would be to observe White people interacting with African Americans and observing nonverbal behaviors such as eye contact and posture: behaviors such as avoiding eye contact with and leaning away from another person are indicators of dislike that most people engage in without being aware of doing so (Maas, Castelli, & Acuri, 2000). Implicit measures can take a number of forms (Wittenbrink & Schwarz, 2007), but we will organize our discussion around the Implicit Association Test (IAT), which is one of the most widely-used implicit measures (Lane, Banaji, Nosek, & Greenwald, 2007). If you are unfamiliar with the IAT, it is described in Box 6.2.

Advantages of implicit measures. As described in Box 6.2, the IAT uses a response-competition format that requires research participants to respond as quickly as possible. This format does not give participants time to consciously analyze their responses, and so they do not have time to edit them. As a result, the IAT and other implicit measures are assumed to tap into people’s true beliefs and feelings rather than the possibly edited ones tapped by explicit measures. Implicit measures also provide a possible solution to the problem posed by Nisbett and Wilson (1977) that we described earlier: People may not be able to make to make accurate self-reports because they are unable to accurately assess their own motivations, beliefs and feelings. For example, some theories of prejudice postulate that that some people believe that they are not prejudiced and so respond that way on explicit measures of prejudice; however, they still hold unconscious prejudices that show up in their behavior (Whitley & Kite, 2010). There is now a fairly large body of evidence indicating that the IAT and other implicit measures can tap into such unconscious motives, beliefs, and feelings (see, for example, Lane et al., 2007). Finally, implicit measures can aid in developing operational definitions that allow better tests of theories. For example, to conduct a rigorous test of theories that postulate a distinction between conscious and unconscious prejudice, one must be able to distinguish among people who are high on both types of prejudice, low on both types, and those who are high on one type but low on the other. It was the development of implicit measures that allowed researchers to make those distinctions (for example, Son Hing, Li, & Zanna, 2002).

The Implicit Association Test (IAT) was originally developed to study prejudice but has since been applied to a wide variety of research areas including political psychology, clinical psychology, health psychology, personality, and marketing (Lane. Banaji, Nosek, & Greenwald, 2007). The IAT is based on the concept of response competition, which pits two responses against each other, a habitual response and an opposing response. The stronger the habitual response, the longer it takes to make an opposing response. The opposing response is slower because, instead of just making the response without thinking about it (as is the case with a habitual response), the person has to inhibit the habitual response and replace it with an opposing response. An IAT score represents the difference in time required to make habitual and opposing responses: longer opposing response times relative to habitual response times indicate stronger habitual associations.

For example, people who like coffee but dislike tea will generally associate positive concepts such as pleasant with coffee and negative concepts such as unpleasant with tea. In an IAT assessment of preference for coffee versus tea, someone who likes coffee would be shown a series of words or pictures on a computer screen and instructed to press one key if a word is either positive (such as pleasant) or associated with coffee (such as Folger) and to press another key if a word is either negative (such as unpleasant) or associated tea (such as Lipton). This task will be relatively easy for a coffee- lover because it requires a habitual response: associate a positive concept with coffee. However, it would be relatively difficult for coffee-lovers to respond correctly if they are instructed to press one key if a word is either negative or associated with coffee or to press a different key if the word is either positive or associated with tea. This difficulty arises because the coffee lover’s first impulse when shown a word associated with tea is to press the negative key, but that is the wrong response in this case because negative is represented by the same key as coffee. To make a correct response, coffee- lovers would have to inhibit their initial response (the coffee/positive or tea/negative key) and replace it with the opposing response (the tea/positive key). Lane et al. (2007) provide a detailed description of the IAT procedure and the experimental controls that must be used with it.