The Concept of External Validity

Components of External Validity

The Structural Components of External Validity

Person-by-situation interactions

Levels of the independent variable

The Functional and Conceptual Components of External Validity

Relationships Among the Components of External Validity

The components of ecological validity

Laboratory Research, Natural Setting Research, and External Validity

Laboratory Research and Ecological Validity

Ecological validity as an empirical question

Natural settings and generalizability

Structural versus functional and conceptual verisimilitude

Philosophies of science and naturalism in research

External Validity and Internal Validity

Suggestions for Further Reading

Questions for Review and Discussion

Every research study is unique: It is carried out in a particular setting, using particular procedures, with a particular sample of participants, at a particular time. At the same time, studies are often conducted to determine general principles of behavior that are expected to operate in a variety of circumstances. An important question, therefore, is the extent to which the findings from any one study apply in other settings, at other times, with different participants, when different procedures are used.

This question represents the issue of external validity. In this chapter, we first consider the concept of external validity and define its components. We then consider each of the components of external validity in more detail. After that we discuss ways of assessing the external validity of research. We conclude the chapter by examining the continuing controversy over the applicability of the results of laboratory research to natural settings and by considering the relationship between internal validity and external validity.

The concept of external validity can be expressed as a question: Are the findings of a study specific to the conditions under which the study was conducted, or do they represent general principles of behavior that apply under a wide-ranging set of conditions? Because of this focus on how broadly findings apply, the term generalizability is often used synonymously with external validity; however, we will use the term generalizability to refer to a specific aspect of external validity. In this section we examine the two most common ways in which the term external validity is used and identify and define the components of external validity.

Cook and Campbell (1979) identify two aspects of external validity. One aspect they call “generalizing across,” which refers to the question of whether the results of a study pertain equally to more than one setting, population, or subpopulation, such as to both men and women. The other aspect they call “generalizing to,” which refers to the question of whether the results of a study pertain to a particular setting or population, such as hospitalized psychiatric patients.

To a large extent, basic researchers are more interested in the “generalizing across” aspect of generalizability than in the “generalizing to” aspect. This focus derives from their interest in discovering general principles of behavior and theories that will apply regardless of population, setting, or operational definition. If a principle does not operate as expected under a particular set of circumstances, those circumstances are incorporated into the theory as boundary, or limiting, conditions (see Chapter 5).

Somewhat in contrast to the basic researchers’ focus on “generalizing across,” applied researchers are more interested in the “generalizing to” aspect of generalizability. This focus derives from their interest in using theory and research to solve problems in particular settings (such as psychology clinics, the criminal justice system, and schools) that are inhabited by particular populations (such as therapists and patients; police officers, defendants, attorneys, judges, and jurors; and teachers, students, parents, and administrators). Consequently, applied researchers place a high value on what Brunswik (1956) called the ecological validity of research. The term ecological validity refers to the degree to which the conditions under which research is carried out mimic the conditions found in a natural setting to which they are to be applied. The strictest interpretation of the concept of ecological validity holds that only the results of research conducted in the setting itself are valid for application to that setting.

This discussion will distinguish between the generalizing-across and the generalizing-to aspects of external validity by referring to the generalizing-across aspect as gener-alizability and the generalizing-to aspect as ecological validity. However, as Cook and Campbell (1979) note, these aspects are closely related, so be careful not to overemphasize the difference between them. After all, if a principle generalizes across variations in a set of conditions, such as participant populations, then it generalizes to each of those conditions. For example, if a principle generalizes across sex of research participant, it is applicable to both women and men.

The differing views of external validity on the part of basic and applied researchers have led to a somewhat acrimonious debate over the applicability of laboratory-based theories and research findings to natural settings. Some of the issues in this debate are considered in the last section of this chapter. The aspect of the debate discussed in this section is the nature of the concept of external validity, especially in its sense of ecological validity. Vidmar (1979) has suggested that external validity has three components: a structural component that is relevant to both generalizability and ecological validity, and functional and conceptual components that are more relevant to ecological validity. These relationships are illustrated in Figure 8.1.

The structural component. The structural component of external validity is concerned with the method by which a study is carried out, including factors such as the setting in which the study is conducted, the research procedures used, and the nature of the participant sample. The findings of a particular study are high on the generalizability aspect of external validity to the extent that they remain consistent when tested in new studies that use different methods. That is, studies that test the same hypothesis should get reasonably similar results regardless of differences in settings (such as laboratory or field), research procedures (such as operational definitions), and research participants (such as college students or factory workers). Conceptual replication of research (discussed in Chapter 5) is therefore one way of testing the generalizability of research. Research findings are high on the ecological validity aspect of external validity to the extent that they can be replicated in a particular natural setting, using the procedures normally used in that setting and with the people usually found in the setting.

The Meanings of External Validity.

External validity has two components: generalizability, which deals with questions of whether the results of a particular study can be replicated under different conditions, and ecological validity, which deals with the question of whether a finding can be applied in a particular setting. Generalizability therefore focuses on whether different aspects of the structure of research (such as settings, procedures, and participant populations) lead to differences in findings, whereas ecological validity focuses on the similarity between a study and a natural setting to which its results will be applied. This similarity includes similarity in the structure of the research and natural settings, similarity in the psychological processes operating in the settings, and similarity in the issues studied in the research setting and those of importance in the natural setting.

Consider, for example, a laboratory study on the effects of college student participants’ having a say in setting task goals on the satisfaction they derive from performing the task, with satisfaction assessed by a paper-and-pencil measure. The generalizability of the results of the study could be tested by having students at another college participate or not participate in setting goals for a different task and assessing their satisfaction using a different paper-and-pencil measure. The ecological validity of the results could be tested by seeing if they apply in a particular factory with the people who work there, using a naturalistic indicator of satisfaction such as the number of grievances filed by the workers. Notice that a test of the ecological validity of a research finding is essentially a conceptual replication of that finding and is therefore also a test of the finding’s generalizability. The second section of this chapter examines some factors that can affect the structural component of external validity.

The functional component. The functional component of external validity is the degree to which the psychological processes that operate in a study are similar to the psychological processes at work in a particular natural setting. Because of its focus on the degree to which a component of research mimics a component of a natural setting, the functional component of external validity pertains primarily to questions about the ecological validity of research results. For example, the question of whether people who participate in mock jury research, whose decisions have no effect on anyone’s life, process evidence and make decisions in the same way as real jurors, whose decisions have important effects on people’s lives, is a question of the functional validity of mock jury research. The third section of this chapter discusses the functional component of external validity.

The conceptual component. The conceptual component of external validity is the degree to which the problems studied in research correspond to problems considered important in a natural setting. Like questions concerning the functional component of external validity, those concerning the conceptual component of external validity arise primarily in the context of ecological validity. For example, researchers who study crowding are often interested in its psychological effects, such as stress. However, people in natural settings who must deal with crowded conditions, such as prison administrators, are more interested in its behavioral effects, such as aggression (Ruback & Innes, 1988). Therefore, from the viewpoint of prison administrators, research on the psychological effects of crowding is low on conceptual validity. The third section of this chapter discusses the conceptual component of external validity along with the functional component.

Let’s recapitulate the discussion so far. As Figure 8.1 shows, external validity has two aspects: generalizability, or the extent to which research results hold up across variations in the structure of studies, and ecological validity, or the extent to which research results can be applied to a particular natural setting. Table 8.1 summarizes the three components of external validity.

Issues of structural validity apply to questions of both generalizability and ecological validity, whereas issues of functional and conceptual validity apply primarily to questions of ecological validity. Vidmar (1979) used the term verisimilitude to refer to the similarity between research settings and natural settings and thus to the ecological validity of research. We will also use the terms structural, functional, and conceptual verisimilitude when discussing ecological validity.

Epstein (1980) suggests that researchers want to generalize their findings across four structural dimensions: settings, participant samples, research procedures, and time; cultures can also be included in this list (see also Agnew & Pyke, 2007). The setting concerns the physical and social environment in which the research takes place. Participants are the people from whom data are collected and who can represent different subgroups or classes of people, such as sex or race. Research procedures include operational definitions, instructions, and tasks. Time represents the possibility that relationships between variables may not be stable, but may change as a function of historical events or social change. Culture concerns the shared history, traditions, and worldview of a social group. To the extent that research findings represent general principles of behavior, they should be relatively stable across each of these dimensions. The following sections discuss some of these factors that can affect the external validity of research.

The Structural. Functional, and Conceptual Components of External Validity

Component |

Focus |

Issue Addressed |

Structural |

Methodology |

Are the results of research consistent across variations in settings, procedures, populations, etc.? |

Functional |

Psychological Processes |

Are the psychological processes that operate in research settings similar to those operating in applicable natural settings? |

Conceptual |

Research Question |

Is the research question under investigation one of importance in the applicable natural setting? |

Parenthetically, note that although these factors are sometimes called “threats to external validity,” it is more accurate to consider them sources of study-to-study extraneous variation in tests of the same hypothesis. The better a hypothesis holds up across these variations, the more likely it is to be generally applicable; failures to hold up suggest limits on its applicability.

Research settings vary considerably from study to study. Not only can the physical setting (and its potential for reactivity) vary, but even within settings such factors as characteristics of the researcher and of the other people taking part in the research with the participant can vary from study to study. This section discusses the effects of these setting factors on generalizability and ecological validity.

The physical setting. Aspects of the physical setting can affect research participants’ responses to the independent variable and thereby affect the generalizability of the results of research conducted in the setting. Rosenthal (1976), for example, found that research participants’ evaluations of an experimenter varied as a function of the room in which they made their evaluations. Behavior can be altered by as seemingly minor a factor as the presence or absence of a mirror in the laboratory room (Wicklund, 1975); people become more concerned with making a good impression when they see a reflection of themselves. Cherulnik (1983) notes that this finding can have important implications for researchers who use “one-way” mirrors to observe people’s behavior: The participants’ behavior may change even if the participants don’t realize that they are under observation. Physiological measures, such as blood pressure, can also be affected by the physical setting (Biner, 1991). To the extent that aspects of research environments interact with the independent variable, responses can vary from setting to setting. It is therefore important to examine the research environment for any factors that might interact with the independent variable to affect the dependent variable.

Environments can also have long-term effects that limit the generalizability of research. For example, even small changes to an animal’s environment can produce neuronal changes; animals living in a stimulating environment, for example, develop a thicker cortex and have an increased number of neurons and synapses. These changes can affect many aspects of an animal’s behavior, including memory and learning and response to stress, leading some researchers to question whether research conducted with animals living in standard laboratory condition generalizes to animals living in enriched settings (see Cohen, 2003).

Reactivity. As noted in Chapter 7, the term reactivity refers to people’s tendency to change their behavior when they know they are under observation. To the extent that research settings are differentially reactive, responses to the same independent variable may differ between those settings. Researchers have developed a number of techniques for reducing the reactivity of the research setting, such as naturalistic observation, field experiments, and various forms of deception. Even when participants are fully aware of being in an experiment, reactivity can often be reduced by creating a high degree of experimental realism: manipulating the independent variable in such an engaging manner that subjects become so psychologically involved in the situation that they give realistic responses (see Chapter 16). Some research, such as laboratory studies of sexual arousal, is inherently likely to produce reactivity. Experimenters can reduce participants’ anxiety in these settings by providing detailed information about procedures, explaining how privacy is maintained, and demonstrating the equipment that will be used prior to the beginning of the study (Rowland, 1999).

Researcher attributes. It should come as no surprise that people’s behavior is affected by the characteristics of the persons with whom they interact. In a research study, the participant interacts with the experimenter, and the experimenter’s characteristics can affect the participant’s responses. For example, variation in sex of experimenter has been associated with variation in the accuracy of task performance, the reporting of intimate information, and response to projective tests, among other variables (Rumenik, Capasso, &Hendrick, 1977). The ethnicity of the experimenter can affect task performance (Marx & Goff, 2005), physiological response (Bernstein, 1965), and self-reports of the unpleasantness of a pain tolerance task (Weisse, Foster, & Fisher, 2005). In addition to gender and ethnicity, other experimenter characteristics, such as personality, values, and experience, can affect participants’ behavior (Rosnow & Rosenthal, 1997). However, Barber (1976) points out that the effects of these nonphysical experimenter attributes may be relatively small. Researchers can assess the impact of experimenter attributes by using multiple experimenters and including the experimenter as a factor in the data analysis. Another way to eliminate experimenter effects is through the use of computer-assisted interviewing techniques, which allow the respondent to respond privately by typing responses into a computer instead of reporting their answers directly to an interviewer. These procedures also increase participants’ willingness to accurately report about their sexual behavior, illicit drug use, or engagement in other sensitive behaviors (Gribble, Miller, Rogers, & Turner, 1999).

Coparticipant attributes. When people participate in an experiment in groups, the potential exists for them to be influenced by each other’s behavior and personal characteristics. Even when they don’t speak to each other, coparticipants’ physical characteristics, such as ethnicity and gender, might have an influence on behavior. McGuire (1984) has shown, for example, that when someone is the sole member of his or her gender or race in a group, that characteristic becomes more salient to the person. This phenomenon has been found to affect responses to personality inventories (Cota & Dion, 1986) and could have other effects as well. In addition, Mendes, Blascovich, Lickel, and Hunter (2002) found that that White research participants showed cardiovascular responses associated with threat when interacting with a Black man, but not when interacting with a White man. However, on self-report measures in this same experimental situation, White participants reported liking the Black man more than the White man. More generally, research shows that White people exhibit nonverbal signs of anxiety and discomfort when interacting with Black people (Dovidio, Kawakami, & Gaertner, 2002). Experimenters should consider whether these types of reactions could produce responses in their research participants that could adversely affect the data being collected. Solutions to this problem include making participant groups as homogeneous as possible and having people participate individually rather than in groups.

Ecological validity. In terms of ecological validity, the physical, social, and psychological structure of a research setting, especially a laboratory setting, can be very different from that of a natural setting, such as the workplace or the clinic. Consequently, behavior in the usually less complex laboratory setting may be very different from that in the natural setting (Bourchard, 1976). This difference may be especially important in settings that may be designed to influence the processes that take place there, such as the psychology clinic (Kazdin, 2008). In the social structure of the laboratory, the research participant is usually cut off from his or her natural social network, and is often placed in the position of being a passive recipient of the researcher’s manipulations rather than being proactive and interactive with other people (Argyris, 1980). The most ecologically valid research setting from the structural point of view, therefore, is the natural setting of the behavior or process of interest. Lacking access to the natural setting, the research setting should be as similar to it as possible, that is, be characterized by what Aronson, Ellsworth, Carlsmith, and Gonzales (1990) call mundane realism (see Chapter 16). For example, jury research might take place in the mock courtroom of a law school.

Although research settings show a high degree of variability in their characteristics, research participants are often quite homogeneous in their demographic, social, and psychological characteristics, which can be very different from those of the population in general. This section considers some of the effects of that homogeneity on the generalizability and ecological validity of research results.

Convenience sampling. As we will discuss in Chapter 16, much behavioral science research uses convenience samples of participants; that is, participants are chosen on the basis of availability rather than on the basis of representativeness of the population as a whole or of a particular subpopulation. The most convenient participants for most researchers are college students, which has led to the assumption that the results of such research are ungeneralizable to other populations (Sears, 1986). Because this question is closely related to that of ecological validity, it will be addressed as part of that discussion at the conclusion of this section.

Restricted sampling. Sometimes participant samples are restricted to one category of persons, such as men, young adults, or White respondents. For example, racial minorities have been so rarely included in behavioral science research that Guthrie (1998) titled his history of African Americans in psychology Even the Rat was White. Moreover, Graham (1992) reports that studies published in prestigious journals are currently less likely to include African Americans than studies published 25 years ago. The age of participants is also frequently restricted. Sears (1986) found that only 17% of adult subjects in social psychological research were older than the average college student. Men have appeared as research participants much more often than have women, although this situation has improved in recent years (Gannon, Luchetta, Rhodes, Pardie, & Segrist, 1992).

Participant samples also are restricted in that psychological research relies primarily on respondents from the United States and Western Europe. Arnett (2008) analyzed the international representation of research participants, based on a study of six top journals chosen to represent diverse subfields of psychology. Although Americans make up only 5% of the world’s population, Arnett found that 68% of the participants in the studies he reviewed were American and, within this subset of studies, 77% of the respondents were majority European American descent. Thirteen percent of the studies used European participants; other world areas were vastly underrepresented (3% Asian, 1% Latin American samples, 1% Israeli, and less than 1% African or Middle Eastern). Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan (2010) note that this reliance on samples of American college students is WEIRD—that is, these participants are disproportionately likely to be Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic—and so are not representative of the diversity of the world’s populations. Thus, it may be difficult to generalize much of behavioral science research across populations because of the predominance of American or European American college students as research participants.

Ecological validity. The question of the representativeness of a research sample is closely related to the topic of ecological validity or to whether the results apply to other settings. Behavioral science research has been criticized for its reliance on research participants who are unrepresentative of the populations to which the results of research might be applied. As noted above, psychologists rely heavily on college student participants in the 18 to 22 age range, and most of this research is based on American samples; this pattern appears to hold true for other areas of behavioral science as well (Endler & Parker, 1991; Henrich et al., 2010). Even within American culture, late adolescents differ from the population in general and from specific populations of interest to many applied researchers, such as factory workers, managers, and psychiatric patients (Sears, 1986). College students are not even representative of late adolescents in general. To the extent that the participants in research differ from the population to which the results of the research might apply, the research is low on structural verisimilitude. Because only a relatively small amount of research is intended to apply solely to college students, their use as research participants is often taken as an a priori indicator of low ecological validity.

Although the most ecologically representative participant sample consists of people from the natural setting of interest, these people are not always available for research. However, for some research, an alternative strategy may be to carefully select college students for similarity to the people in the natural setting of interest. Gordon, Slade, and Schmitt (1986), for example, suggest employing research participants with demographic, personality, and interest profiles as similar as possible to those of members of the natural setting population. Thus, psychopathology research could select college student participants on the basis of appropriate clinical criteria (Sanislow, Perkins, & Balogh, 1989). Gordon et al. also suggest using “nontraditional” students who have the appropriate work experience or background for industrial and organizational research. Because one factor that leads to differences in response by college student and natural setting research participants is experience with naturalistic tasks, Gordon, Schmitt, and Schneider (1984) recommend training naive participants on the task; such training can greatly reduce differences in response. Finally, because college student and natural setting participants might interpret the experimental task differently, thus leading to different responses, Adair (1984) suggests debriefing participants on the perceptions, meanings, and understandings they impute to the research situation, and comparing these factors with those of people from the natural setting.

Volunteer participants. As noted in Chapter 7, people who volunteer to participate in research differ from nonvolunteers in many ways, such as need for approval, sociability, level of education, tendency to seek arousal, intelligence, and conventionality (Rosnow & Rosenthal, 1997). To the extent that these factors interact with the independent variable, there will be a lack of generalizability to nonvolunteers. Even when people are required to participate in research, as are many introductory psychology students, elements of volunteerism remain. People are generally allowed to choose which of several experiments to participate in, and certain types of people are attracted to certain types of studies. For example, men are more likely to volunteer for studies on “masculine” topics such as power and competition, and women for “feminine” topics such as revealing feelings and moods (Signorella & Vegega, 1984). People who volunteer for sex research are more sexually experienced and have more liberal sexual attitudes than nonvolunteers (Farkas, Sine, & Evans, 1978). Because participants can withdraw from research after they learn about the procedures to be used, they can “devolunteer”; Wolchik, Braver, and Jensen (1985), for example, found that volunteer rates for sex research dropped from 67% to 30% for men and from 38% to 13% for women when the procedures required some undressing. These problems point out the importance of reporting participant refusal and dropout rates and of taking the characteristics of “survivors” into account when interpreting results: The results of the research may apply only to people with these characteristics.

Person-by-situation interactions. The possibility that the characteristics of volunteer participants might interact with the independent variable to affect the results of a study is an example of the broader case of the person-by-situation interaction: Different types of people, such as those with different personality characteristics or of different ages, might respond differently to the same independent variable (Cronbach, 1975). Thus, the results of a study might apply only to one type of person if only that type is represented in the study. For example, researchers examining event-related potentials (ERP) typically use small, homogeneous samples. Because hand preference is related to asymmetries in brain and behavior, ERP researchers control for its effects, typically by including only righthanded people, who are the majority in the population, in their research. Doing so, however, means the results of a particular experimental manipulation might not generalize to left-handed people (Picton et al., 2000). Additional research can uncover when person-by-situation interactions influence results. For example, Aronson, Willerman, and Floyd (1966) found that a person’s making a mistake led to lower evaluation of the person when the person was of low status. However, later research revealed that this effect was found only for research participants of average self-esteem; high and low self-esteem participants did not give lower evaluations to a low-status person (Helmreich, Aronson, & LeFan, 1970). It can be useful, therefore, for researchers to carefully examine any project they propose to carry out to determine if the personal characteristics of participants might interact with the independent variables to affect the outcome.

The procedures used in research can affect its external validity in several ways. Specifically, the ecological validity of results can be limited by the use of artificial procedures, incomplete sampling from the possible operational definitions, and a restricted range of values of a construct.

Artificiality. The contention that the setting, tasks, and procedures of laboratory experiments are artificial, and therefore do not generalize to “real-world” phenomena (e.g., Argyris, 1980), is an important aspect of ecological validity and will be discussed in that context at the end of this section. In brief, however, note that laboratory research tends to isolate people from their accustomed environments, to present them with relatively simple and time-limited tasks, and to allow them only limited response modes, such as 7-point scales. Most forms of research, including nonlaboratory methods, are in some degree artificial and can vary in artificiality within a method. These variations can affect generalizability across studies.

Operational definitions. Because any construct can have more than one operational definition, any one operational definition can be considered a sample drawn from a population of possible operational definitions (Wells & Windschitl, 1999). Just as response to a stimulus can vary from person to person, so too can one person’s response vary from operational definition to operational definition. Although these effects are probably most often subtle, they can sometimes be large. For example, whether sex differences in romantic jealousy emerge depends in part on the item wording used on research questionnaires; results can differ depending on whether forced choice or continuous measures are used (DeSteno, Bartlett, Braverman, & Salovey, 2002). The solution to this problem is relatively simple when dealing with dependent variables in an experiment: Use multiple operational definitions of the construct and test commonality of effect through a multivariate analysis (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). As we will discuss in the next chapter, multiple operational definitions of the independent variable are also possible through the use of multiple exemplars of a category, such as by using two men and two women to represent the categories male and female, in a nested design. This procedure is methodologically and statistically complex, but it improves the generalizability of the results. Multiple operational definitions can also be used in correlational research, using latent variable analysis (see Chapter 11).

Levels of the independent variable. Just as it is important to sample from the population of operational definitions, it is important to cover the entire range of the independent variables. As we will discuss in Chapter 9, an experiment using only two levels of a quantitative independent variable assumes a linear relationship between the independent and dependent variables; however, this linear relationship may or may not reflect the true state of nature. For example, DeJong, Morris, and Hastorf (1976) conducted an experiment in which people read a summary of an armed robbery trial; the defendant was one of two men who took part in the crime. In one version of the summary, the defendant had a high degree of responsibility for planning and executing the crime; in another version, he had a lesser degree of responsibility. At the trial, the defendant pleaded guilty to the charge of robbery. Research participants assigned a prison sentence, with a maximum of 10 years, to the defendant. People who had read the summary in which the defendant had a greater responsibility for the crime assigned longer sentences than people who had read the less-responsibility summary. However, Feldman and Rosen (1978) tried to replicate this study and found no relationship between these variables, perhaps because the researchers used different operational definitions of low responsibility (see Whitley, 1982). Specifically, high level of responsibility was defined similarly in both studies; the defendant was described as having about 85% of the responsibility for the crime. In the low level condition, however, DeJong et al. defined low level of responsibility as having 15% responsibility for the crime, whereas Feldman and Rosen defined low level responsibility as having about 50% responsibility for the crime. Feldman and Rosen’s failure to find a relationship between responsibility and punishment could be interpreted as challenging the external validity of DeJong et al.’s results. That is, DeJong et al.’s findings did not appear to apply outside their research context. Whitley (1982) conducted an additional replication of this study that included all three levels or responsibility (15%, 50%, and 85%). Participants assigned low levels of punishment when responsibility was low, but higher and equal punishment at the two higher levels of responsibility. Hence, both DeJong et al.’s and Feldman and Rosen’s studies lacked external validity because neither accurately captured the true responsibility-punishment relationship. Other phenomena may require even more levels of the independent variable to provide an accurate picture of their relationships with dependent variables. For example, the relationship between time spent in the dark and visual adaptation to darkness requires at least five “levels” of time to be properly described (Matlin, 1988). Although using the extremes of an independent variable is often desirable in order to achieve a strong manipulation, it is also wise to include intermediate levels to test for nonlinear effects.

Ecological validity. Sears (1986) suggests that dependence on college students as research participants has led researchers to use artificial, academic tasks that differ considerably from those that most people perform in natural settings. One example of these tasks is the use of experimental simulations, such as the Prisoner’s Dilemma game used in research on conflict and conflict resolution (Schlenker & Bonoma, 1978). Unlike in natural situations, participants in laboratory research complete short-term tasks and they generally suffer no consequences for poor performance or for harm done to others (Fromkin & Streufert, 1976). When participants interact with people other than the experimenter, these people are usually strangers—confederates of the experimenter or ad hoc groups of other research participants—rather than members of natural acquaintance networks.

The demands of experimental control may require artificial means of communication between subjects, such as intercoms (Darley & Latané, 1968). Such artificial conditions could elicit artificial responses from research participants, thereby limiting the application of the results of the research to natural settings. Experimenters also create situations that would never happen in everyday life. For example, in a study of inattentional blindness, participants watched a video of people playing basketball and counted how many passes certain people in the game made. However, the experimenters were interested in how many people noticed that a person in a gorilla costume walked through the basketball game and stayed for 5 seconds (Simons & Chabris, 1999). The percentage of people who noticed the event (54%) may well have been reduced because the unexpected event was also unrelated to people’s real life experience.

Another aspect of procedural artificiality is that dependent measures are often assessed in ways that are highly artificial and that restrict participants’ behavior. For example, rarely in a natural setting do people express aggression by pushing a button on a machine that (supposedly) generates an electric shock, or express their attitudes on 7-point scales—common occurrences in laboratory research on these topics. In addition to being behaviorally restrictive, these methods force participants to respond in terms of the researcher’s theoretical or empirical model rather than in their own terms. For example, to study the kinds of inferences people draw when they read, cognitive psychologists use a talk-aloud procedure that requires participants to read a text one sentence at a time and to stop at set intervals and say what they are thinking (Suh & Trabasso, 1993). Readers in natural environments rarely do either. Finally, the construct being assessed may not resemble the appropriate natural construct. For example, Sperling (1960) tested sensory memory capacity by recording recall of letters flashed on a computer screen. There are two reasons this procedure may have produced higher recall of sensory input than would occur in natural settings. One is that people are more familiar with letters, the stimuli in this study, than with many of the objects that they encounter in their visual world. Another is that sensory memory is thought to constantly receive input from all of the senses and people typically process multiple messages at once. In Sperling’s experiment, however, people focused on just one message.

Also related to the procedural verisimilitude of research is the manner in which research participants are classified on the basis of personal characteristics, such as personality. For example, to determine whether psychotherapy is effective, researchers often look for changes to responses on rating scales, using measures such as the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1972). Changes on these measures, however, do not necessarily translate into changes in clients’ everyday functioning, making it difficult to know whether therapy has been effective (Kazdin, 2008). To the extent that natural setting and research procedures lead to different classifications, structural verisimilitude is lost.

Human behavior is a function not only of the psychological factors and immediate situations normally studied by psychologists, but also of the person’s cultural environment. Matsumoto and Juang (2013) define culture as “a unique meaning and information system, shared by a group and transmitted across generations, that allows the group to meet basic needs of survival, pursue happiness and well-being, and derive meaning from life” (p. 15). Masumoto (2000) also explains what culture is not—it is not race, nationality, or citizenship because, within these groups, individuals may not share the same values and beliefs. Within the United States, for example, there are regional differences in personality and social attitudes (Rentfrow, 2010).

Research shows that responses to similar stimuli can vary greatly from culture to culture. For example, individuals living in Western cultures are more susceptible to the Müller-Lyer illusion, or the perception that lines of the same length look different because of the shape of their endpoints, than are individuals from non-Western cultures—perhaps because “carpentered corners” (rectangular shaped buildings) are more prevalent in Western society (Segall, Campbell, & Herskovits, 1966). Cultures also differ in their value system; people from individualistic cultures, such as Canada, the United States, and Western Europe, focus primarily on the self and personal needs and goals, whereas individuals from collectivist cultures, such as in Asia and South America, focus on the needs of the group. These cultural differences affect behavior in a number of ways. For example, Earley (1993) demonstrated that participants from individualistic cultures were more likely to engage in social loafing, or putting forth less effort in a group than when alone, than were individuals from collectivist cultures. Research also shows that, in general, respondents from individualistic cultures are more likely to engage in a self-serving bias, attributing their success to internal causes and their failure to external factors, than are individuals from collectivist cultures (e.g., Heine, Lehman, Markus, & Kitayama, 1999). However, this cultural difference is reduced when responses are anonymous (Kudo & Numazaki, 2003). Moreover, a study of Japanese participants showed that although they, themselves, did not engage in a self-serving bias, they expected their parents and friends to do so on their behalf (Muramoto, 2003). Such findings demonstrate the complexity of understanding cross-cultural research patterns and highlight the need to be sensitive to the possibility of cross-cultural differences when interpreting and applying the research results.

Time can affect the external validity of research results in two ways: through problems in time sampling in research design and through changes in relationships between variables over time.

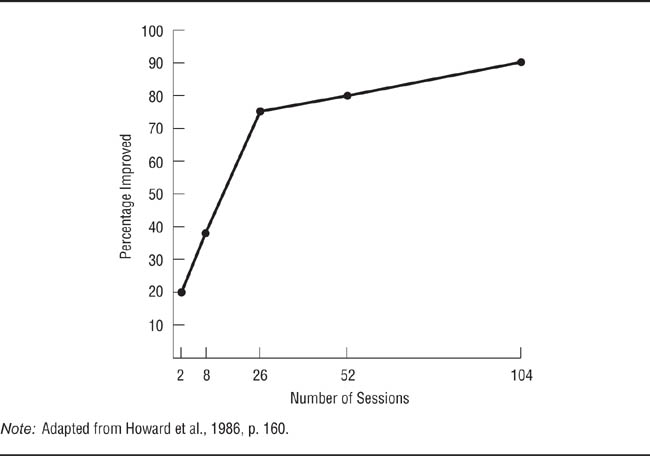

Time sampling. Willson (1981) notes that time can be an important factor in the design of research. Some behaviors are cyclic, their frequency rising and falling at regular intervals. For example, Willson points out that automobile accidents occur more frequently during the winter months in northern states because of adverse weather conditions. Any research aimed at preventing accidents must therefore take seasonal variations in driving conditions into account: The effectiveness of preventive measures instituted during summer might not generalize to winter. Research design must also take into account the amount of time required for an independent variable to have an effect. For example, Figure 8.2 shows the relationship between the number of psychotherapy sessions and the cumulative percentage of patients who improve (Howard, Kopta, Krause, & Orlinski, 1986). This relationship suggests that the results of psychotherapy research would not generalize across studies that used between 2 and 26 sessions: Because the outcome of therapy differs substantially among studies based on 2, 8, and 26 psychotherapy sessions, conclusions drawn on the basis of a 2-session study might not apply to psychotherapy that lasted 8 sessions; similarly, the results of an 8-session study might not apply to psychotherapy that lasted 26 sessions. However, the percentage of patients who improve changes little from 26 to 104 sessions, suggesting that you could make generalizations about the effectiveness of therapy that lasted at least 26 sessions.

Relation of Number of Sessions of Psychotherapy and Percentage of Patients Who Improved.

The results of studies based on therapy lasting from 2 to 26 sessions do not generalize to therapy lasting more than 26 sessions.

Changes over time. Beliefs and behaviors change over time; three commonly cited examples are criteria for physical attractiveness (Etcoff, 1999), sexual mores (Allyn, 2000), and gender roles (Twenge, 1997). Such changes led Gergen (1973) to classify the study of the sociocultural aspects of behavior as the study of history, holding that cultural change makes it impossible to identify immutable laws of social behavior. Although this view has not been generally accepted (see Blank, 1988, for a history of the debate), researchers should be sensitive to the possibility of the obsolescence of research findings and should conduct replication studies for findings that may be vulnerable to change (for example, see Simpson, Campbell, & Berscheid, 1986).

Although Vidmar first distinguished between the structural, functional, and conceptual components of external validity in 1979, most discussions of external validity have focused on its structural component, especially in relation to ecological validity. Nonetheless, the other components have important implications for external and ecological validity; let’s briefly examine some of them.

As noted earlier, the functional component of external validity, or functional verisimilitude, deals with the question of the extent to which the psychological processes that affect behavior in the research situation are similar to those that affect behavior in the natural situation. Jung (1981) cites experimental research on the effects of television violence on aggressive behavior as an example of research that is relatively low on functional verisimilitude. Although the experiments are high on structural verisimilitude because they use real television programs, the experimental requirement of random assignment of participants to conditions lessens their functional verisimilitude. Random assignment is designed to balance individual differences across groups; however, if individual differences determine who does and does not watch violent television programming in natural situations, the experiment no longer accurately models the natural process, and functional verisimilitude is lost. One such factor related to watching violent television programs is trait aggressiveness: Children who have a history of aggressiveness prefer violent television programs to nonviolent programs (Milavsky, Stipp, Kessler, & Rubens, 1982). As important as functional verisimilitude is, it can sometimes be difficult to assess. For example, legal restrictions limit researchers’ access to real juries so that functional comparisons cannot be made between the processes that affect real jury decisions and the processes observed in simulated juries (Bermant, McGuire, McKinley, & Salo, 1974).

As noted, the conceptual component of external validity, or conceptual verisimilitude, deals with the question of the degree to which the problems studied in research on a topic correspond to problems found in the natural situation. Kazdin (1997), for example, questions the conceptual verisimilitude of laboratory studies of systematic desensitization of phobias because such studies usually deal only with mild fears of small animals, whereas clinical phobias are much more severe and center around a greater variety of stimuli. Similarly, the “subclinical” depression usually studied in college students may be conceptually quite different from the forms of depression found in clinical populations (Depue & Monroe, 1978).

Conceptual verisimilitude can be especially important for researchers who want their work to be applied to “real-world” problems—if the researcher’s conceptual system does not match that of the policy makers who are expected to implement the research in the applied setting, the results of the research will not be used. As you will recall from Chapter 5, Ruback and Innes (1988) suggest two ways in which researchers’ and policy makers’ conceptions of research differ. The first difference is that policy makers need research involving independent variables over which they have control and so can change. As Ruback and Innes note, these variables, which they call policy variables, may or may not be the most important determinants of behavior in a situation; however, they point out, if a variable cannot be changed, knowledge about its effects cannot lead to policy changes. Researchers, however, more often focus on variables that can be manipulated in the laboratory, which Ruback and Innes call estimator variables; however, these variables are not useful to policy makers because there is no way policy makers can control them. For example, in terms of factors affecting the accuracy of eyewitness testimony, the degree of anxiety experienced by a witness during a crime is an estimator variable because the criminal justice system cannot control it; however, the time between the witnessing of the crime and the giving of testimony can be controlled, and so is a policy variable.

The second difference is in what Ruback and Innes (1988) refer to as the utility of the dependent variables used—the degree to which the behavior studied is of direct interest to the policy maker. For example, prison authorities are more interested in prisoner violence, illness, and mortality than they are in prisoners’ perceptions of control over their environment, which may be of greater interest to the researcher because of its empirical or theoretical importance. Ruback and Innes’s analysis suggests that for research to be high on conceptual verisimilitude, it must be high on both the number of policy variables investigated and on the utility of the dependent variables.

It is important to bear in mind that the structural, functional, and conceptual components of external validity are not entirely independent of one another; all three are necessary to accurately model a natural situation. One aspect of this interdependence is illustrated by Hendrick and Jones’ (1972) distinction between chronic and acute manipulations of independent variables. Chronic manipulations are those which are found in natural situations and which often result from an accumulation of small effects over time, have been experienced for some time, and are expected to continue into the future; examples are anxiety, self-esteem, and stress. In contrast, experiments normally involve acute manipulations,which result from a single event, occur relatively suddenly, and end with the research situation; in fact, ethical considerations require that they end then. For example, using a threat of electric shock to manipulate anxiety constitutes an acute manipulation of anxiety. Acute manipulations thus lack structural verisimilitude because of their time-limited nature. This time limitation may, in turn, call other aspects of ecological validity into question. Conceptual verisimilitude questions the equivalence of long-and short-term anxiety at the construct level, and finds they are probably not equivalent (for example, Spielberger, Vagg, Barker, Donham, & Westberry, 1980). Functional verisimilitude questions whether the processes involving long-and short-term anxiety are equivalent, and finds they are probably not (for example, Millman, 1968). One threat to ecological validity may therefore imply others. Conversely, conceptual verisimilitude may require structural verisimilitude. The study of policy-relevant variables, such as the impact of crowding on illness rates, may often be practical only in natural settings (for example, Ruback & Carr, 1984).

The more often that tests of a hypothesis result in similar findings when conducted in a variety of settings using a variety of procedures with a variety of participants over time and across cultures, the more confidence we can have in the generality of the hypothesis. Note that external validity is therefore a characteristic of a set of findings or of a theory, not of an individual study; individual studies function as tests of the generalizability and ecological validity of theories (Cronbach, 1975). This section looks at some of the issues involved in assessing the generalizability and ecological validity of research results.

By conducting multiple tests of a hypothesis, a researcher can determine the circumstances under which the hypothesis is supported and those under which it is not. This process allows the researcher not only to determine the boundary conditions of the hypothesis, but also to generate and test new hypotheses concerning the rules governing those conditions. Thus, one could interpret the finding that Americans’ stereotypes of nationality groups change over time (Karlins, Coffman, & Walters, 1969) as evidence of “psychology as history,” or one could use it to test hypotheses about the nature of stereotypes and why they change over time (Secord & Backman, 1974). In addition, replicating the effect of an independent variable using different operational definitions, settings, populations, and procedures enhances the construct validity of the principle being tested. The more varied the conditions under which the effect is replicated, the more likely it is that the effect observed is due to the abstract hypothetical construct than to the concrete conditions under which the research is carried out.

One indicator of a possible lack of generalizability of a hypothesis is an interaction effect in a factorial design: One independent variable has an effect only under certain conditions of the other independent variable. Conversely, the generalizability of an effect across an external validity variable such as setting, procedures, or participant characteristics can be tested by including that variable as a factor in the design. If, for example, sex of participant interacts with topic in an opinion conformity experiment (Eagly & Carli, 1981), then you know that sex differences don’t generalize across topics and that topic differences don’t generalize across women and men. The large number of factors that affect the external validity of research may lead you to despair of being able to generalize the results of any piece of research: After all, it would be impossible to control all these factors in one study. However, at least three steps can be taken: (1) include generalization factors, such as sex or race of participant, in the study’s design; (2) design research projects to systematically replicate findings as a test of their generalizability when the appropriate factors cannot be included in a single design; and (3) interpret the results of research in light of the limits its design places on generalization.

In trying to determine the ecological validity of a theory or of a set of research findings, you must ask two questions: To what degree is each of the components of ecological validity represented in the research on the issue, and what standard should be used to determine if a principle has been successfully replicated in a natural setting?

The components of ecological validity. If the issue of ecological validity is relevant to the evaluation of a theory or piece of research, then you must assess the degree to which the research exhibits conceptual, functional, and structural verisimilitude. On the conceptual level, you must determine the policy relevance of the independent variables and the utility of the dependent variables (see Chapter 5). On the functional level, you must decide how similar the psychological processes involved in the research setting are to those involved in the natural setting. On the structural level, you must evaluate the naturalism of the manipulations or measures of the independent variables, of the measures of the dependent variables, of the research population, and of the characteristics of the research setting. Remember that ecological validity is not an all-or-nothing decision: Each of the components (and subcomponents of structural verisimilitude) can vary along a continuum of similarity to the natural setting (Tunnell, 1977). For example, some populations used in research on a topic are quite similar to the natural populations to which the research might be applied; others are less similar. The amount of confidence that you can have in generalizing to populations not used in the research depends on the similarity of the research and natural populations. Such issues of degree of similarity apply to making generalizations to outcome, treatment, and setting variables that were not used in the research.

Success criteria. You must also decide what kind of outcome from a natural setting study indicates that a theory or principle has been successfully applied in the setting. Campbell (1986) notes that successful application or generalization of a theoretical principle or the results of a laboratory study can be defined in at least five ways:

1. |

Empirical results obtained in the field are identical to those obtained in the laboratory. |

2. |

The direction of empirical relationships found in the field are the same as those found in the laboratory. |

3. |

The conclusions drawn about a specific question are the same for field studies as they are for laboratory studies. |

4. |

The existence of a particular phenomenon can be demonstrated in the laboratory as well as the field. |

5. |

Data from the laboratory can be used to justify or support the application of a particular practice or program in an operational setting. (p. 270) |

Campbell believes that many people tend to think of ecological validity only in terms of the first meaning, but suggests that the third and fifth meanings may be the most useful because even exact replications rarely obtain results absolutely identical to those of the original study.

For at least the last half century, behavioral scientists have been engaged in a debate over the roles of laboratory and natural setting research in developing an externally valid body of knowledge. This section discusses two aspects of this debate: laboratory researchers’ views on the ecological validity of research and the relationship between external validity and internal validity.

The discussion of the structural component of external validity noted a number of factors that can limit the ecological validity of the results of laboratory research, such as the artificiality of the research setting and procedures and the widespread use of convenience samples from potentially unrepresentative populations. Some commentators have taken these characteristics of laboratory research as a priori evidence of its external invalidity (Argyris, 1980; Henrich et al., 2010). These critics take the position that if the conditions of research do not faithfully mimic the conditions of a natural setting in which the behavior or process being studied is found, then the results of the research lack external validity. In essence, these critics equate external validity with ecological validity.

As you might expect, researchers who engage in laboratory research do not share that view. This section will present four arguments that have been given in defense of traditional laboratory procedures: that ecological validity, especially when defined solely in terms of structure, is irrelevant to, and in some cases may hinder, the purposes of research, that ecological validity is an empirical question, that conducting research in natural settings does not guarantee its external validity in the sense of generalizability, and that the structural component of external validity is inappropriately given priority over the functional and conceptual components. This section also examines analog research, which attempts to enhance the functional verisimilitude of laboratory research, and considers the roles of scientists’ personal philosophies of science in the ecological validity debate.

Purposes of research. The defenders of the traditional laboratory experiment point out that research has many goals and that the laboratory environment is more conducive to achieving some goals, whereas the field environment is more conducive to achieving other goals. Specifically, these commentators point to four goals that are better pursued in the laboratory: testing causal hypotheses, falsifying theoretical propositions, dissecting complex phenomena, and discovering new phenomena.

Berkowitz and Donnerstein (1982) state that “laboratory experiments are mainly oriented toward testing some causal hypothesis … and are not carried out to determine the probability that a certain event will occur in a particular population” (p. 247). That is, laboratory research is carried out to test the validity of what one hopes are universal theoretical principles; whether members of a particular population undergoing a particular application of a theory in a particular setting show a particular response is an important question, but it is not the type of question asked by laboratory research. As Oakes (1972) wrote in regard to participant samples,

A behavioral phenomenon reliably exhibited is a genuine phenomenon, no matter what population is sampled in the research in which it is demonstrated. For any behavioral phenomenon, it may well be that members of another population that one could sample might have certain behavioral characteristics that would preclude the phenomenon being demonstrated with that population. Such a finding would suggest a restriction of the generality of the phenomenon, but it would not make it any less genuine. (p. 962)

In fact, very few researchers, either those who are laboratory oriented or those who are field oriented, would claim that their results would apply to all people in all situations; rather, they would say that it is the purpose of programmatic applied research carried out by people knowledgeable of the applied situation to determine the conditions governing the applicability of a theory (Cronbach, 1975).

A second purpose of experimentation is to allow falsification of invalid hypotheses (Calder, Phillips, & Tybout, 1981). If a laboratory experiment provides the most favorable conditions for the manifestation of a phenomenon and the phenomenon still does not occur, it is unlikely to occur under the usually less favorable natural conditions (Mook, 1983). For example, Higgins and Marlatt (1973) conducted a laboratory experiment to test the hypothesis that alcoholics drink to reduce tension and anxiety. They tried to establish conditions favorable to confirmation of the hypothesis by using threat of electric shock to induce an extremely high level of anxiety in the participants in their research, making alcoholic beverages readily available to participants, and eliminating the use of other forms of tension reduction such as escape from the situation. When their experiment failed to support the hypothesis, Higgins and Marlatt concluded that “threat of shock did not cause our subjects to drink under these circumstances. Therefore, the tension reduction hypothesis, which predicts that it should have done so, either is false or is in need of qualification” (p. 432). Conversely, one could demonstrate the strength of a phenomenon by showing that it occurs despite artificially strong barriers to it (Prentice & Miller, 1992).

Experiments can also be used to dissect complex naturally occurring variables into their component parts to determine which of the components are crucial to a variable’s relationship with another variable. This finer-grained knowledge increases understanding of the relationship and may help to tie it into a theoretical network (Mook, 1983). For example, by randomly assigning research participants to the roles of prisoner and guard in a simulated prison, Haney, Banks, and Zimbardo (1973) were able to remove the effects of self-selection from the role acquisition process and thereby study the influence of situational demands on behavior. Similarly, the artificial controls of laboratory research allowed Lowen and Craig (1968) to specify the reciprocal effects of leader and subordinate behavior.

A final purpose of experimentation is what Henshel (1980) calls its discovery function: seeking out previously unknown relationships between variables under conditions that do not exist in natural settings. Because experimental control permits the arrangement of variables in novel configurations, the researcher can create unique physical or social environments to answer “what if” questions. As Henshel puts it, the researcher “seeks to discover [relationships] that are capable of existing, if only the outside world provided the appropriate conditions” (p. 472). Henshel cites brain wave biofeedback as an area of research and application that developed through the discovery process—that is, of testing the effects of highly artificial conditions. He notes that research high in ecological validity would never have detected brain wave biofeedback: “Neither humans nor other organisms are capable of monitoring their own brain waves in the slightest extent without special, artificial arrangements. [The discovery] required experimenters who wondered what would happen if humans could see their own brain wave output” (p. 473; emphasis in original). Thye (2000) notes that this discovery function applies to the laboratory research conducted in all the sciences and that, like physicists and chemists, experimental social science researchers simply create testing grounds that are used to evaluate their theories. As he put it:

asking social scientists to use experiments or surveys that resemble social situations (e.g., graduation parties, assembly lines, or football games) is like demanding natural scientists use levers, weights, or lenses that resemble natural items (sticks, crude balances, or home-spun glass). One must wonder if fields from particle physics to cosmology would ever have advanced under such restrictions? Probably not. All scientists use the best tools they can to make theoretically informed decisions. Whether these tools are natural, artificial, or synthetic is just not relevant. (p. 1300, emphasis in the original)

Ecological validity as an empirical question. Several analysts of the ecological validity debate have pointed out that the ecological validity of research is fundamentally an empirical question (for example, Anderson, Lindsay, & Bushman, 1999). That is, the question of whether a particular finding can be applied to a specific setting or population is testable. Such tests have frequently supported the ecological validity of laboratory research. For example, Anderson et al. (1999) examined the results of 21 meta-analyses (see Chapter 19) that compared the average effect sizes found in laboratory and field research in psychology. Anderson et al. found that the average effect sizes for the lab and field studies were generally quite similar and were highly correlated, r =.73. They concluded that “the psychological laboratory is doing quite well in terms of external validity; it has been discovering truth, not triviality. Otherwise, correspondence between field and lab effects would be close to zero” (p. 8). Generalizability of results to a particular setting should therefore always be tested, never accepted or rejected out of hand.

Natural settings and generalizability. An often overlooked aspect of the ecological validity debate is that conducting research in a natural setting is no guarantee of its generalizability (Banaji & Crowder, 1989; Locke, 1986). That is, any research carried out in a natural environment is done so in a particular setting, with a particular set of participants, using a particular set of procedures, just as in laboratory research. Therefore, the results are no more or less likely than those of a laboratory experiment to apply to other settings (either natural or laboratory), participants, or procedures. For example, just as laboratory research has been described in McNemar’s (1946) classic phrase as “the science of the behavior of sophomores” (p. 333), Dipboye and Flanagan (1979) characterized natural setting research in industrial and organizational psychology as “a psychology of self-report by male, professional, technical, and management personnel in productive-economic organizations” (p. 146), reflecting the modal procedures, participants, and settings used in that field of applied research. As Oakes (1972) noted regarding participant populations, “any population one may sample is ‘atypical’ with respect to some behavioral phenomenon. But the point is that we cannot really say a priori what population is ‘more typical’” (p. 962; emphasis in original). Banaji and Crowder (1989) suggest that generalizability and ecological validity are independent dimensions of research and give examples of natural setting studies with low generalizability and of artificial setting studies with high generalizability.

Structural versus functional and conceptual verisimilitude. Locke (1986) states that “ecological representativeness of the type implied in the [ecological] validity thesis is an invalid standard” (p. 7) that focuses on structural issues while ignoring functional issues. In his view, to determine the applicability of research to natural settings one must identify the essential features of the settings that need to be replicated in the lab, such as essential participant, task, and setting characteristics. This process would not involve trying to reproduce the natural settings exactly but, rather, abstracting out of the settings those elements that are required for the phenomenon to occur. In Locke’s view, then, it is the functional component of external validity—the similarity of the psychological processes in the natural and research situations—that is the key to ecological validity because it allows for generalization across a variety of natural settings.

Analog research. Research that attempts to extract essential aspects of a natural setting and reproduce them in the laboratory is often referred to as analog research because it attempts to establish conditions that are analogous to those in the natural setting:

An analogue is designed to preserve an explicit relationship between the laboratory setting and some real-world situation of interest; for every feature of the external situation that is considered theoretically relevant, there is a corresponding feature contained in the laboratory situation. In this sense, an analogue is like a roadmap of a particular geographic region, where there is a one-to-one correspondence between features on the map and specific features of the actual terrain (e.g., highways, rivers, mountains, etc.) but where other features that exist in the natural setting (e.g., trees, houses) are not represented on the map. If the features represented in the analogue situation have been appropriately selected, participants’ responses to that situation should provide an accurate “mapping” of their responses to the corresponding situation in real life. (Crano & Brewer, 2002, p. 92)

The key feature of analog research is the theoretical relevance of the variables under investigation. These variables may or may not be operationalized in ways that reflect their natural manifestations, but analog research generally attempts to maximize mundane realism (or structural verisimilitude) while engaging participants’ interest and attention by maximizing experimental realism in ways that enhance functional verisimilitude. Emphasis on the theoretical relevance of the variables studied also enhances the conceptual verisimilitude of the research relative to the theory being tested. Interestingly, maintaining conceptual verisimilitude can lead to research procedures that appear to be of low structural verisimilitude. For example, Vrendenburg, Flett, and Krames (1993) suggest that college students constitute an ideal research population for testing theories concerning the role of stress in causing depression:

Being young and having a high chronic level of negative affective distress are two factors that increase the likelihood of experiencing a major depression. Because 1st-year college students tend to be quite young and the transition to college involves a great deal of stress, it seems that college student populations may be particularly appropriate for investigators interested in the initial development of depression. It cannot be denied that college students encounter many, if not all, of the major stressors believed to precipitate bouts of depression. (p. 335)

However, just as the structural component is not the defining criterion for external validity, neither are the functional and conceptual components. As noted earlier, there is no guarantee that any piece of research will apply to a specific set of circumstances. Only research conducted under those circumstances can validate a theoretical or empirical principle for a specific situation (for example, Yuille & Wells, 1991); other research can only suggest that the principle might apply.

Philosophies of science and naturalism in research. The debate over the external validity of laboratory research has been going on for over 50 years and is unlikely to be resolved easily or quickly. This situation exists because the debate may, to some extent, be a function of personal beliefs about the nature of scientific knowledge. Some people’s philosophies may bring them to prefer the laboratory approach, whereas other people’s philosophies may bring them to prefer research in natural settings (Kimble, 1984; Krasner & Houts, 1984). To the extent that the debate involves such basic philosophical differences, it may be irreconcilable. For example, Sears’s (1986) statement that Berkowitz and Donnerstein’s (1982) argument that “experimental, rather than mundane realism is sufficient to test causal hypotheses … seems less obvious to me than it does to them” (p. 520) appears to reflect a basic epistemological position. However, perhaps the debate should not be resolved: Some epistemologists contend that the truth is best found through vigorous debate among partisan adherents of opposing viewpoints (MacCoun, 1998), and debates about the advantages and disadvantages of various research methods keeps attention focused on conducting high-quality research (Ilgen, 1986).

Nonetheless, it is important to note that there is no necessary contradiction between the positions of the adherents of laboratory research and those of the adherents of naturalistic research; the difference is one of viewpoints. As noted at the beginning of this chapter, basic researchers are primarily interested in the extent to which results can be replicated under a variety of conditions; natural settings represent a subset of all the possible conditions under which an effect could be replicated. To the basic researcher, therefore, a natural setting study is just one more source of evidence about the validity and limitations of the theory being tested. Applied researchers, however, are more interested in a specific setting or category of settings, such as factories, and the people and events naturally found in that setting. To the applied researcher, then, natural setting research is the most useful research because it provides information about the specific setting of interest and the behavior of the people in that setting. The more general principles of behavior studied by the basic researcher are, to some extent, outside the applied researcher’s scope of interest, except as general guides and starting points for what might work in that setting.

The debate over how essential ecological validity is to behavioral science research tends to pass over a point that we made in Chapter 2: Both external validity, especially naturalism, and internal validity, especially control over extraneous variables, are desirable characteristics of research, but it is impossible to maximize both simultaneously. For example, enhancing the internal validity of a study by carefully controlling all possible sources of extraneous variance increases its artificiality, which can limit the generalizability and ecological validity of its results. Conversely, maximizing the ecological validity of a study by conducting it in a natural setting opens the door to threats to its internal validity, such as those discussed in Chapters 7 and 10. As McGrath (1981) wrote, “One cannot plan, or execute, flawless research. All strategies, all designs, all methods, are … flawed” (p. 209).

However, Cook and Campbell (1979) point out that although there will be a tradeoff between them, internal validity should take precedence over external validity when you design research. Whether the research is being conducted to test a theoretical proposition in a laboratory setting or to test the effectiveness of a treatment in a natural setting, the researcher’s most basic goal is to be able to draw valid conclusions about the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. Only by being able to rule out plausible alternative explanations for effects—that is, by maintaining appropriate standards of internal validity—can the researcher achieve this goal. No matter how ecologically valid a piece of research is, its results are useless if you cannot be confident of the accuracy of the conclusions drawn from them.