Open- and Closed-Ended Questions

Use the language of research participants

Ask only one question at a time

Avoid leading and loaded questions

Address sensitive topics sensitively

Advantages of Multi-Item Scales

Respondent interpretations of numeric scales

Suggestions for Further Reading

Questions for Review and Discussion

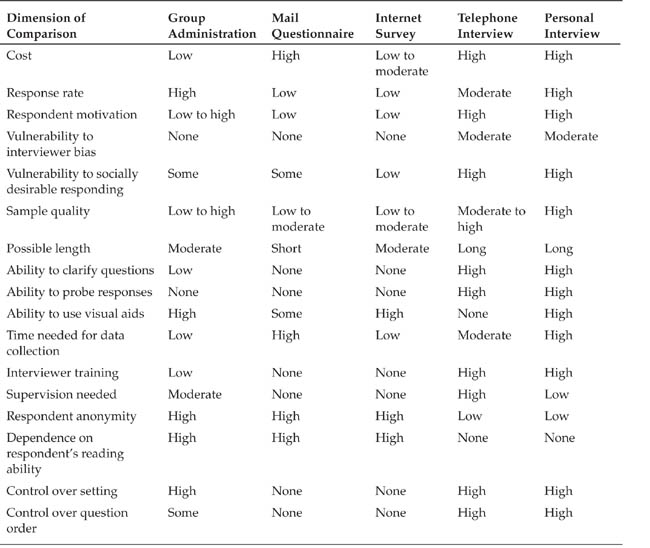

In the most general sense, survey research is the process of collecting data by asking people questions and recording their answers. Surveys can be conducted for a variety of purposes, two of which predominate. One purpose is the estimation of population parameters, or the characteristics of a population. For example, the goal of a survey might be to determine the percentage of people who hold supporting and opposing positions on social issues, such as nuclear power; the percentage who perform certain behaviors, such as smoking cigarettes; or the demographic characteristics of the population, such as sex, age, income, and ethnicity. The U. S. census, public opinion polls, and the periodic General Social Survey (GSS) conducted by the University of Chicago’s National Opinion Research Center are all surveys directed at estimating population parameters. The second purpose for which a survey might be conducted is hypothesis testing. Researchers might be interested in the correlations between the answers to questions or between characteristics of respondents and their answers. Surveys can be conducted specifically for the purpose of hypothesis testing, or researchers might use data from survey archives, such as those described in the next chapter, to test their hypotheses. Experiments can also be conducted by survey methods when the researcher manipulates independent variable by varying the information that participants receive: People in the different conditions of the independent variable receive versions of the survey that contain the information that defines the condition to which they are assigned.

Surveys can also be classified into two broad categories based on the way respondents are recruited. Respondents in sample surveys are selected in ways that are designed to produce a respondent sample whose characteristics closely mirror those of the population from which the sample was drawn. National public opinion polls and the GSS are examples of sample surveys: They use techniques described in the next chapter to obtain respondent samples from each region of the United States who reflect the gender, ethnic group, and age distributions of the population. Respondents in convenience surveys consist of members of whatever group or groups of people that the researcher found it convenient to sample from. Most self-report research in the behavioral sciences uses convenience surveys, primarily of college students. The data from sample surveys can be used either to estimate population parameters or to explore relationships between variables. Because the samples used in convenience surveys are not representative of a population, they cannot be used to estimate population parameters but are commonly used in hypothesis-testing research.

This chapter provides an overview of several key issues in survey research. We first describe the process of writing questions and creating question response formats, and the advantage of using multi-item scales, especially when measuring hypothetical constructs. We next discuss the problem of response biases and conclude with an overview of the principles of questionnaire design and administration. One chapter cannot cover all the information you would need to know before conducting survey research, so before getting started on your own survey research you should consult a specialized book on the topic.

Survey researchers collect data by asking questions. The questions, or items, are compiled into questionnaires that can be administered to respondents in a variety of ways, as discussed later in this chapter. These items are composed of two parts. The stem is the question or statement to which the research participant responds, and the response options are the choices offered to the respondent as permissible responses. Consider the following item:

The university should not raise tuition under any circumstances.

Agree |

Disagree |

In this example, “The university should not raise tuition under any circumstances” is the stem and “Agree” and “Disagree” are the response options. This section discusses stem (or question) writing, and the next section discusses formats for response options. The phrasing of the question is extremely important because differences in phrasing can bias responses. In fact, the issue of question phrasing is so important that entire books have been written on the topic (for example, Bradburn, Sudman, & Wansink, 2004). In this section we have space to touch on only a few of the major issues; see the suggested reading list at the end of the chapter for sources that can guide you on your own research.

Questions can be grouped into two broad categories. Open-ended questions, such as essay questions on an exam, allow respondents to say anything they want to say and to say it in their own words. Closed-ended questions, such as multiple-choice exam questions, require respondents to select one response from a list of choices provided by the researcher. Researchers generally prefer closed-ended questions because they can choose response options that represent categories that interest them and because the options can be designed to be easily quantified. However, open-ended questions are more useful than closed-ended questions in three circumstances. The first is when asking about the frequency of sensitive or socially disapproved behaviors. Bradburn and colleagues (2004), for example, found that people reported higher frequencies of a variety of drinking and sexual behaviors in response to open-ended questions than in response to closed-ended questions. A second circumstance is when you are unsure of the most appropriate response options to include in closed-ended questions on a topic or to use with a particular participant population. Schuman and Presser (1996) therefore recommend using open-ended questions in preliminary research and using the responses to those questions to design response options for closed-ended questions. This strategy can reveal response options the researchers did not think of. Conversely, the response options included in closed-ended questions might remind respondents of responses they might not think of spontaneously. We discuss this issue later in the chapter as well as the possibility that open-ended questions can assess some types of judgments more accurately than can closed-ended questions.

A major lesson survey researchers have learned is that the way in which a question is phrased can strongly affect people’s answers. Consider the two questions shown in Table 15.1. Half the respondents to surveys conducted in the late 1970s were asked the first question; the other half were asked the second question. Notice that adding the phrase “to stop a communist takeover” increased the approval rate for intervention from 17% to 36%. Let’s examine a few basic rules of question writing.

Use the language of the research participants. The questions used in survey research are usually written by people who have at least a college education and frequently by people who have a graduate education. As a result, the question writers’ vocabularies may differ significantly from those of their respondents in at least two ways. First, researchers use many technical terms in their professional work that are unknown or that have different meanings to people outside the profession. Using such terms in questions will usually result in confusion on the part of respondents. Second, researchers’ normal English vocabulary is likely to be larger than that of their participants, and using what might be called an intellectual vocabulary is another source of misunderstanding. As Converse and Presser (1986, p. 10) note, the “polysyllabic and Latinate constructions that come easily to the tongue of the college educated” almost always have simpler synonyms. For example, “main” can be used for “principal” and “clear” for “intelligible.” It is also wise to avoid grammatically correct but convoluted constructions such as “Physical fitness is an idea the time of which has come” (Fink & Kosecoff, 1985, p. 38). “An idea whose time has come” might irritate grammarians, but will be clearer to most people. When people fail to understand a question, they will interpret it as best they can and answer in terms of their interpretation (Ross & Allgeier, 1996). Consequently, respondents might not answer the question that the researcher intended to ask.

TABLE 15.1

Effect of Question Wording on Responses to Survey Questions

Question |

Percent in Favor of Sending Troops |

If a situation like Vietnam were to develop in another part of the world, do you think the United States should or should not send troops? |

17.4 |

If a situation like Vietnam were to develop in another part of the world, do you think the United States should or should not send troops to stop a communist takeover? |

35.9 |

Note: From Schuman and Presser (1996)

Because respondents may misunderstand or misinterpret questions, it is important to pretest questionnaires to assess people’s understanding of the questions. Samples of respondents from the population in which the questionnaire will be administered should be used for pretests. Sudman, Bradburm, and Schwarz (1996) describe a number of methods for assessing the comprehensibility of questionnaire items; Box 15.1 lists a few of them.

• |

Have respondents read each question, give their responses, and then explain how they decided on their responses. For example, “Tell me exactly how you arrived at your answer …how did you work it out … how exactly did you get to it?” (Sud-man, Bradburn, & Schwarz, 1996, p. 19). This technique is sometimes called the think aloud method. |

• |

Directly ask respondents what the item meant to them. For example, Ross and Allgeier (1996) asked their respondents, “What I would like you to do is tell me what you though the item was actually asking you. I’m only interested in your interpretation. What did you think this item was asking when you responded to it?” (p. 1593). |

• |

Ask respondents to define specific terms used in the items. Be sure to let them know that you are trying to identify unfamiliar words and terms, so “I don’t know” is an appropriate response. |

• |

When you administer the questionnaire to the research sample, for each item record the number of respondents who ask for clarification, give incomplete responses, or give responses that suggest they misinterpreted the item. |

Avoid unnecessary negatives. Using negative constructions in questions can lead to confusion. Consider this hypothetical example: “Do you agree or disagree that people who cannot read well should not be allowed to teach in public schools?” Whether respondents agree or disagree, it’s impossible to tell what they’re agreeing or disagreeing with. Although this is an extreme example, researchers are sometimes tempted to use negative constructions as a way of balancing questions to control for some people’s tendencies to agree with whatever position they are presented with. Very often, however, a little searching will turn up alternatives. If our example were changed to “Do you agree or disagree that only people who read well should be allowed to teach in public schools?” the meaning of the responses would be clearer.

Ask only one question at a time. A double-barreled question asks for two or more pieces of information at once. Consider the following question used in a national opinion poll in 1973: “Do you think that President Nixon should be impeached and compelled to leave office, or not?” (Wheeler, 1976, p. 182). Impeachment is the investigation and indictment of an official by the House of Representatives for an alleged offense; removal from office is a possible punishment if the official is found guilty after trial by the Senate. It would certainly be possible to agree that an official’s actions should be investigated but to disagree that removal from office is the appropriate penalty if the official is found guilty. This question also illustrates the vocabulary problem: A concurrent poll found that fewer than 50% of its respondents knew the meaning of impeachment (Wheeler, 1976).

Questions can become double-barreled through implication as well as the use of the word and. Consider the following example given by Lewin (1979, p. 137):

Your class functions as a stable, cohesive group, with a balance of leadership, which facilitates learning.

Always |

Often |

Sometimes |

Rarely |

Never |

This question asks for four pieces of information: perceived group stability, perceived group cohesiveness, type of leadership used in the group, and the effects of these factors, if any, on learning. Always ensure that each question used on a scale asks for only one piece of information; otherwise, you never know which question respondents are answering.

Avoid leading and loaded questions. A leading question implies that a certain response is desired. For example, “Do you agree that implies that agreement is the desired response. Similarly, the question “How attractive is this person?” suggests that they are, in fact, attractive; phrasing the question as “How attractive or unattractive is this person?” is less leading. Notice that the questions used as examples so far in this section have been balanced; that is, they suggest that either agreement or disagreement is an acceptable response (for example, “Do you think that … or not?” “Do you agree or disagree that …?”).

A loaded question uses emotional content to evoke a desired response, such as by appealing to social values, such as freedom, and terms with strong positive or negative connotations. Sudman and Bradburn (1982, p. 7) give this example:

Are you in favor of allowing construction union czars the power to shut down an entire construction site because of a dispute with a single contractor, thus forcing even more workers to knuckle under to union agencies?

Although this example is extreme, question loading can also be subtle. Rasinski (1989), for example, found that 64% of respondents to a series of surveys agreed that too little money was being spent on assistance to the poor, whereas only 23% agreed that too little was being spent on welfare. Clearly, welfare has a more negative connotation than assistance to the poor, even though both terms denote providing money to people in need. Table 15.2 lists some other pairs of phrases that Rasinski found to elicit different agreement rates.

Be specific. People’s belief systems are very complex. One result of this complexity is that people’s beliefs about general categories of objects can be very different from their beliefs about specific members of those categories. For example, you might like dogs in general but detest your neighbor’s mutt that barks all night. The effect of question specificity on response can be seen in the examples shown in Table 15.3, taken from a poll conducted in 1945. You must therefore ensure that your questions use the degree of specificity necessary for the purposes of your research.

Examples of Question Phrasings Receiving Different Agreement Rates in Surveys

Too little money is being spent on … |

Percent Agreeing |

Solving problems of big cities |

48.6 |

Assistance to big cities |

19.9 |

Protecting Social Security |

68.2 |

Social Security |

53.2 |

Improving conditions of African Americans |

35.6 |

Assistance to African Americans |

27.6 |

Halting rising crime rates |

67.8 |

Law enforcement |

56.0 |

Dealing with drug addiction |

63.9 |

Drug rehabilitation |

54.6 |

Note: From Rasinski (1989)

Do not make assumptions. It is easy to write questions that include unwarranted assumptions about the respondents’ characteristics or knowledge base. For example, the question “Do you agree or disagree with U.S. trade policy toward Canada?” assumes the respondent knows what that policy is. Similarly, asking, “What is your occupation?” assumes that the respondent is employed. People are quite willing to express opinions on topics with which they are unfamiliar; for example, Sudman and Bradburn (1982) reported that 15% of the respondents to one survey expressed opinions about a fictitious civil rights leader. Therefore, it is generally a good idea to verify that a respondent is familiar with a topic when asking questions about it. However, such verification questions should be tactful and not imply that the respondent should be familiar with the topic. Such an implication could lead the respondent to make up an opinion in order not to appear uninformed.

TABLE 15.3

Effect of Different Degrees of Question Specificity on Survey Responses From a Poll Conducted in 1945

Question |

Percent Answering Yes or Favor |

Do you think the government should give money to workers who are unemployed for a limited length of time until they can find another job? |

63 |

It has been proposed that unemployed workers with dependents be given $25 per week by the government for as many as 26 weeks during one year while they are out of work and looking for a job. Do you favor or oppose this plan? |

46 |

Would you be willing to pay higher taxes to give unemployed people up to $25 dollars a week for 26 weeks if they fail to find satisfactory jobs? |

34 |

Note: $25 in 1945 is the equivalent of $295 in 2010. From Bradburn, Sudman, and Wansink (2004), p. 7.

Address sensitive topics sensitively. Sensitive topics are those likely to make people look good or bad, leading respondents to underreport undesirable behaviors and to over-report desirable behaviors. Sudman and Bradburn (1982) suggest some ways to avoid biased responses, a few of which are shown in Box 15.2.

To avoid underreporting of socially undesirable behaviors:

• |

Imply that the behavior is common, that “everybody does it.” For example, “Even the calmest parents get angry with their children some of the time. Did your children do anything in the past week to make you angry?” |

• |

Assume the behavior and ask about frequency or other details. For example, “How many cans or bottles of beer did you drink during the past week?” |

• |

Ask respondents to define specific terms used in the items. Be sure to let them know that you are trying to identify unfamiliar words and terms, so “I don’t know” is an appropriate response. |

• |

Use authority to justify the behavior. For example, “Many doctors now think that drinking wine reduces heart attacks. How many glasses of wine did you drink during the past week?” |

To avoid over-reporting of socially desirable behaviors:

• |

Be casual, such as by using the phrase “Did you happen to …?” For example, “Did you happen to watch any public television programs during the past week?” Phrasing the question this way implies that failure to do so is of little importance. |

• |

Justify not doing something; imply that if the respondent did not do something, there was a good reason for the omission. For example, “Many drives report that wearing seat belts is uncomfortable and makes it difficult to reach switches on the dashboard. Thinking about the last time you got into a car—did you use a seat belt?” |

Note: From Sudman and Bradburn (1982).

As you can see, good questions can be difficult to write. This difficulty is one reason why it is usually better to try to find well-validated scales and questions than to create your own. If you must write your own questions, take care to avoid biases such as those described here.

Survey researchers ask questions to obtain answers. As noted earlier, these answers can be either open- or closed-ended. Most survey questions are designed to elicit closed-ended responses. In this section we discuss two issues related to closed-ended responses: levels of measurement and the relative merits of various closed-ended response formats.

Researchers use questionnaires to measure the characteristic of respondents: their attitudes, opinions, evaluations of people and things, their personality traits, and so forth. Measurement consists of applying sets of rules to assign numbers to these characteristics. Several different rules could be applied in any situation. To measure student achievement, for example, the researcher might use any of three rules: (a) Classify students as having either passed or failed, (b) rank order students from best to worst, or (c) assign each student a score (such as 0 through 100) indicating degree of achievement. Each rule provides more information about any particular student than did the preceding rule, moving from which broad category the student is in, to whom the student did better and worse than, to how much better or worse the student did. Because of these increasing amounts of information content, these rules are called levels of measurement (also sometimes referred to as scales of measurement).

Measurement levels. A variable can be measured at any of four levels of information content. From lowest to highest, these levels are called nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio.Nominal level measurement sorts people or things into categories based on common characteristics. These characteristics represent different aspects of a variable, such as gender or psychiatric diagnosis. As a result, nominal level data are usually reported in terms of frequency counts—the number of cases in each category—or percentage of cases in each category. To facilitate computerized data analysis, the categories are often given numbers (or scores); for example, “female = 1 and male = 2.” These numbers are completely arbitrary. In this example, someone receiving a score of 2 does not have more gender than someone receiving a score of 1; he is only different on this characteristic.

Ordinal level measurement places people or things in a series based on increases or decreases in the magnitude of some variable. In the earlier example, students were arranged in order of proficiency from best to worst, as in class standings. As a result, ordinal level data are usually reported in terms of rankings: who (or what) is first, second, and so forth. Notice that while ordinal level measurement provides comparative information about people, such as “Mary did better than Phil,” it does not quantify the comparison. That is, it does not let you know how much better Mary did. Because of this lack of quantification, one cannot mathematically transform ordinal level data, that is, perform addition, subtraction, multiplication, or division. As a result, most inferential statistics, such as the t test, which are based on these transformations, are usually considered to be inappropriate for use with ordinal level data.

Interval level measurement assigns numbers (scores) to people and things such that the difference between two adjacent scores (such as 1 and 2) is assumed to represent the same difference in the amount of a variable as does the between any other two adjacent scores (such as 3 and 4). In other words, the people using an interval level measure perceive the intervals between scores to be equal. Thus, if Chris scores 5 on a variable measured at the interval level, Mary scores 3, and Phil scores 1, we can say that Mary scored higher than Phil to the same degrees that Chris scored higher than Mary. For this reason, interval level measures are used to most hypothetical constructs, such as personality traits, attitudes, beliefs, psychiatric symptoms, and so forth.

In addition, interval level scores can be added to and subtracted from each other, multiplied and divided by constants, and have constants added to or subtracted from them; they cannot, however, be multiplied or divided by each other. For example, we could not say that Mary’s score was three times higher than Phil’s or that someone with a score of 20 on the Beck (1972) Depression Inventory is twice as depressed as someone with a score of 10. These transformations are impossible because interval level scores lack a true zero point; that is, the variable being measured is never totally absent in an absolute sense. For example, in women’s clothing, there is a size zero. Clearly, everyone has a clothing size; “size 0” is merely an arbitrary designation indicating “extremely small;” it does not indicate the total absence of size. Similarly, someone who wears a size 14 is not twice as big as someone who wears a size 7; such multiplicative comparisons are meaningless on interval-level scales.

Ratio level measurement, like interval level measurement, assigns equal interval scores to people or things. In addition, ratio measures have true zero points, and so can be multiplied and divided by each other. Therefore, it is appropriate to say that a ratio level score of 10 represents twice as much of a variable as does a score of 5. Some ratio level measures used in psychological research include the speed and frequency of behavior, the number of items recalled from a memorized list, and hormone levels. However, most measures of psychological states and traits and of constructs such as attitudes and people’s interpretations of events are interval level at best.

There are at least three reasons why understanding the measurement level of your items is important: it influences the amount of information obtained, it affects which statistical tests are appropriate, and it relates to the ecological validity of your findings. It is important to bear these considerations in mind when choosing a level of measurement.

Information content. Higher level measures contain more information than do lower level measures; they also contain all the information lower levels provide. For example, you could measure people’s heights in feet and inches and make ratio level comparisons, such as Mary is 1.2 times taller than Peter (ratio level); you can also measure height but not make ratio comparisons (interval level). Another option is to use the original measurement to rank people by height (ordinal level) or classify them as short or tall (nominal level). You cannot go the other direction; for example, if you ask people to classify themselves as short or tall, you cannot use this information to estimate actual their heights. As a general rule, you should collect data using the highest level of measurement possible.

TABLE 15.4

Hypothetical Opinion Data

Analyzing these data at the nominal level and at the interval level lead to different conclusions. |

||

|

Group A |

Group B |

Nominal Level Data |

|

|

Favor |

50% |

50% |

Oppose |

50% |

50% |

Interval Level Data |

|

|

Strongly favor |

2 |

16 |

Moderately favor |

2 |

2 |

Slightly favor |

16 |

2 |

Slightly oppose |

2 |

16 |

Moderately oppose |

2 |

2 |

Strongly oppose |

16 |

2 |

This difference in information content has two implications. First, the conclusions you can validly draw on the basis of measures constructed at one level of measurement, such as ratio, would be invalid if drawn on the basis of a lower level of measurement, such as interval. For example, you can say things such as “Group A improved twice as much as Group B” only if a ratio level measure is used. Second, higher level measures tend to be more sensitive to the effects of independent variables than are lower level measures. Consider the following hypothetical example, which uses the data shown in Table 15.4. Researchers conduct a study comparing the opinions of two groups of people (perhaps liberals and conservatives) on a political issue. Members of the groups are asked whether they favor or oppose a particular position on the issue, with the results shown in the top part of Table 15.4. Given this outcome, the researchers would conclude that there is no difference in opinion between the groups: 50% of the people in each group favor the position and 50% oppose it. If, however, the researchers asked people to put their opinions into one of the six categories shown in the bottom part of Table 15.4, with the frequency of response as shown for each category, they can analyze their results as interval level data. They would then conclude that the members of Group B have more favorable opinions than the members of Group A, p = .002. A difference was detected in the second case but not the first because the interval level measure contained more information than the nominal level measure, in this case information about the respondents’ relative degree of favorability toward the issue.

Statistical tests. Assumptions underlie statistical tests. The t-test, for example, assumes that the scores in the two groups being compared are normally distributed. However, nominal level measures are not normally distributed, and ordinal level data frequently are not, and so violate this assumption (as well as others). Therefore, some authorities hold that one can only use statistics that are designed for a particular level of measurement when using data at that level. Other authorities, however, hold that there is no absolute relationship between level of measurement and statistics. See Michell (1986) for a review of this debate.

On a more practical level, statisticians have investigated the extent to which the assumptions underlying a particular statistic can be violated without leading to erroneous conclusions (referred to as the robustness of a statistic). The results of this research indicate that under certain conditions, ordinal and dichotomous (two-value nominal) data can be safely analyzed using parametric statistics such as the t-test and analysis of variance (Davison & Sharma, 1988; Lunney, 1970; Myers, DiCecco, White, & Borden, 1982; Zumbo & Zimmerman, 1993). Before applying parametric statistics to nonparametric data, however, you should carefully check to ensure that your data meet the necessary conditions.

Ecological validity. As we saw in Chapter 8, the issue of ecological validity deals with the extent to which a research setting resembles the natural setting to which the results of the research are to be applied. Ecological validity is related to levels of measurement because the natural level of measurement of a variable may not contain enough information to answer the research question or may not be appropriate to the statistics the researcher wants to use to analyze the data. The researcher then faces a choice between an ecologically valid, but (say) insensitive, measure and an ecologically less valid, but sufficiently sensitive, measure. Consider, for example, research on juror decision making. The natural level of measurement in this instance is nominal: A juror classifies a defendant as guilty or not guilty. A researcher conducting a laboratory experiment on juror decision processes, however, might want a more sensitive measure of perceived guilt and so might ask subjects to rate their belief about how likely or unlikely it is that the defendant is guilty on a 7-point scale (interval level measurement). The researcher has traded off ecological validity (the measurement level that is natural to the situation) to gain sensitivity of measurement. As discussed in Chapter 2, such tradeoffs are a normal part of the research process and so are neither good nor bad per se. However, researchers should make their tradeoffs only after carefully weighing the relative gains and losses resulting from each possible course of action. Sometimes the result of this consideration is the discovery of a middle ground, such as using both nominal and interval level measures of juror decisions.

There are four categories of closed-ended response formats, commonly referred to as rating scales: the comparative, itemized, graphic, and numerical formats. Let’s look at the characteristics of these formats.

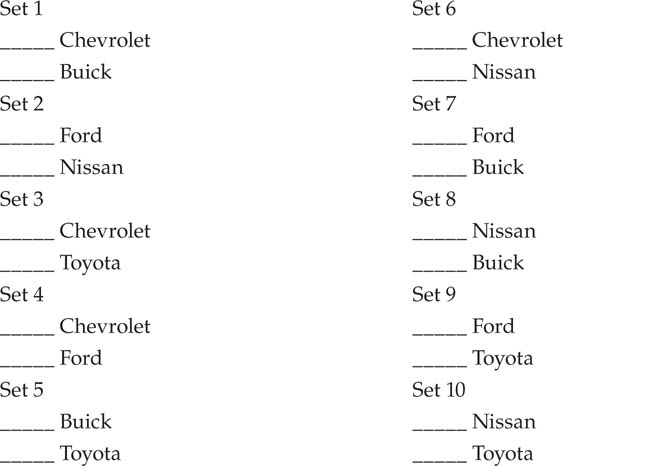

Instructions: Listed below are pairs of brand names of automobiles. For each pair, indicate the brand you think is of higher quality by putting an “X” on the line next to its name. Please make one choice in each pair and only one choice per pair; if you think the choices in a pair are about equal, mark the one you think is of higher quality even if the difference is small.

Comparative rating scales. In comparative scaling, respondents are presented with a set of stimuli, such as five brands of automobiles, and are asked to compare them on some characteristic, such as quality. Comparative scaling can be carried out in two ways. With the method of paired comparisons, raters are presented with all possible pairings of the stimuli being rated and are instructed to select the stimulus in each pair that is higher on the characteristic. Box 15.3 shows a hypothetical paired comparisons scale for five brands of automobiles. The score for each stimulus is the number of times it is selected. A major limitation of the method of paired comparisons is that it becomes unwieldy with a large number of stimuli to rate. Notice that with five stimuli, the scale in Box 15.3 had to have 10 pairs; the number of required pairs is n(n - 1)/2, where n is the number of stimuli. Consequently, 20 stimuli would require 190 pairs. With a large number of similar judgments to make, people can become bored and careless in their choices. Although there is no absolute rule about the maximum number of stimuli to use in the method, Crano and Brewer (2002) suggest no more than 10 (resulting in 45 pairs).

One solution to the problem of numerous pairs of stimuli lies in the method of rank order. With this method, respondents are given a list of stimuli and asked to rank them from highest to lowest on some characteristic. However, selecting the proper ranking for each stimulus can be a daunting task for respondents who are faced with a large number of stimuli. One way to simplify the task is to have respondents alternately choose the best and worst stimulus relative to the characteristic being rated. For example, if respondents had to rank 20 colors from the most to least pleasing, you would have them first choose their most and least preferred of the 20 colors, assigning those colors ranks 1 and 20, respectively. You would then have them consider the remaining 18 colors and choose their most and least preferred of those, giving those colors ranks 2 and 19, respectively. The process continues until all colors have been chosen.

Three conditions must be met for comparative scaling to provide reliable and valid results (Crano & Brewer, 2002). First, the respondents must be familiar with all the stimuli they compare. If a respondent is not familiar with a stimulus, the ranking of that stimulus will be random and therefore not reflect where it stands on the characteristic. For example, people who have never driven Fords cannot judge their quality relative to other brands of automobiles. Second, the characteristic on which the stimuli are being rated must be unidimensional; that is, it must have one and only one component. Note that the example in Box 15.3 violates this rule: automobile quality is made up of many components, such as physical appearance, mechanical reliability, seating comfort, the manufacturer’s reputation, and so forth. If a rating characteristic has several components, you have no way of knowing which component any respondent is using as a basis for making ratings. To the extent that different respondents base their ratings on different components, the ratings will be unreliable. This situation is similar to the specificity problem in question phrasing. Finally, the respondents must completely understand the meaning of the characteristic being rated. For example, when rating automobiles on mechanical reliability, each respondent must define reliability in the same way. It is therefore best if the researcher defines the characteristic being rated for the respondents.

Notice that comparative scaling results in data at the ordinal level of measurement. Consequently, the ratings represent relative rather than absolute judgments. That is, a stimulus that raters perceive to be mediocre might be ranked highest because it is better than any of the others despite its low absolute quality: It might be seen as “the best of a bad lot.”

Itemized rating scales.Itemized rating scales are multiple-choice questions: The item stem is in the form of a question, and the respondent chooses an answer from the options the researcher provides. A primary use of itemized scales is for classification—you can ask research participants to classify themselves as to sex, marital status, or any other variable of interest. Itemized scales can also be used to assess hypothetical constructs. Harvey and Brown (1992) present a theory of social influence that postulates five influence styles that every person uses to some degree. The degree to which any person uses each style is assessed with a scale composed of a set of social influence situations; each situation is followed by a set of possible responses to the situation. Each response represents one of the social influence styles. For example,

If I have made a suggestion or proposal and a person reacts negatively to it, I am likely to

a. |

Accept the person’s position and try to reexamine my proposal, realizing that our differences are largely due to our individual ways of looking at things, rather than take the reaction as a personal affront. |

b. |

Suggest the best course of action and make clear the results of not following that course of action. |

c. |

Feel upset about the disagreement but will go along with the other person’s ideas and allow him or her to express ideas fully. |

d. |

Point out the requirements of the situation but avoid becoming involved in fruitless argument. |

e. |

Search for a compromise position that satisfies point of view. |

(Harvey & Brown, 1992, p. 147)

Respondents choose the response most similar to the one they would make in the situation. Respondents’ scores for each style can be calculated as the total number of times that a response indicative of a style was chosen.

Itemized rating scales generally provide data at the nominal level of measurement. The data can become ordinal if choices representing a single characteristic are cumulated across items, as in the Harvey and Brown (1992) example. People can then be ranked on how often they chose the dimension as characteristic of themselves. Itemized rating scales can also provide ordinal level data if the response options are ordered along some dimension; for example,

Put an X on the line next to the phrase that best describes your political orientation:

_____ |

Very conservative |

_____ |

Moderately conservative |

_____ |

Slightly conservative |

_____ |

Slightly liberal |

_____ |

Moderately liberal |

_____ |

Very liberal |

Itemized rating scales must be developed carefully to ensure that all the relevant response options are presented to research participants. Failure to include all options will reduce the validity of the measure in either of two ways. First, respondents may skip the item because it doesn’t include a response option that accurately reflects their viewpoint. For example, when asked to choose from a list of five options the most important thing for children to learn to prepare for life—to obey, to be well liked, to think for themselves, to work hard, and to help others who need help—62% of the respondents to a survey chose “to think for themselves.” However, when another sample of respondents was asked the same question in an open-ended format, “to think for themselves” was mentioned by only 5% of the respondents. It ranked seventh in frequency of being mentioned; none of the first six characteristics mentioned were on the itemized list (Schuman & Presser, 1996). Alternatively, they may choose one of the options in the list even though that option differs from their actual viewpoint because they think they have to choose something, even it is not a completely accurate representation of their viewpoint. An incomplete list of options can also lead to biased research results that confirm old stereotypes rather than provide new knowledge. As Bart (1971) pointed out, allowing women to describe their sexual roles only as “passive,” “responsive,” “aggressive,” “deviant,” or “other” does not allow for responses such as “playful,” “active,” and so forth.

FIGURE 15.1

Examples of Graphic Rating Scales.

Graphic rating scales. With graphic rating scales, (also called visual analog scales), people indicate their responses pictorially rather than by choosing a statement as with itemized rating scales or, as we will see, by choosing a number with numerical rating scales. Figure 15.1 shows some examples of graphic rating scales. With the feeling thermometer—Figure 15.1(a)—respondents rate their evaluations of a stimulus, such as a political candidate, from warm (favorable) to cold (unfavorable); respondents indicate their feelings by drawing a line across the thermometer at the appropriate point. The simple graphic rating scale—Figure 15.1(b)—is used in the same way as the feeling thermometer: The respondent marks the line at the appropriate point. The scale is scored by measuring the distance of the respondent’s mark from one end of the line. The segmented graphic rating scale—Figure 15.1(c)—divides the line into segments; the respondent marks the appropriate segment. This format simplifies scoring because a numerical value can be assigned to each segment. The Smiley Faces Scale, Figure 15.1(d), (Butzin & Anderson, 1973) can be used with children who are too young to understand verbal category labels or how to assign numerical values to concepts. As with the segmented graphic rating scale, the researcher can give each face a numerical value for data analysis.

Indicate your current mood by circling the appropriate number on the following scale:

How would you rate your performance on the last test?

The university should not raise tuition under any circumstances.

Numerical rating scales. With numerical rating scales, respondents assign numerical values to their responses. The meanings of the values are defined by verbal labels called anchors. Box 15.4 shows some hypothetical numerical rating scales. There are three elements to the design of a numerical rating scale: the number of scale points, the placement of the anchors, and the verbal labels used as anchors.

In principle, a numerical rating scale can have from 2 to an infinite number of points. In practice, the upper limit seems to be 101 points (a scale from 0 to 100). Two factors determine the number of points to use on a scale. The first is the required sensitivity of measurement. A sensitive measure can detect small differences in the level of a variable; an insensitive measure can detect only large differences. In general, scales with more rating points are more sensitive than scales with only a few points. More points allow the raters finer gradations of judgment. For example, a 2-point attitude scale that allows only “Agree” and “Disagree” as responses is not very sensitive to differences in attitudes between people—those who agree only slightly are lumped in with those who agree strongly and those who disagree only slightly with those who disagree strongly. If you are studying the relationship between attitudes and behavior, and if people with strongly held attitudes behave differently from people with weakly held attitudes, you will have no way of detecting that difference because people with strongly and weakly held attitudes are assumed to be identical by your scale. In addition, respondents might be reluctant to use a scale they think does not let them respond accurately because there are too few options. People sometimes expand scales that they perceive as being too compressed by marking their responses in the space between two researcher-supplied options.

The second factor related to the number of scale points is the usability of the scale. A very large number of scale points can be counterproductive. Respondents can become overwhelmed with too many scale points and mentally compress the scale to be able to use it effectively. One of us (Whitley) once found, for example, that when he had people respond to a scale ranging from 0 to 100, many compressed it to a 13-point scale using only the 0, 10, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 75, 80, 90, and 100 values. Researchers have found that people generally prefer scales that have from 5 to 9 points (Cox, 1980). With fewer than 5 points, people feel they cannot give accurate ratings; with more than 9 points, they feel they are being asked to make impossibly fine distinctions. In addition, although the reliability of a scale increases as points are added from 2 to 7, there is little increase after 7 points (Cicchetti, Showalter, & Tyrer, 1985). A scale of 5 to 9 points is therefore probably optimal.

As Box 15.4 shows, the anchors for a numerical rating scale can be placed only at the end points or at the end and intermediate points. The use of intermediate anchors has two advantages. First, they more clearly define the meaning of the scale for respondents. When anchors are used only at the end points, respondents might be unsure of the meaning of the difference between two points on the scale. From the respondent’s point of view, it can be a question of “What am I saying if I choose a 3 instead of a 4?” Perhaps because of this greater clarity of meaning, numerical rating scales that have anchors at each scale point show higher reliability and validity than scales with other anchoring patterns (Krosnick, 1999b).

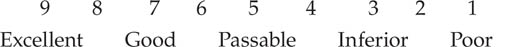

The second advantage of intermediate anchors is that, in combination with the proper selection of labels for the anchors, they can increase the level of measurement of the scale. When numerical scales have only end point anchors or have intermediate anchors arbitrarily chosen by the researcher, ordinal level measurement results. There is no basis for assuming that simply because the mathematical differences between the scale points are equal that respondents perceive them as psychologically equal. However, the verbal labels used as anchors can be chosen so that the difference in meaning between any two adjacent anchors is about equal to the difference in meaning between any other two adjacent anchors (Bass, Cascio, & O’Connor, 1974; Spector, 1976, 1992). Table 15.5 shows some approximately equal interval anchors for 5-point scales of agreement—disagreement, evaluation, frequency, and amount. These 5-point scales can be expanded to 9-point scales by providing an unlabeled response option between each pair of labeled options, as shown in the second scale in Box 15.4. Bass et al. (1974) and Spector (1976) list additional anchor labels and their relative scale values.

Which response format is best? The answer to that question depends primarily on the purpose of the rating scale. If the purpose is to determine the relative position of the members of a set of stimuli along a dimension, then a comparative format is best. The method of paired comparisons is better with a small number of stimuli, and ranking is better with a large number of stimuli. If the purpose is to locate an individual or a single stimulus along a dimension, a numerical rating scale with equal interval anchors is probably best because it can provide interval level data. Itemized scales place people and stimuli into specific categories. Despite these differences, the results of stimulus ratings using different formats are highly correlated (Newstead & Arnold, 1989), suggesting that format might not have a large effect on the conclusions drawn about relationships between variables.

Anchors for 5-Point Equal-Appearing Interval Scales of Agreement-Disagreement, Evaluation, Frequency, and Amount

Scale Point |

Agreement-Disagreementa |

Evaluationa |

Frequencya |

Amountb |

1 |

Very much |

Excellent |

Always |

All |

2 |

On the whole |

Good |

Frequently |

An extreme amount |

3 |

Moderately |

Passable |

Sometimes |

Quite a bit |

4 |

Mildly |

Inferior |

Seldom |

Some |

5 |

Slightly |

Terrible |

Never |

None |

aFrom Spector (1992), p. 192

bFrom Bass, Cascio, and O’Connor (1974), p. 319

A multi-item scale is composed of two or more items in rating scale format, each of which is designed to assess the same variable. A respondent’s scores on the items are combined—usually by summing or averaging—to form an overall scale score. A multi-item scale can be composed of two or more multi-item subscales, each of which measures a component of a multidimensional variable. A self-esteem scale, for example, could have subscales for global self-esteem, social self-esteem, academic self-esteem, and so forth. Each subscale would provide a subscale score for the component that it measures. In this section we discuss the advantages of using multi-item scales and describe the four types of these scales.

Multi-item scales have several advantages over single items as measures of hypothetical constructs. First, as just noted, multi-item scales can be designed to assess multiple aspects of a construct. Depending on the research objective and the theory underlying the construct, the subscale scores can be either analyzed separately or combined into an overall scale score for analysis. A second advantage of multi-item scales is that the scale score has greater reliability and validity than does any one of the items of which it is composed. This increased reliability and validity derive from the use of multiple items. Each item assesses both true score on the construct being assessed and error. When multiple items are used, aspects of the true score that are missed by one item can be assessed by another. This situation is analogous to the use of multiple measurement modalities discussed in Chapter 6. Generally speaking, as the number of items on a scale increases, so does the scale’s reliability and validity, if all the items have a reasonable degree of reliability and validity. Adding an invalid or unreliable item decreases the scale’s reliability and validity.

Finally, multi-item scales provide greater sensitivity of measurement than do singleitem scales. Just as increasing the number of points on an item can increase its sensitivity, so can increasing the number of items on a scale. In a sense, multi-item scales provide more categories for classifying people on the variable being measured. A single 9-point item can put people into 9 categories, one for each scale point; a scale composed of five 9-point items has 41 possible categories—possible scores range from 5 to 45—so that finer distinctions can be made among people. This principle of increased sensitivity applies to behavioral measures as well as self-reports. Let’s say that you are conducting a study to determine if a Roman typeface is easier to read than a Gothic typeface. If you asked participants in the research to read just one word printed in each typeface, their responses would probably be so fast that you could not detect a difference if one existed. However, if you had each participant read 25 words printed in each typeface, you might find a difference in the total reading time, which would represent the relative difficulty of reading words printed in the two typefaces.

Multi-item scales can take many forms. In this section we describe four major types: Likert scales, Thurstone scales, Guttman scales, and the semantic differential.

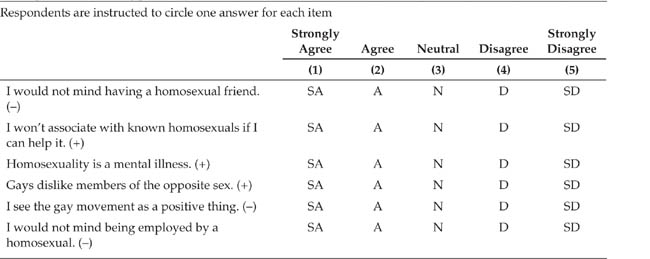

Likert scales.Likert scales are named for their developer, Rensis Likert (pronounced “Lick-urt”). Also known as summated rating scales, they are, perhaps, the most commonly used form of multi-item scale. A Likert scale presents respondents with a set of statements about a person, thing, or concept and has them rate their agreement or disagreement with the statements on a numerical scale that is the same for all the statements. To help control for response biases, half the statements are worded positively and half are worded negatively. Respondents’ scores on a Likert scale are the sums of their item responses. Table 15.6 shows some items from Kite and Deaux’s (1986) Homosexuality Attitude Scale. The numbers in parentheses by the anchors indicate the numerical values assigned to the response options; the plus and minus signs in parentheses after the items indicate the direction of scoring. Items with minus signs are reverse scored; that is, their numerical values are changed so that a high number indicates a higher score on the characteristic being assessed. In the example in Table 15.6, 1 would become 4, 2 would become 3, 3 would remain 3 because it is in the center of the scale, 4 would become 2, and 5 would become 1. Reverse scoring can be accomplished by using the formula R = (H + L) -I, where R is the reversed score, H is the highest numerical value on the scale, L is the lowest value, and I is the item score.

TABLE 15.6

Example of a Likert-Type Scale

Note: Respondents do not see the information in parentheses. From Kite and Deaux (1986).

As Dawis (1987) notes, the term Likert scale is frequently misused to refer to any numerical rating scale with intermediate anchors. However, Likert scaling is defined by the process by which items are selected for the scale, not by the response format. Only a scale with items that have been selected using the following four steps is a true Likert scale:

1. |

Write a large number of items representing the variable to be measured. The items represent the extremes of the variable, such as high or low self-esteem; moderate levels of the variable will be assessed as low levels of agreement with these extremes. The items have a numerical rating scale response format with intermediate anchors. |

2. |

Administer the items to a large number of respondents. Dawis (1987) suggests at least 100, but some statistical procedures that can be used for item selection, such as factor analysis, require more respondents (recall Chapter 12). Record respondents’ item scores and total scale scores. |

3. |

Conduct an item analysis. This analysis selects the items that best discriminate between high and low scorers on the scale; items that discriminate poorly are thrown out. This procedure ensures the internal consistency of the scale. The criterion for item selection is the item-total correlation: the correlation of the item score with a modified total score; the total score is modified by subtracting the score of the item being analyzed. No item with an item-total correlation below. 30 should be used in the final version of the scale (Robinson, Shaver, & Wrightsman, 1991a). |

4. |

The items with the highest item-total correlations comprise the final scale. There should be a sufficient number of items to provide an internal consistency coefficient of at least. 70 (Robinson et al., 1991a). |

An important assumption underlying Likert scale construction is that the scale is unidimensional; if the scale assesses a multidimensional construct, the assumption is that each subscale is unidimensional. That is, every item on the scale or subscale measures just one construct or just one aspect of a multidimensional construct. When the items on a scale measure more than one aspect of a construct, the meaning of the overall scale score can be ambiguous. Assume, for example, that a self-esteem scale measures both social and academic self-esteem. There are two ways for a respondent to get a middle-range score on the scale: by scoring in the middle on both aspects of self-esteem or by scoring high on one and low on the other. These two types of scores define self-esteem differently; they are not equally valid unless the theory of self-esteem on which the scale is based holds that the distinction between these aspects of self-esteem is unimportant. The number of dimensions represented in a scale can be investigated using factor analysis. Factor analysis of a Likert scale should result in one factor if the items were intended to measure only one construct, or one factor for each aspect of the construct if the items were intended to form subscales measuring different aspects of the construct. DeVellis (2003) presents a detailed description of the development of a Likert scale.

The popularity of the Likert approach to scaling is due to its possessing several desirable features, one or more of which are absent in the other approaches to scaling. First, Likert scales are easy to construct relative to other types of scales. Even though the Likert process has several steps, other processes can be much more laborious. Second, Likert scales tend to have high reliability, not surprising given that internal consistency is the principal selection criterion for the items. Third, Likert scaling is highly flexible. It can be used to scale people on their attitudes, personality characteristics, perceptions of people and things, or almost any other construct of interest. The other scaling techniques are more restricted in the types of variables with which they can be used, as you’ll see in the next two sections. Finally, Likert scaling can assess multidimensional constructs through the use of subscales; the other methods can assess only unidimensional constructs.

Thurstone scales. Louis Thurstone was the first person to apply the principles of scaling to attitudes. Thurstone scaling, like Likert scaling, starts with the generation of a large number of items representing attitudes toward an object. However, these items represent the entire range of attitudes from highly positive through neutral to highly negative, in contrast to Likert items, which represent only the extremes. Working independently of one another, 20 to 30 judges sort the items into 11 categories representing their perceptions of the degree of favorability items express. The judges are also instructed to sort the items so that the difference in favorability between any two adjacent categories is equal to that of any other two adjacent categories; that is, they use an interval-level sorting procedure. The items used in the final scale must meet two criteria: (a) They must represent the entire range of attitudes, and (b) they must have very low variance in their judged favorability. Respondents are presented with a list of the items in random order and asked to check off those they agree with; they do not see the favorability ratings. Respondents’ scores are the means of the favorability ratings of the items they chose. Sample items from one of Thurstone’s (1929) original attitude scales are shown in Table 15.7 along with their scale values (favorability ratings).

TABLE 15.7

Example of a Thurstone Scale

Scale Value |

Item |

1.2 |

I believe the church is a powerful agency for promoting both individual and social righteousness. |

2.2 |

I like to go to church because I get something worthwhile to think about and it keeps my mind filled with right thoughts. |

3.3 |

I enjoy my church because there is a spirit of friendliness there. |

4.5 |

I believe in what the church teaches but with mental reservations. |

6.7 |

I believe in sincerity and goodness without any church ceremonies. |

7.5 |

I think too much money is being spent on the church for the benefit that is being derived. |

9.2 |

I think the church tries to impose a lot of worn-out dogmas and medieval superstitions. |

10.4 |

The church represents shallowness, hypocrisy, and prejudice. |

11.0 |

I think the church is a parasite on society |

Note: |

On the actual questionnaire, the items would appear in random order and the scale would not be shown. From Thurstone (1929). |

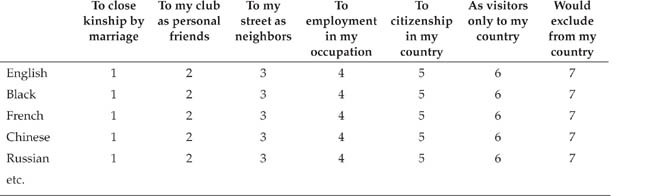

Bogardus (1925) Social Distance Scale

Directions: For each race or nationality listed, circle the numbers representing each classifi cation to which you would be willing to admit the average member of that race or nationality (not the best members you have known nor the worst). Answer in terms of your first feelings or reaction.

Note: Adapted from Bogardus (1925), p. 301.

Thurstone scales are rarely seen today, primarily because of their disadvantages relative to Likert scales. Thurstone scales are more laborious to construct than Likert scales and they tend to produce less reliable scores than Likert scales of the same length (Tittle & Hill, 1967). In addition, Thurstone scaling assumes that the attitude being assessed is unidimensional; the technique provides no way of to set up subscales for different aspects of an attitudes. A third limitation inherent in Thurstone scaling is that the judges’ attitudes influence their assignment of scale values to items (Hovland & Sherif, 1952): People rate statements that are close to their own opinions more favorably than divergent opinions, despite instructions to “be objective.” It is therefore essential that judges represent a cross-section of opinions on the attitude being scaled. Finally, the scale values that judges assign to items can change over time; Dawes (1972), for example, found some significant changes in the rated severity of crimes from 1927 to 1966. Such changes limit the “reusability” of Thurstone scales.

Guttman scales. With a Guttman scale (named for Louis Guttman, who developed the theory underlying the technique), respondents are presented with a set of ordered attitude items designed so that a respondent will agree with all items up to a point and disagree with all items after that point. The last item with which a respondent agrees represents the attitude score. The classic example of a Guttman scale is the Bogardus (1925) Social Distance Scale, a measure of prejudice, part of which is shown in Table 15.8. On the Social Distance Scale, acceptance of a group at any one distance (such as “To my street as neighbors”) implies acceptance of the group at greater distances; the greater the minimum acceptable social distance, the greater the prejudice. Behaviors can also be Guttman scaled if they represent a stepwise sequence, with one behavior always coming before the next; DeLamater and MacCorquodale (1979), for example, developed a Guttman scale of sexual experience. Guttman scaling is rarely used because few variables can be represented as a stepwise progression through a series of behaviors or beliefs.

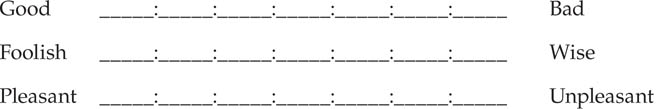

The semantic differential. The semantic differential (Osgood, Suci, & Tannenbaum, 1957) is a scale rather than a scaling technique, but is widely used because of its flexibility and so deserves discussion. In their research on the psychological meanings of words (as opposed to their dictionary definitions), Osgood et al. found that any concept could be described in terms of three dimensions: evaluation, representing the perceived goodness or badness of the concept; activity, represented whether the concept is perceived as active or passive; and potency, representing the perceived strength or weakness of the concept. A concept’s standing on each dimension is assessed by having respondents rate the concept on sets of bipolar adjective pairs such as good-bad, active-passive, and strong-weak. Because it represents one aspect of attitudes, evaluation tends to be the most commonly used rating dimension, and the scale takes the form of a set of segmented graphic rating scales; for example:

My voting in the forthcoming election is

(Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980, p. 55)

Each item is scored on a 7-point scale, usually ranging from +3 to -3, and respondents’ scale scores are the sums of their item scores. Notice that the items are balanced so that the positive adjective of each pair is on the right half the time; these items must therefore be reverse scored.

The semantic differential represents a ready-made scale that researchers can use to measure attitudes toward almost anything and so can bypass the item selection state of scale development. Its validity has been supported by more than 50 years of research. However, great care must be taken to ensure that the adjective pairs one chooses for scale items are relevant to the concept being assessed. For example, although foolish-wise is relevant to the evaluation of a person, behavior, or concept, it would be much less relevant to the evaluation of a thing, such as an automobile. Osgood et al. (1957) list a large variety of adjective pairs from which one can choose. Finally, Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) warn that many scales used in research are incorrectly called semantic differential scales. Although these scales use the semantic differential format, they consist of arbitrarily chosen adjective pairs rather than pairs that have been demonstrated to represent the rating dimension. Such scales are of unknown validity.

A response bias exists when a person responds to an item for reasons other than the response’s being a reflection of the construct or behavior being assessed by the content of the item. Response biases obscure a person’s true score on a measure and therefore represent a form of measurement error; better measures are less affected by response biases. Response biases can be categorized in two ways. Question-related biases are caused by the ways in which questions or response options are worded; person-related biases result from respondent characteristics.

The earlier section of this chapter that discussed question wording described some of the ways in which question stems can bias responses. This section describes four types of response bias that can result from item response options: scale ambiguity effects, category anchoring, estimation biases, and respondent interpretations of numerical scales.

Scale ambiguity. Problems with scale ambiguity can occur when using numerical or graphic rating scales to assess frequency or amount. Anchor labels such as “frequently” or “an extreme amount of” can have different meanings to different people. Consider the following hypothetical question:

How much beer did you drink last weekend?

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

A great amount |

Quite a bit |

A moderate amount |

A little |

None |

People evaluate frequency and amount relative to a personal standard (Newstead & Collis, 1987): To some people, one can of beer in a weekend might be a moderate amount and six cans of beer in a weekend a great amount; to another person, six cans might be moderate and one can a little. One possible solution to this problem is to use an ordered itemized scale, such as

How much beer did you drink last weekend?

_____ |

None |

_____ |

1 or 2 cans |

_____ |

3 to 6 cans |

_____ |

7 to 12 cans |

_____ |

12 to 24 cans |

_____ |

More than 24 cans |

Although using this response format can resolve some of the problems associated with the measurement of frequency and amount, it can lead to another form of response bias, category anchoring.

Category anchoring.Category anchoring occurs when respondents use the amounts provided in the response options as cues for what constitutes an appropriate response, based on the range of values on the scale. Schwarz (1999) distinguishes between two types of itemized scales. Low-range scales start at zero or a very low value and increase until reaching a “greater than” value, such as in a question that asks how many hours of television a person watches per day and provides response options that start at “Up to ½ hour” and increase in half-hour increments to more than 2½ hours.” High-range scales start at a higher value and increase until reaching a “greater than” value, such as in a television-watching question that provides response options that start at “Up to 2½ hours” and increases in half-hour increments to “More than 4½ hours.” Scales such as these are problematic because people tend to give lower responses with low-range scales and high responses with high-range scales. For example, Schwarz, Hippler, Deutsch, and Strack (1985) found that 30½ of respondents using the high-range scale just described reported watching more than 2½ hours of television per day, whereas none of the respondents using the low-range scale did. In comparison, 19% of people responding to an open-ended version of the question reported watching more than 2½ hours of television each day.

Another problem that can arise is that people see an option phrased in terms of “more than” a certain amount as representing an excessive amount and that endorsing it will make them look bad (Sudman & Bradburn, 1982). Finally, respondents may use the scale range to interpret the question stem, assuming that questions using low-range scales refer to events that happen rarely and that questions using low-range scales refer to events that happen frequently (Schwarz, 1999). For example, Schwarz, Strack, Müller, and Chassein (1988) found that people who were asked to report the frequency of irritating events assumed the question referred to major irritants when responding on low-range scales, whereas people responding on high-range scales assumed the question referred to minor irritants. Schwarz (1999) recommends using open-ended questions to assess frequency and amount as a solution for both of these problems.

Estimation biases. Open-ended questions asking for frequency and amount have their own problem. Unless the behavior being assessed is well represented in people’s memory, they will estimate how often something occurs rather than counting specific instances of the behavior. A problem can occur because memory decays over time, making long-term estimates less accurate than short-term estimates. It is therefore advisable to keep estimation periods as short as possible (Sudman et al., 1996). In addition, members of different groups may use different estimation techniques, leading to the appearance of group differences where none may exist. For example, men report a larger number of lifetime opposite-sex sexual partners than do women even though the numbers should be about the same (Brown & Sinclair, 1999). Brown and Sinclair found the difference resulted from men and women using different techniques to recall the number of sexual partners: Women generally thought back and counted the number of partners they had had whereas men tended to just make rough estimates. When this difference in recall method was controlled, Brown and Sinclair found that there was no sex difference in the reported number of partners.

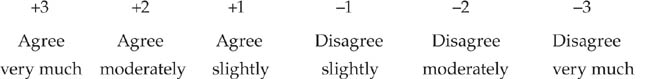

Respondent interpretation of numeric scales. As Box 15.4 shows, scale values can be either all positive numbers or a combination of positive and negative numbers. Just as respondents can use the range of itemized response categories to interpret the question, they can use the range of values on a numerical rating scale in the same way. For example, when people rated how successful they were in life, 34% responding on a -5 to +5 scale chose a value in the lower part of the scale range (-5 to 0), whereas only 13% of those responding on a 0 to 10 scale chose a value in the lower part of the scale range (0 to +5; Schwarz, 1999). Schwarz explains that

this difference reflects differential interpretations of the term “not at all successful.” When this label was combined with the numeric value “0,” respondents interpreted it to reflect the absence of outstanding achievements. However, when the same label was combined with the numeric value “-5,” and the scale offered “0” as the midpoint, they interpreted it to reflect the presence of explicit failures… In general, a format that ranges from negative to positive numbers conveys that the researcher has a bipolar dimension in mind, where the two poles refer to the presence of opposite attributes. In contrast, a format that uses only positive numbers conveys that the researcher has a unipolar dimension in mind, referring to different degrees of the same attribute. (p. 96)

Therefore, be certain of which meaning you want to convey when choosing a value range for a numerical rating scale.

Person-related response biases reflect individuals’ tendency to respond in a biased manner. There are five classes of person-related response biases: social desirability, acquiescence, extremity, halo, and leniency (Paulhus, 1991).

Social desirability.Social desirability response bias, the most thoroughly studied form of response bias, is a tendency to respond in a way that makes the respondent look good (socially desirable) to others (Tourangeau & Yan, 2007). Paulhus (1991) has identified two forms of social desirability response bias. Self-deceptive positivity is “an honest but overly positive self-presentation” (p. 21). That is, some people respond in ways that put them in a more positive light than is warranted by their true scores on the construct, but they do so unknowingly, believing the overly positive responses to be true. However, impression management is “self-presentation tailored to an audience”; that is, some people “purposely tailor their answers to create the most positive social image” (p. 21). Self-deceptive positivity is an aspect of personality and so is consistent across time and situations, whereas the type and amount of impression management that people engage in vary with the demands of the situation and the content of the measure. For example, people are more likely to try to “look good” during an interview for a job they really want than during an interview for a less desirable job. This distinction between the two forms of social desirability response bias has an important implication for measurement.

Paulhus (1991) notes that self-deceptive positivity is a component of some personality traits such as self-esteem and achievement motivation. Consequently, measures of such constructs should not be totally free of self-deceptive positivity; such a measure would not be fully representative of the construct. However, most measures should be free of impression management bias; the exceptions, of course, are measures of impression management or of constructs, such as self-monitoring (Snyder, 1986), that have an impression management component.

Because social desirability response bias is caused by motivation to make a good impression on others, the bias is reduced when such motivation is low. For example, people are more likely to exhibit social desirability response bias when making a good impression is important. Thus, Wilkerson, Nagao, and Martin (2003) found that people made more socially desirable responses when completing an employment screening survey than when completing a consumer survey. In addition, collecting data in ways that make respondents anonymous, such as by using anonymous questionnaires (Tourangeau & Yan, 2007) and not having an experimenter present when respondents are completing a questionnaire (Evans, Garcia, Garcia, & Baron, 2003), is effective in controlling social desirability response bias.

An Example of Acquiescence Response Bias

Question Form |

Percent Agreeing |

Individuals are more to blame than social conditions from crime and lawlessness in this country. |

59.5 |

Social conditions are more to blame than individuals from crime and lawlessness in this country. |

56.8 |

Note: From Schuman and Presser (1996).

Acquiescence. Acquiescence response bias is a general tendency to agree or disagree with statements, such as items on a self-report measure. People who show a tendency to agree are called “yea-sayers” and those who show a tendency to disagree are called “nay-sayers.” Although acquiescence response bias includes the tendency to disagrees, it is named after acquiescence, or agreement, because that aspect has received the most attention. For example, respondents to a survey answered one of two versions of a question about their perceptions of the cause of crime: whether it is caused by individual characteristics (such as personality) or by social conditions. As Table 15.9 shows, respondents tended to agree with the statements regardless of which causes was mentioned.

Acquiescence is a problem because it can make the meaning of scores on a measure ambiguous. For example, assume that a measure assesses anxiety by asking people whether they have experienced certain symptoms; respondents answer yes or no to each question. If someone gets a high score (that is, gives a large proportion of yes responses), does the score indicate a high level of anxiety or a yea-saying bias?

Acquiescence response bias is more likely to manifest itself when people lack the skill or motivation to think about answers, when a great deal of thought is required to answer a question, and when respondents are unsure about how to respond and so consistently agree or disagree as a way of resolving the uncertainty (Krosnick, 1999a). Writing questions that are clear and easy to answer will therefore help to reduce acquiescence response bias. Because acquiescence response bias has its strongest impact on dichotomous (yes/no or agree/disagree) questions, the use of other types of response formats will also help to alleviate its effects (Krosnick, 1999a).

The most common way of controlling for acquiescence response bias is through the use of a balanced measure. In a balanced measure, on half the items agreement leads to a higher score (called “positive items”) and on half the items disagreement leads to a higher score (“negative items”). For example, an interpersonal dominance scale could include items such as “I frequently try to get my way with other people” and “I frequently give in to other people.” Because agreement with one type of item leads to a higher score and agreement with the other type of item leads to a lower score, the effect of acquiescence on positive items will be balanced by its effect on the negative items. However, writing balanced questions can be difficult because questions intended to have opposite meanings may not be interpreted that way by respondents. Consider, for example, the questions shown in Table 15.10. Both questions assess respondents’ attitudes toward public speeches in favor of communism. They are also balanced in that the first question asks whether such speeches should be forbidden and the second asks whether they should be allowed. However, more people endorsed not forbidding the speeches than endorsed allowing the speeches.

An Illustration of the Difficulty of Writing Balanced Questions