Check participants’ understanding

The Post-experimental Interview

Using the Internet to Collect Data

The Validity of Web-Based Data

Advantages of Internet Research

Economy and ease of data collection

Access to research participants and other data

Potential for increased internal validity

Disadvantages of Internet Research

Limits on experimental stimuli and response modes

Lack of control over the data collection environment

Passive recruitment strategies

Monitoring participants for harm

Advantages of Using Archival Data

Limitations of Archival Research

Suggestions for Further Reading

Questions for Review and Discussion

Having selected a hypothesis to test and a research strategy to use in testing it, the researcher embarks on data collection. This is the most interesting and enjoyable phase of research, and often the most challenging, for it is here that researchers meet and interact with their research participants. In this chapter, we will briefly look at three aspects of this process: research participants, research procedures, and using the Internet to collect data. We then examine how archived data, which has been collected for purposes other than research, can be used to test hypotheses.

Some of the most important questions that researchers face are those dealing with research participants. This section examines the issues to consider in answering three of those questions: What population should I use? How should I sample from that population? How many participants will I need?

When we conduct research, we want our results to apply to a certain group of people. This group might be very broad, such as the entire population of the world, or it might be very narrow, such as the students attending a particular college or university, or the group can fall somewhere between these extremes, such as all people in the United States who possess a particular characteristic, such as depression. Regardless of how broadly or narrowly we define this group, it constitutes the target population for our research. Frequently, target populations for behavioral science research are defined in terms of hypothetical constructs, such as depression. In such cases, we must operationally define the target population in terms of some manifest variable. For example, we could operationally define depression in terms of psychiatric diagnosis. The people who meet our operational definition of the target population constitute the study population. For most research, the study population is so large that it is impossible to collect data from all of its members. We therefore select a research sample from the study population from whom we collect our data. Figure 16.1 shows the relationships among the target population, study population, and research sample.

The distinctions among the target population, study population, and research sample are important because the definition of the study population and the sampling process can affect the validity of the research. To the extent that the measure used to define the study population suffers from measurement error, the members of the study population will not correctly represent the target population, reducing the extent to which the results of the research will apply to the target population as a whole. For example, not everyone who is depressed is seen by a mental health professional and receives a diagnosis of depression, some diagnoses of depression might be erroneous, and some people who are depressed might receive some other diagnosis. Therefore, researchers must be careful to use only the most valid measures available when defining the study population.

Moving From Target Population to Research Sample.

The target population is the group of people to whom we want the results of our research to apply (such as depressed people), the study population consists of those members of the target population who fit a particular operational definition of the target population (such as having a psychiatric diagnosis of depression), and the research sample consists of the members of the study population who participate in the research.

In addition, to the extent that researchers’ operational definitions of the target population differ, their findings might differ, leading to apparent contradictions among the results of studies. Widom (1988), for example, has pointed out that the operational definition of abused child can vary greatly from study to study. One consequence of this variation is that estimates of the incidence of child abuse range from 500,000 cases per year to 2,300,000 cases per year. As Widom notes, one cannot expect convergence in findings among studies unless the studies use similar study populations. A third potential problem lies in the sampling procedure: The research sample might not be representative of the study population and therefore not representative of the target population. In Chapter 6, we discussed the issues surrounding the validity of measurement; now let’s turn to the question of sampling.

There are a large number of techniques that you can use to draw a research sample from a study population (Daniel, 2011). Most of these techniques can be described in terms of two dimensions: probability versus nonprobability sampling and simple versus stratified sampling. In probability sampling every member of the study population has a known probability of being selected for the research sample; in nonprobability sampling, the probability of a person’s being chosen is unknown. Simple sampling assumes that the method used to draw the research sample will provide a reasonable cross section of the study population in terms of personal characteristics, such as gender, race/ethnicity, age, and so forth, that are important to the research; stratified sampling structures the research sample so that the sample contains the same proportion of each important characteristic as the study population. In addition to the sampling techniques defined by these dimensions, researchers can use purposive sampling, in which they select participants based on characteristics important to the research, and snowball sampling, in which current participants recommend people they know as future participants. Let’s examine these techniques.

Probability sampling. The basic forms of probability sampling begin with a list of all the people in the study population, such as a roster of all the students attending a particular college or university. This list is called a sampling frame. The researchers then decide how many people they want to participate in the research (N) and select N names from the list. With simple random sampling, the researchers use a table of random numbers to do the selecting. Each name on the list is given a unique identification number, ranging, for example, from 001 to 999. Starting randomly in a table of random numbers, the researchers look at the last three digits of the first random number and select for the sample the person whose identification number matches those digits. They then go on to the next random number, selecting for the sample the person whose identification number matches its last three digits. Random number digits that are outside the range of identification numbers are skipped, as are those that match identification numbers already selected. The process continues until the desired number of participants is sampled. Each person in the sampling frame therefore has an equal probability—1/N—of being selected for the sample.

Quota Matrix for Sampling by Sex, Ethnicity, and Class.

Each person in the sampling frame is categorized by sex, ethnicity, and class and is assigned to the appropriate cell; researchers then sample randomly from each cell in proportion to its representation in the population.

For stratified random sampling, the sampling frame is arranged in terms of the variables to be used to structure the sample. Let’s say that the researchers want to ensure that the makeup of the research sample exactly reflects the makeup of the student body in terms of year in school (freshman, sophomore, and so on), gender, and ethnic group. The researchers draw up a quota matrix reflecting all possible combinations of these variables, such as the matrix shown in Figure 16.2. Each person in the sampling frame is categorized by these variables and assigned to the appropriate cell in the quota matrix; for example, all first-year Asian American women would be assigned to the upper left-hand cell in Figure 16.2. The researchers then sample randomly from each cell of the matrix, with each cell being sampled in proportion to its representation in the population. For example, if first-year Asian women constitute 1% of the study population and the desired sample size is 1,000, then 10 first-year Asian American women would be randomly selected for the sample.

Simple and stratified random sampling can be very difficult and time consuming to carry out, especially if the assignment of identification numbers and the selection of participants are done by hand rather than with the assistance of a computer. Even computerassisted random sampling can be laborious if the list comprising the sampling frame is not already available in a database and must be entered manually. A simple alternative to random sampling is systematic sampling. With systematic sampling, you start with a sampling frame and select every nth name, where n equals the proportion of the frame that you want to sample. For example, for a 10% sample, you would go down the list selecting every 10th name. Systematic sampling can also be stratified; by selecting every nth man and every nth woman results in a sample that is stratified by gender, for example. A danger in systematic sampling is a problem known as periodicity: The sampling frame is arranged so that some characteristic appears with the same pattern as the sampling interval, resulting in a biased sample. For example,

in a housing development or apartment house every eighth dwelling unit may be a corner unit. If it is somewhat larger than the others its occupants can be expected to differ as well. If the sampling [interval] also happens to be [eight], one could obtain a sample with either all corner units or no corner units depending on the [starting point]. (Blalock, 1979, p. 559)

Fortunately, periodicity is rarely found in practice, but you should still carefully examine lists to be used for systematic sampling to guard against the problem.

A major problem inherent in random and systematic sampling is that you must have a list of the entire study population to use as a sampling frame. Therefore, these sampling approaches can normally be used only with relatively small study populations, such as the students enrolled in a particular college or university. But what if you define your study population as all the college and university students in the United States? There is no comprehensive listing of this population. The answer to this problem is cluster sampling. With cluster sampling, you first identify groups or clusters of people who meet the definition of the study population; in our example, the clusters would be colleges and universities. You then take a random sample of the clusters and use all members of the sampled clusters as research participants. When the clusters themselves are large, sampling can also be conducted within clusters. When membership lists are available, random or systematic sampling can be used. Otherwise, you would use multistage cluster sampling, in which clusters are sampled within clusters. For example, for a face-to-face survey in a geographic area, census tracts can form the initial clusters; census blocks are sampled within tracts, houses or apartment buildings within blocks, apartments within apartment buildings, and people within apartments or houses. Cluster samples can also be stratified; in the college and university example, you could stratify by public versus private institution and by size. Census tracts or blocks could be stratified by their ethnic composition as reflected in census data.

Probability sampling is the ideal form of sampling because if done carefully it will provide a pool of potential research participants whose characteristics are near-perfect reflections of those of the study population. Probability sampling can therefore provide a sample that is highly representative of the population. This high degree of representativeness is only potential, however, because it may be impossible to contact some members of the potential participant pool and others may refuse to participate when contacted. To the extent that refusals and other causes of “lost” potential participants are related to participant characteristics, the people who actually participate in the research will not be representative of the population. For example, Doob and Macdonald (1979) identified highand low-crime city and suburban areas in and around Toronto. A door-to-door survey was conducted of randomly selected adults from randomly selected households in each area. Despite these stringently random sample-construction procedures, 70% of the respondents to the survey were women. It is therefore important to compare the characteristics of the people who take part in the research to the characteristics of the population that was sampled using whatever data are available—usually demographic information—to assess the degree to which the people who took part in the research represent the population.

Even when you can be fairly confident of obtaining a representative group of participants, probability sampling can be very difficult to carry out unless the study population is relatively small, such as the membership of an organization. Data collection based on probability sampling can also be very expensive if a geographically diverse population, such as that of a nation, is being sampled. In addition, if members of the sample do not live near the researcher, the research must be carried to them, rather than having them come to the researcher. Consequently, the research must often be based on questionnaires, limiting the forms that experimental manipulations can take and limiting measurement to self-reports.

Nonprobability Sampling. Probability sampling is used infrequently in behavioral science research, partly because of the costs involved and partly because of the limitations it places on experimental manipulations and the types of measures that can be used. Consequently, researchers are more likely to use nonprobability or convenience samples. As the latter term implies, nonprobability samples consist of people from whom the researcher finds it convenient to collect data. For example, researchers might select depressed people as their target population for a study and define the study population as people who score above a certain point on a self-report depression inventory. However, rather than trying to draw a probability sample from that population, the researchers administer the depression inventory to students at the university where they teach and use those who score above the cutoff as the research sample. University students are selected as research participants not because they are necessarily representative of the target population, but because the researchers find it easy to collect data from them. When researchers use essentially anyone who happens to be convenient as research participants, they are said to have conducted haphazard sampling. Haphazard samples can also be stratified using a quota matrix such as that shown in Figure 16.2, in which case they are known as quota samples.

Convenience samples are not restricted to college students. Marketing researchers often use “mall intercept interviews,” recruiting as participants people walking in shopping malls. Researchers also sometimes ask people in shopping malls, parks, and other public places to answer questionnaires, or they recruit participants through interest groups found on the World Wide Web.

Convenience samples are generally easy to acquire and inexpensive for data collection. As noted in Chapter 3, college and university students are frequently drafted as research participants to form convenience samples. Members of convenience samples can usually come to the researcher’s laboratory, enabling the researcher to use complex experimental manipulations and behavioral and physiological measures. However, the researcher has no way of knowing the degree to which the members of a convenience sample are representative of the target population. The more the characteristics of the members of the sample differ from those of the members of the target population, the less likely the results of the research are to apply to the target population. As you will recall from Chapter 8, there are very important validity issues related to convenience sampling, and this method of selecting research participants is highly controversial.

Purposive Sampling. In purposive sampling researchers use their judgment to select the membership of the sample based on the research goals. Purposive sampling is frequently used in case study research, in which researchers often want to study typical or critical cases (see Chapter 13). A typical case, as the term implies, is one that the researcher believes is representative of the average case. For example, a researcher might choose a school for a case study because the demographic characteristics of its students and faculty appear to be representative of most of the schools in the district. A critical case is one that has one or more characteristics of special interest to the researcher. For example, a researcher might choose a school as the test case in a comparative case study because it represents a particular level of an independent variable, such as funding; other schools with different funding levels could be chosen as control or comparison cases. Purposive sampling can be further used to select individuals within the school as sources of data by targeting for interview “key informants” who have special knowledge that is of interest to the researcher.

Snowball Sampling. The final form of sampling is known as snowball sampling. In this procedure, people who are initially selected for a sample using convenience or purposive sampling nominate acquaintances whom they think might be willing to participate in the research. The nominees who agree to participate are then asked to nominate other potential participants. The sample size therefore grows like a rolling snowball, hence its name. This procedure is frequently used in developmental research: Once a group of parents whose children are at the age required for the research has been identified, those parents can recommend other people who have children of the same age as research participants and might even encourage friends and relatives to participate. Snowball sampling is also used to construct samples of hard-to-reach populations whose members might otherwise be unidentifiable, such as illegal drug users.

In addition to deciding on how to sample research participants, the researcher must also decide how many people to sample. The question of sample size is closely related to the question of statistical power, so we must begin there.

Statistical Power. You will recall that the p value associated with the outcome of a statistical test, such as the t test, represents the probability of concluding that the independent variable had an effect on the dependent when, in fact, it did not. Statistical testing has traditionally focused on the probability of deciding that the independent variable had a real effect on the dependent variable when, in fact, the effect found in the sample was due to chance. As shown in the top part of Table 16.1, the Type I error rate, or alpha level, usually set at 05, represents the probability of making this kind of error. If the statistical test indicates no effect of the independent variable—that is, is p greater than .05—there is also a probability that the independent variable would have had an effect in the population, but, due to error, that effect was not found in the research sample. As shown in the bottom part of Table 16.1, the error caused by incorrectly concluding that the independent variable had no effect is called a Type II error; the probability of a Type II error is represented by beta, which, like alpha, can range from 0 to 1. Statistical power, represented by 1 – beta, is the probability of not making a Type II error. That is, if a statistical test has insufficient power, it increases the chances of erroneously concluding that the independent variable had no effect on the dependent variable. You therefore must have high statistical power to avoid false negative results.

The power of a statistical test depends on several factors, including the alpha level chosen for the test, the size of the effect that the independent variable has on the dependent variable, and the size of the research sample. This discussion will assume that alpha equals .05 and that an independent variable can have a small, or medium, or large effect. The operational definition of effect size depends on the statistical test, but we will consider a small effect to be equivalent to a correlation of .10 between the independent and dependent variables, a medium effect to be equivalent to a correlation of .30, and a large effect to be equivalent to a correlation of .50 (Cohen, 1988). Unfortunately, much behavioral science research has inadequate statistical power. For example, Rossi (1990) found that research published in four major psychology journals in 1982 had an average statistical power of only .17 for small effects, .57 for medium effects, and .83 for large effects. This means that if an independent variable has only a small effect on a dependent variable, researchers are not detecting that effect 83% of the time, and when an independent variable has a medium effect, researchers are not detecting it 43% of the time.

Type I and Type II Errors

A Type I error is erroneously concluding that an independent variable had an effect; a Type 11 error is erroneously concluding that an independent variable did not have an effect. |

||

Real Effect of the Independent Variable |

||

|

Relationship |

No Relationship |

Conclusion Drawn from Data |

|

|

Relationship |

Correct decision |

Type I Error (probability = alpha) |

No Relationship |

Type II Error (probability = beta) |

Correct decision |

Determining sample size. One way for researchers to improve the likelihood of detecting the effect of an independent variable is by conducting high-power research; one way of increasing power is to ensure an adequate sample size. To determine the appropriate sample size, you need the answers to four questions. First, what effect size are you trying to detect with your research? This target effect size is the critical effect size (Kraemer & Thiemann, 1987). There are several approaches to answering this question. One approach is to decide on the smallest effect you consider important to the theory or application your research is testing. For example, if you set your critical effect size at r = .25 using this approach, you are saying that any correlation smaller than .25 is equivalent to a correlation of zero for the purpose of answering your research question. Minimum critical effect sizes can be important in applied research because an intervention (that is, an independent variable) that doesn’t have a certain minimum impact might not be cost effective to implement. A second approach to deciding on the critical effect size is to use the average effect size found in previous research using your independent and dependent variables. Researchers who use a form of literature reviewing discussed in Chapter 19, called a meta-analysis, calculate mean effect sizes for bodies of research. For example, Richard, Bond, and Stokes-Zoota (2003) examined results of 322 meta-analyses on social psychological topics; results showed that effect sizes in social psychological research vary by topic, but that 3% had an r = .10 or less, 41% had an r between .11 and .29, 24% had an r between .30 and .49, and 5% had an r = .50 or greater. In Appendix B of their paper, Richard et al. provide effects sizes for a large number of social psychological topics that can be used to estimate the statistical power needed to conduct research in those areas. If no meta-analysis has been published, you could conduct one yourself. Finally, lacking any theoretical, applied, or empirical basis for setting a critical effect size, you could simply use a medium effect size and probably be all right. Lipsey (1989) found that the average effect size found across 186 meta-analyses of research on mental health and educational interventions fell right in the middle of the medium range.

The second question to ask is, What alpha level will I use? The smaller the alpha (for example, .01 versus .05), the lower the statistical power will be and the larger the sample you will need to achieve a given level of statistical power. By convention, most researchers set alpha at .05. The third question is, Will I use a one-tailed or two-tailed statistical test? A one-tailed test looks for either a positive relationship between the independent and dependent variables or a negative relationship, but not for both simultaneously. A two-tailed test looks for both. Use of a one-or two-tailed test depends on whether you have a directional or nondirectional hypothesis (see Chapter 5). A two-tailed test has less power than a one-tailed test, and so requires a larger sample size to achieve a given level of power. The final question is, What level of power do I want? Generally speaking, the higher the power, the better. One would certainly want power to exceed .50, giving a better than 50% chance of detecting an effect; Cohen (1992) suggests a level of .80.

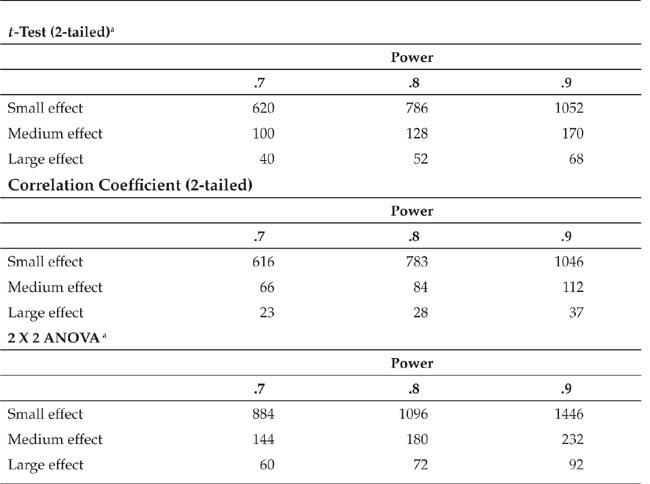

Sample Sizes for Three Levels of Statistical Power for Detecting Small, Medium, and Large Effects of an Independent Variable for Alpha = .05

Note: Small effect is equivalent to a correlation of .10, medium effect to a correlation of .30, and large effect to a correlation of .50. Adapted from J. Cohen, 1988.

aNumbers indicate total sample size (not number per group) and assume equal-size groups.

To give you an idea about the relationship between sample size and statistical power, Table 16.2 gives the minimum total sample sizes needed to detect small, medium, and large effects at three levels of power. The table assumes that alpha equals .05, that two-tailed tests are used for t and r (ANOVA uses only a one-tailed test), and that there are equal group sizes for the t-test and ANOVA. Notice that a reasonable level of statistical power for a small effect requires an extremely large sample. Therefore, if only a small number of potential participants are available, it might not be very useful to test independent variables that are likely to have small effects. The sample sizes in Table 16.2 are taken from a book by Cohen (1988) that contains sample size tables for a variety of statistical tests, a wide range of critical effect sizes, and a wide range of power levels (see also Cohen, 1992).

A sample of a particular size represents a tradeoff between ease of data collection (smaller samples are easier to deal with in terms of time and money than are larger samples) and protection against making a Type II error (larger samples provide more protection than do smaller samples). Kraemer and Thiemann (1987) summarized these tradeoffs in terms of what they called six “facts of life”:

• |

The more stringent the significance level, the greater the necessary sample size. More subjects are needed for a 1 percent level test than for a 5 percent level test. |

Two-tailed tests require larger sample sizes than one-tailed tests. Assessing two directions at the same time requires a greater investment. | |

• |

The smaller the critical effect size, the larger the necessary sample size. Subtle effects require greater efforts. |

• |

The larger the power required, the larger the necessary sample size. Greater protection from failure requires greater effort. |

• |

The smaller the sample size, the smaller the power, i.e., the greater the chance of failure.… |

• |

If one proposes to [use] a sample size of 20 or fewer subjects, one must be willing to take a high risk of failure, or be operating in an area in which the critical effect size is large indeed. (p. 27) |

In previous chapters, we discussed several aspects of the mechanics of research: measuring variables (Chapter 6), controlling threats to internal validity (Chapter 7) and external validity (Chapter 8), manipulating variables (Chapter 9), and issues in conducting research in natural settings (Chapter 10). In this section, we look at some additional aspects of carrying out a study: the characteristics of effective research settings, effective instructions for participants, “debugging” the research procedures, running a data collection session, the post-experimental interview, and supervising research assistants.

An effective research setting is one that contributes to the validity of the data collected in it. In Chapter 10, we discussed some characteristics of an effective setting for field research; let us look now at four factors that contribute to the effectiveness of any research setting, be it a laboratory or field setting: coherence, simplicity, psychological involvement, and consistency (Aronson, Ellsworth, Carlsmith, & Gonzales, 1990).

Coherence. A coherent research setting is one that participants experience as a smooth, logical flow of events, all of which are focused on the purpose of the research. Participants must understand how each event they experience, such as performing a task or filling out a questionnaire, is related to the purpose of the research as it has been explained to them. We say, “as it has been explained to them,” because if the research procedures involve deception, the events must appear to be related to the cover story used to explain the research to the participants. A lack of understanding or feelings of ambiguity about their experience will raise participants’ levels of anxiety and start them wondering about what is happening to them. These feelings and thoughts will distract participants from what the researcher wants them to think, feel, or do, and so threaten the validity of their responses. For the same reason, the researcher should keep participants’ attention focused on the task at hand, such as by giving a well-focused explanation of the research task, and not bring up side issues such as by saying something along the lines of “Oh, by the way, we’re also interested in how this relates to X.” If X is important, it should be fully integrated into the explanation; if unimportant, it should not be mentioned to the participants.

The exception to maintaining a smooth flow of events throughout a data collection session is when a planned disruption is part of the research. Darley and Latané (1968), for example, investigated the variables related to people’s responses to emergencies by arranging for a simulated emergency to interrupt what participants thought was an experiment on some other topic. In this case, the disruption was intended to ensure the participants’ complete psychological involvement in the research, a characteristic of effective research settings that will be discussed shortly.

Simplicity. The apocryphal philosopher Murphy is credited with formulating one of life’s most basic laws: “Anything that can possibly go wrong, will go wrong.” A corollary to that law is that the more complex something is, the more there is that can, and so will, go wrong. Consequently, it is wise to keep research settings and the events that take place in them as simple as possible. For example, don’t use complicated electronic or mechanical apparatus for data collection when more simple means are available—it might make research participants nervous, and equipment failure means loss of data.

Don’t use complex social manipulations involving several confederates when simple alternatives are possible—if one confederate blows his or her lines or fails to show up for a research session, those data are lost. In addition, a complex set of events or a complex explanation of the study is likely to be confusing, and therefore distracting, to research participants. Aronson et al. (1990) propose a rule for testing the simplicity of a research setting: “Pretest the experimental rationale and procedure on one’s friends; if they react with blank stares, it is unlikely that a subject will be able to follow it, and some revision is in order” (p. 186).

Psychological Involvement. An effective research setting arouses and engages participants’ interest in what is happening to them and what they are doing; it gets them fully involved psychologically. Lack of involvement leads participants into distraction and boredom, resulting in low motivation and lack of validity in response to the independent variable. One way to make research involving is to make it realistic; this is one reason for using field settings even for experimental research. However, Aronson and Carlsmith (1968) distinguished between two forms of realism in research. A research setting has experimental realism if it leads participants to become psychologically involved in what is happening, if it forces them to take things seriously, and if it has an impact on them. A research setting has mundane realism if the events occurring in the setting are likely to occur in some natural setting. As we discussed in Chapter 8, many researchers consider mundane realism important to the generalizability of research results. However, Aronson and Carlsmith do not consider mundane realism sufficient for the creation of an effective research setting. As they see it, “The mere fact that an event is similar to events that occur in the real world does not endow it with importance. Many events that occur in the real world are boring and unimportant. Thus it is possible to put a subject to sleep if an event is high on mundane realism but remains low on experimental realism” (p. 22).

Mundane and experimental realism are independent concepts: A research situation might be high on both, low on both, or high on one but low on the other. For example, Milgram’s (1974) obedience experiments, described in Chapter 3, were low on mundane realism (people are almost never asked to give severe electrical shocks to other people) but high on experimental realism (participants’ psychological involvement in the research setting was shown by their stressful reactions to giving the shocks). Conversely, MacQuarrie, Tucker, Burns, and Hartman (2002) manipulated the ratio of known to unknown words presented on flashcards and assessed whether children’s retention for new vocabulary improved when a higher ratio of known words was included in the flashcard set. This is undoubtedly a realistic and mundane task, but one not likely to capture the children’s interest to a great degree. In contrast, consider Murray’s (1963) research in which college students took part in a discussion with a confederate posing as another student who challenged the participants to defend their cherished values and personal philosophies of life. Such an experience is both highly involving and likely to happen either in class or in discussions with other students, and it is therefore high on both experimental and mundane realism.

You have probably noticed that achieving a high degree of experimental realism can be at odds with the principle of simplicity. Milgram’s (1974) research, for example, used both a complex scenario involving a researcher, the participant, one or more confederates, and a fair amount of complex apparatus—a phony shock generator, a signaling system, tape recorders, hidden data recorders, and, in some experiments, an intercom system. Here, as in other aspects of research design, the researcher must decide on the appropriate tradeoff between two at least somewhat incompatible but desirable characteristics: Is the degree of experimental realism gained by an increase in complexity worth the increased likelihood of things going wrong and the attendant loss of data? One way to assess the tradeoff is by conducting detailed rehearsals and pilot studies, discussed later in this section.

Although experimental realism and participant involvement are important, Aronson et al. (1990) point out that participants should not be so involved in the situation that they overlook the independent variable: “For example, if the experimenter wants to arouse aggression in a [participant] by having an obnoxious confederate deliver an inordinate amount of distracting stimulation while the [participant] is working on a task, the task [should not be] so exciting and absorbing that the [participant] will … disregard the noxious stimuli” (p. 187).

Consistency. Finally, a good research setting provides a consistent experience for each participant. Everyone has the same experience up to the point at which the independent variable is manipulated so that everyone is in the same psychological state before being introduced to their condition of the independent variable. This consistency of pre-manipulation experience minimizes situational variables as possible sources of extraneous variance in the dependent variable, making the effect of the independent variable easier to detect. Each participant must also have the same experience within their condition of the independent variable, thereby ensuring the reliability of the manipulation, which contributes to its construct validity. Unreliable manipulations, like unreliable measures, contain a high degree of random error and so are less likely to be valid representations of the hypothetical construct that the experimenter is trying to manipulate. Consistency can be achieved by developing detailed scripts for the procedures in each condition of the independent variable, carefully rehearsing experimenters and confederates, and by monitoring their performance during data collection (see Chapter 9). As noted in Chapter 10, field research trades off some of this consistency for an increase in naturalism.

Instructions to research participants are an essential component of research. Instructions orient participants to what will happen during the data collection session, tell them how to perform research tasks and how to complete self-report measures, and can be used to manipulate the independent variable. To meet these goals effectively, instructions must be clear, must get and hold participants’ attention, and must be accompanied by procedures that check participants’ understanding of the instructions.

Be Clear. When writing instructions, whether they are to be delivered orally or in writing, strive to be as clear, complete, and simple as possible. One way to increase participants’ understanding of instructions is through repetition. Butler (1986; Butler & Jones, 1986) found that repetition of instructions dramatically improved research participants’ ability to correctly perform a variety of research tasks. A single presentation of instructions resulted in an average error rate of 55%, two presentations reduced the error rate to 26%, and three reduced it to 10%; further repetition resulted in no increase in performance accuracy. Examples also help. Butler and Jones (1986), using a difficult task, found that one presentation of instructions without an example resulted in an 80% error rate, whereas the error rate was 40% when an example was included. The clarity of instructions can be validated with Aronson et al.’s (1990) “blank stare” test: Read them to friends; if you get blank stares in return, you need to revise the instructions.

Get Participants’ Attention. Getting and holding participants’ attention involves the same behaviors as getting and holding attention in any conversation: maintaining eye contact, speaking clearly, emphatically, and fluently, and speaking with an appropriate degree of animation. In other words, talk to the participants, don’t merely read to them from a script in a monotone, and don’t mumble or stumble over unfamiliar words and phrases. The more familiar you are with the instructions, the easier it is to deliver them in a natural, conversational manner. Therefore, always rehearse instructions until you are thoroughly familiar with them and can deliver them clearly.

Check Participants’ Understanding. Don’t assume that participants understand even the best-designed and best-presented instructions; always check to ensure their understanding. At a minimum, solicit questions. However, do not say, “Do you have any questions?” or worse, “You don’t have any questions, do you?” Such inquiries invite a “No” response. It’s better to ask, “What questions do you have?” which implies that it is reasonable to have questions and that you expect them. When the instructions are complex, it is useful for the experimenter to ask questions that check the participants’ understanding or to demonstrate their understanding by performing the research task. Probes of this nature should focus on aspects of the instructions that are likely to be particularly troublesome to participants. These problem areas can be identified during pilot testing, to be discussed shortly.

“Debugging” is a term coined by computer programmers for the process of finding errors or “bugs” in programs. The term has been borrowed by researchers to refer to the process of finding problems in research procedures. Debugging is accomplished in three steps: the research proposal, rehearsal, and pilot studies.

The research Proposal. The research proposal is a detailed discussion of the background and hypotheses for a piece of research and a detailed description of the procedures to be used in testing the hypotheses (see Chapter 5). The debugging process starts by having colleagues read the proposal with an eye to finding any problems that the researcher overlooked. Colleagues might note problems in the derivation of hypotheses, they might be able to suggest important extraneous variables the researcher overlooked, they might know of better operational definitions, or they might be aware of problems with the materials or apparatus that the researcher intends to use. Colleagues’ suggestions on these and other potential problem areas can be used to fix the problems before time and effort are expended in setting up the research.

Rehearsal. Once the research procedure looks good on paper, it’s time to try it out in practice, using rehearsals or “dry runs” that do not include research participants. It can be useful to think of data collection as a stage play with the research procedure as the script. As with a theatrical rehearsal, the research rehearsal should proceed as if it were the real thing, with the researcher giving instructions out loud, walking around the room distributing questionnaires, operating equipment, and so forth, and with confederates playing their roles, all as specified in the research procedures. Rehearsals provide the researcher with practice so that data collection sessions proceed smoothly and with the opportunity to find procedural problems not apparent in the research proposal. For example, as a graduate student, one of us once worked as an experimenter on a project that required the operation of two pieces of equipment simultaneously. This was not a problem in itself, because it was easy to operate each device with one hand. However, when rehearsing the procedure, it turned out that the laboratory was arranged (from a previous research project) so that the two pieces of equipment were 10 feet apart! Needless to say, the experiment was put on hold until the lab was rearranged. Rehearsals should continue until the entire procedure runs smoothly without any “blown lines,” forgotten “stage business,” overlooked “props,” or other disruptions.

Pilot Studies. A pilot study is a preliminary piece of research conducted with a sample of research participants drawn from the study population. Pilot studies can be used for several purposes. First, they can consist of observational or correlational research conducted to determine if it would be worth the time and effort to conduct an experiment. For example, recall Middlemist, Knowles, and Matter’s (1976) study of the effect of invasions of personal space in men’s rooms on anxiety, described in Chapter 3. Before they designed their rather complex experiment involving both a confederate and a hidden observer, they conducted an observational study to determine if naturally occurring invasions of personal space were correlated with latency of urination. Because the correlational data were consistent with their hypothesis, they went ahead with an experimental test of the causal role of personal space invasion. The pilot study also gave the researchers the opportunity to interview participants to determine the participants’ feelings about being observed under such circumstances.

Second, pilot studies can be conducted to test the validity of experimental manipulations. The dependent variable in such pilot studies is a measure of the hypothetical construct that the researchers want their manipulation to affect. Recall, for example, Seligman, Finegan, Hazlewood, and Wilkinson’s (1985) pizza delivery study described in Chapter 10. They intended their explanations of why the delivery driver was early or late to manipulate customers’ perceptions of whether the early or late delivery was due to the actions of the driver or due to situational factors. They tested the effectiveness of the manipulation by approaching people in their university’s library and asking them to rate the explanations as to whether they appeared to reflect characteristics of the delivery driver or of the situation. Because this pilot manipulation check supported the validity of their procedure, they used it in their study.

Finally, pilot studies are conducted as a final test of research procedures prior to beginning data collection. Such pilot studies are useful because the researcher can solicit the participants’ cooperation in the process by telling them at the outset that they are assisting in a test of the research procedures and asking them to note any aspects of the procedures they find difficult to understand and any tasks they find difficult to perform. The researcher can also interrupt the course of events at various points to collect information from participants. For example, the researcher can give pilot participants the instructions to be used in the study and then ask whether they understand what they are to do or if they expect to have any difficulty in carrying out the instructions. Pilot studies can also help to detect any demand characteristics present in the research setting or procedures—aspects of the setting or procedures that “push” participants to respond, or to avoid responding, in certain ways. For example, Aronson et al. (1990) describe a pilot study for an experiment in which college students were asked to look at photographs of three men and pick out the one who was Jewish:

[Participants] became upset, arguing that it was impossible to recognize Jews on the basis of appearance.… On the basis of the information gained from these pilot [participants], the experimenters changed the test so that [the participants] were asked to pick out schizophrenics rather than Jews, and from then on the experiment ran smoothly. (p. 234)

When such problems arise in a pilot study, ask the participants for suggestions on how to improve the clarity of the instructions or the nature of a problematic task. You can also develop probes to test participants’ understanding of instructions for problem areas that cannot be changed.

Pilot studies also give the researcher an opportunity to determine whether the participants are interpreting things as intended. For example, does a questionnaire item have the same meaning to them as to the researcher? Ross and Allgeier (1996), for example, found that male college students interpreted some items on a frequently used sexual experiences questionnaire to have as many as six possible meanings each, some of which were contradictory. For instance, 37% of the participants interpreted the question “Have you ever had a women misinterpret the level of sexual intimacy you desired?” to mean the woman overestimated the man’s desired level of sexual contact whereas 25% interpreted it to mean the woman underestimated the desired level of contact.

Participants might also interpret the procedures used to manipulate the independent variable in a different way from that intended by the researcher, resulting in an invalid manipulation. For example, Dane (1990) tells of a study he was conducting in which he wanted to see if physiological arousal affected men’s perceptions of women’s attractiveness. He manipulated arousal by sitting either 3 inches from the participants in the high-arousal condition or across the room from participants in the low-arousal condition. He got what seemed to be very strange results that made it appear that participants in the high-arousal condition were not paying attention to the photographs they were supposed to be rating. Therefore, as Dane (1990) tells the story,

I called some of [the participants], interviewed them, and discovered that indeed many of them were not concentrating on the women in the photograph. It seems that my results were caused by the participants’ beliefs about what was being studied. Most of the participants in the high arousal condition [were uncomfortable] because I was sitting very close to them.… They admitted to completing the ratings as quickly as they could so that they could get out of the room. (p. 210)

Pilot studies also let researchers know how much time is required for the research tasks and the data collection session as a whole. Researchers might find, for example, that a task takes participants more time to complete than was anticipated, so the research session must be lengthened. To fit a research session into their schedules, participants must be informed well in advance of the total time they will be asked to donate. Total time is also important when participants come from subject pools. In such circumstances, students are often given credit for research participation in terms of the amount of time they contribute; researchers have an obligation to these students to provide the correct amount of credit.

The last few sessions of the final pilot study conducted should function as “dress rehearsals” for the data collection sessions. As in a theatrical dress rehearsal, these sessions should be conducted without interruption except to answer participants’ questions. These complete run-throughs allow a final smoothing of the rough edges of the procedures. Dress rehearsals should continue until the experimenter and any confederates can play their roles with minimal error.

A common question that arises concerning pilot studies is that of the number of research participants to include. There is no absolute answer to this question; it depends on the goal of a particular study. If you are doing preliminary observational work, as Middlemist et al. (1976) did, or checking the validity of a manipulation, as Seligman et al. (1985) did, you want to have enough data to provide enough statistical power to be able to have confidence in your results. The number of participants therefore depends on the minimum effect size that you consider important for your goal. When collecting information from participants to improve procedures, you should probably keep collecting data and modifying procedures until participant comments indicate that no additional substantial improvements can be made.

In planning a research project, be sure to budget sufficient time for pilot studies. Note the use of the plural—studies, not just one study. Piloting is an iterative process: A problem is identified, a fix is implemented, and then the new procedure must be tested. A number of iterations of the process might be required before the entire procedure runs smoothly.

In this section, we want to remind you about some aspects of conducting a data collection session. First, be sure to dress neatly. A suit or dress is not required, but at the other extreme—a dirty sweatshirt and tattered jeans hardly presents a professional appearance. People do judge you by the clothes you wear, and if your attire does not convey to participants the impression that you consider the research to be serious business, they will not take it seriously either. Next, be sure to arrive at the research site well ahead of time. Remember many participants will be early and may be confused if the experimenter is not there to greet them. Also, arrive completely prepared to conduct the research. If you are using questionnaires, check the number on hand sufficiently far in advance (several days, if necessary) to ensure that you have enough available. Don’t forget to bring enough pencils and, if they are used, answer sheets. If you are collecting data on computers, have all machines up and running before the participants arrive. If you are using any apparatus, such as an EEG, get to the research site early enough to thoroughly test the equipment and to calibrate it, and take care of any other routine maintenance before the participants arrive.

Finally, be sure to treat your research participants politely, unless the experimental manipulation calls for something else. Remember, these people are donating their time to help you with your research. Greet all your participants, answer their questions completely and courteously (even questions about things you’ve already covered several times), and thank them when their participation ends. Never let a data collection session run over the allotted time; your participants probably have other obligations. If you can’t make a scheduled session, notify your participants as far in advance as possible if you have their phone numbers or electronic mail addresses. Otherwise, arrange to have someone meet them at the research site and explain the problem. At a minimum, have someone leave a polite note. If participants were to receive some form of credit, be sure to inform them how to obtain it and promptly submit any paperwork you need to ensure they receive that credit. In short, treat your research participants as you would like to be treated in the same circumstances.

The purpose of a post-experimental interview is to uncover any ethical or methodological problems with the research and to educate the participant about the purpose of the study. If your study has the potential for methodological or ethical problems, at the close of a data collection session, you should conduct a post-experimental interview with the participants. This interview is also appropriate for those studies that have complex procedures or involve deception. This interview has four functions: ethical, educational, methodological, and discovery. This section will examine each of these functions and then outline a procedure for the interview.

The ethical Function. As discussed in Chapter 3, the researcher has a number of ethical obligations to research participants after data collection. Two of these obligations are fulfilled as part of the post-experimental interview. First, the researcher must alleviate any adverse effects of the research, such as by reassuring participants whose self-esteem may have been threatened by the research procedures. Second, if deception was used, the researcher must debrief the participants, explaining the nature of the deception and the reasons for it. You might want to go back and review the section in Chapter 3 on debriefing to refresh your memory on these topics.

The educational Function. As noted in Chapter 3, the researchers’ post-research ethical obligations include educating research participants about the nature of research in general and of the research in which they participated in particular. Because this educational benefit is frequently the only direct benefit received by participants drafted from subject pools, researchers have a special obligation to those participants. Sieber (1992) suggests that the educational function of the post-experimental interview include

a brief, nontechnical presentation on (a) the purpose of the study, (b) the relation of the purpose to the condition(s) in which [they] participated, (c) what is known about the problem and what hypotheses are being tested, (d) the dependent and independent variables, and (e) why the study is of theoretical or practical importance. At this time, [participants] also might be given a one-or two-page description of the topic and the research, expanding on what they had already been told. (pp. 40–41)

The researchers should also solicit questions about the explanation, make themselves available to participants who want to discuss the research further, and provide the name and phone number of someone to call if they have questions later. Not all research participants, especially those who take part in studies using group-administered questionnaires, will be motivated to stay and listen to an oral presentation about the research. In this and other cases of minimal-risk research, a handout might be sufficient to meet the educational obligation.

Although researchers generally believe that they present good debriefings, participants frequently complain that debriefings are inadequate. They say that the debriefings they have experienced were too brief, difficult to understand, used terms that were unfamiliar to them, and did not put the research into a context understandable to them, such as the potential applications of the research results (Brody, Gluck, & Aragon, 2000). Brody et al. also found that participants reported that the researchers treated the debriefing process as a burdensome obligation rather than as an opportunity to educate participants and that the researchers appeared to be uninterested in answering questions. Therefore, regardless of whether the debriefing is oral or written, pretest it with colleagues and pilot study participants to ensure that it is clear and complete, present it in a professional manner, and be sure to encourage participants to ask questions.

The methodological Function. The post-experimental interview can be used to administer manipulation checks and to assess the degree to which participants were affected by demand characteristics or misperceptions of the research situation or were suspicious about any deception that was used. Although pilot studies can provide researchers with information about the effectiveness of their manipulations in general, manipulation checks conducted after a research session can assess whether the manipulation was effective for individual participants. In Chapter 7, we discussed demand characteristics and noted that they can reduce the validity of participants’ responses. Misperceptions of the purpose of the research can also reduce response validity. To the extent that participants are suspicious of deception or otherwise believe that something is “not right” about the research situation, the manipulation of the independent variable is invalid.

The post-experimental interview can therefore help the researcher sort out effective research sessions—in which everything went as intended—from ineffective sessions in which something went wrong. What should you do about data from “spoiled” sessions? If the post-experimental interview suggests that the manipulation of the independent variable did not work as intended, then you should probably discard the data from that session. However, if data from a substantial number of participants must be discarded on this basis—say, more than 20%—there may be something wrong with the design of the research, and you should try to find alternative designs that are less susceptible to demand characteristics, misperceptions, or suspiciousness. Wilson, Aronson, and Carlsmith (2010) recommend that researchers set specific criteria for excluding participants’ responses before data collection begins to ensure objectivity in the process. For example, decide in advance the factors that indicate if research participants are unduly suspicious of a deception.

The discovery function. Post-experimental discussions with research participants can sometimes suggest new hypotheses to researchers or lead them to look at old hypotheses in new ways. At the conclusion of a study about the role of spatial context of visual search, for example, Lleras and Von Mühlenen (2004, Study One) interviewed participants about the strategies they used to search for the target stimulus, a rotated black letter T, among a group of rotated black letter Ls. Some participants reported using an active strategy of searching for the letter, others reported using a passive strategy of waiting for the letter to “pop out” to them. In a follow-up study, Lleras and Von Mühlenen (2004, Study Three) tested the effectiveness of these two strategies by instructing participants to use either an active or passive search strategy. It is always useful to find out what your participants think about your research and the hypotheses you are testing; unencumbered by the blinders of accepted theory and methodology, they can provide new and useful insights.

Conducting the interview. Four functions are integrated into three steps that make up the post-experimental interview (Wilson et al., 2010). We will just outline the steps here; see Wilson et al. (2010) and Mills (1976) for detailed guidance. The first step is probing for effects of demand characteristics, suspiciousness, and misperception. Wilson et al. (2010) suggest that this step proceed by using three increasingly specific questions. First, ask participants what questions they have about the study or the procedures used. Participants’ questions can give hints about problems that the researcher can pursue with his or her own questions. The answers to the participants’ questions should be complete and truthful, thereby contributing to the educational function. Next, the researcher should specifically ask if the participant “found any aspect of the procedure odd, confusing, or disturbing” (Wilson et al., 2010, p. 76). If this probe does not bring out any problems, then the researcher can ask, “Do you think that there may have been more to this experiment than meets the eye?” (p. 76). Wilson et al. point out that almost everyone will answer yes to this kind of question (it is obviously high on demand characteristics). Therefore, you must be careful to sort out problems that are plausible, given the nature of the research, from responses that are likely given for social desirability reasons.

Participants’ responses to these probes can be used as a lead-in to the second step, explaining the research. If deception is used, the explanation will combine the ethical function of debriefing with the educational function of providing participants with information about the research (Mills, 1976). For example, Smeets, Stelgen, Ost, Jelicic, and Merckelbach (2009) studied what residents of the Netherlands recalled about the assassination of a well-known Dutch politician, Pim Fortuyn. This event was covered extensively in both national and international news, but none of the video footage showed the actual moment Fortuyn was shot. Smeets et al. asked participants if they had seen such footage; if they reported doing so, it was a false memory. During the debriefing, Smeets et al. provided detailed information about research on false memories. Those participants who reported seeing the footage were then given the opportunity to explain why they had reported seeing the nonexistent images; most reported that they misunderstood the question and thought it referred to images that did exist. Finally, Smeets et al. offered examples of plausible reasons for the false memory and probed whether participants were still convinced they had seen images of the actual assassination. Such extensive debriefing is important for this type of research as inaccurate memories can persist. However, as already noted, in nondeceptive research, the oral explanation can be brief and supplemented with a handout.

The third step is soliciting participants’ help in improving the research. Ask them for their comments on and criticisms of the research; as already mentioned, these comments can suggest topics for future research and may reveal methodological problems that have not yet come out in the interview. Wilson et al. (2010) note that this procedure can allow participants to voice qualms about the procedure or any deception that was used; you can then take further steps to address any adverse effects as Smeet et al. (2009) did. Finally, ask the participants not to discuss the research with anyone who might take part in it. As discussed in Chapter 7, knowledge of hypotheses or procedures can lead to reactivity and invalidate participants’ responses. Explain the reasons for confidentiality clearly and completely; such candor both educates participants about the problems of research and motivates them to comply with the request. The effectiveness of such requests is a matter of some debate, but Wilson et al. (2010) suggest that some of the noncompliance problem can be alleviated by telling participants what they can say if friends ask them about their research experience. For example, the experimenter could tell participants that it’s okay to describe general or superficial aspects of the procedure. Giving participants something explicit to say, such as “I watched a videotape and filled out a questionnaire about what I saw,” spares them the embarrassment of having to give friends an evasive response, such as “I’d prefer not to discuss it.” It also relieves them of the problem of having to invent an uninformative description of the experiment.

If two or more participants take part in the same research session, Aronson et al. (1990) recommend that they be interviewed separately. They note that it is difficult to assess two people’s reactions simultaneously, thus leaving the door open to the researcher’s missing a crucial word, gesture, or tone of voice. Also, someone might feel inhibited about asking a question or voicing a concern that the other people being interviewed don’t mention. In addition, in deception experiments participants might be embarrassed by being dehoaxed, and perhaps in their minds being made to look foolish, in front of a peer. Finally, although we have been discussing the post-experimental interview in terms of a face-to-face interaction, written questionnaires can also play a role, especially as a starting point for further discussion. Participants also might be more willing to make comments on questionnaires, especially anonymous questionnaires, than in a face-to-face conversation. For example, politeness might inhibit someone from saying something along the lines of “That was the stupidest cover story imaginable” in an interview, but the person might feel free to express critical comments in writing. Candor can be enhanced by having someone not associated with the experiment, such as a departmental secretary or office assistant, administer and collect the questionnaire.

So far, our discussion of research procedures has assumed that you, the person who designed the study, will be the person who collects the data. Sometimes, however, you might have research assistants who collect data for you. If so, you will be responsible for your assistants’ training in preparation for data collection and for how they treat research participants. In training your assistants, you must ensure that they are completely familiar with the research equipment and procedures and are able to answer participants’ questions. It can be useful for you to take the role of research participant and have your assistants collect data from you. This procedure lets you both assess your assistants’ levels of training and, by looking at the study from a participant’s point of view, catch any unforeseen problems with the procedures and materials. Also, ask your assistants any questions that participants might bring up so that you can see how well your assistants can answer them. You might also want to create problems for your assistants, such as by hiding an electronic timer left on a table, to see how well they can deal with unanticipated “glitches.”

When your assistants interact with research participants in pilot studies and during data collection, you should monitor their performance, both to ensure that they are following the correct research procedures and to ensure that they are treating participants courteously. It is best to do this directly, such as by sitting in the corner of the room when a group-administered questionnaire is being administered or by observing through a one-way mirror. If direct observation is not possible, you could interview research participants about your assistants’ behavior after explaining your supervisory role or by using a questionnaire. Make these assessments fairly frequently at the outset of data collection and periodically thereafter.

When discussing your observations with your assistants, be sure that your feedback is constructive. Be polite, point out what they did well in addition to any problems you noted, and give them specific guidelines for improving their performance. Always bear in mind that in this situation you are a teacher as well as a researcher, so you have an obligation to provide your assistants with an effective learning experience. Box 16.1 provides some guidelines for supervising research assistants.

• |

Set clear goals and objectives, such as the number of data collection sessions each assistant will conduct during a semester. |

• |

Set clear expectations for behavior, such as dress, punctuality, and interactions with research participants. |

• |

Clearly define each person’s role in the research process, such as who collects data, who enters data, who analyzes data, who supervises whom, and so forth. |

• |

Compile a laboratory manual that explains policies and procedures, give one to each assistant, and hold a meeting to check their understanding of its contents and to answer questions. Malfese et al. (1996) provide a sample outline for a lab manual. |

• |

Have a system for communicating with and among assistants. A periodic meeting can be very useful. |

• |

Being a researcher will be a new (and perhaps stressful) role for most assistants, so monitor them carefully for signs of uncertainty or stress and provide appropriate guidance. |

• |

Be alert for signs of conflicts between assistants, and take immediate action to resolve them. |

• |

Provide assistants with periodic performance feedback so that they know what they are doing correctly and incorrectly. Provide corrective feedback tactfully. |

Source: Adapted from Malfese et al. (1996).

Researchers are constantly looking for ways to collect data from a wide range of participants at minimal cost and the Internet (or World Wide Web) offers many possibilities for doing so. As Birnbaum (2001) notes, researchers can collect online data from participants who come to their laboratory or from people all over the world. Researchers are using online data collection procedures to answer an increasingly wide range of research questions. One common approach is to adapt materials developed for offline research into an online study; for example, researchers use this translational approach to convert paper and pencil personality measures to online surveys (Skitka & Sargis, 2005, 2006). For this type of Web-based research, potential participants are directed to a site where they see a page that describes the research. Interested respondents then click to go to a new page and give their informed consent to participate. Next, they are directed to the pages where the data are collected in the form of either a survey or an experiment. Once data are submitted, the debriefing page is available. Because most Web-based research takes this form (Skitka & Sargis, 2005, 2006), the data collection issues discussed in this section focus primarily on this type of research.

However, researchers also use novel approaches to testing research hypotheses using the Web that do not simply mirror procedures used in non-Internet-based research. For example, Rentfrow and Gosling (2003) downloaded the online music libraries of 10 individuals from each of the 50 United States. Seven judges then categorized the songs in these libraries by music genre; these ratings were found to be consistent with people’s self-reported music preferences. Researchers also study questions such as how changes in technology and our increasing use of Web-based social interaction affect people’s thoughts, feelings and behaviors; this phenomenological approach to Web-based research addresses a unique set of questions that did not arise before the advent of Internet-based communication (Skitka & Sargis, 2005, 2006). For example, Bacigalupe (2011) discussed how communication technologies, such as Facebook and Twitter, are changing the ways health care professionals interact with their patients in an environment that is asynchronous and not limited by geography. The methodologies used to conduct this type of research are similar to those used for other types of observational research, discussed in Chapters 2 and 10. Similarly, the procedures used in for coding qualitative research data, discussed in Chapter 14, can be applied to content analysis of information posted on the Web. Therefore, these topics are not discussed in detail in this chapter.

In this section, we present some of the issues involved in using the Internet for data collection: the validity of data collected over the Internet, the advantages and disadvantages of Web-based research, participant recruitment over the Web, and ethical issues in Internet research. This section will not deal with programming and other technical issues; those are well-covered in a number of sources (for example, Birnbaum, 2010; Fraley, 2007). Moreover, there are a number of commercial data collection programs, such as SurveyMonkey and MySurveyLab, available to assist researchers with online data collection. The quality of these applications continues to improve, as does their ease of use, so relatively few programming skills are needed to conduct most online research.

A question that concerns Internet researchers is that of the validity of their data. Not only are those data being collected by a novel means that could affect results, but the demographic characteristics of participants often differ from those of college students, the most commonly used research population (Krantz & Dalal, 2000). In some situations, people behave differently on the Internet than in in-person interactions, primarily by being less inhibited and more self-disclosing (Joinson, 1999).

Several studies have addressed the question of data validity by examining the extent to which the results of Web-based studies match those of laboratory studies. The available research suggests that data from Web-based surveys are similar to that obtained from high quality paper-and-pencil studies and may be superior in some ways (Skitka & Sargis, 2006), an issue we return to later. Similarly, McGraw, Tew, and Williams (2000) found that the quality of data collected using Web-based experiments was similar to that collected in traditional lab experiments. This equivalence was found even for studies requiring precise measurements, such as response time, that might be affected by characteristics of the users’ computers. Krantz and Dalal (2000) concluded that the results of all forms of research conducted over the Internet—surveys, correlational studies, and experiments—converge very well with the results of their laboratory counterparts. It would therefore seem that data collected in well-designed Internet research is as valid as data collected by traditional means.

Researchers who use the Internet to collect data have noted a number of advantages that the medium provides. These include economy and ease of data collection, access to nonstudent and special populations, the potential for increasing some aspects of the internal validity of research, and the public nature of the research process.

Economy and ease of data collection. Just as the introduction of the desktop computer was supposed to create the paperless office, data collection using the Internet (and data collection via computers generally) allows for paperless surveys and other forms of research. When researchers use computers to collect data there is no need for physical copies of surveys or data record forms: Participants enter their responses directly into a computer file, eliminating printing costs. Furthermore, the data files can be transferred directly to the computer program used to analyze the data, thereby eliminating the errors that can creep in when data are transcribed from paper records to computer files. Informed consent can be recorded online, eliminating the need for paper copies, and instructions can be presented on the computer screen. The postage costs incurred by mailing surveys are also eliminated with Internet research. Researchers who collect interview data on the Web rather than though telephone surveys also realize significant cost savings (Kraut et al., 2004).

The Internet can also make data collection easier for participants (Reips & Krantz, 2010). Because Web pages are usually available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, participants can take part in the research when and where it is convenient for them to do so; for example, McGraw et al.’s (2000) participants completed their study at all times of day and night. Researchers benefit from online research because they do not need to schedule specific blocks of time for data collection, and they do not waste time waiting for late or no-show participants. Many studies require collecting data from one participant at a time, so inperson data collection may have to be carried out over a long period of time, reducing the timeliness of the research results. In contrast, the Internet can provide a large number of participants very quickly (Anderson & Kanuka, 2003). As Birnbaum (2000) reported, “Compared to my usual research, which typically takes 6 months to collect data for 100 college students, it was quite pleasant to collect 1224 sets of data in 4 months and 737 in the next 6 weeks” (p. 25). Internet research may be especially beneficial to researchers at small colleges and universities, where the potential number of research participants is small, and to researchers at institutions that do not have subject pool systems.