Proximal versus distal program outcomes

Sources of implementation failure

Program Monitoring and Program Development

Criteria for Evaluating Impact

Answering the Research Questions

What aspects of the program are important?

How can the program be improved?

How valid is the theory of the program?

When “null” results are not null

Criteria for Research Utilization

Reliability of Difference Scores

Suggestions for Further Reading

Questions for Review and Discussion

The knowledge generated by theory and research in the behavioral sciences is often applied in attempts to solve practical problems. Psychotherapies are developed from theory and research on abnormal psychology, workplace interventions derive from theory and research in industrial and organizational psychology, and educational reforms are based on theory and research on the teaching-learning process. Some interventions are directed at bringing about change in individuals or in small groups of people. Other programs are intended to have a broader impact on the general social framework of a city, state, or country. Such broad-based programs include Project Head Start, designed to improve preschoolers’ readiness for our educational system, educational television programs, such as Sesame Street, designed to enhance young children’s basic cognitive and social skills, and school desegregation programs, designed to improve the educational opportunities of minority group students.

Evaluation research, or program evaluation, is the application of social and behavioral research methods to determine the effectiveness of a program or an intervention. Effectiveness can be defined in terms of four questions (Lambert, Masters, & Ogles, 1991):

• |

To what extent did the program achieve its goals? Goal achievement can be defined relative to a no-treatment or placebo control group or to the effectiveness of some other intervention designed to achieve the same goals. |

• |

What aspects of the program contributed to its success? Most intervention programs are complex, composed of many parts. An evaluation can be conducted to determine which of those parts are critical to the success of the program and which could be eliminated without harming the program’s effectiveness. |

• |

How can the effects of a program be improved? For example, if a successful 10-week program is increased in length to 20 weeks, is there a commensurate increase in benefit? |

How valid is the theory underlying the program? Many interventions are explicitly based on theory, and all include at least an implicit model of the processes by which the program should have an effect. The validity of the theory underlying the program has implications for the generalizability of the program and for interpreting situations in which the program has no effect. |

Evaluation research has emerged as a major branch of the behavioral sciences; consequently, only a brief overview of the field can be conducted in a single chapter. In this chapter we examine the five stages of evaluation research—defining the goals of the program, monitoring the implementation of the program, assessing the program’s impact, analysis of the cost efficiency of the program, and utilization of the results of the evaluation. In addition, because an effective intervention implies bringing about change, we conclude the chapter with a discussion of some issues in the measurement of change. More detailed information on theory and process of evaluation research is available in the books in the suggested reading list at the end of this chapter.

Every intervention program has goals—it is intended to accomplish something. To evaluate the degree to which a program has attained its goals, those goals must be defined both conceptually and operationally. Goal definition begins with needs assessment, the process of determining that a problem exists and of designing a solution for the problem—the intervention program. An evaluability assessment examines a program to determine the information necessary to conduct an evaluation. An important part of goal definition is the inclusion of goals as defined by all the stakeholders in the program, the people who are affected by the program and its success or failure. Finally, it is important to explicate the theory underlying the program.

Before program administrators set goals for their programs, they have to know what needs the program must meet. The needs assessment aspect of goal definition involves identifying the problems that a program must solve and developing possible solutions for it to implement.

Identifying problems. Every intervention program begins with a needs assessment, the determination that a problem exists and that something should be done about it. The determination that a problem exists can derive from many sources. Social indicators are continuing measures of various social phenomena such as crime rates, unemployment rates, admissions to psychiatric care facilities, and so forth. An increase in a negative social indicator, such as crime rates, could lead to the determination that crime is a problem. Problems can also be identified through surveys conducted to assess people’s perceptions of needed community services. Finally, the determination that a problem exists could stem from a policy maker’s intuition that something is wrong. Regardless of the source of the perception of need, careful research should be conducted to verify that a need, in fact,exists. If a program is implemented to solve a nonexistent problem, it cannot be effective: If the problem rate is zero or near-zero, it cannot go any lower. For example,

After a social intervention designed to prevent criminal behavior by adolescents was put in place in a Midwestern suburb, it was discovered that there was a very low rate of juvenile crime … in the community. The planners had assumed that because juvenile delinquency was a social problem nationally, it was a problem in their community as well. (Rossi, Freeman, & Lipsey, 1999, p. 121)

Developing solutions. Once a problem has been identified, a solution—an intervention program—must be developed. Two important considerations in solution development are identifying the client population (the people to be served by the intervention) and the content of the program (the services to be provided to the client population). It is important to identify the client population because if the service is delivered to the wrong people, the problem cannot be solved. For example,

A birth control project was expanded to reduce the reportedly high rate of abortion in a large urban center, but the program failed to attract many additional participants. Subsequently it was found that most of the intended urban clients were already being adequately served and a high proportion practiced contraception. The high abortion rate was caused mainly by young women who came to the city from rural areas to have abortions. (Rossi et al., 2004, p. 104)

To design an effective change program, you must know the causes of the phenomenon to be changed so that you can design the program in ways that can bring about the desired change. Ideally, program design will be based on theory and research that address policy-relevant independent variables and high-utility dependent variables (Ruback & Innes, 1988). Although such theory-based program designs may be common for “micro” level interventions such as psychotherapy and workplace and educational interventions developed by scientist-practitioners, they are not as common for interventions aimed at broader social problems, which are often developed by policy makers not trained in the social and behavioral sciences. Rossi et al. (2004) note that “Defining a social problem and specifying the goals of intervention are … ultimately political processes that do not follow automatically from the inherent characteristics of the situation” (p. 107). For example, in reviewing legislation intended to reduce adolescent pregnancy, the U.S. General Accounting Office “found that none of the pending legislative proposals defined the problem as involving the fathers of the children in question; every one addressed adolescent pregnancy as an issue of young mothers” (Rossi et al., 2004, p. 107).

Once a problem has been identified and a program has been developed to address the problem, the next step in the evaluation process is evaluability assessment. In this step, the evaluation team identifies the types of information needed to determine how much impact the program had and why it had that level of impact (Wholey, 1987). To conduct an evaluation, the evaluators must know

• |

The goals of the program, the expected consequences of achieving those goals, and the expected magnitude of the impact of the program on the consequences; |

The theory of the program that links the elements of the program to the expected consequences, explaining how the program will have its effects; | |

• |

The implementation guidelines for the program, explaining how the program is to be carried out so that it has the expected consequences; that is, how the theory will be put into practice; |

• |

The resources the program needs to achieve its goals effectively. |

During the evaluation process, the evaluation team will collect data on all these issues to understand why an effective program worked and why an ineffective program did not. Evaluations that look only at outcomes cannot answer the question of why a program succeeds or fails. This question is important because a negative evaluation outcome, in which a program appears to have no effect, can have causes other than a poorly designed program; if these other causes of failure can be removed, the program could be effective. Now, let’s look at the process of specifying the goals of the program; the issues of theory, implementation, and resources will be considered shortly.

Goal specification. To evaluate the success of a program, you must be able to measure goal attainment; to be measurable, goals must be clear, specific, and concrete. Most programs have some kind of statement of goals in the form of a mission statement, public relations materials, or part of the funding application. However, Weiss (1998), points out that not all programs have clear goal statements. In that situation

if the evaluator asks program staff about goals, they may discuss [goals] in terms of the number of people they intend to serve, the kinds of service they will offer, and similar process information. For program implementers, these are program goals in a real and valid sense, but they are not the primary currency in which the evaluator deals. She is interested in the intended consequences of the program.

Other programs have goal statements that are hazy, ambiguous, or hard to pin down. Occasionally, the official goals are merely a long list of pious and partly incompatible platitudes. Goals, either in official documents or program managers’ discussion, can be framed in such terms as improve education, enhance the quality of life, improve the life chances of children and families, strengthen democratic processes. Such global goals give little direction for an evaluator who wants to understand the program in detail. (p. 52; italics in original)

In such cases, it becomes part of the evaluation researcher’s job to elicit specific measurable goals from the program’s staff.

To illustrate the process of goal specification, let’s take the example of the goal improve education. As shown in Box 18.1, there can be many viewpoints on what constitutes educational improvement. Every program involves a variety of stakeholders, and, as we discuss shortly, every stakeholder group can have a different set of goals for the program. Potential stakeholders in educational programs include the school board, school administrators, teachers, parents, and students. So, from the students’ viewpoint, educational improvement can have many possible meanings, each of which, such as interest in the material, can have several behavioral consequences. Each consequence can, of course, be measured in several ways. If this process of goal specification sounds familiar, look back at Figure 5.2, which dealt with the process of refining a topic into a research question. In each case, the researcher is trying to move from generalities to specifics. One difference is that while the typical research project focuses on one or a few research questions, the evaluation research project seeks to assess as many of the program’s goals as possible.

A broadly stated goal can have many different meanings depending on the point of view taken and how it is operationally defined.

Goal

“Improve education”

Possible Points of View

School board

School administrators

Teachers

Parents

Students

Possible Meanings of “Improve Education” for Students

Students enjoy classes more

Students learn more

Students can apply what they have learned

Students show more interest in school

Possible Behavioral Indicators (Operational Definitions) of Increased Interest

Students participate more in class discussion

Students ask more question

Students do outside reading

Students talk to parents about their course

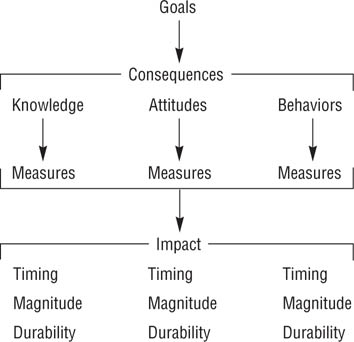

Figure 18.1 shows the issues to consider in goal specification (Weiss, 1998). Each abstract goal must be specified in terms of specific consequences that can be operationally defined. Consequences can fall into three categories: knowledge, or what clients should know as a result of the program; attitudes, or what clients should believe as a result of the program; and behaviors, or what clients should do as a result of the program. Measures must then be selected or developed for each specified consequence. The specification process must also lay out the expected impact the program will have on each measure. Impact specification consists of stating the expected timing of effects, magnitude of effects, and durability of effects.

Program Goals, Consequences, and Impact.

A program can have many consequences, the impact of which can be assessed in terms of their timing, magnitude, and durability.

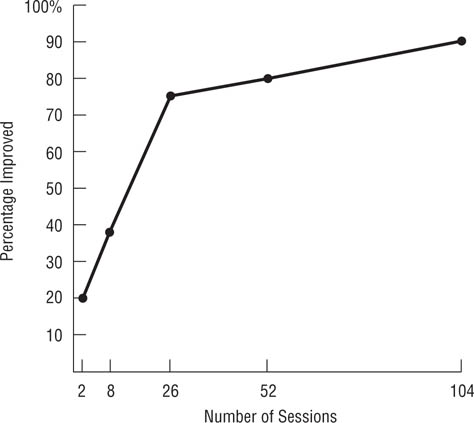

Timing concerns when during the course of a program an effect should occur. Consider, for example, Figure 18.2, which shows the cumulative percentage of psychiatric patients rated as improved as a function of the number of therapy sessions. If one defined program success as improvement in at least 50% of the patients, then a psychotherapy program would require at least 10 sessions to be successful; if the success criterion was improvement in 75% of the patients, then at least 26 sessions would be required to meet that success criterion. Magnitude concerns the question of how much of an impact a program should have, or the effect size of the program. As with other research, the smallest effect size that would have practical significance should be specified for each measure. Durability concerns the question of how long the effects should last after clients leave the program: Should the effect be permanent or temporary? Should the magnitude of the effect stay the same after the client leaves the program, or should it be expected to diminish? If it should diminish, at what minimum level should it be maintained? What is a reasonable follow-up period over which to assess the maintenance of effects?

A final aspect of goal specification is determining the relative importance of the goals and their consequences. In any program, some goals are going to be more important than others, and within goals some consequences are going to be more important than others. Specifying the relative importance of goals is necessary for two reasons. First, the resources for conducting the evaluation might not support the assessment of all goals or of all consequences of a goal. Agreement on the relative importance of goals and consequences allows the evaluation team to focus on the most important ones. Second, if the evaluation finds that some goals have been achieved and others not, determining the degree of program success can be based on the relative importance of the attained versus nonattained goals. Getting people to specify the relative importance of goals and consequences can be a difficult process, but there are standard techniques to facilitate the process (see, for example, Edwards & Newman, 1982).

Relation of number of Sessions of Psychotherapy and Percentage of Patients Improved.

How successful a program appears to be may be a function of when the outcomes are measured. (Adapted from Howard, Kopta, Krause, & Orlinski, 1985)

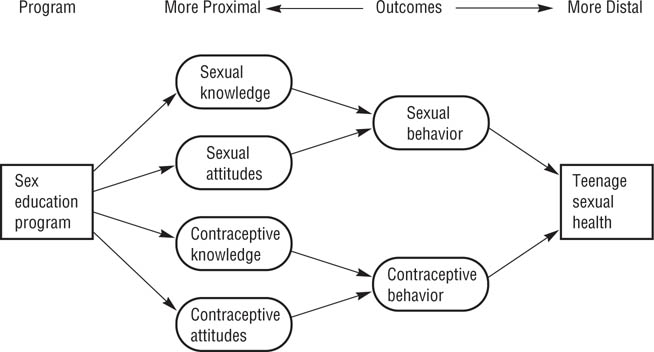

Proximal versus distal program outcomes. In considering the consequences or outcomes of a program, it can be useful to distinguish between proximal and distal outcomes. Proximal outcomes are direct effects of the program and can be expected to occur while the clients are taking part in the program. Distal outcomes are indirect effects of the program and occur only after the client has completed the program, occur in environments not controlled by the program, or occur at a higher level of analysis than that addressed by the program. Consider, for example, the hypothetical sex education program diagrammed in Figure 18.3. The program is designed to increase teenagers’ sexual knowledge and to induce more positive attitudes toward using contraception. These knowledge and attitude changes represent proximal outcomes. Changes in knowledge and attitudes are expected to result in changes in sexual and contraceptive behavior, which can also be considered reasonably proximal effects of the program, but are also somewhat distal because the program cannot affect them directly. More distal expected outcomes are fewer pregnancies among the program’s clients, a lower overall teenage pregnancy rate, and lower rates of sexually transmitted diseases.

Distal outcomes are also called social impact outcomes (Kazdin, 2003) because they take place in the client’s broader social environment outside the program and are often reflected in social indicators. Because distal effects take place outside the scope of the program, they can be considered indicators of the program’s ecological validity, answering the question of whether the program affects clients’ behavior outside the limited environment of the program itself. For example, no matter how much the sex education program changed its clients’ sexual knowledge, if that knowledge does not result in behavioral changes, the program has been ineffective in terms of society’s concerns about teenage sexual health. This example also indicates a limitation on a program’s ability to bring about distal effects: Not all causes of the distal effect are under the program’s control. For example, it is not only teenagers’ sexual and contraceptive knowledge and attitudes affect their sexual and contraceptive behavior—so do those of his or her sexual partner, who may not be not included in the program. Despite this problem, however, intervention programs can have significant distal effects (Kazdin, 2003).

FIGURE 18.3

Theory of Program Effects for Hypothetical Sex Education Program.

The program is designed to change sexual and contraceptive knowledge and attitudes, which are expected to affect behavior and thereby improve sexual health.

The role of stakeholders. As noted earlier, every intervention program has stakeholders who have interests in the outcome of the program. Common stakeholder groups in a program include (Rossi et al., 2004):

• |

Policy makers who decide whether the program should be started, continued, expanded, curtailed, or stopped; |

• |

Program sponsors, such as government agencies and philanthropic organizations, that fund the program; |

• |

Program designers who decide on the content of the program; |

• |

Program administrators who oversee and coordinate the day-to-day operations of the program; |

• |

Program staff who actually deliver the program’s services to its clients; |

• |

Program clients who use the services of the program; |

• |

Opinion leaders in the community who can influence public attitudes toward the program and public perceptions of its success or failure. |

Each of these groups can have different, and sometimes conflicting, goals and expected consequences for the program. To take a simple example, Edwards and Newman (1982) describe the decision to select a site for a drug abuse treatment program. In terms of relative importance, the program staff rated good working conditions—such as large offices, commuting convenience, and availability of parking—as being about twice as important as easy access for clients, which they rated as being about twice as important as adequate space for secretaries. It would not be surprising if two other stakeholder groups—the clients and secretaries—rated the relative importance of these aspects of the site differently. A successful assessment requires that the evaluation team identify all the stakeholder groups, determine their goals and expected consequences for the program, and resolve conflicts in goals and in the relative importance of goals. Failure to do so can result in a situation that will allow a stakeholder group that doesn’t like the outcome of the evaluation to reject it as flawed. As Weiss (1998) notes, this aspect of the evaluation requires that evaluators have excellent negotiation and mediation skills.

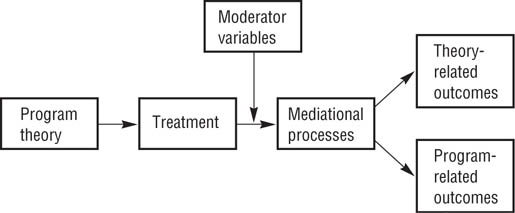

The role of program theory. As shown in Figure 18.4, the theory of a program specifies the kinds of treatments clients should receive. The theory also specifies the expected outcome of the treatment in terms of variables relevant to the theory and those relevant to the program’s goals. Finally, the theory specifies the moderating variables that can limit the effectiveness of the treatment and the mediating variables that come between the treatment and the outcome. For example, Hackman and Oldham’s (1980) model of job design describes interventions that should lead to improved work motivation and job satisfaction. However, the model also specifies that these effects will be found only for people who have the skills required to do the job well and who expect to get high levels of satisfaction from doing their jobs. These worker characteristics moderate the effect of the treatment. As you can see in Figure 18.3, sexual and contraceptive knowledge, attitudes, and behavior are mediator variables that come between the treatment and its expected effects: The treatment changes knowledge and attitudes, which change behavior, which in turn affects sexual health.

Role of Program Theory in Evaluation.

The theory specifies the treatment and the variables that moderate and mediate the effect of the treatment on the program’s expected outcomes.

An intervention program can be designed around an existing theory, or the theory might be implicit in the components and goals of the program. In the latter case, the evaluation team must help the program’s designers, administrators, and staff explicate the theory. Conducting a theory-based evaluation requires the measurement of estimator variables, such as those shown in Figure 18.3, as well as measurement of the program’s consequences and, in some cases, measurement or manipulation of program policy variables as independent variables. As you will recall from Chapter 5, policy variables are aspects of the situation that program administrators can manipulate, whereas estimator variables are outside administrators’ control but still affect program outcomes. Estimator variables are often psychological states, as illustrated by the more proximal outcomes in Figure 18.3, and, as shown in the figure, mediate the impact of treatment.

Including the program theory in the evaluation has several advantages (Chen, 1990; Weiss, 1998). First, if the program is based on an existing theory, the program functions as a test of the validity of the theory, as in the action research model described in Chapter 2. Second, testing the effects of the various components of the program allows one to determine which components are necessary to accomplish the goals of the program and which are not. Eliminating unneeded components can reduce the cost of the program. Third, the theory should specify the conditions necessary for the program to bring about its intended effects, as does Hackman and Oldham’s (1980) model of work redesign. If the conditions necessary for the success of the program are not met, the program cannot succeed. Finally, if a program is not effective, the theory might suggest reasons why. For example, a program might not have had its intended effects on the estimator variables that were supposed to affect the dependent variables. If the hypothetical program illustrated in Figure 18.3 did not result in a lower pregnancy rate, perhaps the program did not have the intended effect on the participants’ sexual and contraceptive knowledge or behavior.

A program must be carried out as designed; otherwise, it will not have its intended effects. Program monitoring involves continuing assessment of how well the program is being implemented while it is being carried out. This process is also called process evaluation or formative evaluation because monitoring evaluates the process or form of the program, in contrast to summative evaluation, which addresses the overall effectiveness of the program relative to its goals. In the following sections, we briefly examine three major aspects of program monitoring—delivery of services to the intended client (or target) population, program implementation, and unintended effects—and we consider the implications of program monitoring for carrying out the program and for the evaluation process.

Every program is designed to have an effect on a particular group of people, such as adolescents or substance abusers. If a program is not reaching the members of this target population, it cannot affect them. The fact that a program has been established does not mean it is reaching its target population; a program should therefore include an advertising component to ensure that members of the target population know about the program and an outreach component to persuade them to make use of the program (Rossi, Lipsey, & Freeman, 2004).

Once potential clients are aware of the program and begin to use it, there can be problems of bias in accepting people into the program. It is not uncommon for programs to enroll clients selectively, leaving some subgroups of the target population unserved. Selective enrollment usually operates to ensure that only those potential clients who appear most likely to benefit from the program or with whom the program staff feel most comfortable enter the program. This process has three consequences. First, not all the people in need of the program’s services receive them, and those who do receive the services may need them less than those not selected. Second, selective enrollment threatens the internal validity of the evaluation. Evaluations frequently use members of the target population who are not enrolled in the program as the control group in an experimental or quasi-experimental research design. If the characteristics of the program enrollees differ from those not enrolled, these characteristics are confounded with the treatment and control conditions of the research design, presenting alternative explanations for the outcome of the evaluation. Finally, selective enrollment threatens the generalizability of the program: If the evaluation finds the program to be effective but the program enrolls only a subgroup of the target population, there is no way of knowing if it will be effective for the other members of the target population. For example, would a pregnancy prevention program that is effective for European American teenagers also be effective for members of minority groups? There is no way to know unless minority group members are included in the program when it is carried out and evaluated.

These potential problems mean that the evaluation team must check to ensure that the program is reaching all members of the target population. This checking starts with the program goals: Whom is the program supposed to serve? The team can then review program records and interview clients to determine the characteristics of clientele being served. These characteristics can be checked against the program goals and against results of surveys of potential clients not enrolled in the program. If the enrolled clients differ from the target population described in the goals or from unenrolled potential clients, the team must modify the program to reach these groups.

The assessment of program implementation deals with the question of whether the program is being carried out as designed: that is, to compare what is actually happening in the program to what is supposed to happen. A program consists of a specific set of experiences that each client undergoes; if clients are not receiving these experiences, the program is not being implemented properly. For example, Feldman, Caplinger, and Wodarski (1983) evaluated the effectiveness of two treatment programs for antisocial youths. The programs organized youths into groups supervised by an adult leader. One program used traditional group social work, focusing on group processes, organization, and norms, whereas the other program used behavior modification techniques, using reinforcement contingencies to change behavior. A third, minimal-treatment “program” was actually a placebo control condition, in which no structured intervention was supposed to take place. However, process evaluations indicated that only 25% of the leaders in the group social work program and 65% of the leaders in the behavior modification program implemented their treatments correctly. In addition, 44% of the leaders in the placebo program carried out some form of systematic intervention. It was not very surprising, therefore, that the summative evaluation found few differences in the effects of the three treatment programs. This section briefly examines three aspects of implementation: sources of implementation failure, assessing implementation, and client resistance to the program.

Sources of implementation failure. There are a number of potential sources of implementation failure. One is a lack of specific criteria and procedures for program implementation. Every program should have a manual that describes the program’s procedures, techniques, and activities in detail. The manual can also provide the evaluation team with a basis for determining the degree to which the program is being implemented. A second potential source of implementation failure is an insufficiently trained staff. The staff must be thoroughly trained and tested on their ability to carry out the program as described in the manual. Third, inadequate supervision of staff provides opportunity for treatments to drift away from their intended course. Any program must, to some degree, be tailored to each client’s needs; however, it cannot be tailored to the extent that it departs from its intended form.

A fourth source of failure can arise in situations in which a novel treatment program is implemented with a staff who do not believe in its effectiveness, who are used to doing things differently, or who feel threatened by the new procedure. Such a situation can lead to resistance to or even sabotage of the program. For example,

A state legislature established a program to teach welfare recipients the basic rudiments of parenting and household management. The state welfare department was charged with conducting workshops, distributing brochures, showing films, and training caseworkers on how low-income people could better manage their meager resources and become better parents.…

Political battles [among stakeholder groups] delayed program implementation. Procrastination being the better part of valor, no parenting brochures were ever printed; no household management films were ever shown; no workshops were held; and no caseworkers were ever trained.

In short, the program was never implemented.… But it was evaluated! It was found to be ineffective—and was killed. (Patton, 2008, pp. 309, 310)

Assessing implementation. The assessment of implementation is not an easy matter. Programs are complex, and absolute criteria for correct implementation are rarely available. Nonetheless, criteria for deciding whether a program has been properly implemented must be established, even if they are somewhat arbitrary (Kazdin, 2003). For example, Feldman et al. (1983) randomly sampled and observed meetings held by group leaders during three phases of their treatment programs for antisocial youth.

The observers [who were unaware of treatment condition] were asked to mark which of three leadership styles best exemplified each leader’s behavior. Respectively, the selection categories described leader behaviors that typically were associated with the minimal, behavioral, and traditional methods of group treatment.…

A treatment method was considered to be unimplemented when the observer recorded the proper leadership style for none or only one of the three treatment periods. In contrast, an implemented method was one in which the group leader properly applied the assigned method for at least two of the three treatment periods that were observed. (Feldman et al., 1983, p. 220; italics in original)

As in the case of the goals and desired consequences of the program, implementation criteria should be established in consultation with stakeholder groups to ensure that all points of view on proper implementation have been considered (Patton, 2008).

Client resistance. Resistance to a program can come not only from staff, but also from clients and potential clients (see, for example, Harvey & Brown, 1996; Patton, 2008). For example, many members of disadvantaged groups distrust programs sponsored by government agencies and other “establishment” groups, and so may be suspicious of the goals of the program and reluctant to take part. Resistance also arises when people are uncertain about the effects of the program, resulting from anxiety over having to deal with the unfamiliar new program and, in some cases, disruption of daily routines. The structure and implementation of the program can also arouse client resistance or reluctance to use the services. Some of these factors include

• |

Inaccessibility, such as a lack of transportation, restricted operating hours, or locating the service delivery site in an area that clients perceive as dangerous; |

• |

Threats to client dignity, such as demeaning procedures, unnecessarily intrusive questioning, and rude treatment; |

• |

Failure to consider the clients’ culture, such as lifestyles, special treatment needs, and language difficulties; |

• |

Provision of unusable services, such as printed materials with a reading level too high for the clients or with a typeface too small to be read by visually impaired clients. |

Client resistance can be reduced by taking two steps (Harvey & Brown, 1996; Patton, 2008). The first is including all stakeholder groups in the design of the program to ensure that all viewpoints are considered. Focus groups (see, for example, Puchta, 2004) can be used for this purpose by providing members of stakeholder groups with information about the goals and structure of the program and soliciting their comments and suggestions. The program can then be modified to address concerns the group members raise. Second, informational programs can alleviate potential clients’ uncertainties about the program by explaining any unchangeable aspects of the program that caused concern for members of the focus groups. Focus groups can also suggest ways to present the information that will facilitate acceptance of the program by members of the target population. Even when these steps have been taken, however, process evaluations should include assessment of clients’ perceptions of the program and the sources of any reservations they express about it.

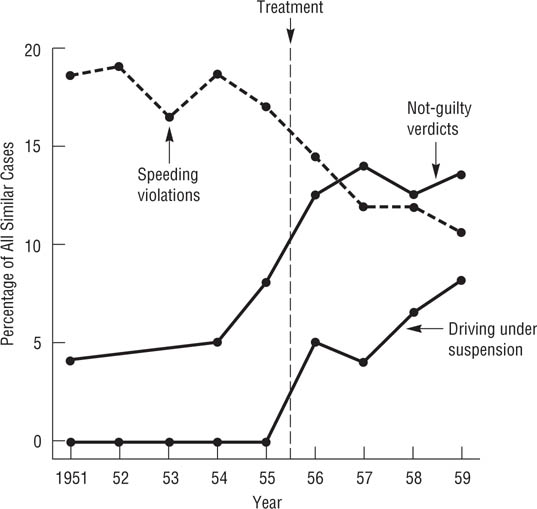

Every program is intended to bring about certain effects, as defined by its goals and their expected consequences. Programs also bring about unintended effects, and one function of process evaluation is the identification of these side effects (Weiss, 1998). Campbell (1969b) described a classic case of unintended effects. In 1956 the governor of Connecticut ordered the state police to crack down on speeders and encouraged judges to suspend the driving licenses of offenders as a way of reducing highway deaths. As the broken line in Figure 18.5 indicates, the program was successfully implemented: The number of speeding violations declined after the program was started. However, the two solid lines in Figure 18.5 suggest the program had at least two unintended negative consequences: Fewer drivers charged with speeding were found guilty, and the frequency of people driving with a suspended license increased.

Intended and Unintended Effects of an Intervention.

The Connecticut speeding crackdown had its intended effect of decreasing the number of speeding violations (broken line) but had the unintended effect of more “not guilty” verdicts when speeding tickets were challenged in court and more arrests for driving with a suspended license. (Data from D. T. Campbell, 1969b)

In the worst case, unintended effects can exacerbate the problem a program was intended to alleviate. For example, there have been a number of programs designed to reduce problem behaviors, such as delinquency and alcohol and tobacco use, among adolescents. Dishion, McCord, and Poulin (1999) conducted a series of evaluations of one such program that used a group-based format to promote prosocial goals and self-regulation of behavior among teenagers. Although “many of the short-term effects were quite positive” (Dishion et al., 1999, p. 757), Dishion et al. found that over a 3-year follow-up period, the teens in the intervention group were more likely than those in a placebo control group to increase their tobacco and alcohol use and to engage in delinquent and violent behavior. In addition, the teenagers “with the highest initial levels of problem behavior were more susceptible to the [unintended negative] effect” (Dishion et al., 1999, p. 758).

Unintended positive effects are also possible but are, perhaps, less likely to be reported because they are not defined as problems. Process evaluation must be able to identify unintended effects, both positive and negative. Because these effects often cannot be identified in advance, the evaluation team must conduct observations, personal interviews, and surveys with all stakeholder groups throughout the course of the program in order to detect them.

Program monitoring is conducted to ensure that the program is being carried out as designed and to identify departures from the design. If problems are noted, program administrators will take steps to correct them. While these corrections are good for the program and, indeed, are the desired outcome of process evaluation, they can create a dilemma for the summative evaluation. On the one hand, corrections ensure proper implementation of the program, so the summative evaluation can determine the effectiveness of the program as designed. On the other hand, summative data collected while the program was off track may have to be discarded as “bad,” not reflecting the true effects of the program. Discarding data not only offends the aesthetic sense that most researchers have concerning the proper conduct of research, it also means additional work: The discarded data must be replaced by collecting data from clients of the revised program. However, such “bad” data need not always be discarded. These cases can be considered to represent the effects of an alternate form of the program that can be compared to the effects of the program as designed. For example, if improper implementation led to the omission of a component from the program, the data from that version of the program, when compared to the full program, can indicate the importance of the component: If both versions of the program are successful, then the omitted component is not a necessary part of the program.

The impact assessment stage of evaluation research addresses the question of how much effect the program had on its clients in terms of achieving its goals. Data are collected and analyzed in order to make a summative evaluation of the program’s effect. Four aspects of impact assessment are the criteria for evaluating the impact of a program, designs for answering the questions posed in evaluation research, choice of research methods, and interpretation of null results.

What standards can one use to decide whether a program is effective or ineffective? Kazdin (2003) suggests several sets of criteria, outlined in Box 18.2: the degree of change brought about by the program, the importance of the change, the costs of the program, and the acceptability of the program to stakeholders.

Degree of Change

Importance of Change

Proportion of clients who meet goals

Number of goals achieved per client

Durability of outcome

Costs of the Program

Administrative Costs

Length of treatment

program Method of providing treatment

Required qualifications of staff

Costs to clients

Monetary

Negative side effects of program

Costs to staff

Workload

Other sources of stress

Acceptability of Program to Stakeholders

Clients

Staff

Administrators

Sponsors (funding agencies)

Advocacy groups for the client population

Note: Adapted from Kazdin, 2003

Degree of change. The simplest way of looking at program impact is in terms of the degree of change brought about relative to each of the goals and desired consequences of the program. The change experienced by each client of the program relative to a goal can be averaged across clients to provide an index of the program’s effect on that goal. The mean change can be tested for statistical significance to determine if it represents real change, and can be compared to the mean change found in a control group to determine if the program had an effect over and above those of history, maturation, and so forth (see Chapter 7). In addition, you can calculate an effect size index as an indicator of the degree of a program’s effect.

However, be cautious in using mean change as an indicator of a program’s effect: A group average can obscure individual differences in response to a treatment. For example,a program could have positive effects for some clients and negative effects for others, leading to no change on the average. Conversely, a program that had large effects for some clients but little effect for the rest could result in a statistically significant mean change. It is therefore useful to supplement analyses of mean change with other indicators of effectiveness, such as the percentage of clients who show an important degree of change.

Importance of the change. As noted in Chapter 17, neither statistical significance nor effect size necessarily says anything about the practical importance of an effect. Program administrators are most likely to define effect importance in terms of the percentage of clients who meet the program’s goals: The more clients who meet the goals, the more effective the program (Jacobson & Truax, 1991; Kazdin, 2003). Goal attainment can be operationally defined either in terms of meeting some preset criterion of improvement or relative to the level at which an outcome is found in a criterion population. For example, Klosko, Barlow, Tassinari, and Cerny (1990) compared the effects of psychotherapy and medication for panic attacks with two control groups. The two treatments brought about the same amount of change in terms of mean scores on a set of outcome measures. However, using an absolute measure of improvement—zero panic attacks over a 2-week period—87% of the psychotherapy group had improved compared to 50% in the medication group and 36% and 33% in the two control groups.

Jacobson and Truax (1991) suggest three possible ways of operationally defining improvement relative to a criterion population. Under the first definition, a client would be considered improved if his or her outcome score fell outside the range of scores of an untreated control population, with “outside the range” defined as two or more standard deviations above the mean of the untreated group. That is, improvement is defined as no longer needing the program; for example, a psychotherapy patient improves to the point of no longer being considered dysfunctional. Under the second definition, the score of a client determined to be improved would fall within the rage of scores of a population not in need of treatment, with “within the range” defined as no more than two standard deviations below the mean of the criterion group. That is, improvement is defined in terms of joining the criterion population; for example, a psychotherapy patient improves to the point of being considered “normal.” Under the third definition, the score of a client determined to be improved would fall closer to the mean of the population not in need of treatment than to the mean of the population in need of treatment. That is, a client may improve but still need treatment. Nezu and Perri (1989) used the second definition to evaluate the effectiveness of a treatment for depression and found that 86% of the treated clients scored within the normal range on a commonly used measure of depression compared to 9% of the members of an untreated control group.

A second indicator of the importance of the change brought about by a program is the number of goals achieved. Most programs have multiple goals, and a more effective program will achieve more of its goals or at least more of its goals defined as important. For example, the evaluation of the first year of Sesame Street found the program did not meet one of its stated goals: The “achievement gap” (disadvantaged children’s doing less well in primary school than better-off children) it was designed to reduce increased rather than decreased. Yet the skill levels of the disadvantaged children did improve, which itself could be considered a significant accomplishment of the program, especially given its relatively low cost (Cook et al., 1975).

A third indicator of importance is the durability of the outcomes. It is not unusual for program effects to decay over time, with the greatest effect being found immediately after completion of the program. For this reason, every program evaluation must include appropriate follow-up data to determine the long-term effects of the program. Evaluation of goals that are distal in time, such as the academic effects of preschool enrichment programs, may require very long-term follow-ups. Follow-up research can be arduous because it may be difficult to locate clients once they complete the program and to keep track of members of control groups. Nonetheless, follow-ups are essential for evaluating the effectiveness of a program (Dishion et al., 1999).

Costs of the program. A second set of factors to consider in evaluating a program is its costs. We will discuss cost-efficiency analyses later; for the present let’s consider some types of costs that can be assessed. Perhaps the most obvious source of costs is the monetary cost of administering the program: the number of dollars the funder must lay out to provide the treatment. Although these costs are best assessed by accountants, program evaluation research can investigate a number of factors that can affect them, such as the optimum length of treatment. If a 13-week program has essentially the same effect as a 26-week program, then twice as many clients can be served in a year at the same cost. Another factor affecting the cost of a program is the method of providing treatment. For example, group treatment that is just as effective as individual treatment can be provided at less cost. A third testable cost factor is the required level of professional qualification of the staff. Does effective treatment require staff with doctoral degrees, or will staff with master’s level training or even nonprofessional staff suffice? The higher the technical qualifications of the staff, the more they must be paid and the more the program costs. A number of highly successful programs, such as Alcoholics Anonymous, are run by nonprofessionals.

Programs also entail costs to clients. Some are monetary costs directly related to program participation, such as any fees or deposits the program requires and the cost of transportation to the program site. Other monetary costs are indirect, such as child care costs while a client attends the program. Other costs might be psychological or social in nature, such as lowered self-esteem from perceiving oneself as being in need of help, impolite treatment by program staff, frustrations caused by red tape and understaffing, and disruptions of one’s day-to-day life caused by attending the program. Finally, do not overlook costs to staff, especially in terms of negative side effects of providing services. An understaffed program can quickly result in high levels of stress for the staff, and constantly having to deal with troubled and sometimes frustrating clients can lead to burnout.

Acceptability of the program. A program can be highly effective in terms of bringing about the intended changes, but if potential clients don’t like the program, they will not use it. Similarly, if a program is perceived to be unpleasant to work in, it will be difficult to recruit well-qualified staff. The acceptability of the program to other stakeholders can also affect its viability. Patton (2008), for example, tells of a parenting skills training program for low-income families that was opposed by leaders of welfare rights organizations who perceived it as an unwarranted interference in people’s lives. It is therefore very important for evaluation research to assess the acceptability of a program to all stakeholder groups. Information on sources of dissatisfaction can be used to improve the program, and comparison of two programs that are equally effective on other criteria could find that one is more acceptable, and therefore more likely to be used, than the other. Without utilization, even the best designed program will be a failure.

As we noted at the beginning of this chapter, evaluation researchers can ask four questions about a program. Following Kazdin (2003), we describe these designs in the context of psychotherapy outcome research, but they apply to the evaluation of any type of program.

Is the program effective? This is, of course, the most basic question in program evaluation. It is usually addressed using the program package design in which the program is compared to a no-treatment or waiting-list control group. The concept of “program package” acknowledges that programs are often complex, consisting of several aspects or components that could be investigated separately. However, this strategy ignores those complexities, looking at the effects of the program as a whole. The comparative outcome design is used to compare the effectiveness of two different programs that have the same goals, addressing the question of which program is more effective, and includes a control condition against which to evaluate the effects of both programs. For example, the Klosko et al. (1990) study described earlier compared the effectiveness of psychotherapy and medication as treatment for panic disorder to two control conditions.

What aspects of the program are important? A complex program might have some components that are required for it to be effective and other components that contribute little or nothing to its effectiveness. The dismantling design tests the necessity of including a component in a program by comparing a client group that experiences a version of the program which includes that component to a client group that experiences a version of the program which does not include that component. For example, Nezu and Perri (1989) compared two versions of a social problem-solving treatment for depression—one that consisted of the entire treatment program and one that omitted a component that the theory the treatment was based on postulated was important for success of the treatment—and a waiting-list control group. They found that at the end of treatment, 86% of the people who had experienced the full treatment could be classified as non-depressed, compared to 43% of the people who experienced the partial treatment, and 9% of the members of the group. These results supported the importance of the omitted component of the treatment program.

The client and program variation design addresses issues such as whether a program is equally effective for all client groups or whether it is equally effective if implemented in different ways, such as with professional versus nonprofessional staff. For example, Kadden, Cooney, Getter, and Litt (1989) hypothesized that alcoholics with different levels of psychological impairment would respond better to different types of treatment programs. They postulated that patients with lower degrees of impairment would benefit more from group therapies in which they interacted with each other, whereas patients with greater degrees of impairment would benefit more from coping-skills training that emphasized relapse prevention. Kadden et al. compared high-and low-impairment patients and the two types of treatment in factorial design and found an interaction that supported their hypothesis: The patients who underwent the treatment that the researchers thought was more appropriate to their level of impairment drank less over a 6-month period than the patients who underwent the treatment that the theory suggested would be less appropriate.

How can the program be improved? Even effective programs can sometimes be improved, and two designs can be used to evaluate the effects of program changes. With the constructive design, a component is added to a successful program to determine if the addition will improve goal attainment. In parallel to the dismantling design, a client group exposed to the expanded program is compared to a client group undergoing the standard program; a no-treatment or waiting-list control group can also be included in the design. Rather than varying the content of a program, the parametric design varies the degree to which clients experience a component of the program. For example, a short version of the program might be compared to a long version, or a version in which clients participate three times a week might be compared to one in which clients participate once a week.

How valid is the theory of the program? The validity of the theory underlying a program can be evaluated by any of these designs if the effects of theoretically relevant variables are assessed. For example, theoretically relevant estimator variables can be assessed as part of a treatment package or comparative design to see if they have the mediating effects hypothesized by the theory. Theoretically relevant policy variables can be manipulated in the other four designs, and theoretically relevant client variables can be included in a client variation design. Therefore, the effectiveness of a program and the validity of the theory underlying it can be tested simultaneously in an action research paradigm.

The minimum requirement for an evaluation research study is a 2 × 3 factorial design with a treatment group and a control group assessed on the dependent measures at three points: pretreatment, at the end of treatment, and a follow-up at some time after the end of treatment. The pretest ensures that the treatment and control groups are equivalent at the outset of the research and provides a starting point against which to assess the impact of the program. The follow-up is conducted to determine the extent to which the effects of the program endure over time. Depending on the goals of the research, there can, of course, be more than two groups and additional assessments can be made during treatment and at multiple follow-ups.

Any of the research designs discussed in Chapters 9 through 14 can be used to evaluate a program, but quasi-experimental designs predominate. In a review of reports of 175 published program evaluations, Lipsey, Crosse, Dunkle, Pollard, and Stobart (1985) found that 39% used quasi-experiments, almost all of which were nonequivalent control group designs, 19% used true experiments with program participants randomly assigned to treatment and control groups, and 11% used pre-experimental designs that consisted of a pretest and a posttest of a treatment group but had no control group. The remaining studies were equally divided among qualitative evaluations, studies that had no pretest, and subjective evaluations. This section briefly overviews some of the issues involved in choosing among the various research designs.

True experiments. In principle, the true experiment is the ideal strategy for evaluation research because it can most definitely determine if the program caused any changes that are observed among the program’s clients (Posavac & Carey, 2007; Rossi et al., 2004). However, as Lipsey et al. (1985) found, it is infrequently used for evaluation purposes, perhaps because many practitioners perceive controls used in true experiments, such as random assignment of participants to conditions and control of situational variables, to be impractical to implement under the natural setting conditions in which programs operate (Boruch, 1975). However, as noted in Chapter 10, field experiments are quite often used in research in general and can also be used for program evaluation; Boruch (1975), for example, lists over 200 program evaluations that used experimental designs. In addition, many programs—such as psychotherapy, substance abuse treatment, and educational programs—are carried out in relatively controlled environments such as clinics and schools that are amenable to random assignment of people to conditions and to experimental control over situational variables.

There are, however, also situations that, while offering less control over situational variables, allow random assignment of people to conditions (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002; Posavac & Carey, 2007). For example:

• |

When program resources are scarce and not all potential clients can be served, randomly choosing who enrolls in the program may be the fairest way of allocating the resources because determining who is most in need might be virtually impossible. Consider, for example, the lotteries that some colleges and universities hold to allocate rooms in dormitories for which there are more applicants than spaces. |

• |

Scarce program resources can result in a first-come, first-served approach to allocating resources, and people are put on a waiting list until there is space for them in the program. In such a situation, assignment to treatment or the waiting list might be quasi-random, leading to the use of people on the waiting list as a control group, as in much psychotherapy research. |

• |

Other forms of natural quasi-randomization can also occur, such as when patients admitted to a hospital or other in-patient treatment facility are assigned to wards or other units. Different versions of a program can be instituted in different units and other units used as control groups. |

• |

Sometimes people have no preference among alternative versions of a program and so they essentially give permission to be randomly assigned.In some situations, there is a legitimate power basis for randomly assigning people to conditions, such as when an organization development intervention is conducted. Employers have the authority to make reasonable changes in employee working conditions or procedures and so can randomly assign people to experimental and control conditions of an intervention. |

When planning an evaluation, always be alert to aspects of the program that might allow random assignment of clients to conditions and permit the control extraneous variables. The knowledge about causality gained from a true experiment is usually well worth any inconvenience its use engenders.

Quasi-experiments. The quasi-experiment, especially the nonequivalent control group design, is the most commonly used evaluation research strategy (Lipsey et al., 1985), perhaps because of the ease with which educational, industrial, and similar interventions can use one natural unit, such as a classroom, as a treatment group and another natural unit as a control group. This convenience comes, however, at the cost of not being completely able to rule out preexisting differences between the groups as alternative explanations for the results of the evaluation (see Chapter 10). Another reason for the extensive use of quasi-experiments in evaluation research is that many evaluations are designed and conducted after a program has been instituted rather than being built into the program. Consequently, control groups must be formed after the fact and constructed so that they can be used to rule out alternative explanations for the program’s effect. Cordray (1986) calls these designs patched-up quasi-experiments (see Chapter 10) because the control groups are selected in ways that patch over holes in the internal validity of the research.

Threats to internal validity. Experiments and quasi-experiments are designed to avoid as many of the threats to internal validity discussed in Chapter 7 as possible. However, evaluation researchers must also be sensitive to potential internal validity problems that arise from the nature of evaluation research. A key issue to consider is the composition of the control or comparison group against whom the treatment group’s progress will be assessed. Consider, for example, the case of two evaluations of the same school intervention program for low-income students that came to opposite conclusions about the program’s success (Bowen, 2002). In a discussion of those evaluation studies, Bowen points out that one source of the differing conclusions might have been the composition of the control groups the researchers used. One of the research groups took a quasi-experimental approach with two comparison groups: all the students in the school district who were not enrolled in the program and just the low-income students in the district. However, it turned out that both of these groups differed from the students in the program being evaluated on racial/ethnic group membership, family income, or family background. The other research group took advantage of the fact that there were more eligible applicants for the program than there were spaces available. Because the state law that created the program required that students be randomly selected into the program in such a case, the researchers used the students who had not been selected for the program as their control group. The selection rule mandated by state law had essentially created a true experiment for researchers, with students being randomly assigned to either the treatment group (those selected for the program) and a control group (those not selected). The researchers who conducted the quasi-experiment concluded that the program had had no effect whereas the researchers who conducted the true experiment concluded that the program was successful. Had the first study been the only one conducted, the program would have been deemed a failure.

Additional threats to internal validity of evaluation studies can develop during the course of the program (Shadish et al., 2002). Four of these threats affect only the control group, so their effects are sometimes referred to as control group contamination. One such problem is treatment diffusion: Members of the control group learn about the treatment from members of the treatment group and try to apply the treatment to themselves. For example, while conducting an evaluation of the effectiveness of a Students Against Drunk Driving (SADD) program, Klitzner, Gruenewald, Bamberger, and Rossiter (1994) found that students at one of the control schools had formed their own SADD group. This problem can be avoided in quasi-experiments by using treatment and control groups that are geographically separated and unlikely to communicate, as was done by Greenberg (1990) in his study of the effects of explaining management decisions to employees on employee morale (described in Chapter 10). If treatment diffusion does occur, the “contaminated” control participants can be treated as an additional condition in the study and their outcomes compared to those of the members of the treatment and “pure” control groups.

Another potential problem is attempts by staff to compensate the control group for being deprived of the benefits the treatment group received. For example, Feldman et al. (1983) found that 44% of the members of their control group received some sort of systematic intervention from the program staff. As with treatment diffusion, it may be possible to treat the “contaminated” control participants as an additional condition in the research.

Third, control group members who are aware that they are part of a control group might feel rivalry with the treatment group and work to outdo them on the posttest. For example, in an evaluation of the effects of an employee incentive program on job performance, Petty, Singleton, and Connell (1992) found that managers and employees who were supposed to constitute the control group learned about the experiment and tried to outperform the employees in the treatment group.

A fourth potential problem is the converse of rivalry, resentful demoralization: Members of the control group learn that they are being deprived of a program that could benefit them and so reduce any efforts that might have been making to solve their problem themselves. For example, in a job skills program designed to increase employment, members of the control group might feel that people in the program have an unfair advantage in job hunting and so reduce their own efforts in that direction (Posavac & Carey, 2007). Because most programs are designed to have a greater impact than normal self-help efforts, when members of a control group stop such activities because of their knowledge of their control status, they no longer provide the baseline required for a valid evaluation of the program.

A final threat is local history, which can affect either the control group or the experimental group. Chapter 7 pointed out that history as a threat to internal validity is an event outside the research that affects the dependent variable. Local history is an event that affects only the treatment or only the control group and so is local to it. This threat is strongest in quasi-experiments in which the treatment and control groups are geographically separated. For example, one of Greenberg’s (1990) indicators of employee morale was turnover—the number of employees who quit. If a number of desirable jobs had become available in one of the cities in which the factories participating in his study were located, the factory in that city might have experienced increased turnover regardless of whether it constituted the experimental group or a control group. The effects of this threat can be reduced if the treatment and control groups each consist of several naturally occurring groups, each in a different location: It is unlikely that the same local history event would affect all the sites within a condition.

The members of an evaluation team cannot detect and deal with these threats unless they are familiar with how the treatment is being implemented; how participants, especially control participants, are responding to being part of a study; and what events are occurring in the study environment. Such familiarity can come only through a well-planned process evaluation designed before the program is started.

Pre-experimental designs. Lipsey et al. (1985) found that 11% of their sample of evaluation studies used what Cook and Campbell (1979) refer to as a pre-experimental design, a pretest-posttest design without a control group. Such a design is pre-experimental because without a control group there is no way to assess the impact of the internal validity threats discussed in Chapter 7. Why, then, would anyone use such a design? There are two reasons. First, it is sometimes impossible to come up with a no-treatment control group. For example, the treatment might be made available to all members of the population, comprising what Cook et al. (1975) called a “universally available social good” (p. 22), such as television programming. If everyone is exposed to the treatment, there can be no control group; in such a case, only pretest-posttest comparisons can be made of the treatment group. One can, however, also conduct correlational analyses of the relationship of program variables to outcome variables. For example, in the evaluation of Sesame Street, Cook et al. found that children who watched the program more often scored higher on the outcome measures. Second, Posavac and Carey (2007) suggest that pre-experiments can be used as inexpensive pilot studies to determine if a more expensive full evaluation is necessary. They also suggest that program administrators and staff might be more accepting of an evaluation that does not include a no-treatment group and that positive results from such a study might make administrators and staff more amenable to a more rigorous evaluation.

Although pre-experimental evaluations can be done and are done, they should be avoided if at all possible: The conclusions that can be drawn from their results will be weak and so may not be worth the effort. If a pre-experimental evaluation must be done, then the results must be very carefully interpreted in light of the internal validity threats discussed in Chapter 7 and the limitations of correlational research discussed in Chapter 11.

The single-case strategy. Although Lipsey et al. (1985) did not report finding any evaluations using the single-case approach, such evaluations are frequently used in psychotherapy outcome evaluations (Kazdin, 2003). Single-case experiments may be especially amenable for use in evaluation research because they can be designed to answer any of the four evaluation questions (Hayes & Leonhard, 1991). For example, alternating treatment designs can be used to assess the effectiveness of a treatment, using an A-B-A approach, and treatments can be compared using an A-B-A-C-A design.

Meta-analysis (which we discuss in more detail in the next chapter) is a technique for statistically combining the results of a set of studies that test the same hypothesis. Based on the principle that the average of a set of scores is a more accurate indicator of a true score than any of the individual scores that contribute to the mean, one question that meta-analysis can address is, what is the average effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable across a set of studies? In program evaluation terms, the question becomes, looking across a number of programs that use the same treatment to address the same problem, what is the average effect of that treatment?

For example, Ennett, Tobler, Ringwalt, and Flewelling (1994) examined the average outcome of eight evaluations (all using true or quasi-experimental designs) of Project DARE. DARE (Drug Abuse Resistance Education) is a school-based program taught by police officers designed to prevent drug use (including alcohol and tobacco) among children and early adolescents. The evaluations that Ennett et al. reviewed assessed the program’s effect on six self-report dependent variables: knowledge of drugs, attitudes toward drug use, attitudes toward the police, social skills, self-esteem, and drug use. Ennett et al. found that averaged across the eight evaluations, the DARE program had a modest positive effect on drug knowledge; small positive effects on anti-drug attitudes, social skills, and attitudes toward the police; and essentially no effect on self-esteem or drug use. They also found the DARE program to be less effective than some other types of programs.

Meta-analysis can also estimate the effects of possible moderators of a program’s effectiveness and so assist in identifying the conditions under which a program is more or less effective. Such information can help practitioners to decide whether a particular intervention is appropriate for a particular client group or in a particular setting.

It is not uncommon for an evaluation to find that a program had no effect. Lipsey et al. (1985), for example, found that 37% of the 175 published evaluation studies they reviewed found no program effect. They also noted that this figure is probably an underestimate because of bias against publishing null results. In this section we consider two issues concerning null results in evaluation studies: sources of null results and situations in which null results might not be so null.

Sources of null results. Weiss (1998) noted three sources of null results in evaluation research. The first is program failure, a true null result: The program does not bring about the desired effect. However, before reaching this conclusion, the evaluation team must consider two other sources of null results stemming from Type II errors. One source of Type II error is implementation failure, discussed earlier: Was the program implemented as designed? Did the program have all the resources necessary for its success?

The second source of Type II errors is evaluation failure: poor research. Evaluation research is prone to the same Type II error problems that can affect all research (see Chapter 17). Lipsey et al. (1985) found that low statistical power is a rampant problem; the average power for the studies they reviewed was .28 for a small effect, .63 for a medium effect, and .81 for a large effect. Another common problem is using measures of unknown reliability, validity, and sensitivity (Lipsey et al., 1985). Evaluators must also be sensitive to the content validity of their research: They must be certain to include measures of all the outcomes considered to be important by all stakeholder groups. A program might have effects on some outcomes but not others, and if an outcome is not measured, the evaluation cannot show that the program had an effect on it. Finally, the evaluation must use appropriate operational definitions. For example, one goal of school desegregation is the improvement of interracial relationships. Relationship quality has been assessed in two ways in school desegregation research (Schofield & Whitley, 1983). One operational definition is peer nomination: the number of other-race children whom students name as best friends. The other operational definition is the roster-and rating method: Children rate how much they like each member of their class; these ratings are then averaged by race of the rated children. Peer nomination studies tend to show more racial bias than roster-and-rating studies, but

while cross-racial best friendships may be desirable, they go beyond the degree of interpersonal intimacy which desegregation as a social policy is designed to bring about.… As such, best friendships may not be an appropriate criterion for success in achieving the social goals of school desegregation. (Schofield & Whitley, 1983, p. 249)

When “null” results are not null. The term null results is typically used to mean that there is no difference in outcome between a treatment group and a control group or between two treatment groups, both of which perform better than a control group. However, in the latter case—the relative effectiveness of two treatments—outcome is not the only evaluation criterion. For example, two treatments could have the same level of outcome, but one could be delivered at a lower cost, could achieve its results more quickly, or could be more acceptable to clients or other stakeholders. For example, Bertera and Bertera (1981) compared the effectiveness of two versions of a counseling program for people being treated for high blood pressure. The program’s counselors encouraged participants to take their medication, control their weight, and reduce sodium intake; noncompliance with these aspects of treatment is a major problem in treating hypertension. One version of the program had counselors telephone their clients every three weeks to give the reminders, to answer clients’ questions, and to give other advice as requested; the other version of the program had clients come to a clinic every three weeks for face-to-face counseling sessions. A greater proportion of participants in both versions of the program achieved clinically significant reductions in blood pressure than did members of a no-counseling control group, and the size of the program’s effect was the same for both versions. However, the telephone version cost $39 per improved client compared to $82 per improved client for the face-to-face version. Therefore, do not be too quick to draw conclusions of no difference between treatments without considering non-outcome variables that could have an impact on a decision to continue or terminate a program.

The efficiency analysis stage of program evaluation compares the outcomes produced by a program to the costs required to run the program. Note that efficiency analysis is descriptive: It provides information about costs and outcomes. Efficiency analysis does not address the question of whether the outcomes are worth the cost; that question is a policy or administrative question, not a scientific question. The purpose of program evaluation is to provide policy makers and administrators with the information they need to make such value judgments, not to make the judgments for them. Likewise, the question of the monetary cost of a program is an accounting question, not a psychological question. The determination of the dollar costs is an extremely complex process (Posavac & Carey, 2007; Rossi et al., 2004) and so is best left to accounting professionals. In this section we will briefly examine the two major forms of efficiency analysis, cost-benefit analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis.