The galvanizing event in the recent history of religion in India was the destruction of the so-called Babri Mosque in Ayodhya, a sleepy pilgrimage town on the Gangetic Plain southeast of Delhi. There, on December 6, 1992, Hindu militants pulled down a Mughal mosque stone by stone as two hundred thousand people watched and cheered. They were clearing the ground for a massive temple to Rama on the site they believe to be this god’s birthplace—a site, therefore, where no mosque ever belonged.

The dispute about Rama’s birthplace is a long and intricate one. Many Hindus would date it to the construction of the mosque itself, by a lieutenant of the Mughal emperor Babar in 1528. Why but for the fact that Ayodhya was a major Hindu place of pilgrimage, they say, would this little town have warranted such a grand Muslim edifice? Activists typically go on to claim that a Hindu temple on that exact site was destroyed to make way for the mosque. This claim, plausible enough when one considers the history of other sacred places in India and around the world, has nonetheless been hotly disputed on the basis of the evidence at Ayodhya itself. Academics have weighed in on both sides of the debate.

Turmoils at Ayodhya have had a way of coinciding with major political shifts. Confrontations between groups of Hindus and Muslims shortly preceded the British takeover of that part of India in 1856 and again followed the great anti-British revolt of 1857. About a century later, in 1949, soon after the British had “quit India” and the subcontinent had suffered a bloody partition into the sister states India and Pakistan, an image of Rama suddenly appeared inside the precincts of the mosque. Heralded as a miracle by some and as a hoax by others, this event led to a long moratorium in which the mosque/temple was closed to worship, by court order. When judges opened the doors again in 1986, the struggle intensified, this time primarily under the pressure of a massive campaign waged by the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP, or World Hindu Council), a group with close ties to the major instrument of Hindu nationalism in India today, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

The BJP depicted itself to voters across India and to expatriates around the world as the one force capable of rescuing India from the long-ruling Congress Party’s policies of socialism, unbalanced secularism, slavish submission to the demands of minorities, and general corruption. The BJP portrayed itself as the superior party on two fronts. First, it was clean and efficient—a claim that enjoyed somewhat greater credence before the BJP actually acceded to rule in several states. Second, it was a party with a central agenda, and an agenda about a center. That center was Hinduness (hindutva), a concept it borrowed from Hindu groups who had been active since the early decades of this century. The BJP filled out the concept by giving it a physical focus: it held up Ayodhya as the symbolic center of Hindu life. Ayodhya was depicted as the ideal city, the city where the god Rama had watched over his golden-age kingdom (ram rajya). As the divine exemplar of sovereignty, Rama himself was to be India’s ruler again, with the BJP (and implicitly sister groups such as the VHP) as his chief instruments of power.

The problem as the BJP saw it was that Ayodhya, once a truly sacred center, had been defiled. Its most massive building was now a mosque, a structure representative of a polity and religion that the BJP and VHP depicted as belonging to an invader—politically Mughal, religiously Muslim. The mosque must go if India was to recover the sacred core of its identity. A new temple marking Rama’s birthplace would supplant it. Several times in the 1980s and early 1990s the VHP and BJP mobilized the paraphernalia of pilgrimage to create that sense of center. In a VHP “temple-chariot journey” (rath yatra) that raced through much of India in 1985, trucks replaced the traditional wooden temple carts as conveyances for images of Rama and his consort Sita, who were shown behind bars. Their jailers were the twin forces of antireligious secularity and undue Muslim power over India, and the gods were to be freed in Ayodhya at the end of their sojourn. Their “liberation” (mukti) would be represented by the (re)construction of the Temple of Rama’s Birthplace. In 1989, another set of performances followed, in which bricks were consecrated in local communities all over the subcontinent and abroad, then sent to Ayodhya for inclusion in inaugural ceremonies for the new temple—another great ingathering calculated to sharpen the city’s profile as sacred center. The next year the BJP’s leader, L. K. Advani, performed a 10,000-mile “temple-chariot journey” himself, again with Ayodhya as the destination.

Toward the end of 1990, drama yielded to confrontation as the BJP and its allies sent the first “troops” to attack the mosque itself. Tens of thousands of activists massed, and six of them were killed by police in the fray. Instantly, they became martyrs. From then onward clouds gathered thickly as electoral struggles intensified—there were major BJP victories at the polls in 1991—and at the end of 1992 another major thrust against the mosque was organized. This time hundreds of thousands of militants flooded into Ayodhya, camping in regional groups and often in settings prepared with near-military precision. December 6 was the day announced for attack (“liberation”), and a flurry of last-minute measures involving the provincial and central governments and the judiciary ultimately did nothing to deflect it. To many people’s surprise—and horror—the government failed to intervene in any decisive way. In five hours’ time the mosque came down, its three great domes crashing into a dusty sea of rubble.

Where is all that rubble? On a visit to Ayodhya only a month afterward (January 1993), I could see almost none. True, there was a vast mesa of crushed stones that would soon become a thoroughfare connecting the main highway directly to Rama’s birthplace and eerily avoiding the rest of the town. Ayodhya had been an amiable warren of temples, tombs, and ashrams constructed over the years to express the pieties of many generations of Hindus, Jains, and even Muslims—often with the help of governments captained by Muslims. Now these truckloads of stone had been brought in to bypass all that and lead in a no-nonsense way to the new “tourist park” surrounding the mosque/birthplace that the BJP-controlled state government had vowed to create. Here one saw in graphic terms what someone hoped would be a sleek new Hinduism that could circumvent, cut through, repackage, and obscure the old.

The stones that built that road were new stones. Like most of the BJP and VHP activists themselves, they had been imported into Ayodhya from beyond the city limits, and they bore no physical relation to either the long-lost original temple (if ever it stood there) or the mosque that is said to have supplanted it. These were the stones of Hindu modernity.

A very different kind of stone stood at the site of the erstwhile mosque itself. This bit of rubble was claimed to be truly indigenous and had been raised to the status of an altar. Still there today, it is a segment of a pillar that is said to have emerged from the walls of the Babri Mosque during its destruction. The claim is that the mosque’s builders cannibalized it from an earlier temple that stood on the site until Muslims destroyed it. Despite vigorous denials in important scholarly circles, this and related matters were still being debated two years later, so intensely that the argument disrupted the proceedings of the world archaeological conference held in Delhi in December 1994. There is no way to prove the cannibalization theory from the pillar itself. In the Pala style, with no distinguishing iconography, it could as well have come from a Jain temple as from a Hindu one. That is significant, for there was a time when the Jain presence in Ayodhya was more impressive than the Hindu, although you’d never know it from the rhetoric of Hindu revivalism today.

So much for “Hindu” rubble. But where is the Muslim rubble? Where is the rest of the mosque? Some say the vast Hindu crowd took it away piece by piece, as souvenirs and objects of veneration. This sounds plausible. The cause of Rama would have transvalued these infidel stones into holy relics, and pilgrims are notorious for dispersing such sacra. Yet many of the blocks that made the mosque were reputedly enormous. Where did they go?

One answer was offered by a judge whom I met in Ayodhya in early 1993. Recently retired from the Lucknow branch of the provincial High Court, he had come with a high police officer to worship in one of Ayodhya’s many temples. He explained that the disappearance of the great stones was—well—inexplicable. Referring to the monkey god who is Rama’s greatest devotee and the very image of strength and speed, he said, “It was all Hanuman’s miracle. For a huge mosque like that to come down in a few hours—with tridents and pickaxes! And now no trace! What can it be but Hanuman’s miracle?”

Perhaps we should not be surprised to find a well-educated, English-speaking judge invoking the miraculous. We have already alluded to the Lucknow court’s role in the Ayodhya controversy, and a full account would make for a pained and convoluted story. It would be understandable if the judge hoped, in some corner of his consciousness, that this record might helpfully be set straight by the intervening hand of God.

Nor should we be surprised to find a high-ranking police officer at prayer beside him. In that part of India, the force has been overwhelmingly Hindu by design since shortly after independence, and by everyone’s account it played a major part in allowing the mosque to be destroyed. Although the commanding officer tried to protect the mosque, others apparently gave the demonstrators an hour to demolish it, then extended the deadline when the task proved more formidable than had first been imagined. Several retired police officers, along with a group of civil engineers, were involved in the demolition itself. They organized the younger volunteers, showing them, for example, how to dismantle the mosque’s protective railing and use the segments as battering rams.

How could they not be involved? From their point of view, they weren’t creating rubble; they were clearing, consolidating, building! There was a definite sense throughout Hindu Ayodhya that such workers were part of something to be proud of—something large and unitary for a change, the wave of a coherent future, something clean and right. Something sanctified by the blood of martyrs, too. Many pages in the ubiquitous little souvenir books about Ayodhya are taken up with gory photographs of the six young men who died when police were ordered to repulse the 1990 assault on the mosque. Oddly, the precedent for such books of martyrs comes from the Sikhs, as does the term invariably used to designate Hindu activist volunteers, kar sevak. Even more striking, the word used to name the martyrs themselves, shahid, comes from Islam. (See figure N at the Web site http://www.clas.ufl.edu/users/vasu/loh.)

In the West there is a deep-seated belief that the rubble of Ayodhya and places like it is caused by pulling the pillars out from under the temple of modern secularism. This is a new version of the colonial view “If we go, they’ll kill each other.” (That prophecy fulfilled itself all too easily in the months following independence in 1947.) Hindus in Ayodhya see it the other way around. The mosque was a symbol of desecrating foreign rule, a long colonial past. It was also tied up with the self-proclaimedly secular Congress Party government that inherited the British mantle in New Delhi and helped preserve its hold on power by projecting itself as the protector of Muslims in exchange for their support on election day.

So the confrontation at Ayodhya was not just Hindus versus Muslims, but Hindus versus secularists as well. As one man put it, using an English word in a Hindi sentence, it was the “unqualifieds” standing up against the English-educated “qualifieds” who get all the good jobs, especially in government. Self-made men like himself (he owned his own taxi) were pulling down the massive rubble of a bureaucratized, colonial past. A vivid wall painting showed Prime Minister Narasimha Rao sweating bullets and crying, in Hindi, “Save my government!” My government—not just “my” of the Congress Party, but of all those complacent, self-interested “qualifieds.”

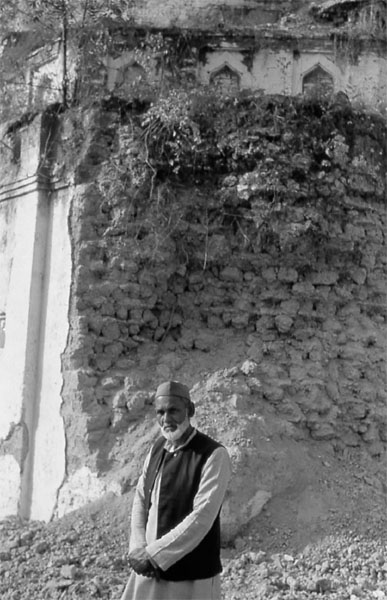

Marx is surely turning over in his grave to find that religion provides the language of anticolonial struggle in much of the world today. Some opiate! But as the temple of postcolonial secularism is attacked, so also are real temples—or, in this case, mosques and tombs. On the outskirts of Ayodhya stands the tomb of a Muslim saint that has served as a focus of worship for centuries. On December 6, 1992, after the Babri Mosque came down, one part of the great visiting mob set upon this tomb too, destroying the saint’s grave and dislodging many bricks from the walls (see figure 11). “Most of the people who worship here are Hindus,” reported an immaculate, soft-spoken local Muslim leader whom I encountered there. “We have always lived together in peace. Whatever happened downtown, we never thought it would come here. Yet. . . .”

Here is rubble of another kind—neither the rubble of the imperialist incursion that the Babri Mosque represented to many Hindus nor the simple product of age-old Hindu-Muslim rivalries, as secularists sometimes like to think. This is rubble created by a newly streamlined brand of Hinduism. One can perhaps sympathize with the desire to remove a mosque built by a religious culture aggressive enough to raze many Hindu temples, possibly including one that stood on the site of the Babri Mosque itself, as alleged. But here the crowds were erasing from memory a symbol of the fact that Hindus and Muslims have so often prayed together. This unruly mix is one of the glories of India, giving the lie to all those airtight textbook chapters on Hinduism, then Islam. Such a tradition is more than tolerance: it’s life together, unbrokered by secularism or any other mediating ideology.

Ayodhya is being reshaped by a new kind of Hinduism: a syndicated, textbook Hinduism that offers a new sense of political agency to many in the majority who have so far felt left out. As this new Hinduism takes hold, the tomb of Sisle Hazrat Islam and all it stands for is in danger. So is the intricate network of arrangements symbolized in the ashrams and temples of the old Ayodhya, as a great road is bulldozed from the edge of town to the as-yet unbuilt Temple of Rama’s Birthplace.

And what about the rubble, the huge stones that once were the great building-blocks of Babar’s Mosque and are now, in their absence, the stuff of miracles? Where did they go? There are some good-sized rocks lying near the place where the mosque once stood, but nothing to rival what visitors would see if they visited the great Mughal mosques that have so altered the landscape of great Hindu cities such as Mathura and Benares.

The answer, as it turns out, is quite simple. The mosque was not actually constructed of such stones. It predated the fine mosques of Mathura and Benares and used a more modest medium: large bricks of the Jaunpuri style. So the miracle of the stones, as proclaimed by the justice from Lucknow, was a miracle in his mind.

FIGURE 11

“Most of the people who worship here are Hindus”: Muslim leader surveying the wreckage of the tomb of Sisle Hazrat Islam, Ayodhya, January 2003. Photo by John Hawley.

And its major predecessor is little different. For years Hindu enthusiasts have spoken as if the image of the child Rama that was discovered in the Babri Mosque on the morning of December 23, 1949, got there as a result of divine intervention in the affairs of this world. After all, some of the most important images in Hindu temples throughout India are said to be svayambhu—self-manifested. For the child Rama of Ayodhya, that may still be so in a symbolic sense, but we now know that it is not true in a literal one. Recently, after decades of public silence, an ascetic living in Ayodhya has confessed that he and several comrades were responsible for placing the image inside the mosque during that night in 1949. The man says it was easier to let people surmise that this was a miracle than to explain the facts, because if they had done so, they would have been prosecuted. They saw their mission as above the courts, whose actions would only have confused matters. In their eyes, that mosque was a temple, since the place on which it was built was Rama’s birthplace. It deserved to be restored to its intrinsic glory—and to its proper owner, Rama.

The crowds who filled the streets of Ayodhya in late 1992 said similar things in the graffiti art with which they covered the walls. “It isn’t a question of justice,” one placard said. “It’s a question that goes beyond the boundaries of the courts. The issue of Lord Rama’s birthplace is not a subject for the courts!” The reason for this, as another poster made clear, is that in the minds of at least some Hindus there is a court above the courts, a true state that defines what statecraft really is. In this poster the young Rama appears as an archer ready to put his arrow to its bow. The caption reads, “The love of Rama is the strength of the state.”

Since 1993, for a variety of reasons, the rhetoric of the BJP has slowly shifted away from the idiom of religious triumphalism. Many Indians have breathed a sigh of relief. Yet the ability of the Congress Party to shepherd the country through a period of fundamental redefinition is still in doubt, and the economic and ideological power of Islamic states not far away continues to rankle an Indian (and, still more, a Hindu) sense of dignity. Then too, the issue of what will be constructed on the site of “Rama’s birthplace” remains unsettled.

In such circumstances it is hard to predict the future of religious nationalism in India, but with the BJP regularly garnering about a third of the vote in elections throughout North India, and with the Congress weakened in the south, it does not seem that it will go away. The Temple of Rama’s Birthplace is still invisible to the eyes of most who travel to Ayodhya, except as a canopy spread across the area where the sacred pillar and the image of child Rama are displayed for pilgrims’ veneration. Yet thanks partially to Ramanand Sagar’s Ramayan, the long-running television series about Rama’s life that was seen at least in part by most of the Indian populace, the image of Rama’s eternal palace in an ideal Ayodhya is shared in a way it has never quite been before.

Many who soaked in the TV “Ramayana”—Muslims among them—cringe at the idea of trying to play it out against the landscape of Indian politics today. But for some, Ayodhya and places like it are the natural theater where “Hindu sentiments,” purportedly wounded for centuries, can be healed. How large a group is this, and can they succeed in persuading others to join their cause in a sustained way? Only time will tell.

This essay was previously published as “Ayodhya and the Momentum of Hindu Nationalism,” based on a version that appeared in SIPA News, Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs, Spring 1993, 17–21.