Chapter 4

“All Rise”: The American Judicial System

IN THIS CHAPTER

Understanding the significance of legal precedence

Understanding the significance of legal precedence

Reviewing the three branches of the U.S. system of government

Reviewing the three branches of the U.S. system of government

Identifying the various forms and levels of government and their courts

Identifying the various forms and levels of government and their courts

Grasping the important differences between trial by judge and trial by jury

Grasping the important differences between trial by judge and trial by jury

The study and practice of paralegalism is exciting because the law reflects society’s changing modes of conduct. So, the law has to be flexible and evolve with society. Despite its flexibility, however, the law has specific theoretical and historical origins, and before studying paralegalism, it’s good to know the theoretical and historical context from which the U.S. legal system has evolved.

To become a good paralegal and understand the basis of your daily responsibilities, you need to be familiar with these background concepts of the U.S. legal system. Spend a little time getting acquainted with the configuration of the U.S. government, the different levels and types of its courts, and the way these courts are set up.

Everything Old Is New Again: The Importance of Legal Precedence

Law is relatively easy to study and understand, because most of the issues that crop up in court every day have been decided in previous trials. U.S. law didn’t materialize overnight. Our legal system has been around for a long time, but it’s also constantly evolving. The U.S. system of justice is based upon the doctrine of stare decisis (pronounced stare-y di-sigh-sis), which means that past court decisions (known as precedent) largely determine the outcome of future cases. As long as the facts and issues of a precedent case are pretty much the same as those of the current case, and as long as the court that rendered (made) the decision in the precedent case is within the same system as and higher than the present court, the present court must adhere to the decision of the precedent case as authority in rendering its decision. (Say that ten times fast.)

In other words, say the U.S. Supreme Court says that police have to advise suspects of their rights whenever the suspects are taken into custody. The doctrine of stare decisis says that this rule will be followed in any other court that considers the same issue in a criminal case. That’s because all other courts in the United States, whether state courts or federal courts, are lower than the Supreme Court. They essentially have to rule as the Supreme Court did.

Stare decisis consists of statutory law and prior case decisions and provides paralegals, attorneys, and judges with security, certainty, and predictability in researching the law. The paralegal’s goal is to find the most applicable case precedent (case law) and statutes, integrate that authority into a memorandum of law (a brief), and present that memo or brief to the supervising attorney. (For more on a paralegal’s duties in the trial process, check out Chapter 14.) The attorney then argues the applicability of that particular stare decisis to the court.

The vast majority of cases that you’ll research are based upon facts and issues that have already been decided. Public policy has already been set. However, as society’s modes of conduct change, so do laws. So, there are times when you’ll find very little, or no, stare decisis for a case because of the uniqueness of that case’s facts and issues.

For example, as of the early 1950s, the law in 17 states and the District of Columbia allowed racial segregation in school facilities. Among the precedent cases interpreted to permit segregation was Plessy v. Ferguson, where the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a Louisiana statute that provided that “separate but equal” accommodations in railroad cars was constitutional. The stare decisis at that time favored segregation, and there was no precedent favoring school integration.

When Thurgood Marshall and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) argued to the Supreme Court in 1952 that the separate but equal doctrine was unconstitutional, they had very little legal precedent to support their position and had to rely on sociological and psychological data to advance the cause of integration. On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court rendered its decision in the watershed case of Brown v. Board of Education, where the Court held that the separate but equal doctrine had no place in public education and that separate but equal educational facilities were inherently dissimilar. New evidence won out over past judicial precedence.

Although the vast majority of cases are rooted in stare decisis, a few occasions arise when precedent is nonexistent. A case of first impression is one where there is no prior precedent or stare decisis to guide the court in its decision making. In these cases, the courts really have to scratch their collective heads to come up with what the law should be. Courts often resolve cases of first impression on the basis of nonlegal traditions, which consequently forms the foundation for future precedent.

Checks and Balances: Branches of U.S. Government

- Legislative branch: The legislative branch makes the laws.

- Executive branch: The executive branch enforces the laws.

- Judicial branch: The judicial branch interprets the laws.

Each of these branches has its own function, and each branch of government provides checks and balances on the other branches so that no one branch of government becomes too powerful. The country’s Founding Fathers feared the power of the kings of Europe and even the Parliament’s stranglehold over England. As a result, no single branch of government in the United States can control the country without running up against another branch.

The three branches of government show up in the federal (national) government and in state governments. Dividing power between the federal government and the state governments is known as federalism. The national and state governments all have their own forms of legal sovereignty (or power) over what happens in society. For example, only the federal government has the power to mint money or declare war. States, on the other hand, regulate such things as driver’s licenses, car registrations, marriages, and divorces. And both the national and state governments have authority over criminal conduct. States can outlaw crimes that occur within their borders, while the federal government can prosecute these same crimes that cross state boundaries (that is, if the crime affects interstate commerce).

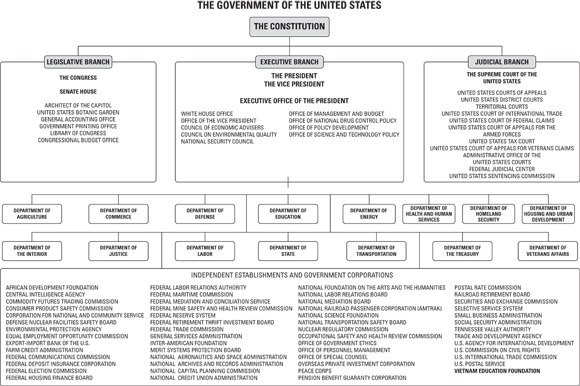

Figure 4-1 shows a complete listing of all three branches of the federal government, including the major administrative agencies. As you can see, administrative bodies tend to get lumped under the executive branch, which is by far the most widespread and bureaucratic of the three branches.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 4-1: Branches of the federal government.

The rule makers: The legislative branch

At the federal or national level, the legislative branch is called the Congress. It’s made up of two chambers — the Senate and the House of Representatives. Sometimes, members of the House of Representatives are called congresspersons, while members of the Senate are called, not surprisingly, senators. Because it has two chambers, the legislature is called bicameral (bi means “two” and camera means “chamber”). The U.S. Congress and every state but Louisiana have bicameral legislatures. The legislatures at both the federal and state levels create statutory law, the rules and regulations we all have to follow to avoid liability or arrest.

To enact a statute, the bicameral legislature must pass a proposed bill through both the House and the Senate and then send it to be signed by the executive branch, which is the president on the federal level or the governor on the state level. Getting a bill through both houses of the legislature and getting it signed by the president or governor is a lot of work! The bill gets introduced in each house and is referred to a committee that considers its particular subject matter. If it’s a bill that has to do with the courts, then it likely gets sent to the judiciary committee in each chamber. The committee might hold hearings, and if the committee chair or the committee doesn’t like the bill, it can die there. If the bill gets changed in either house, then a conference committee in both houses gets together and tries to iron out any differences.

After the bill passes out of both chambers in substantially the same form, the chief executive signs it into law. This means that the president signs those bills that come out of the Congress, and the governor signs those bills enacted by the state legislature. After it’s signed, the bill becomes statutory law. If the chief executive vetoes the bill, the bill dies unless the legislature can muster enough votes to get a supermajority to override the executive branch’s veto. Usually, that means that two-thirds of each house has to vote in favor to override the veto. (This kind of situation is one example of how the legislative and executive branches act as checks and balances on each other.)

A statute is sometimes called an act, such as the Freedom of Information Act or the Federal Communications Act. Given all the hassle that’s required to enact legislation, the expression that “It’s going to take an act of Congress to get that done” makes a lot of sense. Enacting even simple legislation is, in many cases, an uphill battle.

The state legislatures follow pretty much the same procedure the federal government does when enacting legislation. You can find a super-simple illustration of how a typical bill becomes law at www.usa.gov/how-laws-are-made.

The enforcers: The executive branch

In addition to signing bills into law, the executive branch also enforces the laws enacted by the legislature. The president or the state governor obviously can’t accomplish the task of enforcement alone. Consequently, the legislature has created a multitude of administrative agencies that are empowered to assist the chief executive in the role of enforcing and administering the laws created by the legislature.

You may have heard the term alphabet soup to refer to the names of administrative agencies (for example, HUD, EPA, DEA, CIA). Administrative agencies exist on the federal, state, and local levels of government. They’re often referred to collectively as the bureaucracy. Examples of state agencies are the Transportation Department that builds state highways and the Department of Licensing that provides licenses for your car as well as your doctor (the names of these agencies vary from state to state). Some common examples of local administrative agencies are your community’s fire department, the city police department, and the county sheriff’s office.

Administrative agencies also have some legislative power, and they can create the law in certain instances. Often, the statute that creates these agencies and empowers them to enforce laws also enables the agencies to regulate the public. Agencies exert their control through the process of administrative rulemaking, and the laws these agencies write are called administrative regulations. For example, the IRS was created to implement the tax code. If Larry has a problem with his federal income taxes, he contacts the IRS. Larry can appeal his case in the court system only after the IRS renders an administrative determination about Larry’s problem. He would have to exhaust administrative remedies before he could take his case to federal court.

Administrative agencies may even act like courts when they engage in quasijudicial proceedings known as adjudicatory hearings. In adjudicatory hearings, the agencies make decisions that affect the rights of individuals, much like a court of law. (You can find more information about administrative agencies and administrative law in Chapter 5.)

The interpreters: The judicial branch

The court system stems from the third branch of government, the judicial branch. The duty of the judicial branch is to interpret the laws that the other two branches of government create and enforce. When courts interpret the statutes enacted by the legislature, it’s sometimes said that the courts actually make law. This judge-made law appears in the form of judicial opinions.

As intended by our founders, the judicial branch acts as a check and balance on the other two branches of government. One example of the judiciary’s power over the legislature occurs when a court declares a statute unconstitutional. The statute then has to be thrown out and becomes unenforceable. But don’t feel too sorry for the legislature — it can place a check on the courts by enacting a statute that says that courts don’t have the authority to hear specific types of cases. Courts may not be completely stripped of their judicial authority, but their jurisdiction (their power and authority to hear a particular type of case) can be narrowed to a significant degree. Historically, Congress has tried to find ways to narrow the jurisdiction of the federal courts in this manner. One recent example involves proposals to strip federal courts of their ability to decide cases dealing with abortion. The president can also act as a check and balance on the courts by refusing to enforce the court’s orders.

Because most paralegals deal with the judicial branch more than the other two branches, you should become very familiar with the structure of the U.S. court system.

Playing Fair: Levels of the U.S. Judicial System

Each of the three branches exists in the three levels of U.S. government. Each of the levels of government — federal, state, and local — has an executive branch, a legislative branch, and a judicial branch. As a paralegal, you’ll be working primarily within the judicial branch.

The United States employs a unique blend of federal, state, and local court systems to get its judicial work done. Each court system is a separate entity, but they work together to form the case law that attorneys and paralegals rely on to develop their cases. Depending on your area of practice or interest, one level of courts may be more relevant to you than another.

The federal judicial system

The types of cases that may be heard in the federal court are limited. They must meet one of these qualifications:

- Controversies that involve the U.S. government, the U.S. Constitution, or federal laws: This is called the federal question jurisdiction.

- Disputes between two different states or between the United States and a foreign government.

- Cases that involve diversity of citizenship of the litigants: Diversity of citizenship means that the disputes are either between parties from different states or between a party from the United States and someone from a foreign country, and the amount of damages must exceed the amount set forth in federal statutes.

- Matters that involve bankruptcy.

If you work with the federal court system, you’ll deal with three levels of adjudication: the courts of original jurisdiction, the courts of appellate jurisdiction, and the courts of last resort. Federal cases originate in the U.S. District Courts.

In the beginning: Courts of original jurisdiction

The U.S. District Courts comprise the federal courts of original jurisdiction. These courts are geographically situated throughout the country, in Washington, D.C., and in the territories of the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Virgin Islands. There’s at least one federal district court in every state and territory of the United States. Federal district courts have a large caseload because they happen to be located where a significant amount of federal litigation begins. The U.S. Constitution requires that federal judges be appointed for life and that their pay can’t be reduced while they’re in office. This is just one more check and balance against the president and Congress so that federal courts can’t be completely stripped of their authority.

Federal litigation that doesn’t begin in the U.S. District Courts originates in the specialized courts of original jurisdiction: the U.S. Court of International Trade, the U.S. Tax Court, the U.S. Bankruptcy Court, and the U.S. Court of Claims. Because these courts are highly specialized, you’ll find that, depending on your area of practice, you’ll either spend almost all your time working with one of these types of courts or you’ll spend none of your time there. If you choose to specialize and become an expert in federal court matters, you’ll need to gain a thorough understanding of federal court jurisdiction and other federal matters. (We explain how to research federal court matters in Chapter 13.)

The U.S. Supreme Court, affectionately known as “the highest court in the land,” also has original jurisdiction in all cases involving ambassadors, consuls, and public ministers and in all cases where a state is a party. The Supreme Court must have original jurisdiction in those cases where one state sues another state, like the late-1990s dispute between New York and New Jersey (see the nearby sidebar, “New Jersey v. New York: Who’s got the dirt on Ellis Island?”).

Very appealing: Courts of appellate jurisdiction

If you don’t like the result of your trial in the U.S. District Courts or one of the many specialized courts, you can appeal your case to the U.S. Courts of Appeals, which is comprised of 13 units of jurisdiction called circuits. Circuits 1 through 11 are numbered and regionally arranged; the other two circuits are the D.C. Circuit and the Federal Circuit, both located in the nation’s capital. The first appeal from the U.S. District Courts is heard at the circuit court (or U.S. Courts of Appeals) level.

The final chance: Courts of last resort

In the United States, the court of last resort is the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court provides final review on appeal of any case that emanates from the U.S. Courts of Appeals. The Supreme Court may also review decisions appealed from each state’s supreme court.

The U.S. Supreme Court has a somewhat temperamental view of what cases it chooses to hear, however. In fact, the Supreme Court receives about 8,000 petitions for review every year and hears arguments on perhaps only about a hundred of those appeals. The Court selects the cases it wants to hear from the circuit courts or the state supreme courts.

Historically, the Court has levied a great amount of discretion in deciding which cases to hear. Sometimes, it takes cases because the justices want to rule on a topical controversial issue. Or, the U.S. Supreme Court reconciles conflicting decisions from among differing jurisdictions on questions of how to interpret federal law.

Here’s an example: Suppose the Congress passes a law that outlaws burning the American flag, and a New Yorker faces trial in the U.S. district court for the District of New York for breaking this law. Then, suppose that the court of appeals for the Second Circuit Western District of New York rules that a person can be prosecuted for flag burning, but a conflicting Ninth Circuit decision holds that enforcing this law is unconstitutional because it violates the First Amendment’s guarantee to free speech. A person could get away with flag burning in the nine states way out west (as well as in Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands), but the federal government could throw the book at the same person for burning the flag in Connecticut, Vermont, or New York. To have uniformity among the same federal laws throughout the United States, the Supreme Court could accept an appeal from the Second Circuit court of appeals in order to resolve this conflict among the circuits.

State judicial system

State courts handle specific types of cases. Here are just some of the matters that state courts hear from their citizenry:

- Almost all divorce and child custody cases

- Probate and inheritance matters

- Contract disputes

- Traffic violations

- Real estate issues

- Juvenile matters

- Personal injury suits

- Criminal cases

- Matters involving diversity of citizenship with potential damages less than the jurisdictional threshold, which changes frequently

In many states, the court structure looks pretty much like that of the federal system. Apparently, it was much easier for our founders to copy the federal system than it was to come up with something different after the new nation was created. States have courts with original jurisdiction, intermediate appellate courts, and courts of last resort. However, in about half the states, there’s only one level of appeals. In those states, the trial court decision is appealed directly to the highest court in the state, in most (but not all) cases known as the state supreme court.

Initiation: State trial courts

The trial courts in state judicial systems have original jurisdiction over a myriad of cases that come before them, and these cases come in many flavors. Quite often, state trial courts are two-tiered. The lower level of state trial courts often decide civil cases involving money below a certain dollar amount as well as lower-grade criminal cases known as misdemeanors. The lower-level state trial courts are called courts of limited jurisdiction. Depending on the state, these lower courts might be known as county courts, district courts, justices of the peace, or any number of other different names to signify their status as a lower-tiered court. These lower-level state courts have far greater caseloads than any of the higher-tiered courts. Procedures are also generally less formal in these lower-tiered courts. For this reason, a court of limited jurisdiction is often referred to as the people’s court.

The upper-tiered courts at the state level are courts of general jurisdiction, and they similarly have many different names to signify their status. Often, these courts are referred to as the superior courts, state courts, circuit courts, or a variety of other names. Interestingly enough, in the state of New York, the upper-tiered trial court is called the supreme court. The cases heard by upper-tier state trial courts involve anything from criminal felony prosecutions to civil matters where unlimited amounts of money are at issue. These upper-level state courts may also hear appeals from the state’s inferior courts of limited jurisdiction.

Hear it again: Intermediate courts of appeals and courts of last resort

About half of our 50 states have intermediate courts of appeals. These intermediate appellate courts compare to the U.S. Courts of Appeals for the various circuits in the federal system. Like the federal appellate courts, the intermediate courts of appeals in states generally hear matters appealed from the trial courts within their geographical region. So, they might hear only those cases appealed from the trial courts of certain counties located within their region, while another division of the same intermediate court of appeals located elsewhere in the state would hear appeals from counties in its own particular region.

Parties who don’t like the outcome of their trials can file their appeals with one of these intermediate appellate courts as a matter of right. This means that a person has an absolute right to have a higher court review his appeal from the lower court. After an intermediate court hears a case on appeal, the appealing party generally can’t appeal any farther up the chain unless the next higher court grants a request for review. This type of appeal is called discretionary review, where the higher court has discretion as to whether it will even hear the case. In states that don’t have intermediate appellate courts, the losing party can appeal from the trial court of general jurisdiction directly to the state supreme court as a matter of right.

One aspect of appeals that losing parties don’t like to hear about is that an appellant, or losing party, generally doesn’t get to have the case heard all over again. The appellate court’s duty is to decide issues of errors of law that the appellant argues were made by the lower court. The appellate court can overturn the lower court usually only if the inferior court made an error of law, such as a mistake on the admissibility of evidence. This differs from a trial de novo, where in some cases, the trial can be heard all over again at the appellate level. If the trial judge (or jury) chooses to believe one party’s witnesses over the other party’s witnesses, then usually the losing party is out of luck and doesn’t get to have the appellate court second-guess the lower court’s decision based on the credibility of witnesses. The appellate courts don’t get to re-decide the facts of the case.

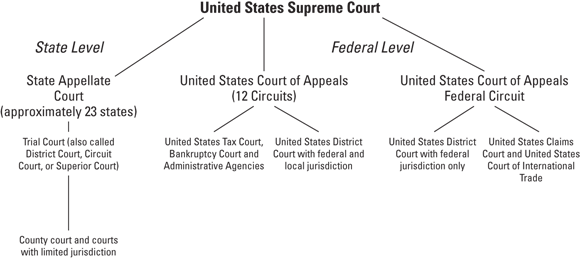

With some exceptions, an appeal from the highest court in a state may be heard by the U.S. Supreme Court. To help you keep it all straight, Figure 4-2 diagrams the general federal and state judicial systems, where you can study the court’s hierarchy.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 4-2: The federal and state judicial systems.

Local judicial systems

Local court systems are similar in many ways to the lower-tiered state courts. Depending on the state, these courts are sometimes called city courts, municipal courts, town courts, village courts, or some other name to indicate their status as the local court system. Local courts generally have jurisdiction or authority to hear only those violations of the laws of cities, towns, or counties. Laws passed by local legislative bodies are called ordinances. Ordinances are analogous to the statutes enacted at the state and federal level, but ordinances only affect the conduct of citizens located within the boundaries of the local government.

Generally, all local-level criminal cases are petty or misdemeanor offenses. States retain exclusive authority to prosecute state felony violations, and local governments share the prosecution of misdemeanor offenses like drunk driving and shoplifting that occur within the local government’s boundaries. Local governments usually prosecute violations of zoning ordinances or building codes because these matters are nearly always matters of local concern. Local courts may also enforce local traffic regulations that occur within the city, town, or county limits.

The loser in a case that starts in the local judicial system usually has an appeal as a matter of right to the next court level. This usually means that the appellant can take his case to the court of general jurisdiction in the state court system. To appeal the case any higher in the system, the party generally has to seek discretionary review from the higher court. The loser at the lower court may be stuck with the lower court’s original decision. This often happens with a plaintiff who loses in a small claims court, which handles matters involving small money damages (which could be anywhere from $1,000 to $100,000 depending on the municipality).

Judge and Jury: The U.S. Jury System

One of the more important and unique attributes of the U.S. system of justice is the jury system. Under the Constitution, persons accused of crimes have an absolute right to trial by jury. Parties to civil suits may choose to have their cases heard by a jury, or a judge only. As a paralegal, you may assist your supervising attorney in deciding whether a client’s case should be decided by a jury or just a judge. This decision can depend just as often on the type of case being heard as on which judge is assigned to hear the case.

At trial, the functions of the jury and judge are significantly different. A judge decides issues of law, such as how a statute or ordinance should be properly interpreted and applied. A jury, on the other hand, has the duty of deciding questions of fact, such as whether a party to a lawsuit acted reasonably in proceeding through a yellow caution light. The jury is required to follow the law, but sometimes juries ignore the law that the judge set forth. This situation is known as jury nullification, where the jury in essence nullifies the law the court presents. Jury nullification often happens when the jurors feel that a law is unjust or is being applied unfairly in the particular circumstances of the current case.

Order in the court: The bench trial

Although most trial court cases in the United States — especially criminal matters — are decided by a jury with a judge presiding over the case, some of the cases are more effectively argued to a judge without a jury. In cases where the right to a jury is waived, the judge decides both the issues of law and the issues of fact. A trial by a judge alone is also known as a bench trial.

Usually, an attorney requests a bench trial in cases, like complex contract disputes, where the facts are pretty straightforward but the law is complicated. For these cases, the parties need a judge to interpret complex law and determine whether someone breached the law.

Other reasons for requesting a bench trial concern time and money. As you might imagine, a jury trial takes much longer to conduct than a bench trial, sometimes as much as 40 percent longer! The trial backlog in the U.S. justice system is generally much greater for jury trials than bench trials, and jury trials cost more to conduct. The loser in a lawsuit usually ends up paying the opponent’s court costs by law in most cases. But often, neither of the parties recoup what they spend on legal fees, and the longer the trial, the greater the fees! (There are two notable exceptions to this general rule: When a law provides for payment of legal fees to the winning party, such as lawsuits involving civil rights violations, or in contract cases where the contract itself has language that specifies that the losing party must pay reasonable attorney fees and costs to the prevailing party.)

Petition to your peers: The jury trial

Worldwide, approximately 95 percent of all jury trials take place in the United States. Many paralegals who have served as jurors express the same feelings of pride and satisfaction articulated by others who have been involved in the jury system. Participating in the jury process is an unequaled lesson in democracy, and if you haven’t served on a jury, you should plan to sit through a jury trial or two to get some firsthand knowledge about judicial procedure.

In most states and counties, jurors are chosen at random from several different computerized lists, like voter registrations, motor vehicle registrations, driver’s license records, and property tax rolls.

The jury’s responsibility is to sort through the facts presented by both sides at trial and decide what’s true and what’s not. A jury determines things like whether a witness is credible or not. It then renders a verdict based on its decision.

In most state criminal trials, juries have to unanimously agree on whether the accused is guilty. The prosecutor, or district attorney or attorney general, must present enough evidence to the members of the jury to convince them that the accused committed the crime charged beyond a reasonable doubt. So, every juror (all 6 or 12, depending on the trial) must agree beyond a reasonable doubt with the verdict of guilty. If they don’t, the accused is deemed to be innocent. In death penalty cases, the jury’s sentencing recommendation also has to be unanimous. In a civil case, the burden of proof is usually by a preponderance of the evidence, meaning that plaintiffs must convince the jury (or judge in a bench trial) that it’s “more likely than not” that their version of the facts is true.

Either the plaintiff or the defendant may request a jury. If the plaintiff doesn’t file a jury demand and include the required jury fee, the defendant may do it. In any case, a jury request is rarely granted if it’s not made before, or shortly after, the close of pleadings. In other words, a jury demand usually must be filed no later than ten days after service of the last pleading.

Attorneys often consult with paralegals about whether to try a civil case to a jury or just a judge. The tactical decision of whether to argue a civil action to a jury is among the more important decisions to be made in the litigation process.

Law has two main interpretations: One is based on the concept of natural (or God-made) law, and the other is a secular (or nonreligious) interpretation. The more ancient of the two interpretations is Aristotle’s cosmic law theory. Aristotle believed that there was a law inherent in the universe that was more important than the laws made by people. In contrast, the more recent secular, or common law, theory holds that law develops from the history of a nation and that legal experts only interpret the historical drift of a nation.

Law has two main interpretations: One is based on the concept of natural (or God-made) law, and the other is a secular (or nonreligious) interpretation. The more ancient of the two interpretations is Aristotle’s cosmic law theory. Aristotle believed that there was a law inherent in the universe that was more important than the laws made by people. In contrast, the more recent secular, or common law, theory holds that law develops from the history of a nation and that legal experts only interpret the historical drift of a nation. Although there are two fundamental bases of the law, U.S. society is most firmly grounded in the secular, or common, law. This law is the kind that’s created by court decisions, which we discuss in more detail in the following section.

Although there are two fundamental bases of the law, U.S. society is most firmly grounded in the secular, or common, law. This law is the kind that’s created by court decisions, which we discuss in more detail in the following section. To understand the U.S. legal process, you need to know about the structure of the U.S. government. As you probably learned in high school U.S. history class, the United States operates under three branches of government:

To understand the U.S. legal process, you need to know about the structure of the U.S. government. As you probably learned in high school U.S. history class, the United States operates under three branches of government:  A statute isn’t some giant structure standing with a torch on Liberty Island in New York Harbor. It’s a law that is written by the legislative branch of government. So be careful in your legal writing because lawyers and paralegals commonly refer to statutes as statues when writing briefs that refer to statutory law. Another common spelling mistake is mixing up the words trial and trail. Although a trial is a journey, you can’t refer to it as a trail. Your spell checker won’t catch these mistakes, either. (You can find more tips about legal writing in

A statute isn’t some giant structure standing with a torch on Liberty Island in New York Harbor. It’s a law that is written by the legislative branch of government. So be careful in your legal writing because lawyers and paralegals commonly refer to statutes as statues when writing briefs that refer to statutory law. Another common spelling mistake is mixing up the words trial and trail. Although a trial is a journey, you can’t refer to it as a trail. Your spell checker won’t catch these mistakes, either. (You can find more tips about legal writing in