Chapter 10

The Paper Chase: Preparing Documents

IN THIS CHAPTER

Getting familiar with the voluminous amount of civil case documents

Getting familiar with the voluminous amount of civil case documents

Grasping the techniques for creating powerful and proper legal documents

Grasping the techniques for creating powerful and proper legal documents

As a paralegal, you need to familiarize yourself with all the types of documents that are relevant to the practice of law. This chapter covers the most important civil law legal documents in rough chronological order as they show up in the course of litigation. We focus on civil law rather than criminal law because paralegals are most apt to prepare documents for civil litigation. These documents range from the demand letter that tells the opponent to “cough up” prior to filing a lawsuit all the way to the appellate brief that seeks to either overturn a losing decision or uphold a winning verdict. After we explain what each document is used for and what it contains, we show you what they look like and give you tips on how to draft each one.

Communicating in Writing: Types of Legal Documents

We think that the best way to introduce you to the multitude of legal documents involved in a common civil law action is by taking you through a hypothetical case. In order to highlight the important types of legal documents, assume that a prospective client, Kelley Klutz, has just slipped and fallen on the vinyl tile surface of Worst Deal electronics store while comparing the prices and features of karaoke machines. As a result of the fall, Mr. Klutz suffers a broken hip. Mr. Klutz knows of a particular law office’s reputation for integrity, competency, and great paralegals, so he calls and briefly discusses his case with the attorney, Ima Gogetter.

Getting started: Preliminary documents

Ms. Gogetter suggests that Mr. Klutz arrange an appointment with her paralegal and asks the paralegal to prepare an intake memorandum based on the initial client interview. The intake memo summarizes background information about Mr. Klutz, details the facts of the slip and fall, and proposes the action that Mr. Klutz would like the law office to take on his behalf. An intake memorandum is just one of the many types of memoranda of law that paralegals often prepare. After submitting this intake memo to Ms. Gogetter, Pat Paralegal calls Mr. Klutz to tell him that Ms. Gogetter has offered to represent him in a slip-and-fall action against the electronics store under a contingent fee agreement.

A contingent fee agreement is one where the attorney gets paid only if the client wins the lawsuit. In other words, the attorney’s fees are contingent on a favorable outcome of the case. A retainer agreement, on the other hand, provides that the client pays the attorney an hourly fee for services no matter what the outcome. In either case, although the attorney might make advance payments for necessary costs associated with litigation, the client is ultimately responsible for repaying those costs regardless of whether the case is won or lost.

After reading and agreeing to the terms of representation, Mr. Klutz and Ms. Gogetter execute the contingent fee agreement and the attorney/client relationship begins. A typical contingent fee agreement stipulates that if the case is settled before trial, the client will keep 67 percent of the settlement proceeds after costs are deducted, and the attorney will keep the remaining 33 percent. If the case doesn’t settle before trial, a typical contingent fee agreement provides that the attorney will retain 40 percent, or even 50 percent, of the award as a result of a favorable trial court decision. The contingency percentages are negotiable so that given a strong case with clear-cut liability, the attorney may agree to keep less than 33 percent because strong cases don’t usually require lengthy settlement negotiations or trials.

Defendants in tort cases (cases that concern non-contractually-based civil wrongs) and both parties in non-tort cases (civil cases that don’t involve a tort, such as contracts and divorces), usually execute retainer agreements with their attorneys. Retainer agreements provide for a certain sum of money to be paid up front as a retainer and specify an hourly fee for services, which are usually billed monthly. The monthly bill will draw down the retainer fee until it’s depleted, and the lawyer might request the client to pay an additional retainer amount as security for continued billings.

After the attorney/client relationship has been established, Ms. Gogetter attempts to resolve the dispute without litigation. In fact, even though the number of lawsuits increases every year, civil litigation should be the last resort for the resolution of disputes. Attorneys, with the help of their paralegals, should explore all efforts at settling cases without litigation, including mediation and arbitration.

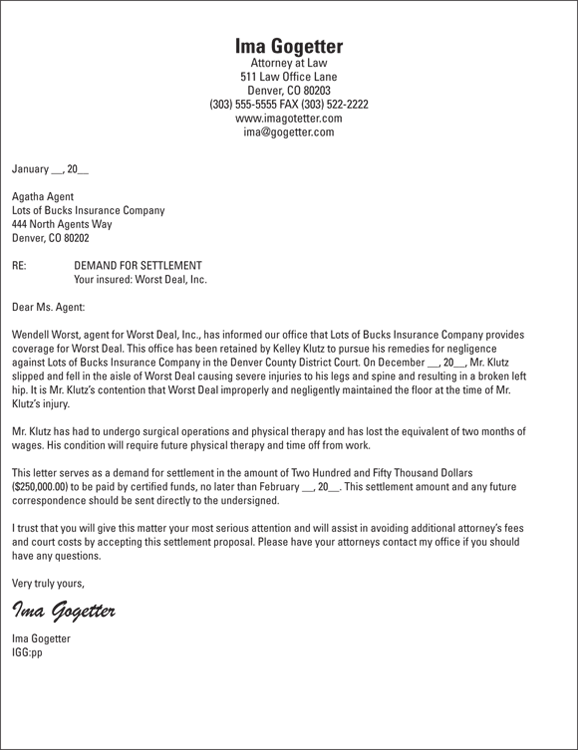

The initial effort to resolve litigation involves making Worst Deal aware of the damages Mr. Klutz has sustained as a result of Worst Deal’s negligence, so the paralegal prepares a demand letter. This demand letter notifies Worst Deal of the circumstances underlying the damages that Mr. Klutz has sustained and provides Worst Deal the opportunity to settle the dispute for a specific amount of money to avoid litigation. Demand letters usually allow the defendant 30 days to respond before the plaintiff initiates litigation. After Ms. Gogetter proofs and signs the letter, Pat Paralegal sends it to Worst Deal or its insurance company. (See “Commanding attention: Format of a demand letter,” later in this chapter, for an example of a demand letter.)

Begging for attention: Pleadings

Not surprisingly, demand letters seldom end disputes. What self-respecting defendant wants to part with cold hard cash without making the plaintiff work for it, right? As soon as the response time period provided in the demand letter expires and it appears to Ms. Gogetter that the matter will not be resolved without litigation, the paralegal drafts a complaint to be served on Worst Deal and filed with the court. The defendant, Worst Deal, then responds with an answer to this complaint. It’s up to Chris (the paralegal for Worst Deal) to make sure that the attorney responds to the complaint within the specified deadline. In fact, Pat and Chris are responsible for maintaining a tickler system throughout the litigation process to make sure no deadlines get missed. (For more about tickler systems, see Chapter 17.)

A PLEA FOR HELP: COMPLAINTS

The complaint presents the prima facie case against Worst Deal and requests damages or other relief. (You can see what a complaint looks like in the “Making your case: The complaint” section, later in this chapter.) The complaint should be served with a summons, which is a document issued by the court explaining that Worst Deal has been sued and that it has a certain time limit in which to respond to Mr. Klutz’s allegations. Pat Paralegal merely fills in the blanks in the summons with the necessary information.

In Mr. Klutz’s case, Pat Paralegal prepares a complaint that says the electronics store was negligent and requests damages to compensate for Mr. Klutz’s medical bills, lost wages, and pain and suffering. Pat also prepares the summons and submits it with the complaint to Ms. Gogetter for her review and signature. With Ms. Gogetter’s approval, Pat arranges that both the summons and complaint be served upon the electronics store or its designated agent.

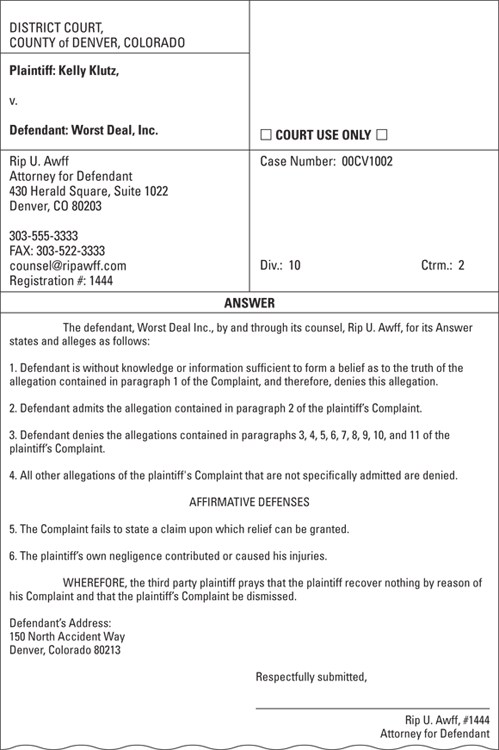

A LITTLE GIVE AND TAKE: ANSWERS AND REPLIES

Within about 20 to 30 days of service of process, depending on your state’s rules of civil procedure, Worst Deal prepares an answer to the complaint. The answer either admits or denies each of Mr. Klutz’s allegations. The answer may also include affirmative defenses. For instance, Worst Deal might allege that Mr. Klutz was contributorily negligent because he was running at the time of the slip and fall. (You can find out more about affirmative defenses in Chapter 5.)

Worst Deal may also assert a counterclaim against Mr. Klutz for damages that the electronics store sustained because Mr. Klutz knocked over four of the store’s karaoke machines as he was falling. Talk about adding insult to injury! If there are multiple defendants, Worst Deal may file a cross claim. For instance, Mr. Klutz may sue the independent cleaning company that maintains the floors at Worst Deal or the manufacturer of the floor tiles.

In many states, after the defendant files the answer to the complaint, the plaintiff may then file a reply to the answer. A reply responds to the new matters or allegations that may have been brought up in defendant’s answer. (You’ll find a sample answer in “Striking back: The answer,” later in this chapter.)

BLAMING OTHERS: THIRD-PARTY COMPLAINTS

Another pleading that may be served and filed is the third-party complaint. Through a third-party complaint, the defendant may bring a new party, or parties, into the litigation who wasn’t listed in the original complaint and who may be liable to the plaintiff for some or all of the damages alleged by plaintiff. So, Worst Deal could file a third-party complaint against the manufacturer of the vinyl floor tile alleging that this tile should have prevented slips and falls and was, therefore, defectively designed and manufactured. The tile manufacturer would become a third-party defendant and would have to file an answer to the third-party complaint filed by the electronics store.

Making your move: Motions

A motion is a legal document that requests the court to take specific action or else order that one or more of the parties takes some action. Think of a court as having a whole lot of inertia, and in order to get it to do anything, you have to move it. When you bring a motion, you are “moving the court” to take action. Although the defendant may file a motion to dismiss in response to a complaint, most motions occur during and after discovery. (You can read more on discovery in “Playing detective: Discovery,” later in this chapter.)

All sorts of pretrial motions exist:

- Motion to quash: If a party receives improper service of process, that party may file a motion to quash service of summons or a motion to quash the return of the service of summons.

- Motion for change of venue: A defendant could file a motion for change of venue if he feels that a fair trial can’t be had in the court or county where the suit was filed.

- Motion to recuse: Either side could file a motion to recuse if it feels the appointed judge is biased and should be disqualified from presiding over the case.

- Motion for more definite statement: A defendant can file a motion for more definite statement in response to a complaint that lacks enough clarity or specific detail for the defendant to answer the allegations in the complaint.

- Motion to strike: If a party doesn’t like the language in the pleading, it can file a motion to strike. This doesn’t mean that the party is asking the court to hit the opponent (even though the thought may appeal to him). The motion to strike asks the court to delete part or all of the allegations in a pleading, especially if those allegations are scandalous or indecent.

- Motion to file an amended pleading: If a party wants to add some information or name an additional party defendant or just fix a mistake in the initial pleading, she can file a motion to file an amended pleading to add or subtract a party to the litigation or otherwise change some aspect of a pleading on file.

- Motion for enlargement of time: This motion is a commonly filed request that the court grant additional time for one of the parties to take some action or file a notice, motion, or brief.

- Motion for protective order: The party who feels a discovery document contains irrelevant questions or feels like the other side is abusing the discovery process may file a motion for a protective order, in which she asks the court to rule on whether she has to respond to all or some of the discovery.

- Motion to compel: Conversely, if a party doesn’t respond on time to a discovery or provides incomplete or evasive answers, the opposing party may file a motion to compel the answers to the discovery.

- Motion in limine: Another pretrial motion is a motion in limine in which either party requests that the court limit what the jury hears about a specified piece of evidence, usually because that evidence is irrelevant or too gruesome or in some way unduly prejudicial.

- Motion for judgment on the pleadings: Either party can make this motion, which merely asks the court to review all the pleadings (that is, the complaint, answer, and reply) and make a decision on those documents alone.

- Motion for summary judgment: Similar to a motion for judgment on the pleadings, this motion claims that the parties don’t dispute the material facts in the case and, therefore, requests that the court reach a decision on all or a portion of the case on the basis of the pleadings and any affidavits of facts without conducting an entire trial. If the court grants the summary judgment motion, it saves the moving party lots of time and money in litigation costs. (You can see an example of a motion for summary judgment in “Exerting your will: Motions,” later in this chapter.)

More motions can appear during the trial and post-trial phases of the proceedings:

- Motion for directed verdict: During trial, either party may file a motion for directed verdict requesting the court to enter a verdict in favor of the party making the motion. The defendant may request a directed verdict after the plaintiff has rested her case, and the plaintiff may request a directed verdict after the defendant has completed his defense.

- Motion for a new trial: After the court or jury has rendered a decision, either side may request a motion for new trial asking the judge to set aside the verdict or judgment and grant a new trial to the parties.

- Motion to amend judgment: Similarly, a motion to alter or amend judgment requests that the judge change, modify, or otherwise vary the judgment rendered.

- Motion for a judgment notwithstanding the verdict: Another way a party can get post-trial relief from the trial judge is to ask for a motion for a judgment notwithstanding the verdict, otherwise known as a JNOV (an acronym for the phrase “judgment non obstante veredicto,” or judgment notwithstanding the verdict). This motion asks the court to set aside the jury’s verdict that was, as a matter of law, allegedly rendered incorrectly.

The great paper waste: Discovery

Generally, after the last pleading is filed, the discovery stage of litigation commences. During discovery, each party seeks information from the other in an effort to learn as much about the other party’s position as possible, prevent surprises at trial, and settle the case prior to trial. Discovery can be either written or oral.

THE WRITTEN RECORD

Each side can serve the following discovery documents upon the other side:

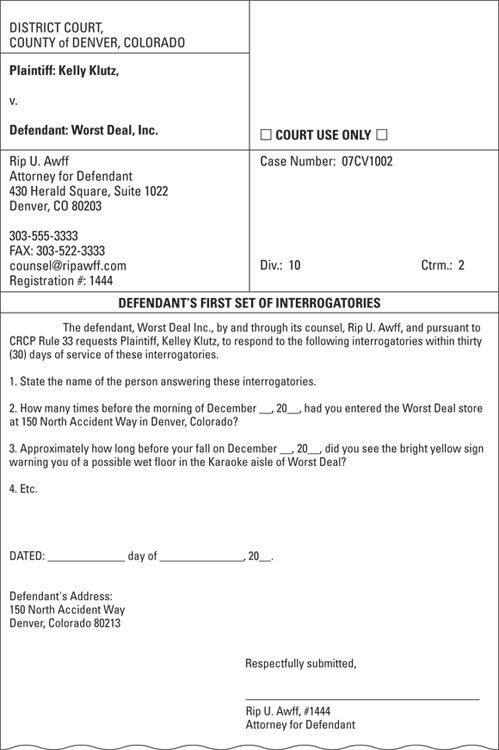

- Interrogatories are written questions that require a response with written answers that are provided under oath. (You can see an example of written interrogatories in “Playing detective: Discovery,” later in this chapter.)

-

A request for admissions asks a party to admit to the truthfulness of facts or opinions or verify the genuineness of documents. (You can find a sample request for admissions online.)

A request for admissions asks a party to admit to the truthfulness of facts or opinions or verify the genuineness of documents. (You can find a sample request for admissions online.) - A request for production of documents asks that one party be allowed to inspect or duplicate documents or other materials that are relevant to the subject matter of the litigation. Parties may also request permission to enter land for the purpose of inspecting it.

- A request for a physical or mental examination asks a party to submit to a physical or mental examination to determine the legitimacy and extent of the physical or mental injuries claimed by that party. Examinations usually require a court order.

THE SPOKEN WORD

A deposition is another common form of discovery where a witness or party provides oral testimony under oath in a location outside of a courtroom, often the conference room of the opposing attorney. A deposition requires the presence of a court reporter to swear in the witness and to create a verbatim (word-for-word) transcript of witness testimony. Parties usually undertake other written forms of discovery before launching into a deposition because holding a deposition is expensive. The key is to find out information ahead of time so the deposition yields more useful information. Depositions generally allow the parties to find out a whole lot more information than the interrogatories or requests for admission or production. At the very least, depositions draw on the knowledge gained from the other written forms of discovery before the parties spend the big bucks on the deposition.

In the electronics store slip-and-fall scenario, both parties submit interrogatories and requests for admissions to each other in an effort to determine background information, insurance coverage, and facts underlying the incident. A request for production of documents would also be appropriate to gather documentation regarding the earnings of both parties, possible existing insurance policies, and other information relevant to the action. Finally, Worst Deal could serve a request for physical examination upon Mr. Klutz, requiring him to be examined by the electronics store’s physician to assess the severity of his broken hip.

Taking it to the judge: Trial and post-trial documents

As the trial nears, paralegals really earn their keep when they help prepare and file pre-trial statements. A pre-trial statement is a lengthy document outlining the manner in which each party plans to proceed up to and during trial. The contents of the pre-trial statement are products of the pre-trial conference. When it becomes likely that the case will go to trial, the paralegal assists in the preparation of the trial brief, a document that states the legal issues of the case and establishes the validity of the party’s position on each issue.

After the trial, paralegals assist in the preparation of documents that assist in the collection of judgment, such as writs of execution, garnishment, and attachment. If a party loses the case, the paralegal may prepare and file a notice of appeal, a designation of record on appeal, and an appellate brief (which presents the reasons that the party thinks the trial court erred). The party that was victorious in the trial court responds to the appellate brief with an answer brief, to which the other party may respond with a reply brief.

Making the Case: Effective Document Drafting

In the previous sections, we let you in on the significance of common legal documents. Here, we give you the ins and outs of how to draft them.

This section shows you some techniques you can use to draft specific documents. The sample documents in this chapter follow Colorado rules, which, like those of most states, are similar to the federal rules.

Commanding attention: Format of a demand letter

You’ll find a wealth of rules, and even whole books, that have been written about proper ways to format a letter. Some paralegals prefer to follow a strict structure to be satisfied that they’re doing the work right, and plenty of material is available in bookstores and libraries to fill this need. For most paralegals, however, following some simple rules, using good judgment, and having pride in appearance will suffice. And spell-check isn’t bad either!

- The facts surrounding the incident for which the plaintiff is demanding settlement

- A settlement proposal of either a specific dollar amount or specific action

- The time period in which the defendant must respond

- Vary the letter’s margin widths depending on its size.

- Short letters: Give very short letters wide left and right margins (usually 1.75″) with a few extra lines placed before and after the date line. Place the body of the letter (address through signature line) at the page’s optical center, which is slightly above the exact center of the page.

- Medium-length letters: Give medium-length, one-page letters margins of 1.25″ to 1.5″ and a little less space before the date line.

- Long letters: Give longer one-page letters 1″ margins left and right. Place the date line two lines below the letterhead, and begin the address line two lines below the date line.

- Avoid making an orphan of the signature block on the second page of a letter. Often, you can fit the body of a letter nicely on one page, but the signature block sometimes spills over onto a second page. To avoid the orphan signature block, you can make the margins wider and force some of the text (preferably a full paragraph) to the second page.

- Always put a colon after the salutation line, even if you use only a first name, like this:

- Dear Ms. Gogetter:

- Dear Ima:

- Don’t number the first page but number the second and succeeding pages of any letter. The style and placement of page numbers doesn’t matter, but your office probably has its own procedure, so be sure to ask how they want it done.

- Begin the complimentary close with a capital letter and end with a comma, like this:

- Very truly yours,

- Yours truly,

- Place about five lines between the complimentary close and the name of the attorney. This gives plenty of room for the signature.

-

Reveal the identity of the letter writer by presenting his initials in the block following the signature block. Capitalize the writer’s initials and leave the word processor’s initials in lowercase. For example, if Pat Paralegal were creating a letter for Ima Gogetter, Pat would type “IG:pp” after the signature block.

Follow the initials with a statement of whether there are enclosures and whether copies have been sent to others. Place these revelations underneath the initials and flush with the left margin. Here’s an example of the ending of a letter that contains enclosures with copy information (the cc used to stand for carbon copies back in the olden days before computers and copy machines; now it can stand for courtesy copies):

- IGG:pp

- Enclosure

- cc: Rip U. Awff, Esquire

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 10-1: A sample demand letter.

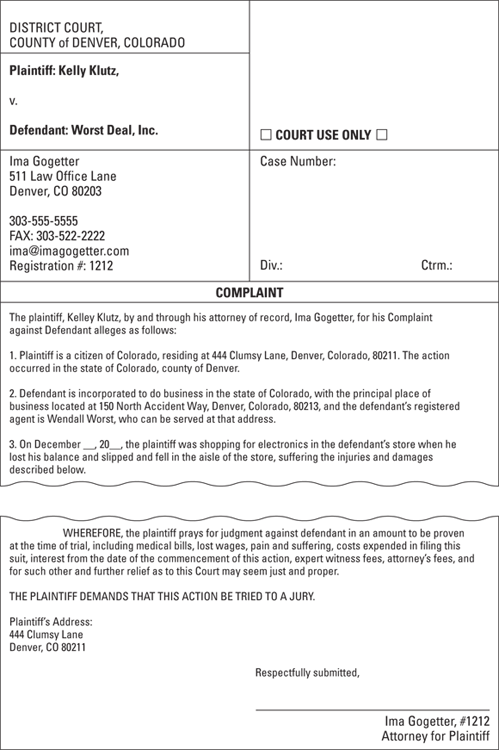

Making your case: The complaint

The format of a complaint (which, in some states and in certain types of lawsuits, is called a petition), varies from state to state, but all complaints should include a caption, text, and a subscription (the attorney’s signature).

Because you personally serve a complaint on the defendant, it doesn’t include a certificate of mailing (a statement certifying that you placed the document on a particular date to a specific address). You also file a certificate of personal service with the court.

We cover all of these items in the following sections.

Identifying the action: The caption

The caption states the court in which the action is filed, the case number, the name of the document, and the names of the parties to the action. A line on the document usually separates the caption from the text of the complaint. Each state has a specific format you should follow for the captions of legal documents.

Telling the story: Text

The text of a complaint must include the following elements in the form of numbered paragraphs in the order that they’re listed here:

- An opening paragraph

- A statement of jurisdiction and venue

- A statement of the general allegations against the defendant, which include the specific elements of the offense and the resulting damages

- A prayer for relief

IN THE BEGINNING: THE OPENING STATEMENT

The opening statement introduces the complaint and explains its purpose. The legal community is slowly changing its format to include clearer, more precise language that omits unnecessary legalese. Old expressions such as whereas and wherefore don’t appear as often as they used to. Even the time honored introductory phrase, “Comes now the Plaintiff, by and through his attorney …” is giving way to more straightforward wording, “The Defendant, by his attorney… .”

A LITTLE CONFIRMATION: ESTABLISHING PARTIES AND JURISDICTION

The first numbered paragraph of the text usually identifies the parties with names and addresses and states facts to support the alleged jurisdiction of and venue for the action. For example if the plaintiff brings the lawsuit in a federal district court and relies on diversity of citizenship to give the court jurisdiction, the opening paragraph of the complaint will allege the plaintiff is a citizen of one state, that the defendant is a citizen of another state, and that the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000.

THE HEART OF THE MATTER: STATING THE CASE

The body of the complaint asserts in numbered paragraphs statements that present the case in a logical and sequential order. There’s a difference of opinion on how much detail is needed in alleging the facts on which the plaintiff bases her recovery. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP) and most state rules have come a long way from the old days and require very little factual detail. The discovery process usually fleshes out many of the specific facts in the lawsuit. In a negligence action, alleging that on a certain date, at a described place, the plaintiff slipped and fell on the floor of the defendant’s business, which resulted in crushing the plaintiff’s hip, required him to seek medical help and miss work, and which also resulted in incurred expenses of a specified amount is usually sufficient.

MONEY MATTERS: THE PRAYER FOR RELIEF

The complaint concludes with a prayer for relief or ad damnum clause, which is a short summary of the plaintiff’s request. This statement may be as simple as, “Wherefore, the plaintiff demands judgment against the defendant in the sum of Two Hundred Fifty Thousand Dollars ($250,000.00) with interest, attorney’s fees, and costs.” Or it may consist of several pages of demands. The prayer for relief may also be more generally worded like this, “The plaintiff demands judgment against the defendant in an amount to be determined at the time of trial, including interest, attorney’s fees, and costs.”

The big finish: The subscription

The subscription is the attorney’s signature block. It must contain the attorney’s name, registration number, mailing address, and phone number. Many states also require that the plaintiff’s name and address appear opposite the subscription.

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 10-2: A sample complaint with the Colorado caption format. Remember to check the correct caption format in your state.

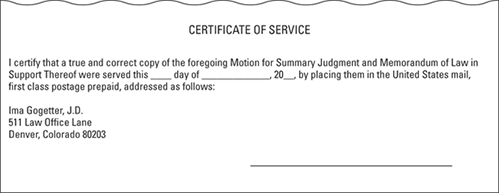

Striking back: The answer

When Worst Deal receives service of Mr. Klutz’s complaint, Worst Deal’s attorneys respond with an answer. State law or court rules generally govern the time period a defendant has to respond, which is also spelled out in the summons. Within the specified time limit, as a paralegal for the defendant’s attorney, you may draft the defendant’s answer to the plaintiff’s complaint. You then present it to your supervising attorney for approval and signature and file it with the court. The components of an answer pretty much mirror those of a complaint: The answer begins with the same caption as the complaint and ends with a subscription. The text of the answer usually begins with an introductory statement followed by the defendant’s allegations.

Within the allegations, the defendant either admits or denies the allegations the complaint has raised. In forming responses for your attorney’s client, make sure you provide a specific admission or denial for every allegation. To cover your bases, include an allegation such as the following: “All other allegations of the plaintiff’s complaint that are not specifically admitted are denied.”

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 10-3: A sample answer with the Colorado caption format.

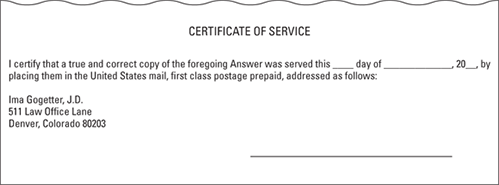

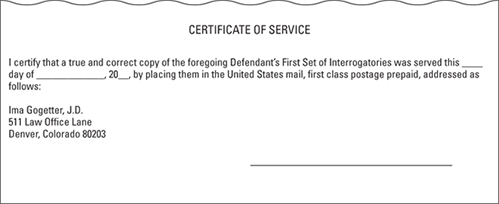

After the subscription, include a certificate of mailing or certificate of service to be signed by whoever mails the answer to the other parties or to the attorneys representing the other parties. This certificate functions as a verification of service of the document by mail or hand delivery. Any document that isn’t personally served on another party must contain a certificate of service.

The defendant may also include within the answer a third-party complaint. The allegations of this complaint come after the answer’s affirmative defenses and bring another party into the action.

Presenting a formal analysis: The memorandum of law

The legal memorandum is among the most commonly used documents of the paralegal profession. Through legal memoranda, paralegals convey information to clients and witnesses, analyze complex legal problems, and present the client’s case to others.

Legal memoranda may be internal or external. You send an internal memo to your supervising attorney or other member of the law office staff but send an external memo outside of the law office to the opposing counsel, the court, or both. The major difference between an internal memo and an external memo lies in how you present the case. Internal memos anticipate all legal issues by portraying both sides of a client’s case, favorable and unfavorable. External memos, such as trial briefs or memoranda in support of motions, convey only the favorable points of a client’s case.

The components of a legal memorandum

The parts of a legal memorandum include a caption, a statement of the assignment, a statement of facts, a list of issues, an analysis of the issues, a conclusion, and, in many cases, recommendations.

THE CAPTION OR HEADING

The caption (like the one in Figure 10-4) includes information indicating who the memo is addressed to, the name of the writer, the date the memo was written, the case name and number if available, and a brief explanation of what the memo is about.

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 10-4: The caption of a memo of law, including a statement of the assignment.

THE ASSIGNMENT

This one-sentence statement describes the purpose of the memo. It’s sometimes included in the caption (refer to Figure 10-4).

THE FACTS

This section briefly outlines the facts of the case that you’ll use in the legal analysis. For an example, see Figure 10-5.

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 10-5: A statement of facts.

THE ISSUES

The issues section lists the important questions of law and presents the issues as questions to be answered in the analysis. (See Figure 10-6 for an example.) The attorney often provides the issues, but as a paralegal, you may have to formulate issues on your own to submit to your supervising attorney for revision or approval.

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 10-6: A statement of the issues.

THE ANALYSIS

Analysis is the process of answering each issue through a careful and thorough application of the law to the facts of the client’s case. Figure 10-7 provides a portion of a sample analysis.

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 10-7: A portion of a legal analysis of an issue.

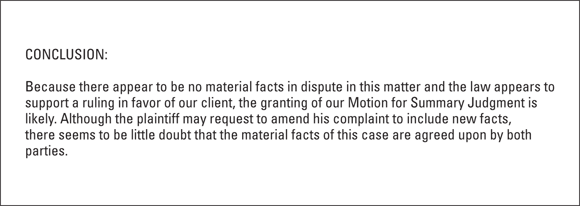

THE CONCLUSION

The conclusion summarizes the answers to the questions posed by the issues. The conclusion, like the one shown in Figure 10-8, should be based on the legal analysis and shouldn’t contain any information that hasn’t been discussed in the analysis section.

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 10-8: A conclusion to a memo of law.

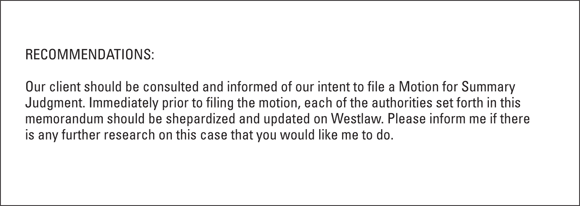

THE RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the conclusion, this section proposes what steps should be taken on behalf of the client (see Figure 10-9). You generally only find this section in internal memoranda.

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 10-9: A recommendations section of a memo of a law.

The process of legal analysis

The focal point of the memorandum of law is the analysis. Legal analysis is the means of providing an answer to an issue through careful application of the points of law of applicable statutes and previous cases to the specific facts surrounding the client’s case. If you get good at analyzing the law, you’ll be invaluable to your employer.

Through legal analysis, you apply a relatively unchanging body of law to the specific facts of your client’s case (refer to Figure 10-7). You apply law to facts because law changes far less frequently than facts do.

-

Introduce the analysis by restating the issue to be analyzed and then listing the elements of the pertinent legal authority.

Analysis of a previous case requires a very brief, two- to three-sentence explanation of its relevant facts and issue. Analysis of a statute requires isolating its most important elements.

- Isolate the court’s decision in the precedent case.

-

Carefully apply the precedent authority to the facts of the client’s case.

By comparing and contrasting the facts and issues of the precedent case with the facts and issues of the client’s case, you determine whether the precedent case’s decision applies to the client’s case. By analyzing the important elements of a statute, you show how the client’s case applies to the legislative intent of the statute.

-

Based on the application of the legal authority to the facts and issues of the client’s case, present a conclusion that answers the issue.

You may derive the conclusion from an analysis of several different cases and statutes or from an analysis of just one case or statute.

If the supervising attorney provides specific cases and statutes to analyze, discuss all the authority provided. Internal memos of law may include an analysis of legal authority that’s detrimental to the client’s case to help the attorney anticipate the opposing party’s case.

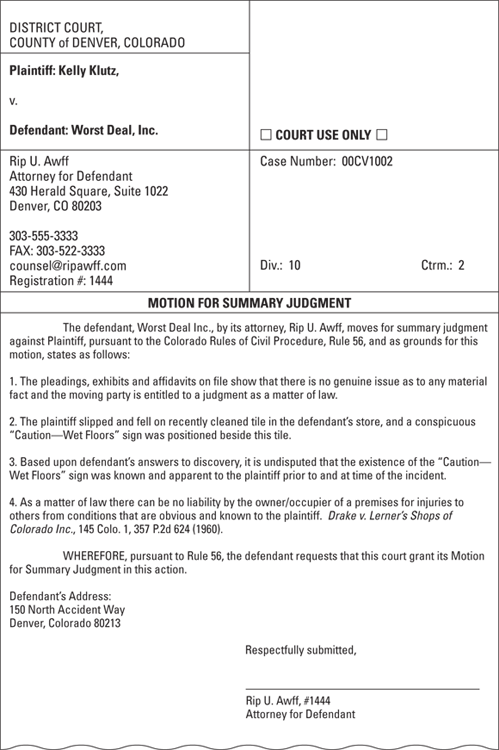

Exerting your will: Motions

The format of a motion strongly resembles that of a pleading. Just like all other documents filed with the court, the motion begins with a caption. The text of the motion consists of an introductory statement, a list of reasons why the court should grant the motion, and a request that the court grant the motion. Like answers, motions must contain certificates of service. Figure 10-10 contains an example of a motion for summary judgment.

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 10-10: A sample motion for summary judgment.

When you draft a motion, you also prepare a notice to set hearing on the motion, a memorandum of law or brief in support of the motion, and a proposed order to accompany the motion. All these documents are headed with the caption of the case, ended with a subscription, and completed with a certificate of service. Here’s more about the purpose of these documents:

- Notice to set hearing: You send the notice to set hearing to the opposing parties to notify them of the time and place for the setting of the hearing on a motion.

- Notice of hearing on motion: When the hearing has been set and if your attorney’s client is the movant (the moving party), you prepare a notice of hearing on motion, which has a similar format to the notice to set hearing on motion.

- Memorandum of law in support of the motion: You draft a memorandum of law in support of the motion to present the points of law in support of the motion. In it, you state the purpose of the motion, the burden of proof, and the reasons that the movant is entitled to have the motion granted. You substantiate each of these points with an analysis of the applicable law as it relates to the facts of the case.

- Order: For those courts that require an order, the movant submits a prepared order in hopes that the court will rule in favor of the movant’s motion. The text of the order states that the motion has been granted and provides a signature line for the court.

Playing detective: Disclosure and discovery

As a paralegal, you may get involved in the disclosure and discovery process by preparing proper disclosures in accordance with the rules of civil procedure. You may also be assigned to choose appropriate questions for interrogatories, coming up with admission statements for the request for admissions and making lists of necessary documents for the request for production of documents. You can also assist your supervising attorney in digesting the deposition document.

Preparing written discovery

Written discovery documents begin with the caption of the case. The text includes an introductory statement that provides the time limit that the other party has to respond to the discovery request. Depending on the type of discovery document, the text then continues with a list of interrogatories, statements to be admitted, or items to be produced that are relevant to the issues of the case. Usually, these lists are quite lengthy, requiring the other party to spend a great amount of time and effort to fulfill the conditions of the discovery. So, many state courts put limits on the number of interrogatories and sets of interrogatories a party can submit. These documents end with a subscription (the attorney’s signature) and a certificate of service.

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 10-11: Sample interrogatories.

Digesting depositions

Depositions usually take place after the parties have responded to written discovery. The deponent (the person being deposed) may be a party or a witness to the action. As a paralegal, you may serve the deponent with a subpoena and a notice of deposition (similar in form to a notice to set) and send the notice of deposition to all the parties in the action. Through the use of a subpoena duces tecum, the deponent may be required to bring specific items (like company records, medical records, and so on) with him to the deposition. Depositions usually take place in the attorney’s conference room where a certified or registered shorthand reporter swears in the deponent. Any objections to questions made by counsel during the deposition are preserved for a judge’s review, and the oral testimony is transcribed for use in the court trial.

The attorney may ask you, as the paralegal, to digest the transcribed deposition. No, you don’t eat the transcript! To digest a deposition, you use a memorandum of law to summarize the deposition for your supervising attorney. Your supervising attorney dictates the form of the digest. For instance, the attorney may want a 500-page deposition to be synthesized into a 5-page summary, or the attorney may want you to summarize only certain issues discussed in the deposition. If the deposition has been video recorded, you may assist in determining which portions would be best to show at trial.

Handling trial documents

If a case goes to trial, you usually prepare a trial notebook for your supervising attorney. The trial notebook contains the information your attorney needs to successfully conduct the client’s case during trial. The contents of the trial notebook vary but usually include copies of pleadings and motions, witness lists, deposition digests, a copy of the trial brief, which outlines the arguments of the client’s case, and jury instructions. As a paralegal, you may be especially helpful in putting together the documents concerning the jury.

Jury instructions

When both parties have rested their cases, the judge gives the jury a series of instructions that explain the legal principles it should use when it deliberates. Often, attorneys make suggestions to the judge regarding what instructions they’d like the jury to hear. The paralegal often gets tagged with preparing the suggested jury instructions, and many law offices have sets of instructions for each type of case they try. So, from these sets you choose the instructions that apply to the case on trial and present them in written form, numbered and double-spaced.

Special verdict form

Sometimes, a jury will be asked to complete a special verdict form. This form contains questions that the jury must answer in rendering its verdict. The form begins with the case caption, presents several questions, and ends with the signatures of all the jury members or the presiding juror (the foreperson). Again, as the paralegal, you may have a hand in preparing this form for your supervising attorney.

If the law firm decides not to represent the client, communicating that fact in writing to the potential client as soon as possible is extremely important. Although the attorney decides whether to take on a case, the paralegal is often responsible for making sure the law firm notifies potential clients about the attorney’s decision. So, you need to keep track of the status of cases after the initial client interview and gently remind your supervising attorney if he hasn’t made a decision about a client within a reasonable period of time.

If the law firm decides not to represent the client, communicating that fact in writing to the potential client as soon as possible is extremely important. Although the attorney decides whether to take on a case, the paralegal is often responsible for making sure the law firm notifies potential clients about the attorney’s decision. So, you need to keep track of the status of cases after the initial client interview and gently remind your supervising attorney if he hasn’t made a decision about a client within a reasonable period of time. The summons and complaint together are known as process. The complaint shows a prima facie case against the defendant, meaning the document on its face contains enough allegations that, if believed, would cause the court to order the defendant to pay damages or some other form of relief to the plaintiff.

The summons and complaint together are known as process. The complaint shows a prima facie case against the defendant, meaning the document on its face contains enough allegations that, if believed, would cause the court to order the defendant to pay damages or some other form of relief to the plaintiff.