Chapter 18

Law Office Management 101

IN THIS CHAPTER

Making the most of your time

Making the most of your time

Acting as rainmaker with orderly billing procedures

Acting as rainmaker with orderly billing procedures

Finding a place for everything and putting everything in its place

Finding a place for everything and putting everything in its place

How much time you spend engaged in law office management depends on the type and size of firm you work for. Most large firms employ a separate staff to take care of the majority of the daily organization activities. But no matter what size firm you work for, as a paralegal you’ll probably end up doing some managing and organizing of the law office. If you work for a small firm, you could be responsible for the management of the entire office. In a larger firm, you’ll probably be responsible for just your own schedule and maybe that of your supervising attorney. Although it may seem pretty mundane, proper office management is crucial to the productivity of any law environment, so this chapter focuses on proper management of time, files, and monthly billings.

Buying Time: Management Systems

When you think about it, law firms sell their time to their clients, so the value of managing minutes, hours, and days is absolutely crucial. The legal process consists of a series of deadlines that you must meet if you don’t want to jeopardize a client’s case. Good time management produces efficiency and profit, but poor time management can terminate legal careers. If you have trouble organizing your time, now’s a great time to learn and practice time management skills.

Marking the days: The calendar system

Keeping track of time begins with a good calendar system. If you’ve never used a daily planner before, you’d better get used to using one. Calendars are absolutely essential to the smooth running of any law office.

The master calendar

Every law office must maintain a master calendar that the attorney, legal secretary, paralegal, and other staff can easily access. It’s usually available on the computer network for everyone to see. The main calendar keeps track of all the important events for the entire office, including the following:

- Court appearances

- Important filing deadlines

- Appointments

- Meetings and conferences

- Vacations and personal days of all staff members

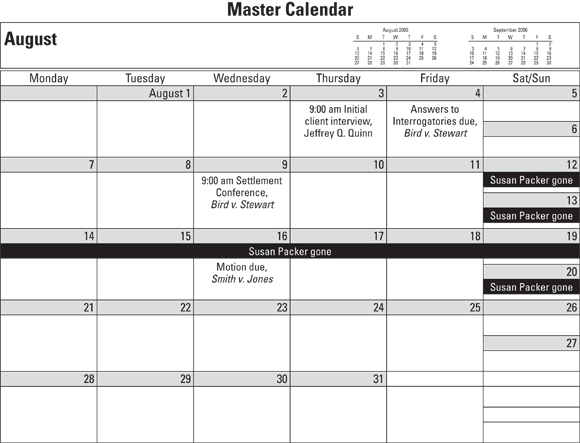

Figure 18-1 shows a sampling of two weeks of a master calendar.

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 18-1: A master calendar such as this one is where you record all the key events for the entire office.

Individual calendars

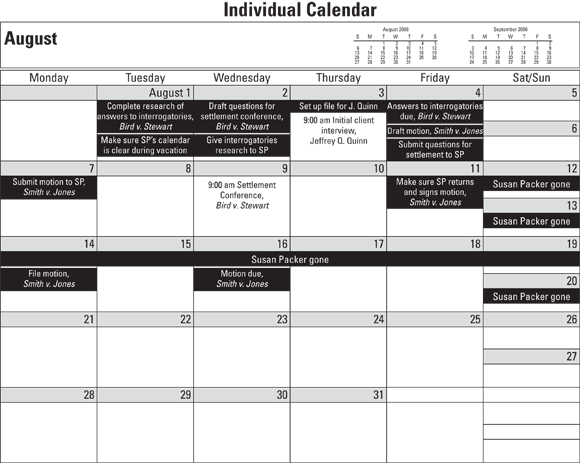

The master calendar (see the preceding section) isn’t the only time keeping device in the office, though. You’ll also use a series of individual calendars, like your own personal calendar or the attorney’s traveling calendar, that you regularly crosscheck against the master calendar. Individual calendars are also called redundant calendars because they contain copies of the entries from the master calendar that should be performed by that specific person. They also contain events and tasks that aren’t on the master calendar that only the owner of the individual calendar needs to know about (like a lunch meeting with a malpractice insurance agent).

In Figure 18-2 you can see what a paralegal’s calendar may look like based on the events on the sample master calendar in Figure 18-1.

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 18-2: An individual calendar helps you keep track of your own schedule or the attorney’s schedule.

Setting the alarm: The tickler system

If you’re using the calendar system (see the preceding section), you can set up a tickler system (a system that “tickles,” or jogs, your memory) that automatically alerts you when something must be done by a certain time. With the number of things going on in a law office and the number of times you’re interrupted in a day, even if you have an exceptional memory you won’t be able to keep track in your head of everything you have to do.

To make sure you complete a certain action by the day it’s due, you have to keep track of more than just the final deadline dates. So, you break each project into smaller pieces. Then you tickle those interim assignments, giving yourself enough time to accomplish what you need to do before you give it to the attorney to review, revise, or otherwise handle before the looming final deadline.

You can use any or all of the following methods to produce a reliable tickler system.

- Enter deadlines on the office’s master calendar with an appropriate lead time. So, if something is due on the 15th of the month, you also enter a reminder entry on the 10th.

- Use a document control register to track deadlines. In this system, you give a document control number to every document that leaves or comes into the office. Then you construct a register that lists the status of all documents by their control number, which you consult regularly for unfinished business and approaching deadlines.

- Note deadlines through the use of a tickler file (also known as a suspense file). If you want be absolutely sure you never miss a deadline, you can supplement your management system with a paper-based tickler file. You create 31 separate file folders for the days of the current month, 31 separate file folders for the days of the next month, and 12 file folders for the months of the year. Then you make a copy of the first page of every document that requires a response or action. These pages go into the file folder for a day that’s five or ten days before the action deadline. All you have to do is check the tickler file every morning and enter the required actions on your personal work schedule or to-do list.

The key, of course, for any of these methods is to check them daily and to have a personal tickler system to transfer information to. For example, if you know you’re responsible for gathering information to be used to answer interrogatories that are due at the end of the following week, you’d tickle this project much earlier on your own calendar than it appears on the master calendar. The tickler gives you ample time to gather the information and present it to your supervising attorney in time for the answers to be drafted, reviewed, signed, and sent.

Getting it in writing: The to-do list

From the tickler system (see the preceding section), you move to the daily to-do list, which, not surprisingly, is a list of all the things you need to accomplish that day, transferred from your tickler system. You’ll definitely create one for yourself every day, and you may have to make a daily to-do list for your attorney, too.

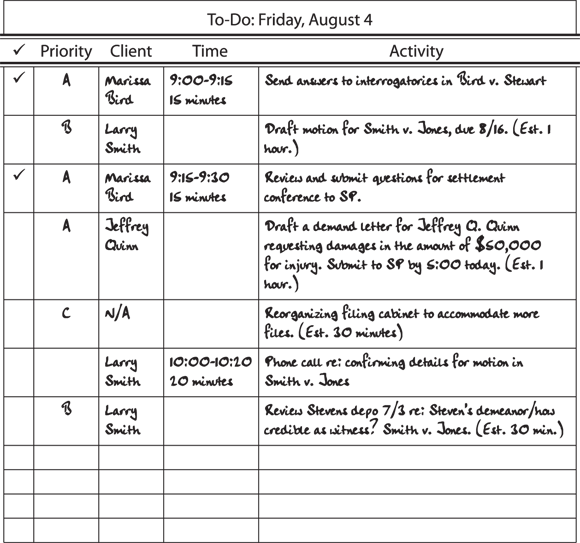

Each individual worker in a law office should have a separate to-do list. This list can be a handwritten list of things to do today, which requires a daily review of pending work and priorities, or it can be a similar list kept in the computer. Different members of the staff may use different types of lists. The best lists are ones that don’t list more than you can do in a day and that prioritize your activities so you know what you need to do first. You can easily prioritize your list by designating each activity with an A, B, or C. You do all the A activities first, then the Bs, and finally the Cs. Anything you don’t finish one day just goes on the next day’s list, probably with a higher priority than before.

Figure 18-3 shows what a to-do list would look like for Friday, August 4, based on the sample calendar (refer to Figures 18-2 and 18-3) with a few last-minute assignments added in.

© John Wiley & Sons

FIGURE 18-3: Your daily to-do list helps you prioritize your tasks and work toward your goals.

Of course, in addition to the events listed on the master and individual calendars, your supervising attorney will give you other daily assignments. When you get an assignment, write it on your calendar and/or to-do list right away, along with the exact instructions provided by the attorney. Estimate the time involved and enter any deadlines. Take a look at the fourth entry in Figure 18-3 for an example.

If you keep your to-do list with you throughout the day (in written form or on your phone), you have evidence of your assignment in sight at all times. You can easily get distracted and lose sight of what you’re doing, especially when you’re conducting research or even doing something simple like searching for a document in a file. You’ll save a lot of time if you only have to glance at your notes to remind you of your purpose.

Checking off completed activities on your list is one of the best feelings in the world! As you cross things off, keep a log of how much time you spent on each item and the name of the client so you’ll be prepared for billing when the time comes (see the next section). Then, at the end of each day, you just have to review your list to see what you’ve finished and what remains to be done. If you’re in the middle of an activity that you can’t finish, note where you are on your to-do list for the next day and put away the file — this clears the clutter from your desk and gives you a starting-off point for the next day.

Keeping Account: Billing Systems

A paralegal’s time may be billed to the client at an hourly rate lower than the attorney’s, so you’ll need to keep track of every minute you spend working on a client’s case. You then have to provide documentation of your time to the accounts receivable department of the firm so it can generate invoices. You need to keep track of your time even if your office handles a client on a contingency fee basis (where an attorney gets paid by receiving a portion of the client’s settlement). That way you have an accounting in the billing records if there’s ever a question of what duties you’ve performed for a client and when.

If you’re the accounts receivable department as well as the office paralegal, you need to generate invoices to clients on a set schedule. The invoicing process involves recording billable hours and fee, compiling those hours and fees by client, creating an invoice for each client, and keeping track of unpaid balances.

Recording time

Time is the element in an attorney’s inventory that has a direct dollar value, so a law practice should keep track of it just as a jewelry store keeps track of its diamonds. A number of commercial systems exist that keep track of time, some computerized and some manual. Some of the most popular accounting software programs, such as QuickBooks and Peachtree, contain stopwatches that you can set while you’re conducting a billable activity to keep track of your time. The program then computes the value of the activity based on your hourly billable rate, associates the time with a specific client, and keeps track of it until you’re ready to invoice the client. You don’t need special software, though. Most word processing programs have the invoice templates and merge features you need to set up a billing procedure.

Regardless of the medium you use, both you and the attorney keep track independently of the time you each spend on each task for each client throughout the month. Even if you use a software program that records time for you, keeping track of your time on your personal calendar or to-do list is a good idea. You can also keep track on your to-do list of how long you spend on the phone, as shown in the sixth entry in Figure 18-3.

On the designated monthly billing day, the accounts receivable department at your firm will either transfer your activities to invoices in the accounting software or you’ll submit a chronological list of the tasks you’ve performed for each client. If you’re responsible for the billing, you’ll compile the billable hours and fees for each client, prepare invoices, and usually submit them to the attorney for approval before you send them out.

Creating invoices

Recording time accurately is the first vital step in operating a profitable law office. The second vital step is to actually bill the clients for this time. The most efficient method for sending out bills on time is a simplified approach. Billing procedures vary widely depending upon the size and type of practice and the number of accounts receivable the firm has. Some firms may have a department dedicated solely to billing; others may use an independent firm to prepare their billings. Small firms usually rely upon the paralegal to perform this task.

The easiest way to manage accounts receivable in most law offices is through an accounting software program. The most popular programs, such as QuickBooks and Peachtree, allow you to compute time, record time, enter fees and other costs, and create invoices. You can enter time manually through a timesheet or you can have the software record time for you with its integrated stopwatch. You give the software a detailed description of the activity, associate it with a particular client, provide the hourly rate, and the software stores the information until you’re ready to invoice. You can also associate filing and recording fees and other billable costs to a client whenever you record the firm’s payment of those fees in the accounting software. Then, when you’re ready to send out periodic invoices, you just pull up the invoice form, enter the client’s name, and click a button. The software provides you with all the hours and fees associated with the client. You pick the ones you want to bill for and — abracadabra! — the invoice appears. It’s that simple. If you’re regular about entering time and fees into the accounting software, periodic billings can take only a few hours to complete!

A Place for Everything: File Management

One thing’s for sure: Law offices generate tons of paper documents. So, setting up and using a well-organized filing system is crucial to good law office management.

Maintaining a filing system

Odds are the law office you work for will already have an efficient filing system in place when you’re hired. Large firms likely store most documents digitally by scanning them and saving them on their servers, but they may still need to hang on to original paper documents, so a paper-based filing system is also necessary. The main purpose of a filing system is to make important papers instantly accessible. Generally, law firms keep files in alphabetical order by client, but some firms use a numeric system. Although assigning numbers to clients requires a cross-reference index (usually kept on computer), the number system is helpful because it provides a way of aging cases chronologically and makes filing completed cases much easier than an alphabetical arrangement. Color-coded labels or folders help to distinguish types of cases, and colored dots or other symbols identify whether a client’s case is in the pre-trial, trial, or post-trial stage.

Organizing documents in a file folder

In addition to a system for storing files, you also need a way to arrange papers within a file. The simplest procedure is to place the file’s documents in chronological order with the latest information on top. This system makes for easy setup, but as the file grows, its earlier contents become less accessible. Therefore, most offices that use the chronological method also keep a log in the file as an index, usually adhered to the inner left side of the folder. Maintaining the index requires extra time for the one who oversees the files but makes finding specific documents easier.

The kinds of subject areas you’d choose in this kind of system vary depending on the type of case. For instance, in a personal injury case, you may organize the file according to the following subjects:

- Intake information (client interview; facts investigation; photos)

- Initial pleadings (summons and complaint; responsive pleadings)

- Discovery

- Depositions

- Notices

- Correspondence

- Notes

Subject areas in a domestic relations file would more likely include the following:

- Initial pleadings (summons and petition; custody affidavit; response)

- Temporary orders

- Discovery

- Financial affidavits and support worksheets

- Property division

- Notices

- Correspondence

- Notes

Storing old files

There’s no law that says you have to keep closed case files, because the court maintains the legal record. But there are a few reasons to hang on to old files:

- Closed cases can be valuable reference tools for new cases.

- Old cases may reopen, particularly in domestic relations disputes.

- Sometimes a client requests information contained in an old case file.

So, most law offices keep case files indefinitely, especially if they have the space. To conserve space in the work area and make frequently used files easy to get to, the main file cabinets only contain files for cases in progress. You can scan documents and store them online and/or keep files for closed cases in a convenient location either at the office or in a separate storage facility. In most law practices, the size of the active file system remains constant, but the closed file system continues to grow over time.

Putting together a good time management system isn’t complicated. It just requires an interactive use of simple devices, such as lists, calendars, and records. You can keep track of time with pen and paper or on the computer, but you’ll probably find that a combination of both is the most efficient.

Putting together a good time management system isn’t complicated. It just requires an interactive use of simple devices, such as lists, calendars, and records. You can keep track of time with pen and paper or on the computer, but you’ll probably find that a combination of both is the most efficient. The online content at

The online content at