13

The Subconscious Seduction Model

“Advertisements ordinarily work their wonders … on an inattentive public.”

Michael Schudson

Advertising, the Uneasy Persuasion (1984: 3)

Having now assembled a lot of new learning about how advertising works and might work, you might ask why it is necessary to go to the lengths of building a new model. Why can't we just bolt the stuff we have learned onto the existing persuasion model? The reason I think a new model is needed is that our whole buying environment has changed so much in the last few decades. We have new technology, new ways of interacting with one another, and a huge increase in the number of decisions we have to take each day.

New Technology

It's no use pretending that the world is the same as it was. Take films. Fifteen years ago these were the mainstay of TV schedules. Families would glue themselves to the TV for an afternoon or evening to watch a film. And that gave the advertisers an unrivalled opportunity to expose their ads to us as a group.

Not any more. Films most often come on DVD either from the supermarket or from companies like LoveFilm. We can watch these anywhere (e.g., bedroom, car, kitchen) and any time (e.g., lunchtime, midnight, 3 a.m.) On the rare occasions when there is a film on TV we haven't seen, most of us will record it and play it back at our leisure, fast-forwarding through the ads. And we don't even have to watch it on TV with other people, because we can watch it alone on our own computer. Despite the widescreen and flat screen (and imminently 3D) TV, the era of watching the television together as a group is largely a thing of the past.

Although not entirely. Soaps and reality shows still abound, and these are still the best chance there is for an advertiser to get a good audience. But an audience watching a group of minor celebs in a jungle being bullied into eating insects probably isn't quite the same as a family relaxing together watching a quality film. The sad fact is that advertisers can no longer guarantee that their ad will be seen in a premium entertainment environment by a relaxed and compliant audience.

The New Social Environment

Alongside the change in technology, the social environment in which advertising operates has changed as well. For those of us who live in the West, TV advertising is no longer the novelty it was when it first came out. Indeed, those who were born on the day the first ever TV ad was transmitted for Bulova watches in the USA (July 1, 1941) will have celebrated their seventieth birthday in 2011. And the first TV ad transmitted in the UK was for Gibbs SR Toothpaste on September 21, 1955, so those born on that day will be 56. Only a small minority of us have ever experienced a world when there was no TV advertising, and it shows in the way we disregard it. As Michael Shudson suggests in the quote at the start of this chapter, when it comes to advertising, particularly TV advertising, the vast majority of people believe it deserves scant attention. And that, generally, is what it gets.

It is also undeniable that the marketing environment in which advertising operates has changed. The days when advertisers would trumpet details of their new products on TV are pretty much over. Mainstream TV is a hugely expensive medium to use if you want to go into detail about anything. And, aside from that, any genuinely new product idea is often matched by competitors in less time than it can take to make a TV ad. Take the example of the Dyson DC01 Vacuum Cleaner, which appeared on the market in 1993 with a transparent bagless system that allowed you to see what you were cleaning up off your floors. A revolutionary idea, yet within 6 months, about the time it takes to write, research, plan, and shoot a TV commercial, it is said there were no less than four other brands of transparent bagless vacuum cleaner on the market.

When major product innovations are able to be matched this quickly, what sense does it make to use expensive TV to announce anything but the most revolutionary new ideas? So a direct consequence of the speed with which brands match each other's performance is that TV ads nowadays are used not to “sell” the product but to build positive attitudes towards and relationships with the brand. If you want product details then you can find them on the internet.

It's perhaps worth reminding ourselves what brands are there for. They arrived in the first place as a way of distinguishing one farm's cows from another of lesser quality, and turned into a way of distinguishing one company's products from others of lesser quality. But then it became clear that, far from a simple identification device, brands could be used symbolically to extend and enhance what the company was offering. And this became a two-way benefit, because we, the consumers, found we could use brands as a way of shortcutting the onerous task of deciding what to buy.

This is very effectively illustrated by an experiment which I alluded to in Chapter 3, conducted in 2000 by Stijn Van Osselaer and Joseph Alba (2000). Van Osselaer and Alba devised a pair of imaginary brands of inflatable boat, each with a range of different product attributes. They then exposed different groups of students to these product attributes, which gave them an indication of how people behave when buying unbranded products. What they found was that the students examined the attributes until they were satisfied they had established which of them signified quality, then ignored all the others. All as you might expect.

They then looked into what happened when they exposed the subjects first to the branded boats. Their view was that brands “signal” quality but do not “prove” quality, so when product attributes that prove quality are available then people should ignore the brand and revert to studying the product attribute. But this isn't what happened. When brands were exposed first the students quickly formed a preference, and then instead of examining the product attributes to find out which signified quality, they simply examined enough to support their brand preference. Consideration of all the other product attributes was effectively “blocked.”

The idea that the mere presence of branding may inhibit our learning behavior from attributes in this way seems at first to be counter-intuitive. We like to think of ourselves as logical humans who behave in a logical and deductive way. The problem is that we don't live in a world where we have enough time available to allow us to be logical and deductive. Most of those who live in developed countries lead busy lives where shopping is an activity that has to be integrated with and around activities like looking after our spouses, our children, our houses, and consuming media. And what compounds our problems is that when we do decide to buy something we find ourselves offered an ever-increasing range of items to choose from.

The Tyranny of Choice

I can still recall my first sight of the canned tuna fixture in the Sainsbury's supermarket in Greenford in 1999. The fixture was roughly 20 feet long, and contained an almost endless variety of big round tins, small round tins, small oval tins, and large oval tins. These contained anything from tuna chunks to tuna steaks to tuna slices to tuna fillets, and the type of tuna varied from ordinary tuna to skipjack tuna to “South Seas” tuna to yellow fin tuna, and these were available in anything from brine to sunflower oil to olive oil to tomato sauce to mayonnaise to mustard sauce, and so on. And all this was merchandized under four or five different brand names.

Finding this choice bewildering, I decided on a simple strategy, which was to choose a brand that claimed to be “dolphin-friendly”: except I swiftly discovered that all the brands were dolphin-friendly. And that's the problem. Nearly all reputable brands offer exactly the same thing.

This is exactly the state of “ultimately unsatisfying and psychologically draining … hyperchoice” which we discussed in Chapter 3. And this, of course, is why Van Osselaer and Alba found their students using brands as an excuse to “block” the study of product attributes. It has become the new human nature for us to seek for shortcuts that save us time and effort. And we don't just do this in trivial product categories. Take the onerous task of choosing a new washing machine. It is said that a broken washing machine is rated as one of the most stressful situations that can happen to us (behind divorce and house-buying), so not surprisingly the single overriding property that everyone seeks when buying a new one is reliability. But go into a store looking for a washing machine and you'll find a bewildering variety of program types, spin-speeds, green credentials, and prices, but not a single claim or shred of evidence regarding how reliable a machine is. Hardly surprising that Gerard Tellis finds that “Contrary to popular perception, many consumers do not resort to active search, even for expensive and infrequently purchased products” (Tellis 1998: 121).

So how do we go about making decisions in this confused “hyperchoice” world? The answer is that we rely on Damasio's route B, the “covert activation of biases related to prior emotional experiences in comparable situations.” This, of course, is what Damasio identifies as “gut feeling,” or intuition.

Intuition

The Oxford Dictionary defines Intuition as “the ability to understand something instinctively, without the need for conscious reasoning.”1 And that's how we feel when we use our intuition: we understand which product to buy even though we can't rationally explain why. In reality, the reason we think we understand what to buy is that over our lifetime we have laid down hosts of emotional markers that are now resident in our subconscious and capable of being covertly activated.

Here's an example of how intuition works. At some time in our life we have a friend whose washing machine breaks down on them with traumatic results, and they blame the breakdown on the fact that they bought a cheap washing machine made in Country X. Quite soon you forget this, but it creates a subconscious marker in your mind against cheap washing machines made in this particular country. So when you next need to buy a washing machine you find inexplicably that you avoid those brands made in Country X, and those brands that are especially cheap.

Indeed, as with Van Osselaer and Alba's students, you don't really look very hard at any of the other brands, because what you feel you want to buy is a Bosch. And why do you intuitively want a Bosch? Because another marker makes you feel that German products are the best engineered in the world, and therefore most reliable, and the word Bosch could not be more German!

Of course, it helps that the Bosch machines are a bit more expensive than all the other brands. Why? Because the marker in our minds that tells us not to trust cheap washing machines makes us especially vulnerable to slightly more expensive washing machines. And it helps even more that the Bosch is being offered at 10% off regular price, because that makes it only a little bit more expensive than the other brands. Mind you, it's only able to offer 10% off its regular price because countless other people are doing the same as you and intuitively choosing a Bosch washing machine.

Mostly, this sort of intuitive decision-making happens without our being aware of it. And it is commonplace, not exceptional behavior. That's not to say that the marketing establishment accepts that it goes on. John Bargh laments that:

Although in the past decade of consumer research there has been increasing attention to the possibility that there may be automatic or nonconscious influences on choices and behavior, the field still appears dominated by purely cognitive approaches, in which decisions and actions are made deliberately. (Bargh 2002: 280)

So in many respects the sort of decisions we make regarding which washing machine we buy might have already been made for us before we set foot in the shop. This is the extent to which we are prey to external influences. Of course, advertising hasn't really played a part in this washing machine scenario, but it is easy to show how it can.

“Along comes an ad …”

So there you are, slumped in front of the TV watching a repeat of Friends or Desperate Housewives or some other show, when the ad break comes on. Let's assume you're too lethargic to go and make tea or change channel, so you just sit there. TV is known to induce a sort of trance-like lethargy in most of us: I recall Bruce Goerlich saying, in defense of the 30-second TV ad, that “There are a lot of consumers coming home in the evening, taking their brain out and putting it in a warm bowl of water, and watching television.”2 That is what we watch TV for, to relax and not to have to think too much.

Being in this sort of lethargic state means your attention level towards the TV is not going to be that great. And given that we don't expect to learn anything of great importance from TV advertising there isn't going to any motivation to increase it when the ads come on. Nevertheless, when an ad starts you'll either recognize it as one you've seen before or not. (Remember, Lionel Standing's picture experiment showed our recognition powers are prodigious.) If you do recognize the ad as one you have seen before, your attention level will almost certainly fall even more, because you will know instantly there is nothing new that you will learn from it.

So let's assume you don't recognize the ad, and that it isn't for something that you are desperate to buy. As the ad proceeds you register a stream of perceptions and these trigger a stream of concepts. All this happens automatically and subconsciously. Periodically you'll see or hear something that might get you to actually pay a little bit of attention and do some analysis. Typical amongst the things you pay a bit of attention to is the identity of the brand being advertised (note that I say “identity” because often it is a logo, not a name, that alerts us to the actual brand). Why should we want to pay attention to this? Simply because it is instinct to want to decode what is passing by our eyes and ears, and we know that no ad makes sense unless you know who it is for. But, in line with Dennett's hypothesis, the likelihood is that the period of attention will be short and the brand name will roll briefly into consciousness and then be swiftly forgotten.

I think ad agencies are rather stupid when it comes to deciding where to put the brand in an ad. They worry that if they put it in early on then you'll realize who the ad is for and mentally switch off. So they often put the brand right at the end of the ad, thinking that we will pay attention to find out who the ad is for. Sadly for them, most of us will switch off pretty quickly if we don't find out fairly soon what the ad is advertising, and by the time the brand arrives at the end we will probably have forgotten what little we absorbed about what the ad was trying to say about it.

Occasionally, our curiosity does lead us to attend sufficiently for us to understand the message the ad is trying to get over. If we do this then the message will do one of two things: it will either generate a set of beliefs, which might then change our attitudes; or it might change our attitudes directly. If there's no incentive to remember these changes (e.g., they're predictable, banal, or just plain unexciting) then we might perceptually filter them out and forget them instantly. If we pay a lot of attention to them, we might counter-argue them and decide they are rubbish.

If the ad does get an interesting message into our head and change our attitudes, there may well be an increase in likelihood that we might at some stage in the future buy the brand. But, with perceptual filtering, counter-argument, and general lethargy, most ads will fail to register any rational message for longer than a few seconds after the ad has finished.

As I said earlier, if this ad is one we have been exposed to before, the chances are that we will pay less attention than we did the first time. Our analytical faculties will therefore be even less engaged and the likelihood of us interpreting or recalling a message even smaller. Of course, should the ad mention something that is genuinely “new,” and therefore of interest to us (like an especially low price for a car, sofa, or holiday, or an interesting or important website, etc.), then there is a much better chance we will remember it. But in general there is only a very small chance that a TV ad will get us to pay attention to the sort of predictable rational messages in most ads. It is too easy to dismiss as hogwash claims like “our product is the best on the market,” or “it tastes good because we use only the finest natural ingredients,” or “we guarantee satisfaction or your money back.”

But there are other consciously processed elements that stand a better chance of sticking in our mind. If the ad consistently and repeatedly uses a slogan, or shows a well-known character, a unique drawing or design, or a particular sequence of events, you will, even in a lethargic state, associate it with the brand over time. A well-known example is the Intel jingle. It comprises four notes, the first and third the same, the second higher and the fourth higher still. Practically everyone in the world recognizes it, because it is played in the advertising of every computer that uses an Intel microprocessor.

These associations can be incredibly long-lasting: many people in the UK still recall slogans like “Keep going well, keep going Shell,” “Go to work on an egg,” and “Guinness is good for you,” even though they are half a century old.

To demonstrate this to yourself, try filling in the brands in these US ads: “Just do it,” “We try harder,” and “That'll do nicely.” Or if you live in the UK, try “Beanz meanz … ,” “I bet he drinks … ,” and “Liquid Engineering.” I've no doubt you found that surprisingly easy.

What, if anything, do these slogans achieve? To understand that we have to leave the conscious and look back into the subconscious.

Subconscious Associative Conditioning

Let's go back to the stream of perceptions and concepts you get when you are exposed to an ad. As we've discussed already, these occur throughout the advertising, because we can't switch them off. So every element of an advertising campaign that gets stuck in your mind brings with it a whole raft of concepts. And this is axiomatic: as Watzlawick states, every “digital” communication element has a corresponding “analog” metacommunication concept riding on its back.

Sometimes these concepts are emotionally sterile. The Intel jingle, for example, is purely a branding device and conveys little in the way of conceptual values. Using Damasio's terminology, it is an example of an emotionally incompetent association. But most communicate rather more. For example, Papa and Nicole in the Renault Clio ad trigger the concepts of style and sexiness; the Andrex Puppy triggers the concepts of family values and softness; the British Airways music triggers the concepts of relaxation and contentment; the drum-playing Cadbury's Gorilla triggers the concept of liberation; and the Hamlet Cigar music triggers the concept of consolation. And in each case these emotionally competent associations, exposed repeatedly, condition us to feel the brand being advertised has these same emotional values.

Just occasionally we become actively aware of these conceptual emotional associations (e.g., when someone from a market research company asks us what we associate with puppies). In most cases they remain hidden away in our subconscious. There they act in the same way as Damasio's somatic markers: when we come to make a decision, they are able to covertly influence how we make that decision. They also operate as a subconscious gatekeeper if we try to make a decision that goes against them. And, if we are in a hurry to make the decision, they can drive our intuition, and effectively make the decision for us. We can illustrate the influence of these associations using the case study of the famous Michelin Baby Campaign.

Michelin Baby Campaign Case Study

In 1984, Michelin appointed the ad agency Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB) to handle their advertising. DDB had the idea of using babies in their advertising, along with the slogan “Michelin, because so much is riding on your tires.” Michelin ran advertising featuring babies for 17 years, until someone in their marketing department presumably decided either that people were getting bored with them, or (more likely) that they didn't say enough about the actual tires. Either way, the account was put up for review in February 2001 and DDB lost it. The last baby ad ran in April 2001, advertising Michelin's victory in the J.D. Power Customer Service awards.

One of the most moving of these ads featured a baby sitting in a car tire, with a large rather shaggy dog sitting next to it. In the background is playing a fake weather forecast, predicting that the unseasonably warm weather might turn into “severe thunderstorms and localized flooding” then “snow, turning to freezing rain.” As we hear this, the dog goes off screen and returns wearing a yellow oilskin and carrying one of her puppies (also dressed in a yellow oilskin) by the scruff of the neck. The dog gently deposits her puppy into the tire alongside the rather confused-looking baby.

During the two decades that they ran, these ads strengthened Michelin's brand image year after year. Not just amongst women with babies, but amongst the population as a whole. How did they do this? Well, simply seeing a baby triggers the concept not only of cuteness but of extreme vulnerability, which in turn triggers the concept of safety. Thus, without the need for any rational product performance claims, the baby conditions us to associate Michelin tires with safety. In the absence of any good reason to buy another make, this marker would exert sufficient influence on our choice of tire to make us favor Michelin.

But mostly we purchase tires after we have a blowout, or when we are told that our tires are no longer legally roadworthy. It's what is called a “distress purchase,” and as such means we have to make our minds up fast. In situations like this, Damasio predicts our intuition will drive the decision directly. And what drives our intuition? Why, the baby marker that has conditioned us to believe that Michelins are the safest tires. So that's what we buy.

Subconscious associative conditioning like this can be extraordinarily long-lasting, partly because it is subconscious and so is never counter-argued. In the case of Michelin, a Goodyear case study written some 6 years after the baby campaign ended stated that:

Despite being off the air for years, Michelin's “baby” campaign firmly associated them with safety. According to Millward Brown brand tracking data, Michelin led Goodyear in 2006 in overall opinion and purchase consideration, and had significantly higher ratings on important attributes such as trusted brand and high quality.3

So one way that TV advertising can influence us while we sit there in our lethargic state is by subconscious associative conditioning. But there's another subtly different way that advertising can influence us subconsciously, and that's by manipulating our relationship with the brand. This is especially the case with TV advertising.

Subconscious Relationship Manipulation

Most of us don't mind TV advertisements. They are, after all, usually designed not to be too offensive. We don't necessarily find them actively entertaining any more – research shows this has nearly halved over the last 20 years – but we mostly don't find them all that annoying either. And we know that TV advertising pays for our TV channels, and is something we should therefore really not complain too much about.

Because we don't mind TV ads, and we don't expect them to tell us much that is new, we let them run by with fairly good grace. Sometimes they are beautifully made, play lovely music, tell us nice stories, or show glorious countryside. Occasionally they are quite funny and entertaining. So as long as we don't let ourselves be seduced by their message, what could possibly be wrong with watching them?

The answer is nothing, provided you don't mind your relationship with the brand being subconsciously manipulated and your attachment to it being subconsciously increased; because mostly this is what is happening. The 2006 Dove Superbowl advertising is an example.

Dove Self-Esteem Fund Case Study

Dove is well-known for its quite outspoken advertising campaigns. Their “Campaign for Real Beauty” and their “Pro-Age” campaigns are just two examples.

In 2006, as part of their Campaign for Real Beauty, Dove decided to found the Dove Self-Esteem Fund, as an “agent of change to inspire and educate girls and young women about a wider definition of beauty.”4 In support of this move they made a TV commercial and ran it at the 2006 Super Bowl. Using the Cindi Lauper hit True Colors as a background, the ad showed a sequence of cameos of girls of ages ranging from about 7 to 10 looking really depressed and miserable, and then the same girls looking happy, invigorated, and confident.

Of course, many people are very cynical about ads like this, and at a conscious level they would counter-argue the brand's involvement, saying things like “I bet they spent more money on getting the ad into Super Bowl than they gave to support the kids.” But the ad, showing the transformation of the young girls from miserable to happy, and playing the beautiful music track, is very moving and has a terrific feel-good factor about it. And research confirmed that, unlike the vast majority of Super Bowl ads, 92% of people liked it and 93% found it emotive.

So no matter how much you consciously reject their motives, the ad does make you feel good about Dove, and will enhance your attachment to the brand. You don't have any option, because the only defense you have against this is your rational counter-argument. It's like watching someone cry in the movies: it doesn't matter how much you tell yourself it is a film, your mirror neurons will make you feel sad.

And there are two further things worth bearing in mind. The first is that you will only consciously reject the Dove Self-Esteem Fund ad if you paid sufficient attention to it. The second is that your conscious mind is incredibly busy and not that capacious. So, as we showed in Chapter 5, it is likely that the connections to your cynical counter-arguing rejection engram will be overwritten by you and forgotten pretty swiftly. But the feelings generated about the brand are held subconsciously in your inexhaustible implicit memory, and you are unable to overwrite the connections. So the improvement in your relationship with Dove will be with you forever, or at least until some negative metacommunication comes along to give you a bad feeling about them.

What is being revealed here is that advertising can, simply by exposing us to emotive content that makes us feel good alongside a fleeting exposure to a brand, affect our attachment to that brand. And this emotive content doesn't have to be stuff that makes us laugh or cry; it can be background music that is uplifting or nice to listen, or people expressing their emotions (love, anger, excitement, boredom, curiosity, appreciation, amusement, etc.), or situations that are humorous or poignant or dramatic, or scenery that is elegant or beautiful, or even just footage that is just beautifully shot with high production values.

So how much does this matter? Well, it wouldn't matter at all if every brand on the supermarket shelf was manifestly different from all the others. If that were the case then our choices would be based on what the brand does not how we feel towards it. But, as we discussed earlier in this chapter, most brands are not that different from each other nowadays, and virtually all brands satisfy our needs perfectly well. In these circumstances how we feel about a brand can become the way we choose a brand.

And even if the brands are different in some important way, bear in mind Damasio's model of decision-making, which showed that our emotions act a gatekeeper in influencing our decisions. We are simply unable to make rational decisions without our emotions concurring. So if it comes to a choice between a brand that has no particular defining character, and one that we feel good about, the odds will be stacked in favor of the latter. The bottom line is that all those apparently innocuous images we see in advertising are what in many cases are driving our behavior.

The Subconscious Seduction Model

So here is my recipe for the alternative way in which TV advertising in the twenty-first century influences us:

It starts with emotive metacommunicating content. That may be emotion that is present throughout the ad itself and influences the way we feel about the brand (as in the Dove Self-Esteem Fund), or it may be emotive values that attach to a component of the ad and that become associated with the brand and so condition it to have the same emotional value (as in the Michelin Babies and the Andrex Puppy).

We generally like positive emotive content, and we generally trust what we like. We don't tend to pay much attention to ads (especially TV ads) and one of the main reasons we do feel the need to pay attention is when we want to counter-argue what they are telling us. The more we like and trust an ad, the less inclined we are to counter-argue its message, and the less attention we feel we have to pay towards it.

As Bornstein found, the lower the level of attention we pay to an ad or to a component of an ad, the less we are able to counter-argue it, and the more the ad is able to influence our emotions.

The more the ad influences our emotions, the better it is able to condition the brand to have that emotion and create positive brand relationships. These conditioned associations and positive relationships make use feel more favorable towards the brand.

One of Watzlawick's key findings was that although the content of communication (i.e., the messages in an ad) fades and vanishes quite quickly, the subtle emotive brand attitudes generated by the emotional metacommunication are safely tucked away in implicit memory, and these will endure for a very long time.

So at some time in the future when it comes to a purchase choice in which there is very little to choose between two brands, we will intuitively choose the one we favor. And because we don't remember how we formed the attitudes and markers that created this intuitive feeling, we can't easily prevent it from influencing us.

This also explains why we all have so much difficulty remembering ads. The details of the ads themselves fade quite fast, because these are complex pseudo-episodic memories whose recall pathways can easily be blurred and overwritten. And any rational message content in TV advertising, which we've already established we don't pay much attention to anyway, will also fade as quickly as the memory of the ad itself. But the emotional metacommunication memories that influence our feelings toward the brand will endure much longer. And we may have not the slightest inkling that they are there.

Decision and Relationship: Summary

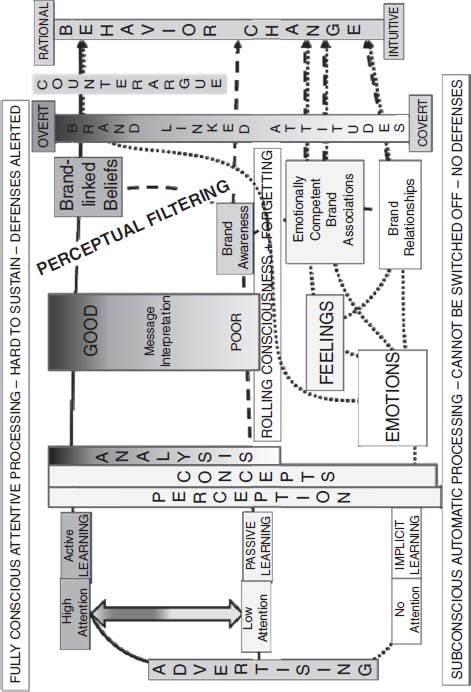

We now have a complete chart of the new Subconscious Seduction Model (Figure 13.1), and it shows a number of important additions. For example, Brand-Linked Attitudes are qualified now according to whether they are Overt (i.e., those we are aware of and able to recall) or Covert (those we are not aware of and would have difficulty recalling). Behavior Change is also now qualified by whether the behavior is Rational (i.e., based mostly on reasoning) or Intuitive (i.e., based upon feelings or markers stored in the mind from past comparable experiences).

Figure 13.1 The Subconscious Seduction Model

The first thing to point out is that a dotted “emotion” lines now joins the solid “persuasion” line in driving Rational Behavior. This reflects emotion's role as a gatekeeper in decision-making. As we saw in Chapter 11, we cannot make decisions if our emotions do not concur with them.

The second thing is that overt attitude changes and rationally driven behavior are both able to be counter-argued. This means that the top half of the model depicts a state in which we have our defenses against advertising alerted. Conversely, the bottom half of the model depicts a state in which we have little or no defense against advertising. It is almost impossible for us to defend ourselves against covert attitude change and intuitively driven behavior. In the case of covert attitude change we are unlikely to be aware that our attitudes have changed unless someone subjects us to hypnosis; and in the case of intuitively driven behavior we are unlikely to know exactly what is driving our intuition.

So anything operating towards the bottom of the model is going to be able to exert an influence on us which we won't find very easy to resist. The first of these “lower level” influences is the box marked Emotionally Competent Brand Associations.

Three influences – Brand Awareness, Feelings, and Emotions – all converge into this box marked Emotionally Competent Brand Associations, which lies a little way up from the bottom. The reason it is positioned here is that these are entities like the Andrex Puppy and the Marlboro Cowboy that are not themselves covert, but are known and often well recalled as being linked to brands. What isn’t so well known, however, is that these devices are Emotionally Competent Stimuli (ECS) which trigger potent and relevant emotional concepts, and on repeated exposure “condition” us to feel that the brand has the same emotional values as the entity. Thus, the Andrex Puppy conditions us to feel that Andrex is both soft and family-oriented; and the Marlboro Cowboy, as we will see in Chapter 16, conditions us to feel that if we smoke the Marlboro brand then people will see us as being tough and independent. In this way they change our attitudes towards the brand in a covert way, without us realizing they have done so.

At the bottom of the model is the Brand Relationship box. The creativity in advertising is able to influence both our emotions and often our feelings, and these in turn can influence our brand relationships via metacommunication. This again mostly happens covertly: most of us are not really aware that we have feelings for brands, let alone that a piece of music played in an ad, for example, will be influencing them. It just isn't the sort of thing we tend to think about or talk about.

Well, a model is one thing. How much this really has an effect on us is a much more important question. And that is answered in the final part of the book.

1. http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/intuition?view=uk

2. Verbatim quote by Bruce Goerlich, Executive Vice President of Zenith Optimedia, at the lunchtime panel of the Advertising Research Foundation (ARF) Conference, April 17, 2007.

3. http://s3.amazonaws.com/thearf-org-aux-assets/awards/ogilvy-cs/Ogilvy_08_Case_Study_GoodYear.pdf.