The Rorschach Tree: Baobab

THE FIRST TREES TO BE REGARDED as prodigiously ancient by European explorers were the baobabs of Africa. Baobabs evolved on Madagascar, which was cut off from mainland Africa more than 100 million years ago, and became a cauldron for the development of bizarre organisms. Ninety per cent of the island’s plants and animals grow nowhere else on earth – lemurs most famously, but also three-quarters of its 850 species of orchid. There are six aboriginal species of baobab here and all are adapted to living in the parched soils of the Madagascan savanna. They have waxy white flowers which are pollinated by moths, bats and even bush babies, which have been spotted eating the petals and playing with the powder-puff stamens. To conserve water they have evolved dwarfed crowns, short branches and leaves which drop early in the dry season. When the trees are young, these flat, foreshortened topknots look like roots. A local myth explains this by suggesting that the primordial baobab was too beautiful for its own good. The gods turned it topsyturvy as a punishment for vanity, and for good measure endowed it with cumbersome portliness.

But what chiefly keeps baobabs alive in the drought months are the paunches and elephantine buttresses that develop on mature trees. Their trunkwood is as soft and absorbent as balsa, and becomes a living cistern, capable of storing thousands of gallons of water. What is uncanny is how often baobabs resemble human water vessels – not just vaguely, but in the exact detail of accommodating barrel and narrowing neck, as if there are physical imperatives underlying the design of all liquid containers. Early Africans’ own crafted vessels may not have needed the inspiration of baobabs, but it is easy to see how both species reached common solutions to the challenge of holding in a volatile, mobile material. There are baobabs reminiscent of pitchers, chamber pots, petrol cans and superior magnums of wine. At Ifaty on Madagascar, a specimen of Adansonia za is a gigantic three-dimensional cartoon of a canteen teapot, complete with an upwardly pointing spout. I suspect that Vermeer, whose paintings of interiors are adorned with the fluid curves of jars and jugs echoing those of their human users, would have been intrigued by the baobab tree, the vegetable pitcher and paunch.

At some point in the last 10 million years the seeds of one of the ancestral baobab species, which are cosseted in large buoyant pods, floated out across the Mozambique Channel and fetched up on the East African mainland. The seeds germinated, and the resulting trees evolved over millennia into a seventh species. Adansonia digitata proved to be the most adaptable and successful of the genus, and soon spread across the continent, eventually helped on its way by local people, who found it an inventive, accommodating and adaptable companion. In 1832, in the early stages of his voyage on the Beagle, Charles Darwin was shown a great baobab on the Cape Verde islands, 300 miles west of mainland Africa. It was reputed to be 6,000 years old, and Darwin carved his initials on it, though can’t have believed this figure. Old trees like this often become hollow, at which point they may be dragooned into service as village reservoirs – a water tank inside a watery shell.

It was in mainland Africa that the baobab met its mammalian doppelgänger. Elephants (absent from Madagascar) homed in on these suggestively pachydermic invaders. They attacked them with a ferocity that seemed to go beyond the simple satisfaction of big appetites. They trashed them. They tore off whole branches, devoured the leaves, stripped the bark entirely from the lower parts of the trunk to reach the moisture underneath, and often knocked the smallest trees flat. However, the baobab had already evolved adaptations to rough treatment in the bush fires of Madagascar. When damaged or stripped, by whatever agency, the bark grows back, just as it does on stripped or burnt cork oaks. The fallen trees simply continue growing where they lie, building wooden boulders out of their wrecked trunks, pushing up new columns, snaking out new limbs parallel with the ground. One famous heap of a tree close to the Limpopo in South Africa is known locally as ‘Slurpie’ – an affectionate reference to the baobab’s complex relationship with elephants, as both victim and mimic. It’s an abbreviation of Olifantslurpboom, meaning ‘Elephant Trunk Tree’.

This plasticity of form is the most remarkable feature of baobabs; they are shape shifters. They can swell, shrink, curl, explode, creep about. They can begin their lives as Palladian columns, be blown down, set on fire, and then regenerate from the wreckage as a coil of snakes or a lava stream or a cave mouth. Human strangers who have witnessed their protean powers have been inspired to protean dreams.

In 1749 the young French naturalist and traveller Michel Adanson, away on an exploration of the coast of Senegal, canoed out to the island of Sor. He had planned to hunt antelope, but was stopped in his tracks by a different kind of trophy, immense, immobile, uncatchable. ‘I laid aside all thoughts of sport,’ he wrote in Histoire naturelle du Sénégal, ‘as soon as I perceived a tree of prodigious thickness, which drew my whole attention … I extended my arms, as wide as I possibly could, thirteen times, before I embraced its circumference; and for greater exactness, I measured it round with a packthread, and found it to be sixty-five feet.’ It was a baobab, and Adanson was transfixed by its mass and gravitas. He later found trees with girths over seventy-five feet, and concluded that ‘as Africa may boast of producing the largest of animals, viz. the ostrich and the elephant, so may it be said, not to degenerate with regard to vegetables, since it gives birth to calabash trees, that are immensely larger than any other tree now existing, at least that we know of’. He soon began to suspect that they were also the oldest trees on earth. Deep in the interior of Senegal he found baobab trunks inscribed with the names of European settlers from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the letters of the signatures still legible, and barely stretched beyond the original knife marks. In the compelling fixity of these graffiti, which seemed immune to the ravages of time, Adanson thought he saw evidence of organisms whose laborious growth had begun maybe 5,000 years ago, before the Flood.

This was a heretical thought for the time, and outraged a later Africa hand, the staunchly Christian Dr David Livingstone. In Missionary Travels (1857) Livingstone wrote: ‘Though it possesses amazing vitality, it is difficult to believe that this great baby-looking bulb or tree is as old as the pyramids.’ Making a rough estimate of the annual growth rings (they are indistinct in the species), he reckoned that a tree one hundred feet round would be only 1,400 years old. Modern measurements, using radioactive carbon dating, have confirmed that baobabs rarely reach one fifth of the age Adanson imagined. Their awesome bulk had persuaded him to see them as primeval.

So here was a classic Enlightenment encounter between plant and imagination. A wide-eyed, twenty-two-year-old naturalist dowsing ancient texts carved in the living body of a tree. Adanson was a precocious and irreverent young man. Thirty years later he would compile 150 volumes covering the entire array of creation as it was then known, and see them politely ignored by publishers. His ambition was to find, or make, order in a natural world he saw as ‘a confused mingling of beings that seem to have been brought together by chance’. In the encrypted, living monoliths of Senegal – the genus was subsequently dubbed Adansonia in his honour – he had glimpsed the chaotic enormity of biological space and time, and maybe his own intellectual fate. What the baobab’s capricious inventiveness represented would always triumph, however much he tried to regiment and unmingle it.

It’s no wonder that the biggest and oldest trees have become places. Their eccentric bulk makes them obvious landmarks, sites for village meetings and religious rituals. Recently their tendency to become hollow has been exploited for more mundane utilities – bus shelters, storerooms, occasional refuse dumps. One in South Africa has been turned into a rather smart pub, with a lantern-lit bar and naturally water-cooled cellar inside. In Senegal, villagers once buried their dead in the hollow trunks, and there is no disrespect seen in these contrasting sacred and secular uses. In nearby Burkina Faso, the death of a baobab is itself commemorated by a full-dress communal wake. The trees aren’t regarded as gods or wreathed by unbreachable taboos, though they are seen as providing resting places for ancestral spirits. When a number of revered baobabs in Zambia were due to be flooded by the creation of the Kariba dam, the locals ‘evacuated’ their resident spirits by lopping branches from the doomed trees and attaching them to other baobabs outside the flood zone.

Ancient baobabs are looked on as arboreal village elders. When they die, they are mourned like dearly departed citizens. The West African writer and storyteller Seydou Drame has described just such a wake for the Baobab of Kassakongo: ‘One day its leaves failed to grow again. Still upright, the old wooden elephant had given in to death, and so it was the whole village prepared for its funeral … The chief tells the story of the tree’s life as if he were talking about an old man who had just died. “He chose to take up residence in Kassakongo. The villagers took his presence as a blessing from God.”’

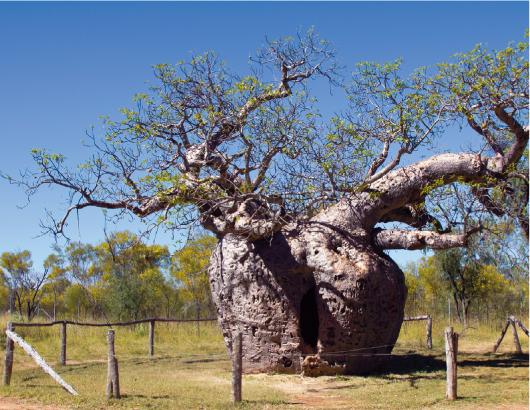

The ever-buoyant pods of Adansonia digitata eventually bobbed (or were boated) all the way across the Indian Ocean to Australia, where their descendants evolved into a very similar eighth species, A. gregorii. In the Herbarium at Kew there is a virtual chart of its colonisation of north-central Australia in the specimen sheets of nineteenth-century botanists, as they themselves edged through the unexplored wilderness. The difficulties involved in mounting thick twigs and fragments of fruit on flat sheets in the field (and often in the dark: some of the sheets are black with soot from oil lamps) hasn’t stopped the insistent diversity of this species showing through. Different specimens from isolated valleys in Kimberley have distinctly different leaf shapes and patterns. This diversity – and the presence of what appear to be images of baobabs in the remarkable and atypical ‘Bradshaw’ rock art of Kimberley (dated to about 15,000 to 18,000 BC) – has encouraged some scientists to speculate that various baobabs were brought to Australia deliberately, during transoceanic human migrations from Africa 60,000 years ago. As is always the case when plant migration and cultural origins are entangled, this is a highly contentious theory, which runs counter to the orthodox view that Aboriginal culture sprang from a single colonisation by South East Asians maybe 50,000 years ago. Genetic fingerprinting of the Kimberley baobabs may soon establish the date of their arrival and how closely they’re related to African trees. But it is unlikely to resolve whether they floated over of their own accord or were carried in reed boats by Palaeolithic San explorers.

Either way, A. gregorii has been thoroughly naturalised, to the extent that it has its own Australian vernacular tag of ‘boab’ (and just occasionally ‘boob’). One distinctive specimen has an especially sad and strange history. The Prison Boab near Derby Harbour in Western Australia has grown into the shape of the pots in which missionaries were supposedly cooked by cannibals. Legends testifying to a rather different history weave about it. It may have been an Aboriginal burial site, then, in a dark reversal consequent on European colonisation, a place where Aboriginal prisoners, chained together, were lodged during the last stage of their journey to the local courthouse. When the explorer Herbert Basedow combed through the litter inside the trunk in 1916, he found bleached human bones and a skull with a bullet hole. The outside of the tree is riddled with graffiti and autographs, a globe-shaped rune whose origins and meaning are unlikely ever to be deciphered.