Provenance and Extinction: Wood’s Cycad

IN THE CASE OF ONE INDIVIDUAL from an ancient tree lineage, cloning was the last option if the species was to survive. Only a single specimen of Wood’s cycad, Encephalartos woodii, has ever been found in the wild, in Natal in 1895. It died as a result of repeated mutilation seventy years later while in intensive care in a government enclosure in Pretoria. Luckily a few offsets from the main stem had been despatched to a handful of botanic gardens, including Kew, before its demise. Wood’s cycad is dioecious, and has male and female reproductive structures on different plants. Since no female has ever been seen, cloning from offsets is the only way Wood’s cycad will survive as a true species. Its decline underscores the poignancy of extinction, but at a deep cellular level is also a heartening parable about the tactics plants employ to avoid such extreme events, and how humans can intervene to help.

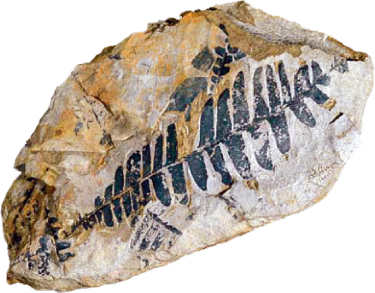

The cycads are the one of oldest orders of trees. They evolved about 280 million years ago, in the wake of the Carboniferous coal forests, and flourished throughout the reign of the dinosaurs, their lush evergreen leaves providing very desirable forage. They resemble palms in their topknots of divided leaves and scaly trunks, but, as prototypes of the various kinds of plants that were to follow, they have reproductive organs which are a kind of compromise between a flower and a cone, known scientifically as strobili. The male cones of cycads can be huge. E. woodii’s is a yellowish cylinder which can grow up to three feet in length, its spiralling scales giving it something of the appearance of a stretched pineapple. It produces an abundance of pollen, which is carried to the female strobilus – not a cone, but a large cluster of woolly leaves – by beetles and weevils. In the Jurassic era this may have been one of nature’s first experiments in symbiosis between plant and insect. It was a successful experiment, and the descendants of those first pollinators would have been primed to perform the same services when flowering plants arrived on the scene.

Cycads continued to thrive during the Jurassic, and spread globally throughout the tropics and subtropics. They are still widely distributed, across South East Asia and the Pacific, the southern half of Africa and South and Central America, where the greatest diversity occurs. More than 300 different species have so far been described (new discoveries are being added all the time) and they occupy every kind of habitat, from rainforest to semi-desert. For such primitive plants, they are wonderfully resourceful, which is perhaps the reason they survived the ecological catastrophe that put paid to the dinosaurs. There are adaptations for every kind of contingency. If pollination fails they can sprout vegetatively from the base by offsets and suckers. The growing shoots are protected by fire-resistant basal leaves. They have unique ‘corraloid’ roots which live in symbiotic partnerships with algae able to fix atmospheric nitrogen – a trick which the bean family also achieved but 100 million years later. Their seeds are huge and surrounded by layers of nutritious husk, but have an inner seed kernel impervious to even an elephant’s digestive system. The seeds of some species can float, possibly over whole oceans, like the baobab’s. They also, as a family, have a strong propensity to throw up new subspecies and hybrids, adapted to quite specialised niches, providing yet another route to survival and the colonisation of new territory.

But the life of a fine-tuned, highly local species is also precarious, not suited to sudden changes in its environment. E. woodii was one of these vulnerable endemics. The only known wild individual was a cluster of four stems discovered in 1895 by John Medley Wood, curator of the Durban Botanic Garden, growing on a steep, south-facing bank on the edge of oNgoye forest in Natal. A basal offset was removed and sent to London’s Kew Gardens in 1903, where it has grown in the Temperate House ever since. Aware of the tree’s knife-edge existence, botanists took more basal cuttings over the following decades, and sent them to botanic gardens in Durban and Ireland. By 1912 there was only one short and damaged stem of the original plant left in the wild. The priority of conserving a species in its wild habitat wasn’t properly understood at the time, and four years later the Forestry Department arranged to have this last surviving specimen dug up and sent to the Government Botanist in Pretoria, where it expired half a century later. E. woodii has consequently been officially granted the dubious honour of ‘Extinct in the Wild’ status.

Currently offsets from the Durban and Kew trees are growing in other botanic gardens across the world, an example of the curious but expanding process of the democratisation of rarity. Kew’s specimen, now more than a century old, will be a star feature of the New Temperate House to be opened in 2015. Meanwhile it lies huddled in a corner in the original building, shorn of its fronds, as these had grown too big for the plant to get through the door – a cutting down to size that seems to echo its past history. But Wood’s cycad will never reproduce naturally unless a female is discovered, so current attempts at propagation rely chiefly on the fact that its pollen will generate fertile hybrids from its close relative, E. natalensis. If these offspring are repeatedly back-crossed with E. woodii, a progeny may eventually arise that will show roughly what a female E. woodii looked like in the wild, echoing the scientific dream that woolly mammoth hybrids may be brought back from the dark world of the extinct by inserting fragments of fossil DNA into elephant genes. Our sense of ‘the natural’ warps here. The thrill of Promethean creation, of a pathway to reparation for the damage we have done to the natural world, crashes into an ancient Frankensteinian guilt and a simple longing for a world beyond our planning. But these things will happen and we need to learn how to think ethically about them.

Worries about the individuality of ancient plants are especially acute with trees. Their age and singularity give them something of the aura of living artworks, and provenance and authenticity become issues. In America the seniority of coniferous Methuselahs is fiercely contested. In Britain communities make claims and counterclaims about whose oak a displaced monarch or fleeing dissenter once hid in. The trees themselves are fenced and proclaimed on ornamental plaques like military heroes. Hybrids between native rarities and more vigorous intruders are despised and sometimes destroyed because, from a niggardly view of biodiversity, they are diluting the genetic purity of the original. It is as if individual trees with character and rich biographies can continue to have an existence only through the pickling (by cloning, for example) of their unique genetic identity; and that being carried forward by the eddying, unpredictable streams of reproduction, as all other organic life is, would obliterate their authentic essence. As a principle guiding our treatment of nature as a whole this, it hardly needs saying, would have stopped life on earth in its tracks. We too often forget that trees have been successfully negotiating all the processes to which we subject them – mutation, evolving adaptations to changed circumstances, cross-breeding, self-planting, regenerating – entirely of their own accord for millions of years.

There’s an appealing young Wood’s cycad in the Hortus Botanicus in Amsterdam. It grows, unprotected, in a small wooden tub of the sort you might use for a favourite rose by the front door. Its next-door neighbour in the small conservatory is a tiny olive tree which has been potted in an old olive oil can, a pairing whose subliminal message is that all plants are equally valuable, regardless of their human usefulness and entanglements. I like the unpretentiousness of this modest offshoot of 200 million years of history. But I’ve experienced the mana that can attach to Big Trees – the Old Ones, the survivors against the odds, the lasts of their kind. They can reverse history’s telescope, and in their singularity sometimes be portals into deep time, through which you can glimpse evolution rolling backwards: the solitary tree becoming the grove, then the teeming forest, then the community of aboriginal species. You can look forward from them too, perhaps to the moment when they cease to be and all that is left, in Oliver Sacks’s words, is ‘the sad, compressed memory in the coal’.

Sacks – a man equally visionary as both botanist and neurologist – became obsessed with ancient species as a child, when he was taken to see dioramas of the Jurassic Age in the Natural History Museum and to the cycad beds in Kew’s great Palm House. He was transfixed by their overwhelming sense of antiquity and strangeness, and had dreams of them as ‘an Eden of the remote past, a magical “once” … They neither evolved nor changed, nothing ever happened in them; they were encapsulated in amber.’ Later, as an adult, he understood that their peculiarity magnified his understanding of the essential dynamics of life. He saw the cycads as both ‘tragic and heroic’. The coal-forest plants they were most closely related to have long vanished from the earth, and the cycads find themselves ‘rare, odd, singular, anomalous, in a world of little, noisy, fast-moving animals and fast-growing, brightly coloured flowers, out of sync with their own dignified and monumental timescale’.

In the 1990s Sacks visited a string of islands in the Pacific where a strange endemic colour blindness exists that might possibly be related to regular consumption of flour made from cycad seeds. He tells of one evening on Rota, a small island east of Guam, when he sits on the beach, amongst cycad trees that come down almost to the water’s edge. The sand is littered with their giant seeds, and fiddler crabs are emerging to scissor their way in for the kernels. A light wind has got up, and the strengthening waves are catching some of the seeds and drawing them into the sea. Most are washed back onto the shore, but Sacks watches one surfing the waves, beginning to edge away and perhaps on the beginning of a journey across the Pacific. There is a chance that it will pitch up on another island and germinate; and a more remote but thrilling possibility that it might eventually hybridise with another cycad species there, and extend the family’s survival opportunities into the future. If a human hand helps in the fertilisation, it would seem to me no different from the lucky intervention of an enterprising weevil, simply speeding up a process that could have happened entirely naturally. Similarly, in the journey between hunter-gathering and domestication it is often difficult to tell whether it is plants or people that are driving the developments.