The Vegetable Lamb: Cotton

IN THE MIDDLE AGES it was not thought in the least improbable that plants were capable of changing into other beings – maybe not humans, as in classical mythology, but certainly into other kinds of organic growth. How else could new forms emerge, or be explained? In the latter half of the fourteenth century a story began appearing in western Europe about a creature from Tartary (then comprising most of central and north-eastern Asia) which was half plant, half animal. A chimera, like the Green Man. In the notorious Travels of Sir John Mandeville (circa 1357), a book which was almost certainly written not by the St Albans-born knight, but by a Flemish monk who himself may have been no more than a collector and plagiarist of others’ adventurous tales, the more fantastical and fanciful the better. (It was typical of the book, and the times, that Mandeville admitted he hadn’t actually been to the Garden of Eden himself but was certain it still existed.) Whatever its origins, the Travels included an account of this fabulous organism, which Mandeville claimed to have seen in ‘the Lond of Cathaye, towards the high Ynde’:

There growth there a maner of Fruyt, as though it weren Gowdres: and when thei ben rype men kutten hem ato, and men fynden with inne a lytylle Best, in Flesche, in Bon and Blode, as though it were a little Lomb, with outen Wolle. And Men eten both the Frut and the Best; and that is a great Marveylle. Of that Frute I have eaten; alle thoughe it were wondirfulle, but that I knowe well, that God is marvellous in his Werkes.

It sounded like a parody of an Old Testament parable: the Lamb of God as an edible vegetable.

More than two centuries later, the usually more reliable French botanist Claude Duret devoted a whole chapter of his Histoire Admirable des Plantes (1605) to ‘The Boramets of Scythia, or Tartary, true Zoophytes or plant-animals; that is to say, plants living and sensitive like animals.’ He made no claim to have seen the vegetable lamb, but confirmed Mandeville’s story, and filled in more details from a fifth-century Hebrew text, part of the collection that contained the first written accounts of the Genesis creation myths. In Hebrew the creature was called adnei hasadeh (literally, ‘lord of the field’). It was shaped like a lamb, and had a stem growing from its navel which was rooted in the ground. According to the length of this trunk or stem, the lamb was able to devour ‘all the herbage which it was able to reach within the circle of its tether’. Then it expired.

Explorers and writers began discovering – and elaborating – more details of the creature’s extraordinary existence. It had four limbs and cloven hooves. Its skin was soft and covered with wool. It had no real horns, but the long hairs of its head were intertwined like vertical pigtails. The wolf was the only predator of the Borametz (a Tartar word signifying lamb), but humans seemed well acquainted with its gourmet qualities, which, in keeping with its chimerical nature, crossed biological divides. Its blood was as sweet as honey. Its flesh tasted of crab, or possibly crayfish. Baron von Herbenstein, German ambassador to Russia, passed on (the accounts are invariably second or third hand) what he regarded as a story that vindicated the Borametz’s woolliness. ‘I was told by Guillaume Postel, a man of much learning, that a person named Michel’ had assured him that he had seen near Samarkand ‘the very soft and delicate wool of a certain plant used by the Mussulmans as padding for the small caps which they wear on their heads, and also as a protection for their chests’. By the end of the sixteenth century the story had entered Christian iconography. The French writer Guillaume de Saluste, in his 1578 poem La Semaine, imagines the plant as one of those creatures that excited the attention of Adam as he wandered through the Garden naming things. He makes a kind of riddle out of its paradoxical properties.

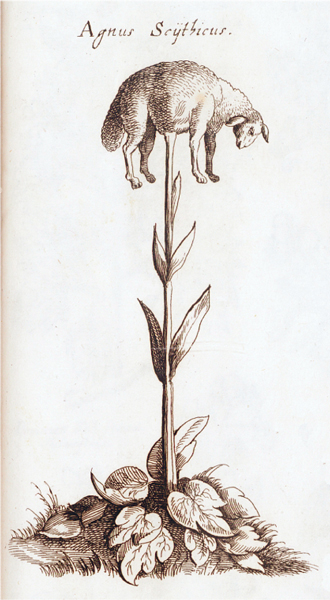

A seventeenth-century illustration of the vegetable lamb, by Matthäu’s Merian the Younger. A confused picture of a confusing myth, as this lamb could not reach the pasture beneath.

The nimble plant can turn it to and fro,

The numbed beast can neither stir nor go,

The plant is leafless, branchless, void of fruit,

The beast is lustless, sexless, fireless, mute:

The plant with plants his hungry paunch doth feed,

Th’admired beast is sown a slender seed.

In Britain, the flyleaf of the early editions of John Parkinson’s great seventeenth-century horticultural manual, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (the title is a clever bilingual pun: it means Park-in-sun’s park on earth), is adorned with an illustration of ‘Adam and Eve admiring the plants in the Garden of Eden’. There, amongst a luxuriant collection of apples, palms, lilies, cyclamens, tulips and a ravishing long-haired Eve, is an unmistakable vegetable lamb on its stalk, still with a lot to eat.

With the dawning of the Enlightenment, more sceptical eyes were turned on this extravagant legend. A few shrivelled relics, reputedly onetime Borametz, turned up in European museums, but none of their donors seemed to have set eyes on the living source. It was invariably a story passed on by a colleague who’d read it in some armchair explorer’s memoirs. The suspicion grew that it was an ordinary but previously undescribed plant or artefact, badly reported, and hyped up by secondhand rumours and Tartarian whispers. The first scientist to challenge the myth was Dr Engelbrecht Kaempfer, a surgeon for the Dutch East India Company in the late seventeenth century. His searches for the ‘zoophyte feeding on grass’ were fruitless, but he discovered a breed of sheep local to the area round the Caspian Sea which had exceptionally soft skin and fine wool. There was a local tradition of killing pregnant ewes to harvest the even finer fleeces of the embryonic lambs. Their skin was as thin as vellum. It shrunk on drying, and ‘assume[d] a form which might lead the ignorant and credulous to believe that it was a woolly gourd’. Kaempfer believed that it was these desiccated skins which had found their way into European collections to be presented as examples of the zoophyte’s fleece.

A more plausible explanation appeared when the arch collector Sir Hans Sloane exhibited another withered object to the assembled Fellows of the Royal Society in 1698. For the next two centuries this artefact was regarded as the source of the entire vegetable lamb mythology. It was part of the root (rhizome) of a tree fern from China, about a foot long and as thick as a man’s wrist, and had been crudely whittled, so that it appeared to have a sheep-like head and four legs cut from the stalks. It was covered with yellowish down, a quarter of an inch thick in places. A fabulous plant made out of a fabricated plant. During the eighteenth century, more specimens of these carved rootstocks were seen in Asia, all belonging to the tree-fern genus Dicksonia. They were made as toys and curiosities, and doubtless passed off to gullible tourists as something more mysteriously oriental.

And there the matter rested to everyone’s satisfaction for another hundred years – bewilderingly, since it stretched credulity that a crude gewgaw could be the source of an elaborate and widespread fable more than 1,000 years old. But in the 1880s, Henry Lee, Fellow of the Linnaean Society and myth-busting author of Sea Monsters Unmasked and The Octopus, or the Devil-fish of Fiction and Fact, believed he had found the true solution, and one which had a particular resonance with Britain’s current imperial ambitions. He poured derision on the ferny figurines. ‘I have to express my very decided opinion that they and the “lambs” (?) made from them had no more to do with the origins of the fable of the “Barometz” [sic] than the artificial mermaids so cleverly made by the Japanese had to do with the origins of the belief in fish-tailed human beings and divinities.’ Writing from the redoubts of the Savage Club in London, a bolthole for travellers and intellectual eccentrics, he offered a radically different interpretation, still rooted in the concept of mistaken identity but more plausible than any previous attempt. Reviewing all available evidence, he concluded that we should now be able to recognise with confidence the vegetable lamb’s true ‘forms and features under the various disguises it was made to assume by the wonder-mongers of the Middle Ages’, and appreciate that it was ‘a plant of far higher importance to mankind than the paltry toy animals made by the Chinese from the root of a fern’. The original Borametz, he declared triumphantly, was none other than the pod-bearing cotton plant. It was a satisfying and patriotic verdict from a man who, in his closing chapter, makes an impassioned plea for Britain’s retention of India and of the huge wealth represented by its cotton plantations.

What is odd is that this Byzantine myth should have taken root in Europe at all. Cotton was a familiar plant. It had been imported by southern Europe since classical times, and was a common commodity across the whole continent by the fourteenth century. By the late 1500s fabrics were being made in Britain from raw cotton by Flemish spinners and weavers. The herbalist John Gerard, writing in 1597, was nonchalant about the plant: ‘To speake of the commodities of the wooll of this plant were superfluous, common experience and the dayly use and benefit we receive by it shew them.’ He tried to raise it in his garden in Holborn. It ‘did grow verie frankly, but perished before it came to perfection, by reason of the cold frosts that overtooke it in the time of flouring’.

Hardly a mysterious alien, then, either as raw pod or as finished fabric. Even if the parent plant was unfamiliar, it’s implausible that anyone seeing it for the first time – an unassuming bush bearing seeds enclosed in fig-sized bolls of fluff – could mistake it for some phantasmagorical plant–animal hybrid. But the origins of the fable, or perhaps the psychology behind it, resonate with the true history of the cotton plant, which is almost as extravagant as the fictional myth of the vegetable lamb.

There are four members of Gossypium genus (part of the mallow family) which are known as cottons, two in the Old World and two in the New. They have been cultivated and hybridised for so long that, in the case of the Old World species, G. arboreum and G. herbaceum, no truly convincingly wild ancestor has ever been found. The cultivars may have originated in Africa even before the Stone Age, from one of the wild Gossypium species still found there, and their wool used in ways unrelated to cloth making, perhaps as a ceremonial adornment, or a staunch for wounds. At some stage these early cultivars were taken to Asia, and evidence of the first expert weaving is from about 1000 BC, in the Indus Valley. They spread slowly west, and in the Book of Esther, King Solomon’s palace walls are described as being covered with cotton fabric. In the fifth century Herodotus, one of the more reliable classical commentators, reported, ‘The Indians have a wild-growing tree which instead of fruit produces a species of wool similar to that of sheep, but of finer and better quality.’ You can see the germs of a vegetable-lamb myth in his description, but no sense that Herodotus thought cotton anything other than an ordinary plant with unusual accoutrements. Five hundred years later Pliny the Elder finds it has migrated further west, and recognises the pods as, botanically speaking, a seed-containing fruit: ‘The upper part of Egypt, facing Arabia, produces a shrub which is called gossipion … The fruit of this shrub resembles a bearded nut, which contains a soft wad of fine fibres which can be spun like wool and which is unsurpassed by any other substance in respect of whiteness and delicacy.’ Cotton continued to follow a familiar track west, through Roman imports of fabric from India to the introduction of plants and cultivation techniques by the Moors to Spain and Sicily, around the start of the tenth century.

Then the story takes an unusual twist. The early Spanish colonisers of the Americas took cotton with them, only to find that the indigenous people were already making sophisticated garments from it. When Hernando Cortés arrived in Mexico in 1519, he was presented with a gold-encrusted ceremonial cotton robe by the Yucatan Indians, just before his soldiers set about slaughtering them. Recent archaeological evidence suggests that two different New World species had been in use there for thousands of years. Seeds of G. barbadense discovered in excavations in Chile and Peru, and the remains of yarns and fishing nets made from its silky seed plumes, have been dated back to 4000–3000 BC, and G. hirsutum seeds found in Mexico to 3500 BC. It looks as if cotton had been a cultivated crop in Central and South America for at least 2,000 years longer than in Asia. Then, as genetic science advanced in the 1960s, a bewildering discovery was made. The American cultivated cottons had originated in some ancient cross between the cultivars of the Old World and the wild species of the New. How could this have happened, long before European settlers took their species across the Atlantic?

This is where fact starts to wander into speculation, or what might be called scientific fabulation. One group of botanists have theorised that the seeds of Asiatic cottons found their way across the Pacific millions of years ago, carried by birds or ocean currents. They hybridised with the New World species and then became extinct themselves, leaving their vigorous mongrel offspring to continue the line. Another group, the ‘diffusionists’, argue that cultivated Old World cottons were brought across the sea by the peoples from South East Asia who first colonised the western coasts of the Americas. Yet another group, the ‘inventionists’, maintain stoutly that hypothetical foreign introduction is improbable and that native American cotton species simply underwent a spontaneous chromosomal mutation. This botanical debate reflects the ongoing and fiercely partisan argument about the origins of Native Americans. When did they arrive, and how? Across land from the northern tundra, or by boat from the southern Pacific? The American botanist and expert on the history of economic plants Edgar Anderson once remarked that European ethnographers are more likely to favour the transoceanic diffusion theory, and their American counterparts to patriotically ‘explain our indigenous high culture as a flowering of the aboriginal American intellect. A generation ago, when leading American writers were more uniformly anti-diffusionist than at present, a witty English anthropologist referred to this theory as “the Monroe Doctrine of American Anthropology”.’

None of these modern discoveries cast much light on the substance of the vegetable-lamb myth, originating as it did thousands of years earlier. But they may say something about its origins and enduring shape. It’s clear that story making is compulsive in all societies and at all times, and that the idea of hybridisation, be it between cultures or organisms, is seductively ambivalent. Cotton is an eccentric plant, tailor made to be a provocative subject on both counts. (The fibrous fluff that embeds the seeds has ethereal qualities of its own, as a kind of vegetable mist. In the heyday of spiritualism in the late nineteenth century softly lit plumes and clouds of cotton wool were routine stage props at séances, intended to dupe the faithful into believing they had glimpsed ectoplasm or spirit ‘auras’.)

Myths and fables don’t spring into full narratives directly from the collective unconscious, despite mystical beliefs to the contrary. Even if Claude Lévi-Strauss is right when he suggests that a propensity for myth making is hard-wired into the modern human brain, just as the basic structure of language seems to be, at some point myths have to be articulated, turned into stories by individuals with a gift for narrative. Cotton would have provided promising material for fable spinners as far back as the Neolithic. Ordinary village storytellers also doubtless wove tales around its curious anatomy, to serve as parables or entertainment or for simply making mischief with strangers. The stories would have been progressively ornamented as they passed from teller to listener, yet always maintaining two essential parable-shaped motifs – the idea of the plant–animal chimera, and its collapse when its limited food was grazed out. It would have been various versions of these tales, not some mass delusion, which early European travellers picked up. And their long survival suggests that the myth’s core struck some sympathetic echo in the societies in which it was first told as well as in the wider world.

Jim Crace’s historically telepathic novel about the final days of the Neolithic era, The Gift of Stones, has as its central character a storyteller who cannot contribute to his small community’s trade of knapping and finishing flints because he has lost an arm. So he becomes a professional spinner of yarns, a polisher of tales. He enchants his fellow villagers with outrageous stories, mostly based on romantic and fantastical riffs on their humdrum, stony lives. He explains what makes for a good story, which if successful enough will take root as a fable. ‘Why tell the truth when lies are more amusing, when lies can make the listener shake her head and laugh – and cough – and roll her eyes? People are like stones. You strike them right, they open up like shells.’

But enduring myths are not exactly lies. The ex-Bishop of Edinburgh Richard Holloway suggests that ‘the question we should ask of a myth is not whether it is true or false, whether it did or did not happen; but whether it is living or dead, whether it still carries existential meaning for us in our time’. Chimeras figure so prominently in mythologies that they may carry universal meanings, be the kind of ‘striking’ stories that ‘open [us] up like shells’. Hybrid creatures like the centaur, phoenix, griffin and sphinx occur in myths throughout the world. Often they seem to have some kind of real-world analogue. The double helix of DNA was prefigured in an image on a Levantine libation vase from 2000 BC. It shows two great snakes, also entwined in a double helix, and symbolising the original generation of life. The great biological essayist Lewis Thomas describes a Peruvian deity painted on a clay pot from about 300 BC, believed to be a charm for protecting crops. Its hair, too, is made of entwined snakes. Plants of several kinds are growing out of its body and some sort of vegetable from its mouth, Green Man style. Thomas points out that it is an imaginary version of some real animals, species of Pantorhytes weevils recently discovered in the mountains of New Guinea. They live symbiotically with dozens of plants – lichens and mosses especially – growing in the cracks of their inch-long carapaces, miniature forests which contain a whole ecosystem of mites, nematodes and bacteria browsing on the foliage. Thomas has nicknamed them symbiophilus. We are a kind of chimera ourselves, he wrote, ‘shared, rented, occupied’. Hundreds of species of bacteria inhabit our skin and gut (where they’re pleasingly called ‘flora’) and are essential for the efficient working of the digestive and immune systems.

The myths and symbols which echo and maybe intuit the workings of these real-world communities seem to celebrate the tendency for living things to join up, form partnerships, live inside each other for mutual benefit. Human cells are formed from collections of other organisms, living together but independently inside these enclosed bubbles. Our myths of chimera may be born out of the optimism of this idea, or an ancient understanding of it. The story of the vegetable lamb is resonant and densely layered. It’s a parable about natural economy and the inseparability of plants and animals. In its evolution it toyed with Judaeo-Christian icons and ideas: the Tree, the Fruit, the Lamb; ‘all flesh is as grass’. The vegetable lamb was a beast which, like a plant, had an umbilical connection to the earth. A plant which, like a beast, lived by grazing and died when it had exhausted its food supply.