Life versus Entropy: Newton’s Apple

NEWTON’S BEST-KNOWN FLIRTATION with the vegetal world was to witness a falling apple and be inspired to posit gravity as a fundamental cosmic force consistent with his Second Law of Thermodynamics. Both laws insisted that objects could not spontaneously fly upwards from the earth’s surface. Newton was living at the family farm at Woolsthorpe Manor in Lincolnshire at the time the idea struck him, and practising science as a cottage industry, as it was to be practised by ‘natural philosophers’ for the next two centuries. His study remains much as it must have looked in the 1660s, with one window reduced to the slit he used for directing sunbeams through his prisms, and the perennially sensible presence of a bed. Outside there are still remnants of the working farm, and of the tree that deposited the historic apple. It doesn’t have its original trunk, but it is still the same organism, sprouted anew from the withered stump in a defiant challenge to entropy. Its fruits are big and heavy, and would certainly have made an impression had one fallen on Newton’s head, as in the legend.

What actually happened is related by the antiquarian William Stukeley, who had dinner with Newton in 1726, not long before his death, and listened to his recollections of an autumn day at Woolsthorpe:

After dinner, the weather being warm, we went into the garden and drank there, under the shade of some apple trees … he told me he was just in the same situation, as when formerly [probably in 1666], the notion of gravitation came into his mind. It was occasioned by the fall of an apple, as he sat in contemplative mood. Why should the apple always descend perpendicularly to the ground, thought he to himself …

To an eighteenth-century botanist, an equally perplexing question was how an apple could, as it were, be raised perpendicularly from the ground, how biological growth could defy gravity. What was the vital force that made life able to challenge the Second Law’s vision of an ever descending spiral of energy? The peculiarity of Newton’s apple – it’s now recognised as a scarce variety called Beauty of Kent – added a kind of lateral assault on the Law, contradicting the gravitas of Linnaean certainties and the idea of ‘species fixity’. By the eighteenth century there were tens of thousands of apple varieties in existence, all the Old World varieties at least now known to have descended from a single species in central Asia in a glorious pan-continental proliferation. The generation of biological forms (what we call biodiversity today) and the tendency of all living systems to become progressively more diverse and complex fly against the cosmic gloom of the Second Law. The polymathic biologist and essayist Lewis Thomas put the energy equation represented by biology’s intervention into the inanimate world quite simply. ‘[T]he information of the biosphere,’ he wrote, ‘arriving as elementary units in the stream of solar photons … [is] rearranged against randomness.’ Life – at least until the stars burn out – trumps entropy.

That the domestic apple originated from a wild apple species in Tien Shan in north-western China had been suspected by the pioneering Russian plant geographer Nikolai Vavilov back in the 1920s. For a long while it had been assumed in botanical and horticultural circles that the domestic fruit had the European crab apple, Malus sylvestris, somewhere in its pedigree, either as a direct ancestor or a contributor to the lineage. Exhaustive studies on the DNA of domestic varieties have proved this assumption to be wrong. All domestic varieties are basically the same species, Malus pumila. Controlled attempts to cross crab apples with other Malus species and varieties have all been literally fruitless.

At the start of the twenty-first century the distinguished Oxford botanist Barrie Juniper, working both in the laboratory and in the field in Tien Shan, pieced together for the first time a full and plausible outline of the evolution of the domestic apple. It is a complex story, involving turbulent geography, genetic effusiveness, improbable mammalian fruit gourmets and prehistoric orcharding experiments.

The topography of Tien Shan was a crucial factor. For much of its history it was subject to violent earth movements, bringing ancient rocks of every geological type to the surface, creating new canyons and cliffs and caves, exposing fresh soil and breaking up existing vegetation cover. As a result the region became both very fertile and full of botanical refuges, cut off from neighbouring areas. It developed ‘fruit forests’ in which the precursors of many important species grew: apricot, almond, plum, pear, quince. At some point possibly 10 million years ago, the fruits of an unknown form of apple – maybe one related to the Siberian crab, Malus baccata – were carried by birds into this ecological labyrinth. Different populations were isolated in different valleys, and would have evolved through spontaneous mutation, and selection pressure from soil and habitat variation. Occasionally these populations would have come together and interbred, and the region would have begun to support an ur-apple species close to today’s Malus pumila, intrinsically and epigenetically varied in size, shape, colour, sweetness and time of fruiting. The main drivers of selection, the pre-human apple breeders, were probably bears, which were common in the region thanks to the abundance of caves as secure refuges, and the similar abundance of fruit. Bears browse on windfalls and climb trees for the choicest fruit.

Chinese brown bears would have selected the sweetest and largest apples, scattering and manuring their pips with their faeces. Apples don’t come true from seed (that is the corollary of the immense variation in the fruits) but the bears’ choices would have shifted the gene pool in the direction of greater size and palatability. They were the midwives of the modern apple. Wild horses were another important vector. They also like apples and would have added their own well-dunged contributions to the seed bank.

Some 7,000 years ago nomadic human tribes began settling seasonally in the fruit forests, and added their own selection to that already achieved by wild animals. Maybe favourite trees were manured, and the virtues of pruning discovered when trees were broken or lopped for firewood. As tribes migrated west along the Turkic Corridor they would have taken fruit with them, and wilding apples would have followed, springing in unpredictable diversity from discarded cores and the dung of pack horses. Roughly 4,000 years ago apple grafting was discovered, inspired perhaps by the glimpse of a natural pleach between two chafing branches. From this point it became possible to perpetuate favoured varieties by surgically implanting a slip onto another apple stock. It’s not at all impossible that an apple with some of the characteristics of Newton’s Beauty of Kent had already appeared, and been enjoyed enough to be passed on. From this moment the voyage of the apple joins and resembles that of other cultivated crops.

Throughout the Middle Ages apple varieties were brought to Britain from the continent, or spotted as rogue seedlings in existing orchards. John Parkinson made a euphonious list in his Paradisus of 1629, including:

The Gruntlin is somewhat a long apple, smaller at the crowne than at the stalke, and is a reasonable good apple.

The gray Costard is a good great apple, somewhat whitish on the outside, and abideth the winter.

The Belle boon of two sorts winter and summer, both of them good apples, and a fair fruit to look on, being yellow and of a mean bignesse.

The Cowsnout is no very good fruit.

The Cats head apple tooke the name of the likenesse, and is a reasonable good apple and great.

There is no mention yet of the Beauty of Kent, though there is a Flower of Kent, ‘a faire yellowish greene apple both good and great’. Nor is it listed, a hundred years later, in Philip Miller’s Gardener’s Dictionary (1732), though his catalogue confirms the continuing expression of Malus pumila’s genetic inventiveness in every dimension from scent to fruiting season. (It includes the aniseed-scented ‘La Fenouillet’, and ‘Le Courpendu … or the Hanging Body’ also known then as the ‘Wise Apple’ because it flowers late and escapes spring frosts.)

The global partnership between fruit growers and fruit continued into the nineteenth century. In the United States (where American wild apple species were brought into the breeding line) Henry Thoreau added a Romantic gloss to the roll call by describing mood-and-moment varieties: ‘the Truants’ Apple (Malus cessatoris), which no boy will ever go by without knocking off some … our Particular Apple not to be found in any catalogue, Malus pedestrium-solatium …’ In Normandy in France, a group of highly local cider apples were developed. And in 1841 Thomas Squire, who lived in the town where I grew up, Berkhamsted in Hertfordshire, was planting out a curious Malus seedling just as Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were making regal progress past his garden towards the Kings Arms, my own boyhood local. He named it ‘Victoria and Albert’, later to become ‘Lane’s Prince Albert’ after the nurseryman, John Lane, who successfully commercialised it. But the tree survived in Mr Squire’s garden until 1958, and the fruit still holds a Thoreauvian aura for me – ‘The Apple of carefree youth, the Sunday lunchtime apple …’

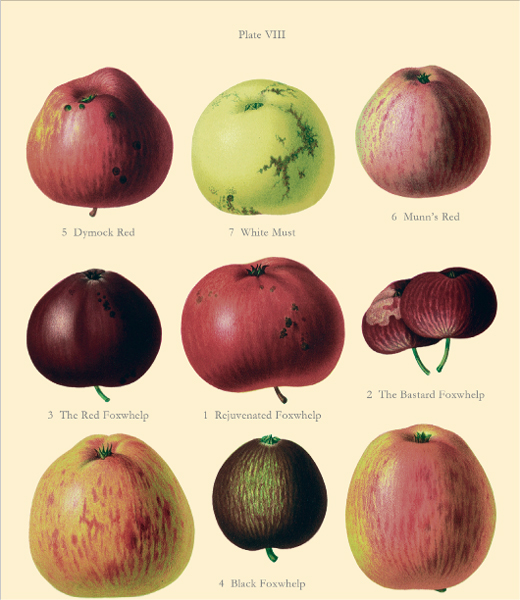

The second half of the nineteenth century probably marked the zenith of apple diversity. Twenty thousand varieties are believed to have existed worldwide, with 6,000 in Britain alone. The Welsh–English borderlands had one of the densest concentrations of apple orchards, but they were beginning to be abandoned because of the prolonged agricultural depression. This was the home country of the enterprising Woolhope Naturalists’ Field Club, based in Hereford and commanded by the tireless Dr Henry Graves Bull. Dr Bull was the originator of the Fungus Foray, an annual four-day event in which members of the society toured the countryside in coaches, inspecting and gathering fungi which were later served up to them at a grand dinner in the George and Dragon public house in Hereford. The forays took in the local orchards, and members were able to see at first hand the decrepit state many had fallen into. In the early 1870s Dr Bull suggested that the club take up the subject of ‘the Pomology of the county’, and investigate with some urgency the history and surviving variety of its apples and pears. The Royal Horticultural Society’s head of gardens, Dr Hogg, was enlisted as technical advisor, and a series of exhibitions was held in Hereford, to which members and local fruit growers sent samples for naming. Many couldn’t be named ‘for they had no names … [but] were valuable apples, so quite distinct in character, and with such excellent qualities that they deserved to be better known’. Dr Hogg suggested that a local ‘Pomona’ (an illustrated catalogue of apples) should be compiled, and offered to edit it himself.

The first part, in quarto format and with watercolour illustrations, appeared in 1878. Herefordshire proved to be a hot spot of pomological diversity. Twenty-two species were included in the first tranche, rising to forty-one in the second, published in 1879. The project proliferated much like Malus itself, infiltrating new regions, absorbing local skills, developing a special vocabulary of fruit description. In 1880, in response to widespread acclaim for the first three parts, the club decided to make the Pomona a national project. The autumn exhibitions became more lavish and imported specimens from other shows. That October there were more than 2,000 dishes of fruit on display. In 1884 club members crossed the Channel to visit, and exhibit at, an apple show in Rouen in Normandy, the organisers of which proved to be compiling their own cider apple directory. This provided more revelations about the radiation of apple variety: what, in Herefordshire, had been called ‘Norman’ cider apples proved to be quite unlike any grown in Normandy. Specimens of the true Norman apples were accordingly taken back to England where, ‘in some haste’, paintings and descriptions of them were made and added to the Pomona.

The work eventually ran to seven parts, which were bound into two volumes and published as The Herefordshire Pomona in 1885. It included 432 varieties of apple and pear, and amongst them, at last, is the Beauty of Kent. Roger Deakin once described the story of the apple’s evolution as ‘as something between the Book of Genesis and the Just So Stories’, and the Beauty of Kent is a late arrival on the stem of Malus, its unknown forebears having travelled thousands of miles before it begat the fruit which fell in front of Newton in Lincolnshire, and which had no recognised name for another century and a half. The Pomona records its first mention in a nurseryman’s catalogue from about 1820, and illustrates it with a simple black-and-white cross section. But the description is lusciously and attentively sensuous, and you can glimpse the human fruitarian carrying on the work of those discriminating Chinese bears:

Fruit, large, roundish, broad and flattened at the base, and narrowing towards the apex, where it is terminated by several prominent angles. Skin, deep yellow, slightly tinged with green, and marked with faint patches of red on the shaded side, but entirely covered with deep red, except where there are a few patches of deep yellow on the side next the sun. Eye, small and closed, with short segments, and set in a narrow and angular basin. Stalk, short, inserted, in a wider and deep cavity, which, with the base, is entirely covered with brown russet. Flesh, yellowish, tender, and juicy, with a pleasant subacid flavour.

Apple evolution continues. If the direction of modern mass cultivation and selling is entropic, favouring an ever-shrinking range of varieties and increasing uniformity of fruit, the apples themselves have different ideas. Cores left over from country picnics and thrown out of cars (and trains: Thoreau listed ‘the Railroad Apple’ in his Romantic lexicon) can sprout into wildings whose unpredictable fruit echoes the diversity of the fruit forests. One summer in the 1970s I was wandering along the beach at Aldeburgh in Suffolk when I chanced on a dwarf apple bush nestling between two shingle ridges. It came up no higher than my chest, and sprawled across maybe six yards of the beach. Goodness knows how much of it lay under the shingle. It had the beginnings of a few fruits, but I have never seen it at the right time to pick any. I discovered later that it’s a well-known local curiosity, and the locals scrump the apples as soon as they have any semblance of ripeness. No one knows how it arrived in this improbable position. It may have sprung from a thrown-out core or bird-sown pip that shingle movements buried serendipitously near an underground drift of soil or freshwater spring. Another theory is that it is the last relic of an eighteenth-century orchard, attached to a derelict cottage a hundred yards inland, which was buried as the coastline moved inexorably over it. This last tree stuck it out, not drowning but waving. Its topknot grows close to the stones, as densely twigged as a thorn bush.

However it originated, its endurance is remarkable. Pruned and pinched by the cold east winds, indifferent to dousings by salt spray at the highest tides, it must be one of the hardiest apple trees in Europe. I hope some enterprising fruitarian, mindful of the ever-rising sea levels, has taken grafts.