‘Vegetable jewellery’: The Fern Craze

THE FIRST INHABITANTS of domestic Wardian cases, though, were home grown, and more subtle in their appeal. The eruption of interest in fern collecting – which eventually became a ‘pteridomania’ (from Pteridus, the Latin name for bracken) that swept as far as Australia – is one of the more intriguing puzzles of nineteenth-century plant culture. The Victorian mindset – a case study in the tension between contradictions – was enthralled by the sensational and the exotic, sometimes to the point of prurience. But this predilection was balanced, almost penitentially, by a taste for the delicate and the faery, the world of shadow. (David Elliston Allen astutely notes that ‘the fern craze opened as men’s clothes, quite suddenly, turned black’.) Ferns’ intricate, fractal forms – the ‘extraordinary exactitude of their ramifications’ as one author put it – made them ideal subjects for the contemporary taste for the Gothic. The popular natural history writer Edward Newman made the link explicit: ‘The Gothic windows of an old abbey afford many convenient crevices for a pretty fern.’ Thomas Hardy, in his descriptions of heathland in The Return of the Native, brought a working architect’s eye to his description of ferns’ intrinsic patterning: ‘The ferny vegetation around … though so abundant, was quite uniform: it was a grove of machine-made foliage, a world of green triangles with saw edges, and not a single flower.’ They also helped solve a perennial problem for middle-class Victorian men: what do with their womenfolk, an active new generation with time on their hands and open to dangerous temptation. Sending them hunting for ferns – pliant, demure, not obviously sexual creatures which lived in cool, cosseted nooks – seemed a perfect solution. The pastime was ‘particularly suited to ladies; there is no cruelty in the pursuit, the subjects are so brightly clean, so ornamental to the boudoir’. It was this audience that the florid garden journalist Shirley Hibberd had in mind for his best-selling book The Fern Garden (1869). He enthused about ‘vegetable jewellery’ and the ‘plumy green pets glistening with health and beadings of warm dew’ in their glass cells.

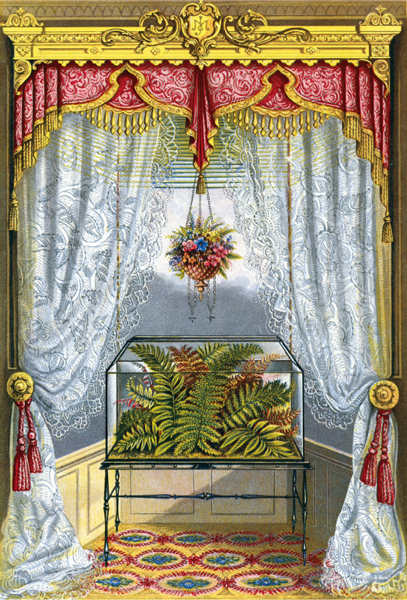

A Wardian case, full of ferns, suspended in a bay window. From Cassell’s Home Guide, late nineteenth century.

But Wardian cases were expensive, ranging from thirty shillings to two pounds, and initially the fern cult was largely confined to wealthy garden enthusiasts and botanists who felt able to manage with a bell jar (a jar big enough to cover seven or eight plants cost a couple of shillings). Pteridomania didn’t become a full-blown craze until the 1850s. The repeal of the iniquitous glass tax in 1845 was an essential prelude, greatly reducing the cost of all glass containers as well as windows. The pivotal year was 1851. Ward’s original bottle, with the plants still inside and celebrating twenty-one years without watering, was put on show at the Great Exhibition in London. The same year saw the publication of what proved to be the breakthrough popular handbook, Thomas Moore’s A Popular History of the British Ferns. This was illustrated in colour by W. H. Fitch, one of Britain’s foremost botanical artists, and contained a list of places where the choicest and less common species were to be found. Moore’s book put into popular currency a trend that had already become evident amongst more scientifically inclined fern lovers: a taste for rare, unusual and frankly peculiar forms. Ferns, as a tribe, seem especially prone to throw up odd forms and ‘sports’, the fifty or so wild British species being further divided into hundreds of varieties whose fronds are forked, crisped, crested or in some other way marginally aberrant. M. C. Cooke’s A Fern Book for Everybody (1867; the back cover carries an advertisement for Dick Radclyffe’s ‘Window Garden Requisites’ shop in High Holborn) lists some eighty-five forms of hart’s tongue, a common and attractive species whose tufts of glossy, bright green blades grow on rocks, walls, damp hedge banks, and even as epiphytes on mossy branches. It’s named from its shape, like a protruding tongue. Local names aren’t fussy about which animal it belongs to: it’s also sheep’s, fox’s, horse’s tongue – though the varieties would suggest some alarming glossal pathologies. They include var. cristatum, in which the frond divides near the top, with ‘each division again and again subdivided so as to form a bushy tuft’; a ‘proliferous variety (viviparum) [which] bears on the surface of the fronds numerous little miniature plants, which continue adhering to the skeleton as the frond decays’; laceratum, described as ‘endive-leaved’; and rugosum, ‘a strange-looking stunted form, with short ragged-edged fronds’. Cooke’s guide, written twenty years after the craze reached its height, also sounds a warning about the impact of collecting. The Tunbridge filmy fern, a fragile species with ethereally thin fronds, had been one of the first species to be housed in Ward’s cases. Forty years on, the ‘rapacity of fern collectors,’ in Cooke’s words, ‘has left very little of this interesting fern to flourish at Tunbridge Wells, on the old station from whence its name is derived’.

Professional fern traders were the real problem. In a manner reminiscent of orchid hunters in the tropics they cleared whole areas, digging up ferns indiscriminately and leaving it to the market to sort out what was interesting. The largest and most elegant native species, the Royal fern, Osmunda regalis, was all but eliminated from the Isle of Man. The same thing happened in Cornwall, where one fern seller boasted of having despatched to London a truckload of roots weighing five tons. There were reports of ferns being poached from private estates in Devon and sent up by hamper to Covent Garden. But the amateurs weren’t blameless. The ‘proper tools’ they recommended were semi-industrial: a steel pick, spades and trowels, some lengths of cord and a stout canvas bag. Shirley Hibberd, in another influential book (Rustic Adornments for Homes of Taste, 1856), confessed to using a large carpet bag ‘fitted with tin boxes, into which the Ferns were laid along with as much of their natural soil as possible’ – a rather confined cage for organisms he went on to describe as ‘shy wood-sprites’.

A fern-decked dress designed by Nicholas Chevalier for Lady Barkly, wife of the Governor of Victoria, 1860. (Pteridomania was as fashionable in Australia as in Britain at this time.)

The collectors’ preferred trophies made for an ambivalent posy. Mostly they were aberrations, mutations, evolutionary dead ends resulting from chromosomal turbulence; and Hibberd’s description of ferns as ‘plumy … pets’ usefully links them with the freakish, inbred animals beloved in some quarters of the pedigree dog and cat world. Even the most botanically minded pteridomaniac showed no interest in how they had come to be, and what, if anything, they might contribute to the biological future of the fern tribe (the craze peaked just before Darwin’s Origin of Species). And in the end, like all fashions with no intellectual base or driving force, it became as hypertrophied as a proliferous hart’s tongue (‘continuing to adhere to the skeleton as the frond decays’) and bored itself to death with its own excesses. The most desirable varieties became scarcer and more bizarre. As the originals declined in the wild (some rarer species became extinct in a few locations) virtual ferns sprouted everywhere – in the design of furniture, wallpaper, needlework, and as shadowy facsimiles made by rendering their images on oiled paper with the soot from a candle flame. The glass ferneries themselves became rococo fantasies, made to resemble Turkish mosques and European cathedrals. The ‘Tintern Abbey Case’ was a favourite, with fern-stacked sides and a back panel carrying a facsimile stone wall and stained-glass window, draped with real ivy.

The fern cult says much about Victorian society, its acquisitiveness and readiness to use plants as mirrors of mood and status. In the end the ferns were no more than cultural goods; and if they were an early example of natural capital, they went through the full economic cycle of boom and bust.