‘The Queen of Lilies’: Victoria amazonica

IT WAS A MEASURE of Britain’s dominance of European botany in the mid nineteenth century that its scientific establishment was able to blank out four separate ‘discoveries’ by French and German explorers of the plant that became the sensation of the Victorian era, and claim it as a regally blessed national treasure. The Amazonian water lily’s story is muddied with misidentifications, lost specimens, internecine botanical squabbles and political spin. This makes it hard to trace with any certainty in what order the key events occurred, but highlights what crucial nationalistic tokens plants could become in the nineteenth century.

The first European to see the fabled lily seems to have been Thaddaeus Haenke, a Bohemian scientist employed by the Spanish government to search for plants in South America. In 1801, exploring a marshy canal connected to the river Mamoré in Bolivia, he encountered a water lily of prodigious proportions. He made a few sketches, which clearly identify the species, but no written notes. Nothing would have been known about his sighting if, thirty years later, the French botanist Alcide d’Orbigny hadn’t met Haenke’s companion on that canoe trip. Father La Cueva told Orbigny that the spectacle of the lily had caused Haenke to be ‘transported by admiration’, and drop to his knees in praise of the ‘author of so magnificent a creation’.

Another Frenchman, Aimé Bonpland, supervisor of the Empress Josephine’s spectacular gardens at Malmaison, now enters the play. On Josephine’s death, Bonpland decided to move to South America where he’d carried out his early scientific work with the great Alexander von Humboldt. He was exploring rivers near the town of Corrientes in Argentina in 1820, when he saw ‘a magnificent aquatic plant, known to the Spanish as maíz de agua [water corn]. I described it, and placed it in the genus Nymphaea.’ The locals ground its roots as flour and Bonpland’s interest seems to have been partly in the possibilities of commercial cultivation. But he got trapped by a civil war. The seeds he eventually sent to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris never germinated, and in any case he’d seen a different species from Haenke.

D’Orbigny, who’d seen both the Corrientes and the Mamoré water lilies, was the first to realise they were separate species. The former had leaves which were green on both sides. The latter’s were green above and red underneath. D’Orbigny was also the first to put on record the water lily’s much older indigenous name, yrupé, from the Guarani y, water, and rupé, a large platter or lid.

Walter Fitch’s anatomical drawings of Victoria amazonica, from the specimen growing at Syon House, 1851.

A decade later, a young scientist from Leipzig, Eduard Pöppig, became the third European to traverse the entire length of the Amazon, from its source in the Andes to the Atlantic. Sometime in the autumn of 1831 he was exploring one of the river’s igaripés, side channels, when he came upon a large area completely covered with huge water lilies, ‘the most magnificent plant of its tribe,’ he declared. He was reminded of the giant Asian water lily, Euryale ferox, the Gorgon plant, and thought that this new discovery was from the same family. He accordingly dubbed it Euryale amazonica, and preserved parts of the plant in alcohol to take back to Leipzig. He arrived home in October 1832, and a month later published a full description, Latin name included, of the ‘new’ water lily in a German scientific journal. The news did not cross the Channel, and it was a British-sponsored scientist who, five years later, finally propelled the Amazon water lily into stardom. Robert (eventually Sir Robert) Schomburgk was a Silesian, but his South American expeditions were financed by the Royal Geographical Society. He wrote about what he’d seen in a letter to the Royal Botanical Society, but its contents got their first public airing, according to Wilfrid Seawen Blunt, in front of a meeting of the ‘Society of Practical Botanists’ in the Strand in September 1837. It sounds like an archetypal Victorian plant salon, a gathering of artisan enthusiasts and scholarly gentlemen in London’s intellectual heartland whom Schomburgk rose to address:

It was on the 1st of January this year, while contending with the difficulties that nature opposed in different forms to our progress up the River Berbice [in British Guiana], that we arrived at a point where the river expanded and formed a currentless basin. Some object on the southern extremity of this basin attracted my attention. It was impossible to form any idea of what it could be, and animating the crew to increase the rate of their paddling, shortly afterwards we were opposite the object which had raised my curiosity. A vegetable wonder! All calamities were forgotten. I felt as a botanist, and felt myself rewarded. A gigantic leaf, five to six feet in diameter, salver shaped, with a broad rim, lighter green above and vivid crimson below, resting upon water. Quite in character with the wonderful leaf, was the luxuriant flower, consisting of many hundred petals, passing in alternate tints, from pure white to rose and pink. The smooth water was covered with them, and I rowed from one to the other, and observed always something new to admire.

Schomburgk, an ambitious Romantic, wanted to honour the new Queen and suggested the water lily was regal enough to be named Nymphaea victoria. The young Victoria, who had only just taken the throne, asked for Schomburgk’s drawings to be sent to the Palace, and quickly agreed that her name could be attached to the flower. Almost immediately Victoria’s water lily became a symbol of the new monarch and Britain’s latest South American colony.

The war of spin that followed degenerated into botanical French farce, though the bickering was taken very seriously by those involved. John Lindley, one of the country’s most influential botanists, noticed on examining Schomburgk’s dried specimens that the plant was not a Nymphaea at all, and in a clever diplomatic move suggested it was from a whole new genus, which was open for naming after the teenage Queen. So the Mamoré water lily, he pronounced in a paper in February 1838, should now to be called Victoria regia. But another name – Victoria regina – had already been coined by John Edward Gray, President of the Botanical Society of the British Isles, in a paper published five months before. For years the two men squabbled about which name had the prior claim until, in 1847, a German museum curator, Johann Klotzsch, reminded the warring Britons that the plant had already been named in print fifteen years before, as Euryale amazonica. Lindley and Gray, insular men for all their botanical nous, knew nothing of this. The ‘Queen of Lilies’ wasn’t a Euryale (an exclusively Asian genus), so that family tag had to be ruled out, and they reluctantly agreed that by the rules of botanical nomenclature the first successful bid for each half of the name should stand. So in 1851 the plant was officially dubbed Victoria amazonica. The Queen’s name had been upheld, but attached to an epithet which linked her, in the mind of a nervous Establishment, with a legendary tribe of marauding female savages. The Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, Sir William Hooker, judged that the suffix was ‘well enough matched with one of the Furies, but totally unsuited to be in connection with the name of Her Most Gracious Majesty, whom it is intended to commemorate’. Courtly etiquette triumphed over science, and during the Queen’s life the name V. amazonica was suppressed, and the water lily was always referred to as ‘Victoria regia’. The final whiff of powder came from France. Alcide d’Orbigny, miffed at the way his vague description of the other species of Victoria had been ignored in Britain, decided – in what has the distinct look of a republican snub to the royalist shenanigans over the Channel – to link the Queen’s name with Santa Cruz, the Mexican leader of the Bolivian revolution, when naming his discovery V. cruziana.

This comedy of taxonomic manners was trumped by the drama of coaxing the Queen’s water lily to flower in her home country, something seen as a political imperative. Schomburgk’s first batch of seed had proved infertile. A second batch, purchased from the explorer Thomas Bridges, did germinate, but the two seedlings perished in the ‘dark and cheerless’ days of winter. In some desperation Hooker instructed two Englishmen living in British Guiana to obtain seed, and send it to Kew in phials of spring water. They arrived safely in February 1849, and Hooker, hedging his bets, divided them between Chatsworth, Kew and the Duke of Northumberland’s garden at Syon. At Chatsworth, Joseph Paxton lovingly nursed the seeds in a specially constructed tank kept at 29.5 °C (85 °F). He added a small water wheel to ensure that the lily was ‘deluded into thinking she was on her native waters’. Each of the gardens planted out the seeds in conditions they thought most likely to produce the first flower, and the contest turned into a race ‘as exciting in its day,’ Wilfrid Blunt wrote, ‘as Scott’s and Amundsen’s to the Pole, or the Americans and Russians to the moon’. The plants at Kew and Syon proved incorrigibly shy, but the one in the Great Conservatory at Chatsworth grew so aggressively that its tank had to be enlarged. By the end of September one leaf had a circumference of eleven feet. And on 2 November 1849, Joseph Paxton was able to write excitedly to the Duke (then in Ireland): ‘Victoria has shown a flower!! An enormous bud like a poppy head made its appearance yesterday. It looks like a large peach placed in a cup. No words can describe the grandeur and beauty of the plant.’ The Duke rushed home, and had a flower and a leaf sent to the Queen at Windsor. The historian Isobel Armstrong (though she wrongly attributes the name V. regia to Paxton, who she imagined coined it in an act of loyal fawning) describes ‘the lily enterprise’ as ‘an aristocratic stunt, the deliberate creation of a myth of Brobdignagian botanical birthing is some ways akin to sensational events – the balloon flight, animal freakery – arranged by popular urban gardens’.

Perhaps so, but one of these urban gardens was Kew, and its metropolitan position and loyal fan base ensured that the lily’s flowering was far from an elitist ‘stunt’. By the late 1840s Kew was being visited by up to 10,000 people daily. Admission was free, and the deliberate policy of the director, Hooker – high minded but democratic – was to tempt the ‘frequenters of pot-houses and skittle-alleys in “London’s dirty, crowded pestiferous courts” to pass their morning in Kew’s “perfect paradise”’. The water lily bloomed the following summer, and continued its display right up until Christmas. It proved one of Kew’s greatest attractions to the plant-infatuated citizens of the capital, and Hooker had a much larger tank built to show it off to its best advantage. When it was first exhibited, thousands made the trip to Richmond to experience the full sensuality of its flowering. Kew’s specimens were punctual timekeepers. At about two o’clock each afternoon (the garden fortunately opened to the public at 1 p.m.) the new white buds, the size of tennis balls, began to emit a strong aroma, variously compared to melon, strawberry and pineapple. A few hours later the petals opened and began to change colour to rose pink. Towards ten in the evening they started to close. The flowers’ slow decline continued the following day, when the fading petals became ‘a drapery of Tyrian purple’ until they finally sank beneath the water. Alas, as so often at this time, European horticultural reflexes proved quite inappropriate to the raising of tropical plants, and Victoria, deprived of decent ventilation and flexible heating, had to be moved again.

I’ve yet to witness the full flowering of Victoria. Years ago I kept a daily vigil by the specimen in the tropical biome at the Eden Project in Cornwall, but the flowers were always wide open or tight budded, and I never got to see – or smell – its baroque unfurling. It was some consolation that the legendary Amazonian botanist and onetime director of Kew, Sir Ghillean Prance, was also in the biome on one occasion. He told me how he had witnessed the rite himself in the wild and explained what the extravagant flowering meant for the plant itself. The opening flower buds (in a ‘male’ state at this point) raise their temperature until it is eleven degrees Centigrade higher than the air outside, to add the lure of warmth to the entrancement of smell for the pollinating beetles. Once the insects are inside, the flower shuts, trapping them for twenty-four hours, during which they pick up a mass of pollen on their bodies. The next day the flower opens again, now with the female parts prominent, and beetles make a rapid escape, hopefully flying to another open flower to pollinate it. Meanwhile, beetles that had been trapped elsewhere carry their load of pollen to the fading ‘female’ flowers.

My chance to see the rite of opening, though not of pollination, came when the Amazonian water lily at Cambridge (the nearest botanic garden to my home) began a run of prolific flowering in the late summer of 2013. I got permission to visit the glasshouses after hours, and a promise of an alert call when a bud began to show signs of movement. The Cambridge specimen is V. cruziana, which is hardier in cultivation than its cousin V. amazonica, but shares with it a mischievousness during flowering. Sometimes a likely bud stays teasingly tight; sometimes it opens in an unpredictable rush. When the call came that a flower had opened unexpectedly in the night and another was due that evening, I sped to Cambridge and was escorted to the promising debutant by Alex Summers, the Glasshouse Supervisor. It did seem to be swelling infinitesimally, and there was the faintest smell of pineapple around the pool. But, as they say, a watched kettle never boils, and the bud remained stubbornly cool and closed. By ten o’clock we’d abandoned hope.

But the flowerings here, even when unwitnessed, aren’t futile. In the absence (so far) of tropical scarab beetles in Cambridgeshire, Alex had to stand in as pollinator. Up to his thighs in the outside lily pool, he began pushing cheap paintbrushes into the golden stamens of the previous night’s voluptuous flower. The scene was like a séance: the small circle of expectant viewers, the shadowy backcloth of exotic trees reflected in the glass, the lily lit up by the ectoplasmic green glow from half a dozen smartphones. ‘Channel the beetles, Alex,’ a spectator urged. Well, Alex did, very successfully. A great quantity of pollen was gathered, and transferred the next day to the flower which had opened in its own good time after we’d all gone to bed. A month later I heard from Alex that his beetling had midwifed 194 seeds ‘each similar in size to a ball bearing’.

In the end it was the leaves more than the flowers that were to prove the enduring wonder of Victoria amazonica. Richard Spruce, another Amazonian explorer, seemed prescient in 1849 (the year the lily flowered at Chatsworth) when he gave a thoroughly industrial account of the water lily’s architecture:

The impression the plant gave me, when viewed from the bank above, was that of a number of green tea trays floating, with here and there a bouquet protruding between them; but when more closely surveyed the leaves excited the utmost admiration, from their immensity and perfect symmetry. A leaf, turned up, suggests some strange fabric of cast iron, just taken from the furnace, its ruddy colour, and the enormous ribs with which it is strengthened, increasing the similarity.

The ribs radiate from the centre like the spokes of a wheel, flatten as they extend outwards, and then split up into as many as five forking branchlets, so that at the edge a single rib may have separated into thirty thinner struts. This forking is the key to the leaf’s stability.

Several expensive folios of paintings of the lily’s leaves were published, including one by Walter Fitch, whose lithographs were reduced from originals twenty feet across. The leaves began to influence interior decor, too. Many designers were struck by the distinctive shape and structure of the leaves, incorporating them into chandeliers and gas brackets. One marketed a papier-mâché Victoria cradle. In November 1849, the Amazonian Indians’ custom of bunking down their children on the leaves while they were working was repeated with great success at Chatsworth. The Duke of Devonshire and Lady Newburgh placed Joseph Paxton’s seven-year-old daughter Annie, dressed as a fairy, on one of their home-grown leaves. (Paxton had first tested the leaf, whose tissues were delicate enough to be pierced by a straw dropped from a few feet, with a heavy copper lid, as much out of technological curiosity, I suspect, as concern for his daughter’s safety.) Douglas Jerrold wrote a short doggerel to commemorate the event (‘On unbent leaf in fairy guise,/ Reflected in the water,/ Beloved, admired by hearts and eyes,/ Stands Annie, Paxton’s daughter’) and on 17 November the Illustrated London News published an engraving of Annie afloat. It is a strange and unsettling picture. Annie, far from snoozing like an Amerindian child, is standing stock still, looking shy and awkward. A small scatter of people are leaning on the rails round the lily’s enclosure and gazing laconically, assessing her. The scene is uncomfortably like an auction, with Annie posed in the role of surrogate Indian. The Victorians were quite capable of loving the plant while despising its origins.

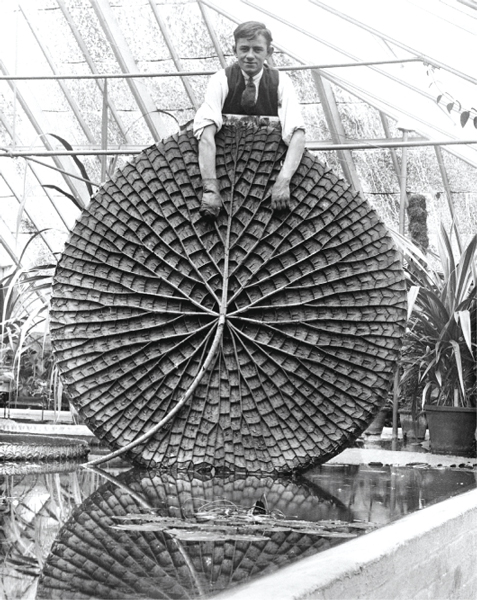

A 1936 photograph showing the extraordinary engineering of Victoria amazonica’s leaf, which had inspired the metal framework of the Crystal Palace.

Meanwhile, Annie’s father’s skill in designing glasshouses had lifted him above his earlier station as a gardener. He had already begun using the ribbing of Victoria’s leaves in remodelling the Chatsworth refugium in which it grew. In 1850 he gave a talk to the Royal Society of Arts about his glasshouse, during which he demonstrated, and gave credit to, the structure of the water lily’s leaves: ‘You will observe that nature was the engineer in this case. If you will examine this, and compare it with the drawings and models, you will see that nature has provided it with longitudinal and transverse girders and supports, on the same principle that I, borrowing from it, have adopted in this building.’ Shortly afterwards he won a competition, set up by Royal Commission, to design and bring into being a building to house the Great Exhibition planned for London in 1851. The result was the Crystal Palace. In designing it Paxton used Victoria’s device of developing a few main ribs into a series of thinner struttings, bound to one another by many fine cross-ribs. No large building had ever been built like this chimera of steel and cellulose before, but every large glass building since ultimately derives from it.