WOODEN MANIKINS: THE CULTS OF TREES

The Palaeolithics’ dawning interest in the metaphor of the branch was picked up later in the Middle East, and it’s not without irony that the first image of a significant tree is from Mesopotamia, springboard of the agricultural revolution that was to destroy most of the world’s forest over the next 5,000 years. It’s on a Sumerian seal from circa 4500 BC and shows a tree of life between two gods. The female goddess is probably Isis, and she has a snake, a symbol of water, beside her. The tree is smaller than the gods and appears to be on some kind of stand, but it is obviously a palm, with symmetrically arranged leaves and two prominent drooping dates. Whether the palm was regarded as a minor god itself, or just one of the gods’ sacred accoutrements is uncertain. Almost identical arrangements of layered branches, occasionally with date-like appendages, are carved round the fonts in many Christian churches, again adjacent to sacred water, and are usually regarded as representations of Eden’s Tree of Life.

It was just such an idealised notion of ‘the tree’ – a monumental, branching manikin (children draw humans as simple trees, just as they paint faces on flowers) – that placed this group of long-lived plants at the centre of many creation myths and models of the universe, especially in societies which had already generated their own branching and layered hierarchies. Joining earth and sky, capable of outliving not just individual humans but whole civilisations, they are obvious symbols of the more-than-human, and many religious narratives have played with analogies between the arboreal seasons and spiritual cycle of death and rebirth. China has the Kien-mou, the 100,000-cubit tree of life. The Buddhist Tree of Wisdom’s four boughs are the source of the four rivers of life. One of the best known is the Norse ‘World Tree’, Yggdrasil, usually imagined as an ash, and first appearing in Norse legend in the early medieval period, though presumably of older origins. Yggdrasil is one of the more intriguing trees of life, since it has some relation to the real ecology of the forest. In the myth it is the focal point of the transmutation of the sun’s energy and of a set of reciprocal relations with other organisms.

As for the Tree of Life in the Old Testament, it has no such creative role, and no real-world botanical model. It certainly wasn’t a bearer of apples, a species unsuited to the parched environments of the Holy Land. But a sense of its sheer treeness – its durability, rootedness, continuity, powers of regeneration – is emblematic of the symbolic power of all woody growth. And as a motif, it crops up time and again in Christian mythology. Its complete adventures, in a myriad local versions, has the tree supplying most of the wooden artefacts of Christian iconography. The story starts when Seth, Adam and Eve’s third son, returns to the Garden of Eden – still there apparently, like the abandoned estate of a derelict house – and begs some seed of the Tree from the angel on duty at the gate. He plants it in his father’s mouth as Adam is dying. It grows from his mouldering body into a tree which metamorphoses across species and across sacred history. It supplies planks of ‘gopher wood’ (possibly cypress) for Noah’s ark, and an unspecified branch for Moses’ omnipotent staff (which at one point changes back into a serpent). Later it is a cedar felled for use in the construction of King Solomon’s temple, and a wooden bridge for the visiting Queen of Sheba to cross its encircling moat. When the temple is destroyed, its timber, after more fantastical coincidences and transformations (it occasionally reappears as a plank in Joseph’s workshop), ends up forming the beams from which the Cross is made. The tree of life becomes the tree of death, and then the wooden symbol of redemption.

An elaborate portrayal of Yggdrasil, the Norse Tree of Life, from a seventeenth-century Edda manuscript.

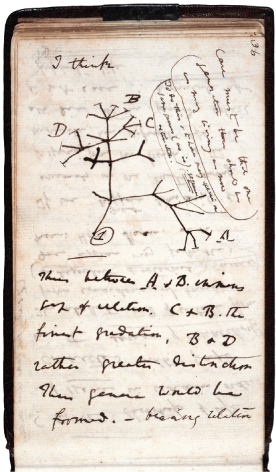

It is also the form of tree growth – the repeated forking and dividing, the way in which the structures of bodily trunk, branch and leaf echo each other – that has helped make trees such universal symbols. Branching is also the pattern of the lineages of living things. The biblical Stem of Jesse is a tree, a family tree. Each ‘begat’ is a node where a new branch or twig emerges. Two thousand years later Charles Darwin, whose ideas challenged the very core of fundamentalist Christian theology, schematised the progress of evolution in a roughly sketched family tree in his notebook for July 1837. It bears a remarkable resemblance to the twiggy scrawls on Palaeolithic bones. Later he included a more refined sketch as the one illustration in The Origin of Species. Kingdoms, individual dynasties and families, sprout out as branches, and occasionally die out or divide again into newly evolved groupings. Darwin himself wrote an eloquent commentary on his tree, abbreviated here:

The affinities of all beings of the same class have sometimes been represented by a great tree. I believe this simile largely speaks the truth. The green and budding twigs may represent existing species: and those produced during former years may represent the long succession of extinct species … As buds give rise by growth to fresh buds, and these, if vigorous, branch out and overtop on all sides many a feebler branch, so by generation I believe it has been with the great Tree of Life, which fills with its dead and broken branches the crust of the earth, and covers the surface with its ever-branching and beautiful ramifications.

Darwin’s Tree of Life is both a literal description of the development of a real tree through time, and the grandest of metaphors about the whole of creation.

Our modern preoccupation with the tall and stately and decoratively antique was a later development, coinciding with the period of history when trees began to be owned, and used as symbols of status and wealth. At the same time they began to be judged by human values. The deliberate creation of plantations replaced natural regeneration as a means of producing new trees. The straight column – architecturally classical and commercially valuable – came to be admired in preference to the gnarled and self-sprung native. The fact that trees have perfectly adequate reproductive systems began to pass out of popular consciousness. We now believe we have to plant them to guarantee their presence on the earth. A thoroughgoing anthropomorphism continues to infect our judgement of their form, too. Natural signs of ageing are interpreted as disease, and disorderly growth as an indication of inferiority. Both are frequent preludes to arboreal cleansing.

None of this bore any relation to how I first experienced trees as a child, hunkering down in the root pits of wind-thrown chestnuts and spending days up in the tangled attics of cedars. I saw their living interiors, not their painterly surfaces. In the chapters that follow, using some half a dozen tree species, I have set down images and cultural expectations against their own ingenious, resilient and often rowdy behaviour.