Chapter 6

Creating Your Action Plan

“The secret of getting ahead is getting started.”

—Mark Twain, author

C

ongratulations are in order because you’ve reached the last chapter of this book and now know more than most people about how to achieve success. Because of this, you are significantly closer to achieving your goals. For example, you know that:

• Your IQ and grades on tests of academic ability are not enough to guarantee your success and, if you over-rely on them at the expense of developing other skills, may even hold you back.

• Your positive beliefs—particularly those related to having a growth mindset and positive core self-evaluations—can propel you forward toward your goals. And having a growth mindset can even protect people from some of the negative effects of stereotyping and discrimination.

• Assuming that someone’s talents are natural or that his or her success came easily is a mistake. It takes years of mindful, deliberate practice for one to develop what may look like natural ability.

• Conscientiousness is one of the most significant predictors of academic and work success, good health, and longevity.

• Gritty people have passion and perseverance, and they focus on a

single

long-term goal

.

• Sometimes it can be healthier for you to cut your losses and switch to a new goal if a dream of yours is no longer worth the sacrifice or you have found something significantly more meaningful.

• Your

social capital

is critical for achieving your goals. You can build it by developing your self-awareness, brand, and ability to energize others, as well as by managing the size, structure, and diversity of your network.

These lessons will serve you well regardless of whether you want to be a star performer in a particular area, reach the most senior levels in your field, or make a quiet contribution to the world through your everyday actions. Even if you don’t yet know what your long-term goal is, you can still take steps to discover a meaningful direction in your life and prepare yourself to act quickly and thoughtfully once you are ready to commit to a particular path.

In this chapter, you will have the opportunity to turn what you know about achieving success into action. You’ll first learn two strategies that are important to your action plan for success: developing your willpower and making yourself luckier. You’ll then be guided through a process by which you can identify an important life goal and develop your personalized plan for achieving that goal.

Action Plan for Success, Strategy One: Develop Your Willpower

Willpower matters in your action plan for success because self-control—the ability to delay gratification and resist impulses—is a hallmark of successful people. Researchers have found that the ability to self-regulate behavior significantly predicts performance, wealth, health, and well-being.[

1

] Conscientiousness, grittiness, and commitment to developing an expertise through mindful,

deliberate practice all require the ability to avoid distractions and stay focused on what matters most, day after day and year after year. Likewise, developing a network of mutually supportive relationships requires the self-discipline to reach out beyond the comfort and convenience of engaging with the people you already know or who are easiest for you to meet.

In Chapter 3, you learned that willpower is a limited resource and that you need to invest it wisely. Although there are limits to our willpower, there are ways that we can increase it and use it more wisely. Researcher Veronica Job and her colleagues have conducted several studies in which they found that people who

believe

that willpower is renewable and “nonlimited” are likely to perform better than those who believe that it is easily depleted and “limited.”[

2

] In one study, students who believed that willpower is nonlimited were less likely to procrastinate and more likely to achieve higher grades than those who believed that willpower is limited, particularly in high-demand situations that required a lot of self-discipline. This is because people who believe that willpower can be increased are inclined to develop and use strategies to increase and channel their willpower toward important goals, whereas people who believe it is limited are more likely to quit before their they reach their actual limits. According to Job and her colleagues, like a muscle, the more one uses techniques for self-control, the stronger one’s willpower becomes.

Social psychologist Roy Baumeister found that one of the easiest techniques for managing your willpower is to automate your behavior so that you often don’t have to engage your self-control when trying to achieve your goals.[

3

] Two of the easiest and most effective ways to automate your behavior are creating bright lines and developing good habits

.

Automating Your Behavior: Create Bright Lines

A bright line is a simple, explicitly stated, and unbreakable

rule

or standard that you create based on your individual goals.[

4

] Examples of bright lines include: “No cell phones at the dinner table,” “Always stop what you’re doing and listen when someone is talking to you,” “Don’t eat dessert on weekdays,” “Work out every morning between 7:00 and 8:00,” “Always get to meetings five minutes early,” “Hold only 30-minute meetings,” “No cruising the Internet for fun before 9:00 p.m. or after 10:00 p.m.,” and “Write for at least three hours before noon every day.” A bright line is specific rather than general. You don’t create a bright line by saying something like, “I will eat healthier food.” You create a bright line by saying, “I will fill my plate with three-fourths vegetables at every dinner,” and you then adhere to this rule all the time and without question.

Bright lines provide several advantages. First, you don’t have to spend time and effort debating with yourself or others about what you should be doing (e.g., “Should I or shouldn’t I fill my plate with pasta?”), because you’ve already made the decision (to fill your plate with three-fourths vegetables) and you just do it (at every dinner, regardless of what you’re eating). Second, by adhering to these bright lines, you’re able to conserve your willpower so that you can use it for complex decisions that take more effort and aren’t easily solved by implementing simple rules. Third, your willpower is less likely to be depleted if you are following your own bright line rules because you’re less likely to feel as though you are using up willpower by actively resisting temptations or by following someone else’s rules.[

5

]

Automating Your Behavior: Develop Good Habits

A habit is a routine behavior that we regularly engage in, typically without thinking about it. Drinking a cup of coffee or tea shortly after you wake up in the morning, saying “I love you” to your

family every time you leave the house, checking your email and Facebook before you start the work day, interrupting people when they speak, and watching television for a few hours before bedtime are all habits. Unlike with bright lines, we don’t typically choose our habits, nor do we explicitly state that we will engage in them without question. Instead, with habits we simply repeat a behavior often enough until it becomes automatic and hard to stop. Good and bad habits tend to be triggered unconsciously by particular contexts (e.g., morning = coffee, office = check email, stress = bite nails). But although most habits evolve unconsciously, you can proactively create good habits that help you and others achieve important goals.

One way to do this is to manage the

context

so that it’s more likely to trigger good habits. Not having your phone in your pocket makes it less likely you’ll want to check it for messages when you should be paying attention to what’s going on around you. Not having sugary treats in the refrigerator makes it less likely you’ll want to eat them and increases the chance that you’ll make healthier food choices. Not having a television in the bedroom will make it less likely you’ll want to stay up late watching television. Getting your workout clothes ready in the evening makes it more likely you’ll put them on and work out in the morning. Having money automatically taken out of your paycheck and put in your retirement account makes it more likely you will increase your retirement savings. Making regular appointments to meet with a coach makes it more likely that you’ll practice and work harder than you otherwise would. Working in a place with no distractions makes it more likely you will focus on what you need to accomplish.

A

keystone habit

is one that impacts multiple parts of your life. For example, if you develop the discipline to exercise, you are more likely to eat healthfully and to find the willpower within you to be more disciplined in other areas of your life as well. If you start arriving at meetings five minutes early and use that time

to talk to people from different parts of the organization, you may start arriving at other events in your life early and going out of your way to reach out to people you wouldn’t normally talk to. Identifying and changing a few keystone habits—habits that are likely to cause a chain reaction that develops other productive behaviors, ideally in multiple parts of your life—can have a big impact on your ability to achieve your goals.

Small Wins

Keystone habits are particularly effective because they tend to be

small wins

. Researcher Karl Weick explains that a small win is a small, concrete, and successfully- implemented outcome that by itself may not seem important. But as

New York Times

journalist Charles Duhigg explains in his book

The Power of Habit

:

a huge body of research has shown that small wins have enormous power, an influence disproportionate to the accomplishment of the victories themselves. ‘Small wins are a steady application of a small advantage,’ one Cornell University professor [Karl Weick] wrote in 1984, ‘once a small win has been accomplished, forces are set in motion that favor another small win.’[

6

]

Weick explains that “small wins fuel transformative changes” for several reasons.[

7

] Because they are more achievable, controllable, and predictable, small wins are much less disruptive than trying to make big changes. We feel less overwhelmed by the enormity of a long-term goal if we break it up into small steps. Since we are less overwhelmed by tackling small wins, our efforts are less likely to be hijacked by anxiety-based behaviors such as procrastination and performance anxiety. And with each small win or small failure, we can learn something new that we can apply to the next change we want to make.

For example, you may not be in a position to go to school full-time, but you may be able to take a few classes in the evening,

perhaps at a local community college, and then transfer the credits to a four-year college later. You may not be able to take on the responsibilities of a promotion at this time, but you can volunteer to be on committees that give you the perspective, skills, and contacts that will set you up to be ready for a promotion when the time is right. You may not be able to work out for an hour every morning, but you may be able to do 10 minutes of exercise while waiting for your children to get ready for school. You may be too exhausted after long days at work to engage in high-effort activities with your children, but you can curl up on the couch with them and create a tradition of watching a favorite television show together that you will all enjoy in the moment and look back on fondly.

Warren Buffett acknowledges that he was socially inept and extremely afraid of public speaking when he was a young man. To conquer his fear of public speaking, he took a Dale Carnegie Course called “How to Win Friends and Influence People” and soon afterwards taught at a local college to immediately practice what he had learned.[

8

] Over the years, Buffett has become so at ease with public speaking that he seems like a natural, not only in formal presentations but in informal conversations as well.

Another advantage of small wins is that they are more likely to fit the realities associated with pursuing long-term goals. If you pursue several small wins rather than invest all your time and effort into one long-term strategy, you are more likely to be able to take advantage of opportunities that unexpectedly arrive and be able to switch tactics if some parts of your plan are blocked. As long as the small wins are all headed in the same direction you’ll be making visible progress, and eventually these small wins are likely to merge into a coherent and impactful result. As Weick explains, “small wins are like short stacks.”[

9

] To illustrate the meaning of this, imagine that you have to count through a box of paper until you reach exactly 1000 pieces. If you try to count non-stop from 1 to 1000, you are likely to be interrupted and make

mistakes, thereby causing you to start over many times, increasing your frustration, and making it less likely you’ll efficiently achieve your goal. But if you create short stacks of 50 or 100 sheets of paper, you are likely to reach 1000 pieces of paper more quickly because you will be able to quickly find your place if you get interrupted or make a mistake.

Psychologist Angela Duckworth explains that “. . . the most dazzling human achievements are, in fact, the aggregate of countless individual elements, each of which is, in a sense, ordinary.” She quotes sociologist Dan Chambliss as stating that:

Superlative performance is really a confluence of dozens of small skills or activities, each one learned or stumbled upon, which have been carefully drilled into habit and then are fitted together in a synthesized whole. There is nothing extraordinary or superhuman in any one of those actions; only the fact that they are done consistently and correctly, and all together, produce excellence.[

10

]

The important points to remember about willpower (the first strategy in your action plan for success) are:

• Developing and implementing your action plan will require a lot of willpower.

• Although willpower isn’t infinite, you have much more than you think.

• Automating effective behaviors by creating bright lines and helpful habits helps you conserve your willpower so that you can use it for making tough decisions and engaging in complex behaviors that can’t be automated.

• Creating and accumulating small wins is a far more effective strategy for transformative change than tackling a large goal all at once

.

Action Plan for Success, Strategy Two: Make Yourself Luckier

Despite all the planning and effort you’ll have to put into developing and implementing your action plan for success, you can’t control everything. Good luck and bad luck will inevitably join you throughout your journey through life. Actor Bryan Cranston won multiple Emmy awards for his portrayal of Walter White in the television series Breaking Bad. He got the part not only due to the talent he developed over years of hard work and experience, but also because he was lucky that Mathew Broderick and John Cusack turned down the role; because only then did producers offer the role to Cranston.[

11

] Pilot “Sully” Sullenberger was unlucky when the flock of Canadian geese flew into the engines of the airbus he was piloting, but he was lucky that this happened on a clear, sunny day rather than during a blinding blizzard, increasing the chance that he would be able to land the plane safely. When Sonia Sotomayor decided to be the first in her family to go to college, she was lucky that her friend Kenny encouraged her to apply to Princeton, where she then attended college and thrived.

Although luck certainly played a part in these cases, so did years of preparation. Cranston had been working as an actor for twenty years before being cast as Walter White. Sullenberger had over 45 years and 19,000 hours of experience as a pilot before his talents were tested after the bird strike. And Sotomayor studied hard for many years to earn good grades in school before she applied to college. As famed chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur said over a century ago, “chance favors the prepared mind.”

Fortunately, research suggests that you can make yourself luckier. In a 10-year study of what makes some people luckier than others, researcher Richard Wiseman identified several things that lucky people do, including creating chance encounters, noticing things that other people miss, using positive expectations to create self-fulfilling prophesies, and adopting “a resilient attitude that

transforms bad luck into good.”[

12

]

Making Yourself Luckier: Create Chance Encounters

Lucky people create chance encounters by breaking their daily routines. If you do the same thing day after day, it’s unlikely that you’ll get inspired with new ideas or meet different people who can give you new information, contacts, and opportunities. You can increase your luck if you sometimes take an alternative route to work, have lunch with different people, do your work in an unusual setting, or read different kinds of books. In his book

The Luck Factor

, Wiseman gives the example of a man who had a habit of talking to the same kinds of people whenever he went to social events. He broke this routine by using a unique technique in which he would pick a color—say, blue or red—before every event and then speak to people who were wearing that color.

Making Yourself Luckier: Notice What Other People Miss

Lucky people also

notice

what other people may miss. In 1928, Alexander Fleming, a brilliant but sometimes messy scientist, was researching the properties of staphylococci, which is a type of bacteria that causes staph infections. Before leaving for a month-long August vacation, he inadvertently left stacks of petri dishes containing colonies of staphylococci on a bench in his laboratory. When he returned on September 3, he noticed that one of the petri dishes was contaminated with mold. Rather than quickly discarding the tainted petri dish, he looked more closely and noticed that the staphylococci surrounding the mold were destroyed. He discussed his finding with his assistant, cultivated the mold in an uncontaminated environment, and found that the mold obliterated several different kinds of bacteria, many of which could lead to life-threatening infections like scarlet fever and pneumonia. He called his accidental discovery “mould juice” for several months until he figured out that the mold came from the genus Penicillium. He renamed the substance “penicillin,” and

in 1945 was awarded the Nobel Prize for his discovery, together with Howard Florey and Ernst Boris Chain who figured out how to mass produce the life-saving antibiotic.

Making Yourself Luckier: Turn Bad Luck into Good Luck

Lucky people believe that what initially looks like bad luck can turn out to be very good luck, so they are more likely to take actions to turn this belief into reality. Warren Buffett was rejected by the Harvard Business School, and he says it was one of the luckiest things that ever happened to him. Shortly after he was turned down by Harvard, Buffett applied to and was accepted to Columbia University where he took a course from one of his idols, economist Benjamin Graham who wrote the book

The Intelligent Investor

. Buffett had read Graham’s book as a teenager (he began reading investing books when he was 10 years old), and the book significantly influenced his views on investing. Buffett went on to become one of the most successful investors of all time. As the old adage goes, good luck happens when preparation meets opportunity.

Creating Your Action Plan

Now it’s time for you to create your action plan for achieving success. Researchers have found that you’re more likely to be focused, motivated, persistent, and successful in achieving your goals if you:[

13

]

• choose a goal that is meaningful to you and makes a contribution to others;

• believe the goal is attainable;

• visualize what success will look like, as well as the steps you’ll need to take to achieve it;[

14

]

• write down your action plan;

• make a public commitment; and

• measure your progress

.

In one study, researchers found that MBA students who committed to specific and challenging learning goals such as learning to network or mastering a specific set of courses had higher GPAs and greater satisfaction with school than those who focused on longer-term performance goals (completing the MBA program and getting a job).[

15

] Another study involved 149 working adults in a variety of professions (e.g., managers, educators, health care professionals, artists, attorneys, and directors of nonprofits) from different countries (e.g., the U.S., India, Belgium, England, Australia, and Japan). The researcher there found that 70% of participants who wrote down their goals and strategies for achieving those goals, shared their plans to friends, and sent the friends weekly progress updates reported making progress toward their goals compared with 30% of those who didn’t write down their plan and share it with others.[

16

] Not a bad payoff considering that writing an action plan and holding yourself accountable costs nothing and takes only a little of your time. You can create your own action plan by taking the following three steps that I’ve categorized as heart, head, and hands. And you can find an accompanying template for writing out your action plan for success in the Appendix of this book.

Action Plan Step One (“Heart”): Create Your Pie Chart

Focusing on your overall life goals is the “heart” of your action plan. It involves considering your values, identifying what is most meaningful to you, thinking about how you want to make a contribution to others, and reflecting on how you want to spend the limited days you have on earth. To focus on the big picture and identify your overall life goals, first draw a pie chart in which you divide the pie into slices, with each slice focusing on a specific goal that is important to you. The size of each slice will reflect its importance to you. I suggest that you start by dividing the pie into at least three large slices representing three major life categories, for example work, career, and well-being. Each of these three main slices should then be divided into smaller slices,

with the smaller slices representing goals you want to achieve within the major life categories.

For example, the “work” category may include goals (slices) such as getting better results at work and developing your expertise. The “career” category may include goals (slices) like getting promotions, earning salary increases, enjoying your job, having job flexibility, working part-time, and retiring at a specific age. And the “well-being” category may include goals (slices) such as becoming or staying healthy, being happy, growing spiritually or psychologically, having financial security, spending time with your friends and other people you love, participating in your religious and other communities, and investing in things you care about outside of work. It’s your life, so you get to decide what slices should be in your pie and how big each slice should be. As you create your pie chart, I recommend that you don’t worry about making the slices of the pie the perfect size, because perfection isn’t the goal of this activity.

I also recommend that your pie chart represent your goals for the next 5–10 years, because your pie chart is likely to look different at different stages of your life. See the illustration in Figure 6.1 for an example. Some people even like to create two pie charts, one for the present and one for the future. This is your life and your action plan, so you can adapt this activity any way that meets your needs

.

Figure 6.1.

Your Life Goals

Action Plan Step Two (“Head”): Identify One Goal to Work On

Identifying the goal you want to work on is categorized as the “head” of your action plan. It requires thinking carefully about your priorities, what others need from you, the feasibility of the changes you want to make (e.g., costs vs. resources), and the trade-offs that you’re willing to make in order to achieve your longer term goals. This is where you take personal responsibility for your choices. Once you have created your pie chart displaying your life goals, choose one goal (one slice from the chart) that

you want to work on in the short term. For example, you may want to focus on developing a particular expertise, or getting a promotion, or spending more time with family, or taking care of your health. You are more likely to invest in making a goal-oriented decision work if it is of your own choosing rather than imposed on you. And remember that you can’t do everything all at once, but—as you learned about keystone habits—if you select the change you want to make carefully, the progress you make in one part of your life can have a ripple effect into other areas of your life.

As tempting as it may be for you to strive for “work-life balance,” I recommend against using that as a goal because “balance”—at least for most people—is elusive. Life simply doesn’t fit into equal sized categories that demand the same amount of time, effort, and attention at every stage of your life. Frankly, you may be able to achieve “balance” for a while. But then something is likely to happen that will throw your life out of balance, and it may not be easy or possible for you to get the balance back. If you spend all your time trying to balance your life, you may not be able to appreciate the life you have, as imbalanced as it is.[

17

] Instead of striving for balance, I recommend that you strive for a meaningful life and a life well lived, and make your choices accordingly.

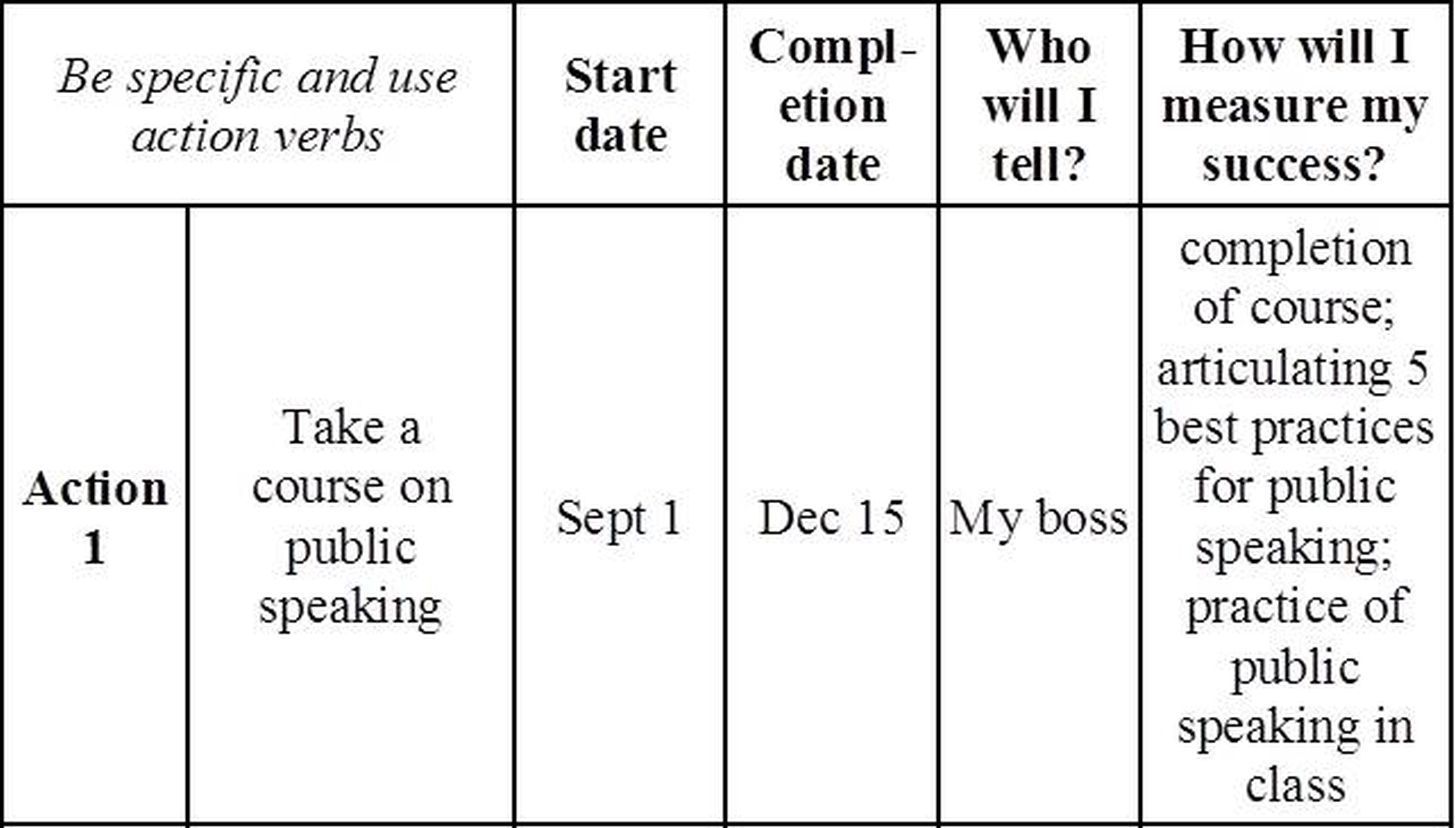

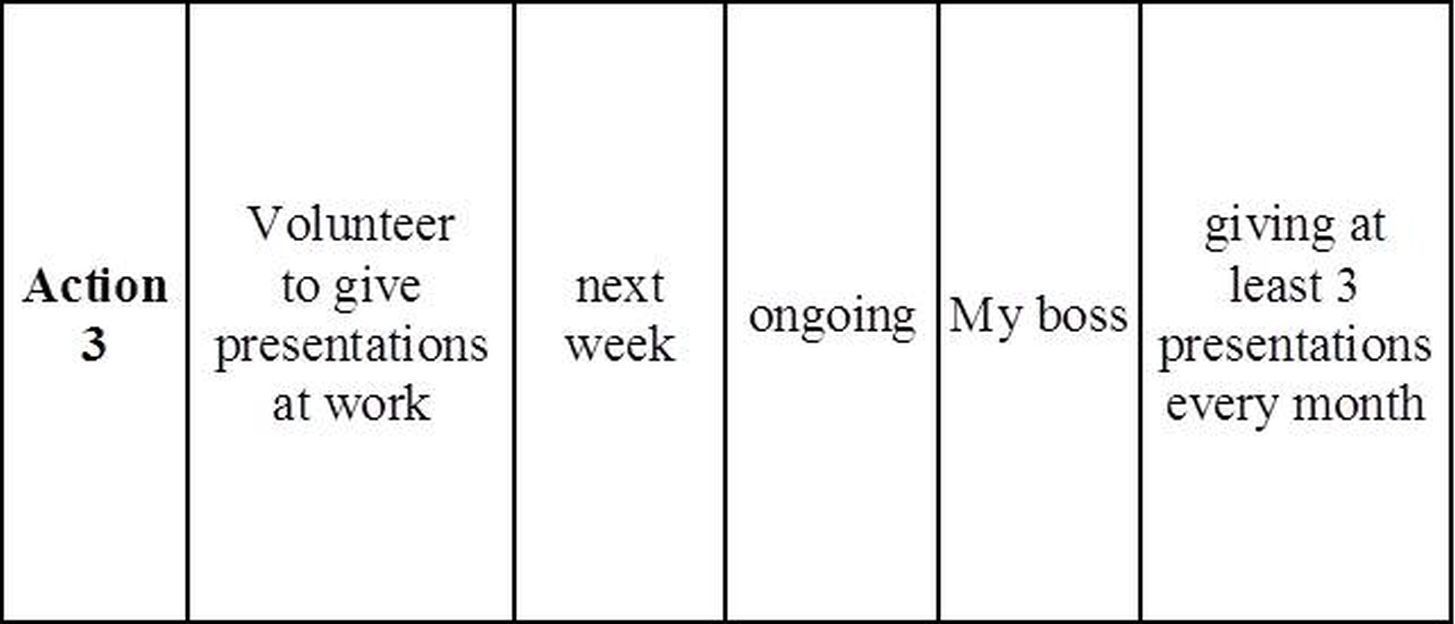

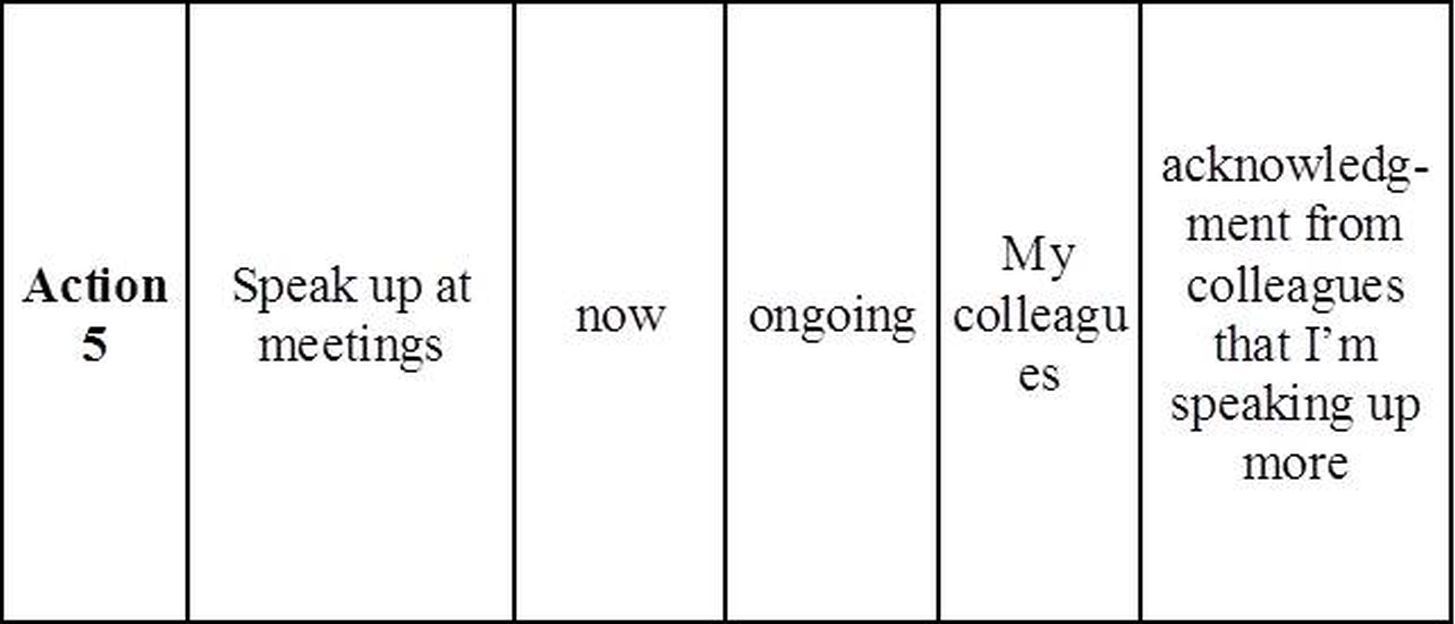

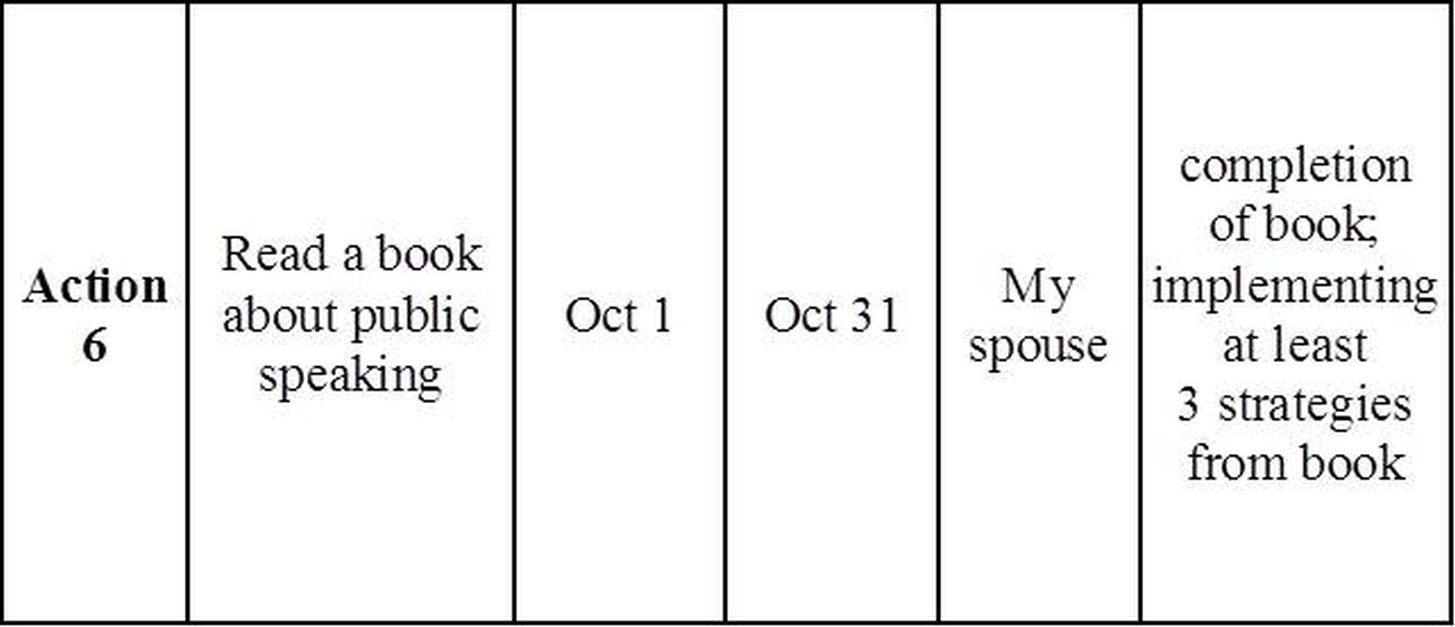

Action Plan Step Three (“Hands”): Identify the Specific Steps You Will Take

The next step in creating your action plan for achieving success is to write down specific steps you will take to achieve the goal that you identified, focusing on small wins. This is the “hands” part of your action plan: writing down what you will do, how you will do it, when you will do it, how you will measure your success, and who you will tell about your plan. Psychologist Robert Cialdini found that “People live up to what they write down.”[

18

] See Figure 6.2, at the end of this section, for an example of a completed “

hands” portion an action plan. And remember to also see the Appendix of this book (“Template for Creating Your Action Plan”), which includes a blank table you can use to write down the specific details of the “hands” portion of your action plan.

After you develop the hands portion of your action plan, don’t keep adding new tasks to the plan over time without removing old ones. For everything you commit to start doing, commit to stop doing at least one other thing. Remember that what you stop doing can be as important to the success of your action plan as what you start doing. A manager who was taking one of my MBA classes once told me that she uses “the Coco Chanel rule for accessorizing” as a metaphor for managing her life, explaining that the late French designer Coco Chanel’s rule was to remove one accessory whenever adding another.

Figure 6.2.

Action Plan Worksheet (the “Hands”)

Goal:

Enhance my communication skills.

Figure 6.2.

Action Plan Worksheet, Continued

Question A.

What will I stop doing so that I can focus more of my time and effort on my most important goal?

I will reduce the time I spend cruising the Internet for fun

from two hours to 30 minutes each day.

Question B.

What can I automate to make it easier to achieve this goal?

I can develop a standard format for my presentation slides that makes them interesting so that I don’t have to create interesting slides from scratch each time I am putting together a presentation. I can also create a checklist for how to tell an engaging story, and can use that checklist until telling an engaging story becomes instinctive.

Question C.

In what ways will the actions I take positively affect multiple parts of my life?

It will help me be more comfortable speaking up and giving presentations at work, more communicative with my family, and more poised at social functions. It will help me be a good mentor to others because I’ll be willing to share what I learned with them. Giving presentations at work will help me meet new people and build my network.

A Few Pieces of Advice

The first piece of advice is to remember to be compassionate with yourself as you pursue your goals.[

19

] Researchers have found that everyone experiences “high-variance performance,” which means that no one succeeds at all they do, all the time, in every part of life. The variance in performance (e.g., sometimes you win and sometimes you lose) increases with the complexity of your goals and your life. Researcher Jane Dutton and her colleagues have found that setbacks and feeling badly about them are not only inevitable, but also necessary for growth because they give us opportunities to learn.[

20

] Being compassionate—for example, kind and forgiving—with ourselves when we fail or don’t live up to our own or others’ expectations is important because it gives us

the strength and courage we need to be resilient, the motivation to keep trying, and the willingness to adjust our goals as we learn, change, and grow.

Karl Weick, citing social scientist Fritz Roethlisberger, advised:

People who are preoccupied with success ask the wrong question. They ask, “what is the secret of success?” when they should be asking, “what prevents me from learning here and now?” To be overly preoccupied with the future is to be inattentive toward the present where learning and growth take place. To walk around asking, “am I a success or a failure?” is a silly question in the sense that the closest you can come to an answer is to say, “everyone is both a success and a failure.”[

21

]

My second piece of advice is, when you have achieved the success you desire, be helpful to those who come after you. Melinda Gates, cofounder of the Gates Foundation, wisely said:

If you are successful, it is because somewhere, sometime someone gave you a life or an idea that started you in the right direction. Remember also that you are indebted to life until you help some less fortunate person, just as you were helped.

I wish you all the best on your journey in life, not only because you deserve to achieve the success you desire, but also because the world needs your talents and contributions. Safe travels, and enjoy the trip.