TWO

Surrender in Chicago

CITIES’ RIGHTS AND THE LIMITS OF FEDERAL ENFORCEMENT OF SCHOOL DESEGREGATION

In New York and Chicago, you don’t have separate but equal schools. You have integration.

—U.S. REPRESENTATIVE EMANUEL CELLER, 1964

When the United States Office of Education was pressured into restoring Federal funds to Chicago’s segregated public school system, it represented the first abject surrender to the principle that separate but equal is wrong in the South, but acceptable in the North—particularly if a city can muster enough Northern politicians and educators with a segregationist mentality to practice this shameful hypocrisy.

—ADAM CLAYTON POWELL, 1965

ON JULY 4, 1965, AFTER months of school protests and boycotts, civil rights advocates in Chicago filed a complaint with the U.S. Office of Education charging that the Chicago Board of Education violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The implications of the charges were extremely serious. If Chicago had violated Title VI, which gave the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) authority to withhold funds if school districts failed to comply with rules against school segregation, the city stood to lose $30 million in federal money. Drawing on evidence from an array of published reports and their own investigations, the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations (CCCO) told federal officials that 81 percent of elementary schools and 73 percent of high schools were racially segregated, with 90 percent of black students attending segregated schools. These blacks schools were more acutely overcrowded, had a higher percentage of noncertified teachers, and offered fewer honors classes than white schools. The CCCO presented its case in no uncertain terms. “The Chicago Board of Education has deliberately segregated the city’s public school system,” a CCCO report began. “Neither segregation nor integration just ‘happens.’ Each is deliberately stalled or prevented. The school board, acting under advice of its general superintendent, pursues a deliberate policy of segregation.”1 In its letter to the Office of Education, the civil rights coalition argued that Chicago’s schools were unconstitutionally segregated: “When a public body such as the school board draws boundary lines such as it has in the past, and is likely to do again, that produce segregation, then what we have is not de facto segregation—it is de jure segregation.”2 In addition to calling the innocence of Chicago’s school segregation into question, the complaint correctly predicted that Chicago’s evasion of school desegregation could have a national influence. “We are further persuaded that the ways and means of creating and perpetuating segregation in Chicago may become the handbook for southern communities seeking to evade the 1954 Supreme Court ruling. We are confident that federal intervention in this matter, through the withholding of funds, will help underline the high fiscal cost, as well the immeasurable social cost, of segregation to Chicago and to the rest of the nation.”3

When HEW received the Chicago complaint, the agency was focused on school segregation in the South. When HEW’s Title VI enforcement guidelines were announced in the Saturday Review in March 1965, the magazine made this southern focus clear: “[Saturday Review] hopes that Southern school authorities will find these guidelines helpful in making the fateful decisions that confront them. And Northern readers will find, in the calm words and careful analysis of the memo, a clear view of the issues as they have evolved to date.”4 Titled “Title VI: Southern Education Faces the Facts,” this introduction to Title VI addressed northerners as innocent readers following a story taking place elsewhere, suggesting the disbelief that greeted the prospect of federal funds being withheld from Chicago for violating the Civil Rights Act.

HEW briefly withheld $30 million in federal funds from Chicago in fall 1965, finding the city’s schools to be in “probable noncompliance” with Title VI’s antidiscrimination provisions. Facing pressure from Mayor Richard J. Daley, Senator Everett Dirksen, Illinois congressmen, and President Lyndon Johnson, HEW’s case in Chicago quickly unraveled, exposing the limits of federal authority in the face of school segregation in the North. “Mayor Daley ostensibly supported the Civil Rights Act and all the Democratic Congressmen from Illinois . . . voted for it,” CCCO leader Al Raby said after the federal funds were restored just five days later. “Yet they are the first to squeal like stuck pigs when the bill is enforced in the North.”5 What Raby saw as a contradiction was actually a logical outcome of the decision to include an “antibusing” provision in the Civil Rights Act that excluded desegregation to correct “racial imbalance” in the North. The Chicago Tribune, which staunchly opposed school desegregation in the city, regularly quoted Title IV, section 401b, of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (“‘Desegregation’ means the assignment of students to public schools and within such schools without regard to their race, color, religion, or national origin, but ‘desegregation’ shall not mean the assignment of students to public schools in order to overcome racial imbalance”) to support their case against school des-egregation.6 If New York’s “antibusing” protests encouraged northern congressmen to exempt northern schools from the Civil Rights Act, HEW’s surrender in Chicago encouraged school officials and politicians to maintain positions of resistance and noncompliance with regard to school desegregation.

“DOWN WITH WILLIS”

Civil rights activists and parents in Chicago, like those in New York, investigated school policies across a massive school system with the goal of making school segregation an issue that could not be ignored. In December 1956, after several months of research, the Chicago branch of the NAACP released a survey charging that “school district boundaries . . . follow and reinforce racial segregation,” that the percentage of inexperienced teachers “in the predominantly Negro districts is shockingly and disproportionately higher than in predominantly white districts,” “that the wide spread belief that Chicago’s residential segregation pattern prevents integration within the public schools is a myth, and that the Chicago public schools can be substantially integrated within a short period of time if there is the will to do so.” The NAACP hoped the survey would force the school board to acknowledge the existence of school segregation and make a commitment to foster integration. Pointing to New York’s approval of a policy of school desegregation, Chicago NAACP president Willoughby Abner said, “It is our firm opinion that nothing short of the adoption and implementation of a forthright policy of racial integration within the Chicago public schools can correct this situation.”7

In the absence of a reply from the school board, the Chicago branch tried unsuccessfully to get the state’s school construction bonds to require new schools to be placed to encourage desegregation and asked the school board to bus students from overcrowded black schools to white schools with empty seats.8 A February 1958 article in Crisis, the national NAACP journal, highlighted many of the Chicago NAACP’s statistics regarding educational inequality in the city. They estimated that over 90 percent of black elementary students and 70 percent of black high-school students attended segregated schools. Noting that black students made up 80 percent of students in overcrowded schools with “double shifts,” the article asked “whether the school time lost to [the] Negro child is not almost as great in Chicago as it is in Mississippi.”9 These statistics buttressed the argument that school segregation was not accidental and was not out of the control of the school board: “In cost and quality of instruction, school time, districting and choice of sites, the Chicago Board of Education maintains in practice what amounts to a racially discriminatory policy.”10 The school board promised to study the issue but refused to adopt a policy regarding school desegregation or make any substantive policy changes.11

Civil rights activists continued to press their case in the early 1960s through community organizing, lawsuits, and public protests. “The NAACP is recruiting allies all over the city . . . in its war against the Chicago Board of Education,” the Chicago Defender reported in April 1961. Parents from Southside neighborhoods Chatham, Park Manor, and West Avalon gathered for a mass meeting where they heard NAACP executive secretary Reverend Carl Fuqua urge the parents to organize to demand that the school board address school segregation.12 “As long as Superintendent Benjamin Willis and the board of education take the attitude of ignoring any positive action to integrate Chicago public schools,” Fuqua told the parents, “they are assuming the roles of ‘protectors of a segregated system’ in Chicago. They are in fact acting as segregationists whether they are or not.”13 One outcome of this community organizing was “Operation Transfer,” a plan where 160 black parents went to eleven white schools with open seats to request that their children be transferred.14 The parents were refused, as they expected, but they demonstrated black parents’ increasingly public frustration with school conditions.

In September 1961, days after “Operation Transfer,” a group of black parents sued the Chicago Board of Education. Paul Zuber, who had represented the New York parents in the Skipwith case, also represented the Chicago parents in Webb v. Board of Education of the City of Chicago. Fresh off a victory in Taylor v. Board of Education, New Rochelle, where the court found that the school board had gerrymandered school boundaries to maintain segregated schools, Zuber was optimistic about the Chicago case. “You’ve got a segregated school system,” he told parents at an overflowing community meeting. “It is planned and perpetuated by your Board of Education, it is administered by your superintendent of schools. What are you waiting for?”15 The parents in the Webb case asked the court to enjoin the school board from assigning black students to overcrowded schools, to assign black students in overcrowded schools to white schools with open space, and to declare the “neighborhood school” policy illegal and unconstitutional.16 School officials adamantly denied the parents’ charges. In his affidavit in the Webb case, Superintendent Willis blamed overcrowding on black migration into Chicago and argued, “I know of no attendance area that has been gerrymandered, no construction site that has been selected, no double or overlapping shift program that has been instituted, no classrooms that have been allowed to remain vacant, no upper grade center, elementary or high school branch that has been established for the purpose of creating or maintaining ‘Negro elementary schools’ or ‘white elementary schools’ in Chicago, as charged by the plaintiffs’ affidavit.”17 Federal district judge Julius Hoffman dismissed the Webb case in July 1962 because the parents had not exhausted Illinois’s state administrative procedures before going to federal court. The Webb case was later reopened and settled out of court in August 1963 with an agreement that the board would adopt a policy of integration and that an independent panel, chaired by University of Chicago sociologist Philip Hauser, would examine the school situation.18

With legal options uncertain and unpromising, civil rights activists and parents employed a range of protest tactics. A group of black mothers with the Woodlawn Organization, a Saul Alinsky community organization that favored direct action protests, staged uninvited visits to white schools to search for empty classrooms. Four of the “truth squad” mothers, as the Defender called them, were arrested and charged with trespassing and disorderly conduct.19 Another group of parents staged a two-week-long “study-in,” with parents and volunteer tutors teaching students in school hallways and basements, to protest a transfer order that sent students from the overcrowded Burnside Elementary School to another black school rather than a nearby white school. Outside the school, black and white parents and ministers carried signs reading “Schools Factually Segregated” and “No Double Shifts,” and twenty-six demonstrators were arrested for trespassing and unlawful assembly.20 “The situation calls for a showdown,” the Defender editorialized. “The community cannot continue to have its rights brazenly flaunted [sic] by irresponsible school officials. The battle line must be drawn somewhere in the struggle to democratize the Chicago schools; Burnside is just as good a place to start the fight.”21 Leading the school battle was the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations (CCCO), formed in spring 1962 as a civil rights coalition including the NAACP, the Urban League, Teachers for Integrated Schools, the Woodlawn Organization, CORE, Chatham-Avalon Park Community Council, and Englewood Council for Community Action.22

Parents and activists directed much of their anger at Superintendent Benjamin Willis. In addition to condemning Willis’s refusal to acknowledge or address school segregation, civil rights advocates were upset with Willis’s policy decisions regarding school overcrowding. Willis ordered the purchase of over one hundred mobile classrooms, called “Willis Wagons” by his detractors, to relieve overcrowding at black schools without transporting black students to white schools with open seats.23 While school officials contended that mobile classrooms addressed the black communities’ complaints about overcrowding, the Defender saw the policy as the last straw for black Chicagoans: “It is bad enough to deny us membership on the Mayor’s School Board Nominating Committee; it is frustrating enough to prevent us from having a responsible spokesman on the Board. On the top of all this come . . . mobile classrooms, aptly dubbed Willis Wagons, to cram down our throats Mr. Willis’ segregative school policy. . . . On the eighth anniversary of [Brown v. Board], Chicago is witnessing a display of defiance of the Court’s order undreamed of even in Alabama and Georgia.”24 Fed up with Willis’s resistance, civil rights advocates called for the superintendent to be fired. CORE circulated petitions across the city calling for Willis’s resignation. “Dr. Willis yields immediately to the protest of white parents, while the complaints of dozens of Negro groups . . . go without any comment from the superintendent,” Chicago CORE chairmen Milton Davis said.25 The Defender dedicated their front page on August 15, 1963, to a series of accusations about Willis. “We accuse him of gerrymandering school districts for the primary purpose of ‘containing’ Negro children in predominantly Negro schools. . . . He is an emblem of racial segregation. Dr. Willis must go.”26 Protestors picketed outside Willis’s Lakeshore Drive apartment, carrying signs reading “Willis-Wallace, What’s the Difference?”—comparing Chicago’s superintendent to Alabama’s segregationist governor George Wallace—and “Whitson Votes Good Like a Segregationist Should,” referring to school board member Frank Whitson.27 Chicagoans at the March on Washington in August 1963 chanted “Down with Willis.”28

FIGURE 7. The Chicago Defender accused Superintendent Benjamin Willis of segregating Chicago’s schools. Willis became the focal point of the black community’s protests against educational inequality in the city. Chicago Defender, August 15, 1963.

While Willis drew the ire of civil rights advocates, his resistance to school desegregation garnered support from many white parents, business leaders, and the Chicago Tribune. Parents of students at all-white Bogan High School, for example, protested the transfer of a small number of gifted black and white students in September 1963. The students, who were eligible to change schools under a new policy that allowed high-school students in the top 5 percent of their class to transfer to schools with honors courses. Twenty-five hundred white parents and community members protested the planned transfer, carrying signs reading, “We Support Dr. Willis and Neighborhood Schools.”29 White students chanted, “Two! Four! Six! Eight!—We don’t want to integrate!”30 A delegation of Bogan parents met with Willis and found him receptive to their concerns, as did white parents who objected to Austin High School and Washington High School being on the transfer list. Without consulting the school board, Willis removed over twenty schools from the transfer list (including Bogan, Austin, and Washington), leaving only nine schools where academically talented students could transfer.31 Parents of the gifted Hirsch High School students who had attempted to transfer to Bogan obtained a court order directing Willis to abide by the board’s stated transfer policy. Willis resigned rather than obey the court order, but three days later, the board voted not to accept his resignation and worked to reconcile with Willis.32 The Chicago Tribune found the news of Willis’s resignation “distressing” and wrote, “All things considered he has done an outstandingly good job.”33 Willis also received votes of support from business leaders, including Frederick Bertram, president of the National Home and Property Owners Foundation, who wrote the board of education to praise Willis and condemn civil rights protestors: “On behalf of the great majority of school children, parents, and taxpayers of Chicago, we demand that you seek the reinstatement of Benjamin C. Willis as superintendent. The school board’s abdication to the demands of small pressure groups of disorderly demonstrators is disgraceful. . . . Rule of government by pressure of demonstration is anarchy.”34

As this letter suggests, by 1963 Willis had become a proxy for expressing opposition to or support for civil rights and school desegregation. Sociologist Philip Hauser, whom Willis asked to chair the committee evaluating the schools, told Congress that Willis “has become the symbol of segregated schools not only to his detractors, white and Negro but, also, to his supporters. His recent under-the-table reappointment was heralded by many as a great victory for white supremacy. His refusal to integrate the schools and his silence on the subject . . . [have] made him the champion of racists in Chicago as well as the devil of the civil rights movement.”35 White parents, community leaders, and media who valued Willis’s resistance to school desegregation inevitably outweighed whatever pressure civil rights activists were able to apply.

The board’s peaceful reconciliation with Willis, combined with years of frustration over overcrowding, temporary teachers, and inadequate resources at schools attended by black children, led CCCO to organize a massive “Freedom Day” school boycott. Similar to school boycotts in cities like Boston, Cleveland, Milwaukee, New York, and Seattle, the Chicago boycott was designed to force the school board to take action to address school segregation.36 Led by Lawrence Landry, a Chicago native with two degrees from the University of Chicago, the CCCO published a list of thirteen demands in advance of the boycott.37 The list included demands that the school board remove Willis as superintendent; publish an inventory of school population, classroom availability, and racial demographics for students and teachers in each school; and fully use all available space before using mobile classroom units.38 Over 220,000 students (47 percent of total enrollment) stayed away from public schools on October 22, 1963, with many attending Freedom Schools at churches and community centers.39 Ten thousand people marched around city hall and the board of education building, including students carrying signs reading “Willis Must Go” and “No More Little Black Sambo Read in Class.”40 Boycott leaders said the boycott exceeded expectations and threatened to hold one-day boycotts every month until their demands were met. The Defender’s headline sprawled over half of the front page: “Boycott a Thumping Success! 225,000 Kids Make Willis Eat Jim Crow.”41 The Chicago Tribune saw the boycott in a different light. “No government can permit such a reign of chaos,” the Tribune editorial page read. “Chicagoans as a whole have been patient with the civil rights demonstrations and generally sympathetic with the aims of Negroes to achieve equality of opportunity. Much of the public’s patience vanished Tuesday when the reckless men at the head of the civil rights movement ordered thousands of children out of the public schools. The patience that remains will disappear if the tactics of obstructing government and business are continued.”42

A second school boycott on February 25, 1964, further revealed the gulf between civil rights advocates and the city’s white officials. The Defender declared Freedom Day II a success, with 175,000 students staying out of school.43 The February boycott and protest march around city hall was also designed to impress on Mayor Daley and other politicians that they could not sit on the sidelines of the school fight. Alderman Charles Chew, the only black alderman who supported the boycott, said, “The Democratic machine is no longer oiled.” “It is clear that we won today,” Lawrence Landry declared regarding the boycott and protest march. “We walked thru the City Hall this time. Next time we will walk over it.”44 Mayor Daley was unimpressed with the boycotts. “What do they prove?” he asked. “Education should never be a political issue and it should never be used by either party to take advantage in politics.”45

Schools officials linked their opposition to the boycotts and civil rights demands to concerns about “busing.” Speaking days before the second school boycott, school board president Clair Roddewig said he strongly opposed “busing kids all over town to integrate schools.” Roddewig saw civil rights demands as triggering a dismal chain of events. “First, civil rights leaders demand that Negroes be bused out of all-Negro districts to all-white schools,” he said. “Then, as during the recent New York boycott, they demand that white students be bused to all-Negro schools that still remain in the Negro residential districts. Next, when white parents begin sending their children to private schools, they will demand that parents be told where to send their children to school. When in America the day arrives that the state assigns all children to schools, we are finished.”46 For Roddewig, as for many of his peers in other cities, this dire forecast justified school officials’ opposition to school desegregation. Framing this as a resistance to “busing” rather than resistance to school desegregation was more than simply a choice of words. Describing civil rights leaders as asking that “Negroes be bused out of all-Negro districts to all-white schools” focused attention on “busing” rather than on the educational rights black students were denied in the “all-Negro districts” perpetuated by school officials. Roddewig’s fear that “the state” might someday assign all children to schools overlooked the role school boards, as state agencies, already played in assigning children, and presented school officials as innocent bystanders to questions about school zoning and assignment. Finally, presenting civil rights demands as the trigger for this grim educational future made the movement seem unreasonable and ultimately un-American.

FIVE DAYS IN CHICAGO

By 1965, Chicago’s civil rights advocates had engaged in nearly a decade of organized efforts to uproot school segregation but saw little movement from school officials. A series of external reports—Northwestern University law professor John Coons studied the schools for the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in 1962, and University of Chicago professors Philip Hauser and Robert Havinghurst led committees that published reports in 1964—corroborated and extended the research on school segregation in Chicago that civil rights groups had been conducting since the mid-1950s.47 Neither these reports nor the school boycotts were enough to force Willis and the school board to take action on school desegregation. Meyer Weinberg, chairman of the CCCO’s Education Committee and editor of the journal Integrated Education, expressed frustration at how school officials offered only watered-down proposals in response to civil rights demands. “The civil rights movement always loses because we let Willis define the problem and make the proposals—to which we only react,” Weinberg told his colleagues. School officials would face more pressure, he suggested, if the schools were confronted with the loss of federal funds due to violations of the Civil Rights Act.48 To this end, on July 4, 1965, the CCCO filed a complaint with the U.S. Office of Education charging that the Chicago Board of Education had violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

FIGURE 8. Flyer for Freedom Day school boycott sponsored by the Coordinating Council of Community Organization. Over 220,000 students stayed out of school to protest school segregation and educational inequality in Chicago. Civil rights activists organized similar school boycotts in cities like Boston, Cleveland, Milwaukee, New York, and Seattle on October 22, 1963. Chicago Urban League Records, University of Illinois at Chicago Library, Special Collections.

FIGURE 9. Thousands of Chicagoans marched in support of the Freedom Day school boycott, October 22, 1963. Film still used with permission of Kartemquin Films.

Chicago presented the first test of Title VI in schools outside the South. Title VI had received relatively little attention in the lengthy debates over the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but quickly emerged as one of the most important and controversial aspects of the legislation. In requiring compliance with antidiscrimination provisions to receive federal funds, Title VI gave the federal government a new weapon to compel school districts to end school segregation.49 And as federal funds came to constitute a larger share of local school budgets, the threat of withholding significant sums of money added a material cost to resisting school desegregation. In Chicago, for example, federal aid to schools had increased from $372,000 in 1954 to $47.5 million in 1966.50 Like Title IV, however, which differentiated between southern school segregation and northern “racial imbalance,” Congress did not intend Title VI to apply outside the South. In the floor debate of the Civil Rights Act, Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota reassured Senator Robert Byrd of West Virginia that “there is no case in which the thrust of the statute under which the money would be given would be directed toward restoring or bringing about a racial balance in the schools.”51 Humphrey also referenced Bell v. School City of Gary, Indiana, a 1963 federal court decision upholding “neighborhood schools,” arguing, “This case makes it quite clear that while the Constitution prohibits segregation, it does not require integration.”52 After receiving the CCCO’s complaint regarding Chicago, James Quigley, HEW assistant secretary, said the agency was trying to figure out the applicability of Title VI outside of the South. “I’m inclined to feel that title VI does not apply to complaints of de facto segregation, but might be applicable to some conditions in the north,” Quigley said. “If we find that Negro children are in fact being treated differently from white children in Chicago, for example, title VI would give us the power to act.”53

While federal officials were weighing their options in Chicago, the Tribune railed against the threat of withholding federal funds from the city’s schools. Describing the CCCO’s complaint as “the latest example of extremism in this movement,” the Tribune predicted, “If the government should be silly enough to mount an offensive against Chicagoans by withholding money it has wrung out of them in taxes, the resentment predictably would be great and general.” In language that drew on anti–civil rights propaganda funded by far-right conservatives and the state of Mississippi, the Tribune’s editorial saw Title VI as “a hundred billion dollar blackjack . . . with which to club the American people into submission.”54

School officials shared this anger and provided little assistance to the federal investigators. John Coons, who studied Chicago’s schools in 1962 for U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, ran into administrative resistance while preparing a report for HEW regarding Chicago’s compliance with the Civil Rights Act. Coons recalled having the sense that school officials and principals “were uneasy in their chairs when you talked to them.”55 Over the course of a three-month survey, Coons was granted only a ten-minute meeting with Superintendent Willis, which, Coons remarked, “consisted of a denunciation of my mission and myself.”56 Coons described Willis’s “refusal to cooperate” as “final and total” and wrote to school board member Frank Whitson in an attempt to find someone from the schools to provide information to balance the civil rights complaints. “This situation would have some aspects of comedy were it not for my responsibility to report to the Federal Government,” Coons said.57 New York congressman Adam Clayton Powell told Francis Keppel, who oversaw HEW educational policy as U.S. commissioner of education, that Willis’s lack of cooperation “would seem to me to constitute open defiance of the requirements of the civil rights act of 1964.”58 To put more pressure on Chicago, Powell arranged hearings as chair of the House Education and Labor Committee to investigate “de facto racial segregation” in Chicago’s schools.

On September 30, 1965, Keppel wrote to Illinois superintendent of public instruction Ray Page indicating that Chicago’s schools were in “probable noncompliance” with the Civil Rights Act and that the city’s application for $30 million as part of Elementary and Secondary Education Act would be deferred under Title VI. Al Raby, a Chicago native and former teacher who emerged as CCCO’s leader, called the decision “the first crack in school segregation in Chicago.”59 The Defender saw HEW’s decision as a vindication of the black community and years of school segregation complaints: “Keppel’s action freezing $30 million dollars in Federal aid for Chicago public schools establishes beyond the shadow of a doubt that the charges of de facto segregation were not figments of psychotic imagination.”60

News of the federal fund withholding also topped the front page of the Tribune (“City School Aid Halted”), and the paper’s coverage anticipated how HEW’s intervention in Chicago would play out over the next week.61 The Tribune quoted U.S. congressman Roman Pucinski, who represented a heavily Polish-American northwest Chicago district, calling the decision “arbitrary, capricious, unjustified, and a violation of the civil rights act itself.”62 Congressmen Daniel Rostenkowski and John Klucsynski also spoke out against HEW, as did Senator Everett Dirksen, who, as Senate minority leader, had helped craft the Civil Rights Act and its focus on enforcement in the South.63 The Tribune’s editors phrased their opposition to HEW as an open challenge to the state’s leading politicians: “How humiliating it must be for Mayor Daley and Gov. Kerner, the leading Democrats of Illinois, to be kicked in the teeth by a petty burocrat [sic] of the Johnson Democratic administration! . . . The Tribune warned that [the Civil Rights Act] would become a dangerous new stick in federal hands. The stick is now being used to beat Chicago.”64

Daley did not need the Tribune’s editorial to convince him to fight to get the $30 million in federal funds restored to Chicago’s schools. As mayor of Chicago and head of the Cook County Democratic organization, Daley was one of the most powerful and influential politicians in the country. At the local level, he had control of tens of thousands of city and county jobs; at the national level, Daley could deliver votes to Democratic presidential candidates and support from Chicago congressmen for presidential legislative priorities.65 Daley had the ear of President Johnson, and when both men were in New York on October 3 for an immigration bill signing, he told the president about his anger and confusion over the funds withholding.66 The next day at the White House, President Johnson conveyed Daley’s anger to Keppel and made it clear that he wanted HEW to settle the issue as quickly as possible.67 Ruby Martin, who later directed HEW’s Office of Civil Rights, speculated that the first lady’s efforts to bring more flowers to U.S. cities and highways figured in the president’s decision. “There are some people who suspect that Lady Bird’s Beautification Program was at stake,” Martin recalled in a 1969 interview, “and that Mayor Daley controls eleven votes in Congress, and he threatened to pull all eleven of them back to Chicago or off the floor when Lady Bird’s Beautification Bill came up.”68 On October 5, HEW undersecretary Wilbur Cohen flew to Chicago to negotiate a settlement with school board president Frank Whitson. Under the terms of the agreement, HEW released the funds and withdrew its investigators until the end of the year. In exchange, the school board only had to agree to investigate school attendance boundaries and reaffirm two policies regarding trade schools and apprenticeship programs.69

HEW’s abrupt surrender in Chicago reverberated locally and nationally. “We are shocked at the shameless display of naked policy power exhibited by Mayor Daley,” CCCO’s Al Raby said. “Not a single segregated situation will be substantially altered by the terms of the agreement reached between HEW and Whitson. We are still saddled with the Willis system of separate, inferior education. A school board committee has been appointed to investigate school district gerrymandering. For the same school board which created the gerrymandering to investigate its own handiwork is absurd.”70 For others, securing the status quo in Chicago’s schools was a positive outcome. Representative Pucinski, who also lobbied the White House to persuade HEW to restore the funds, described the decision as “an abject surrender by Keppel—a great victory for local government, a great victory for Chicago.”71 The negotiated settlement involved only “minor concessions,” Pucinski said, “face-savers for the Office of Education. They don’t mean a thing.”72 The Tribune called Willis “a man among midgets” and praised him as the “only official who has had the courage to stand up against the power play of the federal office of education.”73 Writing in the Washington Post, columnists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak said that after the “fiasco” in Chicago, “Willis is more than ever a white folk hero and will be harder than ever to get rid of.”74 The New York Times saw the Chicago fund case as “a singular instance of a northern city’s cry of ‘states rights’—more precisely, ‘city’s rights’—to defeat a Johnson Administration strategy.”75 For Adam Clayton Powell, Chicago “represented the first abject surrender to the principle that separate but equal is wrong in the South, but acceptable in the North—particularly if a city can muster enough Northern politicians and educators with a segregationist mentality to practice this shameful hypocrisy.”76

For HEW, Chicago ended discussions of using Title VI to eliminate “de facto” segregation and significantly limited federal investigations of school segregation outside the South.77 Keppel met with school officials from the fifty largest cities at the end of October 1965 to calm their fears about federal intervention in large cities.78 “It is obvious that the question of civil rights in the big cities won’t be answered to my satisfaction or that of people in my position, for years,” Keppel remarked.79 A January 1966 HEW memo to the White House outlined the logic for focusing on de jure segregation in the South:

The primary reason for taking this approach is our lack of factual information about the various issues, situations, possibilities and probabilities in the North and West. We have had almost a year and a half of dealing with the South, but we have only been concerned with the North and West for about four or five months. The general consensus is that we should be more knowledgeable before we issue standards which we may live to regret, either because they are too narrow, too broad, or inadequate. The answer to queries about why we are not dealing with the North and West is that, while Title VI applies to the North and West as well as to the South and while we are investigating complaints of discrimination against Northern and Western schools, we simply have not had enough experience as yet in these areas to issue guidelines of general applicability.80

Ruby Martin described Chicago as a “tremendous setback” for HEW. After Chicago, she said, “We made a conscious decision—some people call it a political decision—not to take on any large school districts . . . because our resources are limited. You can get involved in a large city for two years and come out of it bloodied, bruised, and scarred, and nothing [is] going to change the situation.”81 For school officials, politicians, and civil rights advocates in other northern cities who were following the case, the lesson from Chicago was that federal authorities did not have the resources or political will to combat school segregation in the North. HEW’s surrender in Chicago encouraged school officials and politicians to maintain positions of resistance and noncompliance with regard to school desegregation, while it led black parents and students to doubt that any federal authority could successfully address their concerns.

“NO ONE LIKES TO BE PUSHED”

After thirteen years as the controversial superintendent of Chicago’s public schools, Benjamin Willis resigned in 1966. Civil rights advocates greeted Willis’s departure with relief and the hire of the new superintendent, Dr. James Redmond, with cautious optimism. HEW officials hoped that Redmond’s appointment would lead to voluntary compliance on some of the issues raised in the prior year. Harold Howe, who replaced Francis Keppel as commissioner of education, was an old friend of Redmond’s and struck a cautious tone compared with HEW’s initial efforts in Chicago. After ensuring that “Mayor Daley approves of our plans,” Howe sent Redmond a report that, he wrote, “outlines serious conditions in the Chicago schools which, in our view, may involve violations of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act. We believe that the constructive way to proceed is to seek your cooperation in moving rapidly to correct the conditions outlined in the report.”82 While this approach lacked any threat of withholding federal funds, Redmond was far more receptive than Willis to drafting a plan to increase school integration.

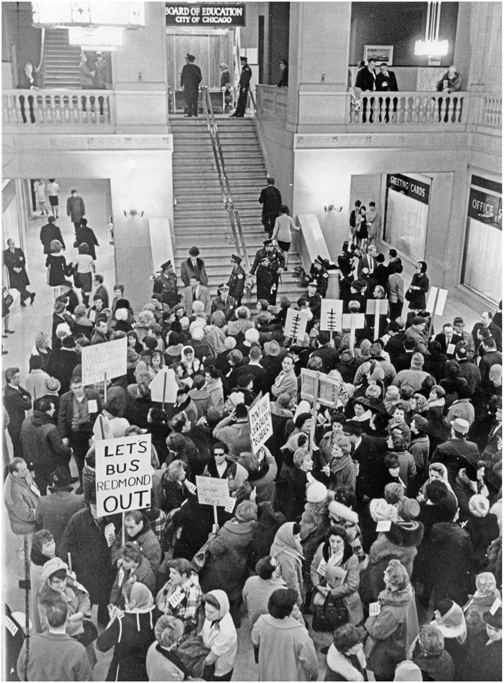

When Redmond submitted his report, “Increasing Desegregation of Faculties, Students, and Vocational Education Programs,” to the board of education in late August 1967, it was quickly attacked as a “busing” plan. Days after the plan was made public, white parents from southwest- and northwest-side community groups slowed traffic with a hundred-car motorcade. The cars carried signs reading “Stop School Bussing” and “Does Supt. Redmond Teach Education or Integration?” and many contained children holding railroad flares out of open windows.83 State senator Joseph Krasowski, who represented the white southwest side, criticized “busing” as an “ivory tower plan” that would “hinder good education.” “I don’t oppose school integration,” he argued, “but the school board shouldn’t stress integration more than education. . . . You can’t foist this upon the people. No one likes to be pushed, and when they are they’ll push back.”84

These “busing” protests continued into 1968 as the school board considered implementing Redmond’s proposals. Hundreds of white parents, many wearing buttons reading “Willis for Superintendent,” pressed into a board of education meeting room with the goal of “getting our faces on camera for a change,” as one demonstrator said. “Put Redmond on a Bus—Leave the Driving to Us,” read one sign.85 White parents staged another motorcade in January 1968, with signs reading, “Stop Integrating, Start Educating,” “Down with Busing,” and “Redmond, Resign Right Now.” “I’m 100 per cent against busing,” Harry Kuhr, chairman of the Taxpayers Council of the Northwest Side, told the Tribune. “Regardless of what kind of teachers you give these people, they are not going to learn.”86 As this reference to black students as unteachable suggests, antiblack racism fueled these “busing” protests. “The proposed busing of Negro students from crowded Austin area elementary schools to Northwest Side schools has aroused racism to white heat,” the Defender editorialized.87

FIGURE 10. White demonstrators gather at the Chicago Board of Education to protest superintendent Dr. James Redmond’s “busing” plan. Associated Press photo, January 1968.

FIGURE 11. White parents protest Chicago superintendent Dr. James Redmond’s plan to begin school desegregation. This mother’s button reads, “Reading, Rittin, Racism. Out with Bus Plan.” ABC News, January 10, 1968.

Unedited ABC news footage of the protests shows white demonstrators struggling to articulate their opposition to school desegregation and their defense of “neighborhood schools” without explicitly expressing racist sentiments. “We picked our neighborhood for schools, for shopping,” a mother explained to ABC’s reporter. “Why should they take my five or six year old child and bus it eight miles way, when I’ve got a school a block away. It don’t make sense. You’re taking the rights away from the Americans. This is the only right we have left to fight for, our children.” The next woman to speak expanded on this sentiment: “They got everything. What, Abraham Lincoln gave them freedom, so they want all of Chicago, ’cause it’s Illinois? I have nothing against them, but they should stay in their own schools. . . . Let them stay where they belong.” When another mother added, “Let them stay in their own territory,” her fellow protestors redirected her: “No, no, bad answer.” She reframed her remarks: “When I wanted to transfer my children to the school of my choosing, they told me, it’s out of the district. So why are they coming to the district I moved to? Why don’t they stay in their own district?” The protestors were sometimes less careful with their wording. When the ABC reporter asked a protestor, “Is this a matter of Negroes coming into your school?” she replied, “No, because I went to school with niggers, there was nothing wrong with it.”88

These interviews are interesting because they make clear the logic that underscored the argument for “neighborhood schools.” These white mothers understood that Chicago was among the most segregated cities in America and that so long as school district lines tracked with neighborhood boundaries, their schools would be untouched by racial integration. In 1966, just two years before these “antibusing” demonstrations, Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference partnered with local civil rights activists to lead marches in Chicago to call attention to housing segregation and rally support for federal open-housing legislation. White neighborhoods in Chicago and the neighboring working-class suburb of Cicero responded with mob violence. King, who was hit with a rock thrown by one of the four thousand white southwest-side residents who blocked the marchers, told reporters he had “never seen as much hatred and hostility on the part of so many people.”89 If white “antibusing” activists had intimate knowledge of how segregation in Chicago was maintained, they also understood that in public contexts they were best served by framing their defense of white neighborhoods and schools in language that was not explicitly racist. They therefore emphasized “freedom of choice” and “neighborhood schools” to make their case that they had a right to white schools.

Like Parents and Taxpayers in New York, these Chicago demonstrators also argued that they had a right as taxpayers to avoid school desegregation. “We’re middle-class working people,” one mother stated. “We own homes, they’re not big homes. . . . We pay $500 in taxes a year.” Another white mother argued, “We are here because the Board of Education is our city’s spokesman for what we want. . . . We expect the Board of Education not to determine what they’re doing in the city of Chicago by what HEW or the federal government tells them to do. We are paying taxes, the tax money comes back to us. We should determine what our tax money is and is not used for.”90 Without explicitly referencing race, these protestors argued that white taxpayers were more important citizens and more worthy of the school board’s attention than black Chicagoans/taxpayers.

As in New York, opposition to “busing” emerged in Chicago on a much larger scale than the proposed use of buses in school desegregation plans. And as in New York, “antibusing” protests persuaded school officials to curtail what were already modest plans. In December 1967, Redmond proposed a plan to bus five thousand black and white students between the South Shore and Austin areas.91 After white protests, this two-way plan was discarded in favor of a one-way plan involving just over one thousand black students. State senator Richard Newhouse noted the disproportionate attention “busing” received relative to the number of students set to be bused for school desegregation: “The great cloud of smoke rising from the school busing proposal has obscured the fire of the real issue. School busing is a supposed answer to federal charges that Chicago operates segregated and unequal schools. But the plan for busing—despite the furious debate over it—applies to only 1,035 children, fewer than one per cent of the black children in the city’s schools.”92 Congressman Roman Pucinski interpreted these numbers differently. “Mr. Redmond’s plan initially calls for busing only 1,035 pupils, but it says in his report that 75 per cent of the pupils in the city’s schools may be bused in the not too distant future,” Pucinski told a crowd of eight hundred people gathered at an “antibusing” meeting at Norwood Park Elementary School. “That means busing 450,000 children.”93

Fears about “busing” continued to develop at a series of rallies and meetings with school officials in early 1968. The school board took the desires of white “antibusing” parents into account in rejecting Redmond’s plan to bus 1,035 black students to white schools.94 The Defender saw the failure of the plan as yet another example of how school officials prioritized white parents’ demands: “By capitulating to a howling mob of racists and political mountebanks, the Chicago Board of Education shows that it has neither the courage of its convictions nor a sense of the direction in which the public schools should go. Negro parents here are choking with bitter resentment over the Chicago Board of Education’s indefensible resolution. Even the Little Rock Board of Education had more gumption.”95

The “busing” plan that the school board eventually implemented, in March 1968, called for one-way “busing” of only 573 black students. Of these eligible students, only 249 participated on the first day.96 Redmond said he could understand why black parents in the west-side Austin neighborhood, who had lobbied to have students bused out of overcrowded schools, would have soured on the plan. “How would I feel—how would anyone feel—after all the weeks of oratory and threats?” Redmond said. “I am encouraged that there are this many.”97 With police escorts, the buses carried black students to eight white elementary schools, where the young students encountered reminders that to many in the neighborhood they were unwelcome. “They can’t get into our neighborhoods, so they are trying to ruin them for us,” one heckler shouted. Another yelled, “They ran me out of two neighborhoods already, and I’m not going to let them run me out of here.”98 At another school, two white mothers were arrested for throwing eggs at buses carrying black students.99 ABC News underscored these sentiments by emphasizing that “busing” was a story about white parents and white neighborhoods. “These people behind me are white parents,” ABC’s reporter said, “and today for the first time their white children are going to school with Negro children. Many of the people feel that what they witnessed today is the start of what they are sure will be the destruction of their neighborhoods.”100 Still, the Defender described the start of “busing” for school desegregation as a “smooth beginning.” One of the black mothers who stood outside the new school to encourage and protect the arriving black students expressed resolve in the face of resistance. “The first day my child came home crying,” she said. “The second day it wasn’t so bad at all.”101

• • •

“How long should it take an obvious truth to become a bona fide, recognized, undeniable fact?” Black journalist Vernon Jarrett raised this question in 1979 in response to a new HEW statement on Chicago’s schools. Drawing on school board meeting minutes and including over one hundred pages of supporting evidence, the statement charged that since 1938 Chicago’s school board had “created, maintained, and exacerbated . . . unlawfully segregated schools systemwide.”102 This charge of intentional segregation validated the complaints made by civil rights advocates over the previous twenty years. The 1979 HEW statement again faced a resistant school board and lack of federal support, especially after the Reagan administration reorganized HEW into Human Services and shifted what little civil rights enforcement there was to the Justice Department. In 1983, U.S. district judge Milton Shadur approved a consent decree between the Chicago school board and the Justice Department that called for majority-white schools to have at least 30 percent minority enrollment and for increased use of magnet schools to encourage voluntary integration, but did little to improve educational opportunities at the city’s remaining all-black or majority-minority schools.103

Chicago stands out in the history of “busing” for school desegregation as the paramount example of the inability of federal authorities to uproot school segregation outside the South. Despite overwhelming evidence that Chicago school officials were not innocent bystanders to the creation and maintenance of racially differentiated schools, the federal government lacked the political will and resources to require school desegregation in the city. Civil rights activists, parents, and students were organized, creative, and persistent in their protests, but Benjamin Willis and Mayor Daley, a recalcitrant school leader and a powerful political boss, ultimately thwarted their efforts. Willis, as founder and president of the Research Council for the Great Cities Program for School Improvement, which brought together the leaders of the fourteen largest city public school systems, was the nation’s most influential school superintendent in this era.104 His near absolute resistance to civil rights, in the face of public protests and federal investigations, surely influenced what school officials in cities like Cleveland, Detroit, Los Angeles, and San Francisco felt was necessary or required to satisfy federal civil rights standards.

Boston school officials were among those who took notice of HEW’s retreat in Chicago. Two days after HEW withheld funds from Chicago, and before Mayor Daley successfully pressed for them to be restored, the Boston Globe published an article titled “And Boston Begins to Sweat.” “As a stunned Chicago learned it may lose $34 million in Federal school funds,” the article began, “a government team continued to investigate possible discriminatory practices in Hub schools.”105 After getting drummed out of Chicago, the federal investigators trod very lightly in Boston, allowing “antibusing” resistance to school desegregation to expand and flourish in the Cradle of Liberty.