The Executive Committee of the Communist International turned its attention to Australia early in 1926 as the full extent of the problems there became apparent. News of Baracchi’s defection, along with the reports of the scheme for a breakaway Labor Party, were probably the cues for its request that the Australians send a representative to Moscow.1 Hector Ross arrived in April bearing a lengthy report and was subjected to close interrogation, not only about the fortunes of the united front and the organisation of the Australian party, but also about the circumstances of his country, its economy, demography and national traditions. Ross was certainly disconcerted by the extent of the discussion. ‘What is the position of the natives of Australia and the natives of New Zealand?’ he was asked. ‘The Australian natives are not to be reckoned with at all’, he replied. None of the members of the Anglo–American Bureau—Comrades Pepper (Pogany, the Comintern representative in the United States), Ercoli (Togliatti, the Italian leader), Rajani Palme Dutt (the Indian–Scandinavian theorist of the British party), Hugo Rathbone (his henchman) and Manabendra Nath Roy (the outstanding Indian revolutionary)—had any prior experience of Australia. They based their conclusions on the testimony of the Australians, partly volunteered and partly solicited, onto which they directed the requirements of the Comintern. It was a process that clearly lent itself to mutual misunderstanding, yet it was a genuine dialogue and Ross was fully involved in the final formulation. The result was the first comprehensive statement of how the Communist International apprehended Australian circumstances, and as such is worth examining at length.

The Australia the Comintern described was a vast, sparsely populated continent ‘covered with large-scale cattle and sheep ranches’. While ‘small peasant strata are almost entirely lacking’, the ‘semi-agricultural and semi-industrial workers’ (which was how the Comintern designated shearers with smallholdings) constituted ‘one of the most important elements among the toilers’. Most of the population was concentrated in ‘five or six towns’. The Australian trade unions were exceptionally strong, the level of prosperity high and Australia was the first country to have elected a labour government. Partly because of such ‘conditions’ and partly as a result of conscious effort by the national bourgeoisie and reformist labour leaders, the Australian proletariat was ‘almost completely shut off from the proletariat of other continents’. Isolation maintained the grip of the ‘petty-bourgeois minded, craft-narrowed elements’ who dominated the Labor Party. ‘The slogan of a ‘‘White Australia’’ serves as the rallying cry of all reactionary elements in the labour movement, who are steeped in nationalist ideology, and who seek to isolate themselves in aristocratic arrogance away from the coloured workers and in general from foreign proletarians.’ Under these circumstances the Communist Party of Australia had to wage a desperate struggle for its very existence. Its strength lay in the unions and ‘grim patience in trade union detail work is one of the most important virtues of the Australian Communists’; but they should not forego their right to belong to the Labor Party simply because its treacherous leaders had expelled them from it. Their tasks were therefore to redouble their efforts to provide a militant lead to workers, to combat reformism and British imperialism, to campaign against the ideology of White Australia and to get a foothold among the foreign-speaking immigrants. ‘The Communist Party of Australia can and will become a Communist Party in the true sense of the word when it learns how to combine the fight for everyday demands of the workers with the combatting of the craft spirit of the labour aristocracy, of the ideology of the ‘‘White Australia’’, and of British imperialism.’2

This ‘Resolution on the Australian Question’ was tabled, discussed and adopted by the Australian party at its annual conference in December 1926. The emphasis on the need to shake off complacent insularity and combat both imperial deference and xenophobic nationalism went largely unremarked: the party agreed to campaign against the forthcoming royal visit of the Duke of York and expose the ‘dangerous futility’ of a White Australia, but its decision to prepare a pamphlet on immigration had still to be implemented a year later. Argument centred on the Comintern’s rebuke of the Australian party for neglecting work in the Labor Party. Some delegates wanted a renewed effort for affiliation, others regarded that course as a dangerous diversion of energy. The conference resolved to organise groups of sympathisers inside Labor Party branches, allowing its own members to join these branches only when the executive gave permission and subject to the strict instruction that ‘members must at all times affirm their Communist identity unless instructed to the contrary by the C[entral] E[xecutive]’.3 This final condition, formulated by Kavanagh, was a pointed reminder of Garden’s apostasy just three weeks earlier, but it had wider import. For the conference proceedings revealed different understandings of the Comintern’s instructions and divergent interpretations of how the united front should be applied in Australian circumstances, differences that would widen over the next three years and absorb the party in an increasingly bitter factional conflict. The authority of the Communist International would be invoked for the eventual resolution of the dispute, and the episode is commonly understood as resulting in the Australian party’s final, complete subordination to Moscow, as occurred throughout the communist world during the same period.4

The contours of the process are not in dispute. The Communist International was transformed in the course of the 1920s into an appendage of the Soviet Union, the sharp differences and animated debates of the early congresses yielding to conformity at the infrequent later ones, leaving the executive and its administrative apparatus in sole possession of an enhanced authority. Whereas during the early 1920s there were a number of large communist parties capable of independent action, by the end of the decade the International was severely depleted and thereafter it is impossible to identify any initiative of significance that did not originate in Moscow.5 If the stronger European parties lost their autonomy, the weaker parties of Britain, the United States and Australia were all the more dependent on the support and guidance of the Comintern hierarchy. Until recently the historical literature dealing with these parties was marked by the preoccupations of the Cold War and stressed their supine obedience to a monolithic, totalitarian control; Since the mid-1970s, revisionist social historians have emphasised the interaction of national factors, the force of indigenous considerations of gender and ethnicity, and the variegated nature of lived communist commitment.6

That Australian communists accepted the authority of the Communist International is not in dispute. That Moscow determined the outcome of the factional dispute that wracked their organisation during the late 1920s is a gross oversimplification. Two qualifications can immediately be suggested. First, the Comintern’s formal authority over this distant outpost was belied by dependence upon it for information, and the instructions that Moscow transmitted on the basis of this received information were in turn susceptible to selective interpretation. It was not until the International was able to train a new generation of Australian cadres (a process initiated when the first group of Australians went off to the Lenin School in Moscow at the end of the 1920s) that mutual misunderstandings narrowed. Until then a selective pattern of communication persisted, the Australians telling the Executive Committee of the Communist International what they thought it wanted to hear, and then taking up those passages of the ECCI’s pronouncements that accorded with their own inclinations. The second qualification is a corollary of the first. The local factions appealed to Moscow in their struggle for control of the Australian party, but the issues in dispute were indigenous ones, and are best understood as arising from local circumstances. This can be demonstrated by turning to two specific examples.

The communist group at Lithgow enjoyed particular opportunities to build a united front with the Labor Party. Several of its members were able to attend meetings of the ALP district assembly as representatives of affiliated unions, and they exerted considerable influence on that local body during 1926. In 1927 the eligibility of communist delegates of the Miners’ Federation was challenged and a split developed between Labor sympathisers who supported them and opponents determined to expel them: initially the assembly set aside the rule that required all delegates to sign the pledge of loyalty to the ALP, but subsequently it barred Charlie Nelson and the other communists.7 These party members made no secret of their political identity but others, representing the Federated Ironworkers’ Association, did so for fear of victimisation at the steelworks. The CPA executive gave these party ironworkers permission to operate incognito within the ALP but criticised them for standing for union office without declaring their party membership. The issue was raised at a meeting of the Central Executive Committee in August 1927. Lance Sharkey, a new member of the CEC, led the attack. A lift operator and member of the Miscellaneous Workers’ Union, who had previously tailed behind the Trades Hall Reds, his new militancy indicated a capacity to sniff the winds of change. Sharkey was supported by Hector Ross, just returned from Moscow and fired with zeal, who insisted that ‘this situation arose out of our members functioning in the ALP and is a continuation of the liquidation policy pursued by former members of the Communist Party’. Bill Orr defended his fellow Lithgovians’ need to build up the left in the union before they risked victimisation, and he was supported by Jack Ryan and Esmonde Higgins, who had returned from Western Australia. The meeting endorsed Sharkey’s criticism by nine votes to three.8

Meanwhile a quite different set of circumstances confronted communists in north Queensland. Here the party’s presence was episodic, established initially by Peter Larkin during his 1921 visit, re-established by Norm Jeffery in the following year and revived by him once more in his later tour of 1925. The local communists were mostly footloose workers who had little patience for officialdom and a strong preference for direct industrial action.9 Events in 1925 increased their restlessness. As part of a campaign for a roster system of employment, the local branches of the Waterside Workers’ Federation were refusing to load ships during the end-of-year meat-kill and sugar-crush. The employers encouraged local farmers to descend on Cairns and Bowen with firearms, beat up strikers and drive all known reds out of town, and the Labor government did little to prevent these attacks.10 There was considerable impatience among the unions with the Labor government in Queensland. In 1926 both the railways’ and meatworkers’ unions withdrew their affiliation to the ALP. In 1927 the state government victimised the building unions in a dispute over public works, and then locked out the railway workers for their support of striking sugarmill workers. These were deeply disturbing events for those in a labour movement where class loyalties commanded a deep, instinctive allegiance. Here were Labor politicians and the ALP executive employing the police and the courts against unionists for giving support to fellow workers in their time of need.11

Bert Moxon headed north from Brisbane for a new recruitment drive at this opportune juncture. He found two existing branches—in Cairns and Townsville—each with contingents of militant waterside workers, railwaymen and meatworkers, and formed new ones in the coastal towns of Innisfail, Tully, Lucinda Point and Bowen, along with the sugar townships of Biboohra, Home Hill and Mossman, and the inland mining settlements of Collinsville, Scottsville and Mount Mulligan. Ted Tripp, a young former member of the CPGB who worked as a fitter in the Townsville railway workshop, became secretary of the north Queensland party district. The number of communists enrolled in north Queensland during this period, nearly 200, was far in advance of anything hitherto achieved; their capacity was less certain. Moxon himself reported that the level of political understanding was low, the interest in communist theory even lower: the Communist Manifesto was far ‘too hard’ to use as a textbook in party classes. Relatively few of the recruits were active in their unions, while those who were ‘are proving themselves trade unionist first’. Moxon, who quarrelled with even the most sympathetic union officials, astounded some of these recruits when he told them the party took priority over industrial activity. Patterns of work in the region were seasonal, so it would require a concerted effort to stabilise the groups. Still, the lesson that he brought back from the north was clear: both the ALP and the ‘left wingers’ were worthless, discredited by their actions. The workers were ripe for revolutionary leadership.12

The two examples of Lithgow and north Queensland point in different directions. The one suggests the difficulties local communists encountered as they pursued a united front within the established structure of the labour movement under the vigilant surveillance of the party executive; the other reveals an impatience with the united front and a preference for separatist militancy well beyond the writ of the executive. The two tendencies were not restricted to these places; rather they were manifestations of differences within the Australian party that crystallised during 1926 and 1927 into distinct factions. The executive elected at the 1926 conference was led by Kavanagh. He placed primary emphasis on building a party of industrial militants through close attention to organisation and training. He believed the party had to guard against contamination in its operation of the united front, and accordingly placed strict stipulations on relations with the unions and the ALP. In this approach Kavanagh was supported by Moxon and the Rosses. Higgins and Ryan, on the other hand, wanted to pursue the united front more wholeheartedly in order to foster communist influence in the organised labour movement, while the remaining executive members, Wright, Jeffery and Sharkey, were usually somewhere in between. The differences were apparent in a lengthy debate at the executive’s August 1927 meeting on the continuing battle between Lang and his opponents for control of the New South Wales branch of the Labor Party. Three alternative theses were proposed, by Wright, Hector Ross and Ryan. The one formulated by Wright wanted the party to back Lang and his Labor Council allies against the AWU and right-wing politicians in the hope of winning rule changes that would allow communists to be elected as union delegates to the ALP conference. Ross contended that there was nothing to choose between Lang and his opponents and consequently ‘no working class significance in NSW faction fight’, a slogan originally coined by Kavanagh. Ryan, with support from Higgins and Sharkey, based his proposal on the argument that the workers would only come to see the bankruptcy of Labor and the need to overthrow capitalism if communists encouraged them to make demands upon a Labor government. He therefore wanted the party to organise a communist fraction in the ALP and to press for rule changes that would allow them membership. This in fact was done, but the executive also endorsed Ross and Kavanagh’s uncompromising slogan by nine votes to four.13

Wright was not able to speak to his thesis because he was in Moscow for a further consideration by the Communist International of its Australian section. He said little of the disagreements at home; instead he responded to an assessment of his party’s work that was distinctly more favourable than that given a year earlier. If the 1926 ‘Resolution on the Australian Question’ had read rather like a teacher scolding a backward child, this 1927 resolution acknowledged some encouraging signs of more attentive effort. The resolution was drafted by the Anglo–American Bureau (now chaired by the Russian Petrovsky who had extensive experience in the United States and Britain), then amended by the Political Secretariat of the ECCI, where Bukharin and the Japanese leader Katayama as well as M. N. Roy made substantial contributions. It was accepted that ‘Australian conditions are not indicative of a revolutionary crisis in the near future’—the working class was only beginning to feel its power and it still lacked experience of Labor in office (Wright objected to this historically inaccurate slight on his compatriots). There was spirited discussion of the status of Australia as an outpost of British and American imperialism (it was an independent bourgeois state, insisted Wright). ‘If time is not yet ripe for revolutionary mass action’ in Australia, it was all the more important for the party to persist with revolutionary propaganda and agitation. Work within the unions should be pursued: Australian communists should take their place in the front ranks of the workers in every strike and every struggle. The campaign against ‘social chauvinism’ should be stepped up; communists would insist upon all ‘equality of wages, rights and free admittance to the workers of all countries’ (here Katayama demurred with the prescient observation that ‘I do not think that the Australian workers would approve of this’). Only time would tell whether the Labor Party could be opened to genuine proletarian influence or it would be necessary to found a new party. In the meantime the communists should press their demand for affiliation, not soften in any way their criticisms but rather sharpen them, not fall into the right error of hiding their identity nor the left error of antagonising workers with sectarian revolutionary slogans. To say that ‘the Communist Party must understand how to operate the united front tactic suitably’ was scarcely to clarify Moscow’s expectations.14

Tom Wright brought the Comintern resolution back to the party conference in December 1927 along with a Comintern delegate, R. W. Robson of the CPGB. Robson was clearly unprepared for what he found: an executive split into factions, no preparation for the congress, the congress proceedings consumed in factional conflict. He found the calibre of the leadership ‘very low indeed’, the level of the Australian working class ‘very very low’. He fell out with Kavanagh almost immediately and Kavanagh as conference chairman managed to wrong-foot him by announcing his presence to the delegates on the first day. Since his passport would not bear inspection, he had to give an impromptu address and then beat a speedy retreat.15

Much of the ensuing debate was taken up with recent executive decisions. First, the Lithgow group appealed against the instruction that its members should identify themselves as communists on the grounds that those who were active in the FIA would lose their jobs. Higgins supported them. The Lithgow group was ‘the nearest to achievements in mass work’, he contended, and the executive had ‘greatly failed the Lithgow group in many of its important activities’. Howie, Jack Ryan and Joe Shelley agreed. Kavanagh rejoined that the most important task was to build up the party, not subordinate it to the pursuit of union office or representation on Labor assemblies, and in this respect the record of the Lithgow group was deficient. Nelson and Bill Orr insisted that the group’s main object was to strengthen the industrial movement; Ross replied that their apparent success was gained by stealth. That was too much for Higgins. He observed that two alternative tactics were proposed. The tactic of mass work had brought success in Lithgow, the tactic of separatism employed by Ross during his period at Newcastle had proved utterly fruitless. Lithgow’s supporters had the better of an acrimonious debate, but conference endorsed the position of the executive by 24 votes to 18.16

Next, Norm Jeffery led an attack on the actions of the executive in the New South Wales Labor Party faction fight. By now this issue was well rehearsed. He and a number of other delegates wanted the party to support the industrialists in the hope of winning new ALP rules that would allow communists to represent affiliated unions at Labor Party conferences. The executive, still taking its stand on the slogan that Labor’s factional struggle had ‘no working-class significance’, insisted that the Labor industrialists in unholy alliance with Lang were no better than their parliamentary rivals. The debate was notable for the vehemence of the disputation as well as the new alignments it revealed. Bill Orr contended that the actions of the executive were symptomatic of a more general weakness: ‘The Party was too much concerned with making the working class understand Communist theory instead of getting them to take an active part in the struggle for everyday demands’. Jack Ryan and Esmonde Higgins concurred. Tom Wright took his stand on the Comintern’s recent resolution calling on the Australians to intensify their pressure on the Labor Party. Jack Kavanagh, on the other hand, thought the critics revealed a persistent tendency to submerge the Communist Party into the Labor Party, and the Queensland delegates agreed with him. They carried the conference by 34 votes to seven.17

This argument foreshadowed a further disagreement over the executive’s new thesis on the Labor Party. Presented by Hetty Ross, it was far more pessimistic about the prospects of radicalising the ALP than the Comintern theses of 1926 and 1927. The ALP was ‘purely parliamentary in character’; the possibility that it could be converted into a real workers’ party was ‘extremely remote’; and those communists who took part in Labor assemblies ‘merely serve the purpose of re-attracting dissatisfied workers to the reformist policy of the organisation’. The trade unions, which did not enforce political conformity, were far more propitious sites for communist effort, and activity in the ALP should be restricted to the object of building up the Communist Party. All activity had to be open. There could be no concealment of identity and no participation without direction from the executive. This was far too rigid for Higgins and Ryan. ‘Why cut off one of your arms?’ asked Ryan. Higgins submitted an alternative thesis that diagnosed increased dissatisfaction with the Labor leadership in a period of intensifying class conflict. ‘To this end, the Communist Party must play an active part within the unions and the ALP, seeking in every way, through action as well as propaganda, to increase class consciousness among the rank and file.’ Ross and Kavanagh condemned Higgins’s laxity. Tripp, representing the Townsville group, was adamant that the Labor Party was ‘reformist right throughout’ and communists could not possibly ‘smash reformism’ by submerging themselves in its organisation. The executive’s thesis was adopted by 18 votes to 14.18

Running though each of these debates was a clear division of opinion over the means whereby the Communist Party should operate. For several years the party had pursued a united front, with minimal success and without ever clarifying its rationale. Were the unions and the Labor Party susceptible to radicalisation? Could they be drawn to the left? Or was the united front nothing more than a front, a device behind which communists could infiltrate, recruit new members and discredit their opponents? In practice the Australian party had a bob each way, and the returns on each wager were meagre—communists were debarred from the Labor Party, exerted marginal influence in the unions, and had lost as many members to their prey as they gained from it. Kavanagh’s impatience stemmed from his conviction that the united front diverted Australian communists from the primary task of building a vanguard party of forthright agitators. He did not specifically repudiate the strategy. Rather, he restricted its operation to certain spheres of activity, principally in the unions, though even there he warned that ‘too much attention is paid, in my opinion, to detail [sic] trade union work to the detriment of service to the party’.19 His critics found those restrictions an impediment to their efforts to build communist support. They argued partly from local experience, partly by appeal to the authority of the Communist International and partly out of their conviction that the Australian labour movement was about to undergo a period of tribulation that would provide new opportunities for the united front. On each of these grounds they were in a strong position. Indeed, the record of the conference reveals that the critics spoke more often and more effectively than the supporters of the executive. Yet they lost.

They were defeated not by argument but by numbers. The rules of the party during this period provided for one conference delegate for every ten members, and allowed groups that could not send their own members to nominate proxy delegates. Bert Moxon, basking in the glory of his tour as organiser in northern Queensland, controlled no less than fourteen of these proxy votes at the 1927 conference, which he distributed among his allies there. The proxies were used both to carry the crucial conference resolutions and to control the ballot for the new executive. There were fifteen candidates for eleven positions. Of those elected, Kavanagh, Moxon, Hector and Hetty Ross were solid supporters of the new line, Higgins and Wright were the only critics, while the remainder were uncommitted; among those dumped from the executive were Jack Ryan, Norm Jeffery and Lance Sharkey.20

The factional character of the conference was unprecedented in its intensity, its application to the party organisation wholly new. In clear reference to its divisive effects, Kavanagh closed the conference with an appeal for unity:

There have been heated arguments in expressing our opinions. This does not mean personalities. A difference exists between our conferences and others—there is honesty in all our arguments advanced for the well being of the Party and the working class movement—not of individuals.21

There is no doubt that he was sincere. Kavanagh was pugnacious, dogmatic, egotistical—more than once he was heard to say that he was the only real Leninist in Australia—but he was not vindictive. The allocation of executive duties at the close of the conference attested to the acceptance of differences: Kavanagh was chairman and in charge of trade union work, Wright was secretary, and Higgins in charge of the Agitprop department as well as editor of Workers’ Weekly. Jack Ryan’s wife Edna, who joined the party at this time and ran its Sydney office, has recalled it as a golden age of free debate, with ‘no hushing and stifling, no fear of being accused if one proposed a tactic or an idea’, an ‘open academy’ that ‘developed what was best for individuals and gave them full opportunity to develop’.

‘Am I imagining’, she asked herself 40 years later, ‘that the socialists, the revolutionaries and the communist leadership of the twenties were people of stature? Most of them had intellectual integrity’. The picture she draws is of young, ardent revolutionaries who asked for no quarter in their heated disputation over priorities and methods, but shared an essential respect for each other’s talents and energies. Even the wavering Lance Sharkey, a scruffy, glum, unsociable man who boarded with Higgins and Joy Barrington at Glebe, was included in their fellowship, though recently voted off the executive. The contrast she draws is between this circle of comradeship and Bert Moxon, who represented very different qualities.

The party was somewhat prim and prissy—we must be genuine workers, belonging to a trade union, and to lead as normal a life as possible in order to belong to and be accepted by the working class. Moxon was an urger, a bit of a larrikin living on his wits—he had the reputation of being able to open any lock. We could be tolerant about him but to have him in the leadership was too much.22

This shameless adventurer—Ryan thought him the embodiment of Henry Lawson’s Bastard from the Bush—had begun to take himself very seriously. After his scapegrace conduct in the early Sydney branch in 1922, when he had helped carry the furniture from the Liverpool Street party premises to Sussex Street only to stage a further rebellion there, Moxon had moved to Brisbane and joined forces with J. B. Miles. His colonisation of north Queensland gave him a power base among militants who were contemptuous of their Labor government. His impatience with the sort of patient cultivation of a united front practised in Lithgow coincided with Kavanagh’s mistrust of any tendency to submerge the party’s identity. Even so, their alliance was a temporary one. Kavanagh had little respect for this blustering conman while Moxon, who aspired to Kavanagh’s own position as leader, was already courting friends in Moscow.

The decisions taken by the Australian party at its 1927 conference put it to the left of the Communist International. At that time the Comintern still enjoined the Australians to pursue a united front as the appropriate communist tactic in a period of capitalist restabilisation. As the British representative of the Comintern reminded the conference delegates in Sydney, the intense postwar revolutionary unrest had yielded since the early 1920s to a temporary and partial world stabilisation, and that was the reason for cultivating the unions and reformist parties which still commanded the loyalty of the working class. Yet even as Robson spoke, Stalin was announcing to the Fifteenth Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union that a new third period of capitalist crisis had begun, bringing new revolutionary opportunities and new tasks. His reasons for making this announcement arose partly out of the struggle for control of the CPSU (having defeated the left opposition, he was now turning on the right) and partly from the disastrous failures of the united front in various countries. In Britain, the General Strike of 1926 had collapsed in recrimination between communists and the trade union leadership. In China the communists were butchered in 1927 by the armies of the Nationalists, with whom they had been allied in the war for national independence. Earlier the Italian party had failed to avert fascist dictatorship. By the end of the decade the membership and influence of the Communist International had dwindled close to oblivion.

By the time Stalin codified the doctrine of the Third Period (now capitalised to emphasise its decretal status), the international labour movement had passed through a series of phases since the Great War. First was the period of acute capitalist crisis and revolutionary action culminating in the victory of the Soviet Union over its enemies and the establishment of the Communist International. Then in the early 1920s came a period of partial stabilisation when the labour movement was on the defensive and communist parties pursued a united front. Now, in the Third Period, growing imperial rivalry would intensify conflict both between and within the capitalist countries. Capitalists would seek to suppress workers’ resistance and put down colonial movements of revolt. In the rising conflict of what they characterised as a battle of ‘Class Against Class’, the social democrats would be called upon by the capitalists to impose cuts in living standards and to persuade the workers that they were necessary. In doing so they would be exposed as the worst enemies of the working class, as nothing less than ‘social fascists’. Stalin’s announcement of the Third Period of Class Against Class thus signalled the effective abandonment of the united front.

The turn to the Third Period threw the member parties of the Communist International into disarray. It was not that they clung to the united front—just as the Australian comrades were exasperated by their failure to win over the unions and Labor Party, so the communists of other countries felt increasing hostility towards the false friends of the workers who spurned or betrayed their own overtures. Furthermore, Stalin’s prediction that capitalism was entering a period of global crisis was confirmed by the mounting evidence of trade imbalance, financial instability and lengthening dole queues. The Australian economy, with its heavy borrowing on the international money market and consequent vulnerability to a downturn in world commodity prices, was already under pressure; attempts to restore profitability by an assault on wages and working conditions caused major industrial disputes in key industries from 1928 onwards. To this extent, the new line announced in Moscow accurately embodied their own experience and aspirations. But how was the offensive against the social democratic and labour parties to be conducted? Strictly speaking, the united front was not abandoned, it was recast as the united front ‘from below’, this signifying the need to detach workers from their treacherous leaders. Yet that formulation hardly indicated the means whereby the communists, who by now were wholly excluded from the organisations they denounced, should effect the necessary internal differentiation. Their perplexity was caused partly by the confusing process whereby the new line was announced during 1928 at the long-delayed Sixth Congresss of the International, where Bukharin (the leader of the right) was still president and tried to play down the change. Within the hall of the Congress his statements were applauded; in the corridors murmurs of his errors presaged Bukharin’s subsequent removal and the replacement of all remaining officials who failed to give complete support to Stalin. The Sixth Congress, moreover, introduced a far more rigid regimen, one which formalised a ‘strict party discipline and precise execution of the decisions of the Communist International, of its agencies and of its leading committees’.23

The unprecedented degree of submission expected of member parties from the late 1920s was a symptom of Stalin’s personal authority but it was also something more. The apocalyptic urgency of the Third Period demanded a break with past habits and old faces. The whole tone of communist pronouncements of Class Against Class, with their insistence on the inexorable logic of class betrayal beneath the benign surface of social democracy and the corresponding emphasis on unmasking traitors, called for new leaders who would exercise new levels of vigilance and impose new standards of obedience. There would be no communist party of any significance outside the Soviet Union that emerged from the Third Period with its leadership intact. The Anglophone parties of Australia, New Zealand, the United States, Canada and, to a lesser extent Britain, all underwent convulsions in which the old leaders were found guilty and removed for the heresy of national exceptionalism.

Three Australians left for Moscow at the close of the 1927 party conference: Moxon, who accompanied Robson as the representative of the Central Executive, and Jeffery and Ryan, who went as delegates to an RILU congress. When the Political Secretariat of the ECCI (chaired by Bukharin, with the British communists Gallacher and Arnot, and the Germans Brandler and Thalheimer) considered Australia in April 1928, it had three reports before it. That of Robson concentrated on the organisational weakness of the Australian party, which it ascribed to factional conflict within the executive while it studiously refrained from political judgement of the issues in dispute.24 That of Moxon rehearsed the factional history of the party from its foundation through to the recent defeat of the right-wing opportunists. It accused the right of intriguing with Robson as well as of subsequent disruption. The lesson of the past few years, Moxon maintained, was that the Labor Party was no longer a working-class party and that any further support of it by the Australian communist party would be ‘next to criminal’.25 In response, Ryan and Jeffery denied factional opposition and described Moxon’s report as ‘a series of misstatements and distortions actuated by personal antagonism’. They described the vagaries of the Australian party’s implementation of the united front policy in conformity with the policy of the Communist International, explained how Moxon had used proxies to control the recent conference, and reiterated their own programme that would concentrate on building a left-wing movement in the Labor Party in order to expose the reformism of its leadership.26

Notably absent from this sheaf of reports as well as from the ensuing ECCI discussion of them was Kavanagh’s argument that building a communist party should be the first priority and that concentration on the Labor Party (whether to work within it or to oppose it) was a diversion. His failure to put his own position to the Communist International at a time when that organisation was invigilating its constituent bodies more closely than ever, and when the question of future relations with social democracy was coming to dominate its deliberations, was a costly error. For the resolution adopted by ECCI concentrated exclusively on the Labor Party in Moxon’s home territory of Queensland. It took its point of departure from an escape clause in the previous year’s resolution when Australian communists had been instructed to continue their efforts in the Labor Party unless and until a genuine left-wing alternative was possible. That possibility was now deemed to have arisen in Queensland because of the reactionary record of the Labor government there, which had already brought the disaffiliation of key left unions. Three or four communist candidates should therefore stand in the state elections due in early 1929; in some other constituencies there should be left-wing ALP candidates supported by ‘workers’ electoral committees’, and elsewhere the Labor candidates were to be pressed, on pain of a campaign against them, to repudiate the past actions of the government and endorse working-class demands.27

Bert Moxon was a delegate to Moscow in 1928. The executive committee of the Communist International accepted his argument that the workers in Queensland were ready to overthrow the treacherous Labor government in that state. The ‘Queensland Resolution’ is here presented as a dazzling dawn. (Source: ‘Workers’ Weekly’, 14 September 1928)

The ‘Queensland resolution’, as it became known, was a compromise—as much an attempt to force the Labor Party to the left as an attack on it; more a bridge between communists and non-communists workers than an attempt to stand on a clear communist platform. As such it allowed each of the Australian factions to claim it for their own. The Australian executive adopted it unanimously. ‘The Party has for some time been preparing the ground for a break with the Labor Party and its reactionary Queensland Government’, explained the Workers’ Weekly when it published the ‘masterly analysis’ of the Communist International. Ryan, Jeffery and Wright joined with Moxon, Miles and Ross to explain why Queensland was peculiarly suited to communist parliamentary candidatures.28 Arguments arose over the programme of demands that should be put to the Labor candidates, with some suggesting that too moderate a programme would merely confirm the workers in their reformist and parliamentary illusions and others wanting to support the electoral endeavours of the left unions. Those issues were taken back to the Communist International by Higgins (who arrived in Moscow in August 1928 as the Australian delegate to the Sixth Congress), which in turn warned against either too hard or too soft a set of demands, neglect of the left unions or subordination of the party to their campaign.29

In short, the implications of the Queensland resolution for the tactics and status of the Australian communist party remained far more ambiguous than the established interpetation of Australian subordination allows. Apparently it was a set of binding instructions handed down from on high. In fact it originated in response to rival claims of local disputants, each of whom appealed for Moscow’s support; its authors attempted to find a via media between the appellants and, even when pressed, refrained from clarification of the issues that separated the Australian factions. Far from exercising a binding control on Australian communists, the Communist International was still criticised for its neglect. In October 1928 the Australian secretary Tom Wright complained that ‘there has been no effective contact with the Communist International’; correspondence was left unanswered, no one in Moscow was responsible for attending to Australian requests, and after Robson’s all too brief visit ten months earlier, the need for a Comintern representative in Australia was pressing. The Australians believed they suffered from their inclusion in the Anglo–American Bureau of the Comintern—for much as Australian imperialists believed Whitehall took Australia’s attachment too much for granted, so Australian communists felt the CPGB patronised the CPA—and thought that they would be better located in the Eastern Secretariat along with China and Japan.30 Perhaps they would have, but the primary reason for their inability to get clear advice during 1928 was the political paralysis of the Communist International itself. That the Australians took so long to grasp that fact only underlines their isolation.

Higgins’s mission to Moscow illustrates these recondite patterns. He went as a member of the minority faction on the Australian executive, which still defended the united front, through the intervention of his British friends Dutt and Pollitt, who spearheaded the shift to Class Against Class in the CPGB. Assisted by these influential figures in the Anglo–American Bureau, he endeavoured (unsuccessfully) to have the CPA transferred to the Eastern Secretariat.31 He arrived in Moscow at the very end of the Sixth Congress, too late to witness the bizarre atmosphere in which Bukharin’s grudging endorsement of the Third Period was adopted unanimously and then set aside. His own report on the Congress caught the essential components of the new line—the deepening contradictions of capitalism and imperialism, the absorption of social democracy into the capitalist state, the need for an intensified struggle, a united front from below—without any indication how these propositions bore on arguments within the Australian party. Apart from pressing the Comintern to clarify the basis of the electoral programme suggested in the Queensland resolution, Higgins explained why the Australian party could not accept other suggestions the Comintern had made: it could not continue to fetter the Minority Movement for the convenience of the New South Wales Labor Council and hence the RILU, since the trade unions were in urgent need of a militant lead; it could not instruct the Australian office of the Pan-Pacific Trade Union to repudiate the White Australia policy since that would threaten its support from the ACTU. For good measure, Higgins asked the Comintern to explain exactly what was meant by its proposed slogan of ‘Australian independence’.32 Yet again the Comintern assured the Australian party that there was no essential difference between its own advice and the local concerns. Yet again they reassured the Australians of greater support and more regular liaison. Higgins did at least take back £1000, the first injection of funds since the British government had prevented the transmission of drafts through London and sorely needed for the new tasks the Australian party had assumed.33

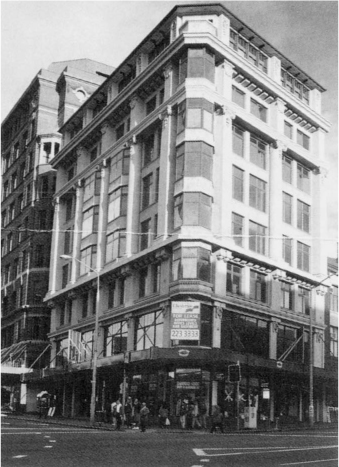

The Communist Party of Australia was conceived in Station House, on the corner of George Street and Rawson Place, close to Central Railway Station in Sydney. Peter Simonoff opened an office there in 1920 as he worked with Earsman, Jollie Smith and Garden to plan the foundation conference. After its foundation, the party leased rooms over the road in Rawson Chambers. Once occupied by trade unions, the refurbished Station House is now leased to business tenants. (Source: Ann Turner)

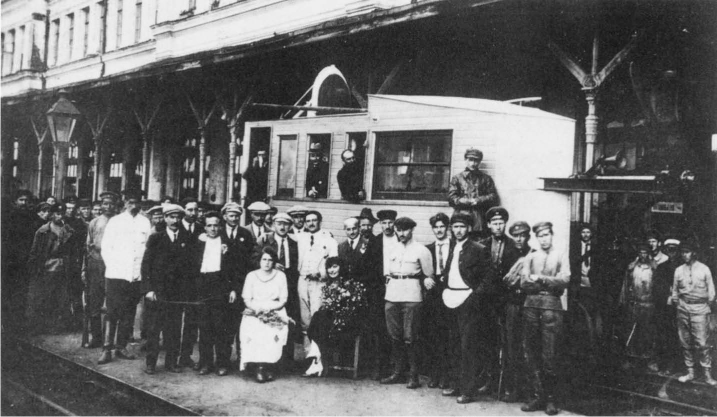

The propellor-driven locomotive that left the rails on 24 July 1921 when Tom Sergeyeff was host to Australian delegates to the Congress of the Communist International. The fortuitous death of Paul Freeman left Bill Earsman to press the claims of the Sussex Street party to a successful conclusion. (Source: Noel Butlin Archives Centre, ANU K4136)

An early gathering of Sydney communists at Balmoral, on Sydney’s North Shore. The variety of the picnickers, young and old, male and female, is striking, and the men’s dress varies from winged collars and bow ties to bathing suits. Norm Jeffery, who kept this photo, appears in a striped costume in the back row. (Source: CPA collection, Mitchell Library Pic Acc 6604)

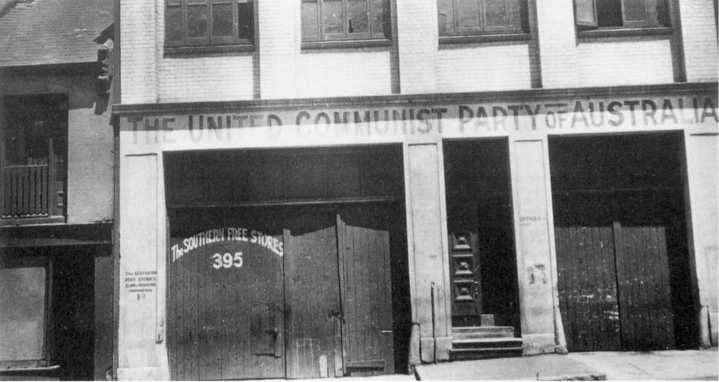

At the end of 1921 Bill Earsman’s party acquired a hall in Sussex Street, after which it became known. The sign ‘The United Communist Party of Australia’ was painted after a conference in February 1922 proclaimed that title. For a decade this was the base of Australian communism; the upstairs hall served as an organisational headquarters, the party’s Saturday dance was held there, and on many nights homeless workers bunked down on its floors. (Source: CPA collection, Mitchell Library Pic Acc 6604)

This studio portrait of John Smith Garden was taken in the 1930s, and shows a more carefully groomed Jock than communists and others of his Trades Hall Reds knew during the preceding decade. A born fixer, he was not without principles. (Source: National Library of Australia, NL 21453)

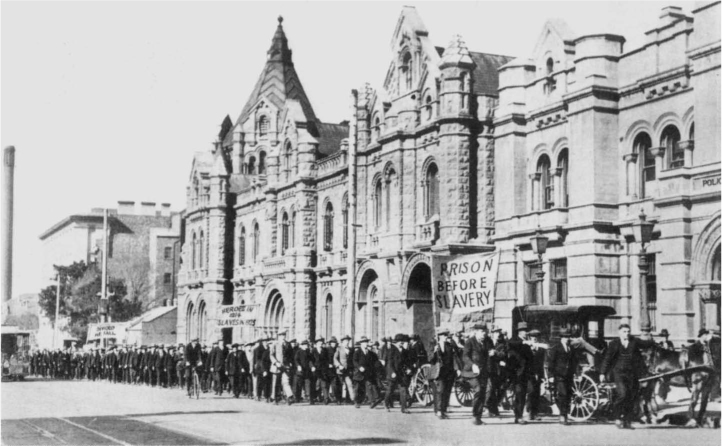

British seamen, prosecuted for participating in the international strike of 1925, march to the magistrates’ court in Melbourne; their counterparts in Sydney sheltered in the Communist Hall. Australian maritime workers bade farewell to one seaman who was deported with the song, ‘Hallelujah! I’m a bum’. (Source: Geoff McDonald collection, Noel Butlin Archives Centre, ANU K3215)

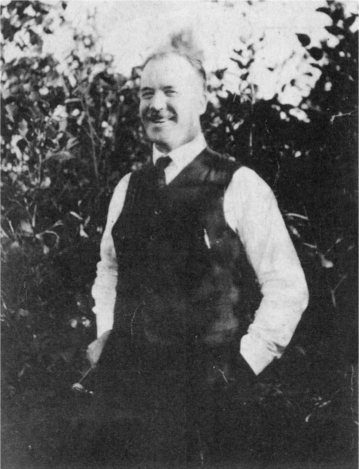

Jack Kavanagh in 1920. Five years later he stepped onto Australian soil and filled the gap left by the departure of the party’s founders. (Source: Jack Kavanagh collection, Noel Butlin Archives Centre, ANU Z400, Box 1)

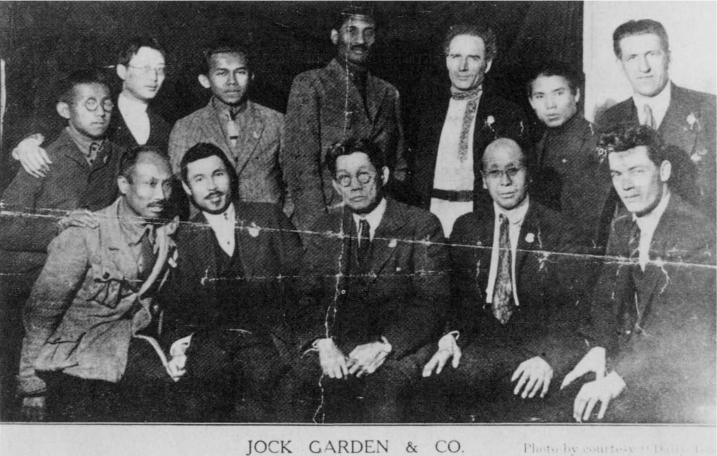

At the Fourth Congress of the Communist International in Moscow during 1922 the Australian delegates were photographed with a group of Asian comrades. Bill Earsman stands third from the right with Jock Garden on the far right of the same row and Tom Payne seated in front of him. The photograph was published by the Nationalists during the 1925 federal election to embarrass the Labor Party. The ‘Labor Daily’ cropped Garden and Payne, and disguised Earsman with a moustache, to accuse the Nationalists of forging the genuine photo. Ever the opportunist, Jock Garden let the chicanery go unchallenged. (Source: F.J. Riley collection, National Library of Australia)

May Day in Lithgow, 1927. The workers at Hoskins steelworks march through the town. (Source: Jack Blake)

May Day in Lithgow, late 1920s. Joy Barrington is up on the stump; Jack Blake stands behind her, his head visible above the hat of a female onlooker. The audience in the park is sparse, the masculine ranks of the unionists who marched replaced by an informal circle of men, women and children. (Source: Jack Blake)

In early 1928 Norm Jeffery and Jack Ryan attended a congress of the Red International of Labor Unions in Moscow. Jeffery also participated in a meeting of communist mining representatives. He appears fifth from the right in the back row; Arthur Horner, the redoubtable leader of the South Wales miners, is third from the right in the front row. (Source: CPA collection, Mitchell Library, Pic Acc 6604)

A group of union officials and communist pickets arrested in Sydney during the timberworkers’ strike of 1929. Left to right: Jock Garden, J. Culbert, Mick Ryan, E.W. Paton, Jack Kavanagh and W. Terry. Though the strike was faltering by this time, the men regard the camera undaunted. Kavanagh’s reputation as a dapper dresser is evident. (Source: F.J. Riley collection, National Library of Australia, PL 667/2)

In 1929 a representative of the Red International of Labor Unions came to Australia to guide the work of the Pan-Pacific Trade Union secretariat. His name was G. Sydor Stöler, but Edna Ryan nicknamed him by his mission as ‘Pan’. He appears here on the left of a group. On the right is Esmonde Higgins; his suit betrays the social origins of which he was so conscious. The woman in the middle is Edna Ryan. (Source: Esmonde Higgins papers, Mitchell Library, Pic Acc 1303/8)

Harry Wicks in the 1950s. The Communist International sent him to Australia in 1930 and, as Herbert Moore, he supervised the reconstruction of the Australian party. (Source: J.N. Rawling collection, Noel Butlin Archives Centre, ANU N57/2295)

In 1931 J.B. Miles moved down from Brisbane to become secretary of the Australian party. With Lance Sharkey, he exercised close control over its activities for the next two decades. (Source: ‘Communist Review’, September 1938)

Beneath the surface of this benign neglect, the Australians jockeyed for advantage. In a rare reference to the projection of local differences into the forums of the Communist International, Esmonde Higgins noted that ‘Mox’ had ‘spoiled things in Moscow’. During his visit to the Soviet Union a few months earlier Moxon had promoted himself, on the basis of his success in Queensland, as the Australian comrade best able to make a clear break with the outmoded tactic of the united front. More than this, he damned the ‘right-wing oppositionists’ collectively and individually in a detailed analysis of the factional composition of the Australian executive that found its way into the Comintern’s records. Higgins did not pursue such vendettas (on the contrary, he supported the election of Kavanagh as a candidate member of the ECCI) but he too used his time in Moscow to cultivate ‘friends at court’. In clear reference to these activities, the ECCI warned the Australian party: ‘care should be taken that questions under discussion must not become the basis for factions and groupings inside the Party’.34 By that time, in the lead-up to the party conference at the end of 1928, factional conflict was endemic. It split the Melbourne branch. Joe Shelley wrote from Sydney at the end of October to his old friend Jack Maruschak, then in Moscow, to report he had been replaced as Melbourne organiser because of an adverse report from ‘that maniac Moxon’—Maruschak prudently forwarded the letter to the secretary of the ECCI.35 It bedevilled relations between Sydney and Brisbane. Moxon was intriguing in Queensland with J. B. Miles, the secretary of the Brisbane group, and ordered back to Sydney; articles submitted by Miles to the Workers’ Weekly were rejected.36

The conference that assembled in Sydney in December 1928 was the largest ever, though party membership showed no improvement. Sydney had declined from 120 nominal members to 80; Brisbane was up from 14 to 44, though many were unfinancial; both Townsville and Cairns reported a high turnover, and most of the smaller north Queensland groups were defunct. Melbourne, similarly, claimed 48 members but only 15 were up to date with dues; Lithgow had fallen to 12 members and lost its Italian section with the closure of the steelworks, and Perth had 14 book members of whom just four were active. There were new groups in the coalmining towns of Bulli and Cessnock. Lithgow had established an outpost at the nearby cement works, while Broken Hill appeared on the records for the first time. Altogether perhaps 300 individuals professed allegiance to the CPA.

Criticism and self-criticism were the order of the day. In his opening address Kavanagh emphasised that the new tasks for party members during the capitalist offensive would call for a level of discipline, training and revolutionary understanding hitherto unattained. The organiser’s report observed the weakness of industrial activity: there was still no effective Minority Movement in Sydney, because the New South Wales Labor Council was still regarded as the arm of the RILU, and in the whole of Australia there were just three communist factory groups. The Lithgow delegates complained particularly of the executive’s lack of support for the Miners’ Minority Movement, which remained the most productive site of communist industrial activity. Several other delegates criticised the failure to organise the growing numbers of the unemployed, and Lithgow members again complained that the executive had refused to assist a recent hunger march of unemployed miners to Sydney. The secretary also acknowledged the neglect of work among European immigrants, and Hetty Ross as women’s organiser lamented the common indifference to the work of the Militant Women’s Groups. The party press came in for trenchant comment: it was abstruse, poorly laid out and too far removed from local activity. That it maintained a circulation of nearly 5000 required constant campaigns and absorbed the energies of its sellers.37

All in all, the picture presented by executive and local members alike was grim. Hector Ross professed himself ‘rather surprised at the mildness of the criticism of the executive’ and observed: ‘We are not a bunch of supermen, we are only a handful of overworked slaves.’ Indeed they were, and the group secretaries presented their own accounts of backward members, contrary members and willing members demoralised by overwork. The Cairns group wanted to ditch its president, who was a professional gambler, but his proposed replacement was too busy in his union. The Brisbane group struggled to maintain viability with at least half its members unemployed. The nomadic habits of the Townsville members made trade union work impractical and left the group in the hands of ‘armchair philosophers’. Melbourne comrades were at each others’ throats and suffered from what its leader described as a ‘very lacka dazical manner’.38 Yet this ramshackle organisation was proposing nothing less than a systematic assault on the leadership of the Labor Party and the unions.

The resolution on the Labor Party was a compromise, put forward with the unanimous support of the executive as a basis for discussion. It proceeded from the postulates of the Third Period: a severe capitalist offensive, the ALP increasingly aligned with capitalism, the Communist Party therefore assuming leadership of the working class. Even so, it tempered fideism with realism. The workers were coming to see the traitorous role of the Labor Party but were not yet willing to accept the full programme of the Communist Party. Accordingly, they should be presented with a programme of left-wing demands. ‘Wherever possible, as in the Queensland State elections, we will put up independent communist candidates or support left-wing workers candidates who support our programme of action.’ Where the weakness of the party made this impossible, the party would promote its programme and endeavour to compel Labor candidates to express agreement with it. Finally, while the CPA would no longer seek affiliation to the ALP, it would continue to fight for the right of trade unions to send communist delegates to ALP conferences.39 The equivocal nature of this resolution, at once condeming Labor and still seeking to influence it, asserting communist leadership while recognising most were still not ready to accept it, allowing that the Queensland resolution might apply beyond Queensland but stopping short of saying so, was plain to the delegates. No one mustered great enthusiasm for the resolution, no one opposed it. There was muted argument over how it should be applied and whether it should have been implemented during the federal elections in the previous month when, for the first time, the wider applicability of the Queensland resolution had been at issue and the executive had belatedly formulated a programme of demands to put to Labor candidates as a condition of support.

The party’s own elections gave the clearest indication of the changing disposition of factional alignments. Kavanagh, Wright, Higgins, Jeffery, Hector Ross and Ryan headed the ballot for the executive, followed by Sharkey, Alf Baker, Barras and finally Moxon.40 Kavanagh and his former critic Higgins had buried their differences, which allowed the re-election of Higgins’s close associate Ryan as well as Jeffery, and pushed Moxon into last place. With Miles ineligible for election (at that time members of the executive had to be resident in Sydney), Moxon’s only ally on the new executive was Lance Sharkey, who had previously been aligned with the faction that resisted Class Against Class but presented himself at the 1928 conference as its ardent advocate. Sharkey was easily underestimated, a man of limited education who lacked the flair and confidence of other leading comrades and seemed to attach himself to stronger personalities—first Kavanagh, now Moxon—but you underestimated him at your peril.41

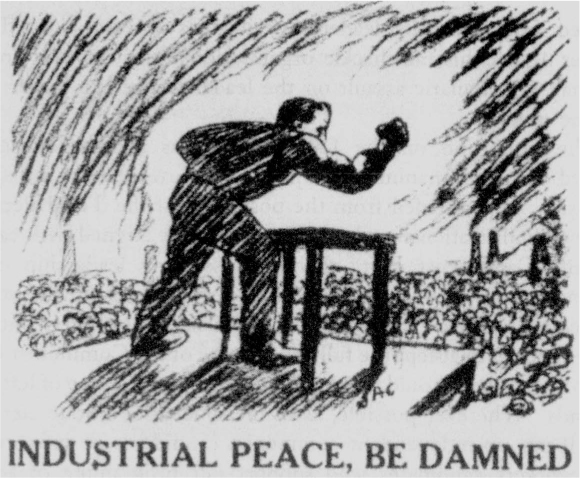

The Communist Party campaigned strongly against the Industrial Peace Conference sponsored by the Commonwealth government in 1928 at the suggestion of the employers, and a crowd singing ‘The Red Flag’ invaded the Sydney session. The image of a muscular militant haranguing an assembled throng before smoking chimneys envisages Lenin’s model of the vanguard party. (Source: ‘Workers’ Weekly’, 30 November 1928)

The other major issue before the party at its 1928 conference was the trade union question. Here too the executive formulated a resolution in the terms of the Third Period. The Australian working class had long basked in illusions of the unique character of its capitalist experience: the isolation from international events, the keen demand for labour, comparatively high living standards and extensive reliance on industrial arbitration all encouraged workers in the belief ‘that Australia was the ‘‘social paradise’’, a country to which the laws of the class struggle did not apply, and which would glide peacefully and without any social upheavals into Socialism’. Now, with the looming economic crisis, a general capitalist offensive was under way. Rationalisation, unemployment and anti-trade union measures were destroying the old illusions, while at the same time the government was drawing the unions into the coils of its Industrial Peace Conference. With the right-wing union leaders committed to class collaboration and the ACTU still weak and vacillating, the task of leadership would fall to the the revolutionary left wing under the leadership of the Communist Party. At this point the party executive again baulked at the implications of its own analysis. Despite or perhaps because of its own weak presence in the unions, the Communist Party remained committed to activity within them; for all its denunciation of the trade union bureaucracy, it still hoped to influence the unions through their officials and the peak industrial bodies, the state trades and labor councils and the ACTU.42 The explanation was simple. The continued affiliation of the New South Wales Labor Council to the RILU was too important to risk by the application of Class Against Class to the industrial field. Except in the case of the miners, whose union was not affiliated to the Labor Council, the Minority Movement therefore remained a lifeless gesture, subordinated to the legacy of the united front.

Almost immediately this vestige of the united front began to break up under the very pressures identified in the communist analysis of the Third Period. As Australia’s economic difficulties mounted, the government and employers launched a major offensive on wages and working conditions. The offensive was at once industrial and political, involving legislators, judges and police as well employers, and the conservative federal government opened it with changes to the procedures and composition of the arbitration court as well as the creation of sweeping new penal powers to enforce court awards. It is difficult to exaggerate the significance of these changes. From the turn of the century, the Australian labour movement had used industrial arbitration as a means of gaining recognition and improvement. Through the associated procedures of wage determination, arbitration served both as a device for the maintenance of living standards and a tangible expression of the belief that the state could reconcile the claims of capital and labour. All this was now placed at risk by the conservative Nationalist government, and with it the attachment of the Australian labour movement to the arbitration system. But this was not the only consequence of the assault on existing industrial awards. Since few unions were capable of resistance in a period of mounting unemployment, and those that did resist were forced to capitulate, the communists assumed an increasingly prominent, oppositional position. The bitter industrial battles fought in 1928, 1929 and 1930 were therefore formative for a new generation of Australian communists. The defeats suffered by the strikers, the failure of the unions to protect them and the conclusions drawn from these events completed the Australian party’s turn to the full rigours of Class Against Class.

There were three principal theatres of conflict, each of them involving a key industry in which large bodies of workers were starved into submission: first, the maritime industry where the dispute lasted from September 1928 to mid-1929 and crippled the Waterside Workers’ Federation; then the timber industry where workers held out from January 1929 to June in Melbourne and October in Sydney; and finally, the coal industry where the miners on the northern New South Wales field were locked out from March 1929 to the middle of 1930.

The ports were the first battleground. Here the waterside workers refused to accept a new award, were fined and then replaced by strikebreakers, who in turn received official preference under the government’s system of licensing workers in the industry. Faced with these sanctions, both the Federation and the ACTU surrendered, leaving aggrieved unionists in some ports to maintain their forlorn cause on picket lines marked by violence, intimidation and victimisation. The Communist Party, which had almost no presence in the waterside workforce or the union at the time, apart from at some north Queensland ports, played no part in these decisions, though the government gave the party prominence when it prosecuted two leading members for publishing a leaflet, ‘Don’t Work Black Ships’. Its direct involvement was restricted to encouragement of the diehards and condemnation of those who betrayed them.43

The timberworkers’ dispute, on the other hand, brought closer communist involvement. The new award handed down by Justice Lukin in January 1929 was so harsh in its provisions—an increase in hours and reduction in wages—that the ACTU declared it ‘the most vicious attack that has been made by the employers through the Arbitration Court on any section of the workers in Australia’, and then set out to limit the union response. Under the authority of the ACTU, the New South Wales Labor Council directed the strike in Sydney, confined the dispute to workers in the industry, supervised the picket lines, collected and distributed relief. Jack Kavanagh, as the Labor Council organiser, thus played a key role, and the Militant Minority Movement and Militant Women’s Group were both prominent auxiliaries. When Lukin ordered a secret ballot of the striking unionists, it was the Communist Party that arranged the public demonstration in the city where the court’s ballot papers were burned along with an effigy of the judge. Of the ballot papers that survived to be counted, 5316 rejected a return to work against 732 in favour. Even as the strike began to fail in Melbourne, there was no weakening of resolve in Sydney. Jock Garden went down to Yallourn to plead for support from the power workers there with one of his characteristically audacious invitations:

One night out for Yallourn would be more than enough for the employers in Melbourne. One night of darkness in Melbourne and there would be a few more new suits worn in the city. The workers would have a few gold watches too.44

Both he and Kavanagh were arrested, convicted and fined under new state anti-picketing legislation. Kavanagh’s position was unenviable. As an officer of the Labor Council he was complicit in its refusal to seek a general stoppage of the building industry. He could see that the strikers were doomed: their exhaustion, the depletion of their strike fund, the weight of police repression and the inability of his flying pickets to prevent resumption of work at one mill after another made this inevitable. But for as long as the timberworkers were prepared to fight on, he fought with them and he was not the only activist who believed this forlorn resistance gave pause to other employers who contemplated wage cuts. At the same time the weight of the Third Period’s logic allowed for no other explanation of failure other than the treachery of the workers’ leaders. Accordingly Kavanagh made an open attack on Garden for his continued participation in the government’s Industrial Peace Conference, and Garden responded by replacing Kavanagh as Labor Council organiser. Thus were the predictions of Class Against Class brought to fruition.45

The mining dispute, the last, most savage and prolonged of these epic industrial conflicts, completed the Communist Party’s shift to a clear oppositional industrial stance. Strictly this was not a strike but a lockout imposed by the coal owners on the miners of the northern New South Wales field. The employers’ insistence on the need to reduce production costs could scarcely disguise the implications of their own defiance of the arbitration system, and the blatant hypocrisy of a government which had enforced the court’s determinations on the wharfies and timberworkers but allowed the coal owners to escape prosecution only strengthened the communist argument that the principles of arbitration were a sham, the court an instrument of capitalist domination. While the policy of the union executive was to restrict the dispute to the northern field and seek redress by arbitration, negotiation, or even by direct government intervention (which the Labor Party promised the miners during the 1929 federal election campaign), the communists sought to extend the stoppage and bring it to resolution, if necessary by calling out safety workers and allowing pits to flood. The communists were best represented on the northern field, and through their Minority Movement they already possessed an influential network of local lodge officials; in the latter part of 1929 these lodges were turned into local councils of action, which coordinated community resistance in the tight-knit pit townships. The failure of the newly elected federal Labor government to make good its promise to end the lockout only increased the miners’ resentment, and the killing of a unionist by New South Wales police at Rothbury in December 1929 hardened their determination. The Rothbury mine was opened by the state government with non-union labour. The Kurri Kurri pipe band led 10 000 protestors in the small hours of 16 December up to the pit, where they were ambushed by armed police. Forty men were wounded; Norman Brown died of a shot in the stomach.

After Rothbury the northern coalfield was an occupied province on which police detachments conducted a reign of terror. Special laws forbade meetings of more than two persons. Baton charges, violent assault and arbitrary arrest became habitual. If there was no dramatic influx of party membership, the quixotic courage of its representatives made a deep impression as leading communists journeyed repeatedly from Sydney into the Hunter Valley to stand on the platform with local comrades and endure bashings, fines and imprisonment.46

The first national conference of the Minority Movement met in July 1929. Bill Orr reported that the executive of the Miners’ Federation had sabotaged the local councils of action and suspended the pickets on the northern coalfield. In the port towns of Queensland, said Ted Tripp, the reactionary union leaders were expelling militants from the trades and labour councils. As chairman, Kavanagh noted the failure of craft unions to support the timberworkers. Despite all these signs of the bankruptcy of union officialdom, the hundred delegates nevertheless resolved to concentrate the energies of their industrial groups on ‘strengthening the trade unions’. Beyond that the majority of the party executive (though not Kavanagh) were still unprepared to advance, since to do so would have been to endanger the affiliation to the RILU of the peak union body in New South Wales, Garden’s Labor Council, and through Garden, the affiliation of the ACTU to the PPTU.47 An RILU official had recently travelled to Sydney to insist that this was sacrosanct.48 The PPTU, after all, linked working-class organisations in China and Japan, as well as those in the extensive East Asian empires of the European powers to their equivalents in Russia, Australia and the United States: it was the most tangible expression of revolutionary internationalism. For all its denunciation of yellow unions and treacherous union leaders, the Communist International therefore made it quite clear to the Australians that these international alliances were more valuable than the tiny Communist Party of Australia. Even the organisation of a national Minority Movement conference had been opposed by the RILU.49 At this point, then, Moscow remained an obstacle to the very changes it urged the CPA to adopt.

In this cartoon produced during the Queensland state election, a worker conveys the Nationalist Party and Labor Party leaders to oblivion. The two politicians are indistinguishable; the avenging worker is a grim and ragged Frankenstein. (Source: ‘Workers’ Weekly’, 3 May 1929)

No one could have predicted the remarkable chain of events that followed. The ruling Australian conservatives, seeking to profit from the turmoil of the strikes and lockouts, changed an industrial offensive into a political controversy, one that soon passed out of their control and turned them out of office. The two main culprits, Prime Minister Bruce and Attorney-General Latham, were brought down by the very spectre of economic misery they had exploited so skilfully before. Having sought and failed to secure additional powers of arbitration to break the strikes, they determined to abandon the jurisdiction, except for the maritime industry, and leave the country’s employers a free hand to break the resistance of their workers. They were brought undone by Billy Hughes, the Labor rat and scourge of the communists, who could not resist the opportunity to avenge himself on the prime minister who had supplanted him six years earlier. In September 1929 he persuaded a small group of fellow malcontents to cross the floor and defeat the legislation. The Nationalists immediately called a snap election in which Labor came forward with new confidence as the defender of arbitration and the saviour of the besieged unions. Here were the very circumstances the Communist International had identified as the Third Period of revolutionary class struggle, the moment at which capitalism fell back on reformists to solve its crisis and communists could at last expose their treachery.

There were only five weeks to polling day and the communist executive’s initial decision that it had neither the time nor the resources to stand candidates is readily intelligible. The recent state election in Queensland, in May 1929, had hardly vindicated the exaggerated claims of the comrades there that the workers were ripe for a revolutionary lead. Even though Miles and Moxon worked as full-time organisers for months and drew on every available assistance, the two communist candidates (Miles in Brisbane, Tripp in Mundingburra) and three left-wing candidates (Fred Paterson was one) attracted just 3194 votes between them as the conservatives swept Labor from office. This did not abash the champions of the Queensland resolution. Miles greeted the defeat of the Labor government as a salutary exposure of reformism, and pronounced the party’s poll ‘satisfactory’. Moxon interpreted the failure of the three left-wing candidates as ‘proof in the future that the workers who will follow a revolutionary policy WILL follow the Revolutionary Party—the Communist Party’. In August he called for the application of the ‘new line’ to every state and to federal politics.50 Most party members, however, recognised the result as a decisive rebuff to their optimistic expectations and the exultation of some Queensland comrades at the defeat of Labor did not improve their popularity.

Moreover, the Queensland election had exhausted the party’s resources. Miles and Moxon were both laid off at the declaration of the poll, and Joe Shelley, sent as replacement organiser to north Queensland, was languishing in Townsville prison as the result of a costly free-speech fight. Party branches in Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth were wracked by dissension, suspension and expulsion. Ted Tripp was due to depart for training at the Lenin School after the Queensland election, but when he arrived in Sydney to receive the money Moscow had sent for his passage, it emerged the executive had long since spent it and in desperation Tom Wright borrowed £65 from Jock Garden.51 Publication of the party’s monthly theoretical magazine had lasped at the end of 1928. There was not even enough money to pay the editor of the Workers’ Weekly, and its future was in any case imperilled by an expensive pending libel action. The party, in short, had taxed its members’ energies to breaking point. The executive therefore decided that the first priority of the Communist Party should be to defeat the conservatives. The Labor Party was weak and unreliable; its leaders were running away from the class struggle; its candidates should be pressed to support a left-wing programme; but under the circumstances there was no alternative but to urge a vote for Labor.52

The decision was immediately challenged by Moxon, who had been brought back to Sydney, and Miles, with whom he remained in regular correspondence. Sharkey joined them in an open challenge, and on 18 September the two dissident members of the executive telegrammed their denunciation of the Australian party’s ‘right deviation’ to the Executive Committee of the Communist International.53 This was an unprecedented move. In the past, Australian communists had privately canvassed support from sympathetic members of the Comintern, but in violating party rules with an open appeal from a majority decision, the dissidents broke new ground. Even then, the Comintern response drew heavily on advice from the Queenslander Ted Tripp, who had recently arrived in Moscow and fully shared Moxon and Sharkey’s zeal for the Third Period.54 The ECCI instructed the Australian executive that support for the Labor Party would violate the decisions of the Sixth Congress; the CPA must run its own candidates and, in the cryptic phraseology of its telegrammed response, ‘MUST COME OUT OWN PLATFORM EXPOSE ARBITRATION AND INDUSTRIAL PEACE COMMON TREACHEROUS ROLE OF BOURGEOIS LABOR PARTY AND REACTIONARY TRADE UNION BUREAUCRACY STOP’. The message reached the Australian executive on 26 September, just sixteen days before election day. It briefly indicated, again by telegram, that there was no time to stand candidates. The ECCI reiterated its earlier instructions, also by telegram. On 8 October Moxon and Sharkey cabled Moscow that their proposal to implement the Comintern instructions had received no support, and a further flurry of telegrams followed.55 By now the ECCI had despatched a lengthy Open Letter for circulation to all Australian members and a special envoy who was to guide the Australian party. The Open Letter would not arrive until the very eve of the annual party conference at the end of the year, but a final telegram, sent on 18 October, put the defiant Australian executive on notice:

PARTYS DUTY AS SOLE PARTY WORKING CLASS CONDUCT INDEPENDENT CLASS POSITION OPPOSITION LABOR PARTY TRADE UNION BUREAUCRACY STOP FIRST CONDITION SUCCESSFUL CONDUCT THIS POLICY RUTHLESSLY COMBATING RIGHT WING DEVIATIONS OWN RANKS BY INTRODUCING STRONGER WIDE SELF CRITICISM STOP … STRAIGHTEN PARTY LINE ACCORDANCE DECISIONS SIXTH CONGRESS TENTH PLENUM AND STRENGTHEN PARTY LEADERSHIP.56

While it was too late to obey the first instruction, the further injunctions could not be ignored. On 25 October, just a week after Labor won the election, the Workers’ Weekly opened a ‘free discussion of the problems of the party’. It continued for two months and was the last discussion of its kind in the party press for several decades. Among the questions Higgins, as editor, posed at the outset were ‘is there a Right danger in the Party?’, and three weeks later he reminded members that it was only one of a number of urgent questions—to no avail, since it was the only question members wished to discuss.57 Their overwhelming response was in the affirmative, and the formulation of the question probably ensured that it would be, for no one wanted to be a champion of the right. Over the course of the discussion the logic of the Third Period came to prevail as party members outbid each other in left virtue. They did so, it should be noted, of their own volition. While publication of the ECCI Open Letter on 6 December informed them where their duty lay, the pattern of conformity was already well established. It is possible to suggest reasons for the voluntary compliance with the new line. The Wall Street Crash on 24 October 1929, demonstrating the severity of the international financial crisis, confirmed earlier predictions of a major depression. The inability of the new federal Labor government to end the lockout of the miners or protect many more workers from layoffs added daily to the plausibility of the Third Period diagnosis. But circumstantial explanations such as these fail to capture the underlying tone of the discussion, which was recriminatory, impatient, enclosed in a logic that understood worse to mean better, verging on a chiliasm of despair that saw past failure as the harbinger of future success.